THE WORKS OF TINTO BRASS

L’uomo che guarda

(a.k.a. The Voyeur, 1994)

In the 1980’s Brass spoke with his friend Alberto Moravia about converting his novel,

L’uomo che guarda (The Man Who Watches) into a screenplay.

This was originally scheduled to go before the cameras in 1986 or 1987.

Moravia, an admirer of Brass’s work, was pleased at the prospect,

but the film was delayed and he did not live to see the result.

This is another Brassian sex-film experiment, and despite its darkness,

it’s a significant improvement over the previous few films.

The story is unusual, and its in-the-family jealousy is vaguely reminiscent of

The Key.

In a nutshell: French-lit professor Edoardo “Dodo”

is puzzled by his wife Silvia’s frequent unexplained disappearances,

and by her brief and unannounced reappearances.

He is even more puzzled by his bedridden father’s success with the ladies.

But all that’s nothing compared to his puzzlement at discovering that

Sylvia is sneaking into his father’s bedroom at night.

And when Sylvia’s confession about what she likes about her secret lover

exactly matches his daddy’s secret proclivities, well, he’s just beside himself with confusion.

But that doesn’t stop them from making up after Dodo finally moves out of his daddy’s apartment

into one of his own — directly above daddy’s.

Odd story.

Not a great story.

Not a deep story.

But odd.

It keeps switching back and forth between stylish drama and farcical comedy.

The technique works beautifully.

Each aspect makes the other more believable.

Visually this is perhaps Brass’s most stunning work.

The art direction, the costumes, the locations, the lighting, the compositions,

and, of course, the looks of the actors all combine to create breathtaking images.

I found the novel at the local library but couldn’t read it because my Italian is too lousy.

Finally I found an English translation (The Voyeur, London: Futura, 1989) and read it.

It’s a short little book, marvelously perceptive, brilliantly written.

The movie is neither perceptive nor brilliant.

It is, instead, an exercise in style.

The basic storyline from the novel is in place, more or less,

and the characters as well, but with all the complications extirpated.

Tinto found every conceivable excuse to have the scenes play in various stages of undress,

which was certainly not true of the novel.

The movie, actually, is a travesty of the novel, but not insultingly so.

It is clear that Tinto loved the book dearly, but was not interested in filming it at all faithfully.

The basic narrative would be used as an excuse to go off on tangents.

(The above can also be said of Tinto’s use of the script for Gore Vidal’s Caligula.)

The result is quite good and a lot of fun, but the result is no longer Moravia.

The movie also does some strange things to the book.

In the book we get the story of child-Dodo’s episode with the postage stamps.

In the movie it is presented as an incomprehensible flashback.

In the book, we understand the disquieting relationship between the child-Dodo and his mother.

In the movie this becomes, shall we say, Oedipal.

One scene in the book, where Dodo as a child chances upon his parents making out in the study,

is especially significant.

In the book, Dodo can only see his mother’s head held down firmly upon the desk by his father.

Tinto added one visual detail: the image of the mother’s rump,

for the scene in the book had occurred almost exactly in the child-Tinto’s real life,

and Tinto added the detail to make the scene autobiographical.

Art imitates life imitates art.

It almost seems that Moravia wrote this story only so that Tinto could make a movie out of it.

Overall the movie is rather fun,

and it has a riotously funny surreal scene at a beach that has to be seen to be believed.

There’s also a shot that nearly made me faint

(I’m surprised I didn’t faint),

as Pascasie, played by Raffaella Offidani,

spreads her legs to show him that she’s been mutilated (“infibulated,” she wrongly says).

That’s not a sight I ever wanted to see.

(You won’t see it in the English dub.)

And, like so many mutilated women, she is defensive about the butchery.

Yes, Brass can be brave, but I thought this was a bit too brave.

Anyway, Dodo’s childhood memories are wonderfully haunting.

REHEARSALS:

When I first saw this movie I was surprised at how rehearsed it looked.

In his earlier films Brass obviously aimed for spontaneity.

Beginning with Miranda

his films look more and more rehearsed.

L’uomo che guarda looks rehearsed almost to death.

The reason for the change is probably Brass’s increasing reliance on nonprofessionals.

This new quality has carried over to all his subsequent films.

Yes, I miss the old style, but, I have to admit, the new style works.

And, as they say in theatre, “If it works, it works.”

|

|

| Fausta provokes Dodo’s rage by telling him what she saw last night |

Katarina Vasilissa and Tinto Brass on the set |

|

|

| Silvia pays a surprise visit to Dodo |

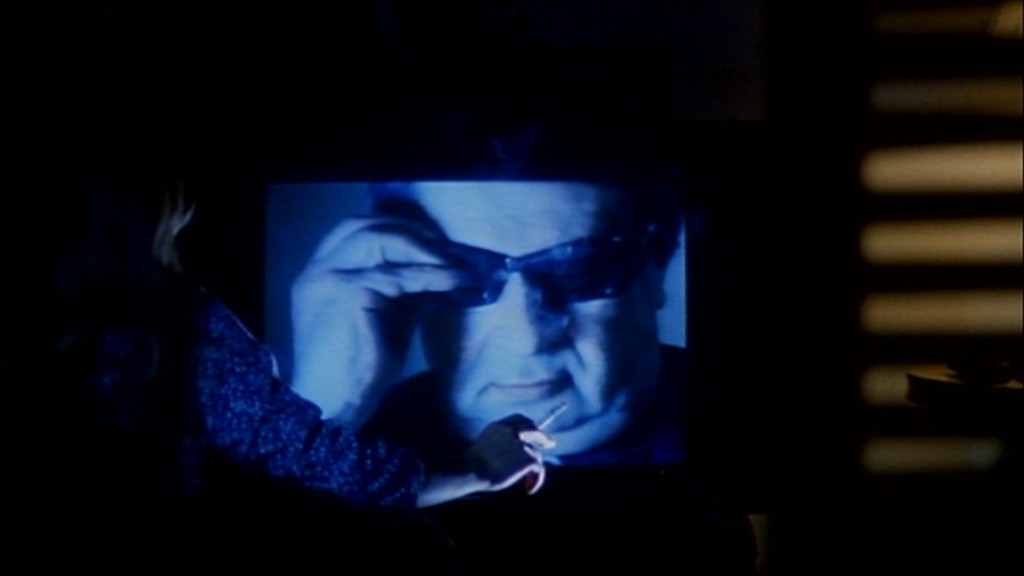

Tinto on the telly

|

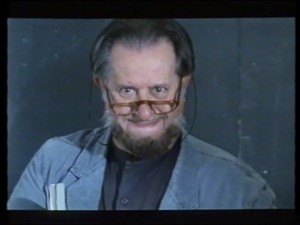

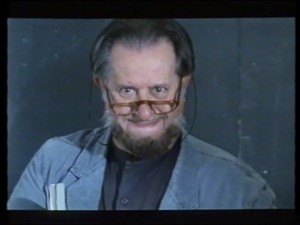

I bet Brass wanted Osiride Pevarello

to play the voyeur at the beach.

Instead he got English dubber

Ted Rusoff,

who looks a little bit like Osiride Pevarello,

to do the honors — in English! — with his his lines dubbed into Italian.

You MUST read what he said about Tinto at

The Film Journal.

|

|

| Giambattista Tiepolo, Woman with a Mandolin, 1755–1760 |

Giambattista Tiepolo, Saint Charles Borromeo, 1769 |

WHERE HAVE WE HEARD THAT BEFORE?

The comic polka from The Key is used yet again,

faintly in the background, during Dodo and Fausta’s first scene together.

And the cheesy jazz piece from Miranda,

which was repeated in Paprika, pops up again here.

CURIOSITIES:

Though Moravia’s original novel is not mentioned in the credits,

it is shown on screen twice:

Dodo peeks through his neighbors’ window and sees them watching what appears to be a porno tape,

but which is actually

the preview

for L’uomo che guarda,

which features Tinto Brass as a voyeur who’s reading Moravia’s L’uomo che guarda.

(How’s that for self-referencing?)

A few moments later, Dodo peeks through a transom window and sees Fausta reading the novel.

There is also some emphasis placed upon Céline’s Nord.

Is that Paolo Lanza at the front of the classroom?

TECHNICAL NOTES:

Most of the film was masked in the camera at 1.66:1 and needs to be projected that way.

Yet several shots were mistakenly masked in the camera at the smaller 1.75:1.

If you don’t understand the difference, study the frame captures below.

WARNING:

Yes, there is an English dub available in PAL-system Region-2 DVD from England, and also now released in the US.

Do not watch it.

The English dub is cut to pieces — and it’s a lousy transfer to boot —

and whoever dubbed Dodo sounded like a dork.

And many of the opening and closing credits in the English version are wrong —

as is the dubbing when

The Key is playing on the cinema screen.

The Italian version is a million times better, and quite a bit longer too.

If you decide to order the US DVD from Cult Epics,

be sure to choose the “Director’s Cut,” not the “Producer’s Cut.”

SO YOU THINK I’M BEING TOO PICKY?

Well... in the sloppy English version:

The assistant editor was credited as editor.

Not too bad, you think, huh? Okay.

The still photographer was credited as director of photography.

The director of photography was credited as still photographer.

Still making a mountain out of a mole hill, am I?

Well, here are some more examples:

The dialogue coach was credited as script writer.

The second assistant director was credited as location assistant.

The camera operator was credited as generator operator.

The focus puller was credited as electrician.

The generator operator was credited as crowd coordinator.

The chauffeurs were credited as the production office.

The recording studio was credited as “scoring.”

The upholsterers were credited as painters.

Well, people say I’m just too picky.

It was at about this time that Variety journalists “Hawk” (Robert F. Hawkins) and David Rooney published a paperback called

Italian Cinema: From the Golden Years to the 1990’s (Variety, Inc., 1995).

A biographical section includes an entry for Tinto Brass (pp. 120–122), which is most disheartening.

This is what happens when a filmmaker issues some films that fail at the boxoffice due to inadequate distribution,

then follows up with studio assignments such as Salon Kitty and Caligula,

and finally is typecast as a T&A impresario.

When that happens, authorities look back on everything from a jaundiced perspective, and this is the result.

It is surprising (or is it?) that even Variety journalists fall into the trap of thinking that directors make only what they want.

How do they fail to realize that, more often than not, producers tell the directors what to make?

It is also surprising (or is it?) that even Variety journalists get basic facts wrong.

The poor grammar, by the way, is from the original.

Witness:

|

One of the most curious figures to gain notoriety in the Italian

film industry in the years that came after the creative boom was

Tinto Brass.

After establishing the beginnings of a promising directing

career with his early features of the 1960’s, however, Brass

gradually gave in to a yen for calculatedly provocative scandal-mongering

and to a facile fascination with hopelessly kitsch,

undergraduate erotica.

The anarchic humour of his 1963 debut, Chi lavora è perduto,

was followed by explorations — some more dedicated than others —

over the next decade, of various genres from Western to cop

thriller to homespun sci-fi to bizarre 1960’s social rebellion tract,

none of which have aged well.

Brass finally forged a reputation that stuck with his 1976 opus,

Salon Kitty, an orgy of goosestepping and unsavory sexual

shenanigans set in a Nazi brothel. The film attempts to muster a

raison d’être similar to that of Cavani’s films by exposing the

ugliness of power. But it remains a highly sensationalist

undertaking primarily concerned with grotesque titillation.

The director’s association with historical sex sprees was

cemented by his disastrous 1980 romp through ancient Rome,

Caligula. Original writer Gore Vidal demanded to have his name

removed from the credits, and Penthouse magazine magnate Bob

Guccione, who produced, attempted to prevent Brass from

completing the picture. But completed it was, ending up as a $15

million serving of ugly gore and lackluster carnality that most of

those involved spent years trying to live down.

Brass, however, responded with gusto to the ongoing call of

the ribald with such films as La chiave (1983_, which re-established

Stefania Sandrelli’s popularity, Miranda (1985) and

Capriccio (1987). The director earned few friends among critics

but found favor at the box-office with long lines of flesh fanciers.

Brass’s films have launched a string of popular female stars,

like Serena Grandi, Francesca Dellera and later, Deborah

Caprioglio and Claudia Koll, respectively in 1991’s Paprika and

Così fan tutte the following year. All of these actresses, however,

have since sworn off disrobing and taken up more mainstream

careers.

Over the years, Brass’s films have become progressively less

narrative-driven and more and more concerned with matters

gynaecological, thumbing their nose at anything approaching

directorial refinement to probe the pleasures of commonplace

schoolboy voyeurism.

|

|

| The Italian Region-2 PAL DVD, which will not play on most US equipment.

The DVD transfer is quite good,

but cropped to 1.75:1,

which is rather tight but it still works,

despite the tops of so many heads being cropped off.

Oddly, the image is off-center,

with a black border appearing only on the left side of the screen. |

VHS

Entire 1.66:1 image transferred through the larger 1.375:1 aperture,

and slightly windowboxed.

You will notice that the camera aperture was overfiled

(which is quite common) and is actually a bit taller,

closer to 1.51:1.

But, of course, since there is no such projection format,

it was never intended to be shown that way. |

DVD

Italian edition from CVC cropped to 1.75:1

(The US edition from Cult Epics is rather less cruel than the CVC edition) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| This is one of the two or three shots masked in the camera at 1.75:1.

No, not matted in the lab.

If it had been matted in the lab, the sheen from her hair at the top right of the image would not curve into the black border. You are probably wondering why, since the images on left and right are both 1.75:1, they look slightly different.

The answer might be rather surprising.

Films begin to shrink as soon as they come out of the lab,

and they continue to shrink until they disintegrate entirely.

Thus it is common practice for the image on the film

to be ever so slightly larger than the image that will be shown on the cinema screen.

This is done simply as a safety precaution.

1.75:1 on unshrunken film is .864" × .494".

The corresponding projector aperture is .825" × .471".

As the film shrinks over the first few months of its life,

the size of the image shrinks to something

very close to the size of the projector aperture.

Eventually it will shrink so much that it won’t be projectable, and new prints from the shrunken negative will have duplicated images toward the frame lines as well as black borders on the sides that will show on screen. Also showing on screen will be images of the negative’ sprocket holes, usually on the right side of the frame.

Because the badly shrunken negative will no longer fit onto a normal printer,

it is transported by sprocket holes along

only one side of film and is thus printed off-center. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Oops. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Lulù and Matteo |

|

|

|

|

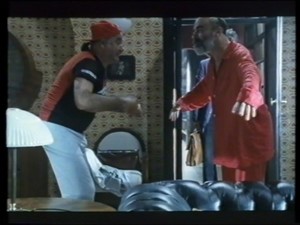

| Theatrical greats Antonio Salines and Franco Branciaroli

having a great time acting silly. |

|

|

|

|

| Emotional turmoil depicted by a deliberately mistimed and undersized shutter.

(This effect creates emotional turmoil in the projectionist, who will panic that the shutter clamp has slipped or that a gear has stripped.)

The effect, of course, bleeds into the part of the frame that is normally masked off. |

|

|

| Dubbing director

Ted

Rusoff as the Porking Attendant. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

DARC Distribuzione Angelo Rizzoli

Cinematografica

Marco Poccioni, Marco Valsania e Angelo

Rizzoli presentano

un film di Tinto Brass

L’uomo che guarda

copyright © 1993 FIN DU BARIL

1138:26:22 Rodeo Drive srl Erre

Cinematografica srl

Soggetto e sceneggiatura di

(original story and screenplay) |

Tinto Brass |

| Liberamente tratta dal romanzo omonimo di (freely adapted from the novel of the same name by) |

Alberto Moravia [uncredited but explicitly referenced] |

| Collaborazione al montaggio (assistant editor) |

Fiorenza Müller |

| Fotografo di scena (still photographer) |

Gianfranco Salis |

| Segretaria di edizione (continuity) |

Carla Cipriani |

| Fotografia (director of photography) |

Massimo di Venanzo |

Scenografia e arredamento

(art direction and set décor) |

Maria Luigia Battani |

| Costumi (costumes) |

Millina Deodato |

Musiche composte e dirette da

(music composed and directed by) |

Riz Ortolani |

| Direttore di produzione (production manager) |

Carmine Parmigiani |

Organizzatore della produzione

(accounts manager) |

Claudio Grassetti |

| Prodotto da (produced by) |

Marco Poccioni e Marco Valsania per Rodeo Drive srl, Erre Cinematografica srl |

Scritto diretto e montato da

(written, directed, and edited by) |

Tinto Brass |

| Aiuto regista (assistant director) |

Claudio Bernabei |

| Dialoghista (dialogue coach) |

Michela Prodan |

| Assistente regia (assistant to the director) |

Sabrina Ascani |

| Operatore di macchina (camera operator) |

Renato Palmieri |

Assistente operatore

(assistant camera operator) |

Pierandrea Pierpaoli |

| Aiuto operatore (assistant camera operator) |

Claudio Palmieri |

| Operatore steady-cam |

Sergio Melaranci |

| Fonico (sound) |

Andrea Petrucci |

| Microfonista (boom operator) |

Aristide Bigliocchi

[uncredited in English version] |

Assistenti al montaggio

(assistants to the editor) |

Emanuela Lucidi, Giovanna Ritter, Flora Elisa Algeri Bricoli, Carlo Simeoni |

| Assistenti scenografia (assistant art directors) |

Carlo de Marino, Aslessandra Martelli |

| Assistente costumi (assistant costumer) |

Cristiana Ricceri |

| Parucchiera (hairdresser) |

Jole Cecchini |

| Truccatore (make-up) |

Dirk Naastepad |

| Sarte (dressmakers) |

Gabriella Morganti, Edda Soliani |

| Amministratori (production accountants) |

Daniela Berardi, Angelo Frezza |

| Ispettore di produzione (unit manager) |

Walter Mancini |

| Segreatri di produzione (production secretaries) |

Francesca Romana Deodato, Patricia Radovic, Marco Spoletini |

| Aiuto segretario (assistant secretary) |

Ferdinando Bossi |

| Cassiera (payroll) |

Cristiana Valle |

| Capo squadra attrezzisti (prop master) |

Roberto Magagnini |

| Attrezzista (props) |

Ubaldo Panunzi

[uncredited in English version] |

| Aiuto attrezzista (prop assistants) |

Massimo Nespoli |

| Capo squadro elettricisti (gaffer) |

Romano Mosconi |

| Elettricisti (best boys) |

Domenico Zenga, Pietro Sottile, Carlo Catini |

| Capo squadro macchinisti (key grip) |

Vittorio Rocchetti |

| Macchinisti (grips) |

Paolo Anzellotti, Marcello Negretti, Massimo Spina |

| Gruppista (generator operator) |

Massimo Malfa |

| Autisti produzione |

Mauro Babini, Atef Abdelwahed |

| Autisti (drivers) |

Giorgio Ricci, Davide Biancifiori,

Stefano Marchetti |

| Ufficio stampa (publicity) |

Intesa & Intesa srl |

| Adetta locations (location manager) |

Ada Locatelli |

Teatri di posa, laboratorio, Mezzi tecnici

(studio, lab, technical equipment) |

Cinecittà [uncredited in English version] |

| Pellicola (raw stock) |

Agfa-Gevaert |

| Tecnico del colore (color technician) |

Stefano Giovannini |

| Sonorizzazione (recording studio) |

Fono Roma Film Recording |

|

Dolby Stereo in teatri scelti |

| Assistente al doppiaggio (assistant dubber) |

Corrado Russo

[uncredited in English version] |

| Fonico del doppiaggio (dubbing recorder) |

Franco Mirra

[uncredited in English version] |

| Mixage (mixer) |

Alberto Doni |

| Effetti sonori (sound effects) |

Cine Audio Effects

[uncredited in English version] |

| Titoli (titles) |

Studio 4 [uncredited in English version] |

| Lampade (lights) |

R.E.C. sas |

| Trasporti (transport) |

Eurocinetransport |

| Assicurazione (insurance) |

Cinesicurtà |

| Edizioni musicali (music publishers) |

B.M.G. Ariola spa |

| Sartoria (wardrobe) |

Gi.Elle |

| Gioielli (jewelry) |

La.Ba [uncredited in English version] |

| Parrucche (wigs) |

Rocchetti & Carboni |

| Tappezzeria (upholstery) |

Artigiana Arredatori e Tappezzieri, Sanchini |

| Arredamento (set décor) |

G.R.P. Arredamenti Cineteatrali, E. Rancati, La Teca dell’Immaginario |

Si ringrazia per la collaborazione

(for their collaboration, we thank) |

Polaroid

Piaggio

Quotidienne

Impec

Garbo

Nouvelle Vague

Marvel

Mishelle

Desmo

Selene

Mediateca del Centro Culturale Francese

Varaschin Rattan spa

Becchetti Angelo Bal

Artemide

Unopiú

Olri Argenti [uncredited in English version]

Intonacopronto srl |

| English version |

Double Vue (N.B.) INC. |

| Directed by |

Thor Bishopric |

| PERSONAGGI E INTERPRETI |

|

| Silvia |

Katarina Vasilissa |

| Edoardo “Dodo” |

Francesco Casale |

| Fausta |

Cristina Garavaglia |

| Pascasie |

Raffaella Offidani |

| Dottore |

Antonio Salines |

| Pascasie’s roommate |

Eleonora de Grassi |

| Madre di Dodò |

Gabri Crea |

| Contessa |

Martine Brochard |

| Alberto |

Franco Branciaroli |

| Suora nella piaggia |

Erika Saffo Savastani |

| ??? |

Paolo Murano |

| Parcheggiatore/Porcheggiatore |

Ted Rusoff |

| Student outside class window |

Maria la Rosa |

| Bambini |

Lulù e Matteo |

| Professore / attore |

Tinto Brass [uncredited] |

|