| Return home |  |

Return to previous page |

Early 1927: Paramount Slashes

the Export Negative, Too

the Export Negative, Too

Per contract, Paramount would prepare the export edition.

We can see that the cuts Channing Pollock ordered for the US edition were made also in the export edition,

and Channing is indeed credited in the export edition.

Publix, which did not have overseas cinemas, took no interest in the export edition,

and so Paramount did not cut the export edition further, but just left it more or less as Channing wanted it.

The result was more than two reels longer than the US edition, a bit above 10,700'.

Paramount sent this negative to Ufa,

which made some prints for export to various countries, including the UK and Australia and New Zealand and surely elsewhere, too.

The distributors in Australia and New Zealand hacked away at the individual prints to abridge them.

As for the British edition, the censors cut it slightly to

10,695'.

Aitam Bar-Sagi pretty much confirms this when he refers us to the

BBFC Classification Record,

which states that Wardour submitted its version for classification on 18 March 1927,

which fits the rest of the data, since it opened on schedule on Monday, 21 March 1927, at the Marble Arch Pavilion.

Now, there are two problems with the BBFC record.

It states that the film was cut, but by how much, or what precisely the cuts were, is a mystery.

It does not give an exact footage or speed.

My best guess is that the robot’s dance was trimmed by two or three seconds.

The film as submitted was “118:13,” which is a few seconds shy of 10,695' if projected at the usual 90'/min. (24fps).

Curiously, Paul Reno’s shortened German version, which would go into release in Germany in August, was 10,633',

spookily close to the British edition.

Ah! I just stumbled upon

this fantastic web page on Metropolis,

which reproduces the original British program.

British critics were agonizingly aware that the film had been mutilated,

and they did not keep that a secret from their readers.

As we see, H.G. Wells was among the VIP’s who attended opening night in London,

and he wrote the most intelligent review of all.

Click on the two images below to enlarge:

I cannot fault dear old Herbert.

His comments are all

I cannot fault dear old Herbert.

His comments are all |

Merriam-Webster: science fiction

fiction dealing principally with the impact of actual or imagined science

on society or individuals or having a scientific factor as an essential orienting component

Literary Terms: Science Fiction

a genre of fiction literature whose content is imaginative, but based in science.

It relies heavily on scientific facts, theories, and principles

as support for its settings, characters, themes, and plot-lines, which is what makes it different from fantasy.

Britannica: science fiction

a form of fiction that deals principally with the impact of actual or imagined science upon society or individuals.

Wikipedia: Science fiction

a genre of speculative fiction, which typically deals

with imaginative and futuristic concepts such as

advanced science and technology, space exploration, time travel, parallel universes, and extraterrestrial life.

Merriam-Webster: allegory

the expression by means of symbolic fictional figures and actions of truths or generalizations about human existence

Literary Terms: Allegory

An allegory (

Britannica: allegory

a symbolic fictional narrative that conveys a meaning not explicitly set forth in the narrative.

Allegory, which encompasses such forms as fable, parable, and apologue,

may have meaning on two or more levels that the reader can understand only through an interpretive process.

Wikipedia: Allegory

As a literary device or artistic form, an allegory is a narrative or visual representation in which a character, place, or event can be interpreted to represent a hidden meaning with moral or political significance. Authors have used allegory throughout history in all forms of art to illustrate or convey complex ideas and concepts in ways that are comprehensible or striking to its viewers, readers, or listeners.

|

That was the bait and switch.

What the prestigious audience received was not science fiction or futuristic at all;

it was political/social/psychological allegory.

More importantly, it was a simplistic joke, a deliberately ridiculous exaggeration,

playfully presented in a pseudo-naïve way.

Herbert responded to it as though it were a failed attempt at futuristic science fiction.

Insofar as that was the false representation, his comments are unimpeachable.

After all, the copy of the movie that Herbert saw contained Channing Pollock’s prologue,

which stated that the movie depicts our future.

The original film, of course, said no such thing and implied no such thing.

To my surprise, Fritz Lang himself said that the story took place in

“the future,” but what future?

The future a month hence?

To me, taking the story at a superficial level, it reads like a fairly mindless allegory of 1926 Germany;

it has nothing to do with any future.

If there had been no such prologue,

I wonder if Herbert’s reaction would have been a mite different.

The movie is not as simplistic as it at first appears.

Once one understands the agitprop, one can see that it is actually quite brilliant.

The movie is a mood piece, a dreamlike allegory of 1926.

Further, as we can see, especially now that most of the missing scenes have been put back in,

the movie is a satire, a joke about gangster capitalism,

done in farcical way, in an intentionally preposterous and ridiculous fashion.

If you take it as a joke, it’s actually pretty darned amusing.

Freder’s shock at finding Maria with his dad,

Der Schmale transforming into the monk,

the workers manically dancing through the factory,

oh come on, that’s really funny stuff.

Would Fritz Lang have agreed with my interpretation?

Probably not.

Regardless, that is how I see the result.

Anyway, I wonder: Why do people say that this movie is science fiction?

Because it opens with pistons and gears?

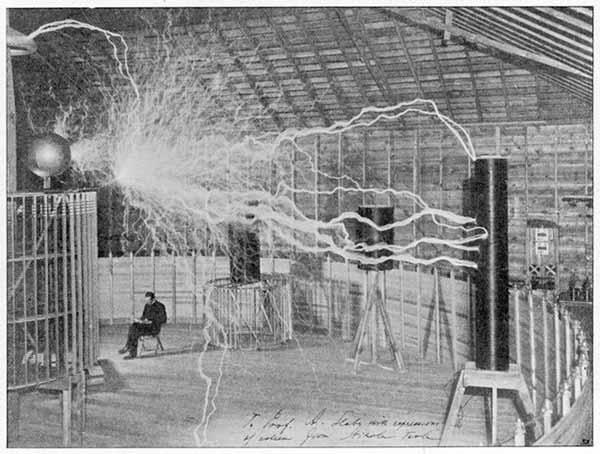

Because we see electrical arcing?

Again, we all watch the same thing, but we see entirely different things.

Others watch Metropolis and see science fiction.

I watch Metropolis and see farce and comedy and allegory and gobs and gobs of mystical hokum

borrowed from here, there, and everywhere.

Here is what I see clearly, screaming at us all, and yet nobody else seems ever to have noticed.

Rotwang (Rosy Cheek, or Red Cheek) and Joh are two aspects of the same entity.

Another way to put it is that each is a symbol of a phase of the evolution of consciousness and of conscience,

with Rosy Cheek being the symbol of the more primitive stage of development and Joh being the symbol of the following stage of development.

Rosy Cheek, the more primitive phase, is soon to be shed (like a snake skin) to allow the modern phase to evolve.

Why is he Red/Rosy?

As you will learn below, it has been suggested that his name is a cryptic reference to International Communism.

I am more inclined to think it might be a cryptic reference to Rosicrucianism.

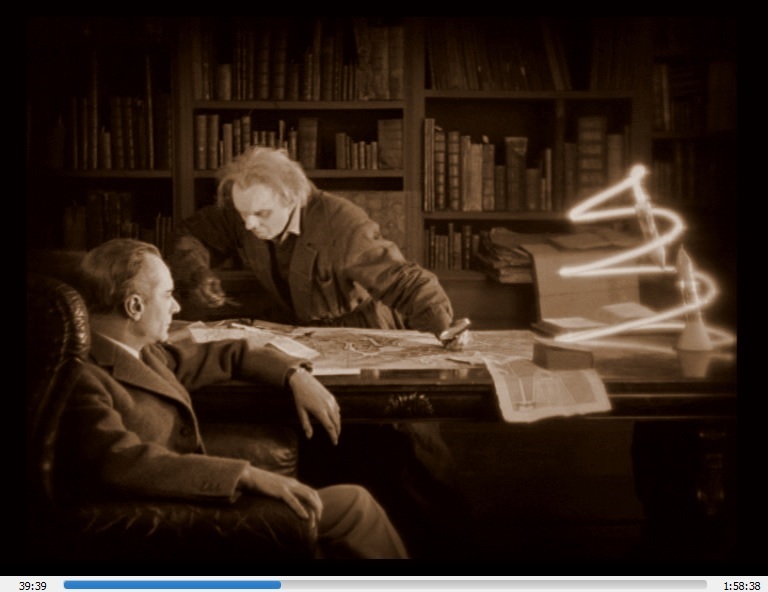

Rosy Cheek is dressed in something resembling a medieval robe, and his dwarf servant is dressed almost as though in a medieval court.

Rosy Cheek performs all sorts of chemical and electrical tinkery-blinkery

that in the real world would accomplish nothing except to raise his utility bill and burn his house down,

but look at his library:

Every book in it is a century old.

That is not a scientist’s library.

That is not a scientist’s study.

He’s some sort of wizard,

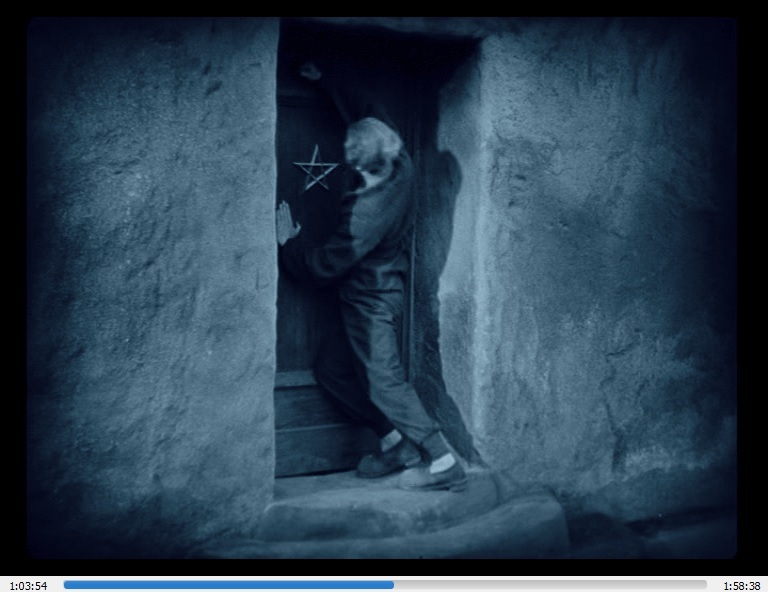

living in an ancient house with a cellar that leads to the ancient catacombs far below ground;

he emerges from the realm of the dead and remains in communion with it.

In the original version of the film, the catacombs are called “the City of the Dead.”

The only non-modern structure in Metropolis,

rising from the ground like an unwanted memory that no one can wipe away.

On the front door is a symbol that is too far away to make out, but that we shall discover soon enough.

“So, Mr. Rosy Cheek, you’re in the market for a house?”

“Yes, but I am particular about what I want.”

“Whatever it is you wish, I’m sure we have it.”

“I want an ancient house with no windows on the walls.

It must be several stories tall and it needs to look decrepit,

but it nonetheless must be sturdy enough for an electrical laboratory where I can build a golem.

It must have a cellar door with a staircase that will take me far below the surface of the earth

and lead me to the forgotten catacombs built one thousand five hundred years ago.”

“We have just the property for you!”

In this story, underground has overlapping meanings: the subconscious, the world of the dead, and the buried (suppressed) past.

Who should Rosy Cheek’s beloved have been other than Hel?

Hel is the goddess of the World of Darkness, the goddess of those who did not die in battle.

The movie Hel was imprisoned in the realm of the dead upon exchanging obsolete Rosy Cheek for his more evolved aspect.

Hel bears some slight familial resemblance to Maria, and that is surely intentional,

as each proves to be an aspect of the other.

A star (a Pythagorean symbol of life, or a Rosicrucian symbol of spirit over matter) is on Rosy Cheek’s front door.

Several critics (for example,

this one) have objected to this scene as antisemitic,

claiming that this is a Star of David. Say what?

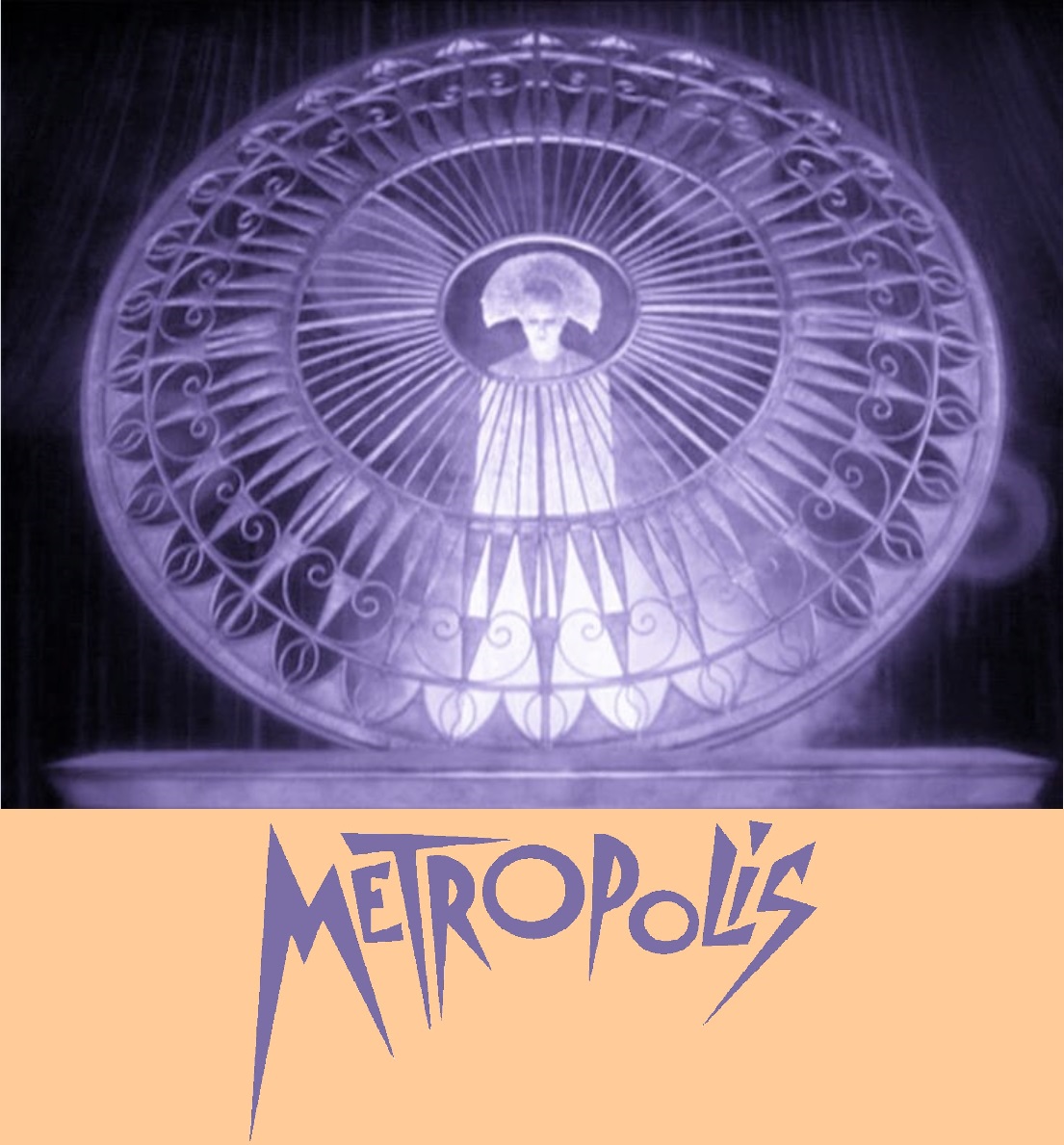

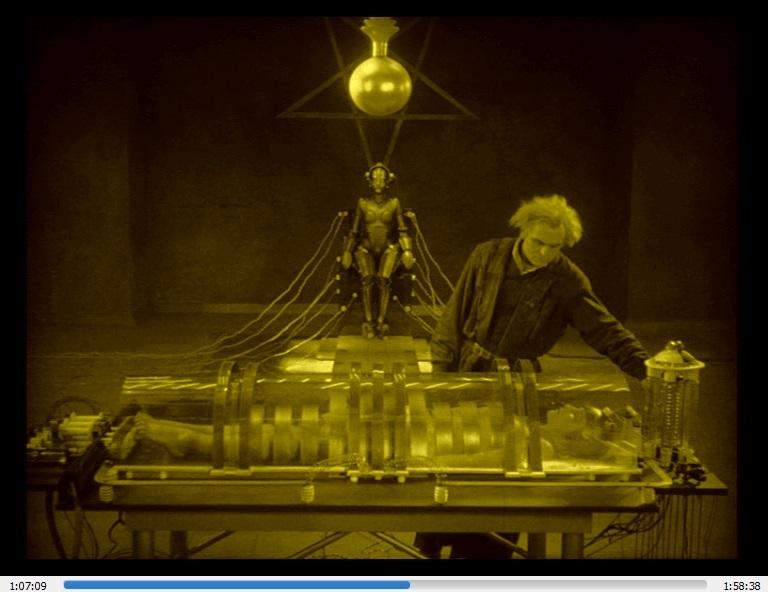

In his lab is the same star, inverted to resemble the symbol of Baphomet.

This is the Rosicrucian symbol of matter over spirit.

It points directly down at the golem, a duplicate (but inverse) of his beloved deceased Hel.

Demon est deus inversus (a demon is an inverted god), according to the Kabbalah.

Rosy Cheek remodels the inverse of Hel into the inverse of Maria, and Maria, of course,

is the Virgin Mary in Christian mythology, an extrapolation of Isis.

Look again at the Baphomet symbol in the lab as Rosy Cheek readies the inversion of the Virgin Mary.

The way the camera is positioned, in the exact center of the Baphomet symbol is some sort of globular anode dangling from the ceiling.

In this camera angle, and only here, it resembles the orb and cross held by Christ Pantocrator.

It’s not exact, but close enough that one cannot help but be reminded of the common iconography, and that is not a coincidence or an accident.

Wait a minute.

I’ve seen that anode before, and so have you:

Thea von Harbou, and later Fritz Lang, added the Norse stuff to the Judæo-Christian stuff

and tossed it all into a stew together with the übernationalist expectation of a new German Messiah

represented by Freder (the name means Peaceful Ruler — Freder Fredersen is The Peaceful Ruler, Son of the Peaceful Ruler).

Freder’s dad is Joh Fredersen, and so I just went to Google and typed in Joh.

I was expecting it to be an abbreviation of

Johannes, and it seems that it is.

Johannes = Ἰωάννης,

which comes from Yehochanan

(יְהוֹחָנָן),

which means Yahweh Has Been Gracious.

Johannes or Johanes or Johann in German is the same as John in English.

It is significant that much of the Metropolis story is derived from the Revelation of St. John, or, in German,

Die Offenbarung Sankt Johannis.

Funny stuff. Really funny stuff.

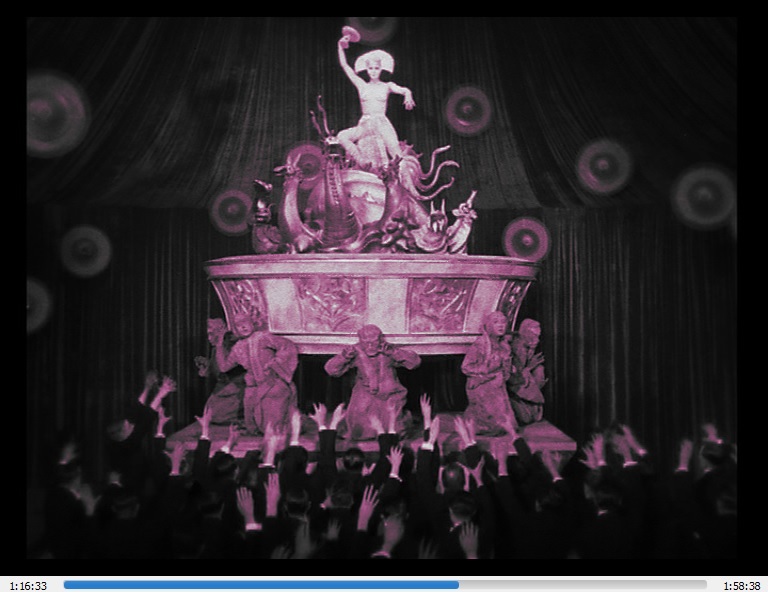

A stage floor shaped like a powder container is balanced

on the shoulders of statues of seven African slaves.

Along the curtains are round ornaments that seem to mean nothing — yet.

They soon parallel the eyes of the congregation.

(More about this below.)

The Seven Deadly Sins relieve the African slaves of their burden.

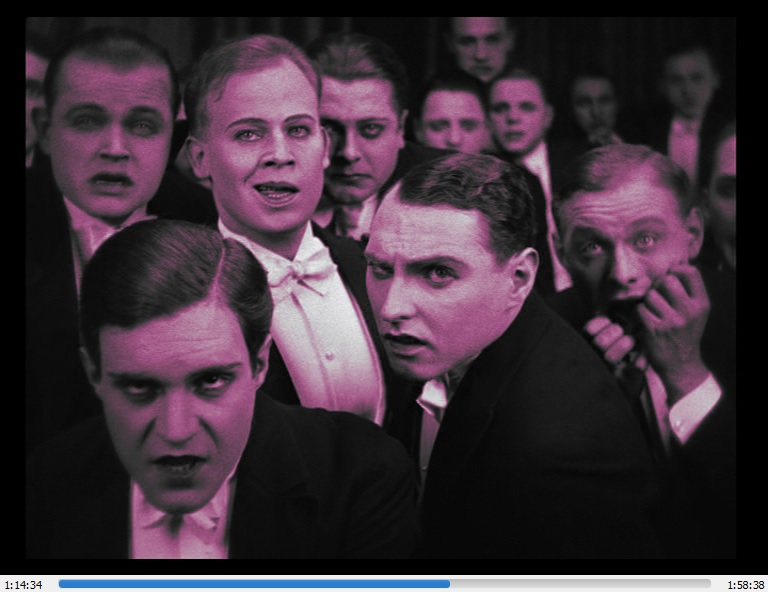

Worshippers.

Devotion.

When the wandering people are led by the Whore of Babylon to attack the Heart,

they unleash a flood that wipes out the entire slave world,

but the Messiah/Peaceful Ruler (son of Hel), together with the Virgin Mary and Josaphat (Yahweh Is Judge),

rescues the children by leading them up from the underworld to the Club of the Sons,

which must have some sort of mystical meaning that is over my head.

I Googled it but found only a rock group.

A really nice touch is that when Maria first sees the flood, she does not witness a torrential river sweeping all away in its path.

Instead, she sees the flood rising through the floor from below.

Again, this is the subconscious.

If you wish to dip your shoes into a bit more of this esoteric babble,

which is really enjoyable esoteric babble, I must admit,

take a look at an unsigned article called

“The Occult Symbolism of Movie ‘Metropolis’ and its Importance in Pop Culture”

in The Vigilant Citizen, 19 October 2010.

It’s loads of fun, some of it is spot-on ,

but some of it it is also rather wacky and misses the mark by a mile.

I get the idea that the anonymous author might not really be serious about uncovering hidden meanings;

rather, I think he is playing a game, trying to misdirect us, convincing us to find evidence of sinister conspiracies where there is really only playful monkey-see , monkey-do .

(Yes, the author is a he, I am certain.)

When the studio bosses and Pollock slashed so much of the story away,

they omitted much of the above meaning, if meaning is the correct word.

Even so, some of the ideas were still visible.

I discover, from Elsaesser’s pamphlet, that a few people caught a little of this.

Most people, though, seem to have been oblivious to everything save the simplistic plot.