The preview above was obviously shown in England, and so, yes, it was likely shown in Australia as well, but blast it all!

It cuts off before we can see the distributor’s credit or any other credits!

Phooey and fiddlesticks!

We need to know who the British distributor was!

Might it have been Wardour Films?

Alas not, because Wardour Films went out of business in the middle of 1938.

Some other company acquired some or all of Wardour’s holdings, but what company?

We learn a little bit.

Wardour Films begat the Associated British Picture Corporation, which, under a Mr.

Arthur Dent, believe it or not,

took control of two cinema circuits in England, namely Union Cinemas and A.B.C. (Associated British Cinemas).

A good guess is that, upon the dissolution of Wardour, Associated British Picture Corporation claimed its holdings.

Yes? Makes sense? Maybe?

IMDb, predictably, is of no help.

Its list of distributors jumps from 1929 to 1984, but a great deal happened in the 54 years in between, ya know.

I plugged “Metropolis” and “Associated British Picture Corporation” into Google together.

Nothing.

So I plugged “Metropolis” and “ABPC” into Google and got a hit,

a hit that slapped me right in the face, because it was from the book I had typeset some 20+ years ago!

I had had the answer all along and didn’t even know it.

Enno Patalas, writing in Minden & Bachmann’s book, stated on page 115:

|

In the same year [1983] we received yet another version from the National

Film Archive (NFA) in London. This version was incomplete in a different

way; it was 2,602 meters long and made from another copy of the

version that the Associated British Picture Corporation (ABPC) had distributed

and left to the NFA in 1961. Obviously there had been a British

version of the film that differed from the American version, with different

intertitles and shots and sequences that were missing from the

American one — and the same held true the other way round.

|

So, that was the distributor: Associated British. Hoorah!

One more question I can check off my infinite list.

But it leads to more questions that I need to add to my infinite list.

Did Associated British place an order to Ufa’s successors to run off more prints from the negative?

(Very likely.)

Or did Associated British simply run off its own copy negative from a lavender? (Not so likely.)

Enno Patalas said that the 2,602m print was “incomplete,”

but 2,602m is 8,537', or 95 minutes at 24fps.

That is about three minutes longer than the MoMA print, about three minutes longer than the 1936 Ufa negative.

This is essentially the same as the edition shipped to Australia in 1952

and similar to the edition released by Janus Films in the US, but we’ll get to those shortly.

So, when Enno said that this was “incomplete in a different way,”

he simply meant that it was a different abridgment.

It gets even more confusing.

I should have guessed that these people knew that 76 years later I would want to check their work,

and they knew that if they played a trick on me, they would drive me batty.

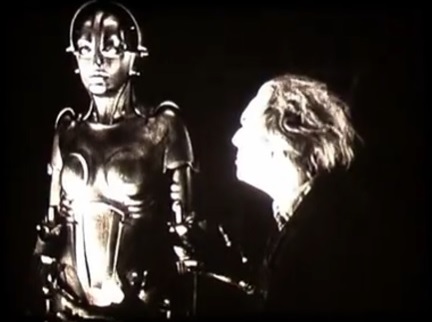

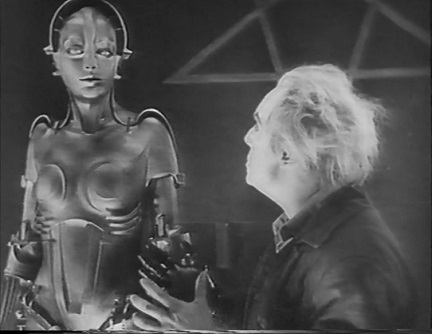

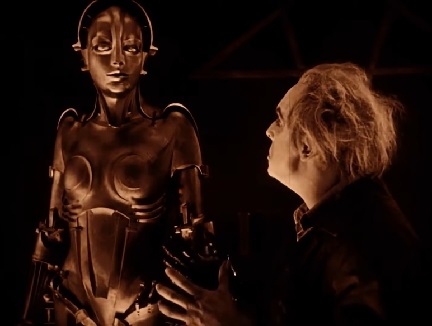

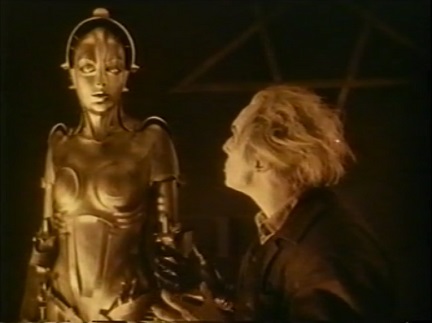

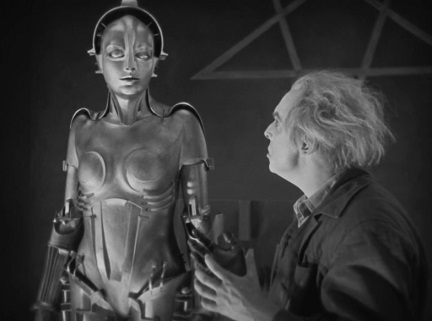

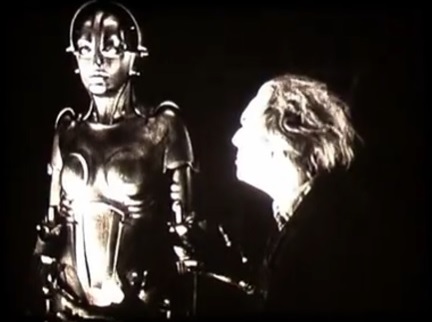

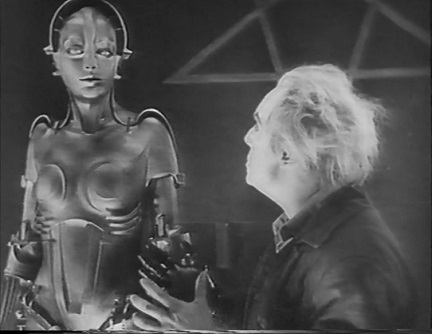

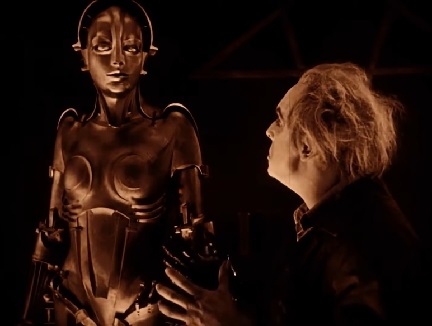

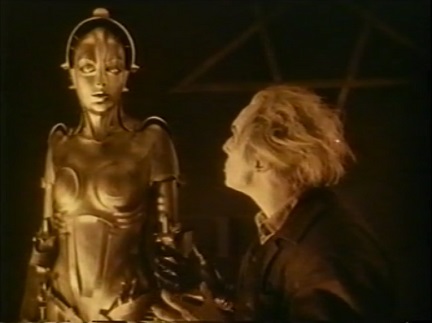

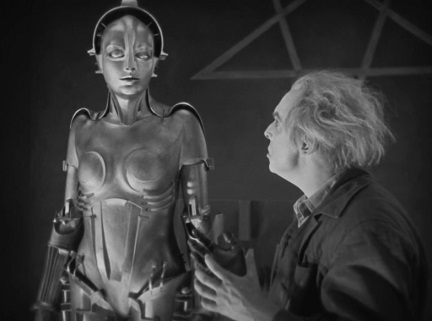

Look at the two-shot showing Rotwang giving commands to the robot.

In the preview, the robot is looking straight ahead, and Rotwang’s left hand is stretched further out than his right.

In the other three versions, the robot is turned slightly towards Rotwang, and Rotwang’s hands are close together.

This was from a different take.

It was not the Ufa take, it was not the Paramount take, it was not the export take.

What in the heckleandjeckle was it?

Where did it come from? Does anybody know?

So, yes, my postulation was right: There were more than three negatives.

1948 Associated British |

1963 Nordwestdeutscher (Ufa, German) |

1972 Staatliches Filmarchiv (Ufa, German) |

1984 Moroder (Ufa, German) |

1989 Kino VHS (Ufa, German) |

1928 Australia (export) |

2010 Restoration (Paramount, US) |

Four takes, not three. Just for fun:

Why that fourth take?

Here’s a wild guess.

What if Ufa damaged that bit of the negative and pulled a tiny roll from the can of spares for that scene?

Could that have been what happened?

I bet that’s what happened.

I cannot think of any other explanation.

Now that we’re here, let’s see what we can do.

A nitrate print is housed at the NFSA National Film & Sound Archives in Canberra, and it offers a clue!

(Canberra. Don’t feel bad. I didn’t know either until I visited.)

Did you watch the preview above?

If you skipped it, please scroll back up and watch it.

Pay attention to the music.

It sounds to me like library music.

Yet I put that thought entirely out of my mind once I read an article entitled

“The Canberra Collection: ScreenSound Australia (National Film & Sound Archives)” at Michael Organ’s

A Compendium of Resources on Fritz Lang’s Metropolis (1927) website, 28 March 2000.

This article tells us that at the NFSA archive is a composite nitrate print from circa 1951, about 8,500'.

A composite print is pieces of two or more damaged prints physically spliced together to make a single good print.

The existence of a composite print is sufficient evidence that at least two prints had gotten hammered in handling.

The music was performed by the

Queen’s Hall Light Orchestra.

This information is all too fragmentary, and pretty soon we’ll see just how contradictory it is.

It will not be easy to fill in the details and harmonize this discordant data.

As we saw above, Michael Organ provided a length of approximately 8,500', or 94½ minutes.

That closely matches Enno Patalas’s claim of about 8,537' for the Associated British print.

The Janus print I saw in 1977, which was about 94 minutes,

was certainly a newer print of what the NFSA has on file as item number 10774 at the Canberra archive!

Now, the Queen’s Hall Light Orchestra was based in London.

That’s another clue.

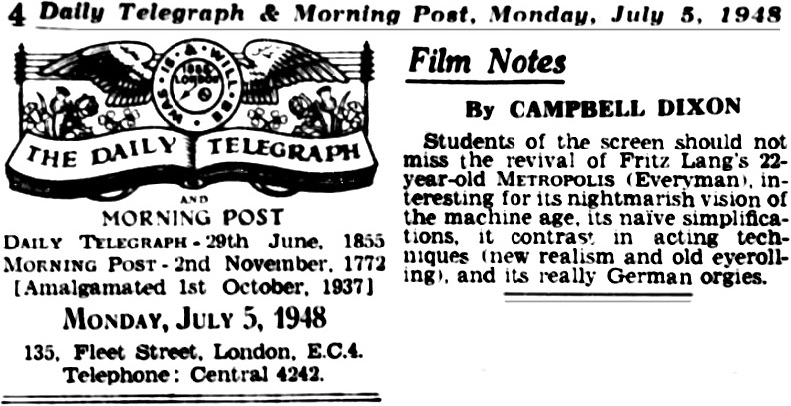

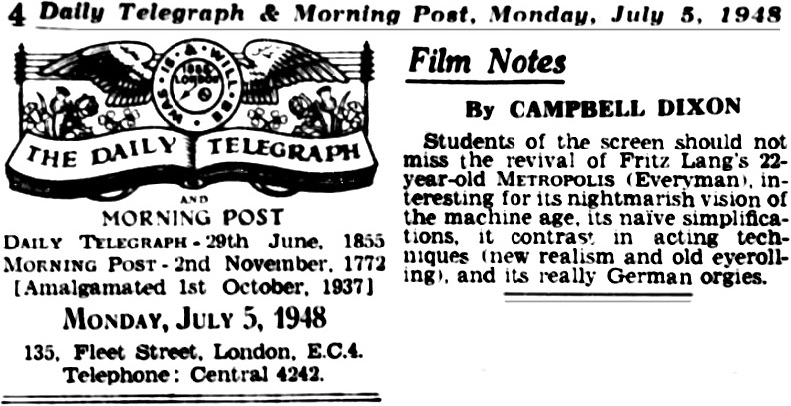

So, I hunted around the British newspapers from 1946 through 1950

and I found a news announcement that Metropolis was revived in London at the

Hampstead Everyman on

5 July 1948 and it ran for

three weeks.

Now we’re getting somewhere.

Assuming this was a custom score, then the music must have been recorded in late 1947 or early 1948,

but the composer/conductor remains a mystery.

That becomes even more mysterious when we learn that the

Queen’s Hall Light Orchestra was

a generic name for various orchestras that performed at

Queen’s Hall!

I misunderstood that claim.

When we read David Ades’s

liner notes, we learn that there was only one Queen’s Hall Light Orchestra at any given time.

So, we need to learn who the composer/conductor was in late 1947 through mid 1948.

Of course, there was no Queen’s Hall in 1947 and 1948.

Queen’s Hall had been reduced to smouldering rubble in an air raid in 1941 and would not be rebuilt,

though a substitute began construction in 1954.

So, the Queen’s Hall Light Orchestra was surely performing and recording elsewhere at the time,

but this takes me too far afield and I simply do not want to study the matter.

Whoops. I took a wrong turn and the road is getting awfully bumpy.

I heard from two experts in the field, and both have graciously allowed me to quote from their messages to me.

First, let’s hear from Tony Clayden of the Robert Farnon Society:

|

It might be relevant to mention that — as with

all publishers’ ‘house orchestras’ — the QHLO

was not a permanently constituted entity, but

a group of freelance players, most of whom

regularly performed together for the numerous

recording sessions, which often took place on

a virtually continuous basis.

Many of the musicians were members of the big

London Orchestras, and were ‘moonlighting’ to

earn some extra money. They would typically

attend a session at one of the studios in the

Capital on a Saturday morning and were able

to record a good number of pieces in a remarkably

short time. It was a case of ‘rehearse and take’, then

move on to the next one and repeat the process. This

same methodology is used today.

They were extremely good sight-readers and because they

performed this type of material so often, developed an

intuitive ‘feel’ for it.

This resulted in the many hundreds of titles

which proliferated during the ‘golden age’ of

light music production, spanning the years

during WW2 and the immediate years

thereafter, until roughly the end of the 1950s/early 60s.

|

Next, let’s hear from Alex R. Gleason of the British Film Music Encyclopædia, who brings some perspective to this matter:

|

...the only conclusion I can reach is that a soundtrack was added from the Chappell mood music library —

all cues credited to the Queen’s Hall Light Orchestra.

Chappells had well over 300 cues in their library by this time —

running to some 9 hours of material, so there would be ample music available

and the cost to the distributor would have been probably under £100 in those days.

...you say it was an ABPC release —

well, that’s really not like them at all, and overall just makes the whole thing even more puzzling!

So my conclusion —

stock library music credited to the Queen’s Hall Light Orchestra —

Music Director possibly credited as Charles Williams,

although I’ve seen a few QHLO-credited films with ‘conducted by Sidney Torch’ on the titles.

All conjecture, I’m afraid, but it’s the best I can come up with.

I am concerned about what music was used, so would also like to see and hear this version — and see the credits.

There were several fairly intelligent music editors working for the reissue companies at this time —

Peter J. Lewis for E.J. Fancey, Horace Shepherd (composer & producer in his own right), W.L. Trytel (anybody’s for the asking).

However, if it is an Associated British reissue, then I really have no idea —

Louis Levy was their director of Music —

and he was a feature film music-fitter in the 1920s (as was Charles Williams — principal conductor of the QHLO 41–46).

The

British Film Institute have a

variety of prints — as always — unviewable,

but none with a soundtrack.

I am on good terms with a variety of 16mm amateur collectors, several of whom I will be seeing in a couple of weeks,

and I’m certainly going to ask around, to see if anyone has a print with music —

it’s just possible that a few prints might have made it into the home-movie / rental world in the 1950s or 60s

and are now in private collections.

The BFI also has a

Cue-Sheet in their ‘Special Collections’

but this might be the Huppertz original from Germany or the cues for the US release,

that you’ve got well listed on your website.

I’ll order it up anyway, but this will take a month or two, and won’t help you for running time, I’m afraid.

|

I am convinced that Alex’s conjectures are largely right on the mark.

I am having second thoughts, and third thoughts, and fourth.

The music in the preview sounds just like library music, and so it is almost certainly library music,

and it would follow that all the cues used in the 1948 British reissue were library cues from mood music

recorded by the Queen’s Hall Light Orchestra and published by

Chappell.

That makes too much sense not to be essentially correct.

My oh my. Heard back from Alex Gleason, who offers one of the most wonderful messages I have ever received:

|

Thanks for the mention of the Michael Organ Australian trailer — have viewed it & managed to identify two Chappell cues.

Chappell’s Changing Scenes No.2 (iii-chase) (Sidney Torch) Chappell C.337 (QHLO conducted by Torch)

(at about 3.50 here):

Steam Hammer (Charles Williams) Chappell C 353

(QHLO conducted by Torch):

I think that clinches it!

|

Another mystery solved!

Another check mark on my infinite list of questions!

That “Steam Hammer”

piece is not the most euphonious music ever composed,

but what on earth is a steam hammer?

I went to YouTube and typed “steam hammer” into the search box.

Yipes! The music fits perfectly!

Witness: https://youtu.be/p-7bz7bmDg4.

Interestingly, Metropolis returned to the Hampstead Everyman on

Monday, 19 October 1953, and it ran for

two weeks.

That leads me to think that it did rather well the several years prior,

and there were surely a goodly number of bookings around the UK.

This was undoubtedly a 16mm print from MoMA.

Rodey, UNM, Albuquerque, NM

|