| Return home |  |

Return to previous page |

June 1972: The Eckart Jahnke Edition

for the Staatliches Filmarchiv der DDR

(wrongly nicknamed the “FIAF edition”)

for the Staatliches Filmarchiv der DDR

(wrongly nicknamed the “FIAF edition”)

As early as

1969,

Eckart Jahnke of the East German

Staatliches Filmarchiv

had begun work on a restoration.

(Sometimes you will see his name spelled Ekkehard and sometimes Eckhart.

All three spellings appear in official contexts,

but his published books give his name as

Eckart.)

When the Staatliches learned about the Soviet/Czechoslovakian project, it made a trade to get the material back.

This was part of an ongoing program of repatriation.

|

Ach! Mein Gott in Himmel!

I should have done better research!

I just found

this essay and it seemed to be based on my website.

Then I checked and learned that this was posted in

2011!

Ohhhhhh!

I could have saved myself probably 200 hours by referencing this to begin with.

Oh well.

|

|

Wolfgang Klaue was Director of the Staatliches Filmarchiv der DDR (East German Film Archive) from 1969 to 91,

a member of the FIAF Executive Committee for that entire period, FIAF President from 1979 to 1984,

and Head of the FIAF Cataloguing Commission from 1969 to 1979.

He began his archival career as Head of the Scientific Department of the Staatliches Filmarchiv der DDR (East German Film Archive),

working under Herbert Volkmann, and took over as the archive's Director in 1969.

He retained his post until 1991, when the Staatliches Filmarchiv der DDR became part of |

Jahnke’s crew members?

Nobody. He had no crew. He worked on this project entirely on his own.

Jahnke decided to use the

“London copy”

of the movie as the basis for his tentative reconstruction.

The “London copy,” he thought, was the cropped copy negative at the BFI National Film Library in London,

which in turn was derived from MoMA’s cropped lavender,

which in turn was derived from the shortened Ufa negative as it survived in 1936,

which vanished seemingly sometime during WWII.

So, this “London copy” consisted entirely of the German takes, but with English titles as translated by MoMA.

Jahnke apparently found full-aperture (uncropped) material to substitute for the BFI’s edition.

He improved the result with a little extra footage he found elsewhere in the collection.

To fill gaps, he pulled material from the Paramount and the export editions.

We should note that the Metropolis materials that the Staatliches received were entirely black and white;

none of it was tinted.

The result was about 1,000' longer than the usual prints.

Jahnke left the titles in English, but reset some of them in Arial white-on-black.

That must have been for the sake of consistency, since different sources had different typesetting.

Though he made the font consistent, he did not make the wording conform to anything.

Sometimes he used MoMA’s English titles, and sometimes Pollack’s English titles.

That is why Mr. Masterman at the opening soon becomes Mr. Fredersen.

The Staatliches must have hired a title house to remake a few titles,

for the titles that Jahnke added back in were framed for full-aperture,

whereas the titles that MoMA created were framed for an Academy crop.

That is why many of the titles are off-center to the right.

While we’re at it, we might as well learn that the film lab was

Arnold and Richter (ARRI),

I assume an East German branch, and perhaps that was the title house too?

|

In the vague hope of finding an image of Eckart Jahnke,

I went to Google and found a different Ekkehard.

Discovered that

Johann Joseph Abert (20 September 1832 –1 April 1915),

whom I had never heard of, wrote an opera called

Ekkehard, which I had never heard of,

which was inspired by the life of

Ekkehard II, a monk/poet of the tenth century,

whom I had never heard of, stationed at the

Abbey of Saint Gall,

which I had never heard of.

Just ordered a CD of the opera.

It seems that when Jahnke passed away on 8 August 1979 at the age of 41, he left behind no relatives.

Learning his life story, learning anything about him at all,

even finding a photograph of him will be

The Staatliches Filmarchiv der DDR was at

Is the building still there?

I plugged the address into

Google Maps and for some reason the building is blanked out of the photograph!!!!!!

Well, what if’n we plug that address not into Google Maps, but into Google?

We see the building!

Its name is “Am Bullenwinkel,” which reminds me of a

moose.

Google reveals gobs and gobs of photos of the restored façade that brings it back to its appearance in 1893.

Here’s one such photo from Wikipedia:

But what did it look like in 1971 and 1972?

|

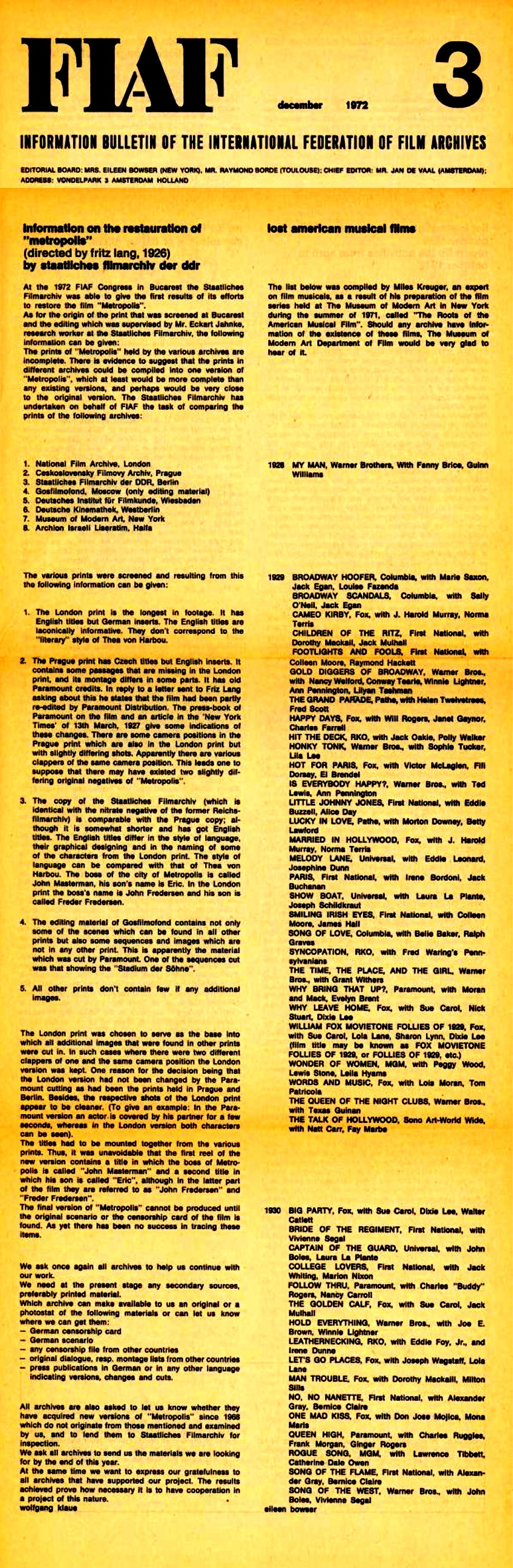

Jahnke’s early attempt at a restoration premièred at the

FIAF XVIII General Meeting in

Bucharest on the

evening of Friday, 2 June 1972,

together with some other films.

What other films? I don’t know.

Eckart’s name appears nowhere in the program, and so I assume he did not attend.

The congress seems to have been held at a hotel. Which hotel?

The screenings seem to have taken place at that same hotel, presumably in a properly equipped auditorium.

The screenings began at 8:30, but I do not have the schedule.

For short, this preliminary reconstruction of Metropolis has come to be called the 1972 FIAF edition,

even though FIAF had nothing to do with it.

FIAF just scheduled a screening, nothing more.

This is properly the Staatliches Filmarchiv edition,

or, better than that, the Eckart Jahnke edition,

but nobody ever called it that.

Everybody called it the FIAF edition.

We can stop that habit and start calling it the Staatliches Filmarchiv edition,

or, better yet, we can choose to call it the Eckart Jahnke edition.

Yes? Let’s do it.

Fritz Lang agreed that Jahnke was right to choose

“the London version,”

but there was confusion here.

What Fritz meant by “the London version” was the edition that had premièred at the Marble Arch Pavilion in March 1927,

approximately 10,695' (3,048m, or 110 minutes at 26fps),

derived from the export negative.

That was three reels longer than the 8,039' or 7,667' US edition,

and it was about two and a half reels longer than the surviving German edition of 8,307'.

Fritz was apparently unaware that “the London version” survived only in an edition that had been further abridged to 8,537'.

(A nitrate original, in black and white, is currently at the BFI National Film and Television Archive.)

That led to a misunderstanding,

for Eckart Jahnke thought that “the London version”

was the twin of the MoMA print held at the BFI’s National Film Library in London, which was derived from the domestic 8,307' German negative.

Those were two entirely different “London versions”!

Nonetheless, Jahnke based his reconstruction on the BFI edition,

supplemented with material from the export edition, which matched the 1927 London edition after all.

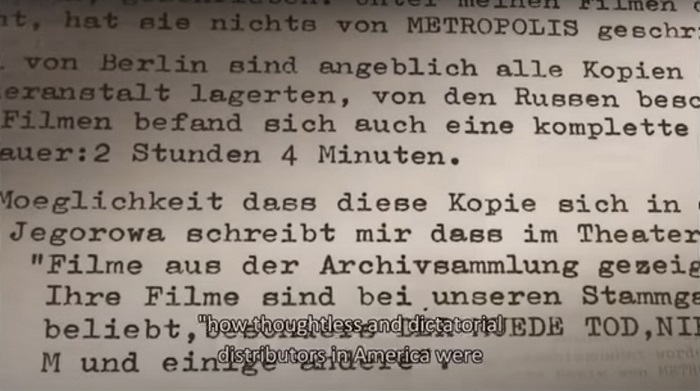

Fritz went on to state that,

“After Berlin was taken, all the copies of my film which were stored in a print lab

were apparently confiscated by the Russians.

Among these films was a complete copy of Metropolis as well.

The performance lasted 2 hours and 4 minutes.”

A frame grab from Die Reise nach Metropolis from the Eureka Masters of Cinema

Something is wrong here, and this has confused scholars and researchers everywhere.

Please allow me to unconfuse everybody, because I so clearly see what the problem is.

I am willing to bet that Fritz Lang did not mean to write “2 hours 4 minutes.”

It would make no sense for him to write such a thing.

Speeds were not locked in the silent days.

Yes, there were speed indicators, but they gave ballpark figures at best.

Yes, some critics would clock the movies they reviewed and would publish the running times down to the minute,

but the running time at the next screening might be two or three minutes different.

Larger cinemas had speed controls on the conductor’s music stand,

to slow the film down or to speed it up to keep pace with the orchestra’s performance.

NOTHING WAS EXACT in those days.

So “2 hours and 4 minutes” is a ridiculous thing to write.

It would make much more sense to write “about 2 hours” or “a little above 2 hours.”

Fritz meant to write “2 hours and 40 minutes.”

He simply failed to proofread his letter, though we do see at least one correction elsewhere in the letter,

and so he and/or his secretary truly did proof it, but not well enough.

If he typed his letter, then he simply mistyped and didn’t catch his error.

But he did not type his letter.

His vision was too poor to allow him to do so.

His secretary typed the letter, and she must have misheard vier for vierzig

and Fritz was probably too distracted to check her work carefully.

Not just too distracted, but too visually impaired.

He had lost sight in his right eye while serving in WWI, and his left eye was by this time close to useless.

There is no way under the sun he actually meant to write “2 hours 4 minutes.” Impossible.

It would take a great deal to convince me that Fritz did not intend to write “2 hours 40 minutes.”

So, barring future evidence otherwise, I am going to take his “2 hours 4 minutes” as

“2 hours 40 minutes.”

Now, the movie as shown in Berlin was never 2:40,

but was closer to 2:20 at a hair above 26fps (about 98'/min.) to match Huppertz’s score.

Fine. Fritz in his letter did not write that the movie was 2:40; he wrote that the performance was 2:40,

which was correct, as there had been an intermission.

That intermission was most likely 15 or 20 minutes,

and it was not put there to give the audience a break,

but to allow the musicians a tiny respite.

Embouchures fail after a while, and other muscles have spasms.

The musicians really did need a break.

That is one of the two problems with Fritz’s letter,

and I think I have demonstrated that the problem is easy to resolve.

The other problem is:

How on earth would he know that there had still been a complete print of the film at the lab?

And how on earth would he know that “the Russians” had made off with it?

I would have no problem at all accepting that the lab kept a full-length print,

not with an intention to issue it again, but just for reference or as an emergency backup.

Actually, it might not have been a print, but a lavender.

Is there any surviving documentation to indicate this was the case?

The archivists at the Gosfilmofond never found such material, certainly —

unless maybe one of them did find it and stashed it away someplace where nobody would ever find it?

Another possibility, considering how disorganized (and demoralized) Soviet bureaucrats were:

Perhaps it was carelessly misfiled or mislabeled.

If so, it might still be there!

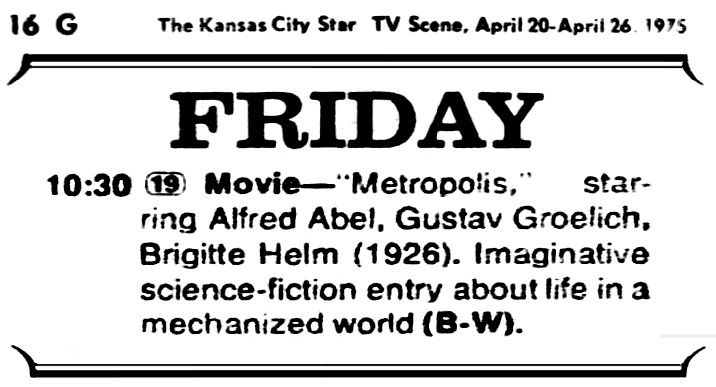

Eckart Jahnke’s reconstruction of Metropolis was not put into distribution,

but was available only to FIAF archives.

Nonetheless, somehow it ended up in distribution anyway,

and we know that for a certainty because we saw it on British and American television!

An online article called

“Staatliches Filmarchiv der DDR (Bestand)”

would lead one to suspect that the distributor was

PROGRESS Film-Verleih GmbH .

which would seem to make sense, since PROGRESS was

the only 35mm film distributor in East Germany.

Yet PROGRESS had nothing to do with the Staatliches Filmarchiv.

Actually, the distributor was the Deutsches Institut für Filmkunde (DIF) based in Frankfurt, West Germany.

How?

Well, I just learned some verified behind-the-scenes information:

In West Germany, the Murnau-Stiftung had full copyright

and legally did not need to arrange permissions with the Staatliches Filmarchiv.

So, with that knowledge in my back pocket, I can conjecture that the DIF

purchased a couple of prints from the Staatliches Filmarchiv

and simply put them into distribution, per contract solely with the Murnau-Stiftung.

Alternatively, and more likely, perhaps the Murnau-Stiftung itself purchased some prints from the Staatliches Filmarchiv

and made them available to the DIF, which had put in the highest bid.

Oh. No. I take that back.

I bet that DIF did not purchase several prints.

I bet that DIF purchased only one print.

I read the above and thought I understood it.

Then I read it a second time, some days later, and I thought I understood it.

Then I read it a third time, some weeks later, and I realized that I had completely misunderstood it the two prior times.

When I read it the third time, it struck me.

I now understood what Wolfgang was saying.

Wolfgang was right! I think.

There are two contexts here.

First, in 1972, Metropolis was not uppermost on the minds of film scholars.

It was a known title, and aficionados had seen the MoMA/BFI edition or Nordwestdeutscher’s Elfers edition,

but it was ho-hum , just another antique silent, nothing really special.

In the early 1970’s, especially in Europe, especially in Communist Europe,

silents were not considered worthy of attention,

except for a very few that could still earn a little money, for instance, movies by Buster Keaton.

It is quite likely that the FIAF audience members had never seen Metropolis before and had only vaguely heard of it.

They would not have recognized how much improved Eckart’s edition was.

What they saw on screen did not excite anybody.

It was just another creaky old silent, nothing more.

NOTE ADDED ON WEDNESDAY, 2 AUGUST 2023:

I now have it on irrefutable authority that when Metropolis was shown to the FIAF delegates

on that night of Friday, 2 June 1972,

there was no musical accompaniment at all.

Just dead silence.

Projection speed? Unknown.

Second, there is the context of the history of film restoration.

Precisely, there was no history.

Nobody had ever restored a film.

Prior to the work on Metropolis, restoration was unheard of.

A few films were occasionally revived, of course (The Birth of a Nation,

Ben-Hur , The Big Parade, Gone with the Wind, and a few others), but such events were exceedingly rare.

A change in business practice began in an unexpected way.

In the 1950’s, TV stations, desperate for any cheap material to fill their schedules,

pressured the Hollywood studios to run off 16mm prints of dead films that had no further commercial prospects.

That had the surprising effect of creating a new audience, a new audience that preferred to watch those films on the big screen.

That is why repertory cinemas began to sprout up, at first in NYC in 1960.

Studios now agreed to make new 35mm prints of negatives languishing in their vaults,

not for major reissues, but just for individual repertory bookings.

For those new prints, the standard practice was to do some basic cleaning and color correcting and repairing,

but not reconstruction.

There were a few harbingers of restoration, though nobody recognized them as such.

For instance, when Charlie Chaplin began reissuing his films in the 1940’s and 1950’s,

he could not always use the original Camera A and Camera B negatives, which had worn out,

and so he dug up the Camera C negatives as well as cans of spares to create pristine new versions.

Beginning in 1960, KirchMedia, with the blessings of Buster Keaton,

began to search archives worldwide for usable vintage prints of Buster’s movies

with a plan of reconstructing them from undamaged pieces.

Well, not really.

That was just a cover story.

The true story was that KirchMedia simply used the materials that Raymond Rohauer had gathered.

A proper reconstruction, sniffing around for missing pieces of films that had been abridged or censored or altered,

and hammering those pieces back together to create a more authentic film,

well, that was unheard of.

The one assignment that would now be considered a restoration was then just considered routine work.

MCA had acquired several Marx Brothers films as part of a package deal and wished to license them to television.

When it came to The Cocoanuts, there was a problem.

It had not been screened anywhere since the 1930’s.

The negative and fine grains had been destroyed,

and all that was left were some battered fragments together with a pirated 16mm print.

The techies stitched all the material together and created a new dupe negative

that resulted in prints that were so awful that they were almost unscreenable.

That was not considered restoration.

It was just routine work:

The bosses ordered a reissue, and the techies complied by doing what little they could with the rotten materials in their inventory.

Probably the world’s first attempt at proper restoration was done by a hobbyist,

Kevin Brownlow, who labored in his spare time to trace down the missing pieces of Napoléon vu par Abel Gance.

It was a project that has never been completed and probably never can be completed,

and it was done by an individual, not by a corporation.

Kevin would not be able to reach a stopping point to show his reconstruction until, I think, 1979.

I bet Wolfgang was right.

Prior to the unveiling of the reconstructed Metropolis in 1972,

no older film had all the king’s horses and all the king’s men

put Humpty Dumpty back together again.

This was a first.

It is hardly surprising, in retrospect, that pretty much nobody thought much of the idea —

not at the beginning, anyway.

Within a few months, though, the idea caught on everywhere.

Delayed reaction.

It was revolutionary.

The idea caught on, but the film did not catch on.

The standard MoMA/BFI/Nordwestdeutscher edition of Metropolis

continued to screen here and there at specialty houses and museums and clubs,

making no big waves, and inferior dupes were shown on TV as filler when no other programming was available.

In May 1972, Janus Films acquired from EMI a 10-year license to the Associated British Picture Corporation edition.

Remember? That was the abridgment of the Wardour abridgment

that had premièred at the Marble Arch Pavilion in London in 1927.

By now the 118 minutes had been chopped to a mere 94 minutes

and the optically reduced Academy image

was supplemented with a library score compiled from Queen’s Hall Light Orchestra cues.

The Janus release, too, played here and there, to no great fanfare,

and nobody seems to have experienced it as life-changing .

A handful of people casually attended and considered it just another “interesting” antique, nothing more.

Metropolis did not become a cult film until 1984

when a new abridgment was transformed into something resembling an MTV rock video.

It was a flop, but not a hopeless flop, because it did generate some youthful excitement that is still with us,

and Hollywood copycats earned fortunes by

copycatting Metropolis imagery in their CGI superhero extravaganzas.

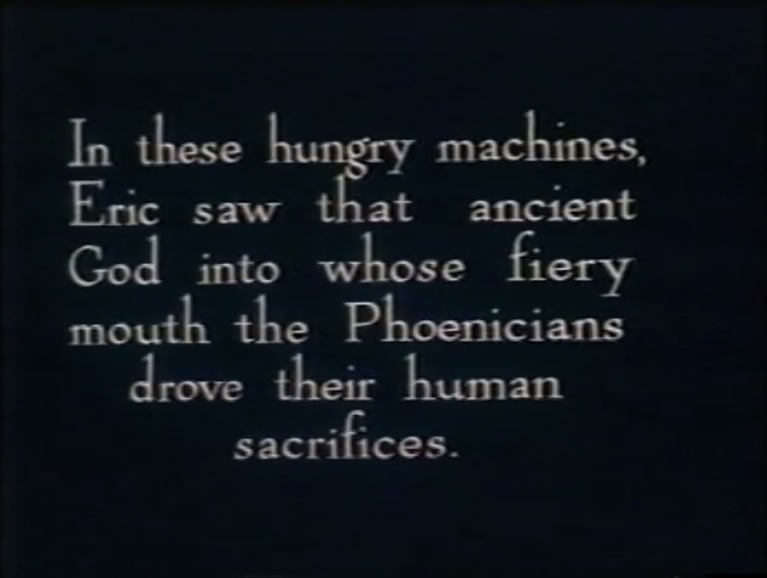

German title |

Australian title |

Staatliches Filmarchiv title |

|

Europeans still use the term all the time. Americans never use the term and have no idea what it means. Yes, it’s in the bible, but nobody reads the bible anymore, especially not Christians. | ||

Wolfgang Klaue, “Unesco and the Preservation of Moving Images,” The Unesco Courier, August 1984, p. 33.

Hand-colored version? First showing in Paris? In the summer of 1984?

Wolfgang, of course, was referring to the Moroder version.

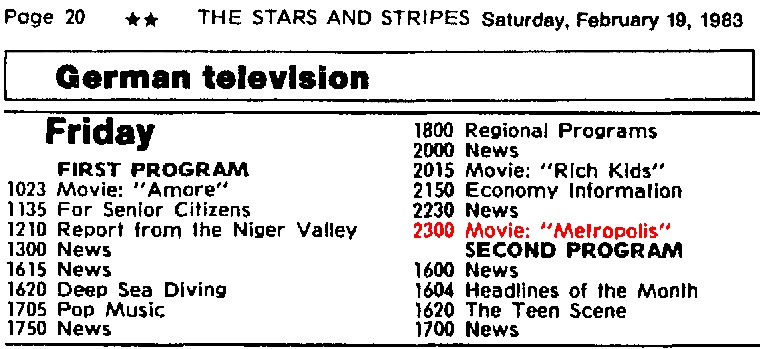

Elsaesser’s BFI Guide (p. 50) notes that the Staatliches Filmarchiv reconstruction from 1972 was

“acquired by West German television (ZDF) and has frequently been shown (and

widely circulates as an off-air recording in university film-history classes).”

Really? Really? Really? Tell me more!

When did the broadcasts begin?

Do they continue?

What speed was used in the transfer?

What music is on it?

Was this perchance the BBC2 edition from 1975?

How can I get a copy?

Please please please please please let me know!!!!! Thanks!

This is the only listing I am able to find, Friday, 25 February 1983.

There must have been other broadcasts.

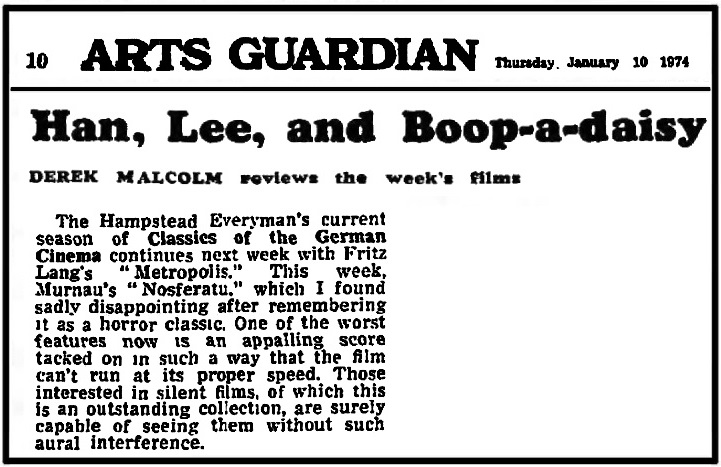

There is some confusion regarding the Staatliches edition.

Here is what we read at Douglas Quinn’s

“Yes, Virginia, there are different versions....”

Clearly the Reverend Quinn had never seen the Eckart Jahnke edition:

|

...check out some of the differences between the standard German/American release and one of the earliest East German

reconstructions of the film (circa 1969 — this is the version still frequently seen on German TV), as summarized by Michael Brunnbauer:

German/American release:

• suddenly Joh. Fredersen is at Inventor Rotwang’s house

• Rotwang gesticualtes wildly and talks with passion about his new invention, a robot, which shall replace the workers,

being worth the loss of his hand.

• Rotwang shows the robot to Fredersen. Fredersen stumbles back with horror (from his new perfect worker — not very believable).

• Fredersen asks Rotwang to decipher the secret maps from the workers.

• both go down to the catacombs.

Eastern German reconstruction:

• Fredersen comes to Rotwang’s house, because Fredersen’s experts couldn’t decipher the workers’ secret maps

and now he wants Rotwang to do it.

• Rotwang gesticualtes wildly and talks with passion about HEL,

the woman who both of them have loved and who died at the birth of Fredersen’s son.

• He holds Fredersen responsible for HEL’s death.

• He talks about a new HEL he has created, being worth the loss of his hand.

• Rotwang shows the robot to Fredersen. Fredersen stumbles back with horror

(from an artificial replacement of his dead wife — very believable).

• both go down to the catacombs.

|

There was nothing, nothing, nothing about Hel in Eckart Jahnke’s edition.

Nothing.

If something about Hel was added to the edition shown on German television, then it was added by someone else, not Jahnke.

The Hel footage was not found until 2008, in a horrid 16mm dupe neg in Argentina.

Whatever the case, I desperately want to see the version shown on German television.

Might you perchance have videotaped it?

If so, please contact me. Thanks!

NEWS.

I just discovered and read Ann J. Drummond’s master’s thesis,

Metropolis: An Historical and Political Analysis,

and she wrote something that knocked the wind out of me.

She described the three editions of the film that she examined.

The first was the BFI edition, taken directly from the lavender that

the Germans had sold to MoMA.

The next two surprised me:

|

(b) The East German (DDR) version. In 1975, the Staatliches

Filmarchiv der DDR undertook as a project of FIAF the task of

compiling a print of Metropolis “that would come as close to the

second version [i.e. the one released in August 1927, length

3241m.] as possible by using all available scenes and individual

frames of the prints from various film

(c) The ARD version. The most recent and complete reconstruction

to date was made in the spring of 1982 by the West German

broadcasting network, the ARD (Arbeitsgemeinschaft der

offentlich-rechtlichen Rundfunkanstalten der Bundesrepublik

Deutschland). The sequences and shots are identical to those in

the DDR version, but there are other major differences. The ARD

used the Zensurkarte to reconstruct the original German titles,

which is particularly significant since all surviving prints

would seem to be English language versions. The second alteration

by the ARD involved establishing the original running speed,

thanks to the discovery of the music score by Gottfried Huppertz,

which makes it clear how long each sequence should last. In

addition, the ARD prepared a new musical accompaniment, designed

to be played by two pianos: it is based on the original music

score,and leaves out the appropriate parts where visual sequences

were missing. This version of Metropolis is 1276 metres in 16mm

(equivalent to about 3190 metres in 35mm).(80)

|

As you could see from watching the PBS edition, embedded on the introductory page,

there is no mention of Eric anywhere.

Also, as you will see in the following chapter, the edition shown on PBS was 2,876m,

8m longer than the figure cited by Ann Drummond.

That is a small difference and probably insignificant,

but when we combine that miniscule discrepancy with the mention of Eric,

together with the explanatory section at the beginning, which I have never seen or known about,

well, it does make me slightly curious.

On page 187, in her section on “Women and Sexuality in Metropolis,”

Drummond explains that only the

ARD (Arbeitsgemeinschaft der offentlich-rechtlichen Rundfunkanstalten der Bundesrepublik Deutschland)

edition retains any mention of Hel.

So, Reverend Quinn was confused, and I can’t blame him, because we are all confused.

When he referred to the “Eastern German reconstruction,”

he really meant to say the West German refinement of the East German reconstruction.

But how was he to know that?

I need to find the ARD edition.

The Bundesarchiv (Abteilung Filmarchiv,

Referat FA 2 (Filmbenutzung),

Finckensteinallee 63,

12 205 Berlin,

Tel: +49 030 18/7770-8475 )

has some materials on the Jahnke edition, Filmwerks-Nr. 40034 :

| Ref # | Notes | Type | Length |

| BSP-6540 | unvollständig (incomplete) | Silent | 1010m, 3,314' |

| BSP-6911 | 5 R in 3 Bü, Material stark geschrumpft (5 reels mounted onto 3, material is shrunken) |

Silent | 1180m, 3871' |

| BSP-728 | Silent | 2350m, 7710' | |

| BSP-3474 | Reste, Szenen aus R 7,8,12 (Leftovers, scenes from Reels 7, 8, 12) |

Silent | 292m, 958' |

| BSP-2676 | Silent | 9m, 30' | |

| BSP-3284 | Restaurierte Fassung (Restored version) | Silent | 2927m, 9603' |

| BSP-5129 | Silent | 2312m, 7585' | |

| BSP-3856 | Reel 6 | Silent | 294m, 965' |

| BSP-6131 | Reel 1 | Silent | 147m, 482' |

| BSP-26581 | Restaurierte Fassung (Restored version) | Silent | 2956m, 9698' |

| BSN-4732 | Restaurierte Fassung (Restored version) | Dupe neg | 2956m, 9698' |

| BSP-9463 | Silent | ??? | |

| BSL-30541 | old Ref #: SL 00792 | Silent dupe | ??? |

| B-20137 | KT/VO: missing beginning and end | Silent | 848m, 2782' |

| B-20138 | KT/VO: missing beginning and end | Dupe neg | 848m, 2782' |

I do not know, and I cannot know, but I suspect that the 9,698' length includes about 250' of “Part Titles”

and maybe some other redundant material that was not meant to reach the screen.

Still in circulation, probably by Associated British Picture Corporation’s successor, EMI,

and the print was most likely supplied by Nordwestdeutscher,

and it most likely had the

|

Here was have a listing for a six-part series of Friday-night silent movies.

Where these prints came from, heaven only knows.

Was the Metropolis print the same one shown at the 55th Street in January 1955?

Was it the MoMA print?

Who accompanied?

Or was it the Griggs/Oderman print or the Thunderbird/Valentino print?

I don’t think there were any other options.

| ||||||||||||||