| Return home |  |

Return to previous page |

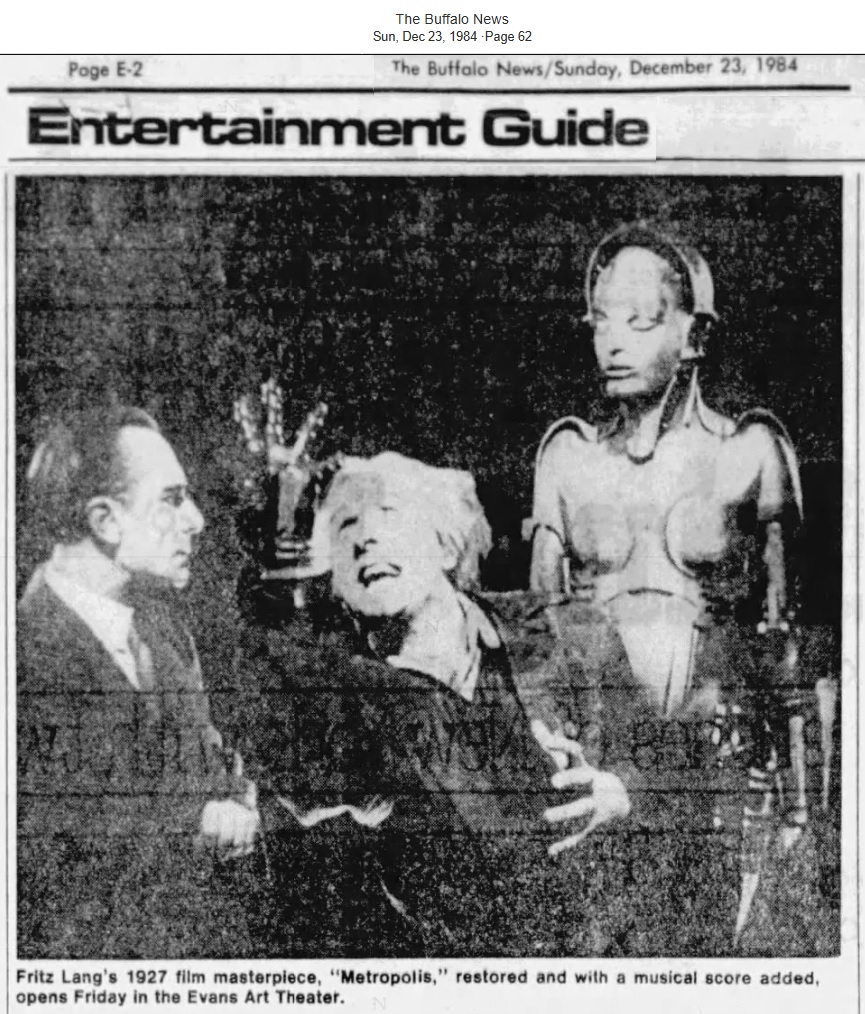

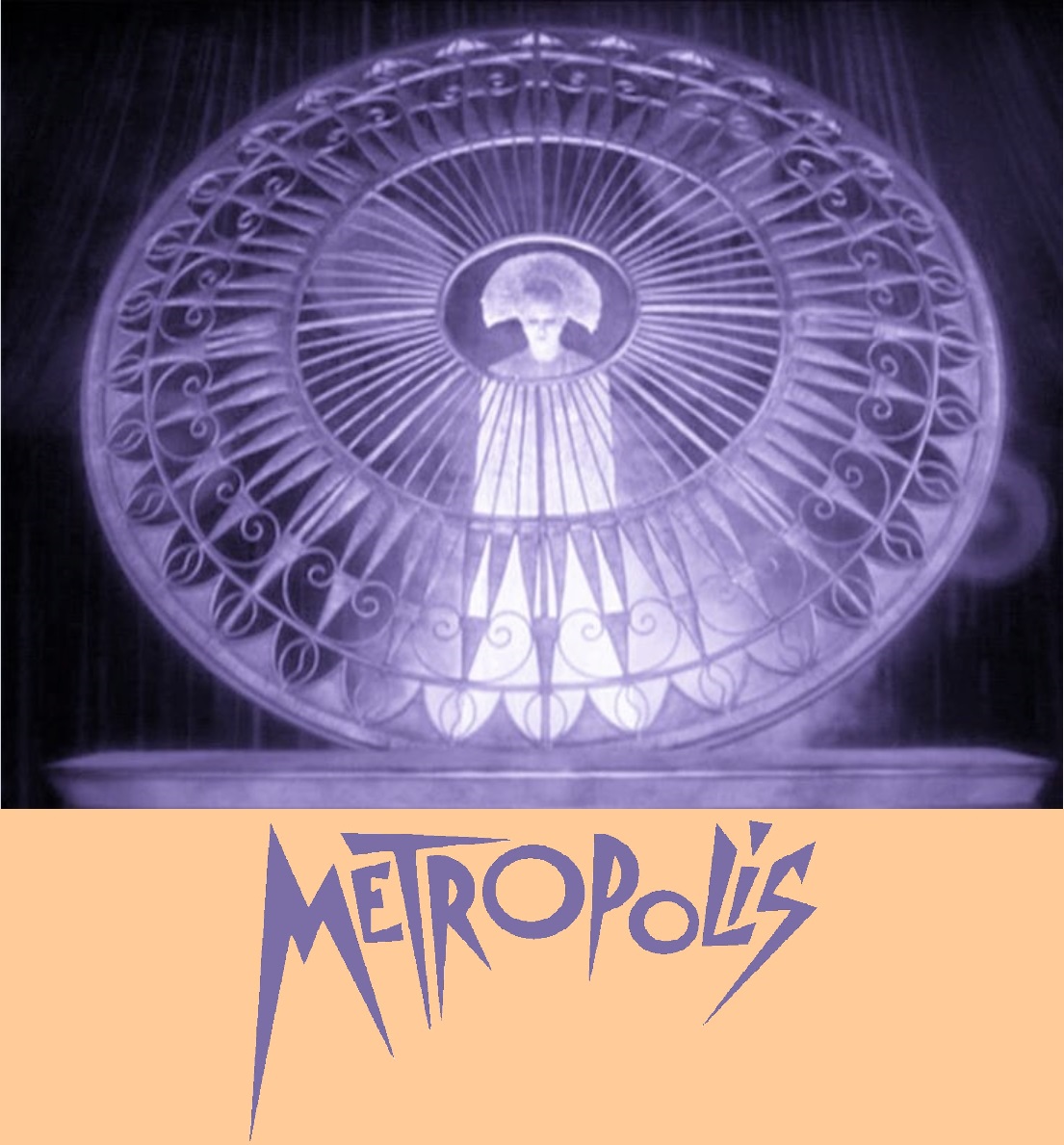

May 1984: Giorgio Moroder

Click to play.

Giorgio Moroder presents Metropolis (DVD Blu-ray Trailer)

Kino Lorber, https://youtu.be/leAVS0OC6Ts

If you’re curious, here’s one of the British versions.

Do you remember when this was announced?

I remember when it was announced.

A friend and I were chatting about it,

wondering about the claim that it was supposed to be more complete than anything seen here before,

even though it would be less than 90 minutes long.

We were both puzzled.

“Well, what about what we saw on PBS? That was a lot longer!”

Maddeningly, we could never learn where the PBS version had come from, where it had gone, where it could be seen again.

It opened with the Janus logo, but it was entirely unlike the Janus version, which made us even more confused.

It was as though it was a phantom that appeared out of nowhere and then disappeared again,

for the sole purpose of making the few people who tuned in sound delusional.

Totally maddening, totally totally absolutely maddening.

And frustrating, too.

The full story has never been told and may never be told, but here are the fragments that have been told.

First, here is what Enno Patalas said (Minden and Bachmann, p. 117):

|

In 1980, the Hollywood composer Giorgio Moroder (Midnight Express)

came to visit me and told me that he wanted to add an electronic

score to a silent film — he asked whether I had an idea — a German

one? Surely there could only be one: Metropolis.

Then, when Moroder was working on his rock music clip version, I

drew his attention to the fact that the best original material was probably

to be found at MoMA; the copy lent to Moroder by the copyright

owner, the Murnau foundation, could only be a duplicate of this material,

of the next or even the following generation. When I heard the

Ufa history of the nitrate negative from Eileen Bowser, Iris Barry’s successor

in the MoMA Film Department, and when I heard further that it

had still not been copied to safety film, I persuaded her to do business

with Moroder, to let him pay for an interim positive and then to let him

draw his negative from that. This is the way they did it. During the

next FIAF meeting she thanked me for my advice. What would happen

now to the nitrate negative, I asked her, now that she had her fine

grain? She replied with another question: “You wanna have it?”

We only had to pay for the transport to Germany back in 1986 to

have the MoMA negative of 2,632 metres, including the inserted

MoMA intertitles, shipped to the Bundesarchiv in Koblenz, which made

the copy for us that became the basis of our further work. In 1987,

Gerhard Ullmann and Klaus Volkmer mounted a 3,153-metre working

and screening copy (the “Munich version”). all material and information

we had collected was incorporated into this copy on the basis of a

montage plan that was in turn based on the piano score, the screenplay,

and the censorship card.

|

I read that passage above so many times, over and over and over,

and I thought I understood it, but I did not really understand it.

Now I think I do, though.

The Murnau-Stiftung did not have access to MoMA’s 1936 lavender, which had vanished somehow.

Perhaps it had gone up in flames?

Perhaps it had rotted?

Ufa’s camera negative had similarly vanished, probably during the confusion of WWII.

The Murnau-Stiftung had access only to the BFI’s 1939 copy negative,

which was an identical twin of MoMA’s 1937 copy negative,

and derived a duplicating positive from that to derive yet another copy negative,

thereby losing significant quality.

I assume that happened in 1966, when the Murnau-Stiftung purchased the underlying rights to Metropolis —

actually, it purchased Ufa and all its holdings outright, as far as I know.

Moroder initially sourced the Murnau-Stiftung’s material,

but Patalas told him that other material, closer to the original, was at MoMA.

Since, unlike archives, Moroder had funding,

he derived a fine grain from MoMA’s copy negative,

and then derived at least three further copy negatives from the fine grain.

He kept at least one for his own release,

and another he donated to MoMA and (probably) yet another to the Murnau-Stiftung,

and now it all begins to make sense, yes?

So, Enno Patalas, in his published account, claimed that he was the one who informed Giorgio Moroder that the Murnau-Stiftung

had only a duplicate of the MoMA copy negative.

Okay.

Well, now we dig a bit more.

Robert Harris, in a pair of postings to Nitrateville, said something different.

Witness his message of

Sun Jul 02, 2023 5:37 am:

|

C. 1981, Tom Luddy

asked me to help Giorgio Moroder locate better elements, if they were available.

I spent a day at his home, discussing the facts and fiction that I knew at the time.

I should state, loud and clear, that at no time had I ever formally researched the subject toward an attempt at restoring the film.

After viewing parts of the print that he had been sent by his licensee in Germany, it became apparent that the element

that had been delivered was a dupe of the MOMA material, with their inter-titles intact.

That bit of knowledge was able to take him back

|

|

As noted, I was involved tangentially.

I can tell you, as fact, that when I informed Giorgio that his German elements were a copy of MOMA’s he was surprised.

|

Then it gets interestinger and interestinger.

Here is a quote from Martin Koerber’s “Notes on the Proliferation of Metropolis (1927).”

(Isn’t that title funny? Translations can be dangerous.

Überlieferung more properly means transmission, not proliferation.)

|

Another nitrate copy, tinted in orange only, is on deposit from David Packard at

the UCLA Film & Television archive. I was allowed to inspect it, and it even contained

one short scene that was found nowhere else, but unfortunately the copy could never

be made available for the restoration. (The scene in question thus had to be lifted from

the Moroder version; obviously Moroder had access to this copy when he made his

version....)

|

I wish somebody would identify that sequence.

Which bit was it? Please?

This Packard print really does need to be scanned to 4K or higher and proliferated to Wiesbaden or Berlin.

Does anybody know anything about this orange Packard print?

Is it the German edition, the US edition, or the export edition?

Since it is tinted, albeit only in a single color, it definitely does not have an optical soundtrack,

and so it would retain the entire silent image.

Remember, Giorgio Moroder’s release edition was Academy aperture, optically reduced from the full silent aperture.

It was not cropped!

So it did NOT derive from the MoMA materials.

Yet Moroder’s edition derived largely from the German edition, not the US or the export editions.

So, only pieces of Moroder’s edition derived from the Harry Davidson print in Australia.

To the best of my knowledge, the remnants of the full-aperture silent German edition were all in East Berlin,

at the Staatliches Filmarchiv.

Also at the Staatliches Filmarchiv were the negative of the shortest US Paramount edition

along with a few reels’s worth of trims.

Complicated rights issues allowed the Deutsches Institut für Filmkunde (DIF) of Frankfurt

to purchase a copy of Jahnke’s edition from the Staatliches.

DIF purchased probably only one single print, and

that is the print that BBC2 transferred to video for its two broadcasts and later converted for PBS.

It does not appear that Moroder accessed or even knew about the Jahnke edition.

If the Packard print was the German edition, then we know how Moroder found the full image.

If the Packard print was the US or export edition, then we do not know how Moroder found the full image.

To summarize, Moroder’s edition consists primarily of the German edition of the film,

and only little pieces of it derive from the export edition.

Moroder spoke of using primarily the MoMA materials, which did indeed derive from the German edition,

and yet not a frame of the MoMA materials appears in his edition.

The MoMA materials are missing the left 10% of the image, but Moroder’s edition retains the full width.

He spoke also of the full-silent-aperture Harry Davidson nitrate print from Canberra, and he surely used pieces of it,

but that was from the export edition, not the German edition.

He spoke of the Packard print at UCLÁ, definitely full-frame silent aperture, definitely nitrate, definitely original,

but we do not know if the Packard print is the German, the US, or the export edition.

He spoke of 16 feet of an original full-aperture silent nitrate that John Hampton loaned to him,

but we do not know which 16 feet, and we do not know if Hampton’s material was the German, US, or export edition.

Finally, Moroder spoke of viewing a collector’s

9.5mm Pathéscope print in San Diego,

but he surely did not incorporate any of that footage into the 1984 edition.

So, I am still in the dark about what Moroder’s primary source was.

It was definitely full-aperture silent and it was definitely the German edition,

but where on earth did he find it?

Oh wait a mynoot.

I bet I know where he found it!

I bet he borrowed the material from the German TV network, ARD

(Arbeitsgemeinschaft der offentlich-rechtlichen Rundfunkanstalten der Bundesrepublik Deutschland).

The ARD had somehow acquired or borrowed some or all of the material from the Staatliches Filmarchiv der DDR,

reset the original German titles to replace the inaccurate English titles, and issued its new edition sometime in 1982.

A ha! I bet that’s what Moroder used.

I betcha, I betcha, I betcha.

If that’s the case, though,

why did Moroder pull only a few snippets from the material that was missing in all other editions?

For instance, he only hints at the Eternal Gardens,

though that scene was almost complete in the Staatliches and ARD editions.

Now that you know a little bit about the background,

it is time to ponder and reflect upon the following quote from

Chuck Frownfelter,

“The Story Of Fritz Lang’s METROPOLIS (1927),” Cinema Scholars, 25 December 2022:

|

One day, during the early 1980s,

Oscar-winning composer Giorgio Moroder

(Midnight Express, Flashdance, Top Gun, Scarface)

happened to be at home and playing some music in the background while Metropolis aired on television.

He was suddenly struck by how effortlessly the music seemed to match up with the visuals.

A strange idea suddenly occurred to him:

how it might be fun to sponsor a restoration of the film and score it with an original contemporary soundtrack.

|

It was on TV? He was in Los Ángeles at the time.

I’m curious.

|

My oh my. That was the music that was ubiquitous in my life from ages 2 through maybe as late as 9, and I never knew what it was.

All day and all night, on the radio, on TV, over the PA systems at Macy’s and at Gimbels, everywhere. Nonstop.

And in all those years, I so desperately wanted to listen to it carefully, attentively,

but I never could, not even once, because people would talk over it, or cut it off midway, or play it at whisper level.

Then, when I was 9 or so, it just disappeared.

Now I know what it is: Bert Kaempfert, “That Happy Feeling” (1962).

It was a cousin of Guy Warren’s “Eyi Wala Dong” (1956).

Both songs were descended from Georg Bürger’s

“

|

Metropolis was broadcast on

Friday, 5 September 1980, at 5:00pm, on KBSC independent channel 52 in Los Ángeles.

So far, so good.

We have a match.

Except for one problem: That’s not when Moroder saw the movie on television.

SIX MONTHS after he saw it on TV, he visited Enno Patalas, but he visited Patalas in about May 1980.

So, the sequence of events is impossible.

Fortunately, we can work out that he saw the movie not in the early 1980’s, but in late 1979, on

Monday, 26 November 1979, at 2:30pm on KBSC.

Now I wonder: Where did that copy of the film come from?

Who distributed it?

MoMA would not allow a commercial station to air its print.

The PBS license to the

BBC2 edition had expired, and I am not aware of anyone else ever licensing it.

Janus Films did not release its films to commercial television.

Griggs Moviedrome was for the most part only for home use.

That leaves two possibilities:

either Brandon Films or Thunderbird.

Since it was a two-hour time slot, we can eliminate Brandon, because

the Brandon edition was 119 minutes at 24fps,

and that would have left insufficient time for commercial breaks.

Could this have been from Thunderbird? How odd.

This is confusing, and it is only now becoming slightly clear to me.

KBSC Channel 52 was a special channel.

It was an over-the-air broadcast station, local, during the daytime hours.

At night, there was a switch, with a change of logo, to

ONTV,

the very first such station, which was just beginning to blossom into a small subscription network.

The ONTV programming was

scrambled.

Viewers who wished to watch the programming needed to pay for a subscription in order to get a descrambler,

or they had to get a 13-year-old to defeat the protections with a couple pennies’ worth of wire.

(“I

remember that all it took was a 3-foot-long piece of twin lead being attached to the 300 Ohm

connections on the TV and the regular coax on the 75 Ohm connection. You would

slowly cut ½-inch sections off of the twin lead till you attenuated the

signal of the scrambling being injected. Later you could use the little

barrel descramblers that were getting common on cable TV of the era.”)

When local programming ceased each evening, there was an announcement to the effect of,

“You are now watching ONTV. Please turn on your decoder box.”

(Here is an example.)

ONTV showed exclusive broadcasts occasionally,

but mostly it showed brand-new Hollywood movies.

Here is an example of a monthly schedule,

which demonstrates that there were just three or four programs per night.

So, was it the local station or ONTV that showed Metropolis?

The TV schedules in the newspapers let us know.

On

Monday, 26 November 1979, Metropolis was broadcast at 2:30pm, but ONTV did not come on until 9:45pm.

On

Friday, 5 September 1980, Metropolis was broadcast at 5:00pm, but ONTV did not come on until 7:30pm.

That is definitive.

It was local programming, and my best guess is that it was a

Thunderbird print.

Indeed, if it were a Thunderbird print, that would help to explain

why Moroder preferred to watch the film while he had rock music blasting on his radio.

Moroder decided to convert a German silent into something resembling a string of music videos,

and my guess is that he saw an aftermarket, or a parallel market, in issuing those songs one by one to MTV or some similar outlet.

In 1980, he asked Patalas for suggestions on which German silent would be appropriate.

Patalas, probably hoping this would lead to funding for preservation, suggested Metropolis.

Moroder was able to access two or three important sources unavailable to Patalas:

the Harry Davidson print, John Hampton’s print or fragment,

which may or may not have been the same as David Packard’s print.

As we have determined, definitively, Moroder’s edition was NOT from MoMA’s materials,

since it included much more of the original image, optically reduced to the Academy dimensions.

So it derived from full-aperture silent materials.

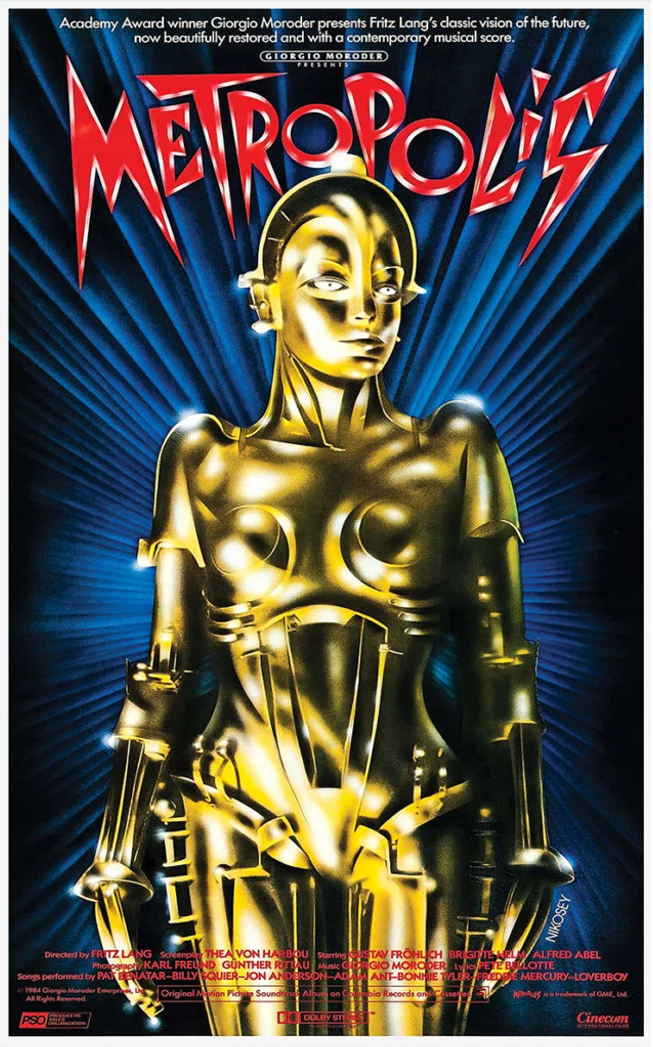

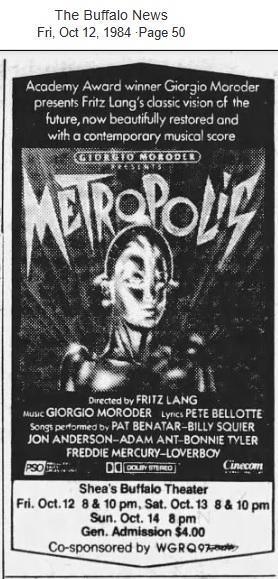

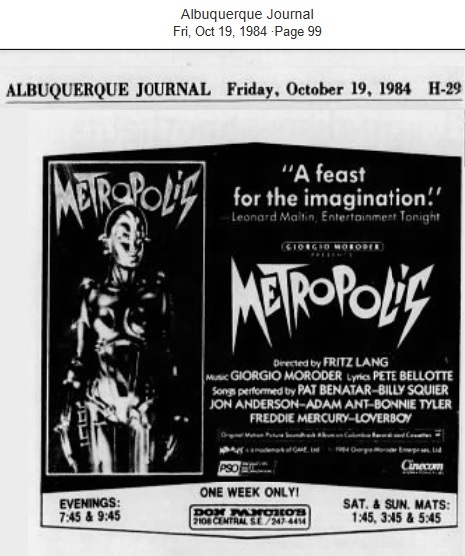

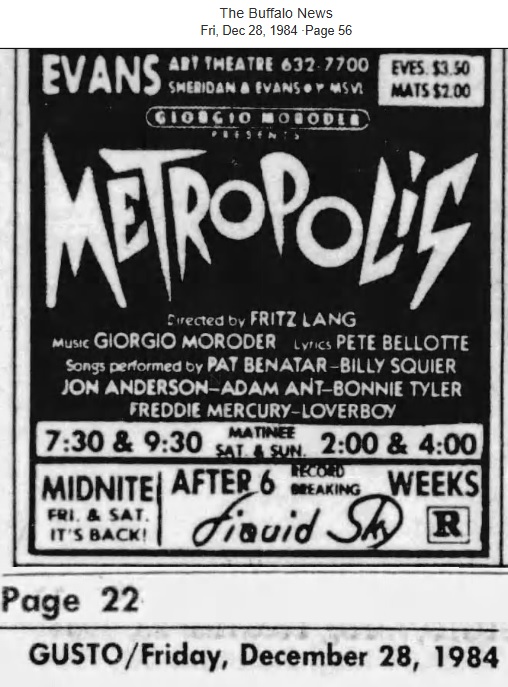

By 1984, Moroder’s revamped edition was on movie screens,

and that is when Moroder gave a different version of events.

Annette Insdorf,

“A Silent Classic Gets Some 80’s Music,”

The New York Times vol. 3 no. 46,127,

Sunday, 5 August 1984, sec. 2, pp. 15, 20:

|

...Admitting that the project

was sparked by the success of Abel

Gance’s reconstructed and newly

scored “Napoleon” — and by the suggestion

of “someone at Paramount

that I do something with a silent

movie” — he recounted the genesis of

the project. “I didn’t plan to reconstruct

‘Metropolis,’” he said, “but

the problem was the lack of a definitive

print. When I bought the rights,

all I wanted to do was put the music

on the movie.”

He first saw “Metropolis” at the

age of 17 “and then again quite

often,” he said. “I knew it didn’t need

a classical score — which I’m not too

good at anyway. Then I watched 20 silent

movies to make sure there was

nothing better than ‘Metropolis’ for

this project, and did a 15-minute

tryout just to see how it would work. I

was really excited, and started to inquire

about the rights.”...

...Six

months later, Mr. Moroder met Enno

Patalas of the Film Museum in Munich,

an expert in German silent film.

He told the composer that he found

some footage of “Metropolis” at the

Library of Canberra in Australia. “I

thought I had the official version,”

Mr. Moroder recalled, “but then I

heard of this footage and started to

read about ‘Metropolis,’ and finally

realized that I had to reconstruct it.”

After a long period of negotiation

with the Australians, he received a

videotape of their version, which contained

approximately eight scenes

that were new to Mr. Moroder.

Having learned that John Hampton,

a collector in Los Ángeles, had

an original nitrate — and therefore

chemically volatile — copy of “Metropolis,”

Mr. Moroder checked it

out, but confessed how scared he was

“because he had that footage in the

trunk and it could have exploded at

any second! But he had a few things

which nobody else had.” The next

stop was the Censorship Ministry in

Berlin, where he consulted the original

cue cards, as well as the original

score with hand notations of the conductor.

“I found that two major things

were missing,” he said excitedly.

“One is the character of Hel, which

an American editor took out in 1927

because he thought the name wasn’t

right for American audiences! I

couldn’t find any picture of Hel [the

hero’s dead mother]. By pure coincidence,

someone from the Film Museum

went to the Cinémathèque in

Paris, and in this disorganized place,

he found 400 pictures in an album.

One showed the tombstone of Hel, but

I couldn’t use it because it was a production

still and you could see the

cameraman’s head! So I recreated

the monument and filmed it.”

The second missing element concerned

a worker with whom the hero —

the son of the man who dominates Metropolis —

changes clothes. In the

files of Forest Ackerman, Fritz

Lang’s former agent, the musician-cum-sleuth

discovered a few stills

which explained where the worker

had gone: Yoshiwara, the Temple of

Sin, about which Mr. Moroder added

approximately 45 seconds with the

stills.

He remembers this period as one of

“making phone calls all over the

world, trying to find new footage. I

got a clue that a guy had

a 9.5 millimeter

copy of ‘Metropolis’ in San Diego.

I went there and found that

the copy was made with subtitles.

Somehow the movie flowed much better.

So, although this was after the

music was done, I took out all the cue

cards which had dialogue and made

them subtitles.”

|

Curious, yes?

He said he first saw Metropolis when he was 17.

So, when was he born?

On 26 April 1940.

That means he saw that movie sometime in 1957 or early 1958, and I don’t think it was in release at that time.

Did he see it at a museum or at a library?

By the way, he said he found a unit still of the Hel monument:

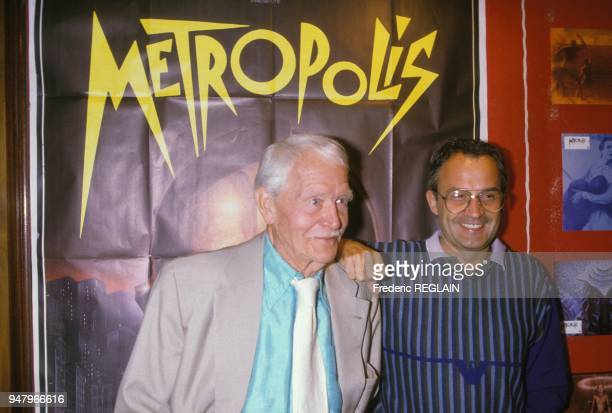

The photo that Moroder found but couldn’t use. |

Moroder’s invention. |

The true image was later found. The sculpture is a miniature inserted onto the frame by mirrors. |

Now let us hear more from Moroder, from the little insert that accompanies the Kino Blu-ray edition:

|

Growing up, I was an avid fan of classic movies and Metropolis was always

one of my favorites. A decade into my career as a composer for motion

pictures, I began a three-year endeavor to restore the film, with an eye towards

introducing it to new audiences. It was 1981, and by then Metropolis had

almost disappeared from circulation. I gathered elements of the film from all

over the world to create and restore the most complete version of Metropolis

possible (at the time)....

|

You have by now noticed that Enno’s version of events does not match Giorgio’s.

Yet it is easy to harmonize the variant accounts, and I suspect that they all do in fact fit together:

| 1957 | Moroder sees 16mm print of Metropolis at a museum |

| 26 Nov 1979 | KBSC Channel 52 (not ONTV) broadcasts Metropolis |

| ca May 1980 | Moroder visits Patalas, asks for suggestions, but does not specify Metropolis |

| ca May 1980 | Patalas suggests Metropolis |

| ca May 1980 | Moroder outbids Bowie |

Is that what happened? Heck if I know. But it fits, whether it’s right or wrong.

As we witnessed above, Enno Patalas and Bob Harris each took credit for telling Moroder that the Murnau-Stiftung edition was a mere copy of the MoMA edition.

Can we harmonize those two stories?

Maybe.

Postulation: Harris informed Moroder that the material that the Murnau-Stiftung had supplied was copied from MoMA’s edition,

and when Moroder ran that idea by Patalas, he confirmed that it was true.

Is that what happened? Heck if I know. But it fits, whether it’s right or wrong.

Thor Joachim Haga, “Keeping up the Energy — A Conversation with Composer Giorgio Moroder,”

Montages International Edition, 16 November 2015:

|

First of all, I loved the film.

It took me about two years to research.

I had a very hard time finding the prints.

The Murnau-Stiftung doesn’t have anything or very little.

The majority I got from The Museum of Modern Art in New York.

Then I found

|

So, Hampton had only 16 seconds, not the entire movie?

I’m confused.

Precisely which 16 seconds?

I’m dying to know.

Whatever happened to this fragment, or print, or whatever it was?

Does anybody know?

Is this the same as the orange-tinted print that David Packard deposited at UCLÁ?

I need to study it.

Moroder was absolutely correct that the Murnau-Stiftung had very little material on the film.

As we know, all that the Murnau-Stiftung had was the 1963 Nordwestdeutscher edition with the Riethmüller score,

from the cropped BFI copy negative,

and the 1965 Nordwestdeutscher edition with the Elfers score, which was slightly trimmed from the 1963 edition.

That was it.

The Murnau-Stiftung had nothing else, I am quite sure.

That is why Patalas referred Moroder to MoMA, which had only a cropped edition,

and that led him onto a two-year global hunt for more material.

For what it’s worth, the Eckart Jahnke edition is about 2,000' longer than the Moroder edition.

As far as I can tell, Moroder derived his edition from only three or four sources:

Davidson, Packard, Hampton (assuming that Packard and Hampton are different, and I don’t think they are),

and probably the 1982 ARD edition.

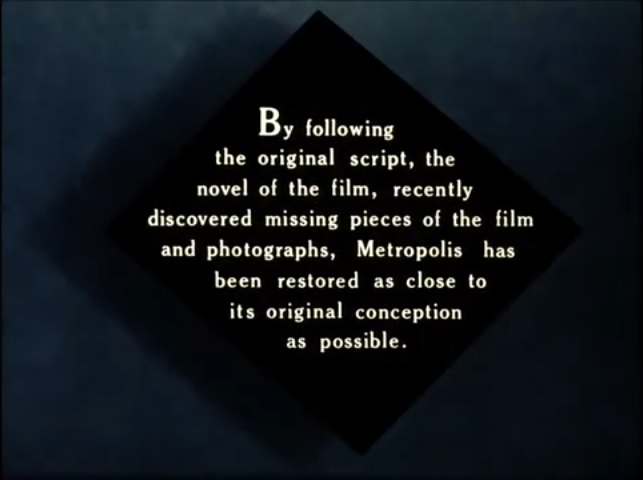

From the on-screen preface.

Misleading. Moroder’s version was streamlined,

numerous shots were deleted, and a great many shots

were trimmed and