The Famous “Deleted” Scene

THE ACCEPTED WISDOM is that the preview version was much longer, three full reels (about 30 minutes) longer.

Total crock.

To “prove” this point, a few scholars have pointed out some of the following seventeen unit stills.

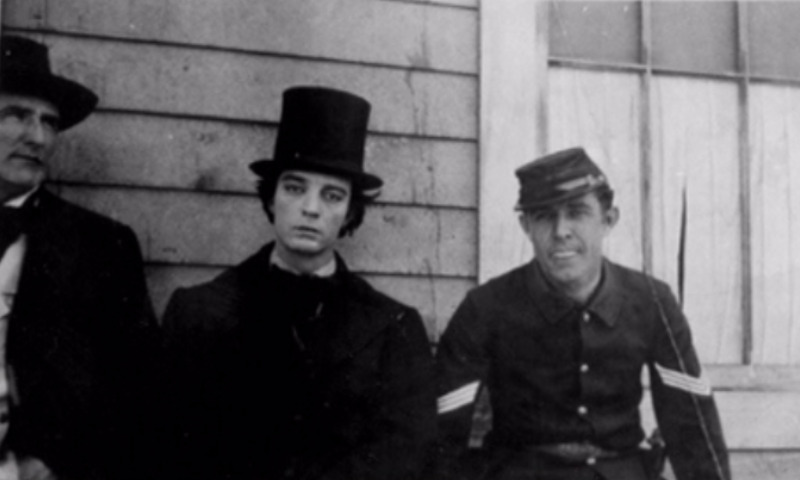

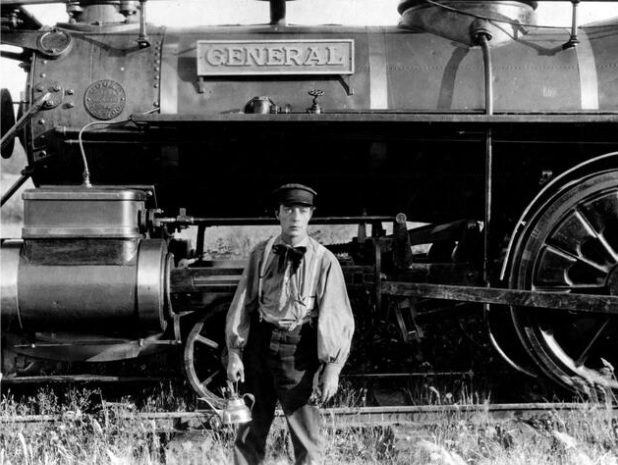

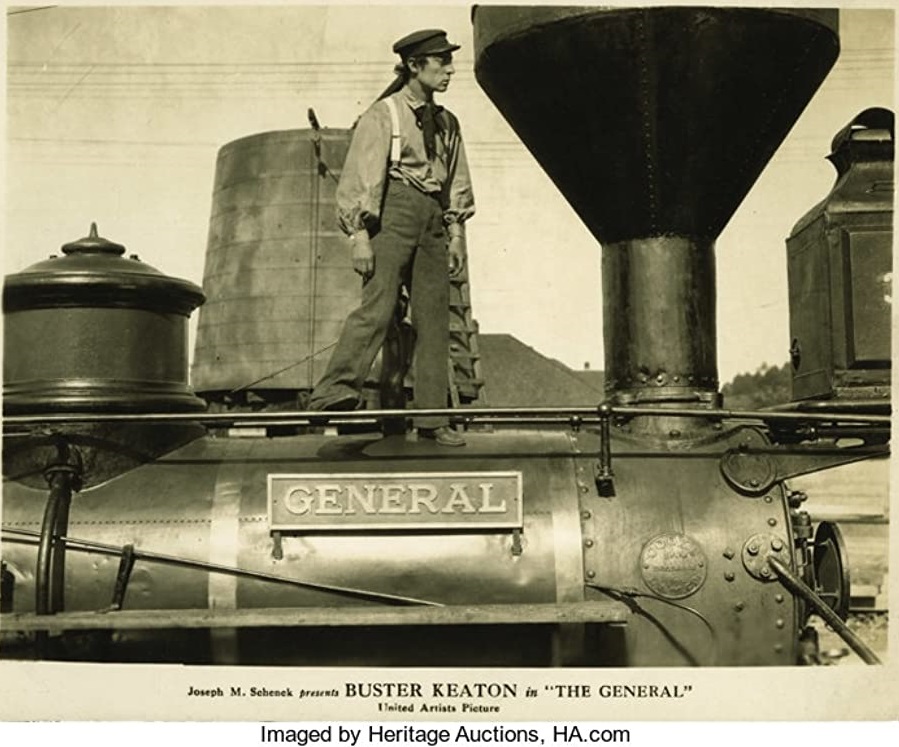

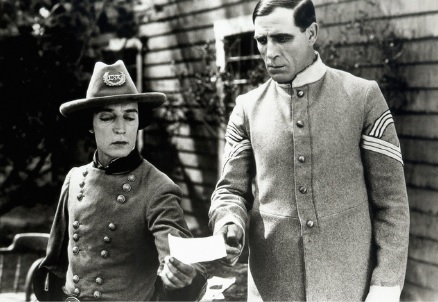

We have here a unit still of what was probably Buster’s first attempt at creating a middle of the story.

Buster shot most of the chase scenes first,

and only afterwards did he try to figure out how to link them together.

First he tried a complicated scene.

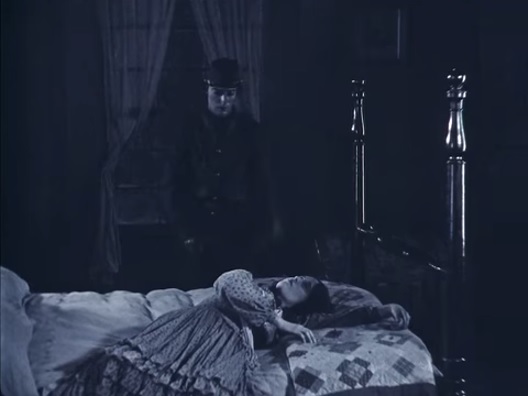

He began by having Johnnie discover a black overcoat and top hat in the cab of the Texas.

Johnnie uses them to disguise himself as a Northerner.

He walks into town and heads in the general direction of a tobacco shop.

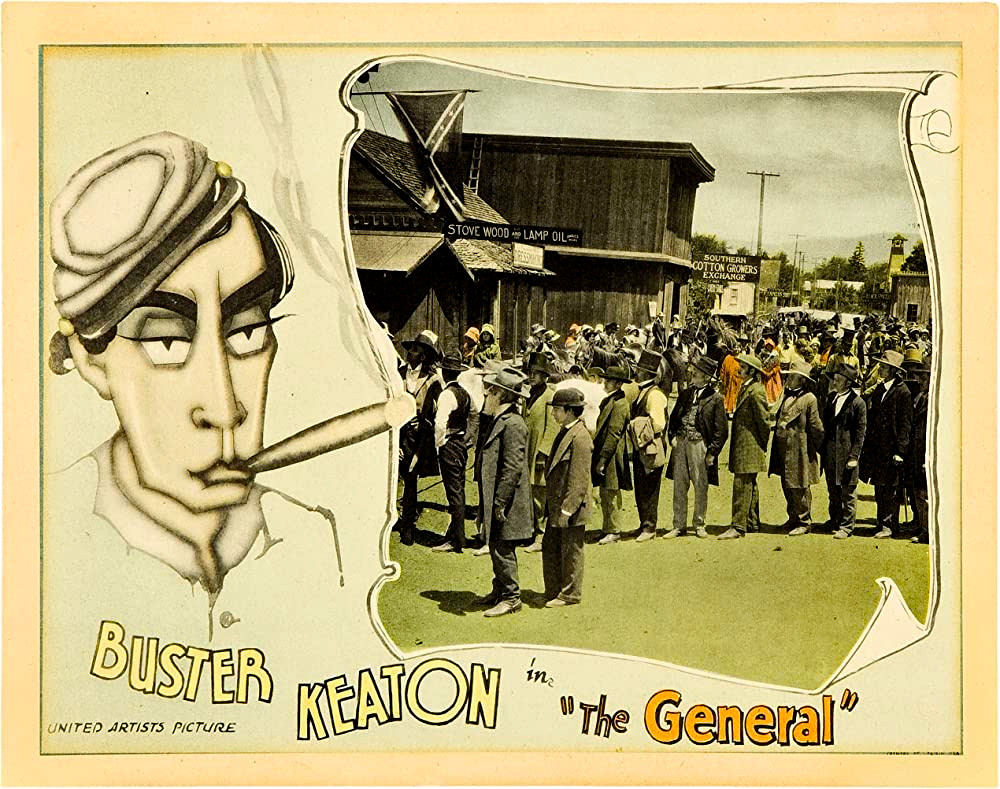

This town was later used as Marietta,

but it is here being used as a Northern-held town just outside of Chattanooga.

He goes entirely poker-faced when others arrive to say Hi.

Everywhere he turns, a Union soldier wants to make friends with him.

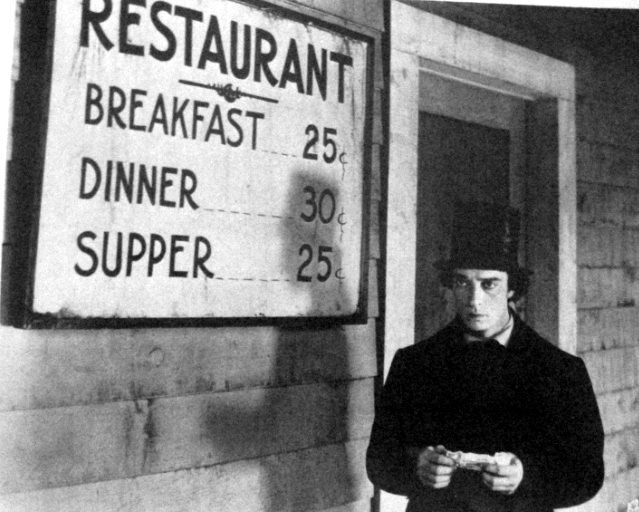

There is enough cash in the overcoat pocket to allow him to enter a restaurant.

Johnnie finds himself joined at table by the great

Snitz Edwards.

The waitress is terribly suspicious of the stranger in town,

because, after all, who on earth would dress in a black overcoat and top hat just to get a casual lunch?

According to

Kate Lewis,

the waitress was Gene (Woodworth) Barnes

(or perhaps Jean Woodward?,

or perhaps

Gene Woodword Barnes?).

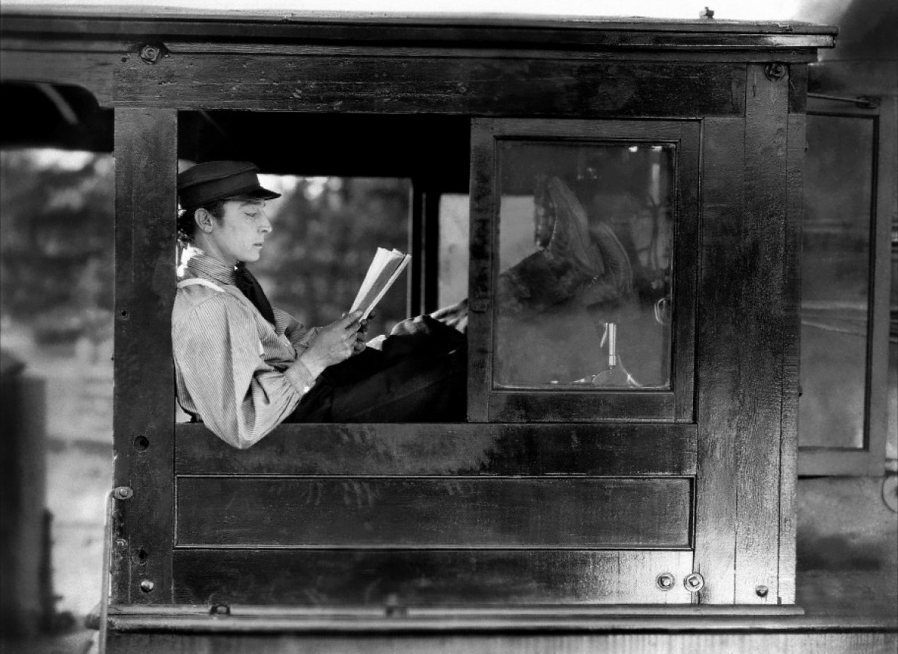

All right. Wait a minute. I’m looking at Kevin Brownlow’s book again.

She was a chorus girl from NYC who went on location to learn about filmmaking.

Her name was Gene Woodward and she told Kevin that this particular shot was just a test, nothing more.

She never appeared before the movie cameras on this or any other Buster film.

That’s a bit surprising, since this image fits the rest of the scene so well,

but if she said it was just a test, then maybe it was just a test.

Odd that such a test would be used as publicity for the film.

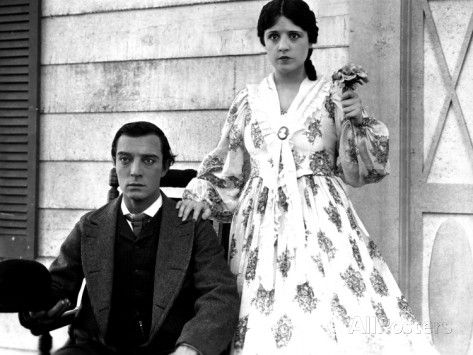

Was she perhaps hired partly to serve as Marion Mack’s stunt double?

If so, her services were never required; Marion did all her own stunts, willingly or otherwise.

It was on location that 16-year-old Gene met Harry Barnes, and ten years later she married him.

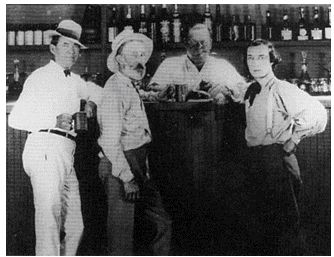

Look at that bartop in the background and the products on display behind it.

Doesn’t that look remarkably like the behind-the-scenes shot above showing Roscoe Arbuckle as the bartender?

Interiors were built on the Keaton lot at 1025 Lillian Way in Hollywood,

but this one interior, filmed while Buster was inventing the story on the spot, on camera, was certainly filmed in Oregon.

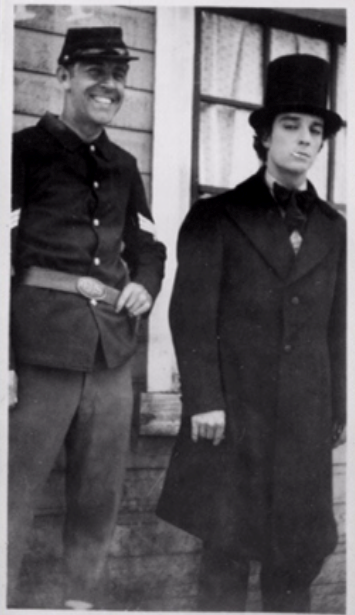

Captain Anderson, probably clued in by the first soldier and maybe by the waitress,

rushes in to seize Johnnie.

K27-163

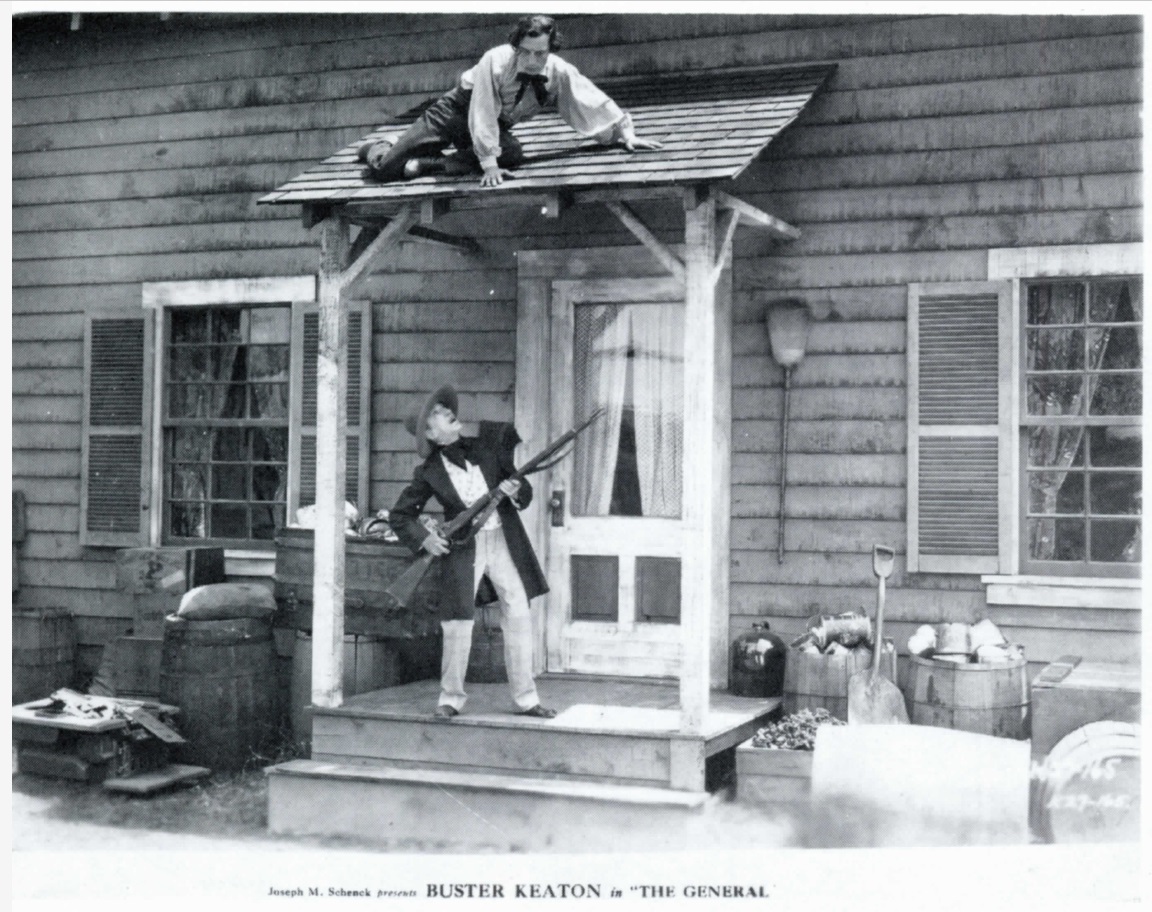

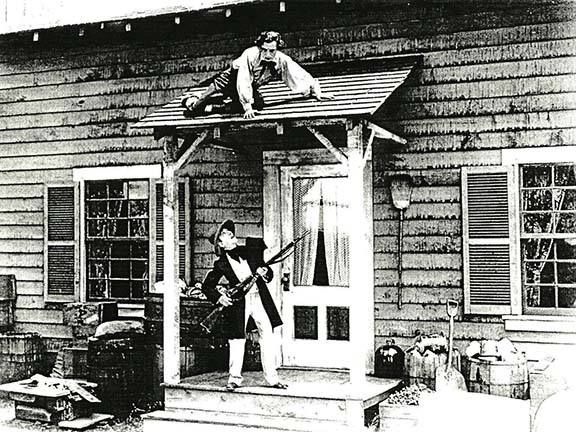

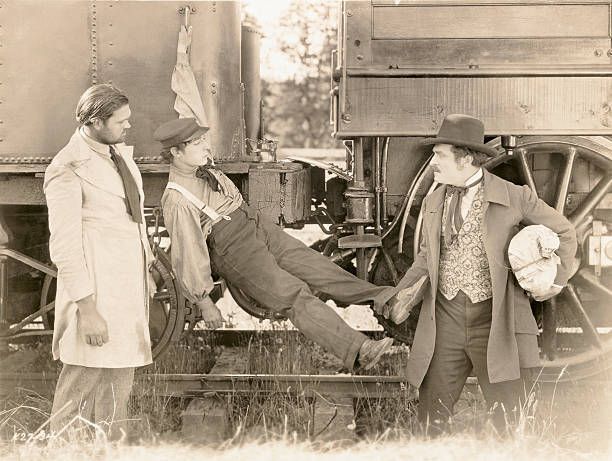

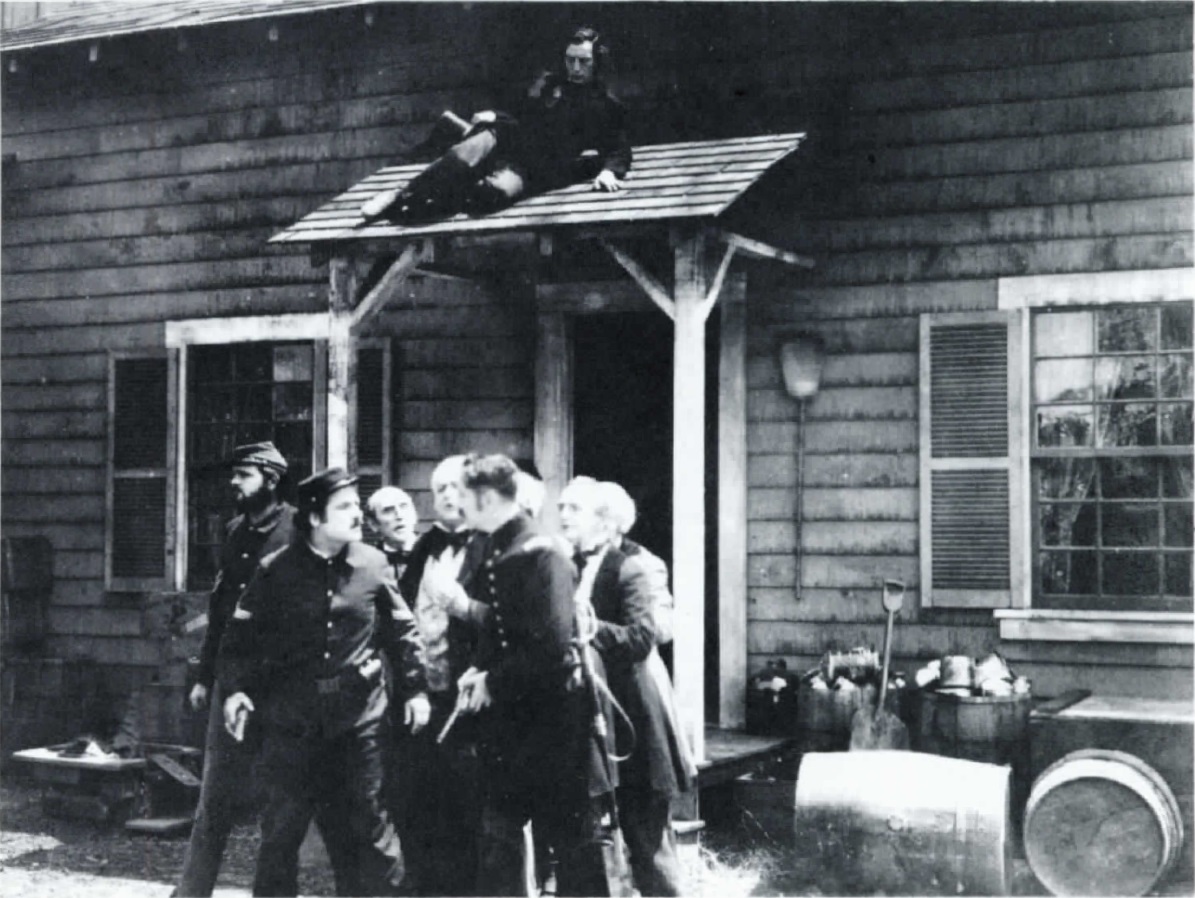

Johnnie somehow evades capture and hides on the wooden overhang.

In the final film, the Union rendezvous looks quite like this building,

as it was built on the same plan.

Actually, it was probably a different section of the same building.

Why is the negative number K27-166L rather than K27-166 ?

My guess is that the L indicated that the still would be used on a lobby card.

Buster didn’t like this scene and perhaps he never completed it and never printed the takes.

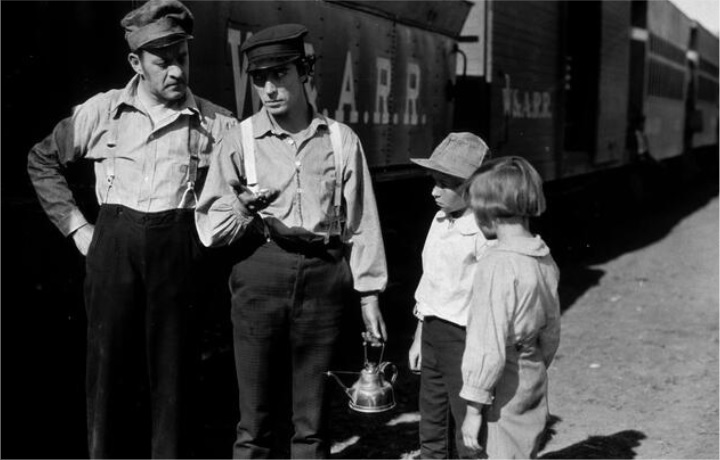

He tried again, this time more simply, just with Snitz Edwards:

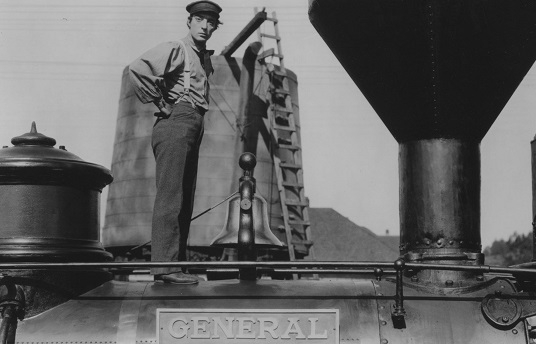

In the still above, we see that Johnnie has entered a Northern-held village just outside of Chattanooga,

still wearing his give-away engineer’s outfit.

He is hunted by a single Northerner, portrayed by Snitz Edwards, who has noticed that he is hiding atop the overhang.

This scene was not working.

Buster abandoned this attempt, sent Snitz home, and tried something new.

Note that this is the costume he would wear later in the shooting,

when he would film his visit to Annabelle’s house.

He gave this up and tried a different approach.

Some local detectives, brothers, wearing laughably obvious fake moustaches, get the idea that something is up.

Johnnie, recognizing that he is under suspicion, goes poker-faced.

(One of those two brothers, by the way, would soon appear as an extra in College.)

K27-184

Fight, flight, freeze? Freeze.

Not only is Johnnie as immobile as a marble statue, so are his pursuers.

He then gave this up and tried again, without the black vest.

Brother Number Two in the opening of College.

Can anybody identify him?

K27-189

Johnnie wonders if his drink is spiked.

Johnnie wonders if his drink is spiked.

The above seventeen unit stills are from four different sequences that Buster clearly abandoned.

Each was a failed attempt at creating a middle for the story.

It is obvious, more than obvious, why Buster junked this footage.

It didn’t have the singular drive of the rest of the story.

He did not want the story to wander, to shift gears.

He wanted a concentrated, focused, single line of narrative, without any meandering.

After he filmed four different middles of the story, he got a brainwave.

He soon realized that it would be better, tighter, neater if the refuge he sought happened to be the Union rendezvous.

So, that is what he did instead.

At last, he knew how to film the middle of the story,

and once he had figured that out, he filmed it on location,

in the restaurant/PO/general store/recruiting office.

He followed that up with Johnnie and Annabelle helping dress General Vroom in battle gear and mount him on his horse,

and he also filmed the arrest of General Thatcher, since both took place on the exterior of that set.

Despite what the written evidence suggests, he did not film the Union rendezvous upon his return to his 1025 Lillian Way studio in Hollywood.

As for the above four different restaurant sequences, they were NEVER included in the film, not even in the early test screenings.

They were likely never even completed.

Now that he decided to junk all four of these attempts,

he was free to recycle Main Street as downtown Marietta.

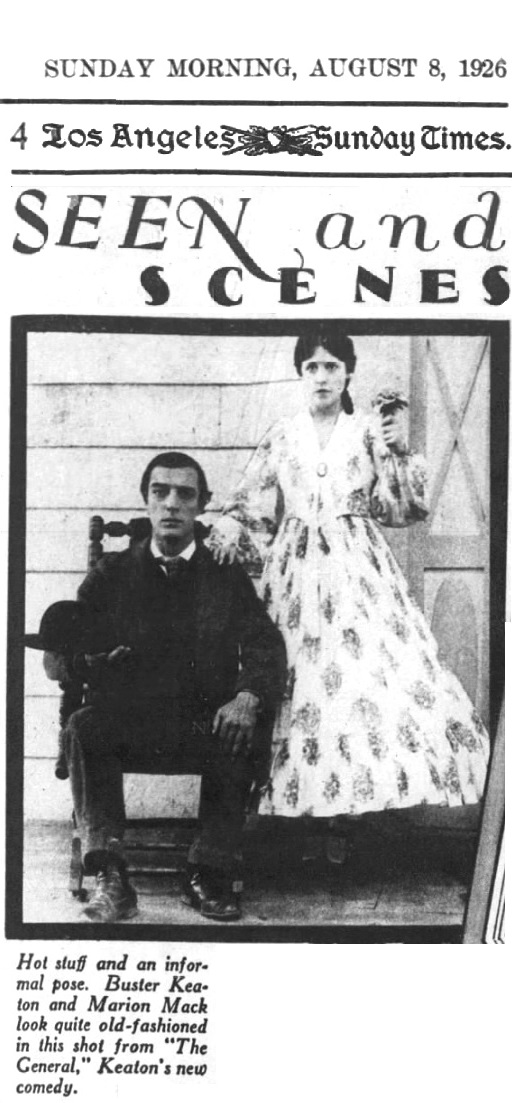

He now junked his original introduction,

underneath the locomotive, riding with Annabelle on a bicycle built for two,

having a photographer take a portrait of him and his ladyfriend.

All that was now gone.

He reshot the opening scenes in an entirely different way,

much simpler, much more direct.

Looks like the same set to me!

This set was certainly built in or near Cottage Grove, not in Hollywood, and it was fully functional.

A different portion of this interior,

or more likely a similar structure but roofless,

was used at the beginning for the General Store/Post Office/Recruiting Station.

Back in the 1990’s, I decorated my office with reproductions of several of these stills,

but I had no idea how they were to have fit into The General.

I enjoyed gazing at them and wondering, hoping someday to learn more.

I would soon meet Tracey (Doyle) Goessel, who was also puzzling over this.

Tracey published an article about a bunch of these stills, and she came up with some theories.

They were really clever theories, but they didn’t explain everything and they didn’t quite fit together.

“That Stoevpipe Hat: The Story of The General’s Abandoned Sequence,” The Great Stone Face, 1996,

pp. 17–23 .

I read her article several times in quite some excitement, and that is when I began to get headaches.

I began to puzzle over these stills, too, for weeks and weeks and weeks.

What I scribbled onto this web page is the best I can do at the moment.

If I can ever find more source materials, I’ll have better explanations.

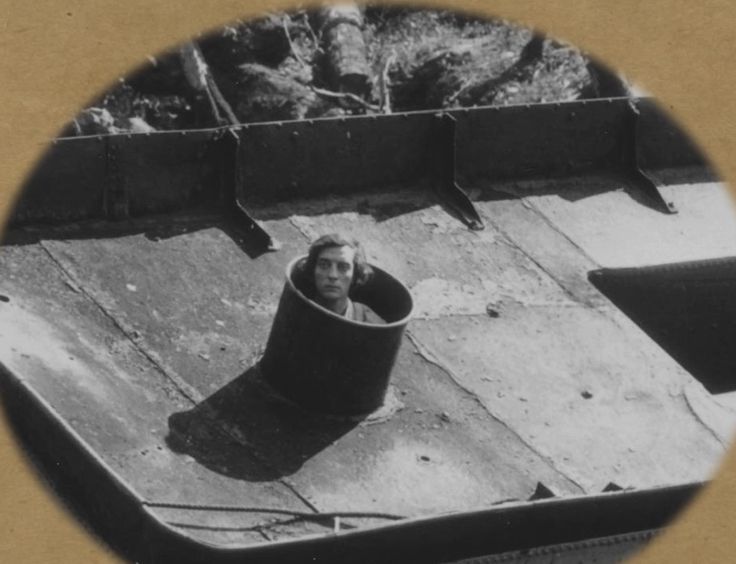

Once Buster dumped this latest attempt at a middle,

there was no further reason to introduce the black overcoat and top hat,

and yet they are still introduced.

Why did Buster not reshoot the extremely brief locomotive scene in which he discovered that costume?

It’s not as though he had lost access to the trains or to the location by that time.

As a matter of fact, he was still in Cottage Grove and still had more scenes of the trains to film.

Very puzzling indeed!

Instead of reshooting that scene,

he invented a new scene in which he ditches the costume.

Very, very puzzling, indeed!

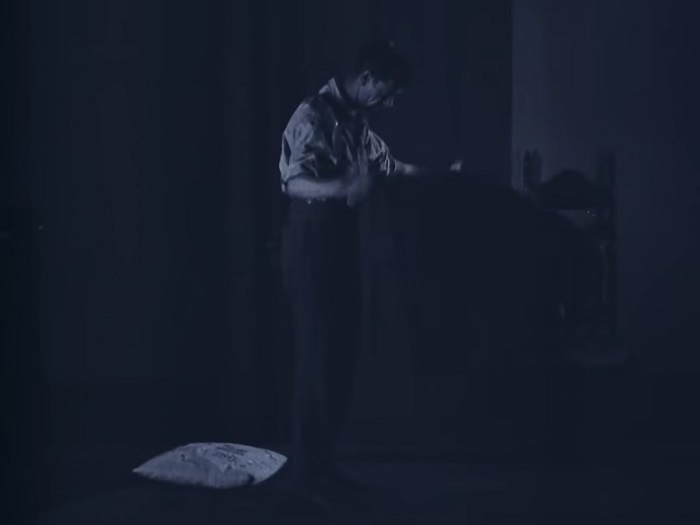

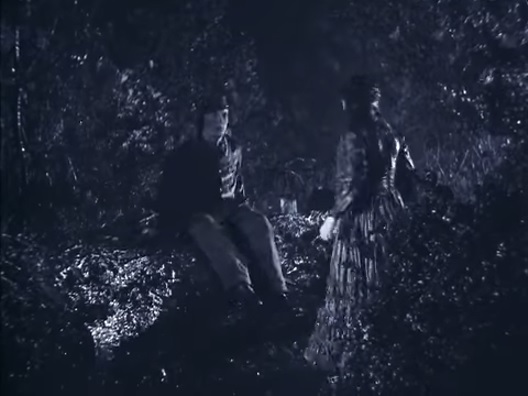

Unexpectedly, the scene in which he ditches the costume was shot not on location,

but on a forest set at the 1025 Lillian Way backlot in Hollywood.

I strongly suspect that Buster did indeed shoot an equivalent scene on location,

but that he decided to do it again when he returned to Hollywood.

Spooked, Johnnie will momentarily ditch the overcoat and top hat.

This was shot at the 1025 Lillian Way studio.

Why didn’t he reshoot the engine scene to omit the discovery of the overcoat and top hat?

I’m thinking about that. A lot.

I begin to think that he planned to, but then thought better of it.

I bet he liked that little nonsequitur;

it added just a touch of flavor, a hint of someone else’s life.

I betcha.

Begin to think?

I’m still thinking.

One of the aspects of the movie that most captivated me from the time I first saw it

concerns all the characters in the background who are just going about their lives.

There are countless extras in the movie, as there need to be.

Most are not individuated; they are just specks in larger crowds.

When we first see Kingston station, there was no need for us to see anything more than Kingston station.

Nonetheless, Buster showed us a bit more.

He showed us that the train there had just arrived and that passengers in the distance were alighting:

For most people, life just goes on.

There was no narrative need to show this.

If someone from production or accounting had been on location that day, there would surely have been arguments.

Buster was right to show this, though.

The activity in the background barely registers, but it does register, at least subconsciously.

(This shot is severely undercranked, by the way, in order to make it appear that the stolen General is racing.)

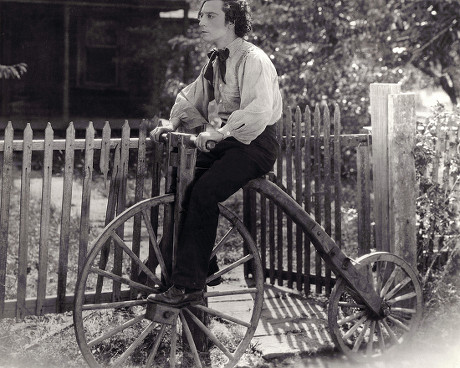

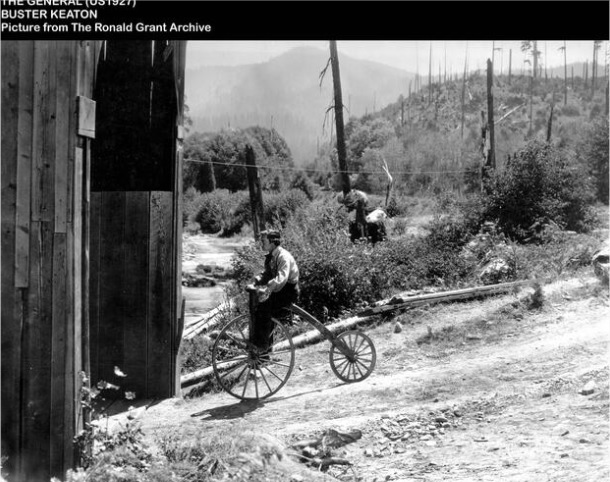

Johnnie needs some form of transportation.

By the strict needs of narrative, he could have grabbed a stray high wheel rather easily.

That was not good enough.

We should see that the high wheel (or penny farthing) has its own story.

It is pedaled by an elderly gentleman, even though the high wheel was a youthful hobby.

Clearly, this is not your ordinary everyday elderly gentleman!

He is someone special, but we see him only for the briefest moment.

It hardly matters that the high wheel was not invented until 1871.

It matters even less that this model of the high wheel was entirely apocryphal,

invented only for this movie.

This really caught my attention during that first viewing lo those decades ago.

Johnnie is clearing the track and chasing a platoon of thieves,

but a person in a yard pays hardly any attention.

Now, in 16mm, 8mm, VHS, laserdisc, and even DVD, it is impossible to tell if this is a man or a woman.

Even in the 35mm Jay Ward print from 1970 and in the 35mm Rohauer print from 1979, it was impossible to tell.

On the

Kino Blu-ray K669 from 2009, we can see that this is a woman, and I was stunned to notice a baby with her.

The baby had never been at all visible before.

Facial features? Not even the Blu-ray helps.

Just saw a beautiful DCP on the big screen, and the DCP must have been scanned directly from the camera negative,

with tons of surgery to clean up blemishes and scratches and dirt,

and I could finally see just barely enough to determine that both mommy and baby are black.

They apparently live in a tumble-down shack and are wearing clothes that are hardly better than rags.

My best guess? That was the real family that really lived there.

When mommy and baby appeared in the yard, Buster must have told them,

“Stay right there. Don’t do anything. Thanks.”

I would love to learn about them. Any clues? Anybody?

There was no need at all to show the servant washing the dishes, snuffing the candle,

angry about being compelled to sleep on a wooden floor rather than in a bed.

There was no need to invent such a character.

Yet he adds flavor.

He makes the rest of the story more human.

So that is why Buster left in the black overcoat and the top hat.

They lend the Texas a story, a human story.

The engineer of the Texas, whom we never meet, has a black overcoat and a top hat,

an outfit meant only for the most formal occasions, such as attending an opera,

and we do not usually think of train engineers when we think of opera.

Actually, to us, the overcoat and top hat seem more to belong to a villain in a melodrama.

That’s a little hint of a story, someone else’s story, someone we never see and about whom we learn nothing more.

The rest of the world continues, properly oblivious to our own little stories.

Life goes on.

Now, as I pound the keyboard in my attempts to make sense of this minimal data, I am thinking.

The first shots were, necessarily, of the over-and-under trestle at Black Rock just outside of Dallas, Oregon.

Once that was shot, the locomotives could be transported to Cottage Grove.

I am pretty much convinced that, once Buster was in Cottage Grove with the locomotives,

he decided to use the Marietta structures as the Northern-held village instead,

but before he began to shoot on that set, he changed his mind and made that outdoor set serve as Main Street in Marietta.

He shot the introduction and then he shot the chase north and the chase south simultaneously.

When the National Guard came in for six days, he shot the battle scenes.

After he finished the buik of the shooting, he tried to work out ways to connect the chase north with the chase south.

Above, we see probably four failed attempts to create a middle of the story.

What appears in the final film is the fifth attempt.

The middle of the final film has long puzzled me,

because it was conceived in fits and starts, and because,

contrary to what one would expect, the interior (Union rendezvous) was shot on location

while the exteriors (the woods outside the Union rendezvous) were shot on the 1025 Lillian Way back lot.

Shall we do some examinatin’?

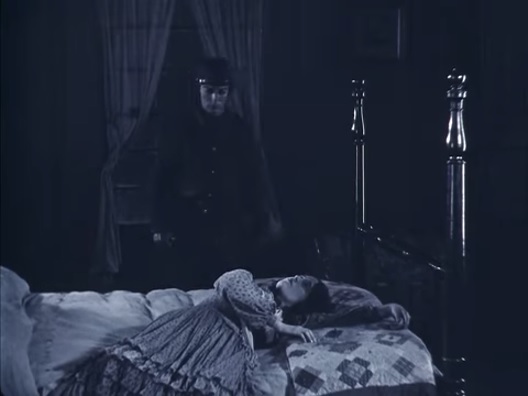

Note how similar the windows and curtains are.

The exterior on the left and the interior on the right are from the same plans.

These two images were shot in Oregon.

The dining room is on the left, and the bedroom is on the right.

They are the same room!

The beginning on the left, and a moment later on the right.

After Buster shot this as continuous action, he got an idea to interrupt it with an insert:

This insert was filmed later, possibly on a different day.

Back-lot studio set on the left, decorated to match Oregon.

On the right, a still image of a sky with animated lightning painted over it.

Left: Studio with a trained bear. Indoor or outdoor set? Right: 1025 Lillian Way. Outdoor set.

Left and Right: 1025 Lillian Way. Outdoor set.

What happened?

I bet that Buster and Marion performed the sequence on location,

and I bet it was really simple:

Just a dash to a safe spot in the woods.

After the crew completed the location shooting,

Buster and Marion performed their scenes again, with great elaboration,

at the studio at 1025 Lillian Way.

I betcha.

There is more.

On the left is one exterior wall of one building of the original Northern village set, shot in Oregon.

On the right is the scene in which Johnnie conks out a Northern sentry,

which may have been shot in Oregon or it may have been shot at 1025 Lillian Way.

I can’t tell.

That’s not all.

On the left is an exterior shot of the Northern-held village, a village on the outskirts of Chattanooga.

On the right is the same village, somewhat modified, this time functioning as Marietta.

It gets better:

Different sections of the same building (restaurant?), on the left in a Northern-held village,

on the right as it appears in the final film, as the new Division Headquarters in Marietta.

Would you like some more interesting images?

I sure want some more interesting images.

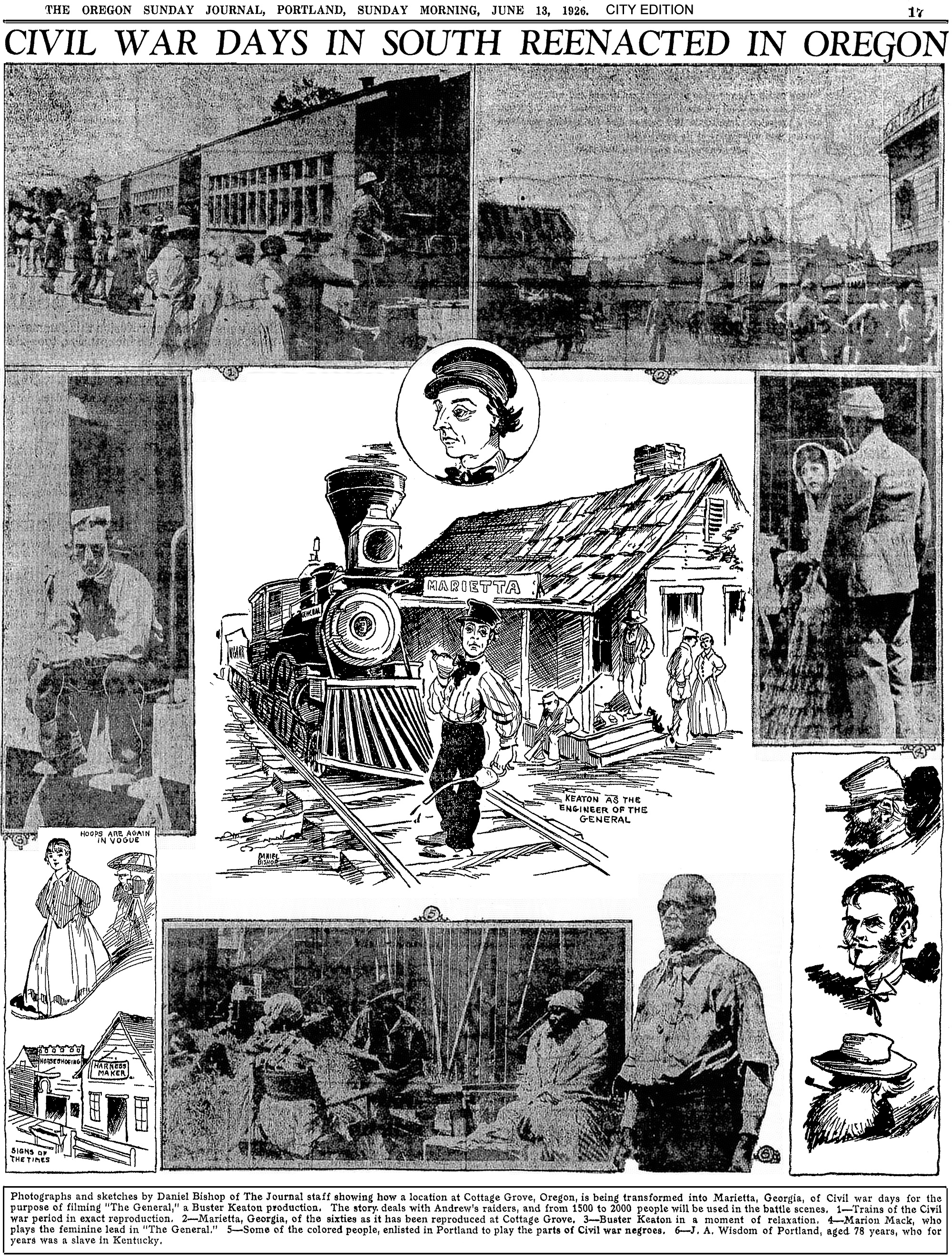

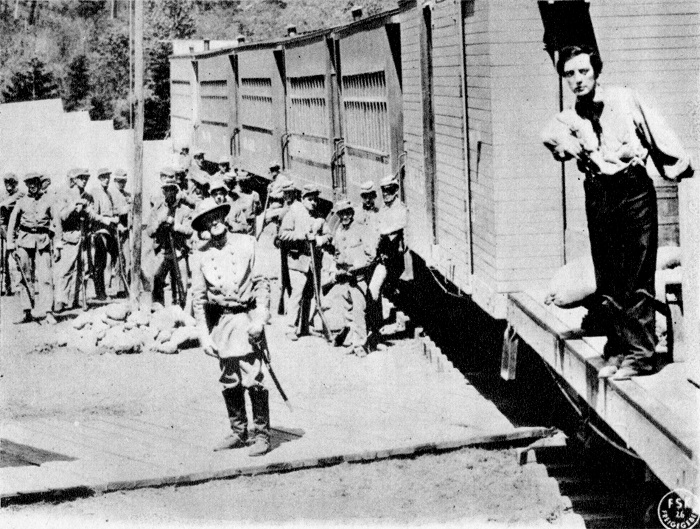

Well, we have a Portland newspaper to thank.

It shows us some extras, who, if they are visible in the final film,

they are so far in the distance that they are unrecognizable,

and that is a terrible pity.

Does anybody out there know their stories?

Especially Joseph Anderson Wisdom of Portland.

Born on 8 April 1848.

He apparently had a

slave narrative,

and I simply MUST find it somehow.

After the war, he moved to Minnesota and became a railroad porter.

In 1914 he helped to incorporate the Bethel African Methodist Episcopal Church.

In Oregon, he was

drum major of the band at the New Northwest Lodge No. 2554, Grand United Order of Odd Fellows.

He became a conductor on the Columbia River Railroad,

which was later gobbled up by the Oregon Railway and Navigation Company.

Later he became a janitor at the Post Office,

and when I worked in the Post Office, the janitors were about the only coworkers whose company I enjoyed.

Later he was a janitor in the Federal Building Custom House.

Then he went back to the ORNC.

He died on

29 November 1937.

There must be lots of rich stories, and I wish I could learn them.