The Heat Wave |

|

We need to remember that when sound movies took over, silent movies did not completely vanish.

There were a few reissues with added soundtracks — very few, of course, but still, a few.

We shall examine those later on.

Nonprofit film societies, museums, and, as we shall learn in the next chapter,

specialist 16mm screening rooms kept the light alive after a fashion.

Other silent films continued to be shown at neighborhood cinemas

and sometimes even at deluxe

|

“Paramount Screen Souvenirs” — click on the image to view This series began in 1931, and this clip is posted at https://filmlibrary.shermangrinberg.com/?s=file=418297. When this disappears from the Internet, download it. |

|

Pete Smith issued several series of shortened editions in the 1930’s and 1940’s,

and here is an example, is a clip from his series called

“Goofy Movies” (Number Four), issued on 5 May 1934.

This same clip was later included as part of

“Flicker Memories”

on 4 October 1941:

|

|

Pete Delaney, Pete Smith Does MST3K In 1941, posted on Dec 28, 2013 When YouTube disappears this, download it. |

|

And we must not forget

|

|

Gerald Santana, Flicker Flashbacks - Rare RKO/Pathé Newsreel & Silent Nickelodeon, posted on Sep 11, 2015 When YouTube disappears this, download it. |

|

A bunch of Chaplin’s silent shorts were reissued by several companies.

Here is an example of the RKO/Van Beuren series, 1932 through 1934,

with sound effects but thank heaven without any talking:

|

|

Zach Mitchell, The Cure (Van Beuren), posted on Jul 21, 2018 How I wish these musicians had been hired to score Buster’s short films. When YouTube disappears this, download it. |

|

And if you want to see something really wild,

here is what the Italians did in 1935 to their feature film of 11 years earlier:

|

|

MegaLuCiiee, Messalina 1924 (1935 sound version), posted on Jan 13, 2018 When YouTube disappears this, download it. |

|

Zo, I guess that was just the way things were done back then.

There seemed not to have been a thought about reissuing authentic editions commercially.

Even Chaplin fell under the spell when he reissued The Gold Rush in 1942,

a cropped and

|

|

This is the context in which to understand a story about Buster’s new agent,

Leo Morrison, and Buster’s longtime friend, Buster Collier.

This story, so far as I know, appears only in Rudi Blesh’s Keaton

(NY: Macmillan,

16 May 1966),

pages 352–353:

|

|

Keaton’s fine early work — the shorts and features made with his

own company and long since retired from projection — loomed as the

most feasible means of restoring the artist’s fame, stimulating new

opportunities, and bringing in needed income. Their comedy was

fresh; only sound would be needed, which could be dubbed in —

music, sound effects, and, here and there, actual speech. Although

Keaton had released all rights, some arrangement might be made.

During this period before the coming of television, Leo Morrison

and Buster Collier independently attempted to get these early masterpieces,

which dated from 1920 to 1928, released under some new

arrangement. Finally, Joe Schenck gave his substantially disinterested

consent, provided Keaton would finance the project. Once under way,

the bulk of the profits would then go, as in the past, to Schenck and,

presumably, the old stockholders, though this point was not clarified.

However, it was not entirely this far-from-equitable arrangement that

stymied the project but the unavailability on the one hand of cash

and on the other of films. For the shocking fact was uncovered that

the Keaton films had been destroyed, original negatives and all. They

had been put in storage in 1928 and 1939. During the

|

|

There is no date on that story, though, judging from the context,

it seems that it took place in 1942 or 1944 or thereabouts.

We should explore the alleged destruction of the films.

|

|

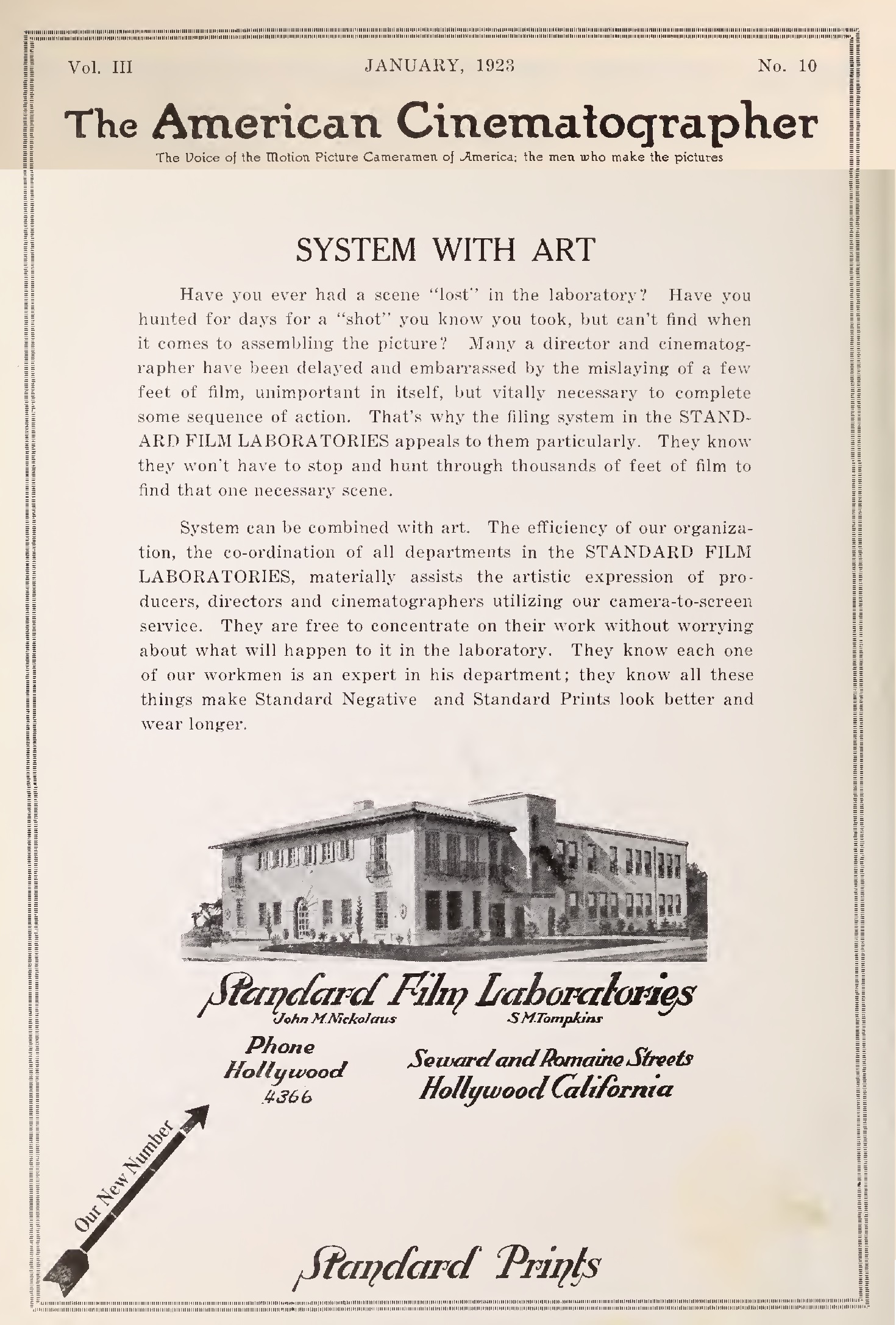

Many of the negatives of Buster’s silent films were stored at Standard Film Laboratories.

|

Interesting address. 959 Seward Street, just south of Romaine Street. That’s just four blocks east of the Buster Keaton Studio. |

|

It was sometime in the year 1958 that George Pratt of the Eastman House in Rochester, NY,

interviewed Buster, and a most fascinating interview it was.

|

_by_Georg.jpg) https://soundcloud.com/george-eastman-museum/interview-with-buster-keaton If this ever disappears (other copies have disappeared), download it. |

|

For the moment, there is one passage that should concern us, about 30 minutes in:

|

|

GP: Some people think that a good many of these early [two]-reelers are among the finest things you ever made.

I wish we could find more of them. Do prints of them exist at all?

BK: Some of them. None of these have ever been on television.

GP: Where would they be?

BK: I don’t know. I haven’t the slightest idea. I remember we had trouble one summer.

Uh, the Standard Lab had all our negatives and handled all our film work in the studio,

and, during the heat of one of our severest summers, the cooling system went out and it —.

All of those negatives just fell apart.

The emulsion just ran right off of ’em with that heat, see.

So we lost pert near all o’ our negatives.

GP: Oh, terrible.

BK: So the only thing that would be in existence would be

the, uh, what prints were out and hadn’t been run to death and all chewed up.

GP: Yeah. The positives.

|

|

With that statement, we can work a few things out.

Los Ángeles was clobbered in

September 1939,

and so that was probably the heat wave to which Buster referred.

It is impossible to determine that with certainty, though,

since heat waves with some regularity batter the Los Ángeles area.

Yet I wonder how a vault’s cooling system could fail so spectacularly

and long enough to cause the destruction of its contents without being noticed.

That seems very strange to me,

especially when we look at the illustration of the building above.

The Standard Film Laboratories was not a megaplex covering a few hundred acres,

with an unmonitored warehouse a mile away from the action;

it was a single building on a small lot.

How could nobody have noticed?

If the personnel did notice, why did they not take emergency measures to rescue the collection,

which consisted of countless millions of dollars’ worth of property

belonging to various studios, for which they were being paid handsomely

and for which they were solely responsible?

Standard Film Laboratories surely had a backup power supply and a backup cooling system.

The weather in Los Ángeles is usually rather mild, year round,

but we must remember that, despite that,

Los Ángeles is in the desert,

and so it occasionally gets blisteringly hot and sometimes it gets suffocatingly humid.

A heat wave should not have been a surprise,

and neither should a power outage have been a surprise.

Backup systems should have been in place.

Indeed, we can be certain that backup systems were in place.

Had there been no backup systems in place,

no Hollywood studio would have stored toilet paper in this building,

much less film negatives.

A mechanical/electrical failure of this magnitude should have gotten

Standard Film Laboratories sued to a fate worse than oblivion.

Yet, as far as I can see, there were no consequences for the total destruction

of decades’ worth of studio product.

Is there something puzzling here?

There sure is.

I suspect it was not any heat wave that caused the destruction.

|

|

Rudi Blesh, as quoted above, stated that

“Shortly afterward the others were deliberately destroyed, it was claimed,

because of the failure of Schenck or the stockholders to pay the storage bills.”

That claim seems much more believable.

That is a common, everyday occurrence at film warehouses.

When the storage bill goes unpaid for four or six months,

the warehouse will attempt to contact the films’ owners,

and if they prove unreachable,

the warehouse will run each roll of film through a bandsaw several times over

before tossing it into a dumpster.

Happens all the time.

It’s happening right now, as you are reading this.

|

|

So the claim that Schenck and/or the trustees declined to pay storage costs seems accurate,

or partly accurate.

When we turn to Jim Curtis’s Buster Keaton: A Filmmaker’s Life

(NY: Alfred A. Knopf, 2022) and open it to page 578, we discover that

“Studio records show they had destroyed the negatives of

Three Ages,

Our Hospitality,

The Navigator, and

Seven Chances....”

As for Sherlock Jr. and

Go West, the negatives were missing.

The negative of Battling Butler was incomplete.

|

|

Well, we know that in 1940, MGM made a

|

|

One of the most puzzling aspects of that conversation between George Pratt and Buster is that, two years earlier,

Buster, together with Rudi Blesh, Ray Rohauer, Robert Smith, Sidney Sheldon, and Donald O’Connor,

watched the bulk of those missing films,

as prints had indeed been located, and Buster had been instrumental in locating most of those prints!

The films were shown, in 16mm, at various college campuses around the Los Ángeles area (I wish I had details)

and Buster attended at least one screening.

We shall get to that story a few chapters hence.

|

|

Ed Watz posted a remarkable statement on

“What Keaton Shorts Work Best?” Greenbriar Picture Shows,

Friday, 26 January 2018:

“The original nitrate negatives of most of Buster’s initial shorts released through Metro

survived in pristine condition:

THE HIGH SIGN, ONE WEEK, THE SCARECROW, NEIGHBORS, THE HAUNTED HOUSE and THE GOAT were

‘already there’ in glorious 35mm prints when Rohauer debuted the BK Festival in the US in 1970.”

The only two Metro releases missing from that list are Convict 13 and Hard Luck,

which survive only in battered fragments that were pieced together with difficulty,

and both of which remain incomplete.

|

|

If The “High Sign” OCN survived “in pristine condition,” then I am terribly confused.

Why?

Because all the copies currently in circulation are incomplete.

Not only are they incomplete, they are not taken directly from the OCN,

but instead trace their ancestry to a projection print.

Here’s what Buster said to Paul Gallico for an article called

“Circus in Paris,” Esquire vol. 42 no. 2, August 1954, pp. 30, 108–111,

as quoted by Rudi Blesh in Keaton (New York: Macmillan,

16 May 1966, $8.95),

pp. 141–142:

But you never saw that

So far, this would seem to make sense.

We can guess that Buster revised the preview print but never made the change to the OCN,

as he was never expecting to release the film.

Yet when he was compelled to release it a year later, he either forgot about his revision or he lost the replacement footage.

Maybe that’s a reasonable guess, or maybe not.

David Robinson saw the print that Rohauer presented at the BFI National Film Theatre on 14 February 1968.

He was apparently permitted to view it several more times, probably on a flatbed, in preparation for his book.

The situation now gets more complicated.

As I have written elsewhere, the best book about Buster is the underground and privately printed

tome compiled by Oliver Lindsay Scott,

Buster Keaton, the Little Iron Man,

and if you turn to page 454, you will see his review of Kino Video’s edition of

The “High Sign”, included as part of its box set called “The Art of Buster Keaton.”

He wrote:

Oliver Scott and I had a lengthy email correspondence from 2002 through early 2004,

and, as knowledgeable as he was, and as thoughtful, articulate, and meticulous as he was,

and as much as I gratefully learned from him, he was also a pain in the neck.

He turned everything into a debate, even though there was never the slightest disagreement.

He had an uncontrollable compulsion to latch onto some word, or some form of some word,

or some syllable, or some choice of phrasing,

to force a misinterpretation in order to launch his latest round of the duel of wits.

The duel of wits was his favorite hobby, and he eagerly, zestfully looked forward to any pretext to engage in it.

No compromise. Winner take all.

And he would not let go until his hapless adversary

finally got exasperated enough to give in just to keep the peace.

That is how he invariably emerged the perennial victor.

I grew weary of those pseudodisagreements and I got tired of giving in.

It was a stupid, useless game.

So I stopped responding to his emails.

And then he died not long afterwards.

Darn it.

Then my email account was hacked, which caused my email provider to kill my account,

and then a thief stole my laptop, and I now have nothing left of any of our correspondence.

Darn it.

I wish I still had his messages, because now I need to check them.

I asked him about the print that included the

Ed Watz adds more detail.

We need to correct “prints” to “print.”

Now, isn’t this interesting?

The print shown at the BFI National Film Theatre in London on 14 February 1968

was not the same as the print shown at the Elgin in Manhattan

several times from 22 September through 26 October 1970.

Each print derived from a different source.

Do these two prints still exist?

What about their source materials?

Very confusing, and, more than confusing, utterly frustrating!

Ed Watz implies that the print shown at the Elgin in September/October 1970 was from the OCN retrieved from the MGM vault.

It would therefore follow that the print shown two and a half years earlier in London was from a different source,

almost certainly the first preview print, or, much less likely, the workprint.

And if it was the workprint or the preview print (there could never have been more than two of each),

then it could only have come from Buster’s garage

and then migrated to Ray Rohauer’s collection in the summer of 1954.

Maybe. Maybe not.

(There is now a controversy about the claim of Rohauer collecting anything from Buster’s garage in 1954.

Jim Curtis in his book, Buster Keaton: A Filmmaker’s Life, makes a rock-solid case

that Rohauer collected no prints from Buster and did not even meet him until 1958.

Well, not quite a

Another possibility, which I just came up with but which I think is a stretch,

is that the current copies of The “High Sign” are not taken from the preview print,

but are instead taken from a release print that was damaged and cuts off the second half of the revised scene.

I doubt it.

It’s from the preview print.

The prints I have seen in 35mm and on

Above is the

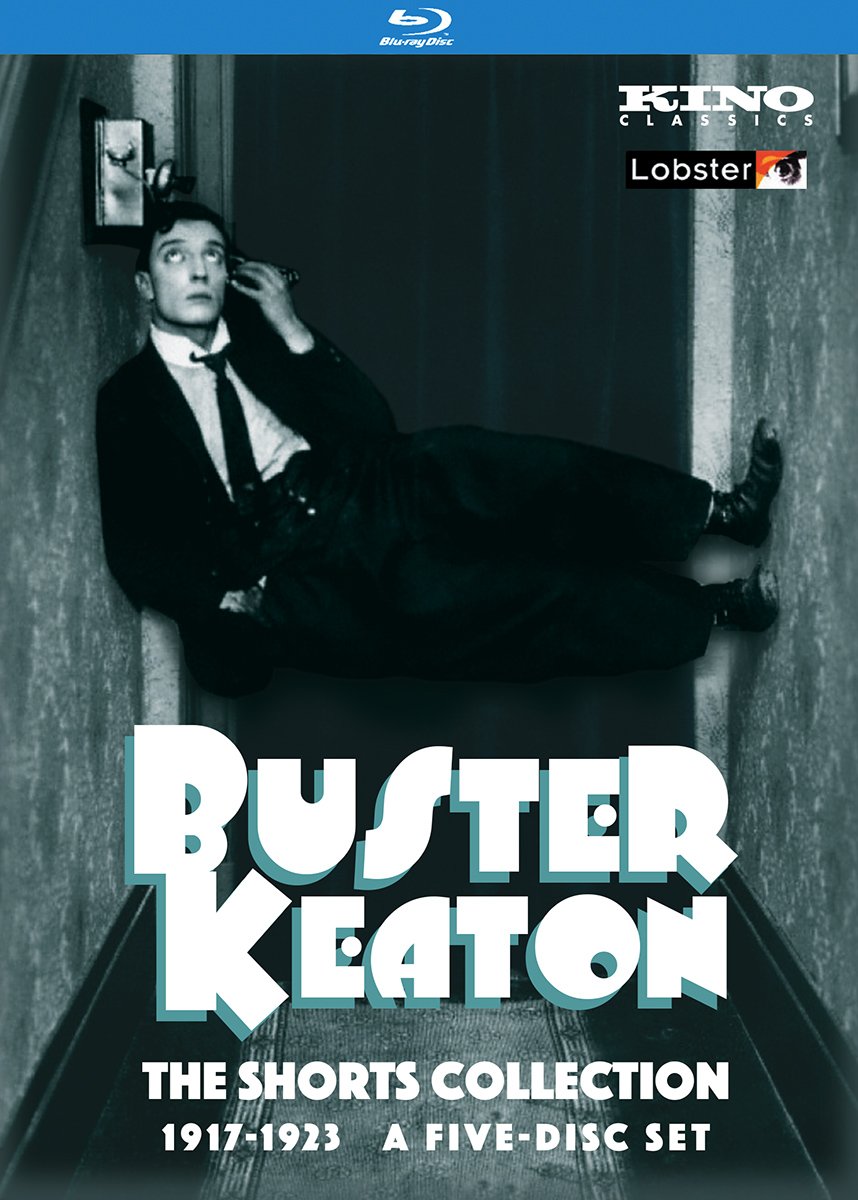

The above set, which Kino and Lobster issued on 24 May 2016, utilizes different sources.

The titles in The “High Sign” were remade digitally.

The scratches were made less visible by software that unfortunately softened the image.

I prefer a sharp image with scratches to a soft image with fewer scratches.

The cropping is less egregious and so we can see a little bit of the rounded corners.

The sources were safety fine grains copied from material that Douris had sourced.

This is definitely not from the OCN.

Where is the OCN?

Where is the print derived from the OCN?

I do not know how to solve this riddle.

My best guess is that the

On a

Oh how much I would love to examine all of these elements myself.

Oh how much I would love to see this latest restoration!

|

|

My guess is that MGM stored the negatives of Buster’s Metro shorts,

and that two of them disintegrated without any help from bureaucrats or accountants.

My guess is that Standard Film Laboratories stored the negatives of Buster’s First National films:

The Play House,

The Blacksmith,

The Boat,

The Paleface,

Cops,

My Wife’s Relations,

The Frozen North,

Day Dreams,

The Electric House,

The Love Nest, and

The Balloonatic.

Judging from the prints and videos I have seen of those particular films,

it seems to me that no masters survive.

Every print and video I have seen looks like a dupe.

Some of them look like really good dupes, but dupes all the same.

|

|

Something is not quite right with the knowledge that has been handed down to us.

I have no way of verifying anything at all.

I do, though, have an idea.

When David Shepard issued “The Art of Buster Keaton”

through Kino Video in 1995, he left in some telltale clues.

Some of the short films retained what were

|

|

On

10 April 2001, Kino issued a pair of videos, “Arbuckle & Keaton,”

consisting of 10 of the 14 shorts the duo made together.

(Why only 10 of the 14?

Because The Rohauer Collection was never able to acquire

His Wedding Night,

Oh! Doctor, or

The Cook, and nobody in the world has been able to find

A Country Hero.

That’s why.

Why did Moonshine not include the superior fragments,

and why were some of the films, notably The Rough House and Out West,

so terribly incomplete?

Because The Rohauer Collection was never able to acquire better materials,

which are held by other organizations that simply do not wish to deal with The Rohauer Collection,

at least not on these matters, at least not now.

I dream of a day when there is a rapprochement so that all the materials can be collated and combined.)

The only one of the 10 films that retained its original American titles was

Coney Island,

and it was clearly duped from a leftover release print.

The titles of the other nine were all

|

|

Any Buster movie in the Rohauer Collection with

|

|

We are thus left with a question that I cannot answer:

Who told Buster that ALL the negatives had been destroyed,

and WHY did that person or those persons tell Buster that ALL the negatives had been destroyed?

Does anybody know? Anybody? Please? Help?

I want to understand this. I really do.

|

|

My best guess is that Schenck and the trustees made a corporate decision

to cease paying rental to Standard Film Laboratories and to MGM.

It was not until after Standard had destroyed the negatives

that Leo Morrison and Buster Collier got the idea to reissue the films.

Rather than come clean, Schenck and his trustees invented the fiction

that the emulsion had melted off during a power outage in the midst of a heat wave.

Schenck and the trustees were surely unaware that MGM,

by mistake, was continuing to store the surviving negatives

and would even begin submitting copyright renewals.

As for the three pictures distributed by United Artists,

perhaps by the time that Schenck had told Buster of the fate of his posterity,

neither he nor Buster even brought up the topic.

A sense of hopelessness pervaded the conversation, I suppose.

That’s all just a big massive guess, but absent evidence, a guess is all I can make.

Buster was surely delighted to discover, in 1946, that MoMA was still circulating a 16mm copy of The General,

which he attended several times over the next 13 years or so.

|

|

As for MGM mistakenly renewing the copyrights,

Ray Rohauer was later able to use that error in court to his advantage to acquire MGM’s Buster holdings.

|