|

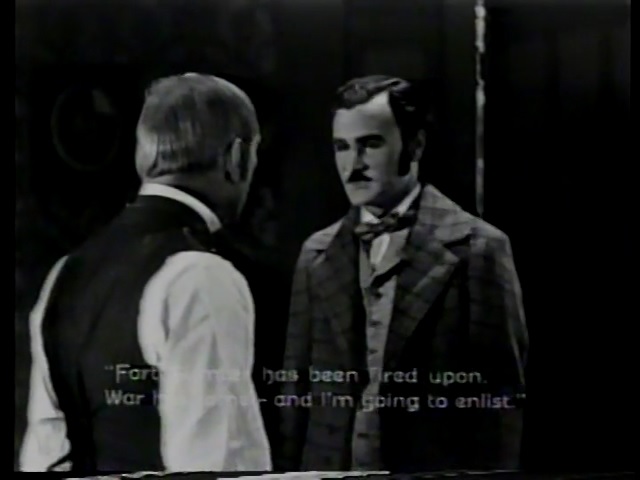

Courtesy of a collector who captured a Showtime transmission on VHS back in April 1986,

we can at long last view this edition again.

The quality of the dub is rather poor, cursed with images that are too dark and too soft and beset with time-base errors.

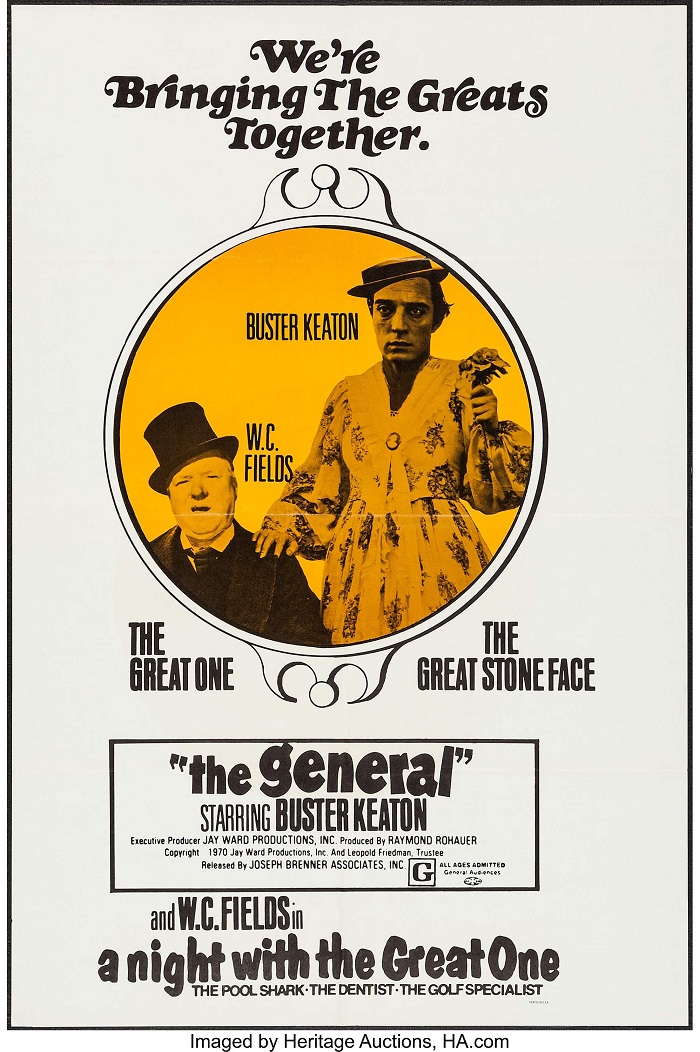

I can attest that the 35mm prints from 1970 were gorgeous, bright, sharp, clear, and crisp,

and that they made the film look nearly brand new.

Despite the faults and glitches of this dub of an off-cable VHS, the video is nonetheless a revelation.

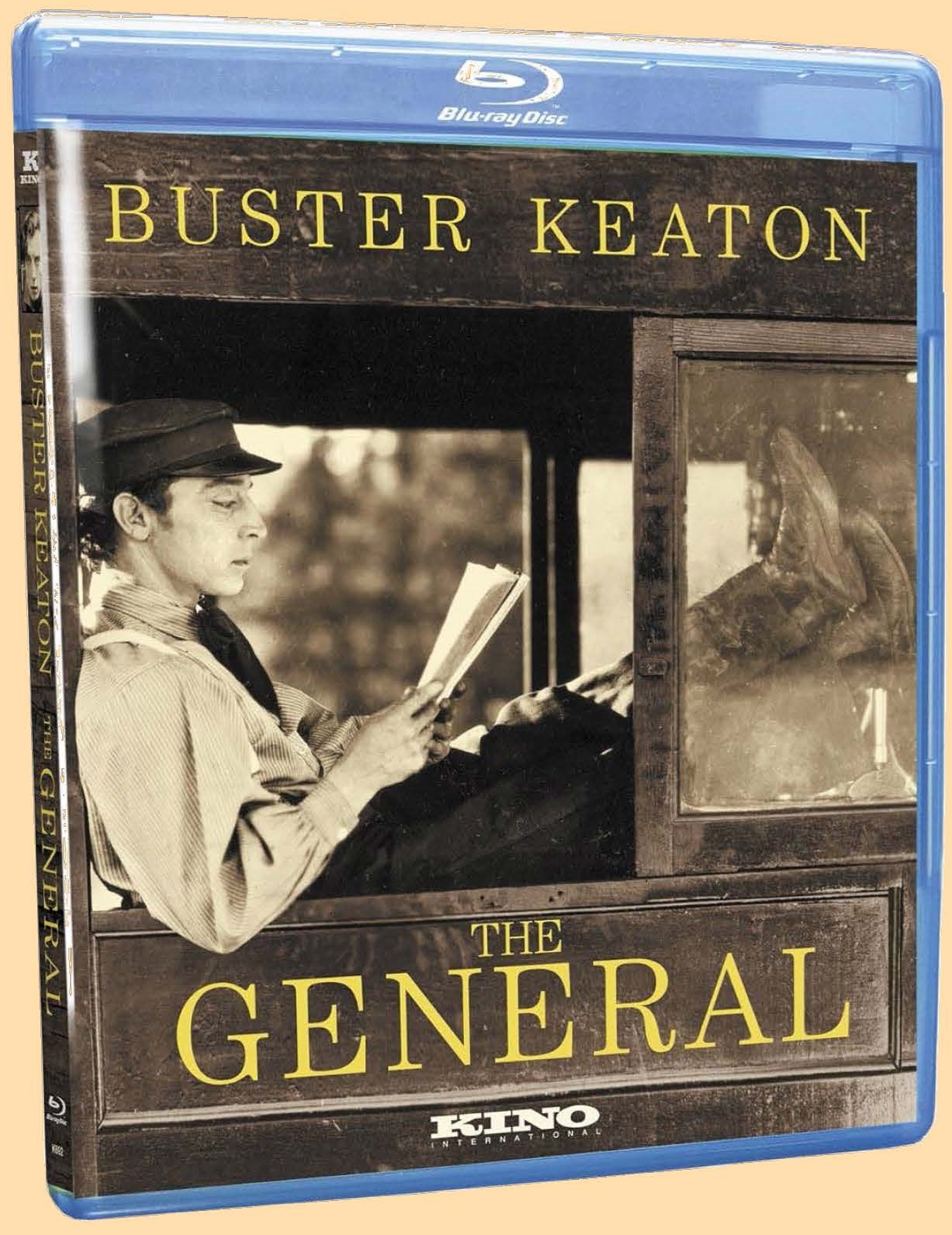

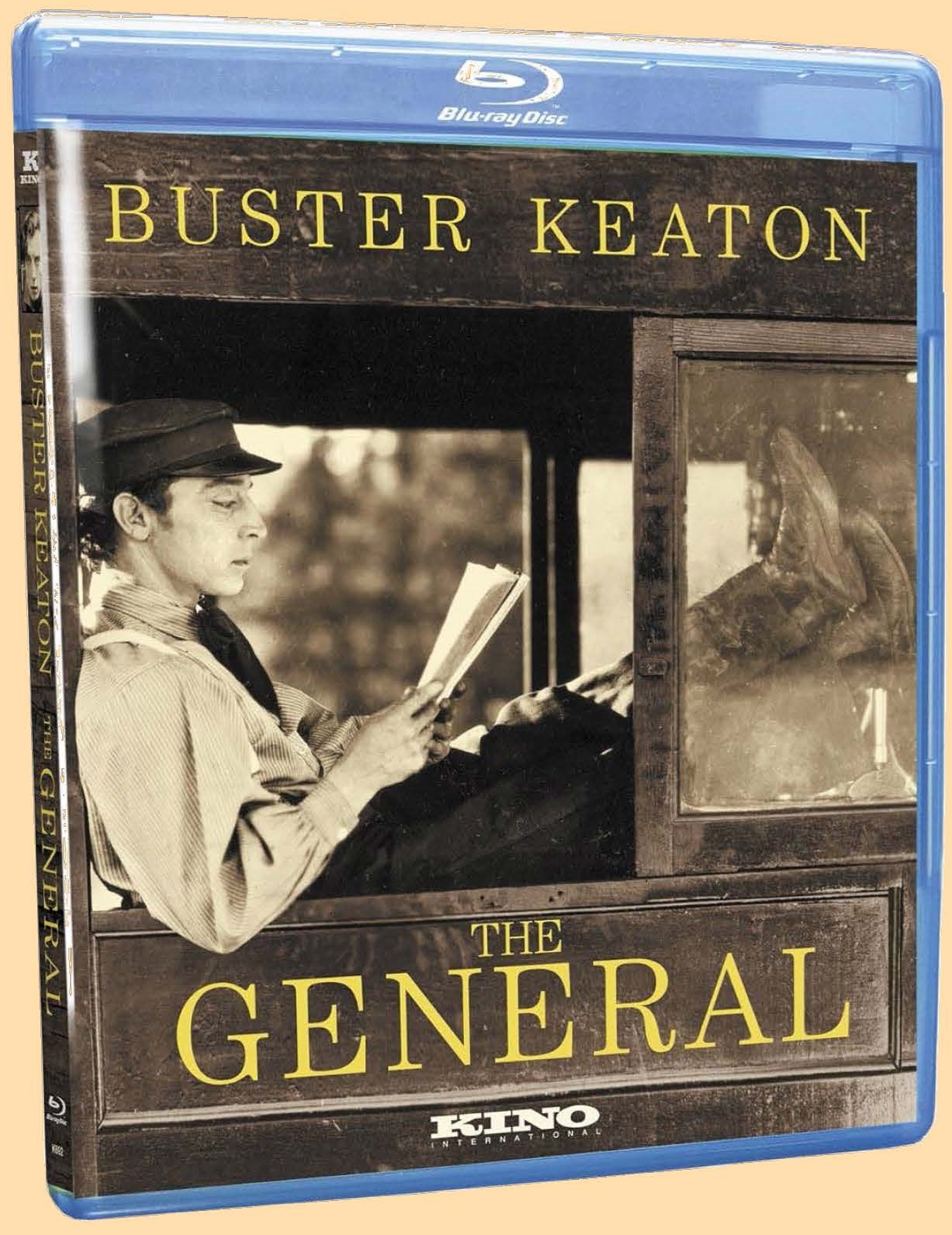

I checked the framing against the Kino K669 Blu-ray of November 10, 2009,

which is one of the very few editions that captured most of the image on the original film.

I discovered that the Showtime transmission included nearly the entire height of the image, which is surprising.

In the 1980’s, videos normally zoomed in and showed us only the center of the frame, losing all four sides.

This singular video transfer was a pleasant exception.

Alas, the left and right were missing, especially the left.

Why, I do not know.

I assume someone misaligned some video equipment somewhere along the process.

The height was 480p, and so, to simulate a .446" crop,

I lopped off 62p from the top and another 62p from the bottom,

so that I could finally witness what audiences saw in 1970 and 1971.

The result startled me, and you can see why.

The image does not fit the crop perfectly, but it fits almost perfectly, and that spooks me no end.

That simply does not happen with silent films of this vintage, it does not, it does not, it does not, EVER.

|