The Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) Revives Some Buster Keaton Movies |

|

I spent many months scratching my head, trying to make sense of this.

And when I finally thought I had the basics figured out,

Ed Watz, in an aside, proved me totally wrong.

So I tried it again, and then David Pierce made a post that demolished even my rewrite.

Let me try this yet again.

|

|

It was in 1933 that the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) founded its motion-picture library.

For the first two or three years, MoMA probably convinced the studios to sell release prints that were no longer needed.

That might be how MoMA acquired Go West.

For Our Hospitality, in 1940 MoMA acquired a freshly made nitrate print directly off of the negative.

That was probably all that MGM would agree to.

There had been duplicating films from Kodak going back to the

|

|

David Pierce informs us

that in 1935, MoMA asked if Harvard would be interested in donating its copies of those 13 movies.

Harvard agreed, and in 1936 those movies were on file at MoMA.

|

|

In

1941, to cater to the new private film clubs that were sprouting up all over the country,

MoMA made 16mm circulating prints of any films for which it had lavenders,

and that is how Sherlock Jr. and The Navigator were made available.

The General was also made available,

and that is why I conjectured above that at least one of each pair of positives at Harvard

must have been a lavender.

MoMA did not purchase any other Buster movies, for the simple reason that funds were limited (per Ed Watz).

My guess is that the studios agreed to share their intellectual property

only because those particular films were by then considered worthless.

The studios had zero intention of ever reissuing them.

|

|

MoMA probably made a single 35mm nitrate print of Sherlock Jr. and The Navigator for

|

|

I first saw Buster Keaton while I was five or six years old when my father took me to New York’s Museum of Modern Art,

where they often showed silent pictures.

My father had a nostalgic connection to these films

because he had grown up with them: when sound arrived, my father was 30 years old.

At MoMA, I was first introduced to Charlie Chaplin and D.W. Griffith,

but I remember that Buster got the biggest laughs of any of the silent comedians.

He was also the least sentimental....

|

|

All right. Peter was born on 30 July 1939, and so he was 5 or 6 in 1940/1941,

and bingo, the timeline fits!

|

|

The 16mm print of The General, by the way, appears to have been mounted onto

three 1,200 reels.

MoMA offered those 16mm prints to libraries and film clubs and other nonprofit organizations,

and untrained projectionists operating subpar machines

battered those prints.

Thus did a new generation discover Keaton and proclaim him a genius,

a description Buster sincerely rejected.

|

|

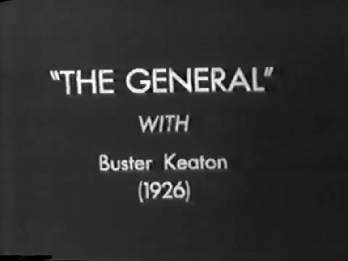

Here is how MoMA’s 16mm circulating prints opened:

|

This title replaced the original main title. |

|

By the time that the film societies were beginning to sprout, accompanists as a species were extinct.

As far as I can determine, film societies presented silent films dead silent, with no music at all.

MoMA, of course, had staff pianists who accompanied, among them Arthur Kleiner,

but MoMA was not a film society; it was a museum supported by the Rockefellers and the CIA.

Among film societies, though, I know of three admirable outliers

that appeared out of nowhere in later years.

Here is one:

|

|

|

Zo, what was that? That was certainly the 16mm MoMA print, double-sprocket silent.

The short films on the program were all, I’m pretty sure, in the MoMA rental catalogue.

What was this about “a sound track added”?

It must have been a homemade soundtrack on a reel-to-reel tape recorder,

with musical selections likely pulled from a music lover’s library of them thar newfangled LP vinyl discs.

Alternatively, and rather more likely, it could have been someone spinning discs.

It was definitely not an optical track on the actual film print; I’m absolutely certain of that.

|

|

And here is a screening at the Santa Rosa Junior College:

|