|

Sadly, I know next to nothing about this

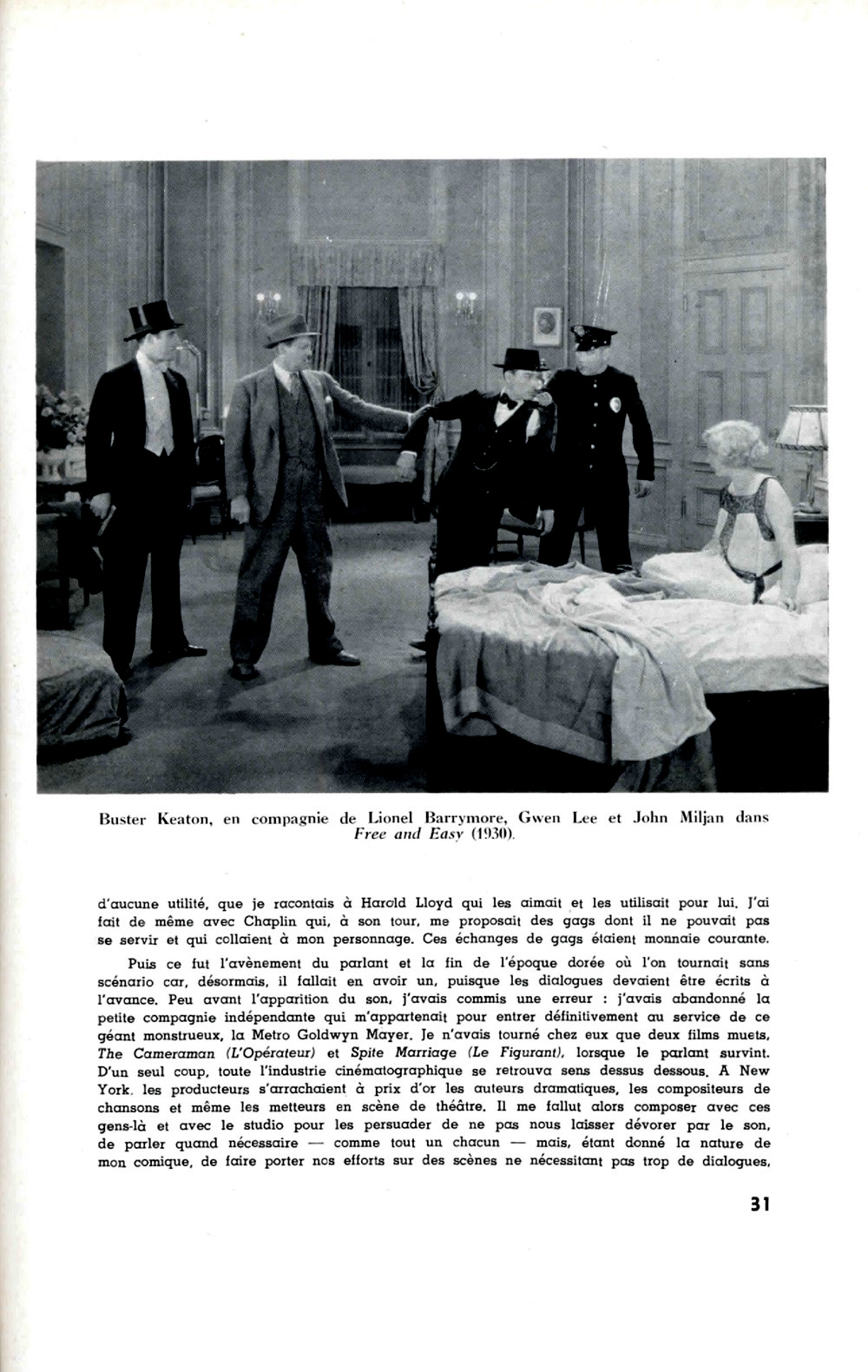

“Hommage à Buster Keaton.”

Are any of you in France?

Could you do us the kindness of checking the files at the Cinémathèque française

to learn the specifics, the schedule, the events, anything, everything?

Were these Cinémathèque prints or Rohauer prints, or a mixture of the two?

Henri Langlois was adamant about projecting silent films at 16fps and without any musical accompaniment.

Was that how Buster’s movies were shown (ruined?) during this retrospective?

Or did wiser heads prevail?

Does anybody know?

|

|

On the Cinémathèque’s website we have a paragraph by Laurent Mannoni,

“Langlois-Keaton in Paris,” Henri Langlois, 2024:

|

|

The work of the brilliant Buster Keaton has always been revered by the Cinémathèque since its founding,

and even before 1936, when Henri Langlois was already programming his film club, the Cercle du cinéma.

1962 was a very intense year for the Cinémathèque française.

“Tributes” multiplied

|

|

Above Laurent Mannoni’s paragraph we have a film by Freddy Baume, shot without sound,

showing, among other things, Buster at the Cinémathèque.

Only a few seconds at the end show Buster, with Henri Langlois and Raymond Rohauer.

Another tenuous link between my two favorite filmmakers:

Tinto Brass worked at the Cinémathèque at the time,

and so the two probably met, however briefly.

I isolated the few seconds with Buster:

|

|

|

|

On a page entitled “Langlois, le passeur,”

we learn that

Langlois’s wife, Mary Meerson, penned a memoir, in which she wrote:

|

|

Je regardais Keaton observer cette marée humaine.

Au bout d’un long moment, il s’est tourné vers moi et m’a demandé pourquoi ces gens étaient là.

Je lui ai répondu qu’ils étaient là pour lui, qu’ils étaient venus pour le voir.

J’ai vu alors dans ce visage impassible, austère, deux larmes perler et tomber doucement sur ses joues, sur son cou.

Finalement, étonné, émerveillé, reconnaissant, il a réussi à prononcer qualques phrases :

“ils sont si jeunes”

|

I watched Keaton observe this human tide.

After a long moment, he turned to me and asked why these people were there.

I replied that they were there for him, that they had come to see him.

Then I saw two tears in that impassive, austere face, falling softly down his cheeks and onto his neck.

Finally, astonished, amazed, grateful, he managed to utter a few sentences:

“They’re so young.”

|

|

On Archive.org, we see another little bit of film shot without sound:

|

|

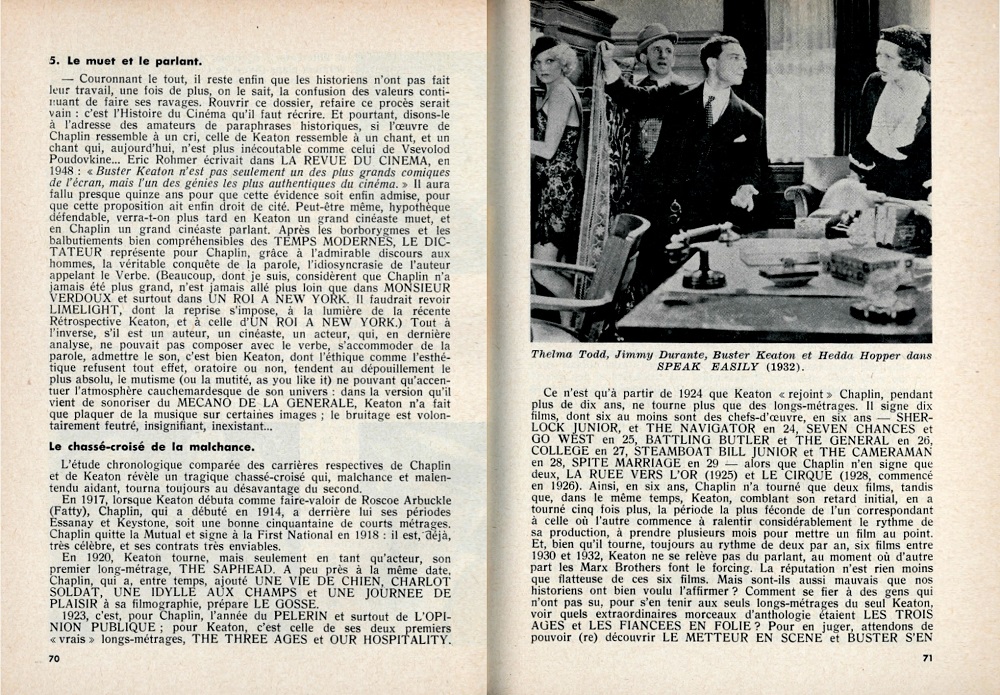

Buster Keaton In Paris 1962 Is that Lotte Eisner we glimpse right at the end? Another tenuous link: She was Tinto’s mentress. |

|

Apparently there is yet another film, on file at the Cinémathèque:

Mario Beunat,

Buster Keaton à la Cinémathèque française, 2 minutes.

Is that what we see below? I do not know.

|

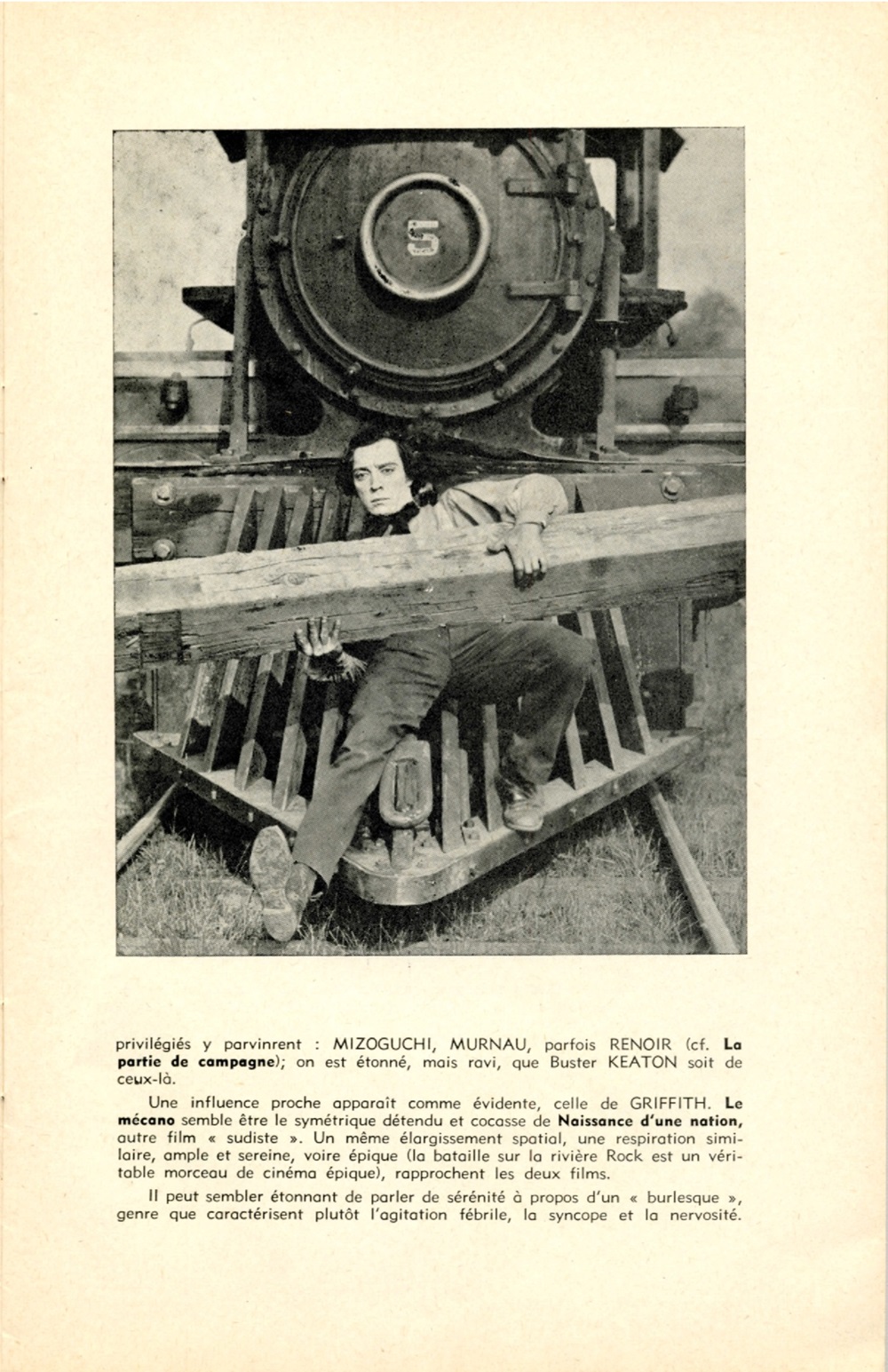

orsons, Paris, February 1962: Buster Keaton examines the first film projector made by the Lumière brothers at the Cinémathèque Française. |

|

US film director and actor Buster Keaton listens to film director...

US film director and actor Buster Keaton listens to film director Abel Gance, on February 23 in Paris

where he came to present a new version of his film “The General”, directed on 1926.

|

|

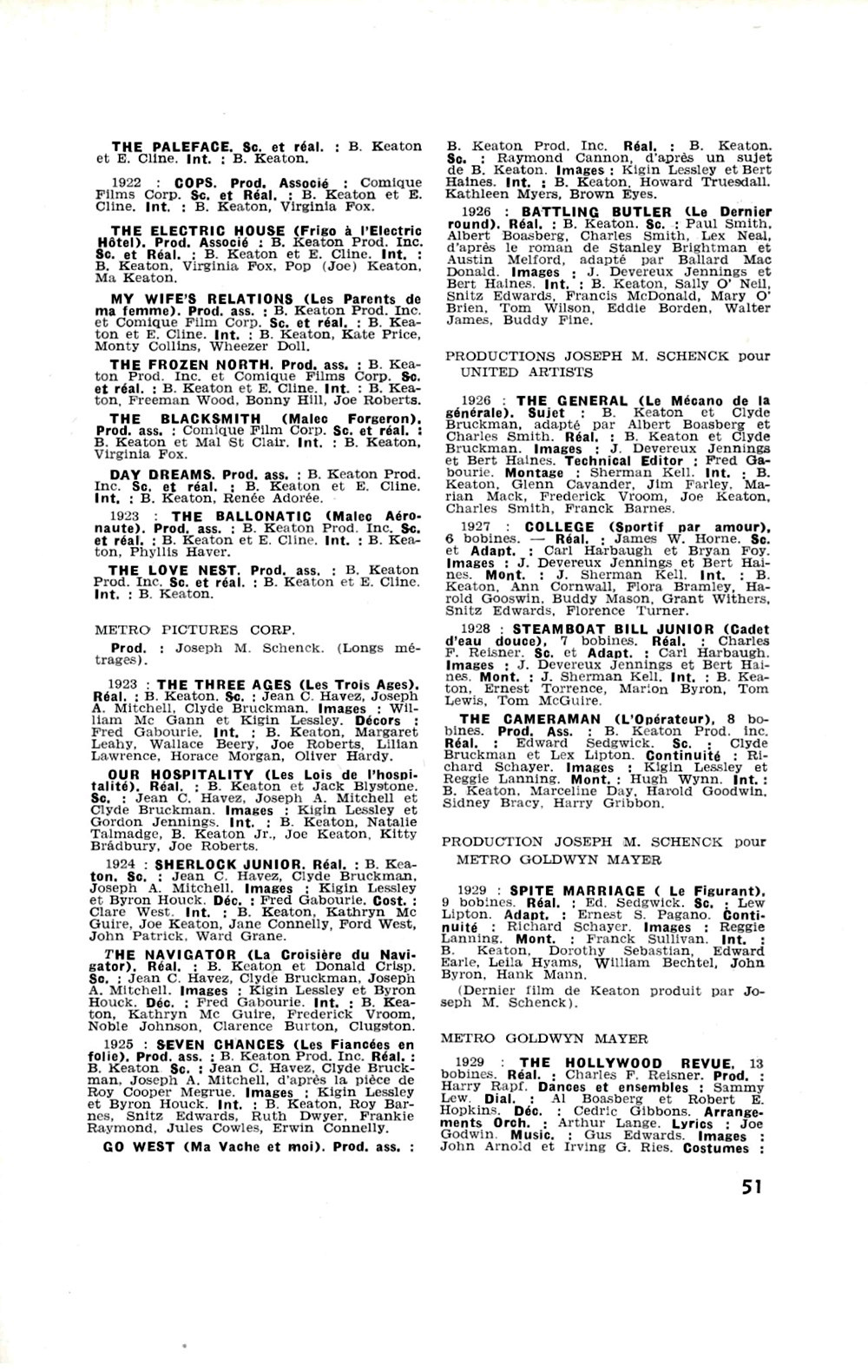

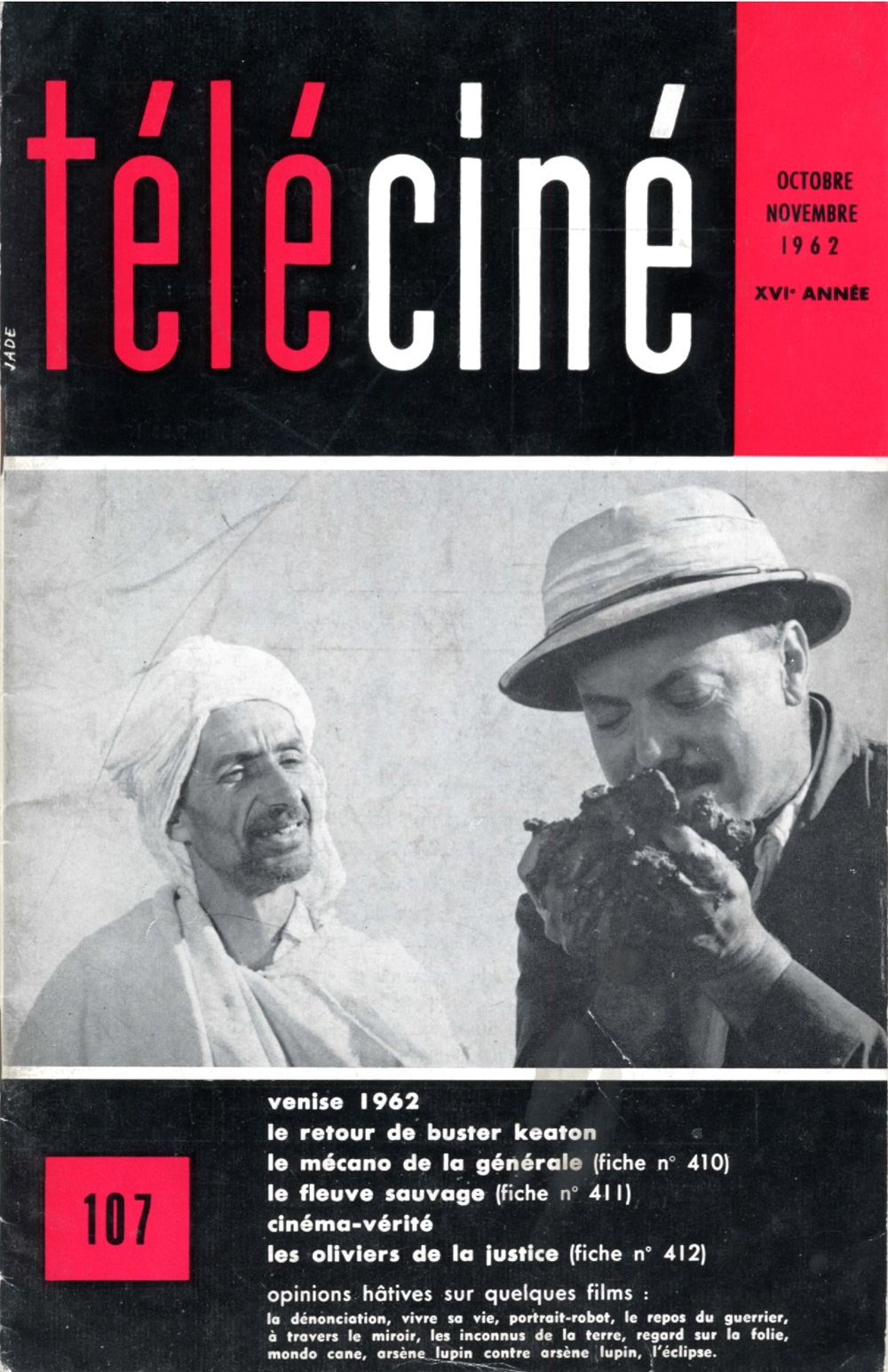

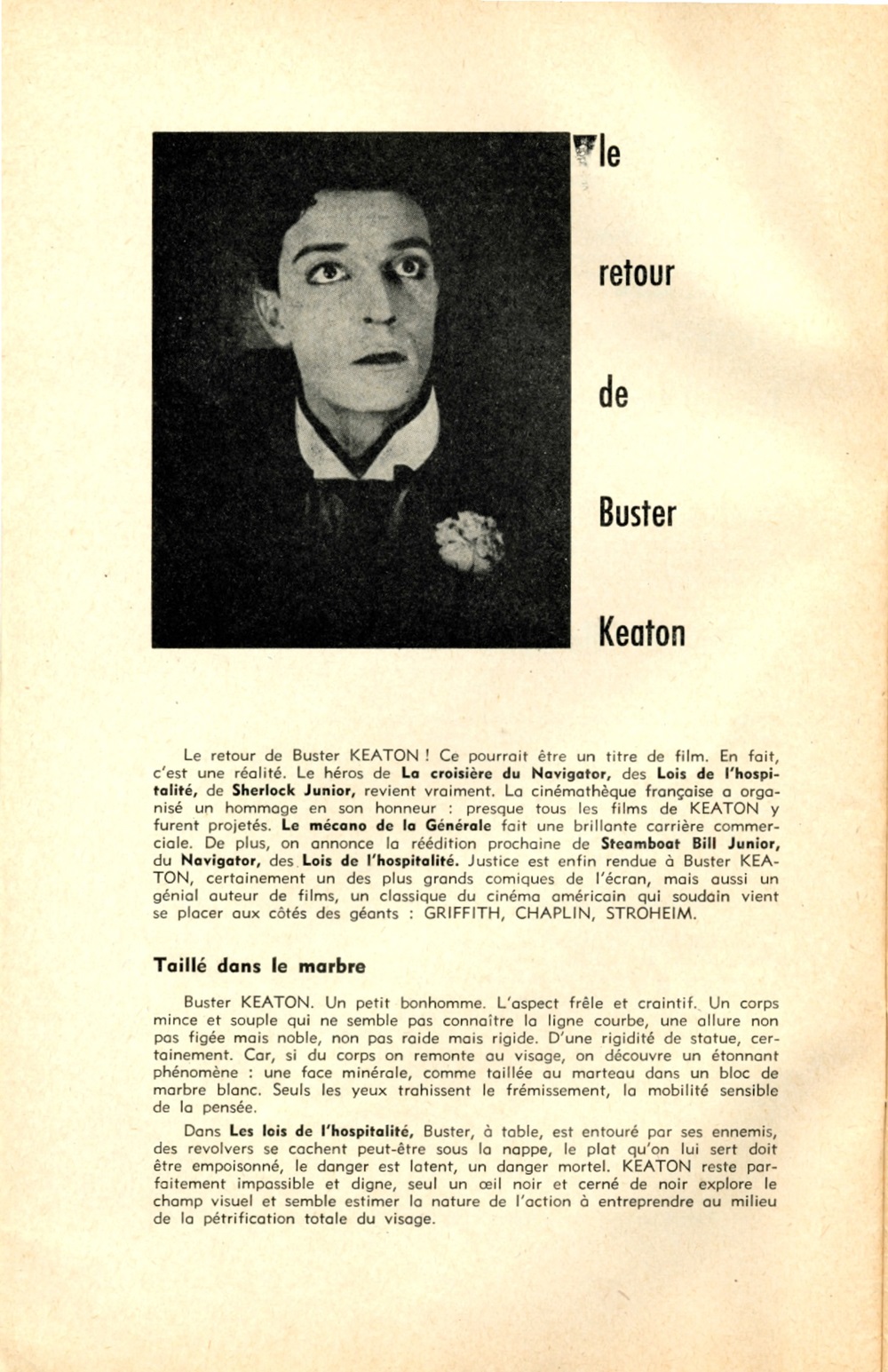

In the vague hope that I might be able to learn what precisely was shown at this retrospective, and when, and how,

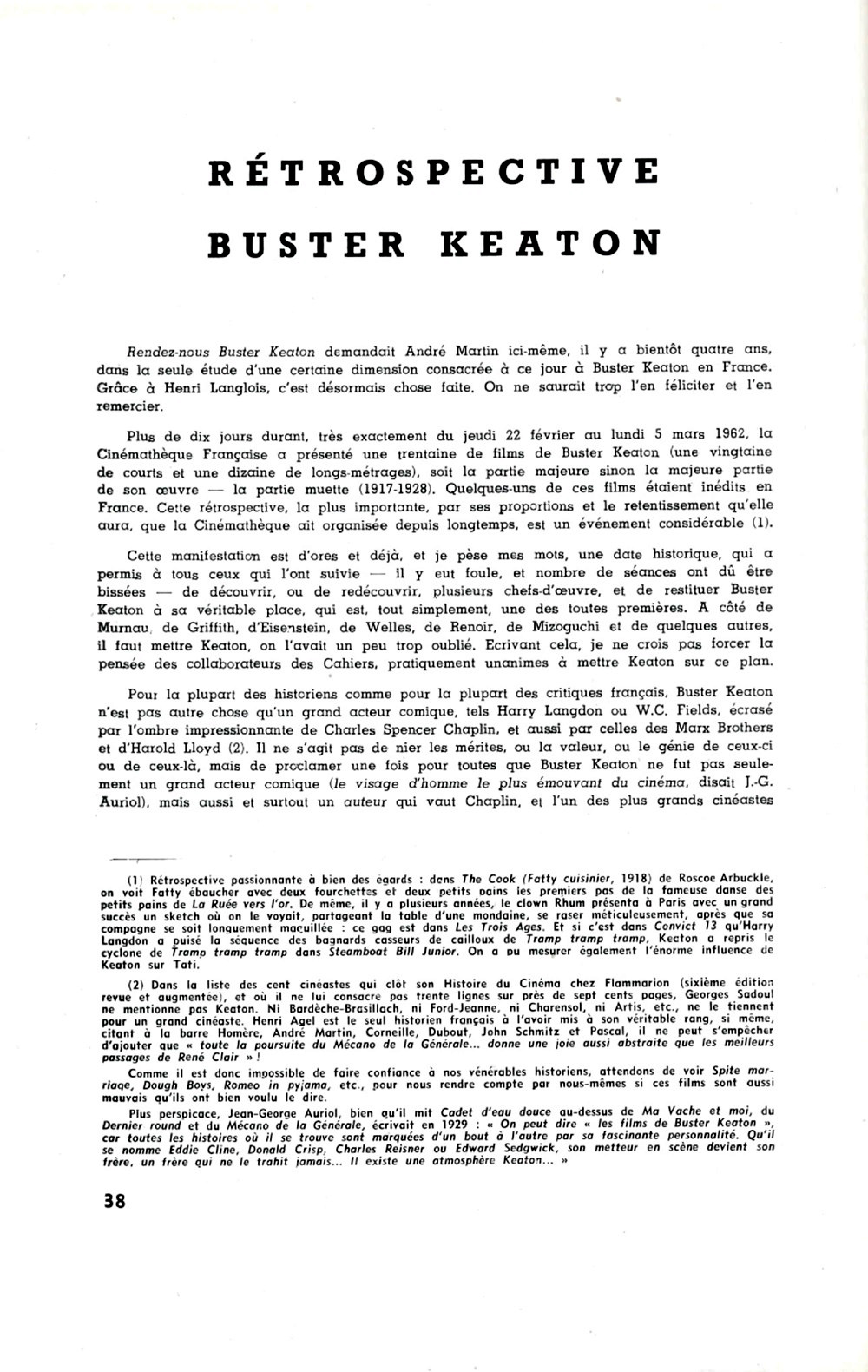

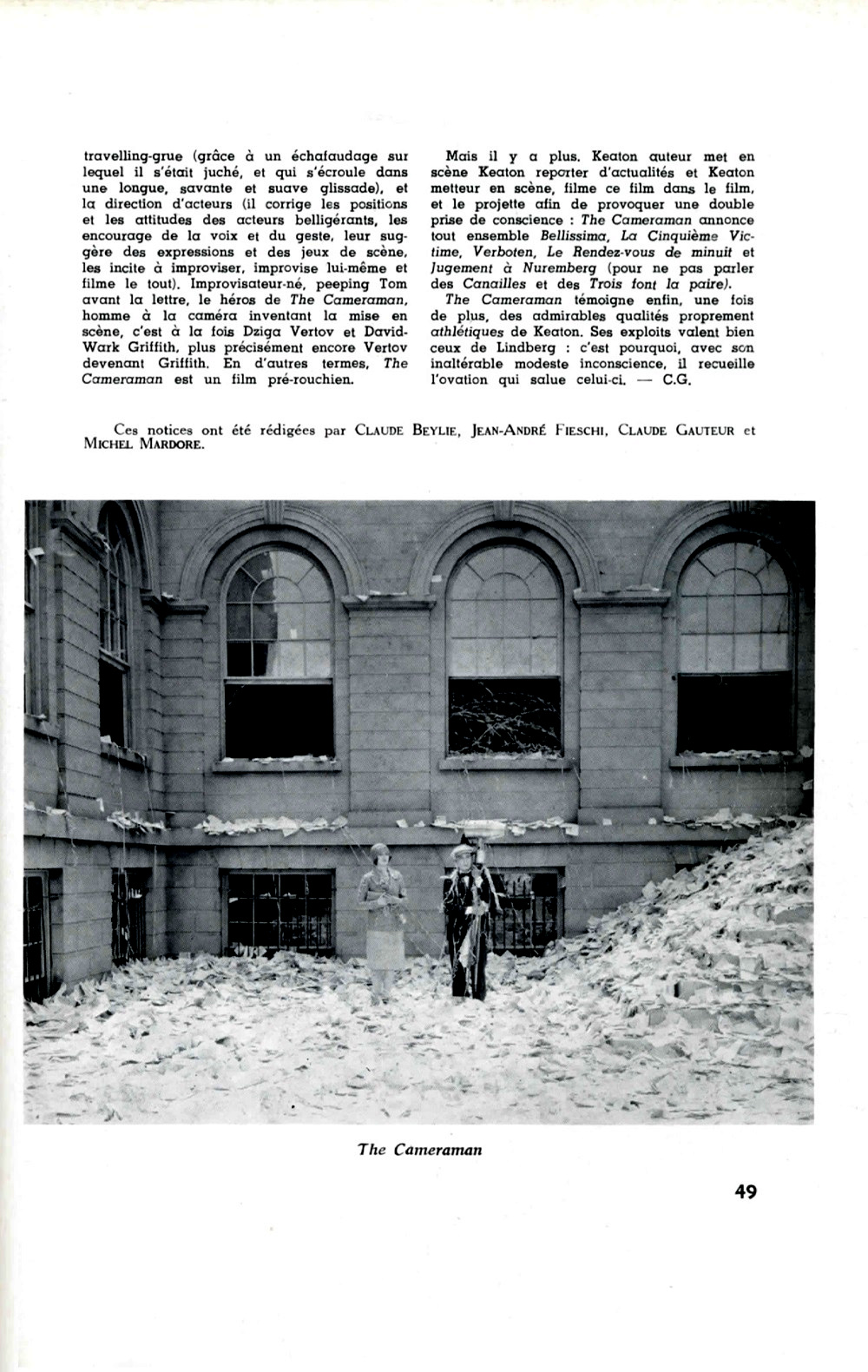

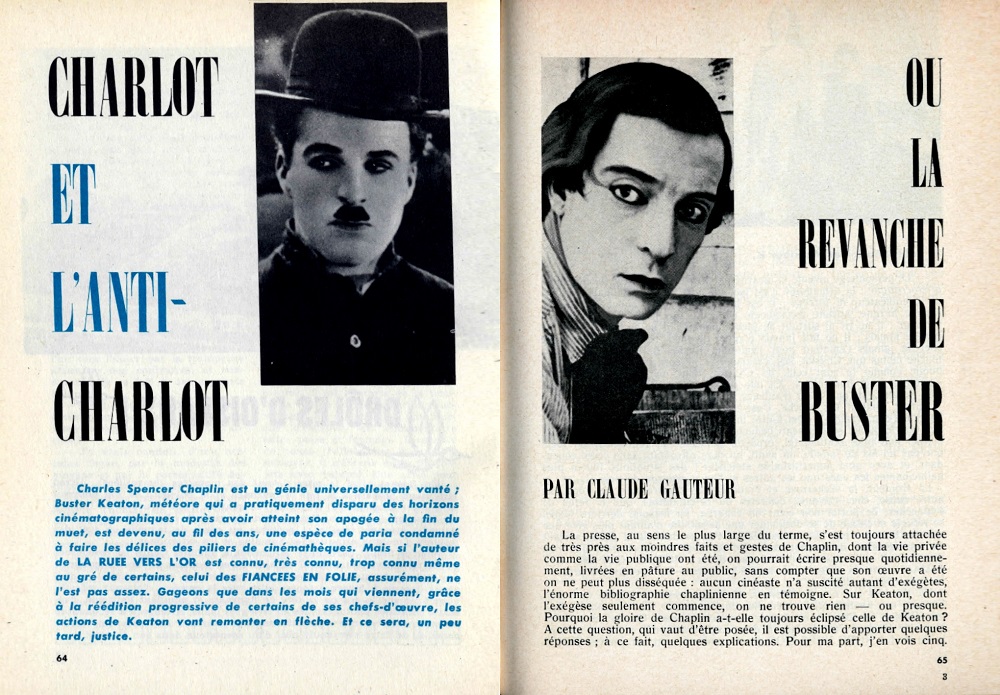

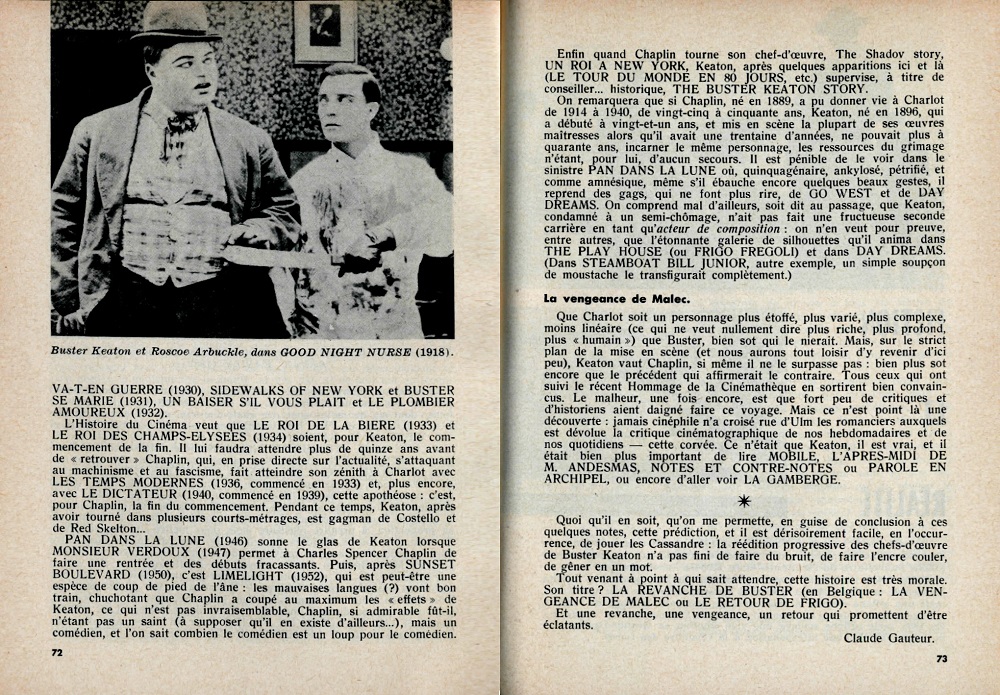

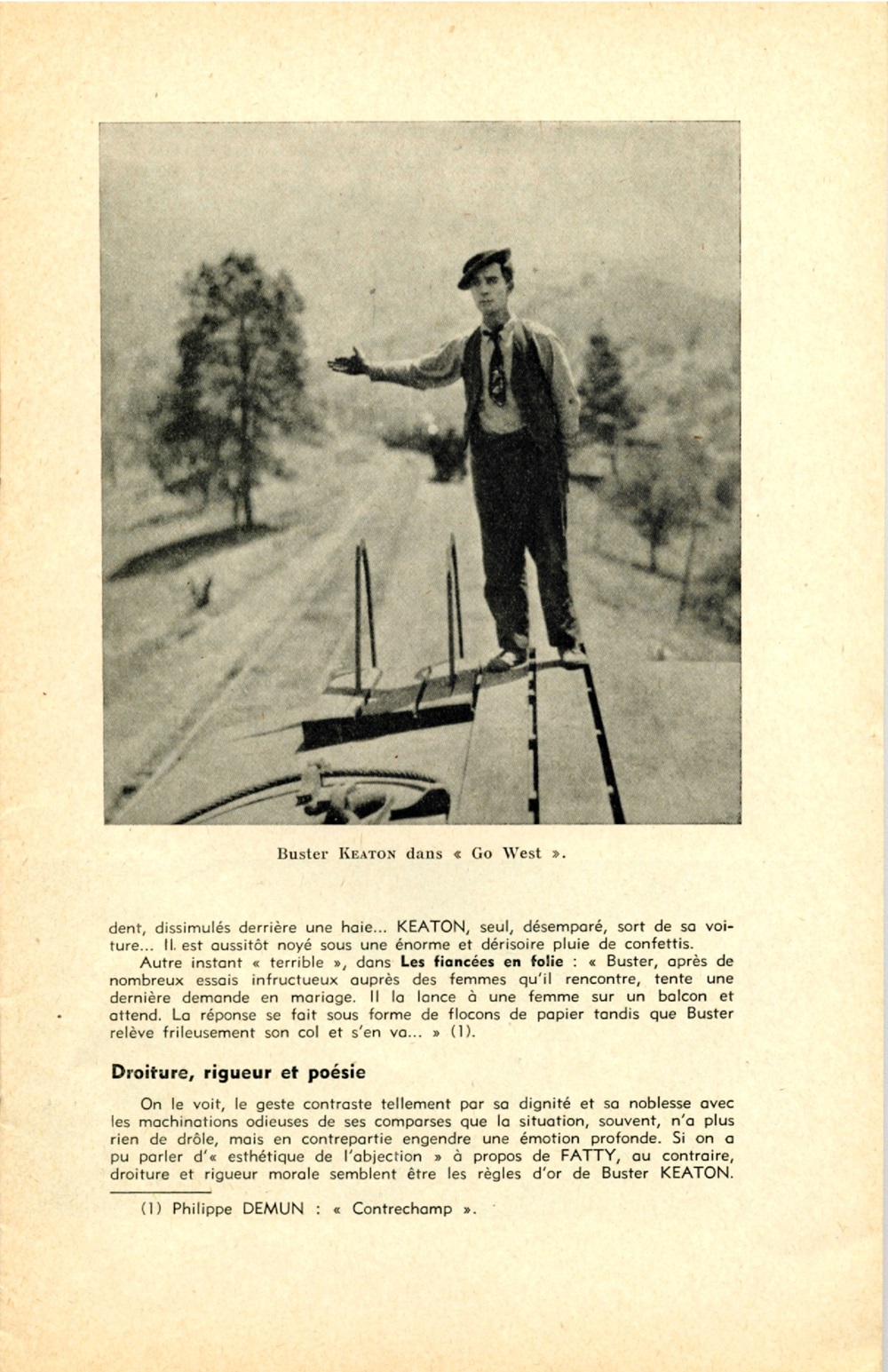

I looked at Claude Miller’s article in téléciné, October/November 1962.

Unfortunately, the article is an editorial about Buster’s brilliance;

it is not a record about the specifics.

Nonetheless, there might be a clue.

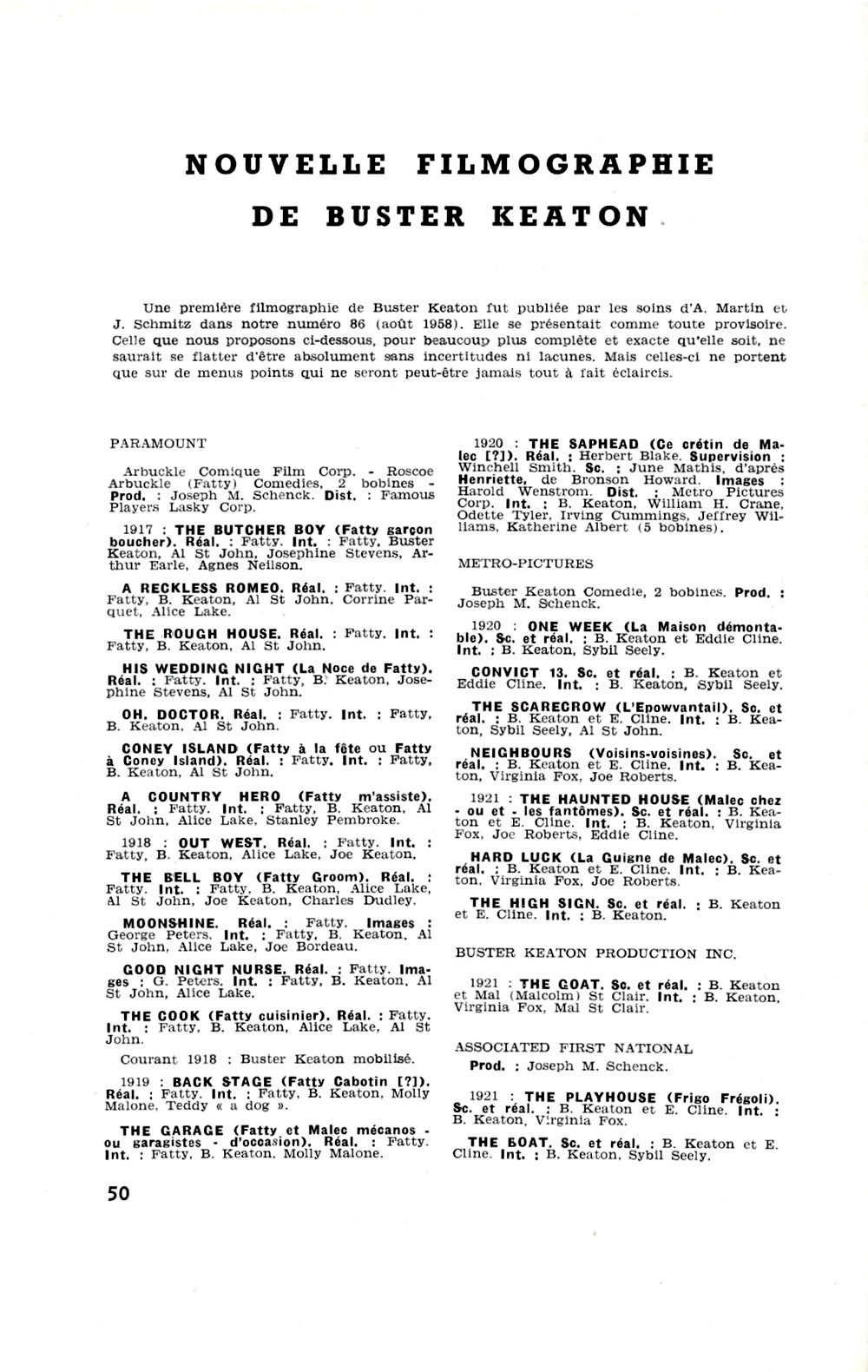

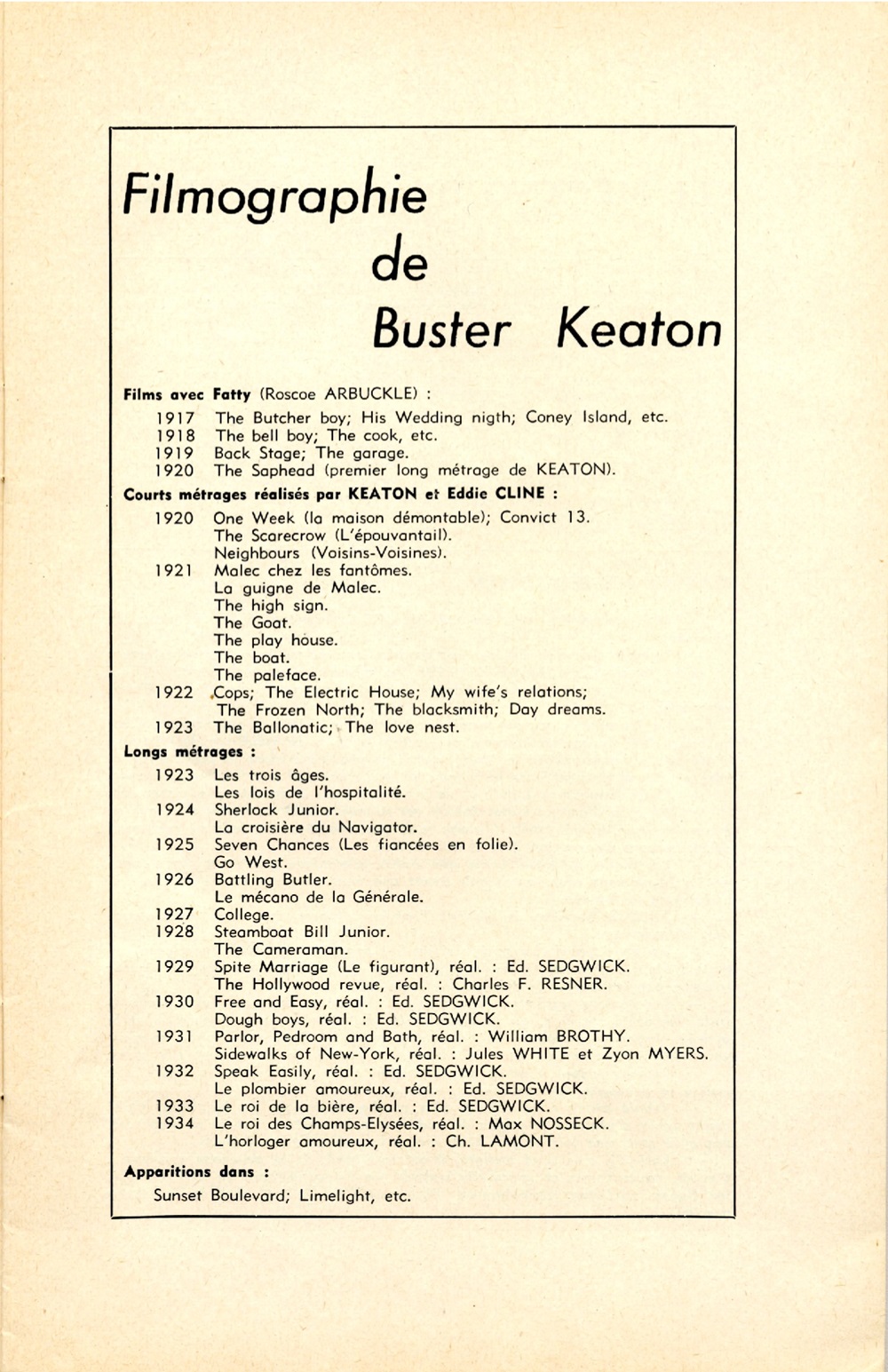

It concludes with a “Filmographie de Buster Keaton,”

which includes the bulk of his silents, including films that were considered lost at the time.

It takes his work through MGM and Le roi des Champs-Élysées,

after which it jumps ahead to Sunset Boulevard and Limelight,

and that was it.

So I suppose that those were pretty much the movies that were shown,

minus the missing ones, of course.

Buster was not around to attend this retrospective.

He put in his one brief appearance ahead of time, and then he was off for other chores.

I wonder what he would have thought about 16fps minus accompaniment.

Methinks he would have been heartsick.

|

|

Oh goodness gracious! It just now occurs to me.

That little pamphlet that is sitting on my shelf.

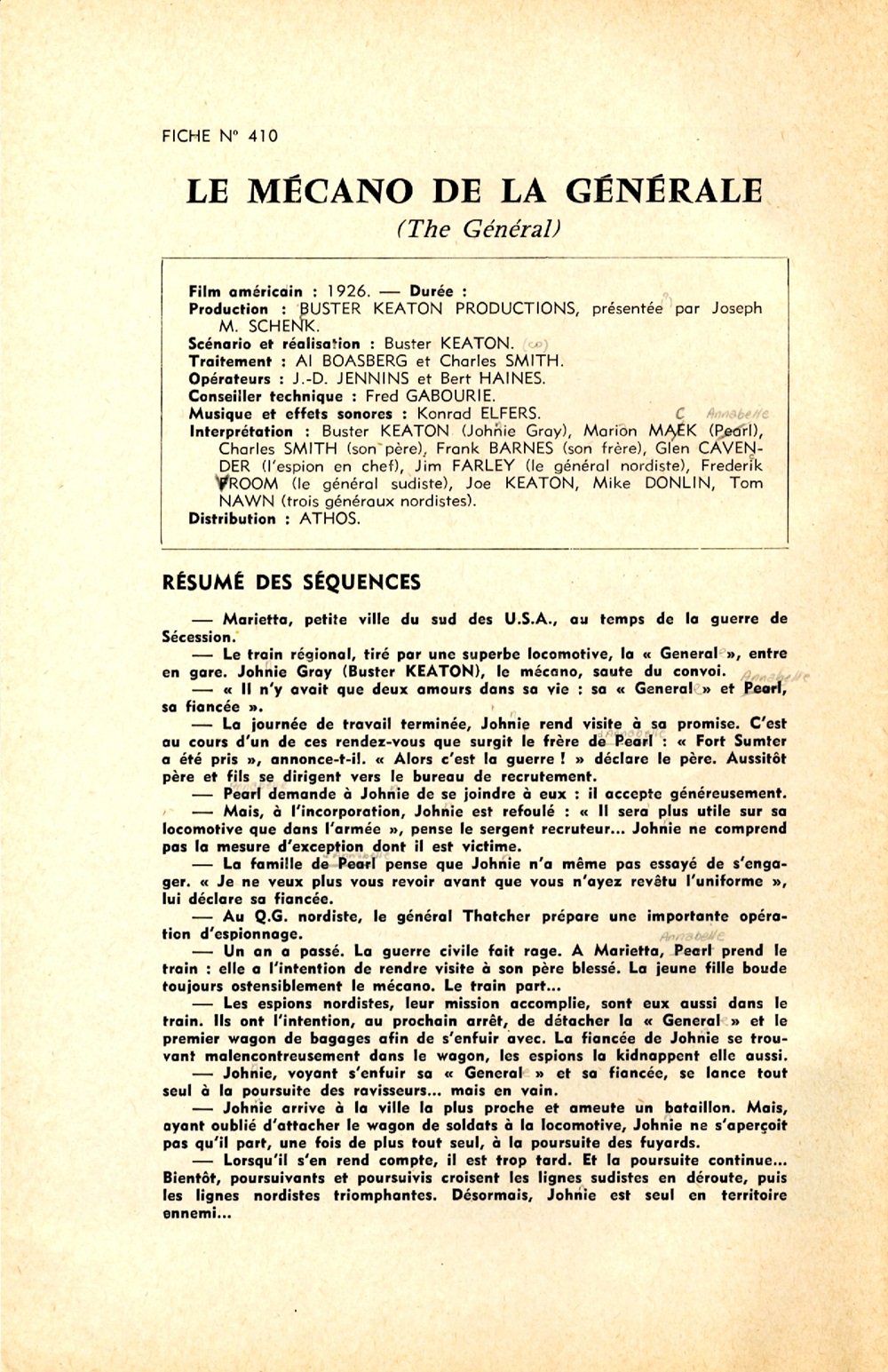

Yes. Marcel Oms, Buster Keaton, No. 31 of the series “Premier Plan,”

published in January 1964 by SERDOC,

Société d’ Études, Recherches et Documentation Cinématographiques

(28, rue Villeroy, Lyon (3)),

was an outgrowth of the February/March 1962 Hommage.

|

|

|

It is difficult for me to interpret the above article, especially since I do not speak French.

Nonetheless, let’s see what we can do.

Some of Buster’s movies are named in French and some are named in English.

That’s a clue.

We can turn to the volume by the two Georges, Wead and Lellis,

The Film Career of Buster Keaton (Boston: G.K. Hall & Co., 1977),

which supplies the French and Italian names of the movies,

but there was a problem.

The two Georges did not have full information.

For some gaps we can turn to Marcel Oms’s pamphlet.

Some films had multiple names, and I suppose that one was for the original release

and another was for a reissue, perhaps in the 1960’s, or for a proposed reissue.

With this minimal information, we can perform a preliminary investigation.

Let us draw out a chart consisting of

the original English name,

the French name or names,

and the way that Claude Miller refers to each movie in his “Rétrospective Buster Keaton” above.

My guess is that if Miller did not know the French title, then it was Rohauer who supplied that particular print,

if, indeed, the film was shown at all, which is uncertain.

The same applies when Miller indicates that a film’s name is not firmly established in the record.

Several of these films at the time were considered lost:

The Rough House;

Oh! Doctor;

His Wedding Night;

A Country Hero (still presumed lost);

Out West;

The Bell Boy;

Moonshine;

Good Night, Nurse;

The Cook;

Back Stage;

The Hayseed;

The Garage;

Hard Luck; and

The Love Nest.

Three Ages had to have been a Rohauer dupe, because nothing else was available.

|

|

Now, let us turn to the booklet that accompanied “The Masters of Cinema” (#150)

|

| PRESUMED SUPPLIER |

ENGLISH | FRENCH | CAHIERS |

| — | The Butcher Boy | Fatty boucher Fatty garçon boucher |

Fatty garçon boucher |

| — | The Rough House | Fatty chez lui | The Cook |

| — | Oh! Doctor | Fatty docteur | — |

| — | His Wedding Night | La noce de Fatty | La noce de Fatty |

| — | Fatty at Coney Island | Fatty à la fête Fatty à Coney Island |

Fatty à la fête Fatty à Coney Island |

| — | A County Hero | Fatty m’ assiste | Fatty m’ assiste |

| — | Out West | Fatty bistro | Out West |

| — | The Bell Boy | Fatty groom | Fatty groom |

| — | Moonshine | La mission de Fatty | Moonshine |

| — | Good Night, Nurse (misidentified as Oh! Doctor) |

Fatty à la clinique | Oh, Doctor |

| — | The Cook | Fatty cuisinier | Fatty cuisinier |

| — | Back Stage | Fatty cabotin | Fatty cabotin[?] |

| — | The Hayseed | Fatty au village | — |

| — | The Garage | Fatty et Malec mécanos ou garagistes d’ occasion Le garage de Fatty Un garagiste à la hauteur |

Fatty et Malec mécanos — ou garagistes — d’ occasion |

| Cinémathèque | One Week | Le maison démontable | Le maison démontable |

| Rohauer | The Saphead | Ce crétin de Malec | Ce crétin de Malec[?] |

| Rohauer | Convict 13 | Malec champion de golf | Convict 13 |

| Cinémathèque | The Scarecrow | L’ epouvantail | L’ epowvantail |

| Cinémathèque | Neighbors | Voisins-voisines | Voisins-voisines |

| Rohauer | The Haunted House | Malec chez les fantômes | Malec chez — ou et — les fantômes |

| — | Hard Luck | La guigne de Malec | La guigne de Malec |

| Rohauer | The High Sign | Malec champion de tir | The High Sign |

| Rohauer | The Goat | L’ insaisissable | The Goat |

| Cinémathèque | The Play House | Frigo fregoli | Frigo frégoli |

| Rohauer | The Boat | Frigo capitaine au long cours | The Boat |

| Rohauer | The Paleface | Malec chez les indiens | The Paleface |

| Rohauer | Cops | Frigo déménageur Les flics |

Cops |

| Cinémathèque | My Wife’s Relations | Les parents de ma femme | Les parents de ma femme |

| Cinémathèque | The Blacksmith | Malec forgeron | Malec forgeron |

| Rohauer | The Frozen North | Frigo esquimau | The Frozen North |

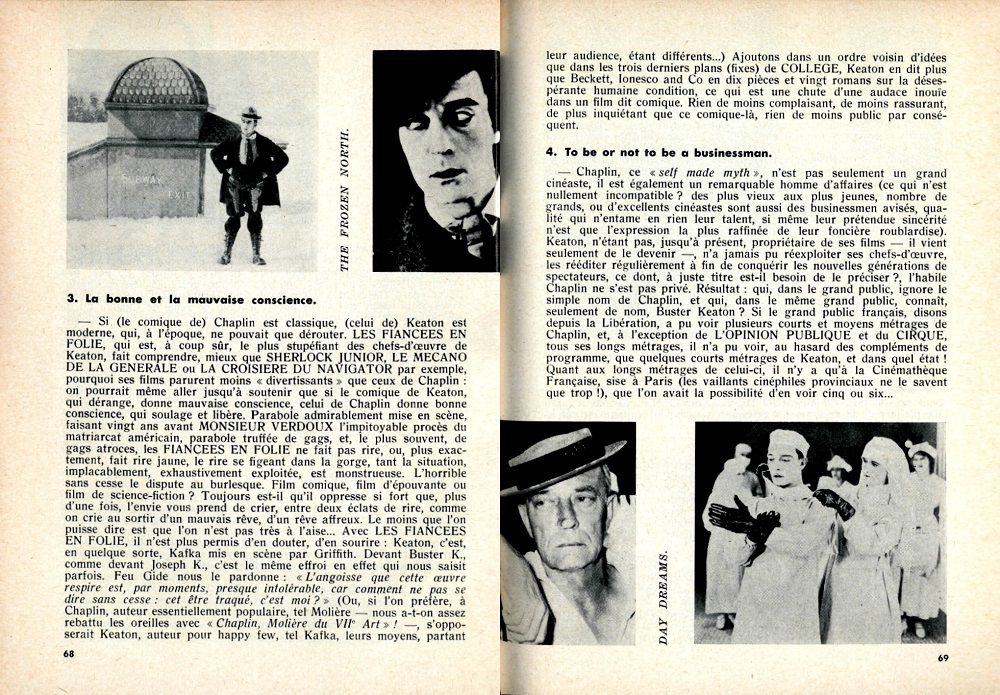

| Rohauer | Day Dreams | Grandeur et décadence | Day Dreams |

| Cinémathèque | The Electric House | Frigo e l’ électric hôtel | Frigo à l’ électric hôtel |

| Cinémathèque | The Balloonatic | Malec aéronaute | Malec aéronaute |

| — | The Love Nest | Frigo et la baleine Le nid d’ amour |

The Love Nest |

| Rohauer | Three Ages | Les trois ages | Les trois ages |

| Cinémathèque | Our Hospitality | Les lois de l’ hospitalité | Les lois de l’ hospitalité |

| Cinémathèque | Sherlock Jr. | Sherlock junior détective | Sherlock Junior |

| Cinémathèque | The Navigator | La croisière du « Navigator » | La croisière du Navigator |

| Cinémathèque | Seven Chances | Les fiancées en folie | Les fiancées en folie |

| Cinémathèque | Go West | Ma vache et moi | Ma vache et moi |

| Cinémathèque | Battling Butler | Le dernier round | Le dernier round |

| Cinémathèque | The General | Le mécano de la « Générale » | Le mécano de la générale |

| Cinémathèque | College | Sportif par amour | Sportif par amour |

| Cinémathèque | Steamboat Bill, Jr. | Cadet d’ eau douce | Cadet d’ eau douce |

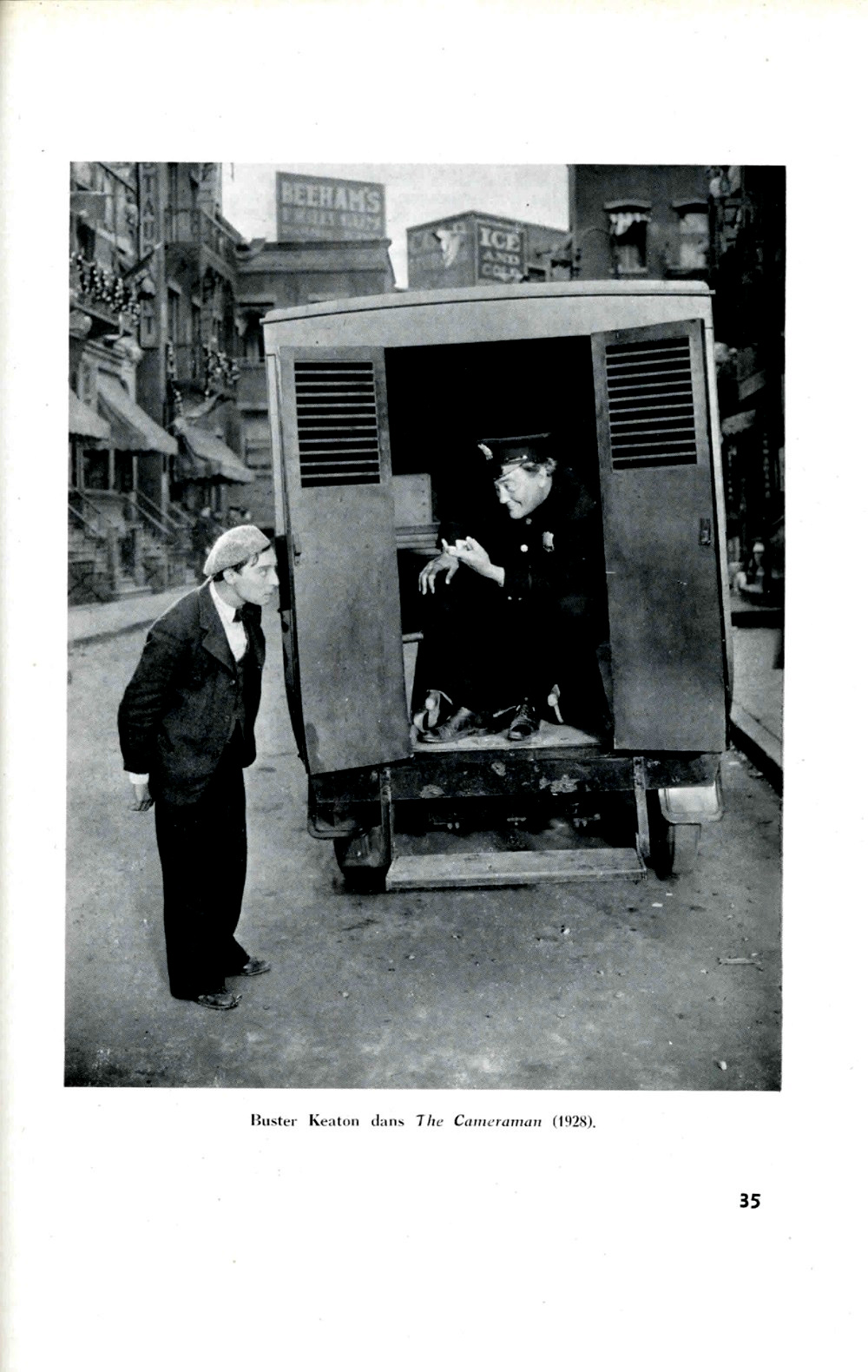

| Cinémathèque | The Cameraman | L’ opérateur | The Cameraman |

|

So, we can tentatively conclude that some of the prints shown at the retrospective

were French nitrates left over from the 1920’s and deposited at the Cinémathèque,

and that some were 16mm diacetate dupes supplied by Ray Rohauer.

The one grand mystery is The Cameraman.

Where on earth did that print come from?

My best guess is that it was part of the Cinémathèque Française collection

and that it was a Belgian print with English titles but with French and Flemish translations,

and that this was the same print that the BFI had presented in November 1959 at the National Film Theatre in London.

What’s more, I’ll go out on a limb and state that it is probably still at the Cinémathèque Française

but that it is in mislabeled cans or that it has been wrongly catalogued and indexed.

I bet it’s still there, and I bet nobody knows.

And I bet nobody has even bothered to look.

|

|

|