The Red Mole

There are few fond memories in this noggin of mine,

but most of the few fondest memories are of a group of people I never got to know.

It was in late 1979 that my friend John Hoffsis asked if I had heard of something called the Red Mole.

No, I hadn’t. What was it?

It was a group of itinerant performers who were busking in the Old Town Plaza, where he worked, making a racket all day long, day after day.

I remarked instantly that this sounded perfectly dreadful.

I had no interested in knowing more.

Then a few days later I entered the auditorium of the Rodey Theatre on the UNM campus for John Malolepsy’s lighting class,

but I was a minute or two early, and the previous class was still in session, with everyone in thrall to the three people being interviewed on stage:

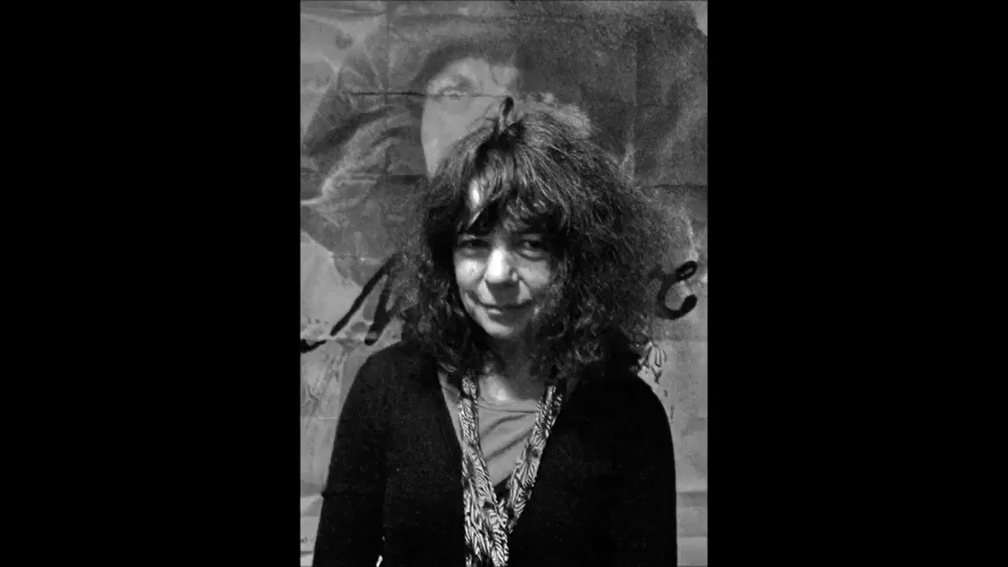

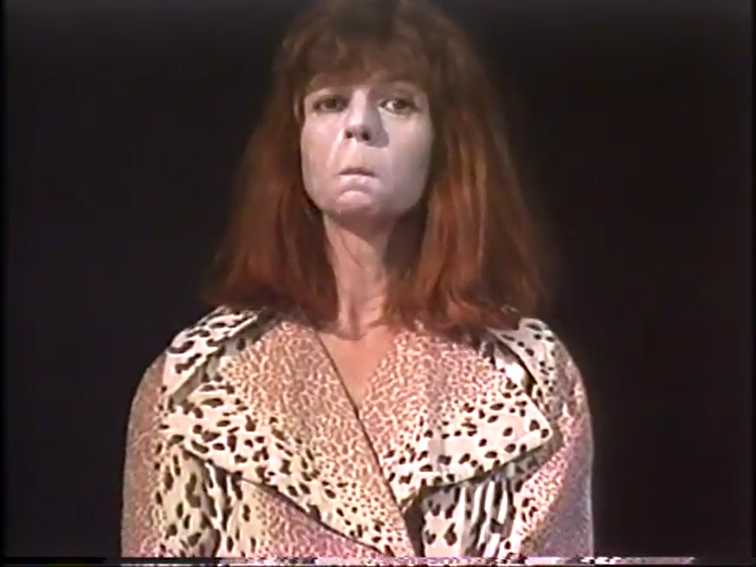

Alan Brunton, his wife Sally Rodwell (who spoke not a word), and the eloquent Deborah Hunt.

From those two minutes or so, I concluded that Alan, Sally, and Deborah were the most brilliant people I had ever seen.

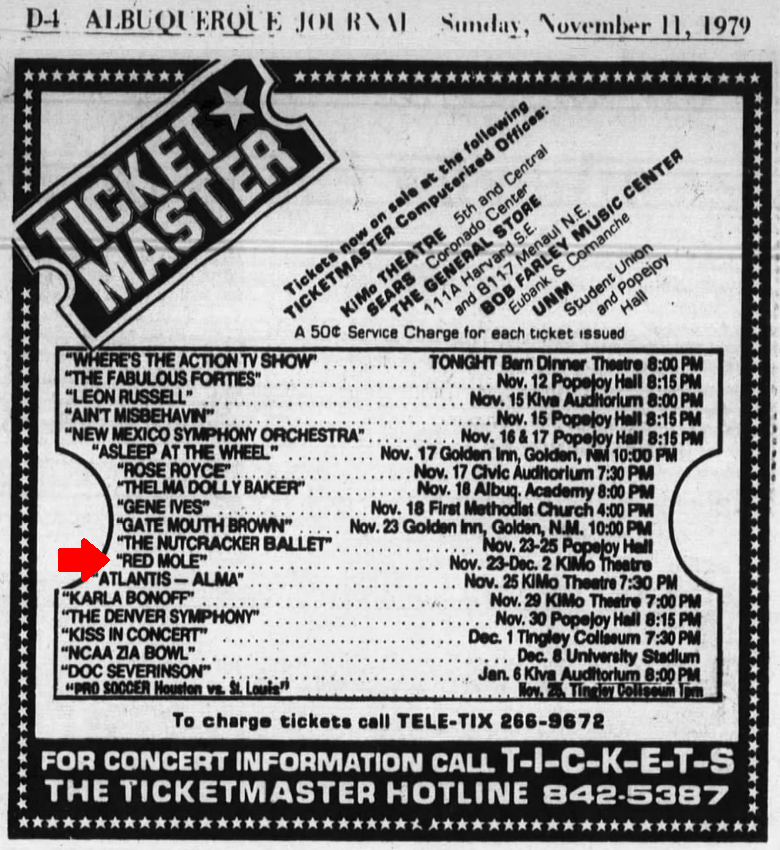

I never saw the below newspaper items until just now:

Albuquerque Journal vol. 98 no. 315, Sunday, 11 November 1979, p. B-4

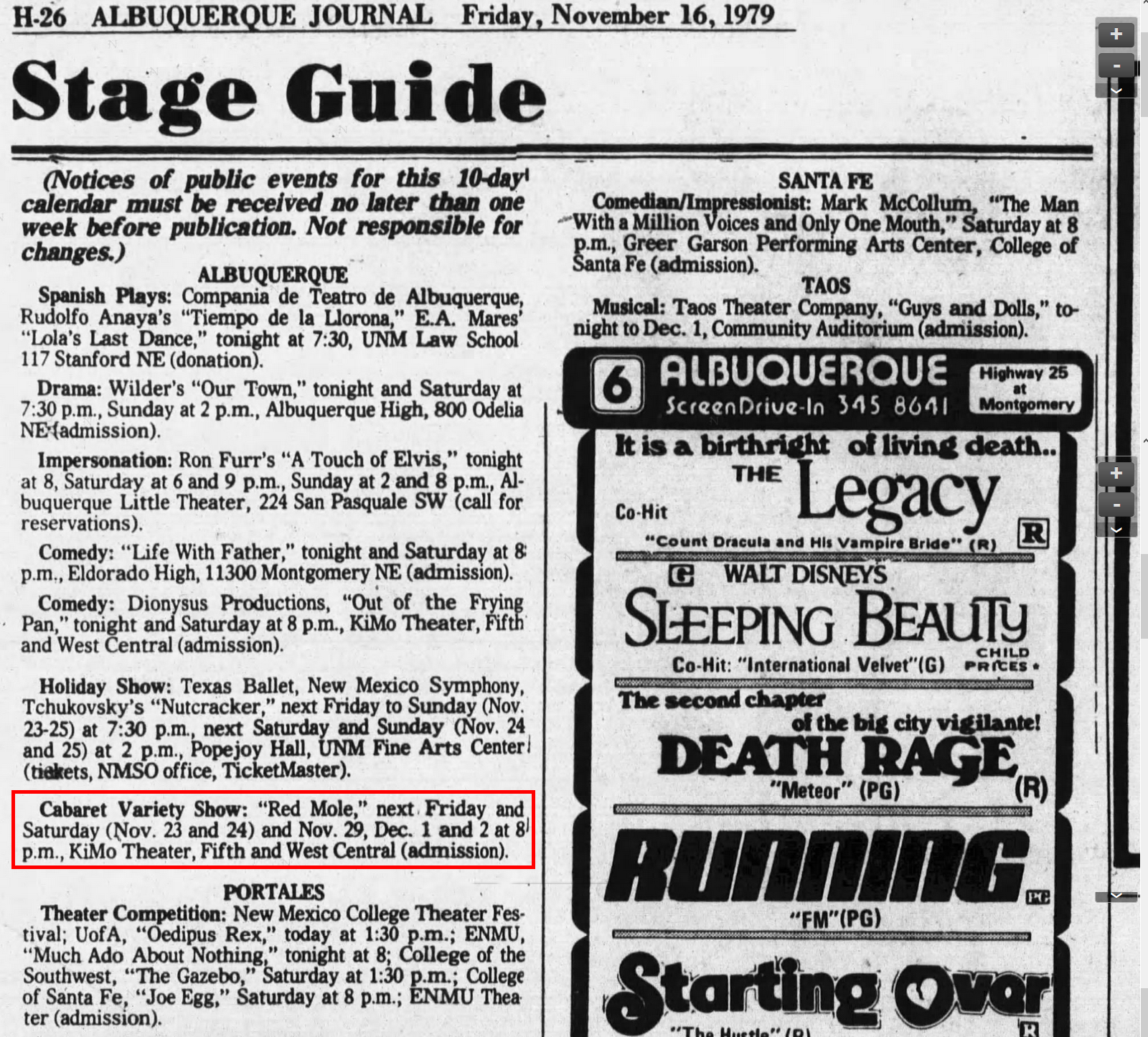

Albuquerque Journal vol. 98 no. 320, Friday, 16 November 1979, p.

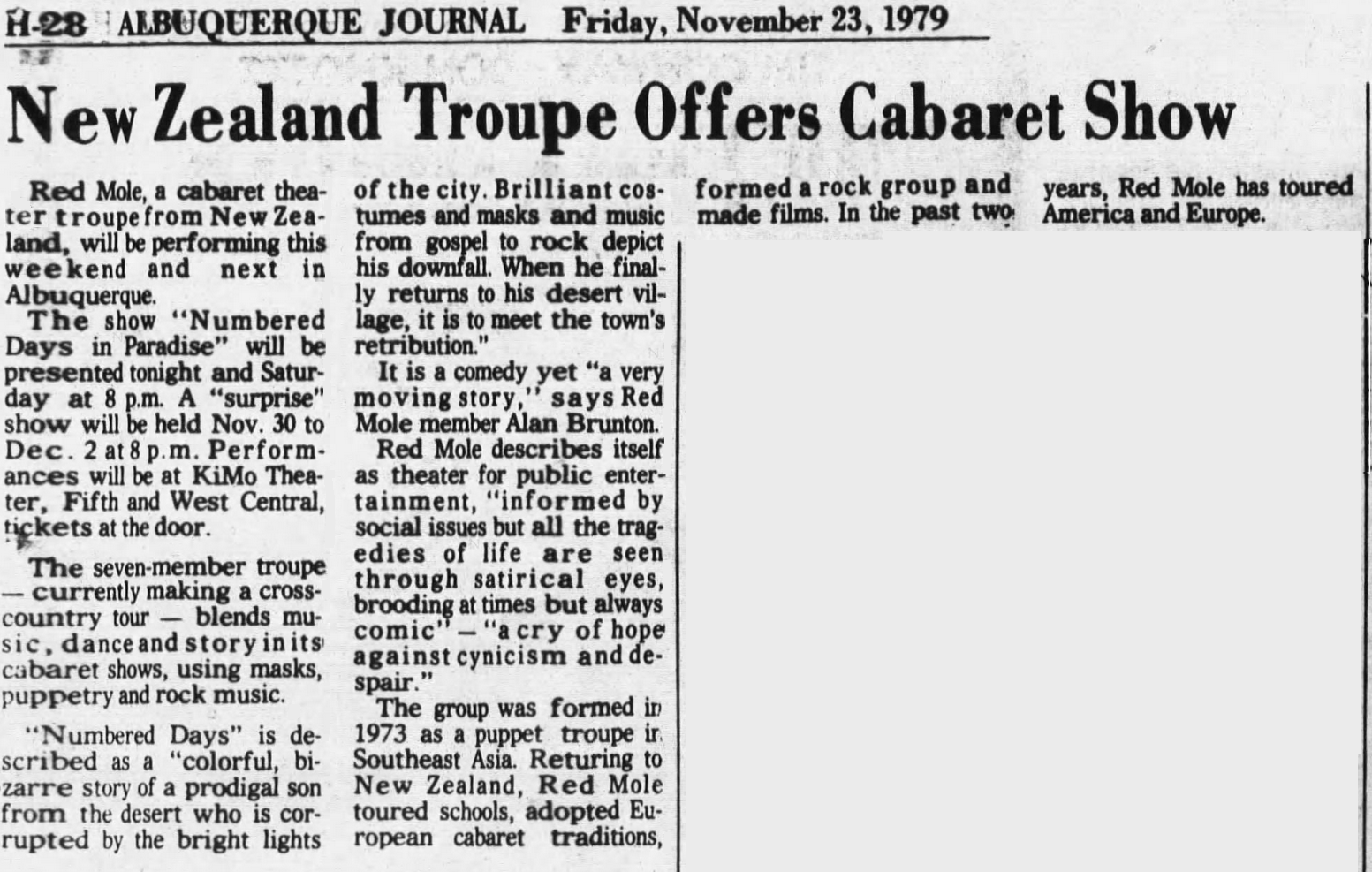

Albuquerque Journal vol. 98 no. 327, Friday, 23 November 1979, p. H-8

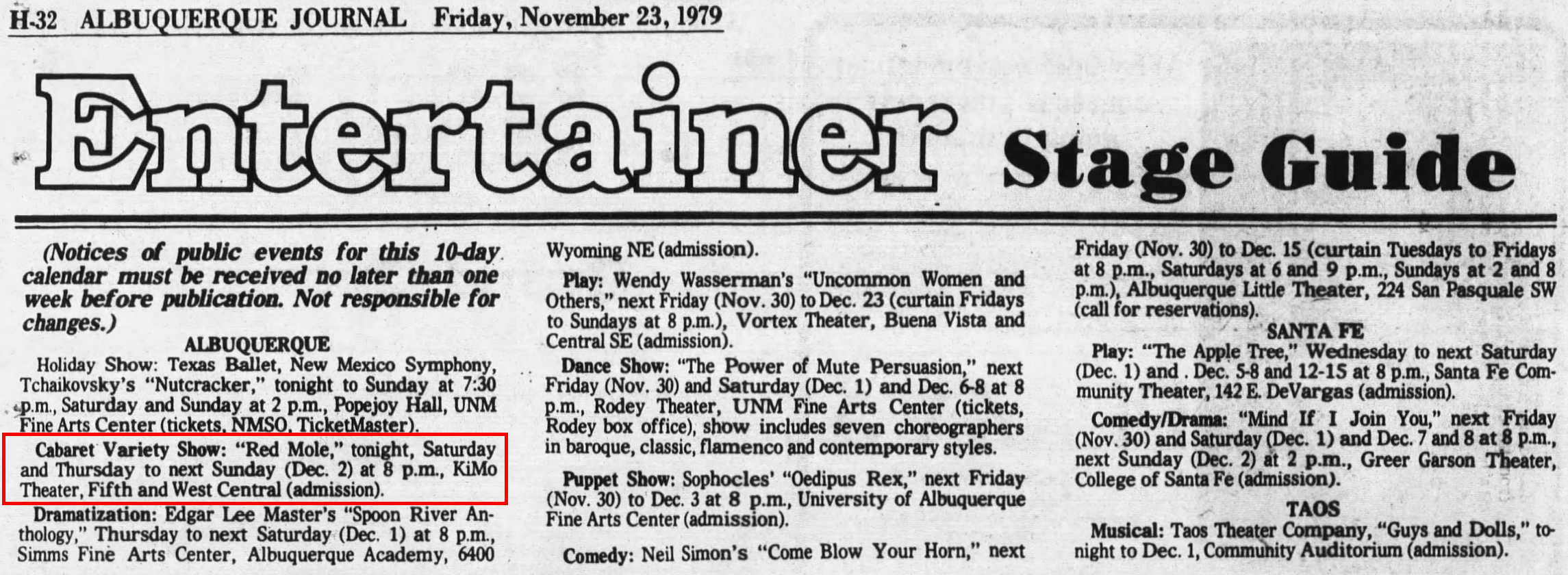

Albuquerque Journal vol. 98 no. 327, Friday, 23 November 1979, p. H-32

Albuquerque Journal vol. 98 no. 328, Saturday, 24 November 1979, p. B-4

Albuquerque Journal vol. 98 no. 329, Sunday, 25 November 1979, p. D-5

Albuquerque Journal vol. 98 no. 333, Thursday, 29 November 1979, p.

Albuquerque Journal vol. 98 no. 334, Friday, 30 November 1979, p. D-3

Albuquerque Journal vol. 98 no. 334, Friday, 30 November 1979, p. H-22

Since the Red Moles on stage at the Rodey mentioned that they were performing at the KiMo, I made up my mind to attend that dilapidated theatre.

In order to attend, though, I had to go through my father, he of the Vesuvian temper.

He was disgusted, sickened, infuriated by my choice of entertainment, yet, nonetheless,

he mysteriously agreed to pick me up after the Sunday-night show, since there were no buses running that late.

When I next saw John, I mentioned this to him.

He was amused.

He understood my father’s reaction.

Did I not know, he asked, that in that morning’s paper there was an angry letter to the editor

complaining about the Red Mole’s KiMo performance, which included such unsavory acts as two topless women with whips?

No, I had not known about that,

but for the performance I saw, which was Part Two only, there was no such offering on stage.

Now, in November 2018, after decades of wondering, I am at last able to see this letter to the editor,

courtesy of something called the Internet:

Wait a minute.

For all these decades, I was wondering what precisely was in that letter to the editor.

Then in late 2018 I finally looked at it, thanks to Newspapers.com, but the Editor’s Note at the end seemed too familiar.

I dismissed that as my imagination overworking itself, pretending to remember things that I never experienced.

Yet it keeps bothering me.

Now that I think about it some more, I know for certain that I saw Alfred Smith, Jr.’s, letter right after John told me about it.

If I saw it, though, why did I not clip it and put it into my Red Mole file?

It would have been entirely unlike me not to do that.

So as I ponder that conundrum, it occurs to me: I bet I did clip it and put it into my file,

but if I did so, it apparently got lost along with so many other of my possessions.

|

To go slightly

Here is a photo of the KiMo’s lobby and mezzanine, taken shortly before the grand opening of Monday, 19 September 1927.

Look carefully at the ballustrade in the mezzanine.

You will see that the bars are shaped like stylized turkeys.

1980 building codes mandated that the railings be higher,

and so instead of installing a new base for the turkeys,

or instead of simply adding a banister above the original,

the remodeling crew cut each turkey apart and welded in new iron rods to make their feet and necks longer.

The joins are more than plainly evident.

The remodeler joked that he had “fed the turkeys.”

Horrendous.

Note the doors in the lobby leading to the auditorium.

All bashed away and reconstructed in a different position, minus any hint of the original design.

Note the furnishings. Gone.

Here is a 1927 photograph of a portion of the auditorium.

Note the small organ grill with the three ornaments and four buffalo skulls above it.

I crawled inside of it in 1978.

Gone.

Compare the above image with a current photograph, which you can find

here.

Note that the organ grill is flanked on either side by a pilaster.

The pilaster on the left was destroyed and rebuilt in a different position.

Note the false doorway with the blanket decoration beneath the organ grill.

Gone.

That entire portion of the wall has been removed,

replaced by empty space to hang lights.

Note the position of the original proscenium.

The rebuilt proscenium has been recessed, for no sane reason I can possibly imagine.

The new curtains only partly match the originals.

Note the kachina frescoes on the wall.

Here’s the story.

There were others, not shown in this photograph, or in any photograph I have ever seen (I think some of the kachinas were added shortly after the grand opening).

Talkies were introduced here on Sunday, 14 July 1929, with Weary River,

and

|

Now let us return to the Red Mole’s show that unforgettable Sunday evening, the 2nd of December 1979.

There was no topless performance that night for Part Two,

nor was there anything scandalous or offensive in any way.

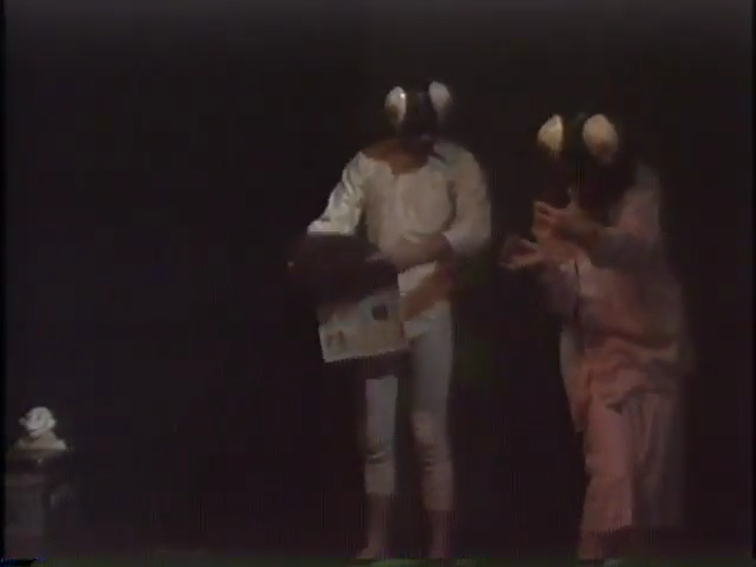

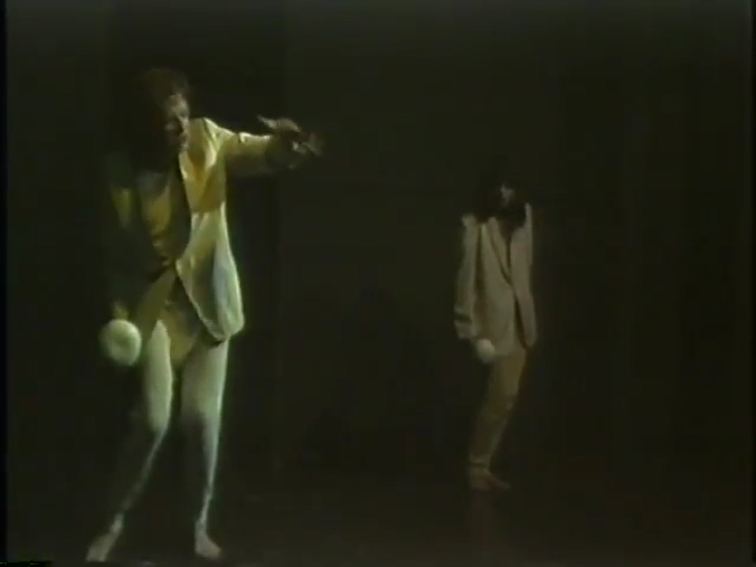

What was on stage was the most hypnotic, dreamlike, hallucinatory production I had ever seen,

accompanied by Jan Preston’s rock music.

With the rarest exceptions, I detest rock music, but this was the best exception of all.

The music was seductive, haunting, trance-inducing.

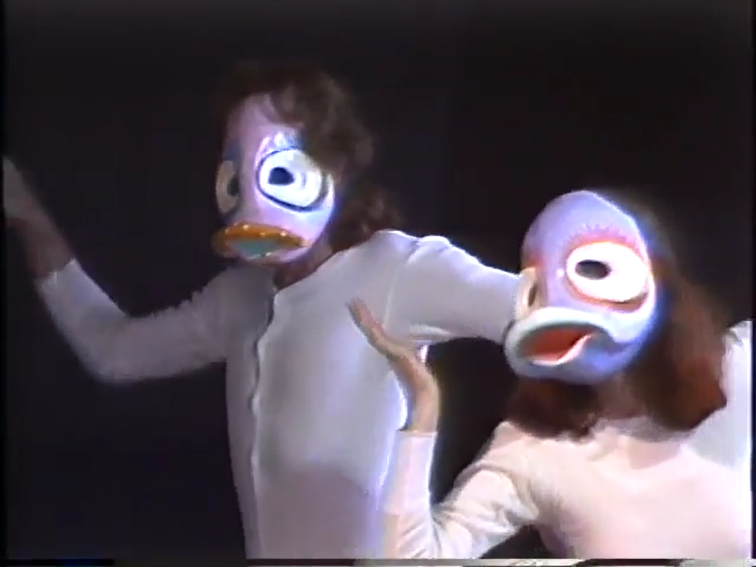

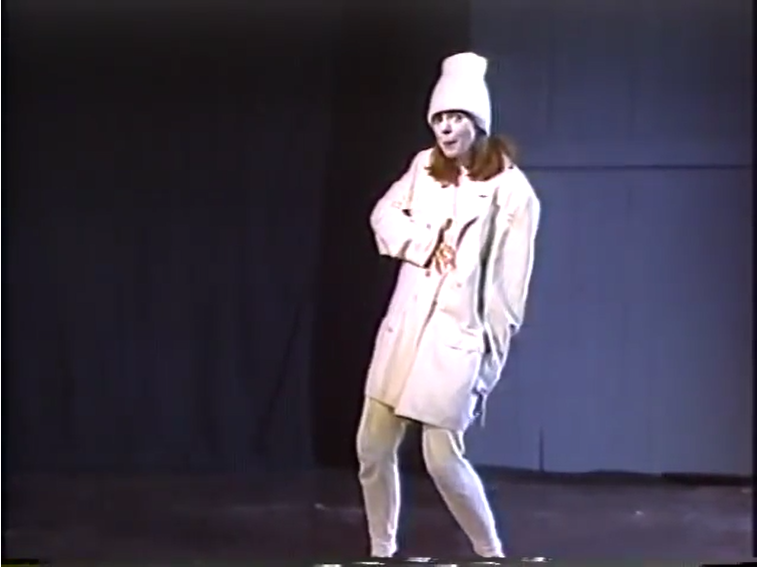

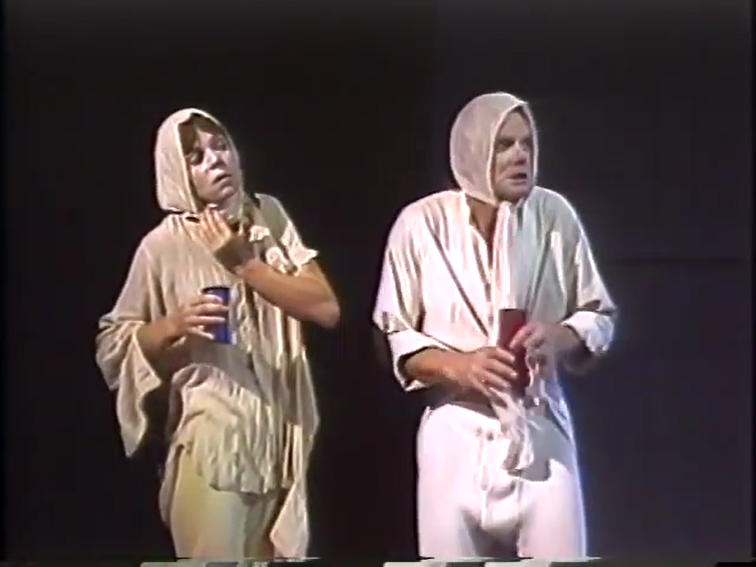

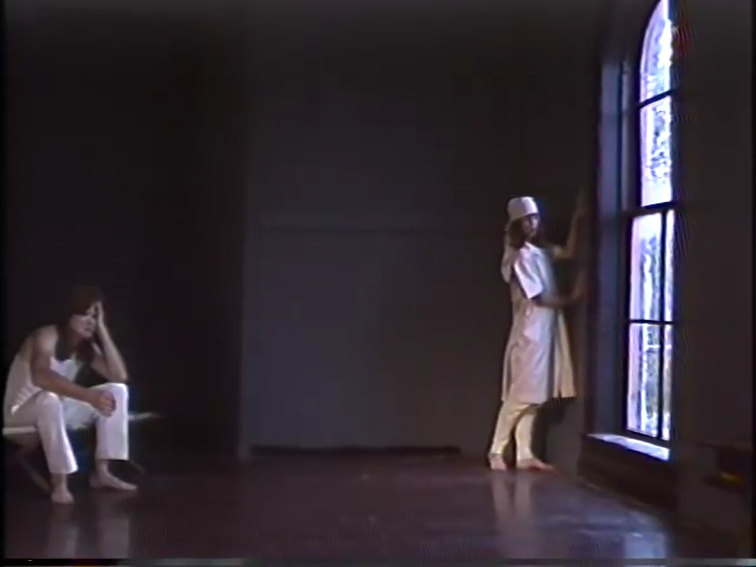

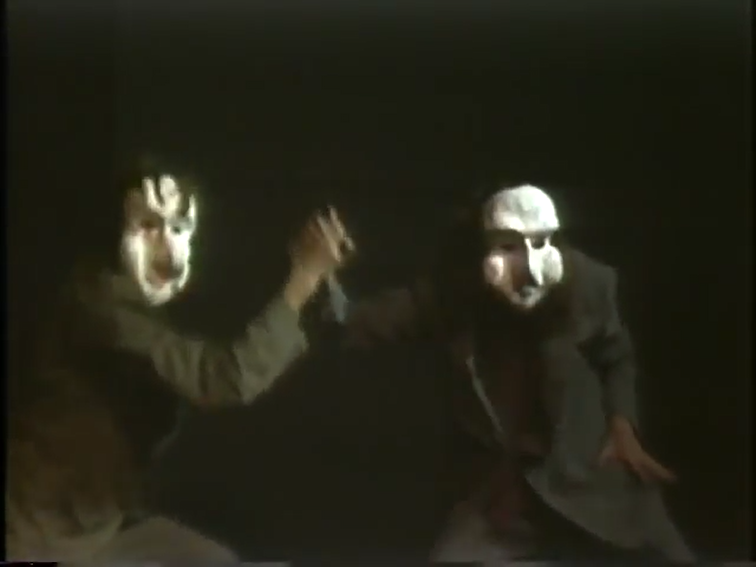

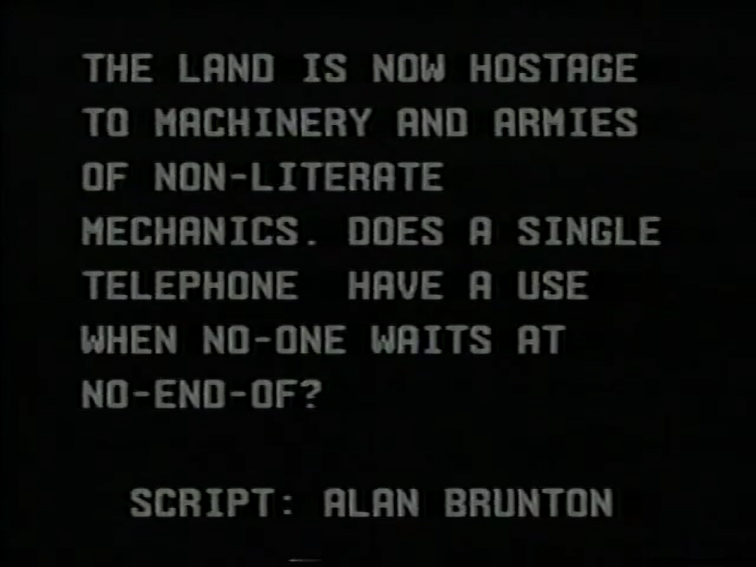

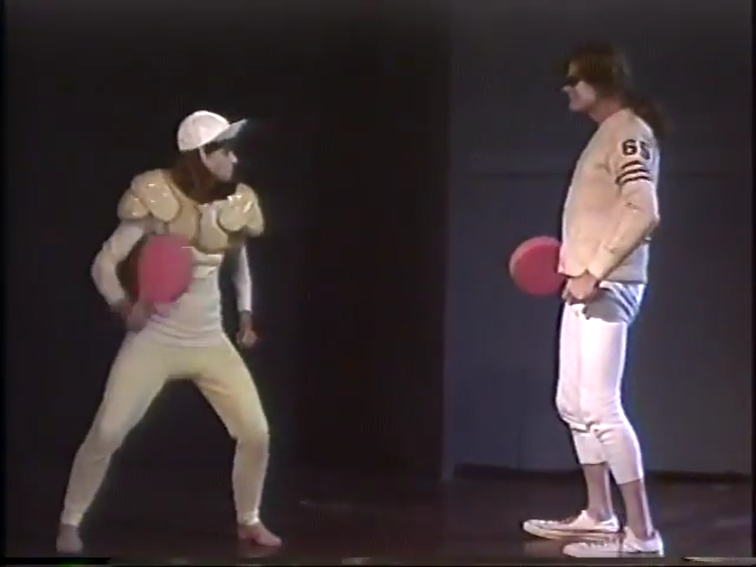

The show was modern dance and mime and visual allegory combined with animal masks and songs,

with everything narrated by poetry that was deliberately vague and often inscrutable.

No moment logically followed any previous moment, as the show continued to shape-shift erratically but somehow soothingly.

So there I was, watching a phantasmagorical performance of a non-narrative dreamlike script

inside a seedy and nightmarish slum building in a crime-ridden part of town after dark

while the mesmeric music lulled me into a reverie.

A thought came to my mind:

“I hope I remember this dream when I wake up.”

Then a split second later I realized I was not dreaming, that this was all real.

This happened not just once that evening, but over and over and over and over again.

To this day, Numbered Days in Paradise, Part 2, remains the finest performance I have ever seen, in any medium.

A few years later I asked Alan if the music had perchance been recorded, especially that hauntingly atmospheric piece entitled “Forbidden City.”

He was amused by my interest, but, alas, he said that no, it had never been recorded.

If the music was never recorded, then neither was the play.

Since no one on the planet will ever have another chance to see this production,

I would love at least to get a copy of the written score and the script.

An Incidental Note:

When state sponsors art, the result is comforting and usually bland.

State-sponsored art is not challenging, it is not revolutionary,

it does not question conventions, it is not provocative, it is not confrontational, it does not ridicule the very concept of authority,

it does not seek to rouse audiences out of their complacency and compel them to change their minds.

Apparently someone at City Hall made a mistake by booking the Red Mole’s show,

for the Red Mole committed all those sins — and more.

My thankfulness for that mistake knows no bounds.

Over the next few years, whenever the Red Mole gave a performance that I could attend,

I kept the programs, flyers, and anything I could possibly keep.

On a windy day in 2008 I went through my possessions in my storage locker in Fort Collins, Colorado, and decided to retrieve my Red Mole file folder.

I opened it and saw that everything I remembered was still there.

So I carefully stuffed it into a box along with a number of other items, went to the post office, and mailed it to myself.

When the box arrived at my lodgings a few days later, the Red Mole folder was missing.

I was devastated. What had I done wrong?

As soon as I could arrange another vacation, I went back to Fort Collins to look at my storage locker again.

A ha! Right there in front was my manilla folder labeled “Red Mole”! Yay!

I opened it, but it was nearly empty.

What had happened?

I concluded I must have dropped the contents while going through my things, and that the wind had taken care of the rest.

I was heartsick.

In October 2018 I went through my possessions once again.

By this time they were all in Albuquerque.

As I was digging through a plastic file crate of items related to silent-movie music,

what did I see but the missing contents of my Red Mole folder!!!!!

How did they get in there?

What on earth had induced me to put them in there?

What had I been thinking that windy day in Fort Collins? Or what had I not been thinking?

So now, at long last, I can share them with the world.

Click here to see the above brochure, unfolded.

Eventually, I’ll descreen thehalf-tones,

though that would be tricky for the image that is mixed with type.

Eventually, I’ll descreen the

though that would be tricky for the image that is mixed with type.

I was so overawed by the show that I spoke with cast and crew afterwards.

It was the only time in my life I was starstruck, and thus nearly dumbfounded.

Unlike many casts and crews, they were perfectly happy to chat with any audience member who cared to approach them.

Unlike many casts and crews, they had not even a hint of ego.

I took some notes on a piece of scratch paper. Here they are:

I have no memory of taking these notes.

Clearly they were dictated to me.

They make me chuckle.

Yes, on stage Alan certainly looked tall, but when I talked to him face to face, I was surprised to discover that we were exactly the same height, 5'8",

which is not exactly tall.

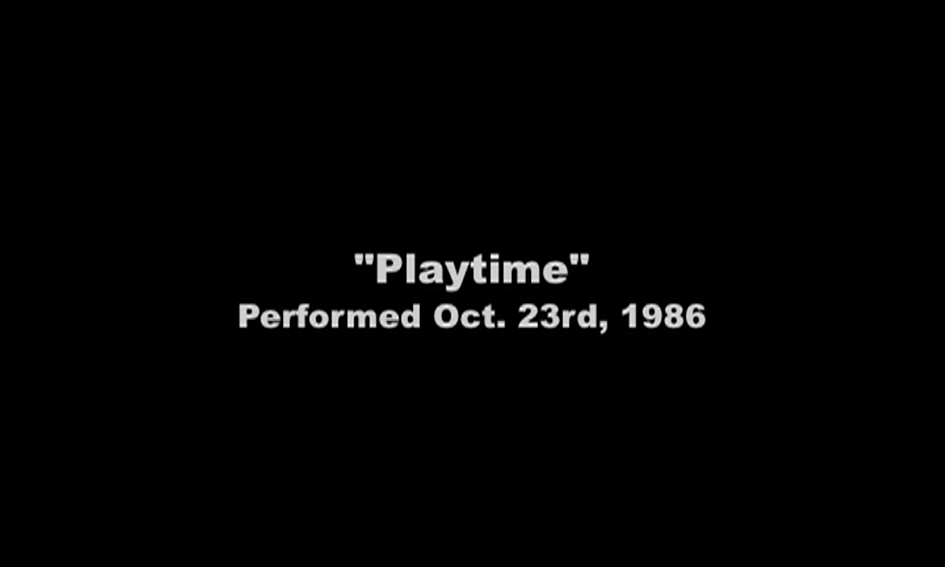

Below is a ticket stub from a performance in the ballroom at the SUB (Student Union Building) on the UNM campus.

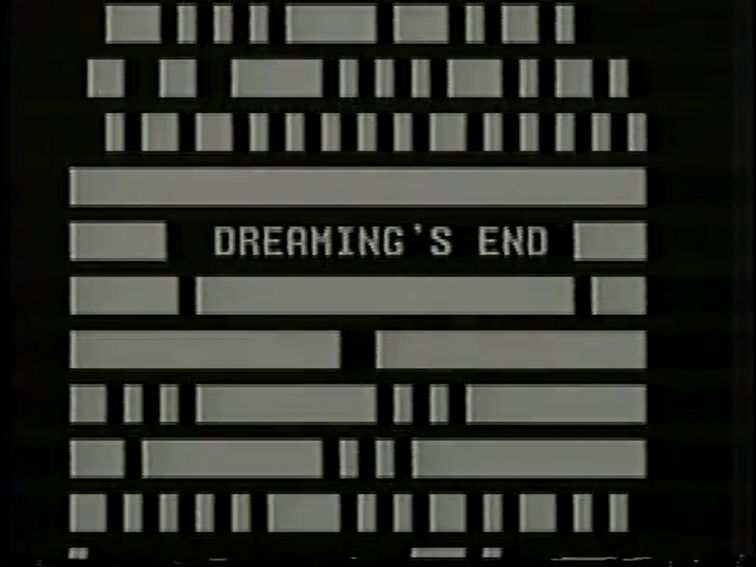

This must have been 1984, probably in November.

I think the title was Dreaming’s End, a title the group recycled for a video not long afterwards.

The above must have been on the ticket table when I attended the UNM Ballroom performance.

I did not attend the Central Torta Café show, surely because I was unable to.

It was likely a repeat of the show I had just witnessed.

This next show I did see, sitting on the floor along with the rest of the audience.

Parts of the play were screamingly funny, especially Alan’s opening olio, á la Jack Benny, George Burns, or Bob Hope.

Other parts induced a hypnotic state, especially the mime of the duelling imperialist invaders.

My memory is too vague, but I think it was at the Variant Gallery that the Red Mole

offered their chap book bound with yarn.

_thumb.png)