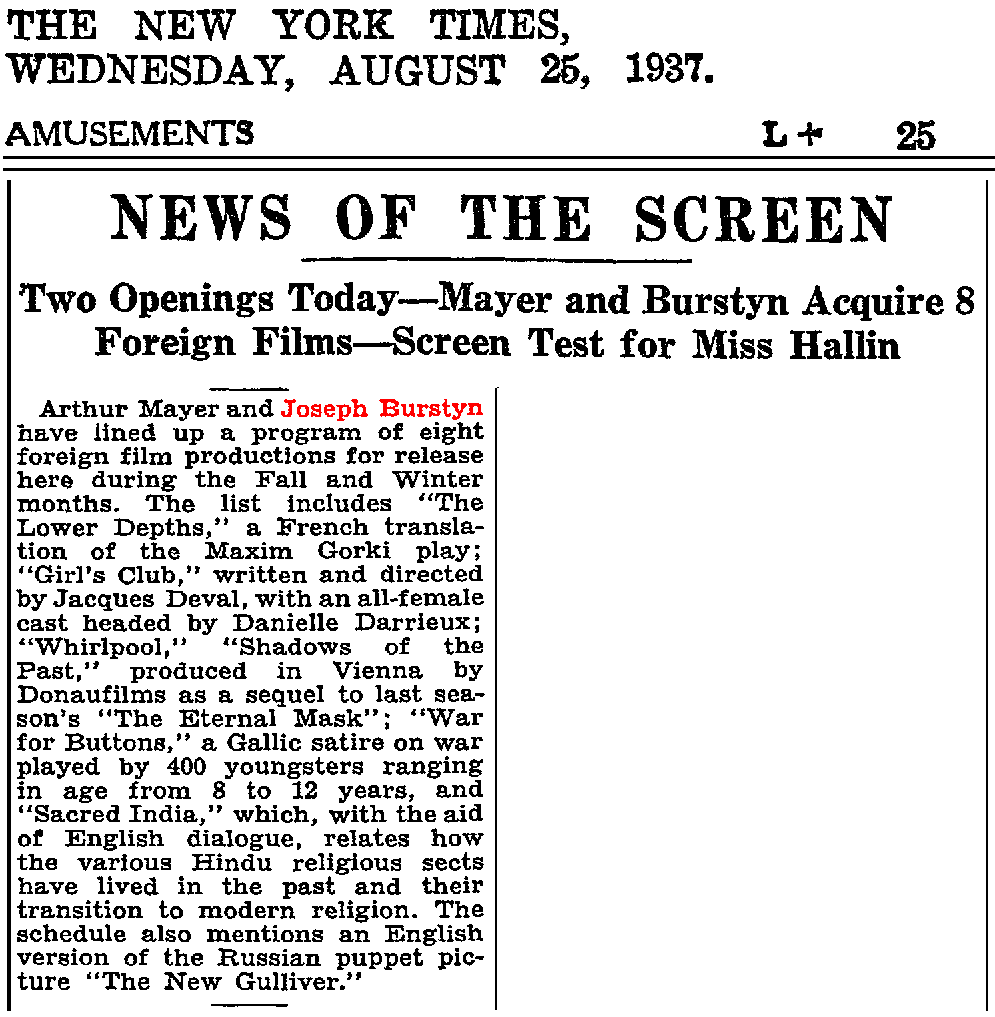

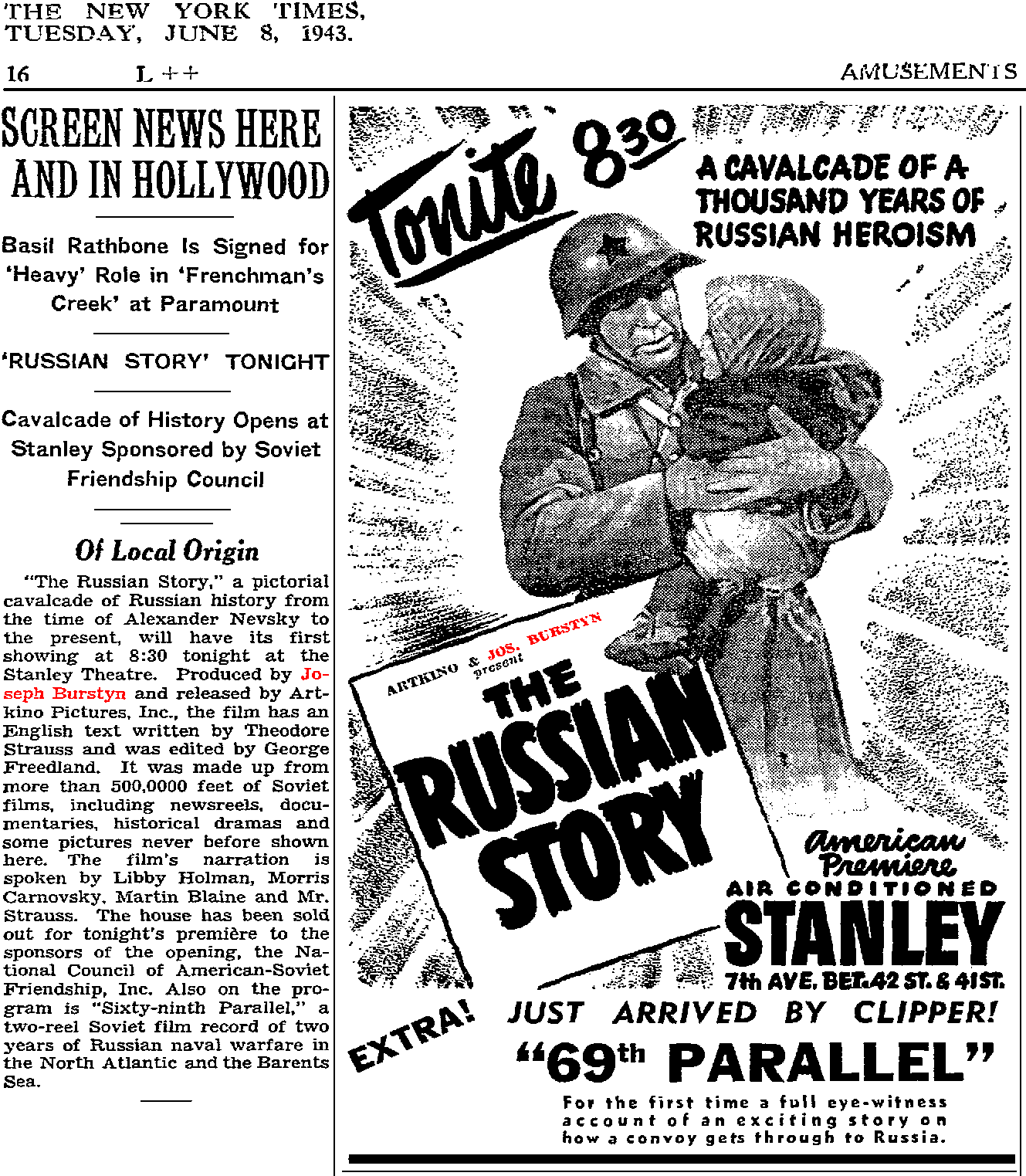

The New York Times

Sunday, 29 June 1952, sec 2 p 3:

Back in the 1970’s, in some reference work, somewhere,

I ran across a mention of this documentary on the World Assembly of Youth.

Maybe it was in a trade annual, maybe in a magazine article; I don’t remember.

(Wait! I found it! It was in the 1963 Current Biography.)

Then I ran across yet another reference, somewhere,

that Kubrick had possibly made other shorts for the State Department as well.

My vague memory is that a journalist asked what other State Department movies he had done,

but Kubrick declined to answer.

So for close to 40 years I’ve been wondering about this flick on the

World Assembly of Youth.

If you want misinformation, go to Wikipedia.

If you want real information, read on.

This is what little I know.

The World Assembly of Youth (WAY) was founded in London in 1948

as a Western (read: CIA) counteroffensive to the

Soviet-backed World Festival of Youth and Students.

After three years of preparation the first WAY conference began on Sunday, 5 August 1951,

and ran through Thursday, 16 August 1951,

at Cornell University.

See also:

| • |

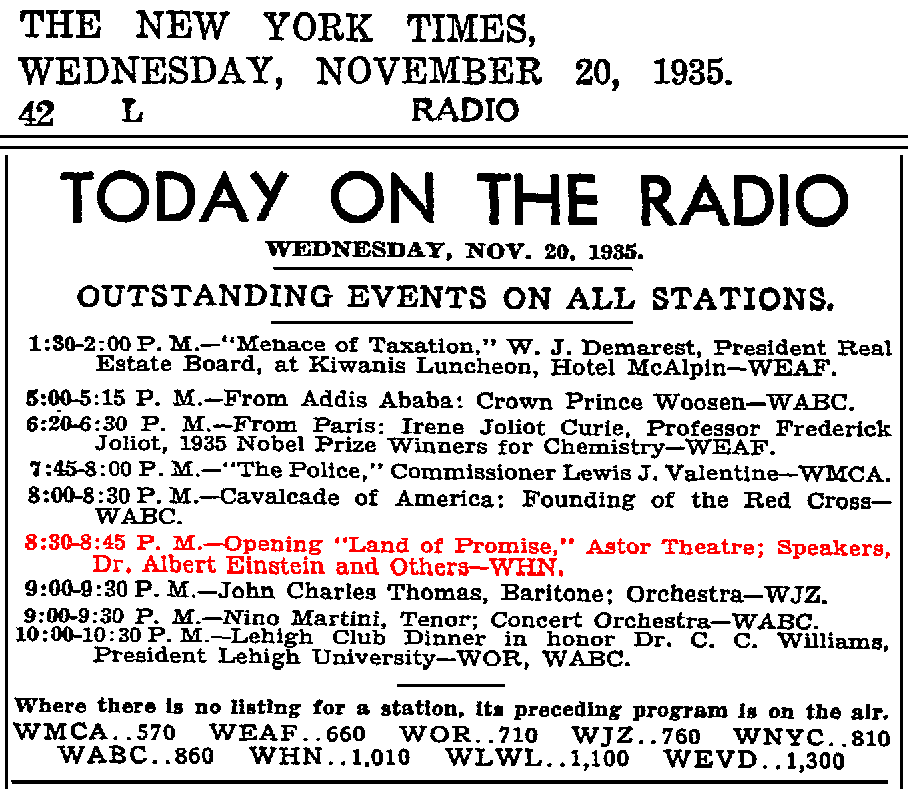

“World Youth Parley Is Discussed Here,” The New York Times,

Tuesday, 10 April 1951, p 29. |

| • |

“Mrs. Roosevelt to Speak Here for World Assembly of Youth,”

The Cornell Daily Sun 67 no 154,

Tuesday, 24 April 1951, p 5. |

| • |

“Youth Group Seeks Housing,” The New York Times,

Tuesday, 12 June 1951, p 23. |

| • |

“First Group Here for Youth Session: Anti-Communist Gathering at Cornell to Draw 500 from 60 Nations Next Month,”

The New York Times,

Thursday, 26 July 1951, p 5. |

| • |

“6 Japanese Arrive for Anti-Red Rally,”

The New York Times,

Friday, 27 July 1951, p 5. |

| • |

“Eisenhower Uses Jet Plane as Text: Talk at Netherland Ceremony Marking U.S. Craft Transfer Links Freedom to Unity,” The New York Times, Sunday, 29 July 1951, sec 1 p 17. |

| • |

“56 Arrive by Plane for Youth Assembly,” The New York Times, Saturday, 28 July 1951, p 6. |

| • |

“Vatican Prelate at St. Patrick’s: Cardinal Piazza Is Welcomed at Mass—Sermon Stresses Nation’s Spiritual Basis,” The New York Times, Monday, 30 July 1951, p 14. |

| • |

“Mayor Welcomes Youth Delegates: 150 from 63 Free Nations Are on Their Way to World Assembly at Cornell,” The New York Times, Tuesday, 31 July 1951, p 27. |

| • |

“The Eleanor Roosevelt Program,” Program 210, Tuesday, 31 July 1951, Franklin D. Roosevelt Presidential Library & Museum catalogue number 72-30(210). |

| • |

“Youths Meeting Here: Delegates to World Assembly Open Four-Day Session,” The New York Times, Wednesday, 1 August 1951, p 25. |

| • |

“Monteux Ends Stadium Stay,” The New York Times, Thursday, 2 August 1951, p 17. |

| • |

AP Wire, “Mrs. Roosevelt Entertains Delegates to World Assembly,” The New York Times, Friday, 3 August 1951, p 9. |

| • |

“Education Notes: Varied Activities on the Campus and in the Classroom — CORNELL—Youth Assembly,” The New York Times, Sunday, 5 August 1951, sec 4 p 9. |

| • |

“World News Summarized,” The New York Times, Monday, 6 August 1951, p 1. |

| • |

Warren Weaver Jr, “63 Nations’ Youth in a Miniature U.N.,” The New York Times, Monday, 6 August 1951, p 5. |

| • |

“Daughter of Nobel Prize Winner at Ithaca,” The New York Times, Tuesday, 7 August 1951, p 14. |

| • |

“Three Youth Rallies,” The New York Times, Tuesday, 7 August 1951, p 24. |

| • |

AP Wire, “Mrs. Roosevelt Sees Hard Job for Youths,” The New York Times, Thursday, 9 August 1951, p 5. |

| • |

AP Wire, “Youth Group Shapes Worldwide Program,” The New York Times, Saturday, 11 August 1951, p 13. |

| • |

AP Wire, “Youth Delegates Go on an America-Style Picnic,” The New York Times, Monday, 13 August 1951, p 19. |

| • |

“Harry S. Truman Library & Museum” diary for Tuesday, 14 August 1951. |

| • |

Warren Weaver Jr, “Acheson Condemns ‘Regimented’ Path: Tells World Youth Assembly, over Telephone, It Spells the ‘Degradation’ of Man,” The New York Times, Tuesday, 14 August 1951, p 9. |

| • |

“Youth, 1951,” The New York Times, Tuesday, 14 August 1951, p 22. |

| • |

Warren Weaver Jr, “Youth Assembly Approves Aid Plan: World Group Votes Resolution for Technical Assistance to Underdeveloped Areas,” The New York Times, Wednesday, 15 August 1951, p 11. |

| • |

“Youth Parley Urges End to Travel Curbs,” The New York Times, Thursday, 16 August 1951, p 15. |

| • |

AP Wire, “Youth Group Hails U.S.: First World Assembly Meeting Ends on Cornell Campus,” The New York Times, Friday, 17 August 1951, p 6. |

| • |

“Letters to The Times: Youth Assembly Praised,” The New York Times, Saturday, 18 August 1951, p 10. |

| • |

AP Wire, “Youth Head Re-Elected: Sauve of Montréal Named to 3d Term by Assembly Council,” The New York Times, Wednesday, 22 August 1951, p 21. |

| • |

“Letters to The Times: Moslems Under India’s Rule — Their Status Reviewed in Questioning Stand of Pakistan,” The New York Times, Tuesday, 28 August 1951, p 22. |

| • |

“f.o.i.” (For Our Information), 29 September 1951 (4th typewritten page). |

| • |

Joel Kotek, Students and the Cold War tr by Ralph Blumenau (NY: St. Martin’s Press, 1996). |

| • |

David Maunders, “Controlling Youth for Democracy: the United States Youth Council and the World Assembly of Youth 1946–1986,” Commonwealth Youth and Development 1 no 2, 2003, pp 22–51. |

| • |

Holger Thuss and Bence Bauer, Students on the Right Way: European Democrat Students 1961–2011 (Brussels, European Democrat Students/Centre for European Studies, May 2012), pp 154–155. |

My old, disproved, guess as to what really happened:

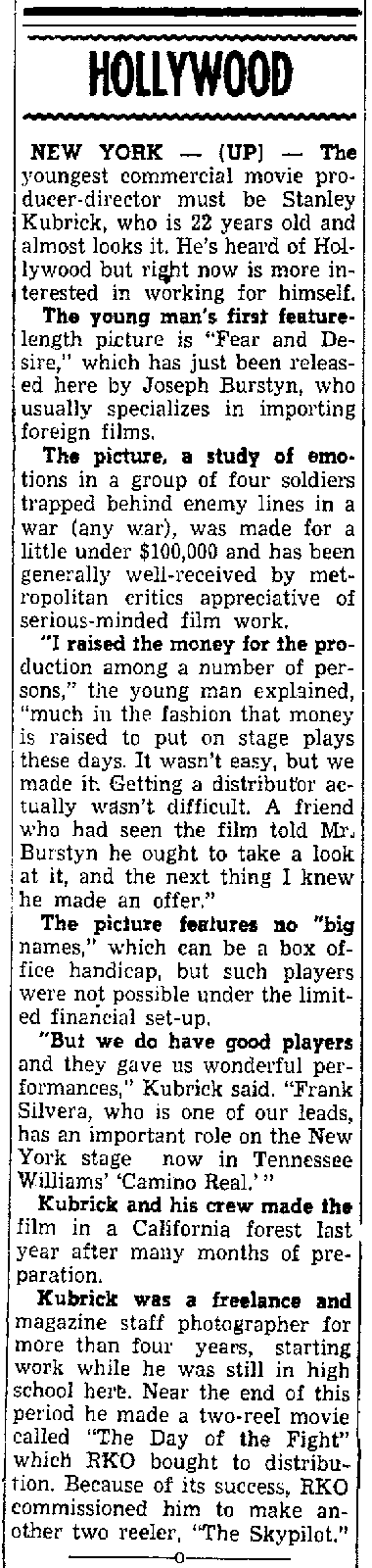

Apparently Kubrick somehow got a gig to do a promo on this conference.

My guess is that at the end of the conference, the State Department collected all of Kubrick’s footage and said

“You’ll be hearing from us soon,” and I bet Kubrick never heard from them again.

I assume the footage was never assembled, and the movie was probably never even given a title.

It’s probably in a forgotten banker’s box

somewhere in a storage unit rented by the State Department.

Oh, heavens to Betsy!

That was my guess, and my guess was dead wrong.

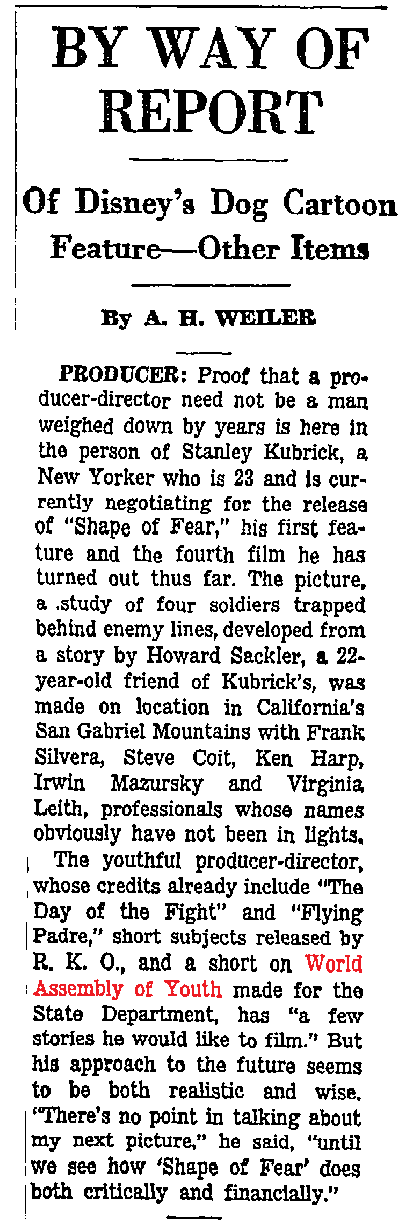

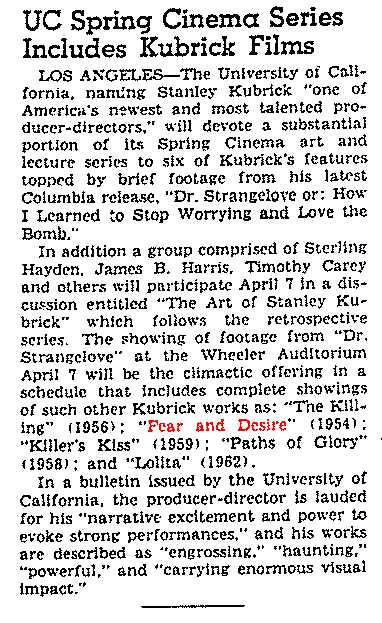

In late 2020, a renowned Kubrick scholar told me I should pre-order

James Fenwick’s new book,

Stanley Kubrick Produces.

I ordered the cloth-bound edition, which is actually not cloth; it’s coated cardboard.

Nice.

Fenwick found World Assembly of Youth and plopped it onto YouTube.

There are no credits on it at all, but that didn’t stop Fenwick from obtaining the full list of credits,

which nowhere mention Stanley.

Now, go-getting Stanley had a tendency to take more credit than he was due.

Okay.

Did he just hear about this obscure movie somehow, see that there were no credits on it,

and take it upon himself to claim credit?

I don’t think so.

He must have been involved somehow, perhaps as a unit photographer, or perhaps as an assistant director,

or perhaps as an uncredited member of the camera crew.

Another possibility: Perhaps he was replaced before he began his new job.

Impossible to tell.

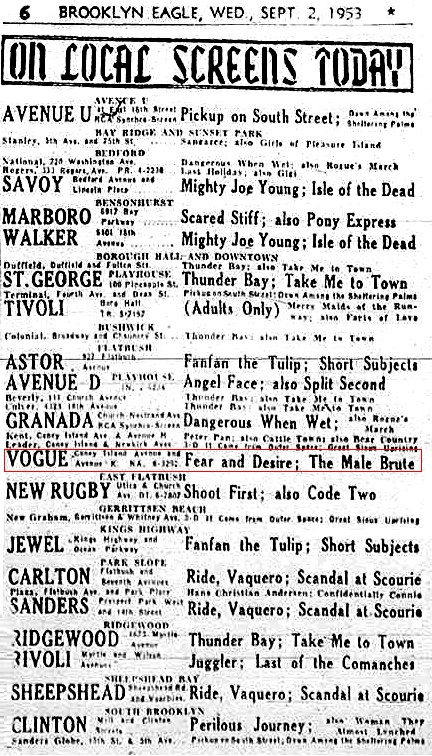

I would love to get a full list of playdates for this movie.

Ya know what’s sad about this movie?

What’s sad is that the idea for WAY was good, but it was never permitted to be more than an idea.

A bunch of youth from around the globe descend upon lovely Ithaca, New York,

and have intelligent conversations, discussions, round-tables, lectures on how to fix the world.

They have good ideas, but there is no mechanism by which to put these ideas into practice.

This reminds me of the IHEU, which was the same thing.

There was no political involvement, no political influence, none, none whatsoever.

The WAY, like the IHEU, had no means of passing laws, dictating policy, or even influencing policy.

It was not civic engagement; it was just an illusion to make people feel better.

People meet, talk, and go away — and nothing changes.

|

_CkW8v_qbQbI.png)