Joseph Frank “Buster” Keaton

Buster Keaton (4 October 1895 – 1 February 1966, lung cancer)

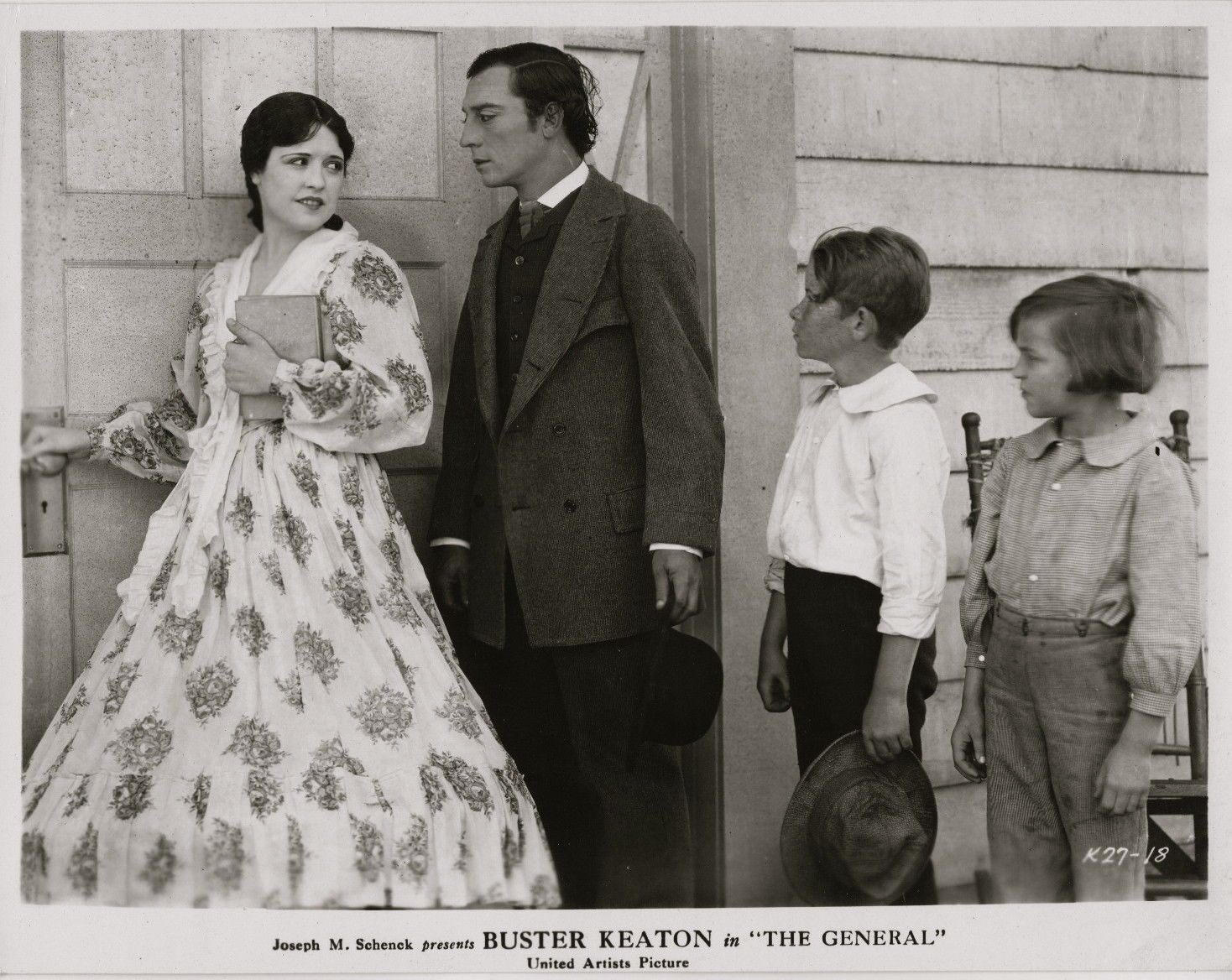

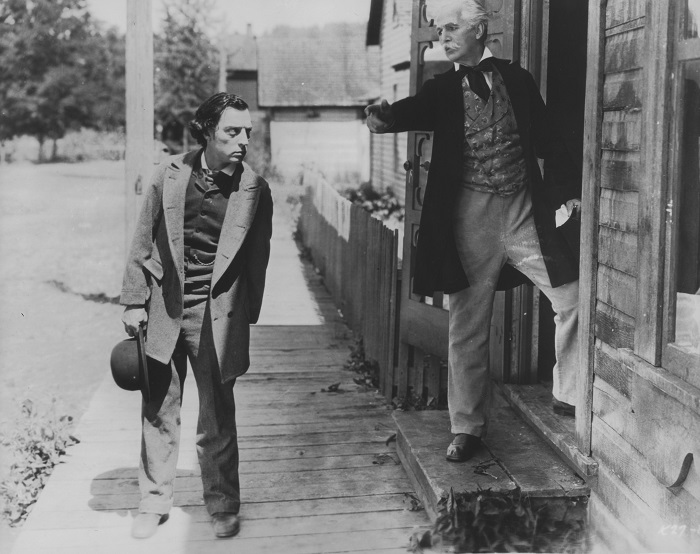

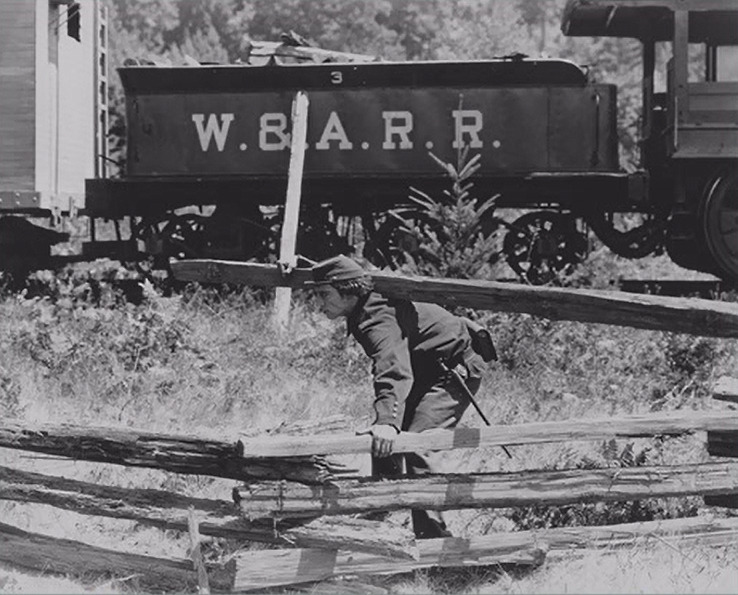

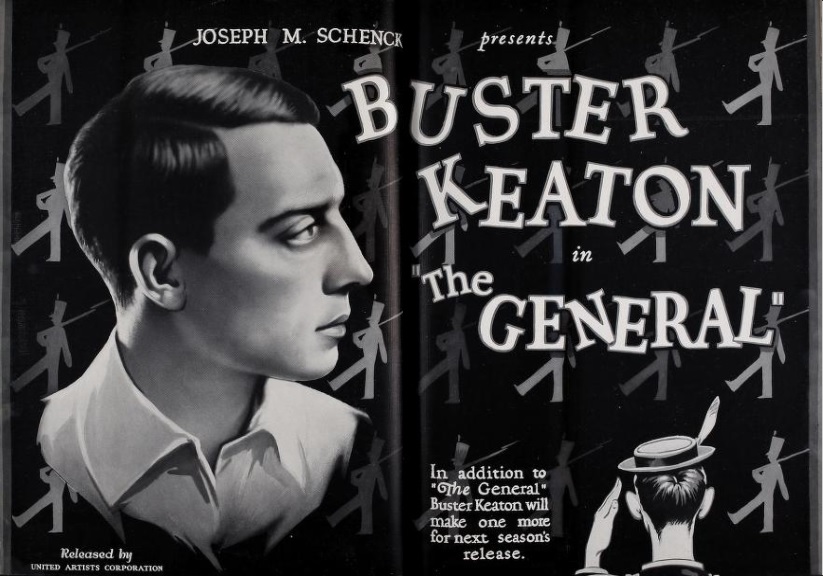

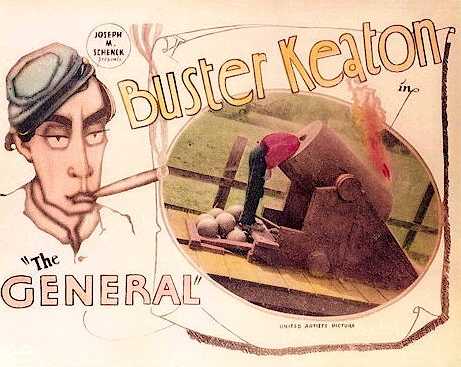

sometimes said that The General was one of his finest movies;

sometimes he said it was his finest of all.

But in his autobiography, My Wonderful World of Slapstick,

he mentions it in passing only three times

(pp. 175, 201, and in the unpaginated illustrations).

Keaton was born in a boarding house in Piqua, Kansas,

where his parents, Joseph Hallie Keaton and Myra Cutler Keaton,

were touring with a medicine show.

He made his debut at the age of nine months when he crawled out of the dressing room onto the stage,

and he became part of the act when he was three.

The young Keaton got his nickname within the first two years of his life

when he fell down a flight of stairs and landed unhurt and unfazed.

Legend has it that it was Harry Houdini who picked him up in wonderment and commented,

“That’s some buster you took.”

More recent research by Patty Tobias reveals that Joe Keaton, in his press releases over the years,

routinely changed the story and credited different vaudevillians as having given Buster his nickname.

Regardless of who made that chance remark, father Keaton immediately thought out loud:

“That would be a good name for him.”

The young Keaton was one of the first people in history to go by that nickname.

(George Wead, in a posting I cannot now locate, found a few previous Busters.)

Baby Buster imitated everything he saw everyone do, and he imitated his father’s tumbling and acrobatics.

Soon he learned how to take falls without getting hurt (surely the elder Joe assisted in these lessons, though Buster had no memory of such),

and the family’s rough-house act

had little Buster used as a mop, hurled against scenery,

dropped into the orchestra, and slammed against the back-stage wall.

This was all acrobatics, carefully rehearsed and choreographed, and it

caused mirth and merriment, but also led to the Gerry Society (Gerry with a hard “g”)

to institute proceedings on behalf of the seemingly abused child.

Court investigations revealed that the young Buster had no bruises or scars,

and that there was no evidence of abuse.

Keaton, his family, friends, and fellow vaudevillians, even into their old age,

all confirmed that the courts were right, and that the allegations of abuse were woefully mistaken.

(If you want to learn some of Buster’s basic moves, one step at a time, you can watch

this video.)

Buster was the star of the show, with ads sometimes reading

“BUSTER, assisted by Joe and Myra Keaton.”

Despite enduring audience appeal, while touring in the Keith-Albee circuit the Keatons were not a first-tier act.

They usually ranked fifth, sixth, or seventh in an eight-act show.

Buster learned to sing, dance, and get by with a guitar or ukulele.

He also learned magic and juggling, and was the Buff in a team called Buff & Bogany,

the Lunatic Jugglers.

(Thanks to Ron Pesch of Muskegon for making that last discovery!)

Keaton was born in a boarding house in Piqua, Kansas,

where his parents, Joseph Hallie Keaton and Myra Cutler Keaton,

were touring with a medicine show.

He made his debut at the age of nine months when he crawled out of the dressing room onto the stage,

and he became part of the act when he was three.

The young Keaton got his nickname within the first two years of his life

when he fell down a flight of stairs and landed unhurt and unfazed.

Legend has it that it was Harry Houdini who picked him up in wonderment and commented,

“That’s some buster you took.”

More recent research by Patty Tobias reveals that Joe Keaton, in his press releases over the years,

routinely changed the story and credited different vaudevillians as having given Buster his nickname.

Regardless of who made that chance remark, father Keaton immediately thought out loud:

“That would be a good name for him.”

The young Keaton was one of the first people in history to go by that nickname.

(George Wead, in a posting I cannot now locate, found a few previous Busters.)

Baby Buster imitated everything he saw everyone do, and he imitated his father’s tumbling and acrobatics.

Soon he learned how to take falls without getting hurt (surely the elder Joe assisted in these lessons, though Buster had no memory of such),

and the family’s rough-house act

had little Buster used as a mop, hurled against scenery,

dropped into the orchestra, and slammed against the back-stage wall.

This was all acrobatics, carefully rehearsed and choreographed, and it

caused mirth and merriment, but also led to the Gerry Society (Gerry with a hard “g”)

to institute proceedings on behalf of the seemingly abused child.

Court investigations revealed that the young Buster had no bruises or scars,

and that there was no evidence of abuse.

Keaton, his family, friends, and fellow vaudevillians, even into their old age,

all confirmed that the courts were right, and that the allegations of abuse were woefully mistaken.

(If you want to learn some of Buster’s basic moves, one step at a time, you can watch

this video.)

Buster was the star of the show, with ads sometimes reading

“BUSTER, assisted by Joe and Myra Keaton.”

Despite enduring audience appeal, while touring in the Keith-Albee circuit the Keatons were not a first-tier act.

They usually ranked fifth, sixth, or seventh in an eight-act show.

Buster learned to sing, dance, and get by with a guitar or ukulele.

He also learned magic and juggling, and was the Buff in a team called Buff & Bogany,

the Lunatic Jugglers.

(Thanks to Ron Pesch of Muskegon for making that last discovery!)

When Joe Keaton’s mid-life crisis induced a bout with alcoholism,

and hence poor timing and great risk, his wife Myra broke up the act and the twenty-one-year-old Buster left with her.

Buster visited his family’s agent, Max Hart, and announced his availability.

Hart scheduled him for The Passing Show of 1917, in which Keaton hoped to do a wordless sketch.

Before his engagement commenced, a chance encounter with his old vaudeville buddy, Lou Anger,

led to a visit to the studio of fellow Kansan

Roscoe Arbuckle.

Buster had just seen Arbuckle’s latest, The Waiter’s Ball,

which had stolen a routine that the Keatons had originated and made famous,

and he was not looking forward to the meeting.

To his surprise, though, the two of them hit it off famously,

and within minutes Arbuckle asked Keaton to do a turn in The Butcher Boy,

which had just started filming.

Before the end of the day, Buster was in love with the movies.

He canceled his $250-a-week Passing Show contract

and signed on with Arbuckle’s studio for $40 a week.

He quickly became Arbuckle’s principal gagman, even inventing special effects.

After a few films, Buster was codirector and, effectively, costar.

When Joe Keaton’s mid-life crisis induced a bout with alcoholism,

and hence poor timing and great risk, his wife Myra broke up the act and the twenty-one-year-old Buster left with her.

Buster visited his family’s agent, Max Hart, and announced his availability.

Hart scheduled him for The Passing Show of 1917, in which Keaton hoped to do a wordless sketch.

Before his engagement commenced, a chance encounter with his old vaudeville buddy, Lou Anger,

led to a visit to the studio of fellow Kansan

Roscoe Arbuckle.

Buster had just seen Arbuckle’s latest, The Waiter’s Ball,

which had stolen a routine that the Keatons had originated and made famous,

and he was not looking forward to the meeting.

To his surprise, though, the two of them hit it off famously,

and within minutes Arbuckle asked Keaton to do a turn in The Butcher Boy,

which had just started filming.

Before the end of the day, Buster was in love with the movies.

He canceled his $250-a-week Passing Show contract

and signed on with Arbuckle’s studio for $40 a week.

He quickly became Arbuckle’s principal gagman, even inventing special effects.

After a few films, Buster was codirector and, effectively, costar.

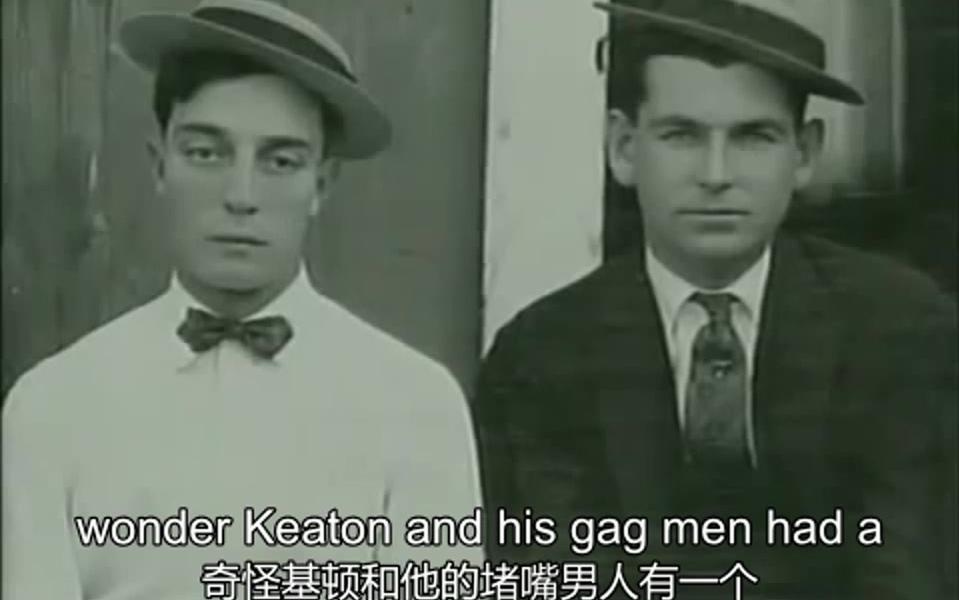

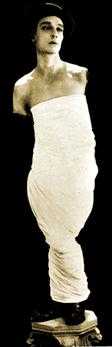

.jpg)

Photograph by Albert Walter Witzel (1879–1929).

This photo seems to be from circa 1917 or 1918.

Underneath “Witzel” is a code, “H.A.”

No idea what that means.

The £2,750 ($3,580.40) price is a bit beyond my budget.

In 1920, Arbuckle won a (tragically short-lived) contract for feature films with Paramount Studios,

and Buster’s producer and future brother-in-law Joe Schenck (pronounced Skenk)

gave Buster his own studio.

Buster here made nineteen short films over the next three years,

and, in 1923, he was finally allowed to make features, which he had wanted to do from the first.

While the shorts were filled with impossible stories and rapidly paced gags,

most of his independent features were revolutionary.

His less-is-more method of storytelling demanded that his performers underact.

Seldom in a Keaton feature do actors smile or frown or shout or cry or laugh.

The feature films that Buster made during the next five years

are notable for their striking compositions and camera work, their fluid editing,

their lack of sentimentality, and their absence of heroes or villains.

One of Buster’s strengths was irony,

showing how different perspectives lead to surprisingly different points of view.

As simple as his plotlines were, they were strict, disciplined, and strong.

He had an intuitive narrative gift,

but he did not learn story construction from performing knockabout routines on vaudeville stages,

nor did he learn it from his teams of gag writers.

He learned it elsewhere, perhaps through such books as Albright’s

The Short Story

or Pain’s

First Lessons in Story-Writing.

I wish I knew.

Sadly, most of his best features were laden with boy-gets-girl plot lines,

most likely imposed by his producer’s insistence upon ensuring success with a proven formula.

The General showed Buster at his most independent and uncompromising.

Clyde Adolf Bruckman

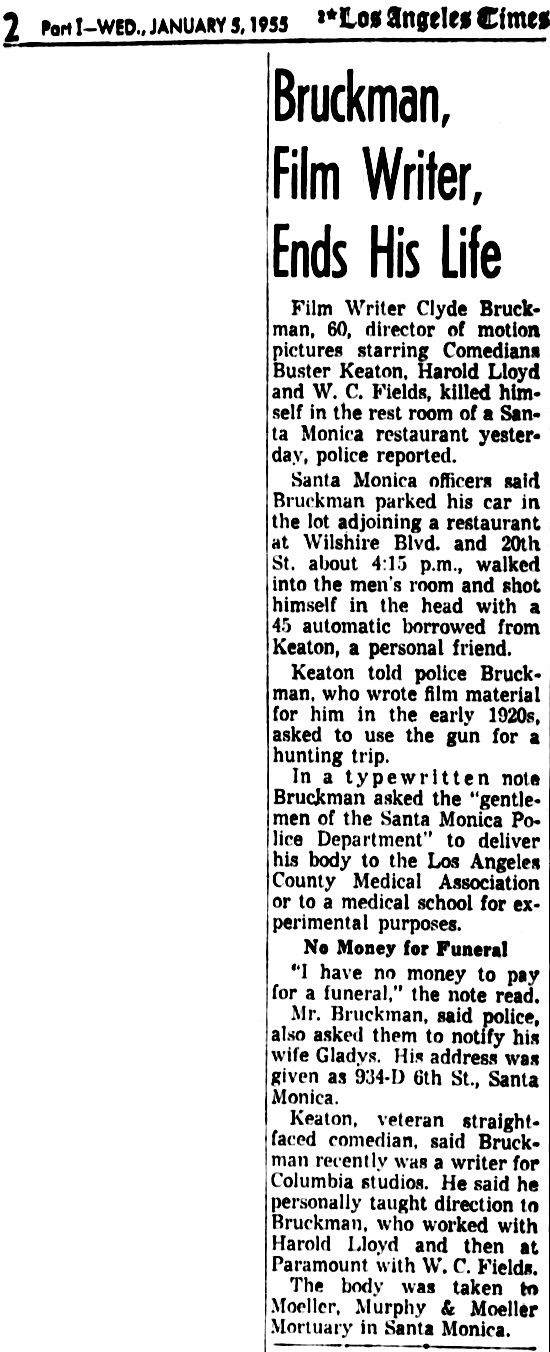

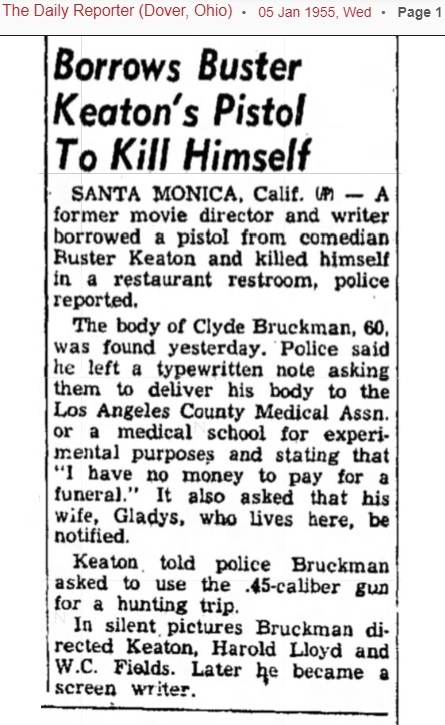

Clyde Bruckman (20 September 1894 – 4 January 1955, suicide)

was among the most highly sought-after gag men, comedy writers, and comedy directors,

but almost nothing is known about him, and nothing at all is known about his specific contributions.

Film historian Steve Massa supplied a brief sketch for a film program:

Bruckman came from a newspaper background and became a writer and gagman in 1919 for Eddie Lyons & Lee Moran and Monty Banks. In 1921 he joined Keaton’s staff of ideamen and was one of his key collaborators until he began freelancing after Seven Chances (1925). Besides being an important (and sometimes uncredited) collaborator to Harold Lloyd for almost fifteen years and directing Laurel and Hardy in some of their most important early comedies (Putting Pants on Philip [1927], Battle of the Century [1927], The Finishing Touch [1928], etc.), Bruckman also worked with Mack Sennett, Hal Roach, Max Davidson, W. C. Fields, Lloyd Hamilton, and the Three Stooges.

Bruckman’s fatal flaw was alcohol. As the 1930s rolled around he would go on binges and disappear in the middle of shoots. While this effectively ended his directing career, he was still in demand as a writer. But he had a penchant for recycling material he had written for other people and in the 1940s Harold Lloyd sued Universal and Columbia over material Bruckman revised — leaving Bruckman pretty much unemployable. In the early 1950s he managed to work on Keaton’s and Abbott and Costello’s television shows but not much else. In 1955 he borrowed a pistol from Keaton and shot himself.

For the longest time, I was unable to find any news items about this, nor could I find obituaries,

but now I see that there were two items, one local and one syndicated by the Associated Press.

Not long before Bruckman’s death, Rudi Blesh interviewed him for his book, Keaton (pp. 148–152):

“I was with Warner Brothers,” Bruckman related. “Warners at that time consisted of Jack, Sam, and Harry Warner, Monte Banks, and a few extras and props, in an old barn of a studio at Bronson and Sunset, where the big bowling alley now is.

“Then I ran into Harry Brand, an old friend of mine from newspaper days. Now he was Buster’s publicity man.

“‘Why don’t you come over with Keaton?’ he asked.

“‘How do I know Keaton wants me?’

“Next day Brand phoned, said ‘Come over for lunch with us.’

“I did and was hired, to start the next Monday. I went back and saw Jack Warner. ‘Jack, I have a chance to go with Keaton — better job, better opportunity. I’d like to close Saturday.’

“‘Can you keep a little secret?’ said Jack. ‘We’re all closing Saturday.’

“And, by gosh, they did — for six months or more. It took a German police dog called Rin Tin Tin to take them out of the red.”

Then Bruckman described the Keaton lot. “I suppose writers should coin phrases, so here goes,” he said. “We were one big happy family. And that’s something you don’t know until — and if — you’ve been in one. In such a situation, gags are never a problem. You feel good. Your mind’s at ease, and working.

“I was at Buster’s house or he at mine four or five nights many a week — playing cards, horsing around, dodging the issue. Then, at midnight, to the kitchen, sit on the sink, eat hamburgers, and work on gags until three in the morning. And how we’d work!

“You can’t match that today, when you walk in on a supervised production, cut and dried, every cough scripted and every sneeze timed, and the bigwigs all a pushbutton’s length from the set. Joe Schenck was too big to be a bigwig. He’s said — and I’ve heard him — ‘Tell me from nothing. Go ahead, what should I know about comedy?’

“Buster was a guy you worked with — not for. Oh, sure, it’s a cliché, like the ‘happy family.’ But try it some time. I even hate to mention the playing. It sounds like a buildup. But late afternoons we chose sides and had our ball game — fights, arguments. Rainy days it was bridge in a dressing room — fights, arguments. And we made pictures.” Bruckman sighed. “Harold Lloyd was wonderful to me,” he said. “So was Bill Fields. But with Bus you belonged.

“Well, it’s all changed, anyway. So organized and big a man can’t touch it. It used to be our business. We acted in scenes, set up scenery, spotted lights, moved furniture — hell, today even the set dresser with paid-up dues can’t move a lousy bouquet. He sits and waits until the ‘green man’ arrives. An actor has to fight his way onto the set through technicians, supervisors, experts, and accountants. And television has followed the same lines. So....” He swallowed and looked up. “Other days, other ways, as Nero said.

“Oh, we’d get hung up on sequences. Throw down your pencils, pick up the bats. The second, maybe third, inning — with a runner on base — Bus would throw his glove in the air, holler, ‘I got it!’ and back to work. ‘Nothing like baseball,’ he always said, ‘to take your mind off your troubles.’

“With it all, you wouldn’t believe a comedian could be so serious. He showed them all how to underact. He could tell his story by lifting an eyebrow. He could tell it by not lifting an eyebrow. Buster was his own best gagman. He had judgment, taste; never overdid it, and never offended. He knew what was right for him.”

Clyde Bruckman paused, lit a cigarette, and went on. “You seldom saw his name in the story credits. But I can tell you — and so could Jean Havez if he were alive — that those wonderful stories were ninety percent Buster’s. I was often ashamed to take the money, much less the credit. I would say so.

“Bus would say, ‘Stick, I need a left fielder,’ and laugh. But he never left you in left field. We were all overpaid from the strict creative point of view. Most of the direction was his, as Eddie Cline will tell you. Keaton could have graduated into a top director — of any kind of picture, short or long, high or low, sad or funny or both — if Hollywood hadn’t pushed him down and then said ‘Look how Keaton has slipped!’

“Comedian, gagman, writer, director — then add technical innovator. Camera work. Look at his pictures to see beautiful shots, wide pans and long shots, unexpected close-ups, and angles that were all new when he thought them up. But each and every camera angle calculated to help tell the story — without sound, remember, and with damn few subtitles.”

“...The guy’s honesty was impressive. He wouldn’t fool his audience. None of the easy camera tricks like cutting an action into several parts with a new camera angle for each, then splicing it all together.... When he did use a camera trick, he did it deliberately, to make an impossible statement. Like multiple exposure. Not double exposure, which is a picture on top of a picture, generally an amateur accident. Multiple exposure is dividing up the picture frame into parts, taping the lens to correspond, and photographing each part separately. Keaton didn’t originate this idea. It had been used for years to show an actor in two roles at once. But it was a difficult technique. It was hard to join the halves of the picture without a telltale line down the middle. It was also hard to get the separate actions to synchronize — like looking up at the exact moment that your alter ego, in the earlier exposure, said something to you.

|

“Buster Keaton did the multiple exposure to end all multiple exposures. It was in Playhouse. He did an entire minstrel show all by himself — nine Busters in blackface on the stage at once. Every move, song, and dance exactly in unison. That meant taping off the lens into nine equal segments accurate to the ten-thousandth of an inch.

“‘It can’t be done,’ said [Elgin] Lessley, the cameraman.

“‘Sure it can,’ said Buster. ‘We won’t use tape.’

“He built a lightproof black box, about a foot square, that fitted over the camera. The crank came out the side through an insulated slot. It was in the front that the business was: nine shutters from right to left, fitted so tight you could have worked underwater. You opened one at a time, shot that section, closed that shutter, rolled the film back, opened the next shutter and shot, and so on.

“‘Keep this a secret, you lugs,’ said Buster. We did. Hollywood gave up on that one. No one even tried to copy it.”

Clyde Bruckman stamped out his cigarette. “I often wish,” he said, “that I were back there, with Buster and the gang, in that Hollywood. But I don’t have the lamp to rub. It was one of a kind.”

Lieutenant William Pittenger

William Pittenger

(31 January 1840 – 24 April 1904)

is known for

Daring and Suffering: A History of the Great Railroad Adventure

(Philadelphia: J. W. Daughaday, Publisher, 1863),

his terrifying first-hand account of the now-famous Union attempt

to steal a Confederate railway engine and run it north,

destroying cables, tracks, and bridges along the way.

The attempt was an almost instant failure.

Union soldiers under the leadership of a secret agent named

James J. Andrews

boarded a Confederate train as civilian passengers,

stole it during a meal break, ran it a few miles north,

and pulled over to a side track to allow a scheduled Confederate train to pass in the other direction.

To their surprise, the other train had a flag on its engine,

indicating that a second train would be following in a while.

Worse, the second train also had a flag on its engine,

indicating that yet a third train would follow.

This unexpected complication forced Andrews and his men to abandon the mission and flee.

They were hunted down by bloodhounds,

and the bulk of the book is devoted to the harrowing tales of how the men were imprisoned and horrifyingly treated,

and how eight of them were executed.

The Kennesaw Civil War Museum has a massive display concerning the Andrews Raid,

including the stolen locomotive.

See their web pages at

http://roadsidegeorgia.com/site/kcwm.html

and

http://ngeorgia.com/history/raiders.html.

http://roadsidegeorgia.com/site/kcwm.html

and

http://ngeorgia.com/history/raiders.html.