Something Big about It |

|

Jim Curtis, in his new book, Buster Keaton: A Filmmaker’s Life (NY: Alfred A. Knopf, 2022, p. 285),

details something I never knew before.

When producer Joe Schenck moved to United Artists and

moved distribution of Buster Keaton’s future pictures there as well,

he was concerned to assemble “the most prestigious roster of talent.”

Says Curtis, “In terms of a picture, all they [United Artists] had from Keaton was a title, and he was

encouraged to make it something special,”

and therefore, I infer, something expensive.

Said Schenck about future UA productions,

“Each picture must have something big about it.”

The General began preproduction in the spring,

it began shooting in June,

and before he completed the final edit, no later than November,

Buster would be punished for having made “something big about it.”

|

|

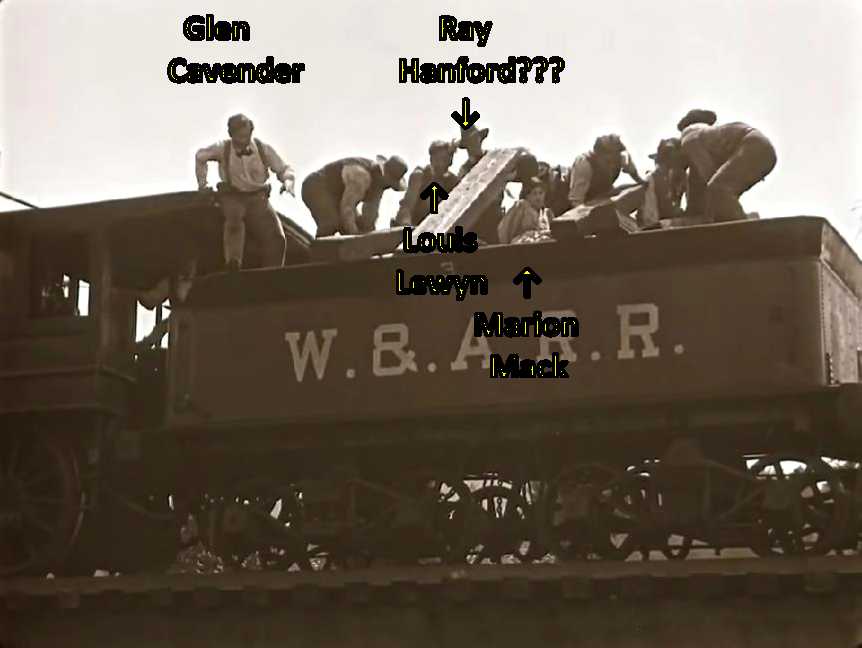

Joanna Rapf, in Buster Keaton: A Bio-Bibliography, page 23,

claims that Louis Lewyn was one of the backers of the production

and was the reason why his wife, Marion Mack, was cast as the leading lady.

Is that true? Does anybody know? Help?

|

|

Buster was also careful not to make a straight comedy — or a straight adventure,

or a straight drama, or a straight war story, or a straight chase film.

Those elements are all there, but they serve to support mood, texture, atmosphere.

The theme of the story is professionalism.

The film conveys a sense of reverence for the recent American past,

a reverence of

|

Costume Tests |

|

Buster began to let his hair grow over his ears and out at the back

in honor of William A. Fuller. These photos are all by Melbourne Spurr, Hollywood. |

|

(Margaret Herrick Library still # 133) |

|

|

|

NEWS FLASH! (18 June 2014): We just might be able to work out everyone’s particular contribution,

because there were recently two major discoveries, and I mean major:

Never-before-seen photographs and a copy of an annotated script for Buster Keaton’s masterpiece The General.

Until I can see these with my own eyes, I can know nothing.

Well, almost nothing.

It turns out that the script

was merely an anonymous staffer’s submission to the trustees of Buster Keaton Productions

and to UA, as part of the routine process of getting financing.

It may even have been used as an estimating script, though that is rather doubtful.

Buster and his crew never referred to the script during the shoot.

A grand total of one page of this script has now been published,

and so we can see that this was written only as a prerequisite to financing.

The accounting department was not about to throw half a million dollars

on a project that did not even have a business plan.

It was not a true shooting script.

We’ll take a look at that page shortly.

|

|

Oh. Buster Keaton Productions. Ugh.

Sorry. I didn’t explain.

You would think from the name of the firm that it was owned and operated by Buster Keaton.

It was not.

Let’s look at Jim Curtis’s book (p. 205) to learn a little bit:

|

|

...the principal stockholders

were the two Schenck brothers, who jointly owned 40 percent of the corporation,

followed by Loew’s Incorporated treasurer David Bernstein, Irving

Berlin, Sophye Anger, Lillian S. Ullman, David L. and Arthur M. Loew

(the sons of Marcus Loew), production executive Albert A. Kaufman, and

attorney Leopold Friedman. No apparent effort was made to make Buster

Keaton an owner of Buster Keaton Productions....

|

|

So, there you go.

This was a disaster in the making.

Whether the trustees had any nefarious intentions, we do not know and probably can never know.

Nonetheless, by not inviting Buster to be part of the firm,

they were all setting themselves up for a disaster,

and Buster should have understood that, but he was too trusting, far too trusting.

Metro, later MGM, was a subsidiary of Loew’s, and so it is interesting (read: disturbing)

that Joe & Nick Schenck, Bernstein, the Loew boys, and Friedman were all executives at Loew’s.

Kaufman, part of the Zukor clan, was with Paramount, and so was Sophye Anger

(Lou’s wife).

Irving Berlin was Joe Schenck’s best friend.

Lillian S. Ullman remains our mystery gal.

In essence, this “independent” production company was run by executives of Hollywood studios.

So, how independent was it, really?

It put on a show of being independent for a few years, and it kinda sorta acted like an indy for a few years,

but it wasn’t meant to last.

It was a façade, a charade.

By the way, Leopold Friedman is identified simply as an attorney.

Maybe a little more background should be added:

He was

the head of the legal department for Loew’s, Inc..

That adds a little more perspective, yes?

|

|

and, for whatever it’s worth,

The Times Union, Albany, NY,

Friday, 27 October 1939, p. 10;

Showmen’s Trade Review,

24 November 1945, p. 9;

Sunday Star-Ledger, Newark, NJ,

Sunday, 6 April 1947,

Oh wait wait wait. Bingo Crosbyana.

I found him!

Born 10 June 1887 in Kodez, Germany. Parents: Abraham and Rosalie.

LL.B. New York Law School.

Executive at Loew’s in 1915, became General Counsel in 1921.

Served in the military (Navy): 4 Dec 1918.

Wife: Ruth Harriet Mahoney aka Ruth Harriet Holyman, born March 1900.

Marriage certificate number 15580.

Marriage certificate witnessed by David H. Holyman and Sigmund Friedman.

Residence in 1940: 65 W 54th St [Warwick Hotel], Manhattan.

Sister: Helen (09 Jul 1880, Germany – 1967).

Brother: Sigmund (Dec 1883 – ????).

Sister: Martha (Feb 1885 – ????).

Helen’s daughter: Amelia (14 Jan 1907 – 15 Feb 1990).

Helen’s son: Donald (18 Feb 1911 – 13 Apr 1986).

He passed away sometime around 1980. Still no death date or obituary, though, and heirs remain unknown.

Oh, wait. Never mind.

He passed away on 18 December 1978.

You’ll see his obituary below.

|

|

Enough of that. Back to the script:

|

|

As you can see, this was adapted from the conversations among the members of Buster’s gag department.

A witness was probably sitting off to the side and scribbling shorthand notes.

This “script” contains some ideas that were used in different scenes in the movie, and in different ways.

Overall, though, it has remarkably little to do with the movie.

I wonder if it was

Al Boasberg who was primarily responsible for the notes that evolved into this “script.”

Joe Schenck had hired Boasberg (a Buffalo boy!

Dewey Michaels’s brother-in-law!) to work in the gag department,

but he was a verbal comic, not a visual comic.

He was entirely out of his element and contributed nothing.

All he ended up doing was writing a few of the title cards.

Maybe he helped type the “script,” too.

This “script,” though it is not a document that Buster or his crew used in any meaningful way,

is nonetheless of major importance,

because this is the sort of paper trail we have never had access to before.

|

|

Actually, I strongly suspect that Buster’s previous movies didn’t have even a draft script for the accountants.

They probably just had a one-page proposal typed up by a secretary on staff.

The reason for a full-length draft script for The General?

United Artists probably demanded it as part of its agreement for taking on distribution duties.

If Buster ever saw this script, he likely did not read it or even open the cover.

|

|

As far as I know, these photographs and this script, despite promises, were never published after all,

and so there is nothing I can say about them.

Kendra Preston Leonard’s blog post,

“The Paratexts of Buster Keaton’s The General (1927),” includes

a photo by Basil Wolverton showing Buster on location, between scenes.

I suppose this is from the

cache of photos announced in 2014, but I do not know for certain.

|

Special Effects |

|

If you notice all this on a first viewing, there’s something wrong with you.

If you still don’t notice on a third viewing, there’s something wrong with you.

Here are a few simple special effects:

|

|

|

The sentry is real.

The nearby tents are real.

The two soldiers by the campfire further in the distance are real.

The mountains, the sky, the moon, and the tents stretching out to the distance are all a painting.

I cannot be sure, but I assume this was a glass shot, and it was most likely filmed outdoors, on location.

|

|

|

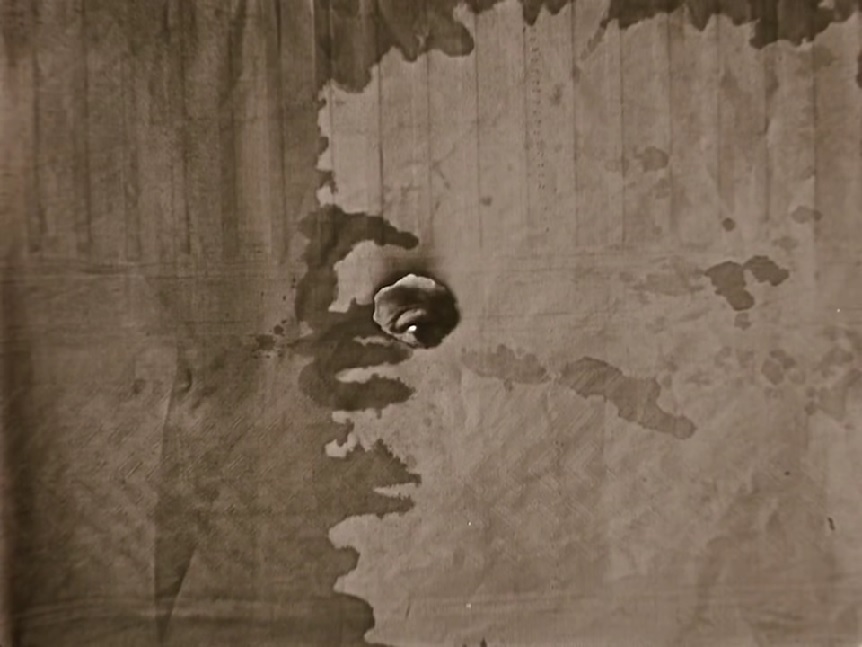

Above is not a special effect. I initially thought it was. I was wrong.

This really was a shot through a hole in the tablecloth revealing Johnnie’s eye looking through.

|

|

|

On the other hand, the above really is a special effect.

Specifically, it is a double exposure.

The tablecloth, stiff and solid as a rock, was taken first, with the center blocked.

The camera operator then blocked the lens, ran the film backwards to the starting point, slipped in the reverse mask,

and exposed again, this time revealing Annabelle.

This image was surely shot with a single camera, perhaps with a special-effects camera with pin registration.

The domestic and the export editions each surely got a different portion of this shot.

Look carefully, and you can see that the tablecloth and Annabelle weave through the gate differently,

since the pin registration was not quite perfect.

This shot was certainly taken at the 1025 Lillian Way studio when the company returned to Hollywood,

and it must have taken many hours or perhaps even days to set up.

|

|

Note the name plaque on Engine 8: COLUMBIA. |

|

|

These three shots were backwards and extremely overspeeded.

There was no other way to get the trains to behave as they needed to.

You can see the smoke getting sucked back into the stacks.

To film backwards, either the camera operators cranked ahead with the lenses blocked and then cranked backwards,

or they mounted the cameras upside-down, after which the film was spliced in upside-down again.

I do not know which technique was used here.

Oh. Wait. Yes, I do know which technique was used here:

The camera operators cranked ahead with the lenses blocked and then cranked backwards.

I’m certain of that.

|

|

Now, I’m thinking, even though I don’t like to.

They couldn’t do a Take Two.

They had to get it perfect first time.

How?

I am not a structural engineer,

but I can think a little bit, even though I don’t like to.

If I had to do this, I would want to test it a few times to make sure.

I would want to build and destroy the bridge at least twice over before going live.

I would want to run some heavily loaded boxcars over the bridge just to make sure they’d tilt towards the camera exactly the right way,

and that the bridge would give way at exactly the right time in exactly the right place.

I would want to film the trials with multiple cameras.

I would want structural engineers and explosives experts observing from all angles.

Wouldn’t you?

Is that what was done here?

Or did the crew have a better way of ensuring a perfectly choreographed calamity?

Since there were platforms on the river bed, aquatic life was probably at a minimum at the moment.

|

|

|

Behind the Scenes |

These three rare behind-the-scenes shots were listed on eBay circa 2001.

I so much wanted to bid on them, but my net total wealth was hovering somewhere around 22¢ at the time.

When three cops searched my apartment

in the hopes of finding something, anything, illegal,

they took the 3.5" disc that contained these images. Boy were they disappointed.

I was worried sick that I would never see the disc again, but my lawyer convinced them to return it, thank goodness.

So now, thanks to the lawyer, I can share these three images with all of you.

|

|

|

|

And now it’s movie time!

A hobbyist happened to have his 16mm camera with him and he captured just over a minute of the production.

Note how shy Buster was when posed with the cameraman’s wife.

He was helpless around strangers and just did not know how to have any confidence.

That was partly because he was painfully shy all his life,

and it was partly because he was hard of hearing,

as he had suffered a horrible ear infection in the military during his tour of France.

He had a lot of trouble understanding some people,

and perhaps he couldn’t make out a syllable of what the cameraman and his wife were saying to him.

The video transfer is terribly overspeeded, and so hover your mouse over the image, click on the gear icon,

and set the playback speed to 0.75. That will help.

Take a look:

|

|

Now, compare Buster’s comportment above with Buster’s comportment when he is with his trusted colleagues,

on his own turf, in full charge.

Below is a recently unearthed behind-the-scenes photograph taken by Basil Wolverton.

We see that Buster exuded confidence.

|

|

Here’s another little something I just bumped into, posted by John Bengston on

Silentology. Click on

Silentology to find a bunch more.

|

|

Here are some photos I just found on Flickr.

For fear that they will vanish, I copy them all here.

I did not ask permission, because I am unable to figure out who posted them.

|

|

This is from the beginning of the production, surely the first week.

All the extras are in position, but in the rear,

a stagehand is pulling up the ladder onto the second-story balcony of the Town Hall,

or perhaps lowering it down.

Why? Look at the roof!

The town crier is standing atop, by the ventilating cupola.

In the final film, the town crier would not be quite that high.

He would cry out animatedly from the second-story balcony.

Another stagehand, on the ground, is holding another large implement of some sort.

If you could arrange with your travel agent to visit 1926 Cottage Grove,

could you do us the kindness of asking these people what this scene was about?

|

|

Here we get an idea of how large the crew was.

We’ll never be able to identify these people, alas.

|

|

Oh my goodness gracious me!

I keep forgetting about this one.

Zo, 21 years after first posting this page, here it is!

Here we have the restaurant set in or near Cottage Grove,

with Roscoe Arbuckle behind the counter.

This, I am certain, is not a gag photo.

Roscoe really was serving as bartender to cast and crew.

The customers are Joe Keaton, in everyday clothes,

Tom Nawn, in everyday clothes,

and Buster, still made up as Johnnie Gray!

This shot was taken in the middle of a day when Buster was on camera but when Joe and Tom had no scenes to shoot.

Now, Buster and Roscoe were completely loyal to one another.

Roscoe had given Buster his start in movies

and he was thrilled to have Buster outshine him on screen.

Because of that abominable scandal (Roscoe was entirely innocent!),

Roscoe was seldom allowed on screen and generally had to work under a pseudonym,

though sometimes he forewent any credits at all.

Many are in agreement that Roscoe contributed ideas

to all eight of Buster’s movies from 1924 through 1927,

and I am quite convinced he contributed ideas to The General.

This restaurant/bar set was certainly built in or near Cottage Grove, not in Hollywood.

Why do I say that?

Because Buster was trying out different story ideas simultaneously on exteriors and interiors,

changing his mind constantly,

and he obviously had access to the Texas engine at the time, because he was improvising on that simultaneously.

Roscoe was in Cottage Grove certainly to help out in some capacity.

My guess is that he and Buster were tossing story ideas back and forth.

|

|

No, Roscoe did not direct all of Buster’s movies in those intervening few years, but he was frequently around.

His precise contributions?

We do not know, but he was definitely a primary creative force on The Frozen North.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

The story in the film,

apart from the initial idea of Union soldiers stealing a train and sabotaging the lines

and a Southern crewmember giving chase,

was a work of pure fiction, but it was fiction that had the look of authenticity.

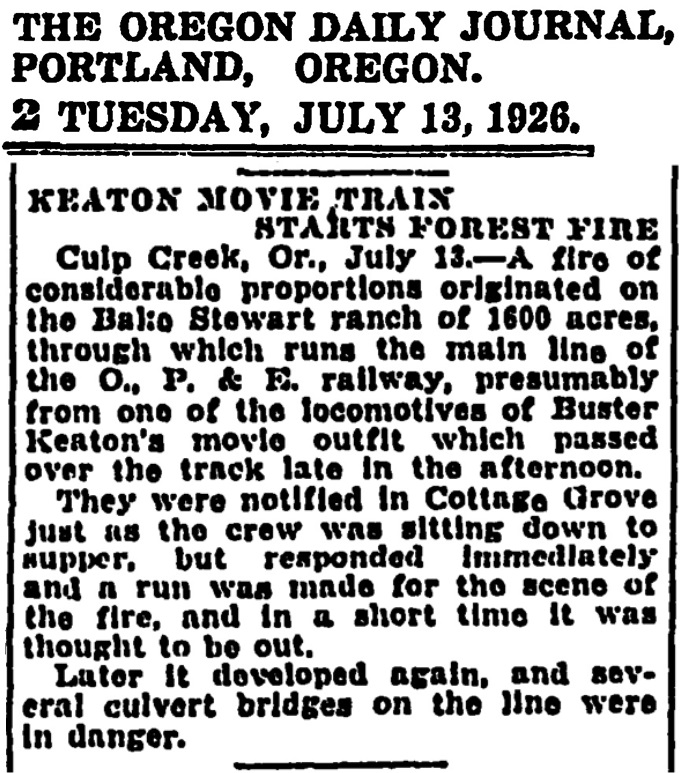

Shooting began on 8 June.

Keaton recalled a conversation:

|

|

“Now work fast.

Telephone the governor up there and you can get the whole damned Oregon State Guard for the war scenes.”

“Well,” the governor said, “I don’t know.”

He hesitated.

“We have two regiments going into camp in two weeks.”

“We’ll pay them a salary on top of yours,” said Buster.

“All right, they’re yours.”

|

|

Buster Keaton was the most popular star in Russia in the 1920’s.

Unfortunately, Buster never got a penny from that popularity.

There was no copyright treaty between the US and the USSR at the time,

and so the Eastern-bloc countries just duped European release prints —

and did the worst possible job of it.

The results onscreen were nearly unwatchable.

Here are two posters designed by the

Stenberg brothers for the 1929 Sovkino release of The General.

Note the predictable error.

There is no equivalent of the English H sound in Russian.

The Russian letter Н is the same sound as the English letter N.

So, when the Stenberg Brothers attempted to render

БЕСТЕР КИТОН back into English,

they goofed and made it BUSTER KEATOH.

If you know where to find a 1929 Soviet print of Генерал,

please give me a holler. Thanks!

|

|

Previous Keaton features had been released through Metro and its successor, MGM.

Since Joe Schenck had just switched jobs,

The General was the first of Keaton’s films to be released through United Artists,

a far less wealthy outfit.

This may have been a source of later problems,

for The General was to be the most expensive of Keaton’s features.

The original budget was somewhere around half a million dollars,

and that is pretty much what the full production cost proved to be.

|

|

|

|

The above newspaper article confuses me terribly.

It says that nearly all the uniforms were ruined and that replacements would need to be ordered from Los Ángeles.

The fire was on Saturday towards the close of the workday,

and Buster and the National Guard spent pretty much the entire night fighting the flames.

Yet what happened the very next morning?

The National Guard dressed in their uniforms and filmed the scene of the Southern army retreating from Chattanooga

and General Parker’s victorious Northern army advancing.

The replacement uniforms could not possibly have arrived that quickly!

Monday was the scene of the Confederate troops returning to Marietta after the battle at Rock River.

Tuesday was the scene of the Confederate troops rushing down Main Street Marietta towards the impending attack at Rock River.

On Wednesday the National Guardsmen were dismissed and the O.A.C. students and their mounts were sent back to their campus by train.

Zo, I don’t think too many uniforms were damaged,

nor do I think that the Guardsmen and O.A.C. students needed to be kept on an extra few days.

|

Buster with the California National Guard, receiving a commission from Oregon Governor Patterson on behalf of the Oregon National Guard. |

|

|

Accidents, Injuries, and Insurance |

|

July 1926 gave Cottage Grove a record heat wave.

The locomotives had been equipped with

spark arresters and a crew was always on hand to smother any flames.

Nonetheless, sparks from the engines set haystacks alight, and the film crew, armed at all times with fire-fighting equipment,

was smothering the fires as quickly as the engines started them.

They had to pay the farmers for the burned haystacks, of course.

|

|

Marion Mack recalled a fire in an interview conducted by Gregg Rickman

(“Marion Mack 30 Years Later,” Cobblestone: The Magazine of All the Arts vol. 3 no. 27, Summer 1977, p. 24):

“You remember when they set

the boxcar on fire? That started a forest

fire. It was pretty bad. We had to stop

shooting for a few days.”

Odd. Could be right.

The boxcar was set alight on Wednesday, 23 June 1926,

and the next documented shooting was on Saturday, 26 June 1926.

The boxcar was burned (again) the following day, Sunday, 27 June 1926.

Without more detailed documentation, though, I cannot pursue this further.

|

|

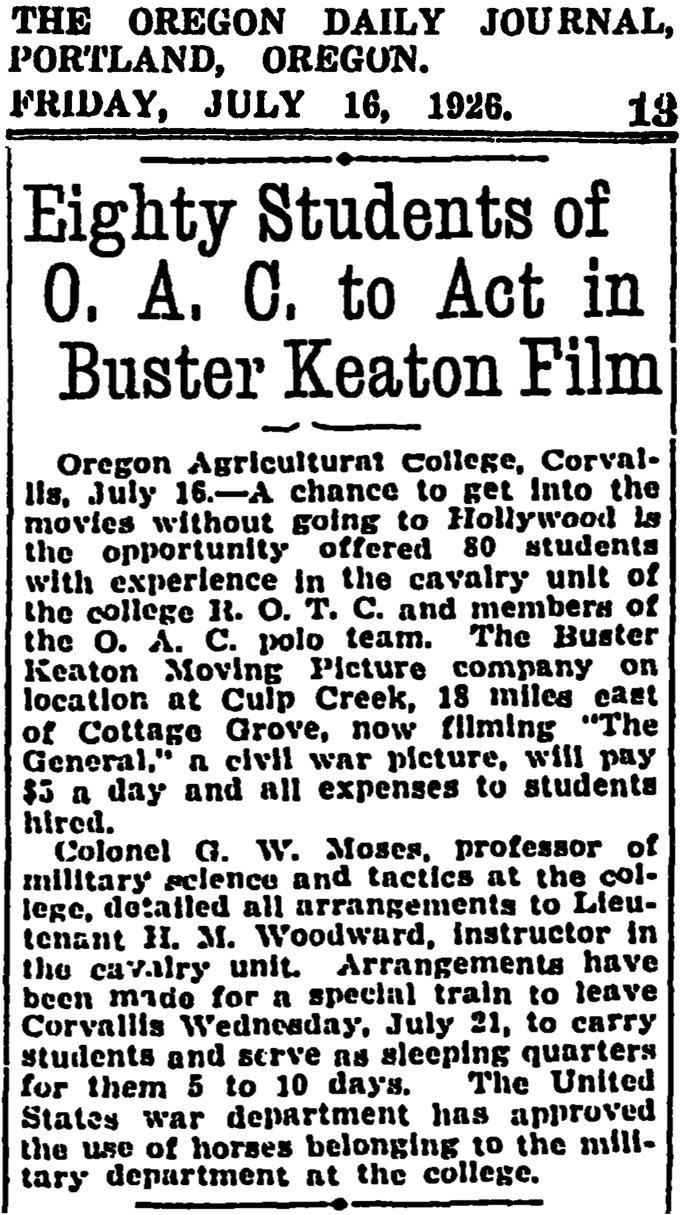

There was one fire that may or may not have been caused by the locomotives.

It was noticed after close of workday and it was put out that night:

|

|

|

The only massive fire was not the fault of the film crew,

as it began towards the end of a day long after the locomotives had ceased operation.

The entire company dashed off, with its equipment, to put out the blazes.

The timing was fortunate, as the bulk of the filming had just wrapped,

and the hundreds of extras, who consisted largely of the Oregon State Guard,

now doubling as fire fighters, were about to be dismissed anyway,

as their work in front of the cameras was largely done.

Keaton himself led the

|

|

Just about the only filming that remained consisted of pickups,

but the forest fire put a pause to some of that remaining filming, as the smoke in the air would cause mismatched shots.

That was not a serious problem and the solution was simply to wait for a few days.

Then there was another fire, of unknown origin,

that destroyed Goff’s Stove Hospital and Second Hand Store on South River Road on the night of 4 August 1926.

The smoke was now thick and would produce mismatched shots.

The heavy smoke lingered in the sky, and so the company left for Hollywood to shoot interiors,

namely the parlor of the Lee household, the inside of the railroad car on its way to Big Shanty,

the Union rendezvous at night.

Several outdoor scenes were also now created in the back lot:

the forest where Johnnie ditches his costume and gets caught in a downpour,

the escape back into the rainstorm.

A month later, Cottage Grove had a rain, and the troupe returned for the final pickups.

Altogether, the delay hardly added a penny to the budget, since the Guard and the extras had by then already been sent home.

|

|

While back in Hollywood, MGM hosted a party at the Hearst Castle.

Joanna Rapf has some info about this in her book, Buster Keaton: A Bio-Bibliography

(Westport, CT: Greenwood Press, 1995), which I confess I’ve not read.

Here is a photograph:

|

|

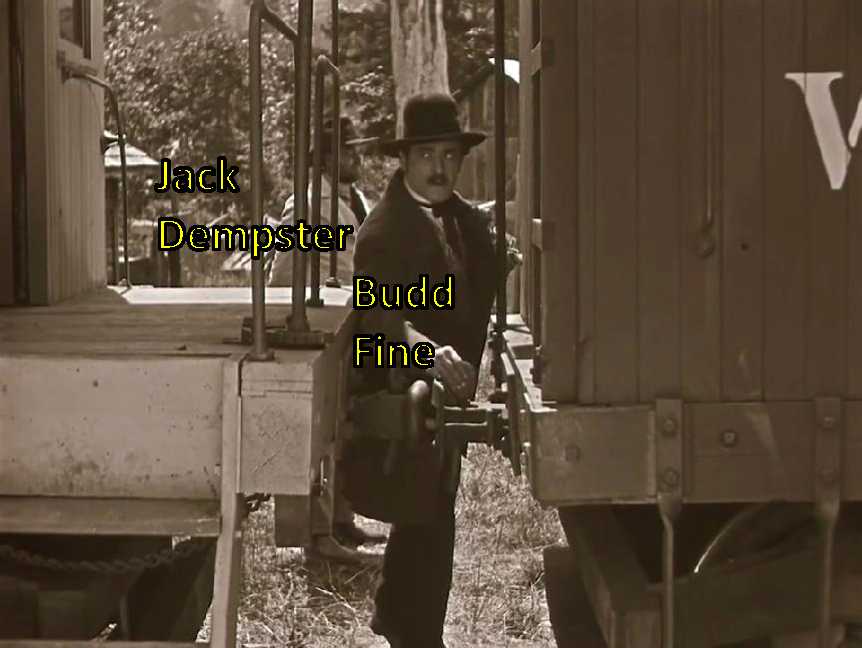

Joanna Rapf identifies most of these people,

and so above I just ripped her off.

|

|

Admittedly, I do not have the financial records, and the published figures vary wildly,

from a total cost of about $300,000 up to a total cost of somewhat over $900,000.

My best guess, derived from nothing other than agonizing over the conflicting

|

|

There were a few other problems too.

An actor portraying a soldier accidentally discharged his rifle as Harry Barnes was walking right in front of him.

Several Guardsmen received minor injuries during the battle scenes.

One Guardsman was even knocked unconscious by an explosion.

I have no details about any of these specific incidents, and so I do not know where to assign blame.

To the best of my knowledge, Buster had received a few injuries on a few previous films, but nobody else had.

He tried always to run a safe operation,

and for The General he hired the top experts to plan and execute the battle scenes.

Despite all precautions, now, for the first and only time in his career, Buster was dealing with multiple injuries,

all concerning extras, and once dealing with obsolete equipment.

Soldiers who were designated to fall in battle noticed, to their fright,

that they were off their marks and were lying nearly atop explosive charges that were set to go off.

There was nothing to worry about, though, since the explosions looked fearsome

but released nothing more than bursts of harmless smoke and would have caused no injuries.

They scrambled away quickly, even though there was no danger.

Explosive expert Jack Little made an error and set too much powder in a cannon.

That was probably the railroad cannon.

Buster was knocked unconscious when he was too close to that cannon as it fired.

I have no details and cannot even picture the problem.

In the scene when the troupes return from the battle, an extra named James Walsh fractured his hand in a cannon’s carriage wheel.

Again, I cannot even picture how that could happen; I would need more details.

In July, Fred A. Lowry sued Buster Keaton Productions for $2,900 for a crushed foot.

“Lowry says he was employed as a brakeman on the train

and the accident occurred because of lack of safety appliances on the cars,

which were made to appear like the cars used in Civil War days.

He says in his complaint that the drawhead of a car buckled

as he was attempting to couple two cars together

and in trying to get out from between them his foot was caught beneath a wheel and was run over.”

See The Cottage Grove Sentinel, 19 July 1926.

I assume this was settled out of court.

Apparently, the modern

|

|

I would love to learn more about Fred A. Lowry.

I see from

Ancestry.com that there was a Frederick Alton Lowry, Senior, born on 2 December 1878,

died 20 January 1956.

There was also his son, Frederick Alton Lowry, Junior, lifelong Oregonian,

born 23 March 1904, died 16 January 1967.

Both were dairy farmers.

Was one of these the victim of a buckled drawhead?

If so, why was a dairy farmer employed to couple obsolete railroad cars?

Does anybody know about these two gentlemen?

|

|

Unfortunately, the Sentinel also ran a poorly worded joke story

which might wrongly lead readers to think that ten members of Keaton’s cast drowned in the river.

I’m sorry such a joke article was ever published.

It was nearly a true story, though.

The crew explored Culp Creek and determined that it was only knee-deep.

As a precaution, a platform was built on the creek bed, but some extras wandered off the platform

and discovered, during the shoot, that there were some unexpectedly deep spots in the river bed.

Whether those spots had been missed during the exploratory tests or whether they were

|

|

There were seven stuntmen in the rising river when the dam broke.

It was shot partly in the McKenzie rapids, partly on Culp Creek.

The Raiders getting washed away by the rising water?

That was shot at the beach in Santa Mónica,

and the rising water was a breaker.

|

|

|

|

Thanks to the pathbreaking research of Kevin Brownlow,

we now know that the local newspapers confused the three principal engines.

In reality, an engine known affectionately to locals as

Old Four Spot

was remodeled into the General.

It had been manufactured less than two decades after the end of the Civil War by Cooke,

the same company that had manufactured the original Texas.

Another engine, the Yonah, was remodeled into the Texas.

A third engine was remodeled into the apocryphal Columbia.

The Yonah was old and tired, and Buster planned to give it a grand send-off.

But at the last moment it was discovered to be in better operating condition than

the engine that was impersonating the Columbia.

So, unbeknownst to the reporters, the Yonah/Texas and the Columbia were switched.

If you want to read more about this, with differing investigations and alternative conclusions,

here you go! Fascinating.

|

|

|

Wild Guesses —

|

|

Some of my guesses are undoubtedly wrong. This is my third attempt. My previous two attempts were much worse.

Let me know about any errors and I’ll fix them.

My copy of The Day Buster Smiled is in storage 800 miles away, and so I broke down and ordered another copy, which just arrived,

and which proved that I needed to make some fixes.

|

|

The biggest mystery, for me, is Ed Foster, whose name Kevin Brownlow gives as Edwin Foster.

The IMDb wrongly identifies him as Eddie Foster, who was much younger.

Our Edwin Foster had been a baseball player in Cleveland

(not to be confused with a later Cleveland baseball player, Edward Lee Foster).

After he retired, by about 1904 or thereabouts,

he and his wife Minnie were on the Keith circuit vaudeville

with an act that was a standard through about 1928, “A Volunteer Pianist.”

We see an advertisement in the North Platte Daily Telegraph of

Thursday, 2 July 1925, p. 6, that briefly describes their act:

“The ‘Volunteer Pianist’ is a comedy skit devoid of plot, the reason, however, is always furnished for the

many really funny bits introduced throughout the offering by these clever artists. The act consists of a combination of unusual piano playing, unique singing

specialties and a smart line of up to the minute patter. The opening discloses Minnie Foster explaining her reason for wishing she has a pianist. As she finishes,

Ed Foster appears in a rather nondescript makeup with his hands encased in an immense pair of mittens. Turning to this odd looking character, the

young woman asks him if he knew where she could secure a pianist. He replies by sitting down at the piano and without removing his mittens, play s a number

to show his ability. Finishing, Miss Foster starts removing his mittens and takes off his hands, twelve pairs of them. How he accomplishes his really superb

rendition of the selection is beyond comprehension.”

Ed and Minnie, who toured as Foster & Foster, had their picture on at least two issues of sheet music:

a circa-1904 issue of “I Wonder If You Miss Me (As I Miss You),” which seems to be on file at the

Cincinnati Digital Library, and a circa-1906 printing of “Bonnie Jean,”

which seems to be on file at the

UCLA Library Special Collections, Room A1713, Charles E. Young Research Library.

At the farewell dance at the Cottage Grove Lions Club on 28 July 1926,

when most of the cast and crew were packing up to return to California,

Ed Foster entertained by giving a piano recital while wearing multiple pairs of mittens.

The Cottage Grove Sentinel of the following day reported on this and explained that he portrayed the fireman on the Columbia.

There is so little footage of the Columbia, and it is taken from so far away,

that I can’t be completely sure that I am identifying him properly.

|

|

Another extra was James or Jimmy or Jimmie or Jimyi Bryant, a former boxer who switched to movies.

He had appeared uncredited in several Roscoe Arbuckle movies,

but for the life of me I can’t spot him in The General —

UNLESS he’s the engineer of the Columbia. Bet he is. Bet he is.

|

|

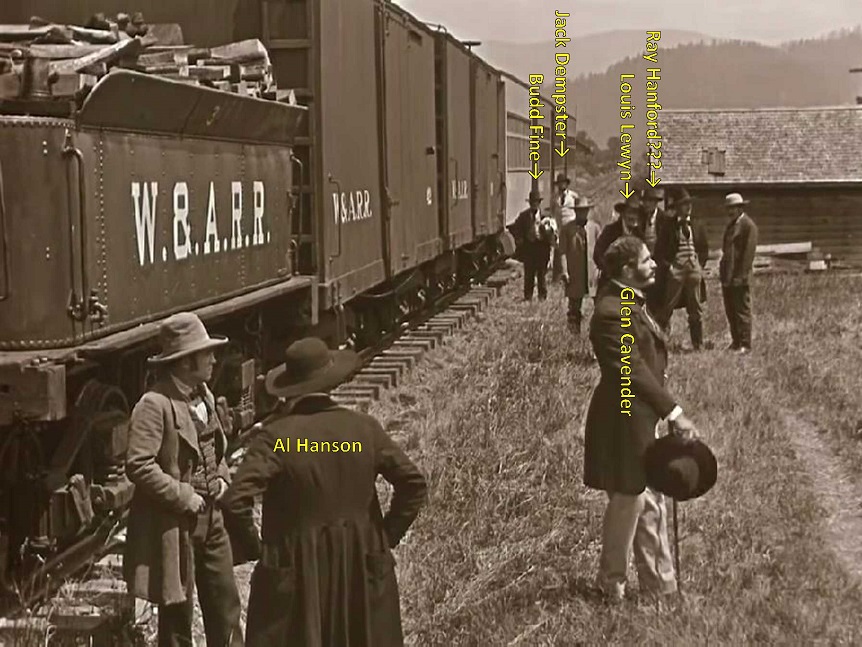

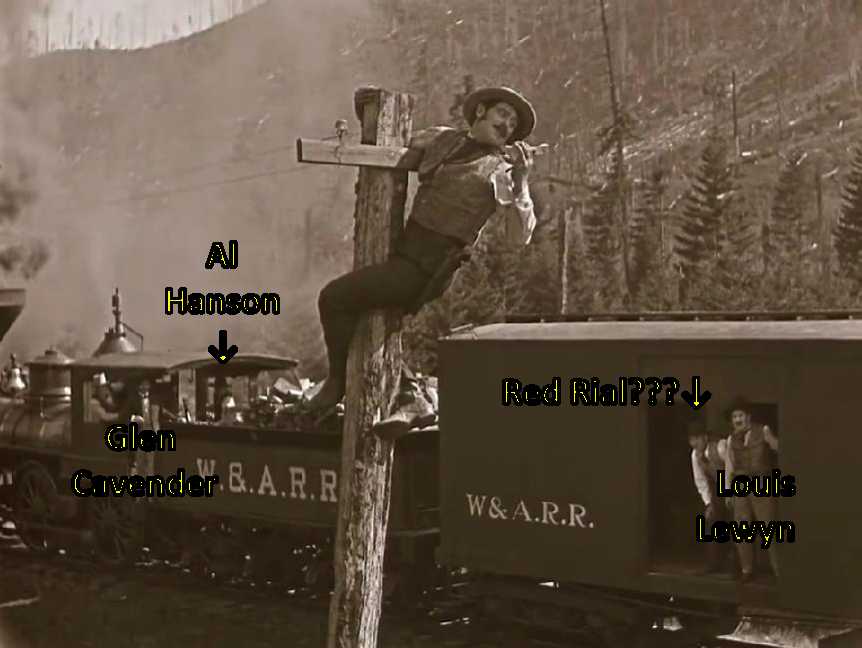

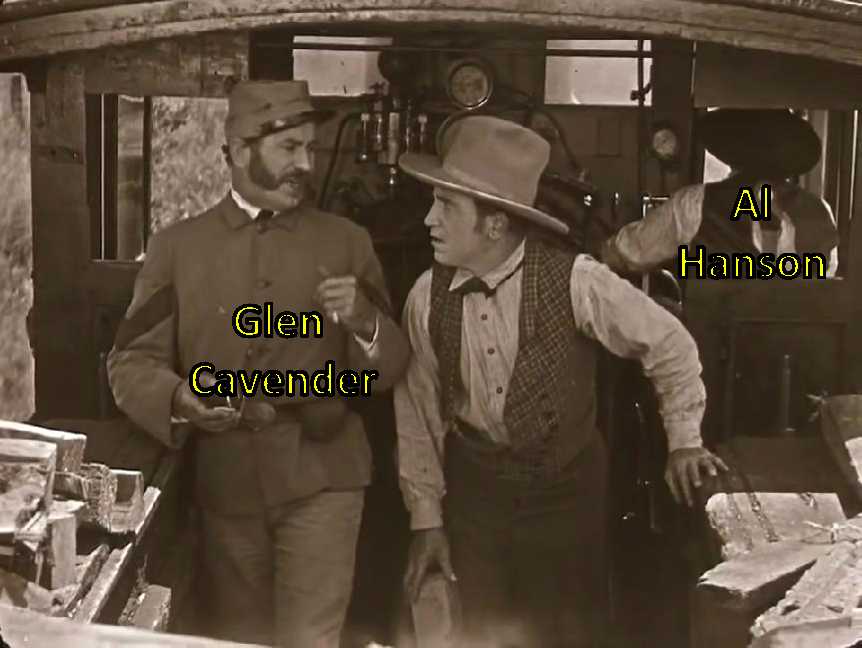

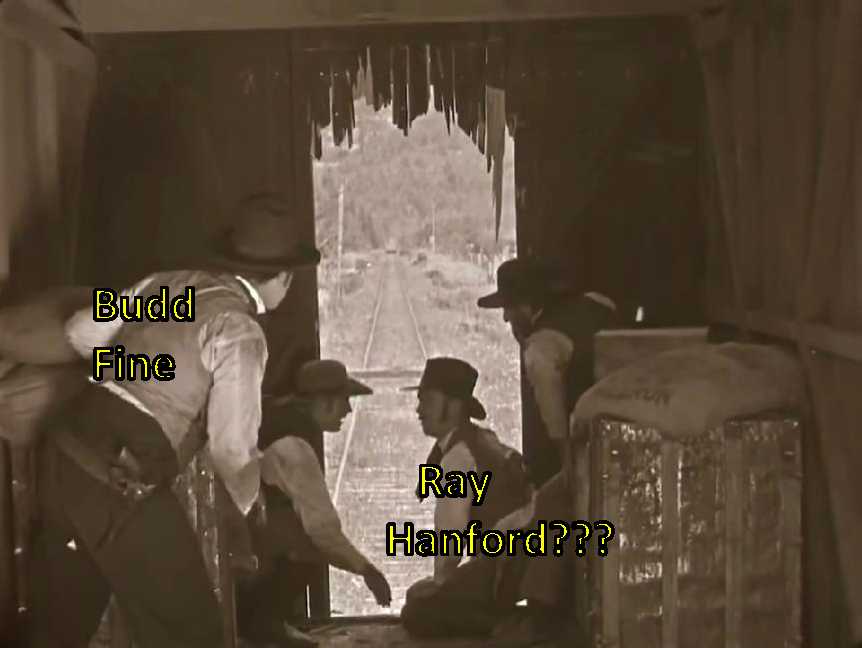

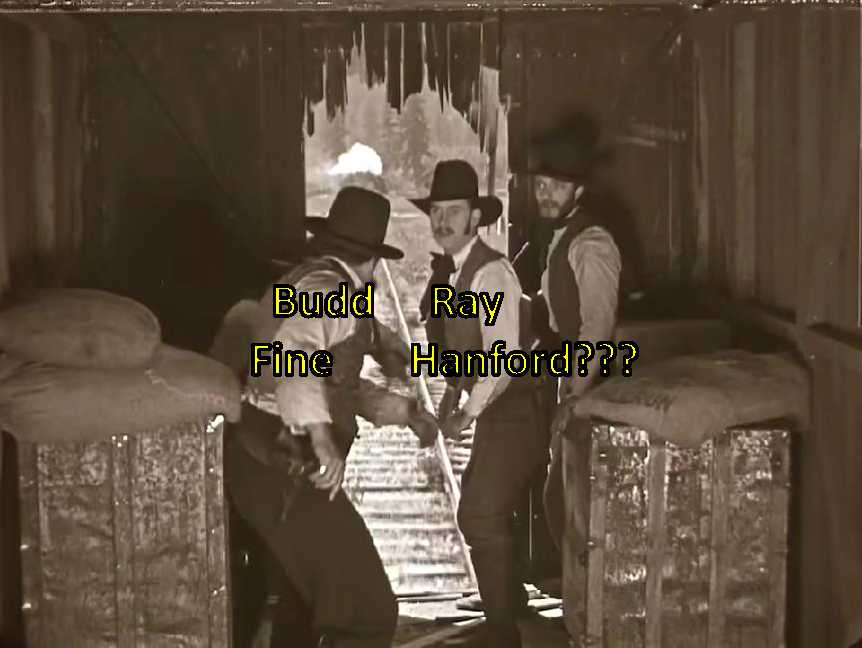

Another tidbit that had been nagging away at me for decades

was the knowledge that, somewhere in this movie, Marion Mack’s husband,

Louis Lewyn, portrayed a Northern soldier,

but I could never identify him.

Well, now I can. Hoorah.

As of now, here are my best guesses.

|

|

|

Do you notice something fascinating here?

The Raiders did not expect to find Annabelle on the train.

They cannot let her go, they cannot let her escape,

they need to imprison her but, lacking a cage or handcuffs, they bind her,

yet it is clear also that they will protect her.

She is unanticipated baggage, but she is now their responsibility, and they will keep her safe.

Soon they loosen some of the ropes.

We can see her lose her fear as she witnesses the raiders in action.

|