A Night with Charlie Chaplin

What on Earth Was That Movie, and Does It Still Exist?

The Saga of Fred Futter

What on Earth Was That Movie, and Does It Still Exist?

The Saga of Fred Futter

This image is posted at John McElwee, “Chaplin Heats Up For a 30’s Revive,”

Greenbriar Picture Shows, 12 April 2021.

How I would love to see this movie and hear its howling musical madhouse.

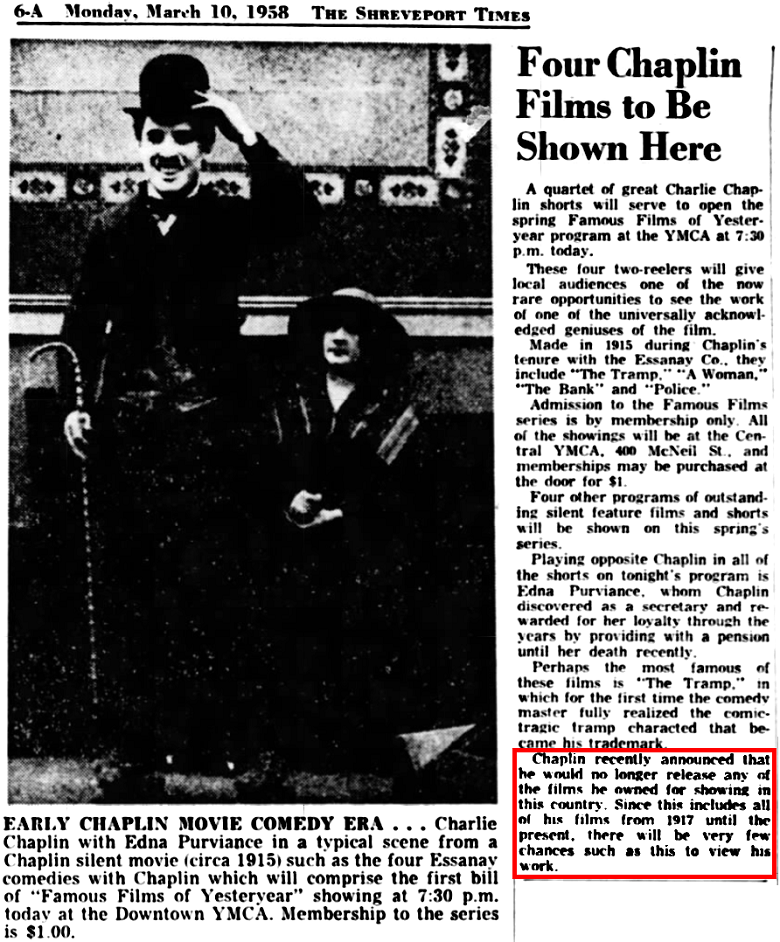

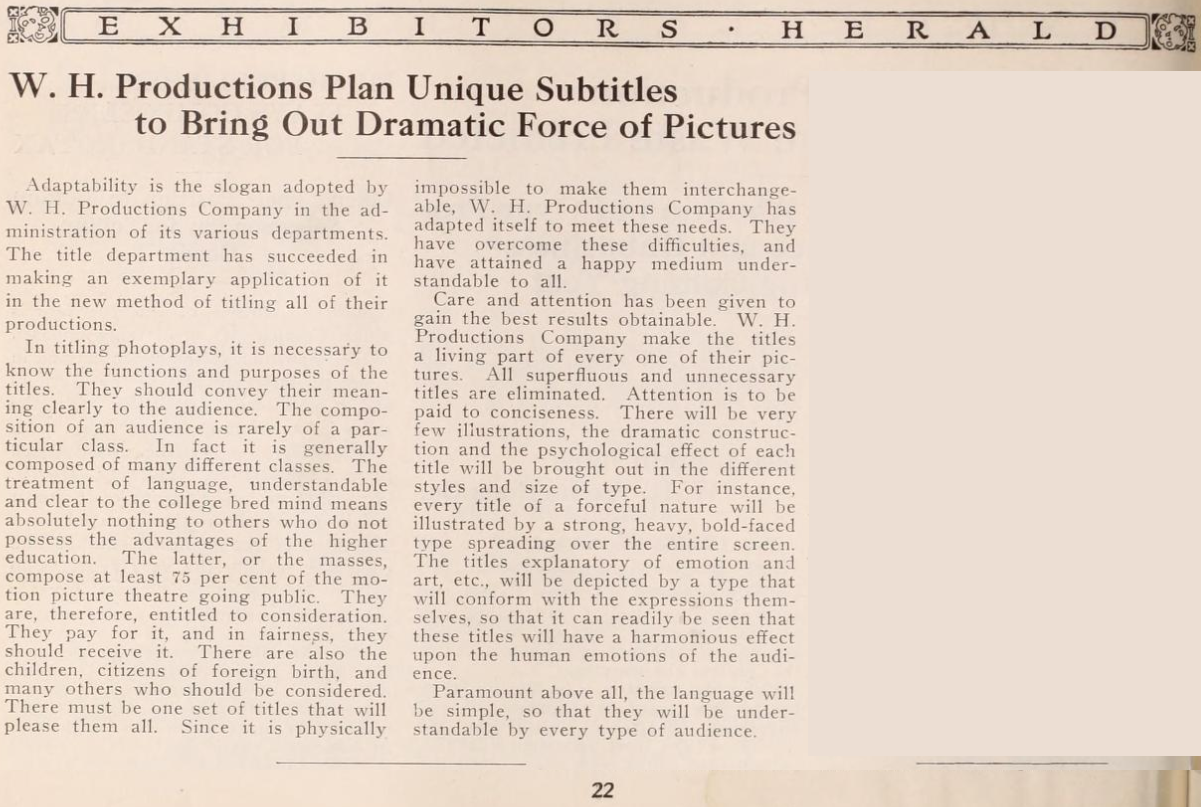

Before we can explore what A Night with Charlie Chaplin was, we need to get our bearings

by examining the various reissues of the films that Chaplin made during the first four years in the business.

Chaplin made some 40 or so movies from December 1913 through December 1914 for the

Keystone Film Company.

He was an actor for hire and had

no ownership

of those films and no control over them.

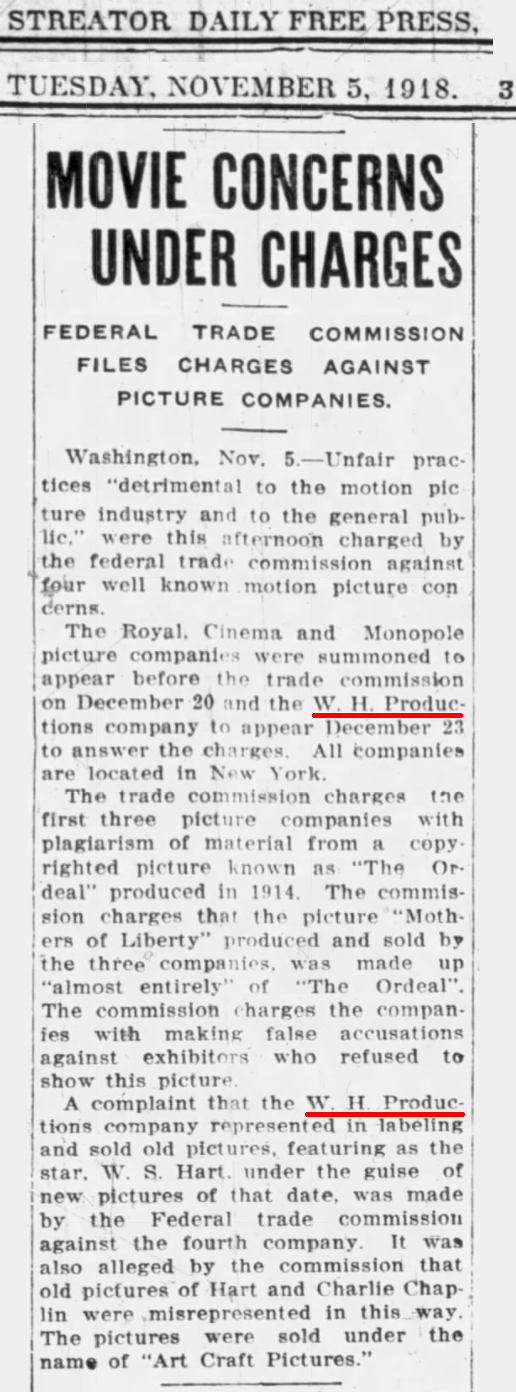

In about 1918, Keystone

sold 750 of its films to W. H. Productions Company of NYC,

which changed the titles, re-edited the films, and passed them off as new products.

W. H. seems to have taken its name from the initials of

William S. Hart, and indeed, it reissued Hart’s films as new products,

much to the irritation of Hart and much to the irritation of Hart’s fans,

who felt ripped off and who flooded Hart’s office with letters of complaint.

Another source has it that “W. H.” actually stood for

“Wonderful Hits.”

The two claims are not necessarily contradictory.

Below we shall see yet a third explanation for those two initials, a reversal of the initials of a cofounder, Hyman Wenick (or Winnik).

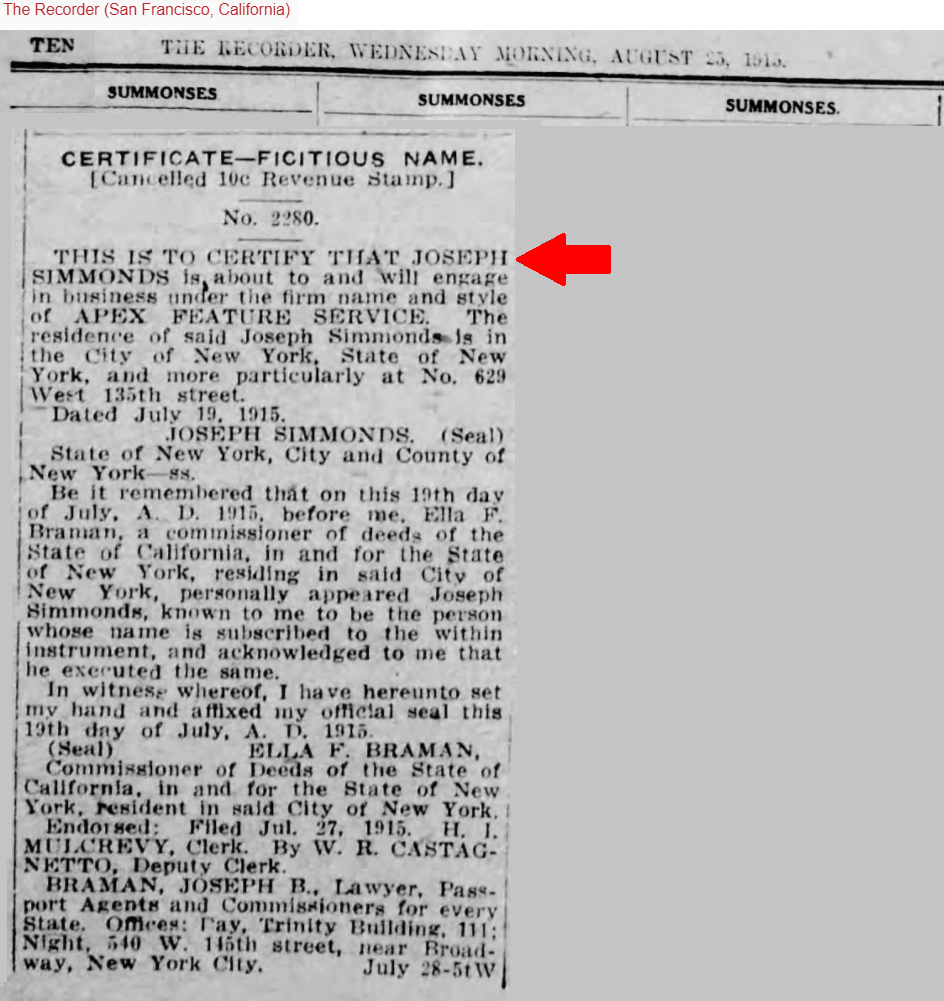

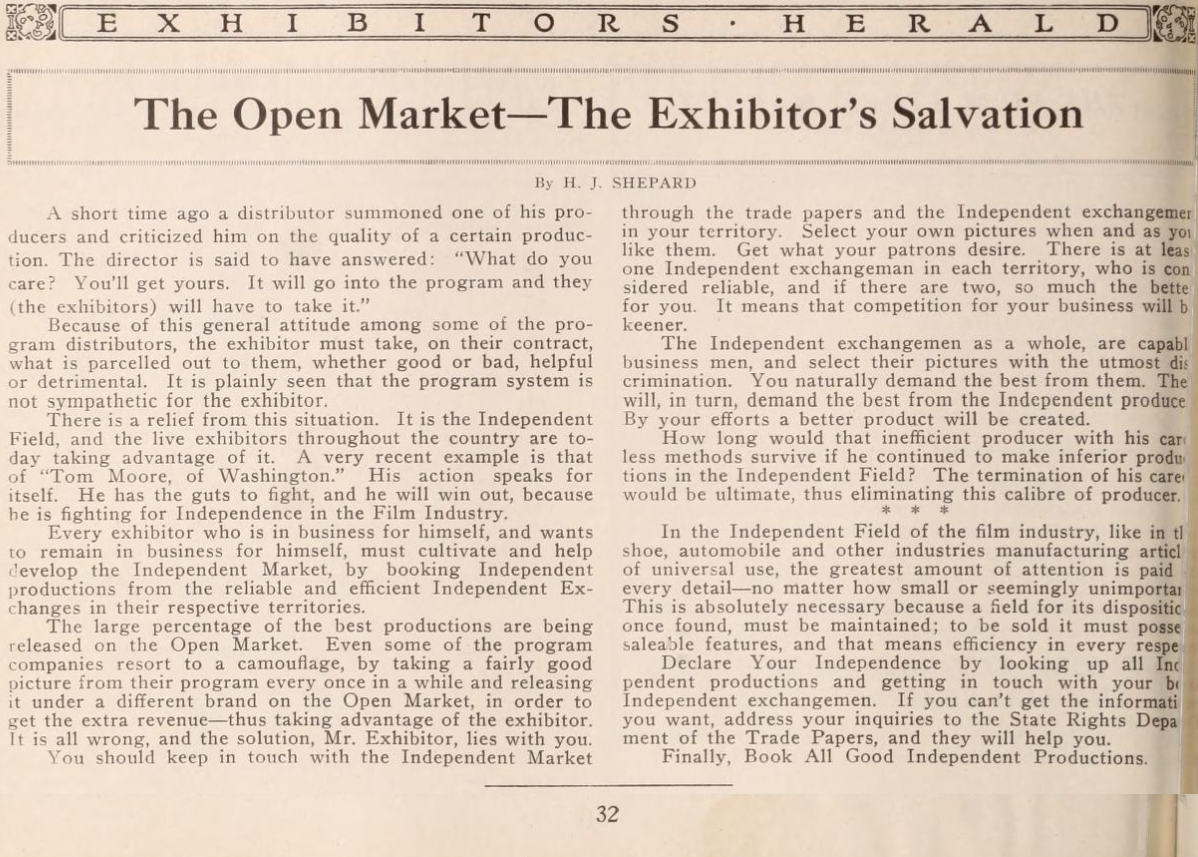

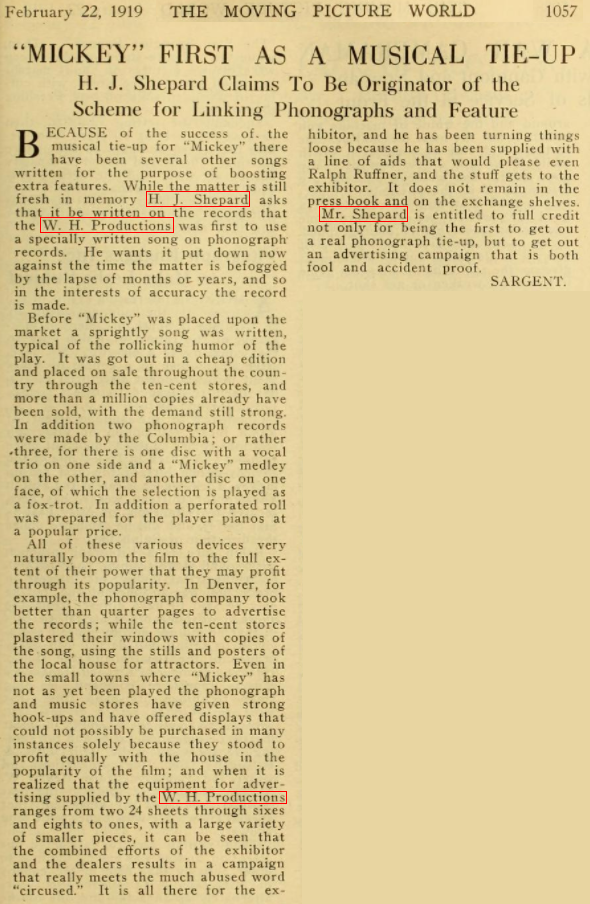

I just learned the names of two of the principals of W. H. —

Joseph H. Simmonds and Harry J. Shepard.

Okay, time to do preliminary searches.

I’m unable, yet, to find them on Ancestry.com, but I found a few news items that mention those two names.

Here they are.

Would you trust Simmonds with your business affairs?

I would never have known about this article had it not been for Paul O’Malley’s privately circulated paper,

“A Chronology of Film Exhibition in Denver,” 07 Dec 2014.

Variety vol. 54 no. 4, Friday, 21 March 1919, p. 51.

Okay all you genealogists out there:

Which Joseph H. Simmonds of NYC in 1919 had a brother-in-law named Hyman Wenick or Hyman Winnik?

I’m not having any luck with this puzzle.

(Ancestry.com search; Brockton MA City Directory 1910, p. 350; Brockton MA City Directory 1910, p. 372; The Brooklyn Daily Eagle, Sunday, 1 April 1917, p. 16; Hartford CT City Directory 1927, p. 1944; Find a Grave, 1968; The Philadelphia Inquirer, Monday, 7 October 1991, p. 6-BJ C.)

According to “Starts Thursday! The Art and History of Motion Picture Coming Attraction Slides,”

the owners of W. H. were

Harry and Roy Aitken,

who also co-owned Keystone/Triangle.

So the Keystone financiers were

competing against themselves, raiding their own company’s assets for their personal gain.

Why did I not see that coming? I should know better by now.

How long

W. H. Productions circulated those movies, I do not know, but

W. H. seems to have been shut down by the authorities in 1921 on account of massive financial fraud,

though its prints continued to circulate for a while, and I still find W. H. mentioned in newspaper ads as late as 1923.

Zo, let me do a quick batch of searches to see which W. H. editions of the Chaplin Keystones I can find on YouTube:

These all have something in common:

They are not original W. H. prints.

They are copies of copies of copies of copies of copies of copies.

They are all terribly cropped.

Some were wrongly transferred through the Academy aperture, resulting in the top, left, and bottom being lost.

(So many people who work in film and video

seem incapable of understanding that just because two images are the same ratio, it does not follow that they are the same size.

The know about Silent 1:1.33 and Sound 1:1.33 and assume they must be the same.

They are not the same. They are not even similar. Not even close.

I have foolishly engaged in arguments about this, with professionals.

It’s a lost cause.)

The music was added rather recently.

I love what Charlie said to Robert Musel about the copies of his movies that were broadcast on TV:

“I

don’t want to see those old shorts on television; they depress me.

I don’t like the cutting and the poor, scratchy old prints,”

London UPI story,

printed as “Charlie Chaplin at 83,” The Oakland Tribune,

vol. 98, no. 318, Sunday, 14 November 1971, Entertainment Week p. 9-EN.

More research needs to be done to trace down original prints or elements of the W. H. editions of the Keystone Chaplins.

The W. H. editions contain important material that is missing from other editions,

missing even from the recent restorations.

We know that the Keystone films were originally distributed by Mutual and then by W. H.

When the feds seized W. H., various

state-rights distribs retained their prints.

(Among these state-rights distributors were

Tower Film Corporation and Jans Producing Corporation.)

What happened to the camera negs after the closure of W. H., I wish I knew.

I suppose that the feds auctioned off the W. H. assets,

which would have allowed distributors and pretty much anybody else to put in bids to buy negatives and then to walk off with them.

The films themselves, at least some of them,

continued to circulate, probably through state-rights distributors as well as through pirates.

Indeed, I have seen newspaper ads for various Keystone Chaplins as late as 1929 and 1930.

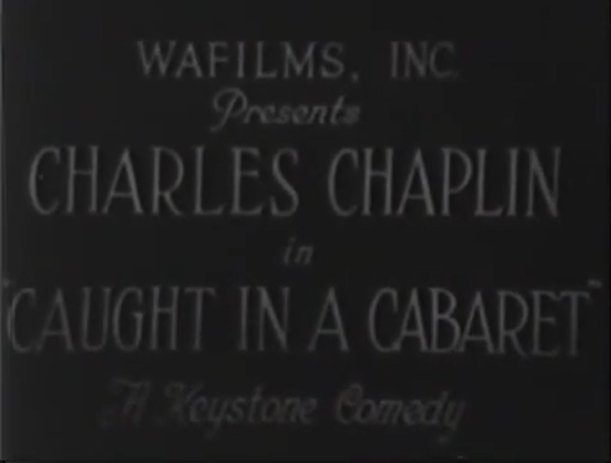

Now we get to Wafilms.

What on earth was Wafilms?

Take a look at the Wafilms edition of

Caught in a Cabaret.

Take a look also at the Wafilms edition of

His Trysting Places (or His Trysting Place —

both titles, singular and plural, were announced in the November/December 1914 newspaper ads and promotions;

the discovery of an original release print reveals that the plural version was the real version).

To my eyes, these look like silent prints made sometime in the 1920’s.

(Glenn Mitchell’s Chaplin Encyclopedia places these around 1923.)

So, what on earth was Wafilms?

Wafilms was connected with

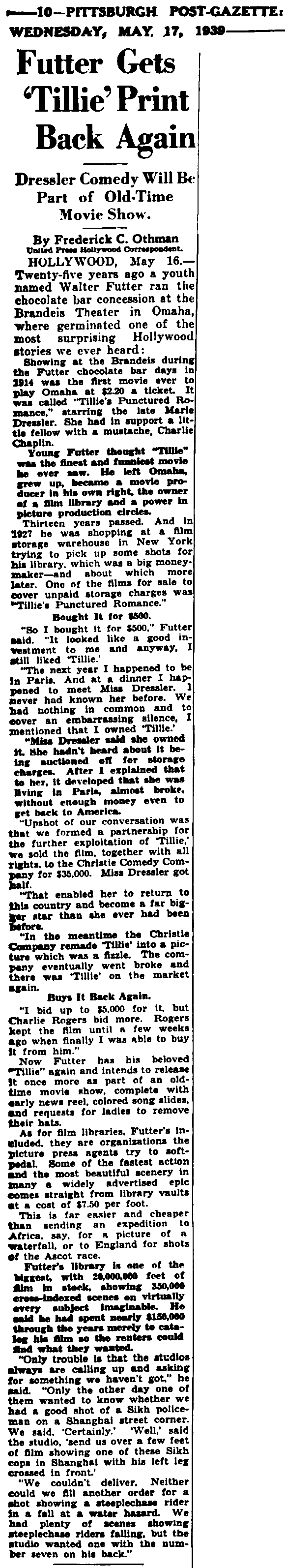

The Futter Corporation, owned by

Walter Alfred Futter

(02 Jan 1900 – 03 Mar 1958).

It quickly becomes apparent that the first three letters of Wafilms, WAF, are

Walter Alfred Futter’s initials.

Wikipedia provides further information:

“His brother, Fred, joined him in creating a stock-footage library called ‘Wafilms’.

They bought up bankrupt stock and film made by amateurs and the venture proved successful,

earning them the nickname ‘the junk-men of filmdom’.”

Wikipedia tells us that Walter established the Futter Production Company no later than 1926,

and that soon his older brother was working with him.

They continued to work together for at least a decade.

I had guessed that Wafilms purchased some Keystone camera negs at auction, or possibly purchased them from someone who had won them at auction.

Yet I am now assured by someone in the know that these were not camera negs at all, but dupes!

The credits on these two Wafilms prints prominently announce,

“Edited and Titled by SIDNEY CHAPLIN,”

which was true, if misspelled.

Sydney was on the original crew, but I don’t think he had ever received screen credit on his brother’s movies before.

It was Walter who hired him to work on these movies once again, and to create new titles filled with puns and whatnot.

Again, the music we hear on YouTube is recently added, most likely by the YouTube uploaders.

What we see on YouTube are not original Wafilms prints, but copies of copies of copies of copies....

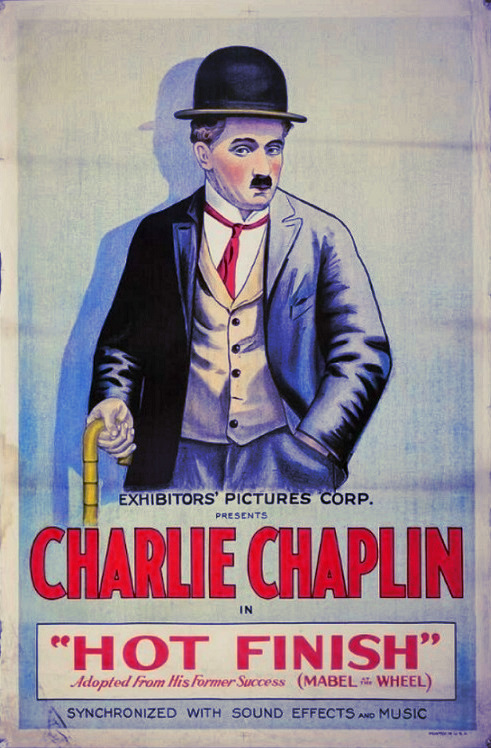

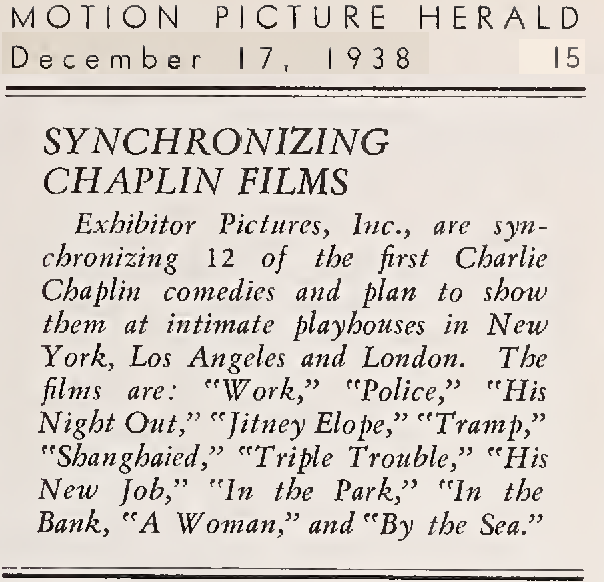

In 1930 or thereabouts, a firm called

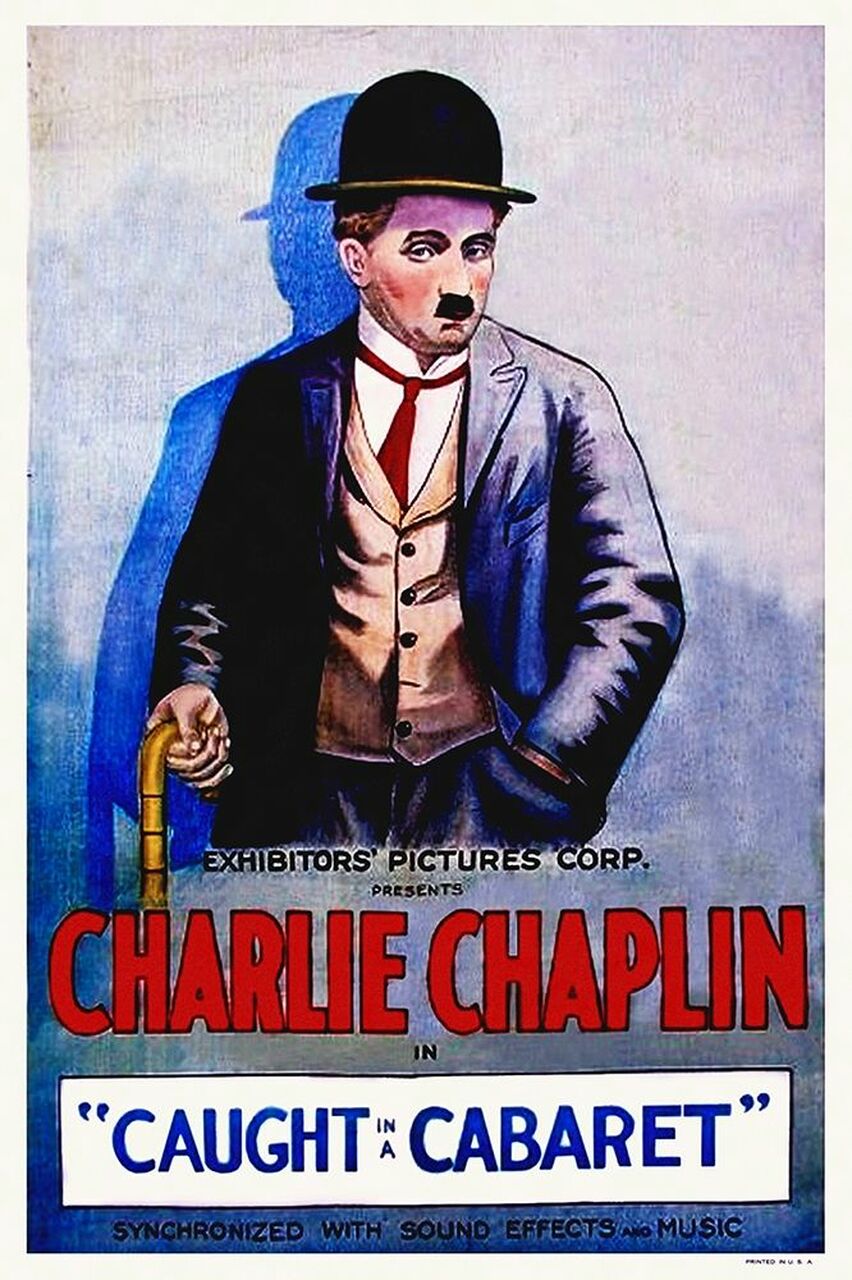

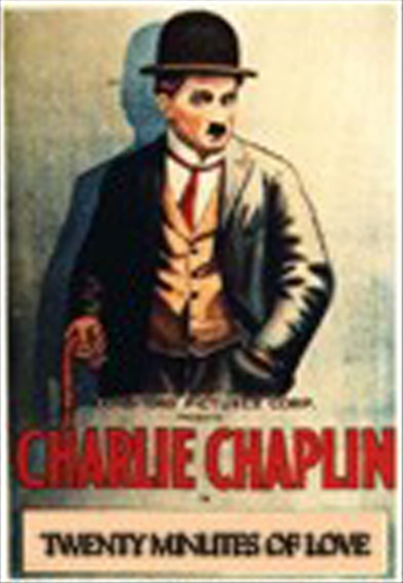

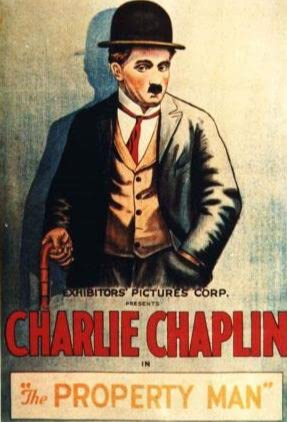

Exhibitors’ Pictures Corporation also acquired some Chaplin Keystones.

Whether EPC acquired camera negs or dupes, or whether it just copied battered release prints, I do not know.

EPC began issuing its handful of Chaplin Keystone films with music and sound effects,

with the left side lopped off to make way for the soundtrack.

I assume that these were also issued in sound-on-disc editions that would have retained the full aperture and not been cropped at all.

Heaven only knows where those prints went.

There was no attempt to stretch print to compensate for the speed difference, and so the films raced as fast as lightning.

These releases seem to have continued over the next two or three years, and it is probably impossible to trace any details.

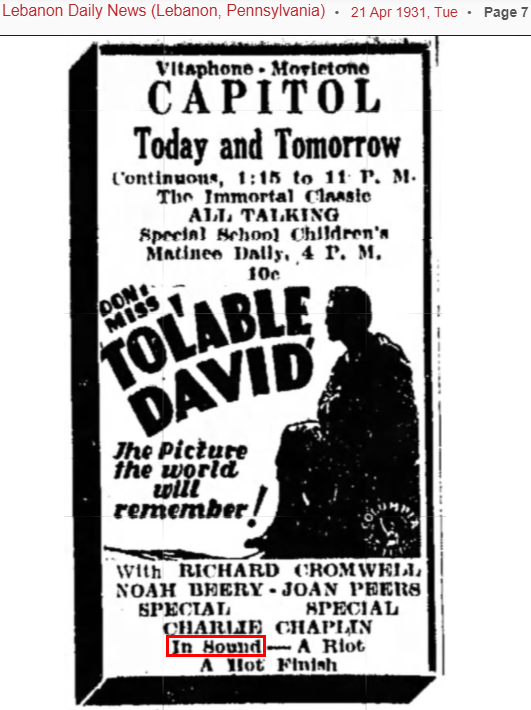

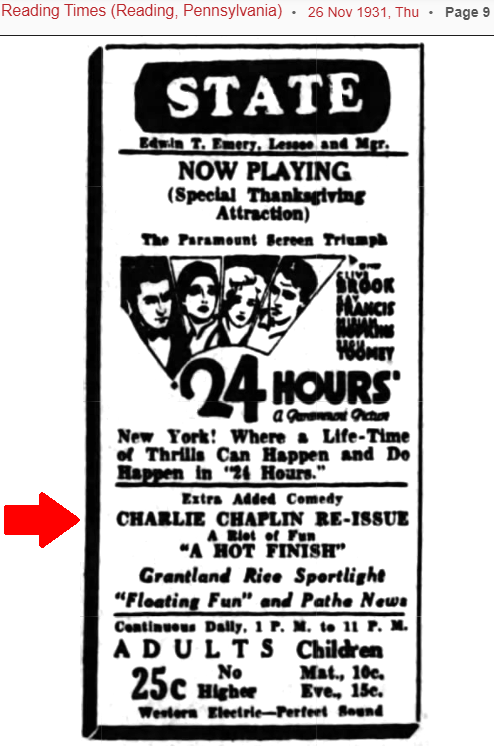

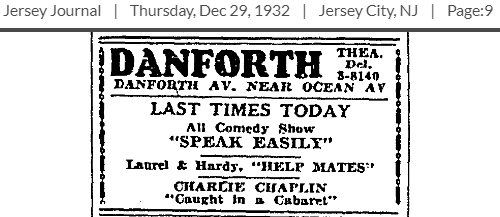

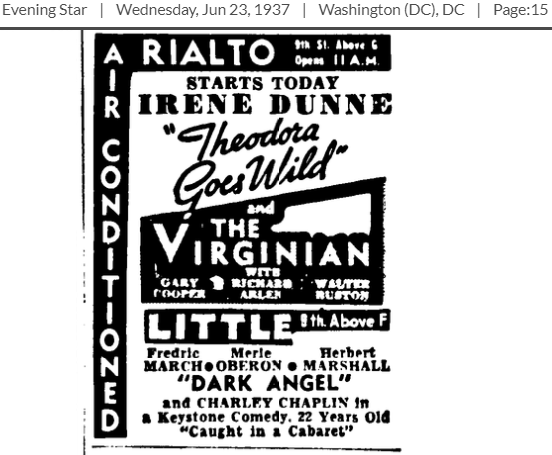

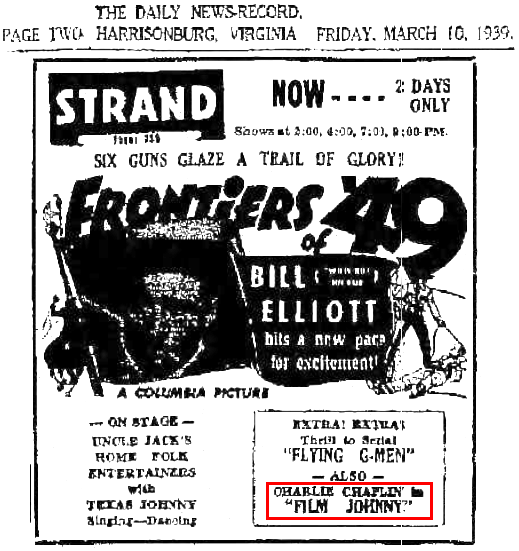

We know from evidence posted on the Internet that EPC issued music/effects editions of

Mabel at the Wheel (retitled Hot Finish),

Caught in a Cabaret,

Mabel’s Strange Predicament,

A Film Johnnie (retitled Film Johnny),

Twenty Minutes of Love, and

The Property Man.

My guess is that those six were it.

There is a possibility, of course, that EPC issued others as well.

We see from newspaper advertisements that these continued to circulate at least through 1940.

I would love so much to see and hear these.

Who did the music? What were the sound effects? I’m dying to know.

Internet searches reveal five of the posters that Exhibitors’ Pictures Corporation issued for its editions of the Keystone Chaplins.

The face was based on the poster for

A Dog’s Life

which in turn was pulled from this publicity still.

Where the other elements came from, I do not know.

What I do know is that these are terrible posters.

They are distinctly uninspired and, worse, they are undated.

We also find three more posters on IMDb:

Like I said, those and Film Johnny (formerly A Film Johnnie) were probably the only six Chaplin Keystone titles that EPC had.

The occasional press announcement provides us a few clues about where and when EPC issued these Chaplin Keystones.

It seems to me that Exhibitors’ Pictures Corporation was too small a firm to have its products shown at major cinemas.

Its films seem to have been shown in small-time venues, tenth-rate houses,

and they seem to have gotten remarkably little play.

It is difficult to be certain of this, though, because short subjects were not always advertised.

Only the feature and the name acts were listed in the display ads.

This is what I have so far found:

I would love to examine all the Exhibitors’ Pictures Corporation editions of the Chaplin shorts,

but I have no idea where to find them.

Apparently some were copied to 8mm,

and apparently those 8mm copies were run through homemade telecines and put on bottom-of-the-barrel cheapo DVD’s,

but that’s not what I want to see, nor do I want to see thousandth-generation VHS dubs uploaded to YouTube.

I want to see the EPC editions as they originally were, 35mm, in their original condition, with their original music and effects.

Where are they? Do they still exist?

Back in 1974 or thereabouts, winter of 1973/1974 probably, I saw a garbage-quality Chaplin Keystone on KOB 4 in Albuquerque.

It was Getting Acquainted.

It was utterly unwatchable, jumpy, cut up,

with extraneous footage and faked film breaks and “Just a Moment While Our Operator Makes Repairs” slides rolling in. Ugh.

It was so messy that it was impossible to follow.

It was not in the scheduled programming;

it was merely inserted after a Saturday-afternoon movie to fill in an empty ten minutes.

It was after one of the Weissmuller/Tarzan movies, which I probably watched,

though for no reason that I understood then or can possibly understand now.

Where that 16mm print came from, I do not know. I wish I had made a note about it. Oh well.

Oh. It just now comes back to me.

The following Saturday, I tuned in just as the Tarzan movie was about to end only to see what the filler would be,

and it was that same print of Getting Acquainted again.

So I watched it again, even though it was just a flickery jumble of washed-out jittering images with interruptions.

A fragment of an Exhibitors’s Pictures Corporation edition of Film Johnny appeared on a Brentwood Home Video DVD set

called “57 Classics: Charlie Chaplin” (which is worth it only for the bonus feature,

The Chaplin Puzzle, which was slipped inside in a paper envelope — if you buy a used copy, that extra disc will probably be missing).

That fragment of Film Johnny was uploaded to YouTube,

and, as you can see, it is a copy of a copy of a copy of a copy of a copy of a copy of a fragment.

Brace yourselves.

|

|

| Bootleg of Exhibitors’ Pictures Corporation reissue. Click on the image to watch. |

Original. |

The music you hear on YouTube is definitely not the music that accompanied the EPC print.

Somebody swapped the music out at some time for some reason.

Despite the horrid quality of this bootleg, we can determine some things.

Exhibitors’ Pictures Corporation of NYC lopped off the left side of the image to make room for the music track.

That was depressingly common.

Actually, prior to the 1960’s, that was almost inevitable.

I don’t think film printers at that time were capable of reducing and shifting the image to squeeze it onto a sound aperture.

|

I do not know when silents were first optically reduced to fit through a sound aperture.

In 1948, ABPC Associated British Picture Corporation reduced Metropolis to the Academy aperture, greatly to my surprise.

I know that Harold Lloyd reduced the image, not to Academy 1:1.375, but to 1:1.85 with animated curtains on the left and right sides,

for Harold Lloyd’s Funny Side of Life (1 August 1963),

and for all I know, that may have been the first time a silent was reduced to widescreen.

I wish I knew for certain.

It seems that few labs could perform such feats, and rumor had it that such manipulation of the image caused the costs to shoot up astronomically.

That’s why when Charlie reissued The Gold Rush in 1942, he sacrificed the left side.

I don’t think he had a choice.

|

Another thing we can learn from this horrid Chaplin bootleg:

There was no attempt to make any speed correction.

Sound projectors do not have speed adjustments; they are locked to a single speed, 90'/minute,

but the Chaplin Keystones were undercranked and designed to be projected no faster than about 70'/minute.

So, with the addition of the music track, the film races like mad.

Oh the questions I have about this!

What was EPC’s source? Who set the titles?

In December 1928, Chaplin began a feature called City Lights as a silent, but just after he began shooting,

it was clear that silent films were finished.

He would need to complete it as a talking picture, but he adamantly refused.

And besides, he couldn’t afford to make a talkie unless he brought in business partners and bankers and investors

and unless he subordinated himself to a studio,

none of which he would ever do again even if his life depended on it.

He wouldn’t make a talkie until 1939, when the means were more affordable,

when technicians were in plentiful supply, and when he could pay for it all himself and retain total control.

Some City Lights prints he issued in an original silent version.

I would love to see the silent version, but

David Shepard

told me that there’s only one surviving print, a bad dupe,

locked away in the Chaplin estate in Vevey. It looked so awful that he decided against using any part of it.

(No, I did not know David.

We bumped into each other a few times, spoke on the phone once, and corresponded once.

He never remembered me from one time to the next.)

Most City Lights prints Charlie issued in a slightly different music-and-effects edition.

(I know he issued a left-side-lopped-off sound-on-film version and I think he issued a full-aperture sound-on-disc version as well,

which I don’t think exists anymore, else David would probably have used it.

The OCN, original camera negative, by the way, vanished many decades ago.

How that happened, I haven’t a clue.)

To the amazement of one and all, despite being mute, the film proved to be a hit when it was finally released in January 1931,

three years into the talkie era, two years after the demise of the silent cinema.

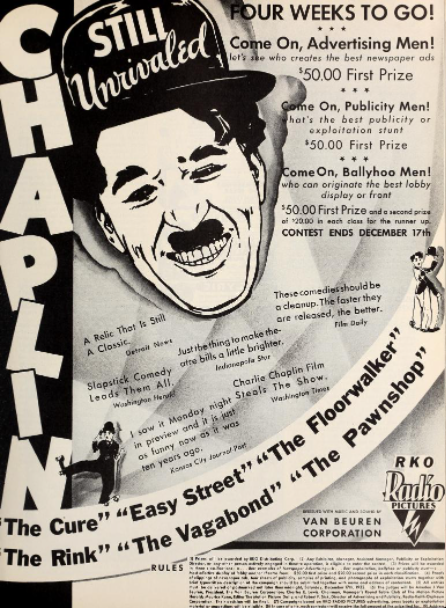

The enormous success of City Lights inspired RKO-Radio Pictures and the Van Beuren (pronounced Van Burren) Corporation

to jump on the bandwagon.

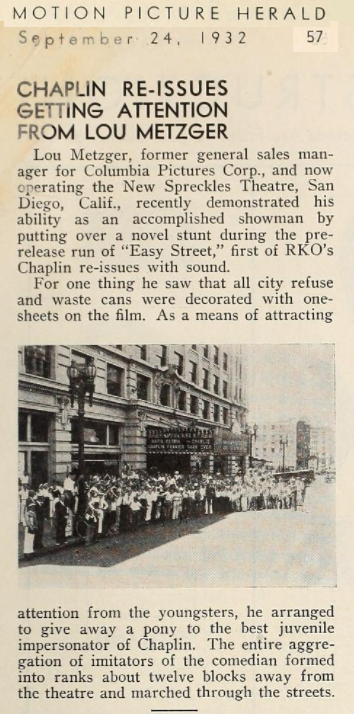

Motion Picture Herald vol. 109 no. 13, 24 September 1932, p. 57

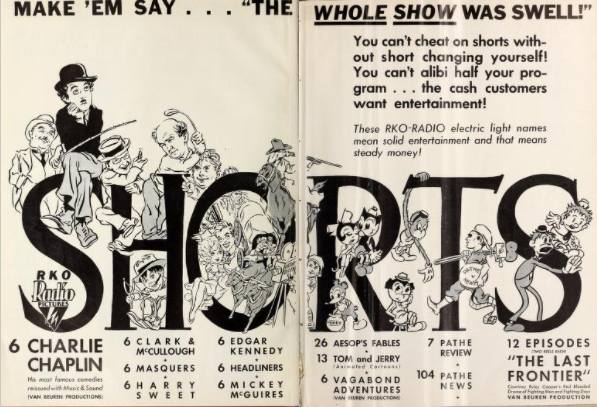

Motion Picture Herald vol. 109 no. 1, 1 October 1932, pp. 20–21

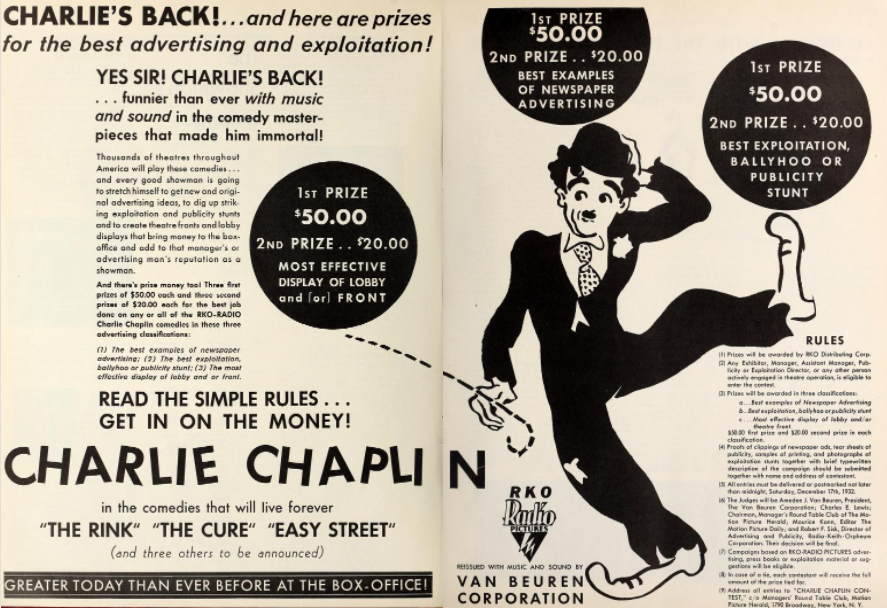

Motion Picture Herald vol. 109 no. 3, 15 October 1932, p. 39

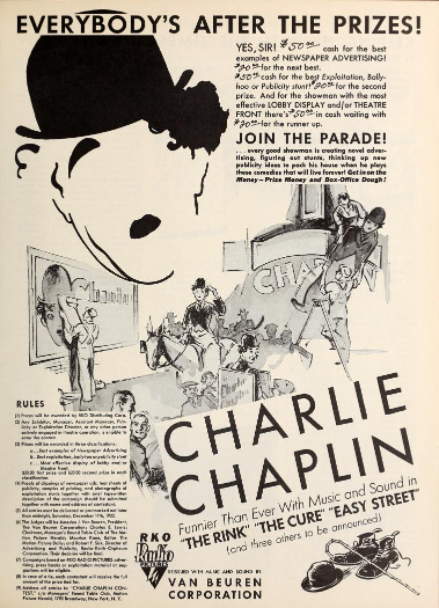

Motion Picture Herald vol. 109 no. 4, 22 October 1932, pp. 46–47

Motion Picture Herald vol. 109 no. 6, 5 November 1932, p. 53

Motion Picture Herald vol. 109 no. 8, 19 November 1932 (part 1), p. 49

Motion Picture Herald vol. 109 no. 10, 3 December 1932, p. 47

Van Beuren and RKO issued the dozen short films that Chaplin had made for the Mutual Film Corporation in 1916 and 1917,

which are delightful movies.

Of course, the left side was lopped off to make way for the soundtrack.

The top and bottom were cropped off in the projection.

(The video editions are composites that retain the Van Beuren music and sound effects but that substitute the image with other sources,

and so the framing is different, sometimes cropped equally on all four sides rather than just on three sides.)

They were terribly overspeeded, too.

They had really nice soundtracks, though, marvelous, delicious soundtracks.

Below are not scans of the original 1930’s prints, but are instead copies of copies of copies of copies of copies,

probably merged with other source materials:

19 Aug 1932,

The Cure (original silent version released on 16 Apr 1917)

30 Sep 1932, Easy Street (original silent version released on 22 Jan 1917)

11 Nov 1932, The Rink (original silent version released on 04 Dec 1916)

23 Dec 1932, The Floorwalker (original silent version released on 15 May 1916)

03 Feb 1933, The Vagabond (original silent version released on 10 Jul 1916)

17 Mar 1933, The Pawnshop (original silent version released on 02 Oct 1916)

26 Aug 1933, The Fireman (original silent version released on 12 Jun 1916)

17 Nov 1933, The Count (original silent version released on 04 Sep 1916)

19 Jan 1934, The Immigrant (original silent version released on 17 Jun 1917)

23 Mar 1934, One A.M. (original silent version released on 07 Aug 1916)

25 May 1934, Behind the Screen (original silent version released on 13 Nov 1916)

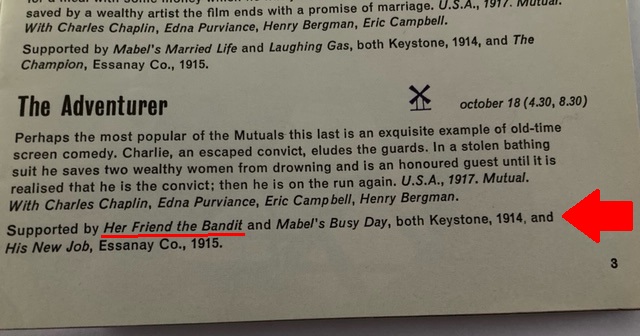

05 Jul 1934, The Adventurer (original silent version released on 22 Oct 1917)

30 Sep 1932, Easy Street (original silent version released on 22 Jan 1917)

11 Nov 1932, The Rink (original silent version released on 04 Dec 1916)

23 Dec 1932, The Floorwalker (original silent version released on 15 May 1916)

03 Feb 1933, The Vagabond (original silent version released on 10 Jul 1916)

17 Mar 1933, The Pawnshop (original silent version released on 02 Oct 1916)

26 Aug 1933, The Fireman (original silent version released on 12 Jun 1916)

17 Nov 1933, The Count (original silent version released on 04 Sep 1916)

19 Jan 1934, The Immigrant (original silent version released on 17 Jun 1917)

23 Mar 1934, One A.M. (original silent version released on 07 Aug 1916)

25 May 1934, Behind the Screen (original silent version released on 13 Nov 1916)

05 Jul 1934, The Adventurer (original silent version released on 22 Oct 1917)

These went over quite well, and the kids, too young to have seen Charlie before, loved them.

Then, to the best of my knowledge, the Van Beuren Mutuals were

withdrawn from release in 1937 when the studio closed.

I understand that they popped up again later, from Guaranteed Pictures Co., Inc.,

which combined them into three groups of four and issued them as feature films,

which I have not seen:

The Charlie Chaplin Carnival (1938),

The Charlie Chaplin Festival (01 Apr 1941), and

The Charlie Chaplin Cavalcade

[of Hits]

(Apr? 1941),

but I don’t think these got much play at all.

To my utter fascination, a reviewer mentioned that,

“The films, taken from the original negatives, are suprisingly clear and unmarred”!!!!!

(The Windsor Star,

Saturday, 11 April 1942, p. 5).

Oh where oh where did those original negatives go?

Somehow, the individual Van Beuren Mutual Chaplin shorts were later issued on the home market in 16mm and 8mm,

but I have never seen these and have no idea who the distributor was or how the distributor acquired the rights from whom.

As for myself, I had heard tell of the Van Beuren reissues, but I never saw them until just recently, at the end of 2021.

Oh that music! Oh those sound effects! To die for!

|

Pointless aside:

When Fellini said that he grew up watching Buster Keaton, Charlie Chaplin, and Laurel & Hardy at the Cinema Fulgor,

we can now pinpoint things a bit better.

He saw Buster’s Metro and First National and UA silents before his ninth birthday in January 1929,

by which time those Buster silents had been withdrawn from release and would not be seen again until the 1960’s.

The only Chaplin movies he saw were the dozen Van Beuren Mutuals, only between 1932 and 1937.

There is a chance that he also saw The Circus, City Lights, and Modern Times on their first releases,

but, if so, I don’t think he ever mentioned them.

He spoke fondly only of the eleven Chaplin movies with Eric Campbell, whom he enjoyed immensely.

As for L&H, of course, he saw each new release as it arrived in Rimini.

When he said that “the Marx Brothers blew my mind,” he referred only to “A Night at the Opera”

when it was released in Italy in late 1938.

The earlier Marx movies had not been permitted in Italy.

It would be fun someday to compile a complete dated list of films shown at the

Cinema Fulgor throughout Fellini’s childhood.)

|

So, now that the Van Beurens were off the market,

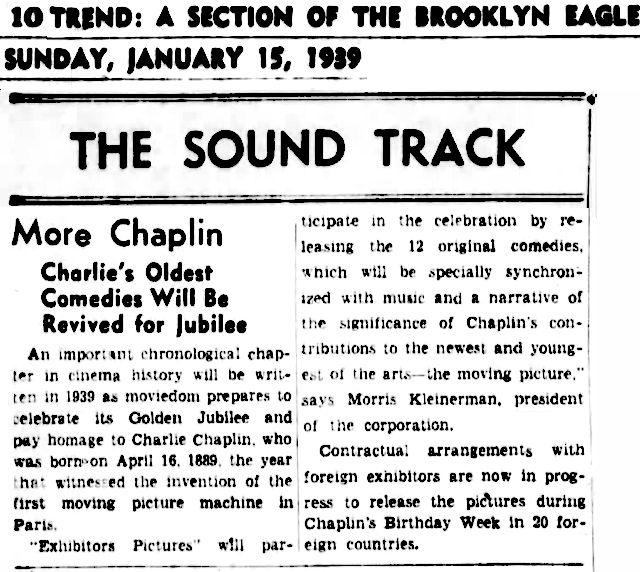

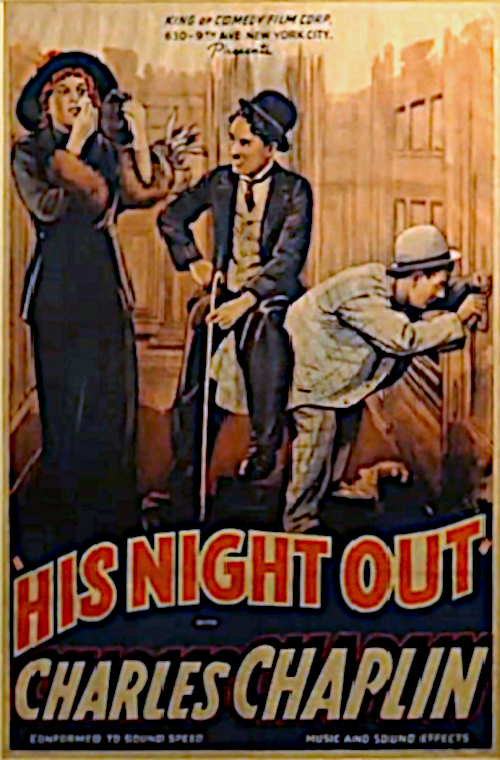

Exhibitors’ Pictures Corporation (630 9th Ave, NYC) took up some of the slack and, in 1938, acquired materials and rights

to some of the shorts Charlie had made for Essanay Pictures.

EPC offered to sell the pictures and the rights to Charlie, but he declined the offer.

Why? Because

Charlie was worried that ownership of the old negatives would invite legal challenges.

Since Charlie didn’t want them, EPC issued them on its own.

Exhibitors’ Pictures Corporation stretch-printed these flicks to return them

to something approximating what they had looked like at 70'/min.

EPC also added music and sound effects, and I am willing to bet $1,000 that the left side was lopped off to make way for the optical soundtracks.

These new editions were not released under the name of Exhibitors’ Pictures Corporation, but under a different name,

King of Comedy Film Corp. (also at 630 9th Ave, NYC), which I assume was a DBA.

I would love to see these editions, but I have no idea where to find them.

I have now seen images of two posters for the King of Comedy Film Corporation’s reissues of the Chaplin Essanay films.

One appears in a nice documentary called

Conserving Charlie Chaplin:

Let’s zoom in a bit:

Then on eBay I found item # 333592666974

and I was so tempted until I saw the price.

Once I saw the price, all my temptation got up and walked away, never to return.

I would happily pay for a nice full-sized reproduction, though, if anyone were ever to think about creating and offering reproductions.

If your temptation can withstand the price, go for it.

The seller’s tag is extremecollectiblesllc.

Good luck!

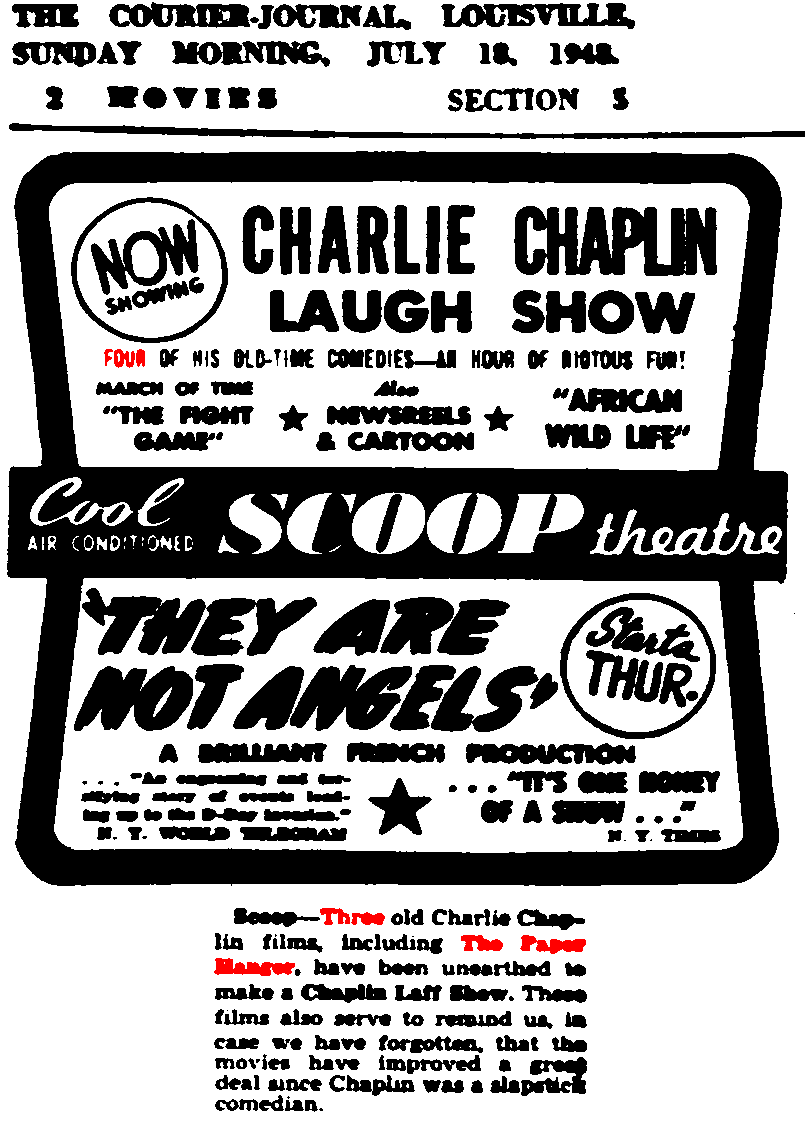

I see that in June 1941 the Casino in Pittsburgh was playing

Chaplin on Parade,

consisting of music/effects editions of His Night Out, Shanghaied, In the Bank, and The Paper Hanger,

which must have been the EPC/KoCFC editions strung together.

(Exhibitors’ Pictures Corporation,

NYC. President:

Morris

Kleinerman,

241–245 W 55th St,

NYC,

circa 1889 – circa 1962 — but he’s not the furniture guy from Tucson, who had the same name and dates.)

The story gets even more confusing.

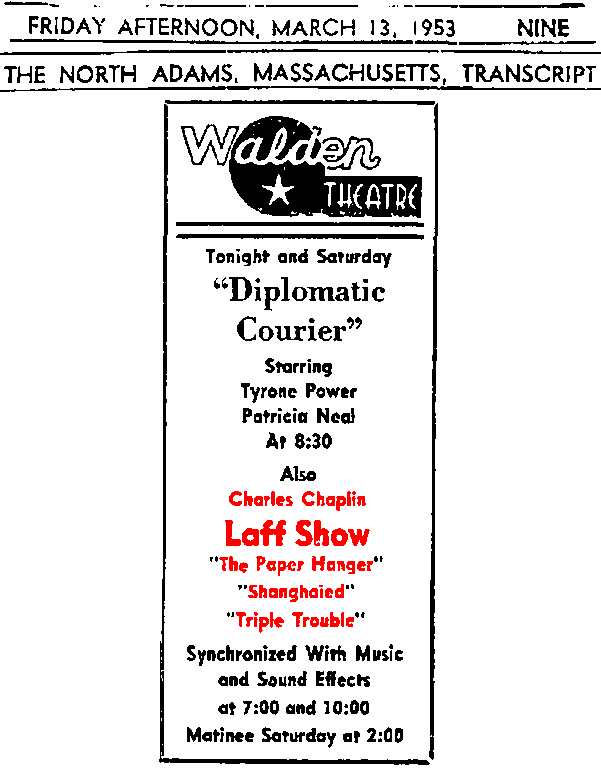

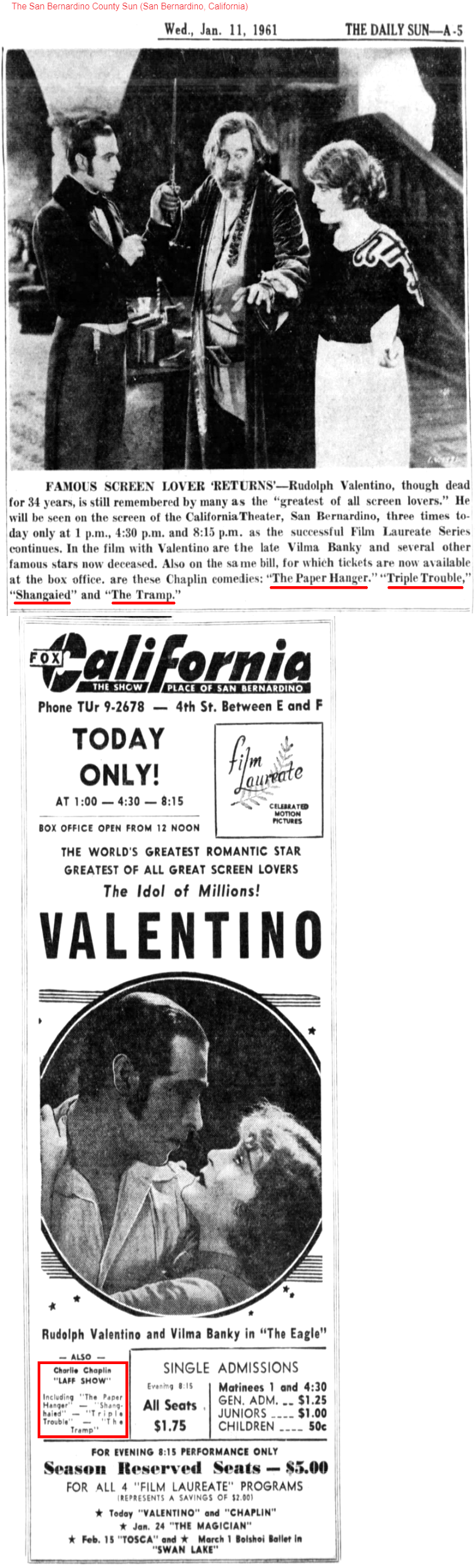

By 1948, there was a new anthology called Charlie Chaplin Laff Show, which consisted of three Essanay shorts:

The Paper Hanger (original title Work) and Shanghaied

together with an old monstrosity stitched together partly from abandoned sequences,

and partly from footage that had nothing whatever to do with Charlie.

That last abomination was an incoherent flick called Triple Trouble.

These were almost certainly the King of Comedy Film Corporation editions, stretched with music and sound effects.

Then, without warning, the Charlie Chaplin Laff Show was expanded with a fourth film, The Tramp:

Now that we have all that esoteric information hovering in the background,

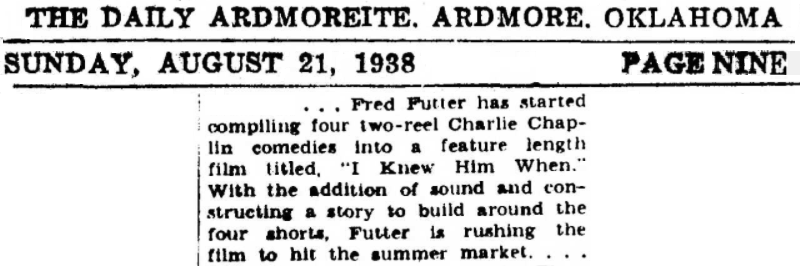

we can understand why Walter and Fred Futter got the idea

to re-use the Chaplin materials that they had added to their stock-footage library some ten or eleven years earlier.

By the way, how did Futter acquire those four camera negatives and the rights? Hold that thought.

Considering that the Keystone negatives had all been printed to death,

how were these four negatives still usable?

Were they original camera negatives or were they dupe negatives?

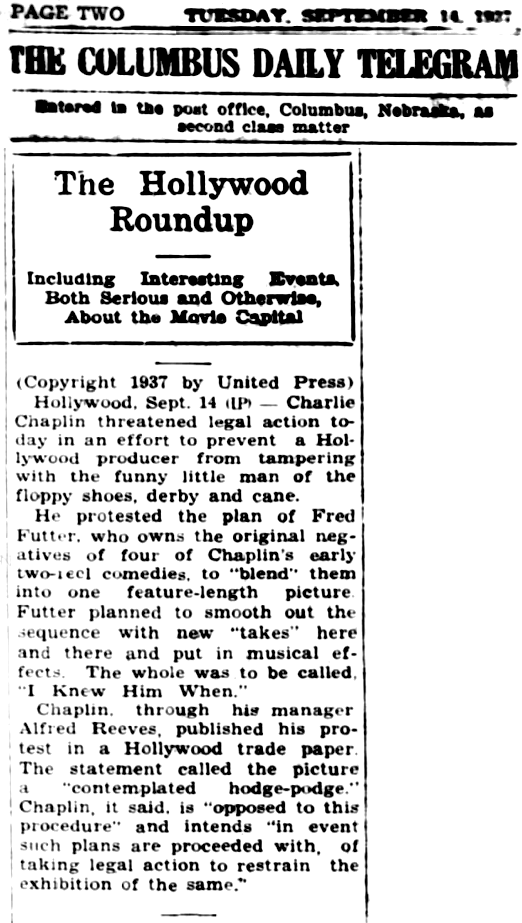

This above is a syndicated story by Douglas Churchill, LA correspondent for the New York Times wire service.

The unfunny program to which he referred was held on

the evening of Tuesday, 26 October 1937, at the

Filmarte Theater,

under the auspices of the

Southern California Film Society. The films presented were

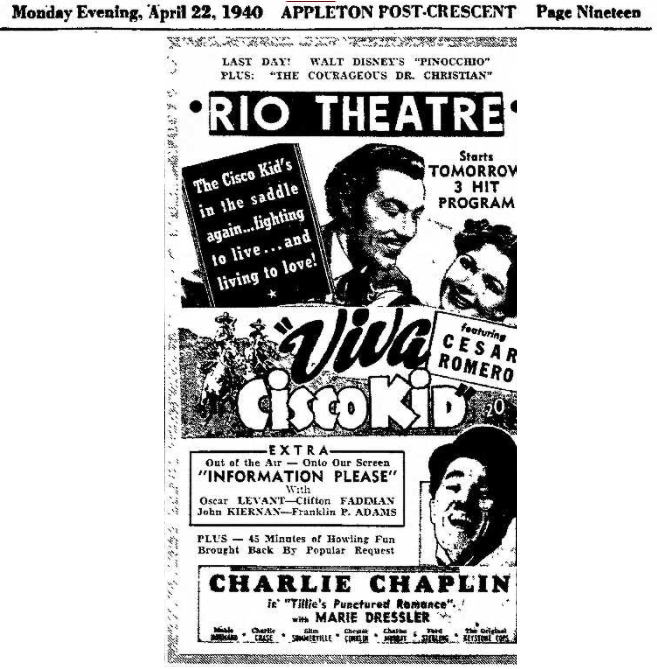

Tillie’s Punctured Romance (1914),

The Immigrant (1917),

The Pawnshop (1916),

The Floorwalker (1916),

and excerpts from

Modern Times (1936).

As for not being funny anymore, well, whatever.

I discovered half a century ago that one audience can sit in stone-cold silence through a comedy,

while the next audience two hours later will laugh riotously,

and while the next audience two hours after that will sit in stone-cold silence again.

This is a phenomenon about how people react in groups, a phenomenon that I don’t completely understand.

Also, how were the prints, how was the accompaniment, and how was the projection?

If even one of those ingredients was out of whack, then the show was murdered.

Further, since this was offered by a film society,

I can only presume that every last member of the audience had seen these films multiple times already,

and so they were all laughed out.

Rather than guffaw at material that they already knew intimately, the audience members would have just sat back and quietly enjoyed themselves.

I wish I knew what exactly happened that night.

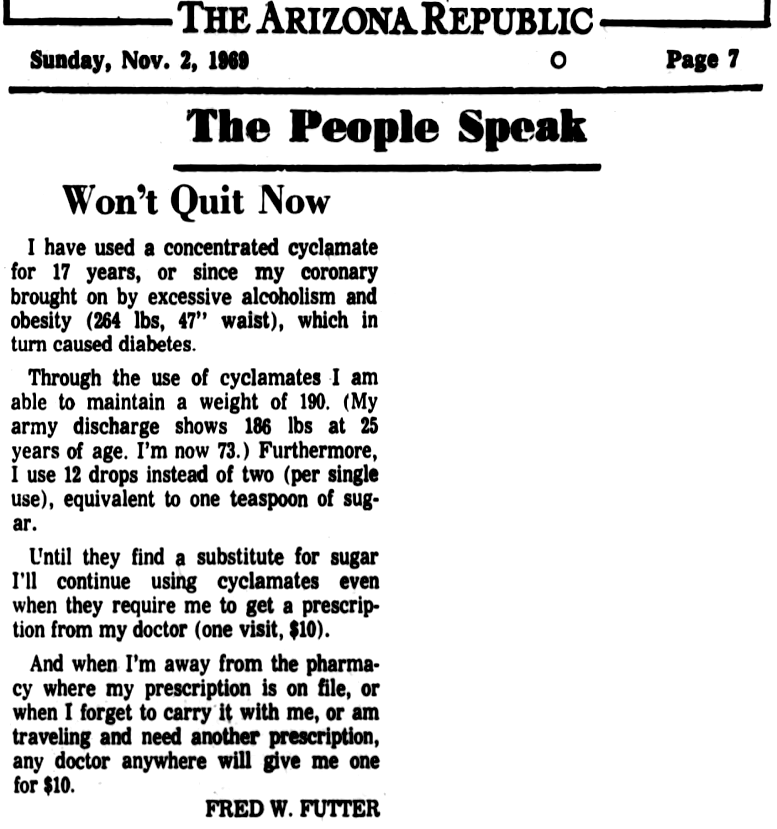

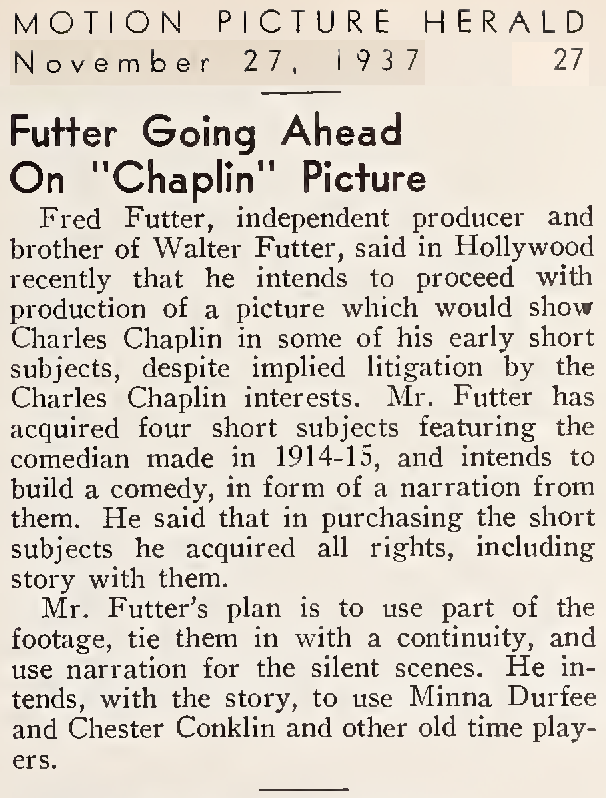

Let us learn more about this Fred Futter, shall we? Alas, there is precious little to learn.

Shall we take a look at the most relevant published information?

|

Fredrick

(or Frederick)

William Futter

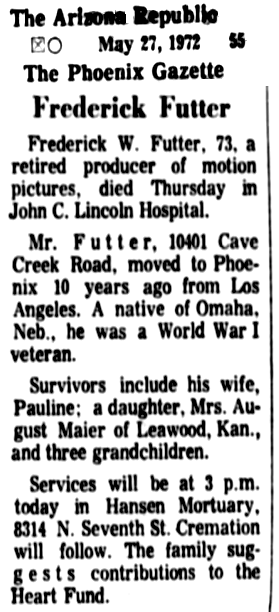

b. 28 Jun 1898 in Omaha NE next of kin: Margaret White m. Pauline Gray McVey (21 Dec 1900 – 18 Dec 1987) occupations: 1920: real-estate salesman (Fresno CA) 1936–1938: producer 1942: proprietor, Valley Bargain House (furniture shop) 1942: self-employed 1944: aeroworker residences: 110 N Thesta St, Fresno (1920, rooms with Clinton E. Haas) 6333 Lindenhurst Ave, Los Ángeles (1936–1938) North Hollywood (1941) 11506 Riverside Dr, North Hollywood (1946—1952) 5925 Satsuma Ave, North Hollywood (1958–1962) 10401 Cave Creek Rd, Phoenix AZ (1972) daughter: Mary Elizabeth Ann Futter (b. 25 Apr 1933; m. August Edwin Maier 04 Apr 1959) d. 25 May 1972 in Phoenix AZ |

I have so far found only

one other reference to Futter’s unreleased incarnation of this film, a reference that dates it vaguely to the 1930’s.

How the Futter brothers managed to acquire the dupe negatives,

well, we don’t know the specifics, but we can reconstruct the basics.

As for how they acquired the rights, well, that’s easy: There were no rights.

“Starts Thursday!”

quotes from

Okuda and Maska:

“Many Keystone comedies survive today thanks to W. H. Productions.

Unlike the products of major studios which were rented to movie theaters and then returned to the studio’s vaults,

the films of W. H. productions were sold outright to regional distributors for $80 a reel.

Thus the W. H. Keystones ‘escaped’ from the owner’s control and passed from hand to hand as time went on.”

That explains how the release prints moved around, and that explains why the world market was glutted with atrocious bootlegs.

The negatives, though, must have been sold to the highest bidders at the federal auction in 1921.

Oh how I wish I knew what happened to those negatives.

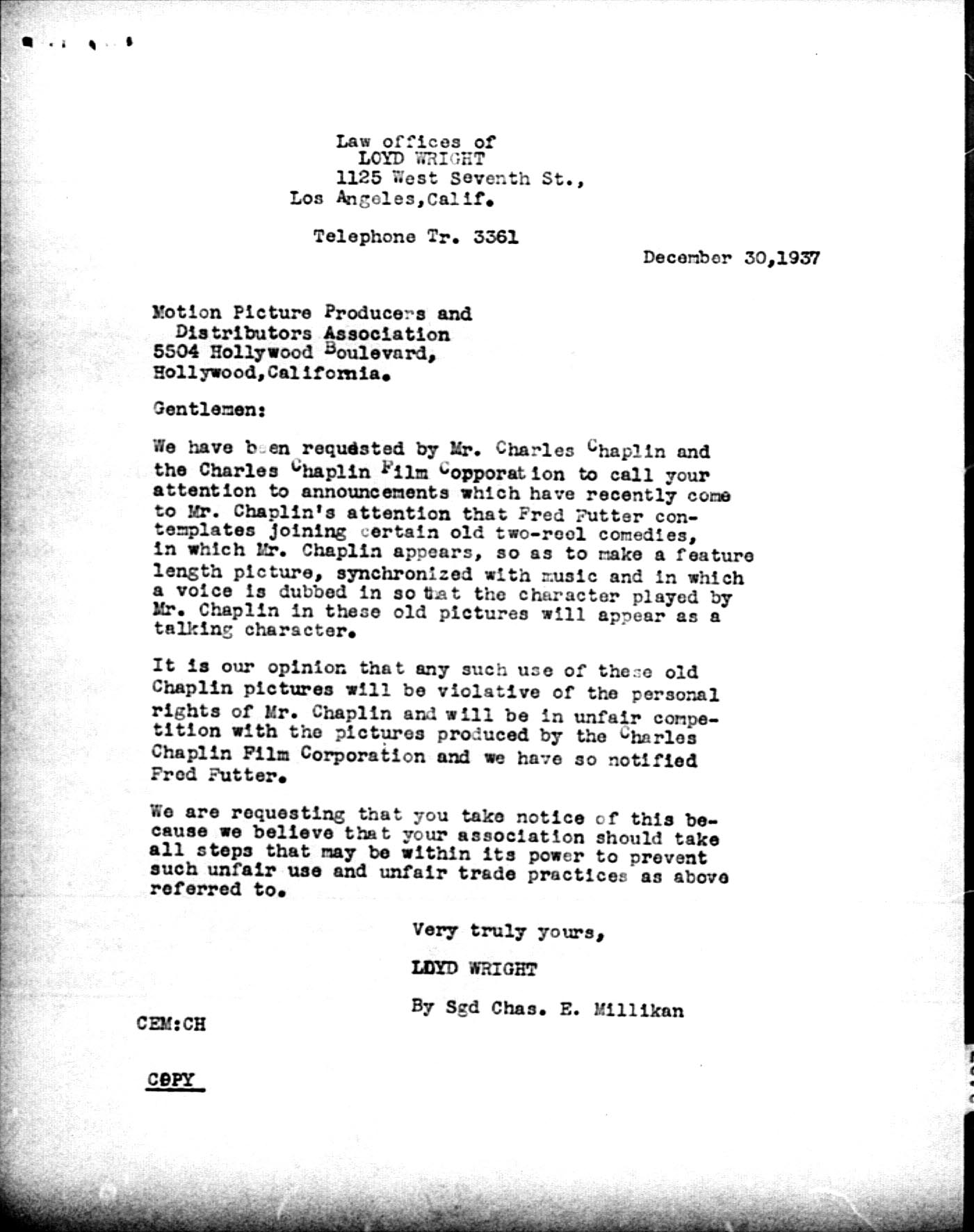

Surprisingly,

Chaplin’s company threatened legal action over Fred Futter’s proposed

re-use of the Keystone films.

Charlie’s initial objection was simply that he did not want his character to have a voice.

Futter was happy to accede to that request, and so he agreed not to dub in a voice,

but then Charlie for some reason decided to object to the project entirely.

A nice gal from the Chaplin office in Paris sent a link to Serge Bromberg,

and Serge kindly forwarded it to me.

Here it is.

It is a must-read, though sadly incomplete.

You will see that the file folder is marked “CLOSED,”

which suggests that a settlement induced Fred Futter to cancel his plans.

I Knew Him When then disappeared,

which is too bad, because, if I am reading between the lines correctly, Futter had planned to incorporate interviews with the Keystone players.

It is unclear whether he shot those interviews.

They would have been priceless and I would give almost anything to see them. Oh well.

Now that I Knew Him When was scuppered, Walter Alfred Futter moved on to produce a

40-minute abridgment

of Tillie’s Punctured Romance in 1939.

There was nothing Charlie could do to prevent this, and he never even tried.

Now, Tillie’s Punctured Romance had originally been produced in 1914 by the Keystone Studio, and Chaplin figured prominently in the cast,

though he was by no means the star of the show.

We can learn a little about this 1939 version of Tillie from

Brenton Film:

“Guy V. Thayer, Jr. was credited with ‘re-editing’

and new intertitles were by the multi-talented Mort Greene, Oscar-nominated lyricist, cartoonist, gag writer, etc.

It features a spirited orchestral score by Edward Kilenyi, Sr., with judiciously placed sound effects,

somewhat similar in style to the Van Beuren Mutuals.

With a change of the main titles, Monogram Pictures re-released this same version in 1941,

and after replacing the main titles again, Burwood Pictures released it in 1950.”

So there we have it.

I have little doubt that the same crew that worked on the 1939 edition of Tillie had also worked on I Knew Him When.

The above article gives the impression that Walter Futter acquired the camera negative and the copyright.

Nope.

If there had been any rights, they were with the owners of the stage play upon which the film was based,

and those rights had probably lapsed by this time.

As you can see from the online postings of Walter’s 1939 edition of

Tillie, it derived from a bootleg, and not just any bootleg, but about the worst bootleg that ever existed.

The quality of the image is atrocious.

We can see acceptable quality in the written introduction, but then the 100th-generation image in the film proper is unendurable.

I also know for certain that the left side was lopped off to make room for the music track.

I know that because I wound through a bit of an original nitrate print.

Where did I examine an original nitrate print?

At Don Pancho’s, of course!

I tell that exceedingly brief story in my Albuquerque essay.

|

|

| Futter’s 1939 version. | Recent transfer of the 1914 version. |

I have yet to find any detailed info about release dates for Walter Futter’s dreadful edition of Tillie.

From the quality of the print, it could definitely not have been a major release,

but a cheapo taken only by independent bookers and played as a second bill here and there.

The only posters I can find online make no mention of Futter or any studio or distributor.

Getting back to Morris Kleinerman and Exhibitors’ Pictures Corporation,

by 1948 they sold at least some of their Chaplin materials to

Jacob Harris “Jack” Hoffberg Productions.

Hoffberg definitely got some or all of Kleinerman’s Essanay’s,

but did he also get Kleinerman’s Keystone collection? I have not a clue.

Hoffberg kept at least a few of the Essanays in circulation, and

in 1961 he reprinted them and got a few bookings.

So there we go:

The Exhibitors’ Pictures Corporation’s Chaplin collection was gone.

Van Beuren and its Chaplin collection were gone.

Charlie himself was gone,

barred from returning to this country, and

for a couple of years he withdrew his film library from release.

(He began revising and

scoring and

reissuing his films in the 1950’s and 1960’s.)

Hoffberg was still around, occasionally booking a print here and there to a tenth-rate cinema.

Chaplin, from being the most famous person in the world, in an instant evaporated from public view and was largely forgotten.

A few of his public-domain Keystone, Essanay, and Mutual films still appeared on the home market in 8mm and 16mm,

but those were mostly dreadful-looking 100th-generation copies that assaulted the eyes and drove audiences away.

(Okuda and Maska devote

Chapter Two of their book to these home-movie editions.

Distributors were the Novelty Film Company of New Jersey, the Keystone Manufacturing Company of Boston, Exclusive Movie Studios,

Official Films, Atlas Films, Coast Films, Carnival Films, Walton Home Movies, Select Film Library, Regent Films, Ideal Films, and,

by leaps and bounds the finest of all, Blackhawk Films.)

Unauthorized editions of some of Charlie’s features still popped up at cinemas, and occasionally an authorized edition, too.

Every once in a blue moon, a cinema was able to arrange a special screening of an archive print of one of Charlie’s films.

Bootlegs also popped up in cinemas around the world,

and Charlie wasn’t happy.

Despite these sporadic reappearances, people in the US did not have many opportunities to see Charlie anymore.

I Knew Him When was never shown to the public.

Unless it was.

Now, take a look at this surprising newspaper display advertisement from December 1952:

Look at which four movies are included in this Quartet of Charlie Chaplin Classics —

His Prehistoric Past,

Caught in a Cabaret,

Dough and Dynamite, and

Lovelorn.

The first three were three-quarters of Futter’s I Knew Him When.

That fourth title is curious, because no Chaplin film was ever given that name.

This was either a misprint or a subterfuge.

I bet that the fourth film was actually His Trysting Places.

Bet it was.

I can find no other bookings for this Quartet.

Was this some sort of a test screening?

The US government effectively barred Charlie from setting foot in this country again.

That happened on 19 September 1952.

This Quartet booking was three months later, in December 1952.

It seems to me that Futter waited a few weeks to see if the exile was an idle threat.

Once it proved to be real, he felt free, at long last, to show his hodge-podge to the general public.

Just after this bizarre booking, I Knew Him When poked its nose out again and sniffed around a bit more.

That was in 1953.

You see, now that the US had revoked Chaplin’s visa, that left a door open to get this hodge-podge properly released.

That is when we discover this unexpected item from

Exhibitor magazine of 11 November 1953:

Indeed, when this 1938 movie was at last released (no later than

February 1954),

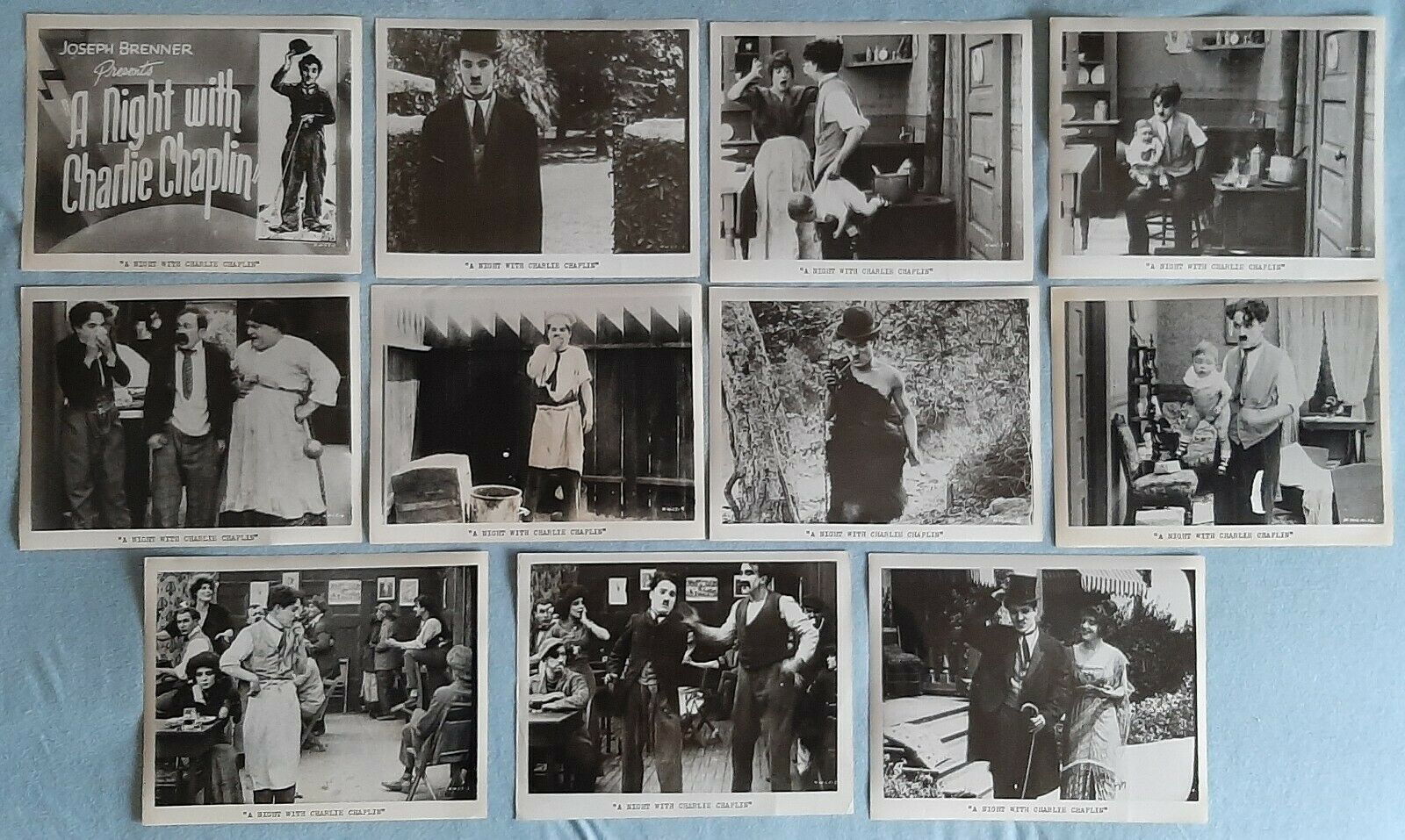

Joseph Brenner’s name was all over it.

So, who was this Joseph Brenner?

His

specialty was distributing exploitation films, the more scandalous, the better.

I’m actually a bit surprised that

Brenner would even have considered

a Chaplin program.

How Brenner knew that Futter had a movie available, I do not know.

How Futter knew that Brenner was looking for a movie, I do not know.

How they came to meet, I do not know.

My guess is that Futter, after a 15-year hiatus, finally saw an opportunity to unload his monstrosity.

Just a guess.

My guess is that Futter’s settlement with the Chaplin Film Company stipulated that he not release it,

but that it was silent on the issue of selling it to a different distributor.

Just a guess.

Suppose that he put an ad in a trade publication announcing that he had some Chaplin material available.

Maybe.

My guess is that Brenner, who was just starting his company, was enticed by the low price tag and the high value of the Chaplin name.

Just a guess.

My guess is that Brenner was prepared to do battle against the Chaplin company, if necessary, but that he was not expecting to need to,

since Charlie and his colleagues had more pressing things on their minds at the time.

Just a guess.

When we sift through the old newspapers online, we find confirmation that Brenner’s release was indeed Futter’s

hodge-podge — or, at the very least,

that it derived from the sources that Futter had used to make his hodge-podge.

A Night with Charlie Chaplin consists of the same four films that Futter had used to create I Knew Him When,

and it was advertised as a sound film. Behold:

Furthermore, let us look again at that ad that Don Pancho’s, placed:

See that?

This is not an old hodge-podge ; this is a “A NEW MASTERPIECE”

directly from the Master of Comedy, who, at the time, you must remember, was still very much alive and active and making movies.

Nonetheless, Brenner’s 1954 release might not have been identical to Futter’s 1938 version after all.

The settlement agreement with Chaplin’s company might have forbidden intercutting the four shorts,

and it might have forbidden dialogue being dubbed in.

I do not know.

The settlement is nowhere to be found, and neither is the contract between Futter and Brenner.

A Night with Charlie Chaplin was never issued as a first-run feature.

It went straight to revival houses and hence was never reviewed, as far as I know.

It was never issued on home video and it no longer seems to be available anywhere.

Perhaps it no longer exists.

The last screening I can discover is from

August 1970, when the YMCA booked it for the Parsippany Hills High School auditorium.

That was presumably 16mm.

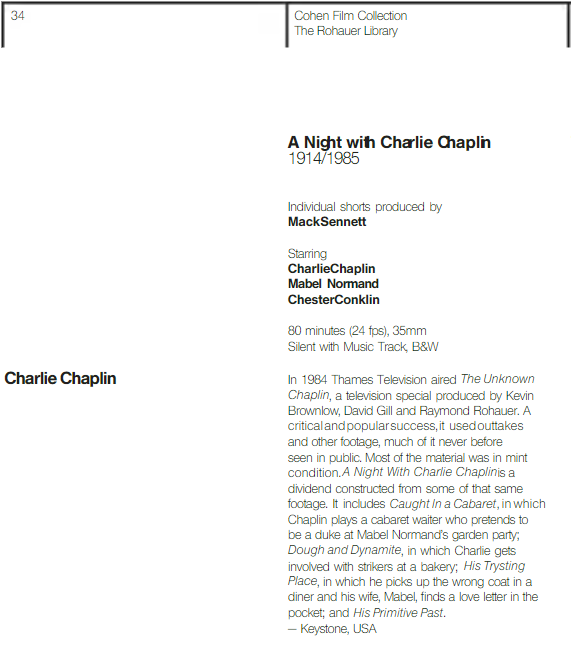

A Night with Charlie Chaplin should not be confused with a

1985 Rohauer anthology of the same name.

Or maybe it should be confused with the Rohauer anthology from 1985.

Pay attention to the Cohen Film Collection’s

catalogue summary of the 1985 film:

80 minutes rather than 61 or 70?

These catalogue entries often have wildly inaccurate running times.

The 1985 anthology was created out of the same four Keystone movies that had been incorporated into the 1938 anthology!

I don’t understand. I really don’t.

I can make wild guesses, though.

Here’s an exploratory conjecture:

We know for certain that

Ray Rohauer (who was friendly with my old friend

Charlie

Stein,

by the way — small world),

upon Chaplin’s expulsion from the US,

somehow acquired

mountains of outtakes

from the films Charlie had made for the

Mutual Film Corporation in 1916 and 1917,

outtakes that I think Charlie had ordered destroyed.

My guess — only a guess — is that Rohauer didn’t stop there.

In about 1970, he might have purchased the Chaplin materials owned by Brenner.

Just a guess, but a reasonable one.

If correct, that would certainly explain how the Rohauer edition of

A Night with Charlie Chaplin came to be.

Was this 1985 version ever shown publicly? I don’t think it was.

We do not know the quality of the image of the 1954 A Night with Charlie Chaplin,

we do not know how the transfers were made,

we do not know what the

musical accompaniment was, though I suppose it was composed by

Edward Kilenyi, Sr., and we do not know who dubbed the voices.

The four Keystone shorts that served as the raw footage for this feature

were surely derived from late reissues rather than from the originals.

Futter claimed to have the “original negatives,” though he probably did not,

but all known copies of those films had been altered since 1914!

Besides, “original” in the movie world does not always mean “authentic.”

An “original camera negative” could even have been assembled from rejects after the true “original” had worn out.

Fortunately, the four short films that constituted this feature still exist

and they are now available in better quality than they have been since the mid-1910’s:

Dough and Dynamite (26 Oct 1914)

His Trysting Places (09 Nov 1914)

Caught in a Cabaret (27 Apr 1914)

His Prehistoric Past (07 Dec 1914)

His Trysting Places (09 Nov 1914)

Caught in a Cabaret (27 Apr 1914)

His Prehistoric Past (07 Dec 1914)

|

If you want links to yet more newspaper articles that mention Fred Futter and his wife,

here they are, but they’re not terribly exciting,

just PTA stuff and fishing and so forth.

You need a subscription to Newspapers.com to access these articles.

Tue 16 Apr 1940, J. “Stew” Brown, Jr., “Sportsmen Feast on Chow Mein,” San Fernando Valley Times vol. 4 no. 31, North Hollywood p. col. 5 Thu 11 Jul 1940, “War Mothers Meet at Fete,” The Citizen-News (Valley edition) vol.36 no. 88, p. 1 col. 4 Tue 16 Jul 1940, “American War Mothers Feted at Luncheon and Program,” San Fernando Valley Times vol. 4 no. 56, North Hollywood p. col. 1 Tue 27 Aug 1940, “Distributes Watermelon to Each Visitor,” San Fernando Valley Times vol. 4 no. 68, North Hollywood p. col. 7 Tue 08 Apr 1941, “Sportsmen to Dedicate Club,” San Fernando Valley Times vol. 37 no. 7, Valley p. col. 7 Thu 10 Apr 1941, “Sportsmen Dedicate Club Rooms,” San Fernando Valley Times vol. 5 no. 29, p. E col. 6 Thu 19 Jun 1941, “Mrs. Fred Futter Heads Lankershim Fri 12 Sep 1941, “Council at Rio Vista Represented by 17 of Lank. Tue 07 Oct 1941, “Lankershim Tue 04 Nov 1941, “Mrs. Ruth Simmons Entertains War Mothers’s Chapter,” San Fernando Valley Times (North Hollywood edition) vol. 5 no. 88, p. col. 3 Fri 07 Nov 1941, “Mrs. Fred W. Futter Gives Chest Workers Praise for Help,” San Fernando Valley Times vol. 5 no. 89, North Hollywood p. 2 col. 6 Fri 16 Jan 1942, J. “Stew” Brown, “Valley Sportsmen,” San Fernando Valley Times vol. 5 no. 5, North Hollywood p. col. 8 Tue 17 Feb 1942, “Lankershim Tue 10 Mar 1942, “Sportsmen to See Movie on Oil at Dinner,” San Fernando Valley Times vol. 6 no. 20, North Hollywood p. 7 col. 4 Fri 13 Mar 1942, “Sportsmen Asked to Aid Defense,” Hollywood Citizen-News vol. 37 no. 298, Valley p. col. Fri 27 Mar 1942, “Bold Burglar Almost Takes Whole Store,” San Fernando Valley Times vol. 6 no. 24, p. 9 col. 8 Tue 28 Apr 1942, “Mrs. Milo Hissong Wins State Award Sells Tue 28 Apr 1942, “Re-elect Mrs. Futter Lankershim Fri 01 May 1942, “North Hollywood Sportsmen Conduct Annual Tournament: Garnet Glover Makes Record 450-foot Cast,” San Fernando Valley Times vol. 6 no. 34, North Hollywood p. 2 col. 6 Fri 05 Jun 1942, “‘Information’ Quiz Is Feature: Tue 16 Jun 1942, “Lankershim Tue 23 Jun 1942, “Defense Drive to Be Started by Sportsmen,” San Fernando Valley Times vol. 6 no. 49, p. 1 col. 1 Fri 26 Jun 1942, “Fred Futter Will Open Red Cross Aid Class,” San Fernando Valley Times vol. no. , p. 39 col. 2 Fri 17 Jul 1942, “Sportsmen Hear Burkhalter at ‘Cool’ Meeting,” San Fernando Valley Times vol. no. , p. 20 col. 4 Tue 08 Sep 1942, “Lankershim Tue 06 Oct 1942, “Lankershim Tue 13 Oct 1942, “Lankershim Tue 24 Nov 1942, “Lankershim Tue 15 Dec 1942, “Mrs. Dorsey McBride Give Yule Message to Lankershim,” North Hollywood Valley Times vol. 6 no. 97, p. 4 col. 8 Tue 19 Jan 1943, “Camp Fire Work also Health Talk at Fri 26 Mar 1943, “New Unit to Serve in Valley Defense: Citizens’ Service Corps Has Swart as Director; Sparrow Heads Advisers,” Hollywood Citizen-News vol. 38 no. 309, p. 2 col. 8 Tue 08 Jun 1943, “Lankershim Tue 15 Jun 1943, “Brunch to Honor Mrs. Futter at Posen Home,” North Hollywood Valley Times vol. 7 no. 44, p. 10 col. 6 Fri 18 Jun 1943, “Floral Ceremony at Lankershim Fri 09 Jul 1943, “Child Care Work to Get Under Way,” North Hollywood Valley Times vol. 7 no. 51, p. 14 col. 6 Tue 13 Jul 1943, “Lankershim School to Give Child Care,” North Hollywood Valley Times vol. 7 no. 52, p. 7 col. 5 Wed 04 Aug 1943, “Enrollment in Child Care Center Gains,” Hollywood Citizen-News vol. 39 no. 108, p. 2 col. 7 Fri 10 Sep 1943, “ Thu 16 Sep 1943, “Child Care Center Will Continue,” Hollywood Citizen-News vol. 39 no. 145, p. 2 col. 2 Tue 19 Oct 1943, “ Fri 22 Oct 1943, “ Mon 15 Jan 1945, “Sportsmen Expand to Impressive Club,” San Fernando Valley Times vol. 9 no. 4, Thu 14 Mar 1946, “Valley Camp Fire Leaders Planning Tea,” Valley Times and North Hollywood Sun-Record and Roscoe Herald vol. 10 no. 26, p. 5 col. 1 Thu 04 Apr 1946, “Hospital Supply Work Planned by Tawasis,” Valley Times and North Hollywood Sun-Record and Roscoe Herald vol. 10 no. 44, p. 7 col. 1 Wed 17 Apr 1946, “Baby Shower Featured at Meeting,” The Valley Times vol. 10 no. 55, p. 5 col. 3 Mon 06 May 1946, “Nancy Dunbar Hostesses Tawasi Camp Fire Girls,” Hollywood Citizen-News vol. 42 no. 31, p. 17 col. 3 Wed 05 Jun 1946, “Camping Plans Under Way,” Hollywood Citizen-News vol. 42 no. 57, p. 10 col. 6 Fri 20 Sep 1946, “Camp Fire Girls and Girl Scouts: Camp Fire Leaders,” The Valley Times vol. 10 no. 189, p. 19 col. 6 Wed 01 Jan 1947, “Nelson Heads Sports Club,” The Valley Times vol. 11 no. 1, p. 6 col. 8 Mon 20 Jan 1947, “Valley Club Sports Election,” The Valley Times vol. 11 no. 17, p. 6 col. 3 Sat 08 Mar 1947, “Camp Fire Girls Fete Birthday,” The Valley Times vol. 11 no. 58, p. 13 col. 6 Wed 09 Apr 1947, Lupe Saldana, “Ike Walton Jr.,” Los Ángeles Daily News p. 37 col. 2 Fri 11 Apr 1947, Norman Phillips, “Field, Stream and Ocean,” The Valley Times vol. no. , p. 14 col. 2 Fri 18 Apr 1947, “Real Estate Wanted,” The Valley Times vol. 11 no. 93, p. 22 col. 3 Fri 10 Oct 1947, “Fall Sessions Open Thursday at Monlux,” The Valley Times vol. 11 no. 243, p. 18 col. 6 Mon 13 Oct 1947, “ Tue 03 Feb 1948, “Parents Note Founders’ Day at Lankershim,” The Valley Times vol. 12 no. 29, p. 9 col. 7 Sat 18 Dec 1948, Lupe Saldana, “Ike Walton Jr.,” Los Ángeles Daily News p. 17 col. 2 Wed 09 Feb 1949, “Adron Pleads Guilt in Ferreri Slaying: Psychiatrists Divided on Sanity of Handyman as Trial Commences,” The Los Ángeles Times vol. 68, pt I Wed 09 Feb 1949, “Seek Ferreri Case Jury,” Los Ángeles Daily News p. 44 col. 5 Thu 10 Feb 1949, “Defense Counsel Paints Ferreri in Lurid Hues,” The (Los Ángeles) Mirror vol. 1 no. 106, Sat 06 May 1950, “Futter Gets Good One,” The Valley Times vol. no. , p. 9 col. 3 Wed 25 Apr 1951, “Fly Casting Tourney Swept by Anderson,” Citizen-News Valley p. 3 col. 7 Thu 20 Sep 1951, “Defense Worker, 56, Donates 33 Pints of Blood in 6 Years,” The Valley Times vol. no. , Mon 13 Feb 1956, “Association’s Schedules Reveal Red Circled Dates,” The Valley Times vol. 20 no. 37, Thu 07 Feb 1957, “PTA Activities: Lankershim,” Citizen-News vol. 52 no. 268, p. 13 col. 3 |

Now that I’ve gone this far down the rabbit hole,

I might as well explore what all I saw on TV lo those many years ago.

I remember that my parents used to watch Chaplin shorts on TV on Sunday afternoons in 1968.

They laughed wildly, but I could never see the humor.

One Sunday afternoon they called me in to watch Charlie on a rocking ship at the beginning of

The Immigrant.

I came in, looked at it for a few moments, straight-faced, and then walked away again.

(So unlike my father to call me in to enjoy anything. Entirely unlike him. He must have earned some money that week.)

Again, my memory told me lies.

The Chaplin series was Sundays at 12:30pm, true, on local TV, WOR Channel 9 in NYC,

but it was 1966, not 1968, and it ran from

09 October

through

20 November.

I did not become a convert to the Holy Temple of Silentism until a year later,

03 Dec 1967, courtesy of The Great Chase, WOR Channel 9, 7:30pm.

Had that happened earlier, I would have been much more tolerant of and curious about Charlie.

Only just now did I discover what precisely it was that my parents were viewing so religiously.

It was

The Charlie Chaplin Comedy Theatre.

In NYC, Chaplin shorts showed for five weekday mornings Monday through Friday, 25 through 29 January 1965, on WNBC Channel 4 at

6:30 in the morning.

I suspect that five-day series consisted of five of the Van Beuren Mutuals, yet it may have been a test run of

The Charlie Chaplin Comedy Theatre.

It is impossible to know for sure.

The Charlie Chaplin Comedy Theatre officially premièred on

WSUN Channel 38 in

St. Petersburg, Florida, on Wednesdays beginning

1 September 1965.

It was not a network series.

It was independent and offered to local stations.

In January 1966 it arrived at WFLD Channel 32 in Chicago and then it arrived at

WOR Channel 9 in NYC beginning on Monday, 21 February 1966, at 6:30 in the evening.

It ran every weekday through Friday, 08 April, but there was a definite problem:

The series was incomplete, and so each episode was shown thrice to overcompensate for the deficit:

THE CHARLIE CHAPLIN COMEDY THEATRE ON WOR CHANNEL 9 IN EARLY 1966

Mon 21 Feb 1966, ep. 15, One A.M.

Tue 22 Feb 1966, ep. 5, The Tramp

Wed 23 Feb 1966, ep. 9, A Night at the Show

Thu 24 Feb 1966, ep. 10, Mabel at the Wheel

Fri 25 Feb 1966, ep. 8, Police

Mon 28 Feb 1966, ep. 17, The Pawnshop

Tue 01 Mar 1966, ep. 3, The Rink

Wed 02 Mar 1966, ep. 21, The Cure

Thu 03 Mar 1966, ep. 13, The Bank

Fri 04 Mar 1966, ep. 15, One A.M.

Mon 07 Mar 1966, ep. 5, The Tramp

Tue 08 Mar 1966, ep. 1, Dough and Dynamite

Wed 09 Mar 1966, ep. 9, A Night at the Show

Thu 10 Mar 1966, ep. 10, Mabel at the Wheel

Fri 11 Mar 1966, ep. 8, Police

Mon 14 Mar 1966, ep. 6, Work

Tue 15 Mar 1966, ep. 17, The Pawnshop

Wed 16 Mar 1966, ep. 3, The Rink

Thu 17 Mar 1966, ep. 21, The Cure

Fri 18 Mar 1966, ep. 13, The Bank

Mon 21 Mar 1966, ep. 15, One A.M.

Tue 22 Mar 1966, TITLE NOT SUPPLIED

Wed 23 Mar 1966, ep. 5, The Tramp

Thu 24 Mar 1966, ep. 6, Work

Fri 25 Mar 1966, ep. 17, The Pawnshop

Mon 28 Mar 1966, ep. 9, A Night at the Show

Tue 29 Mar 1966, ep. 10, Mabel at the Wheel

Wed 30 Mar 1966, ep. 8, Police

Thu 31 Mar 1966, ep. 3, The Rink

Fri 01 Apr 1966, ep. 21, The Cure

Mon 04 Apr 1966, TITLE NOT SUPPLIED

Tue 05 Apr 1966, ep. 2, The Champion

Wed 06 Apr 1966, TITLE NOT SUPPLIED

Thu 07 Apr 1966, TITLE NOT SUPPLIED

Fri 08 Apr 1966, ep. 6, Work

Mon 21 Feb 1966, ep. 15, One A.M.

Tue 22 Feb 1966, ep. 5, The Tramp

Wed 23 Feb 1966, ep. 9, A Night at the Show

Thu 24 Feb 1966, ep. 10, Mabel at the Wheel

Fri 25 Feb 1966, ep. 8, Police

Mon 28 Feb 1966, ep. 17, The Pawnshop

Tue 01 Mar 1966, ep. 3, The Rink

Wed 02 Mar 1966, ep. 21, The Cure

Thu 03 Mar 1966, ep. 13, The Bank

Fri 04 Mar 1966, ep. 15, One A.M.

Mon 07 Mar 1966, ep. 5, The Tramp

Tue 08 Mar 1966, ep. 1, Dough and Dynamite

Wed 09 Mar 1966, ep. 9, A Night at the Show

Thu 10 Mar 1966, ep. 10, Mabel at the Wheel

Fri 11 Mar 1966, ep. 8, Police

Mon 14 Mar 1966, ep. 6, Work

Tue 15 Mar 1966, ep. 17, The Pawnshop

Wed 16 Mar 1966, ep. 3, The Rink

Thu 17 Mar 1966, ep. 21, The Cure

Fri 18 Mar 1966, ep. 13, The Bank

Mon 21 Mar 1966, ep. 15, One A.M.

Tue 22 Mar 1966, TITLE NOT SUPPLIED

Wed 23 Mar 1966, ep. 5, The Tramp

Thu 24 Mar 1966, ep. 6, Work

Fri 25 Mar 1966, ep. 17, The Pawnshop

Mon 28 Mar 1966, ep. 9, A Night at the Show

Tue 29 Mar 1966, ep. 10, Mabel at the Wheel

Wed 30 Mar 1966, ep. 8, Police

Thu 31 Mar 1966, ep. 3, The Rink

Fri 01 Apr 1966, ep. 21, The Cure

Mon 04 Apr 1966, TITLE NOT SUPPLIED

Tue 05 Apr 1966, ep. 2, The Champion

Wed 06 Apr 1966, TITLE NOT SUPPLIED

Thu 07 Apr 1966, TITLE NOT SUPPLIED

Fri 08 Apr 1966, ep. 6, Work

My parents did not see the above. They caught the repeats:

THE CHARLIE CHAPLIN COMEDY THEATRE ON WOR CHANNEL 9 IN LATE 1966

09 Oct, ep. 24, The Woman, and ep. 2, The Champion,

16 Oct, ep. 23, The Immigrant, and ep. 15, One A.M.

23 Oct, ep. 17, The Pawnshop, and ep. 3, The Rink

30 Oct, ep. 1, Dough and Dynamite, and ep. 5, The Tramp

06 Nov, ep. 17, The Pawnshop, and ep. 3, The Rink

13 Nov, ep. 9, A Night at the Show, and ep. 10, Mabel at the Wheel

20 Nov, ep. 8, Police, and ep. 13, The Bank

09 Oct, ep. 24, The Woman, and ep. 2, The Champion,

16 Oct, ep. 23, The Immigrant, and ep. 15, One A.M.

23 Oct, ep. 17, The Pawnshop, and ep. 3, The Rink

30 Oct, ep. 1, Dough and Dynamite, and ep. 5, The Tramp

06 Nov, ep. 17, The Pawnshop, and ep. 3, The Rink

13 Nov, ep. 9, A Night at the Show, and ep. 10, Mabel at the Wheel

20 Nov, ep. 8, Police, and ep. 13, The Bank

Not shown were:

4. The Jitney Elopement

6. Work

7. Shanghaied

11. The Floorwalker

12. The Fireman

14. The Vagabond

16. The Count

18. His Trysting Place

19. Behind the Screen

20. Easy Street

21. The Cure

22. The Adventurer

Two further episodes were not shown, and I do not know the episode numbers, though I would suppose they were 25 and 26. Those were the first and second halves of the abridged Tillie’s Punctured Romance. The titles of some of the episodes do not match the titles of the original films.

4. The Jitney Elopement

6. Work

7. Shanghaied

11. The Floorwalker

12. The Fireman

14. The Vagabond

16. The Count

18. His Trysting Place

19. Behind the Screen

20. Easy Street

21. The Cure

22. The Adventurer

Two further episodes were not shown, and I do not know the episode numbers, though I would suppose they were 25 and 26. Those were the first and second halves of the abridged Tillie’s Punctured Romance. The titles of some of the episodes do not match the titles of the original films.

You will notice that Tillie’s Punctured Romance is not included in this catalogue.

Neither was it included among the episodes shown by WOR Channel 9 in 1966.

Yet it was included as part of the series in Oakland, California.

The series premièred there on

Sun 13 Feb 1966

on KTVU Channel 2 and ran each Sunday at 7:00pm thereafter through

26 Jun.

And yes indeed, Tillie’s Punctured Romance was shown as part of that series, divided in two, on

29 May and

05 Jun 1966.

|

On Sun 03 Jul 1966, by the way, we find a most peculiar listing in Oakland:

but that was not a Chaplin film and it was not from 1941.

It was a Mabel Normand film from 1926

and I am truly surprised that it was shown on TV at all.

Interpretation: Channel 2’s contract for the Chaplin series had expired

but the replacement series would not begin until 10 July.

In the meantime, there was a 30-minute slot to fill.

So the station grabbed whatever 16mm film was on hand

and that’s why The Nickel-Hopper was broadcast.

It was listed as part of the Chaplin series only because that had been the time slot.

The 1941 date was just a typo.

|

We should keep in mind that in 1965, when this series first made its appearance,

Charlie’s movies were pretty hard to find, especially in copies that could be viewed without inducing migraines and seizures.

His movies did occasionally show up at a cinema, but you really had to keep your eyes peeled to catch the announcements.

Charlie was largely off the radar.

If you wanted to see Charlie, your best bet was to hope this series came to your town,

and then hope that the episodes would be shown when you weren’t at the office or in the midst of a commute.

From the uproarious laughter emanating from my parents in the autumn of 1966,

I wrongly developed the impression that they liked Charlie Chaplin.

Nothing could have been further from the truth.

As I would learn when I underwent that extreme conversion and became a (pretty much secret) fan myself,

my parents couldn’t care less and had no interest in seeing any more of the guy.

Whether they had gone through their own extreme conversion, I do not know.

Perhaps they didn’t want to see Charlie anymore because they knew I would necessarily sit next to them.

That could have been the reason. I really don’t know. I really don’t know.

Or maybe it was that they simply didn’t want to be seen together anymore,

or they didn’t want to do anything together anymore.

I really don’t know.

There’s nothing like good comedy to bring people closer together, or to drive them further apart.

Then in 1981, The Charlie Chaplin Comedy Theatre came to Albuquerque, on the PBS member station KNME/5.

| Sat 07 Feb 1981 | 7:30pm | Dough and Dynamite |

| Sat 14 Feb 1981 | 7:30pm | The Champion |

| Sat 21 Feb 1981 | 7:30pm | The Rink |

| Sat 28 Feb 1981 | 7:30pm | The Jitney Elopement |

| Sat 07 Mar 1981 | 7:30pm | |

| Sun 08 Mar 1981 | 11:30am | [The Jitney Elopement] |

| Sat 14 Mar 1981 | 7:30pm | |

| Sat 21 Mar 1981 | 7:30pm | |

| Sat 28 Mar 1981 | 7:30pm | Police |

| Sat 04 Apr 1981 | 7:30pm | A Night at the Show |

| Sun 05 Apr 1981 | 11:30am | A Night at the Show |

| Sat 11 Apr 1981 | 7:30pm | [Mabel at the Wheel] |

| Sun 12 Apr 1981 | 11:30am | [Mabel at the Wheel] |

| Sat 18 Apr 1981 | 7:30pm | The Floorwalker |

| Sun 19 Apr 1981 | 11:30am | The Floorwalker |

| Sat 25 Apr 1981 | 7:30pm | Tillie’s Punctured Romance, Part 1 |

| Sun 26 Apr 1981 | 11:30am | Tillie’s Punctured Romance, Part 1 |

| Sat 02 May 1981 | 7:30pm | Tillie’s Punctured Romance, Part 2 |

| Sun 03 May 1981 | 11:30am | Tillie’s Punctured Romance, Part 2 |

| Sat 09 May 1981 | 7:30pm | The Fireman |

| Sun 10 May 1981 | 11:30am | The Fireman |

| Sat 16 May 1981 | 7:30pm | The Bank |

| Sun 17 May 1981 | 11:30am | The Bank |

| Sat 23 May 1981 | 7:30pm | The Vagabond |

| Sun 24 May 1981 | 11:30am | The Vagabond |

| Sat 30 May 1981 | 7:30pm | One A.M. |

| Sun 31 May 1981 | 11:30am | One A.M. |

| Sat 06 Jun 1981 | 7:30pm | The Count |

| Sun 07 Jun 1981 | 11:30am | The Count |

| Sat 13 Jun 1981 | 7:30pm | The Pawnshop |

| Sun 14 Jun 1981 | 11:30am | The Pawnshop |

| Sat 20 Jun 1981 | 7:30pm | His Trysting Place |

| Sun 21 Jun 1981 | 11:30am | His Trysting Place |

| Sat 27 Jun 1981 | 7:30pm | Behind the Screen |

| Sun 28 Jun 1981 | 11:30am | Behind the Screen |

| Sat 04 Jul 1981 | 7:30pm | Easy Street |

| Sun 05 Jul 1981 | 11:30am | Easy Street |

| Sat 11 Jul 1981 | 7:30pm | The Cure |

| Sun 12 Jul 1981 | 11:30am | The Cure |

| Sat 18 Jul 1981 | 7:30pm | The Adventurer |

| Sun 19 Jul 1981 | 11:30am | The Adventurer |

| Sat 25 Jul 1981 | 7:30pm | The Immigrant |

| Sun 26 Jul 1981 | 11:30am | The Immigrant |

| Sat 01 Aug 1981 | 7:30pm | The Woman |

| Sun 02 Aug 1981 | 11:30am | The Woman |

I valiantly attempted to watch this series.

I gave up after the first half of Tillie.

(I would have sworn in every court of law that the series had been broadcast from about August through October 1980,

and I would have been charged with perjury. Memory is the illusion that we can recall the past.)

The shows were gawdawful. What sources were used to make those prints?

Did they derive from the masters/submasters held by Morris Kleinerman and Exhibitors’ Pictures Corporation and Jack Hoffberg of NYC?

Did Hoffberg return some of the materials to Kleinerman in 1956?

Or had Hoffberg simply gained nonexclusive rights to the Chaplin materials back in circa 1948?

It all gets so confusing.

The newspaper article above by Allen Rich, telling of Kleinerman’s attempt to get the early Chaplin shorts turned into a TV series

indicates that yes, he/it/they may indeed have been the source for at least a handful of the prints.

I understand that Bill Everson was involved in a consulting capacity on this series. Details? Nope. No details.

I suppose that Bill loaned a few of his own prints to Vernon for this series.

Where did Bill get his prints?

Most likely from MoMA, surreptitiously.

The CCCT prints were copied from quite good materials, for the most part,

and they were speed corrected (stretch printed) and, when possible, they were properly printed to retain the full Silent aperture.

Unfortunately, some of them were shortened to fit into the time slot.

Also, many titles were deleted, replaced by narration.

Above is an episode of The Charlie Chaplin Comedy Theatre,

not a thousandth as bad as I remember, but still no good.

That sickly so-called music, licensed from the royalty-free Thomas J. Valentino Production Music Library,

and that inane narration conspire to drain every last drop of comedy away,

and the result is about hilarious as an industrial examination of the medical effects of sodium hydroxide.

Further, this is one of the lesser flicks that Charlie did for Essanay.

He must have had some rough going that month, because he just didn’t get anything right.

I can’t imagine that anybody ever enjoyed this little movie, not then, not now, not at any time in between.

Terrible movie.

The year at Essanay, 1915, was the nadir of Charlie’s career.

He made some good stuff during that year, but he also made a lot of junk.

Let me explain.

At Keystone in 1914, Charlie had the support of a large band of merry funmakers who were forever pitching in ideas.

When he spent 1915 working at Essanay, he had no support at all.

He was on his own, entirely on his own.

He had to be his own writer and his own gagman, and, truth be told, he was pretty rotten at the job.

He was as bad as the Chaplin imitators.

As a matter of fact, in my opinion, he was a Chaplin imitator,

trying to mimic the character in the earlier Keystone films,

and doing a terrible job of it.

(Edna’s always worth watching, though, and she makes the Essanays bearable. Impossible not to love Edna.)

At some time or other, Charlie brought in a vaudevillian named

Vincent Bryan to help out.

Charlie learned, though, he learned pretty quickly, and by the time he got his next job at Mutual in 1916,

he knew what he was doing — and he had found some superlative collaborators, to boot.

At Mutual, Charlie had a constant stream ideas from Vincent Bryan as well as from

Maverick Terrell,

his uncredited scenarists and gagmen.

That was in addition to his stock actors, Henry Bergman, Albert Austin, and, most importantly of all, Eric Campbell.

That is why the Mutual films stand out from all the other Chaplin flicks,

and which is why the films were made so quickly, in a mere eight to ten weeks each.

Part-way through his final Mutual film, The Golf Links,

his treasured Eric Campbell got drunk, flipped his car over and got crushed to death.

His passengers and the people in the car he smashed into were injured, but not seriously.

That was the end of the best collaborator Charlie ever had.

Charlie abandoned The Golf Links and ceased listening to anybody’s ideas or advice.

The remainder of his movies were solo efforts, or nearly so.

They were not collaborations, and it shows.

About the abridged two-part Tillie’s Punctured Romance,

I bet it was copied from the Walter Futter version. Bet it was.

I watched the first of those two episodes and the picture quality was so atrocious that I couldn’t even follow the story.

That is when I realized that I just couldn’t take it anymore.

It was these and other such presentations that made my entire generation,

and the generation before us and the generation after, detest Charlie Chaplin.

When we wanted to watch silent movies in the 1960’s and 1970’s,

this is the sort of punishment we were required to endure,

only it was usually much worse:

terrible presentations of terribly murky and flickery 100th-generation prints

terribly projected with terrible music scores or no music at all

and often with terrible narration and terrible re-editing and terrible abridging.

In the 1980’s, things finally began to get a lot better,

thanks to Kevin Brownlow and David Gill and Carl Davis and John Lanchbery and their buddies

who made the world a far better place.

FURTHER REFERENCES TO THE CHARLIE CHAPLIN COMEDY THEATRE:

The Charlie Chaplin Comedy Theatre Vol. 1

The Charlie Chaplin Comedy Theatre Vol. 2

Steve Hoffman Music Forums: Charlie Chaplin question

Ted Okuda, David Maska, Charlie Chaplin at Keystone and Essanay: Dawn of the Tramp (NY: iUniverse, 2005)

John McElwee, Greenbriar Picture Shows: Comedy’s Comeback Continues, 21 April 2011

Lisa Stein Haven, Charlie Chaplin’s Little Tramp in America,1947–77 (Palgrave Macmillan, 2016)

The Charlie Chaplin Comedy Theatre Vol. 1

The Charlie Chaplin Comedy Theatre Vol. 2

Steve Hoffman Music Forums: Charlie Chaplin question

Ted Okuda, David Maska, Charlie Chaplin at Keystone and Essanay: Dawn of the Tramp (NY: iUniverse, 2005)

John McElwee, Greenbriar Picture Shows: Comedy’s Comeback Continues, 21 April 2011

Lisa Stein Haven, Charlie Chaplin’s Little Tramp in America,

Throughout the silent era, 1895 through 1929, silent films were generally treated with respect.

They were presented more or less properly, in prints that were usually quite good,

shown at handsome playhouses, accompanied by a full orchestra (in the first-run deluxe houses),

by a massive pipe organ (in the neighborhood houses), by a pit band (in smaller houses),

by a piano (in third-run houses), by such automatic instruments as the Photoplayer (in the smallest houses),

or even by multi-platter gramophones that could fade from one bit of mood music to another.

As soon as Hollywood made a business decision to quit making silents,

all the musicians were fired (in 1929 during the Great Depression),

the orchestra pits were covered over with concrete to increase seating, and

the pipe organs were sold to private collectors or junked.

The new projectors had no settings for silent films.

So when a silent film was revived, it could only be run on equipment it was never designed for

and the music had to be canned or dispensed with altogether.

The studios, convinced that their silent collections had no further monetary value, burned most of the negatives and prints,

and so later prints of silents were murky dupes that hurt the eyes and induced headaches.

The silents were then accompanied, sometimes, by new narration designed to make them look silly.

Editorials plastered the pages lauding the new cinematic advancements and disparaging the crudity of old.

This is sort of like Rembrandt’s paintings all being burned

but occasionally exhibited only in black-and-white photocopies,

accompanied by rude captions that attempt to discredit him in favor of Jackson Pollack;

or it is rather like all of Dvořák’s works being destroyed with only a single passage preserved on a kazoo,

with disparaging liner notes provided by Motorhead’s PR guy.

Silent cinema was murdered, and it was only beginning in 1980, and especially now with digital restoration,

that silent cinema has slowly been coming back to life,

but only in a handful of cinemas.

I am infinitely grateful for the recent restorations of the Chaplin Keystones

and I can hardly wait until even better and more complete restorations eventually hit the market —

if they do ever hit the market. Hope so. I would gladly pay for them a second time. Gladly.

The Keystone Chaplins are not great art. They are not art at all. They’re total rubbish.

They’re just a bunch of fairly young people goofing around, having a breezy time, throwing bricks at one another,

shoving each other into Echo Lake, and that’s it.

I find that pointless nonsense indescribably refreshing to watch,

especially because the characters are so preposterously one-dimensional and hyperbolic.

THE MISSING MOVIES. Oh, and just to get it out of my and everybody else’s system:

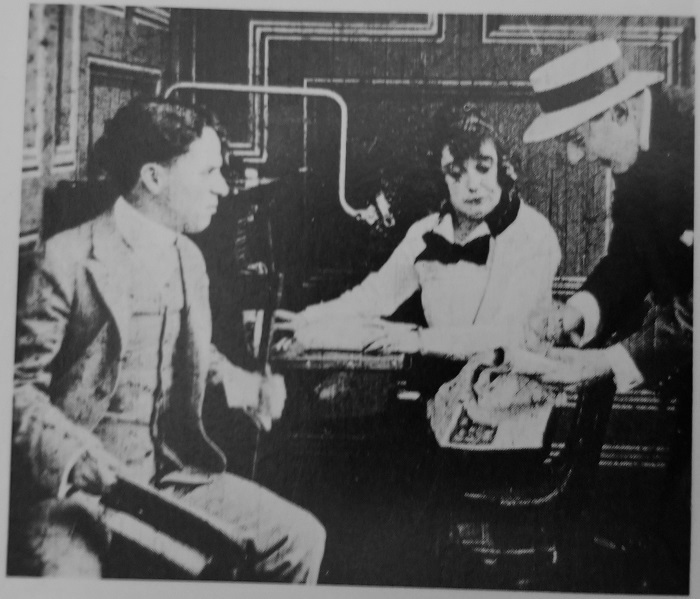

Here are the only known surviving frames of a mystery movie.

Maurice Bessy’s book (pages 25 and 46) includes two frame enlargements of a movie that nobody alive has seen

and that nobody has been able to identify with certainty.

You see, back in 1926, a cinema in France was running a bootleg print of a Chaplin movie,

and the projectionist needed to remove some frames due to damage.

The projectionist allowed 15-year-old Bessy to fish them out of the trash bin and souvenir them.

Here are all three of those two frames.

(Where the middle frame was published, I have no idea.

I had heard tell of it, but I was surprised to find it

on the Internet.)

Maurice Bessy, Charlie Chaplin (NY: Harper & Row, 1985), p. 42 (snapped with my Smartphone).

Does that really look like Charlie on the left? A definite maybe.

Snagged from TheFilmeDiary.

Does that really look like Charlie on the left? A definite maybe.

Maurice Bessy, Charlie Chaplin (NY: Harper & Row, 1985), p. 25 (snapped with my Smartphone).

Does that really look like Charlie on the left? Absolutely! No doubt about it!

The frame was torn.

Sorry, I can’t identify the actor on the right. He looks somewhat familiar but I can’t place him.

There was some speculation that these three frames might have been snipped from

the long-lost Charlie movie called

Her Friend the Bandit.

I really don’t think so.

You see, in these frames, Mabel Normand is an office switchboard operator.

In

Her Friend the Bandit, on the other hand,

Mabel was a socialite named Mrs. Mabel De Rocks.

The source of that information remains a mystery to me.

So this appears to be a mismatch.

These three frames derive from a different movie.

A possibility, put forth by

TheFilmeDiary and by Brent E. Walker in his book,

Mack Sennett’s Fun Factory (p. 288), is that these frames are from

How Motion Pictures Are Made,

which is a reasonable guess, certainly.

If that is correct, this would have been Charlie’s first moment in front of a movie camera.

Below is a description of

How Motion Pictures Are Made, and it certainly seems plausible that this is a match.

Now, let’s ponder Her Friend the Bandit.

I see that others have pondered this, too.

This has been been an itch I’ve never been able to scratch from the time I first learned about it at age thirteen.

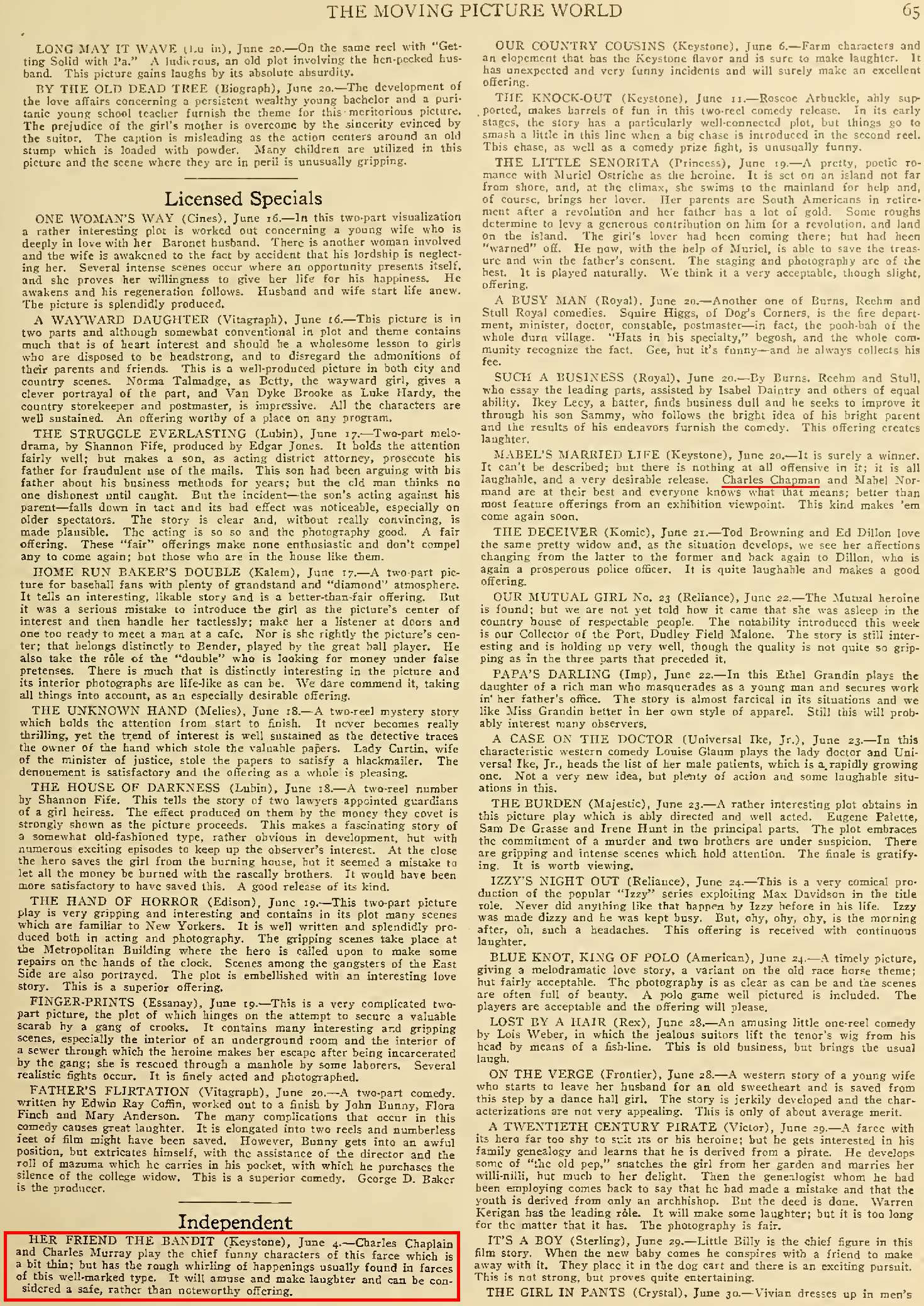

I was surprised to read in Glenn Mitchell’s Chaplin Encyclopedia (London: Batsford, 1997, now out of print)

that various scholars have questioned whether Charlie really was in this movie.

Indeed, they point out the misspelling, “Charles Chaplain,” in the above summary to explain their doubts.

Oh please! Keystone did not name cast or crew in the credits, but only in press announcements.

As the word got round about their identities,

people made their best guesses as to the spellings.

When you look through the ads and press announcements,

you will find that our Charlie was quite routinely identified as “Chas. Chaplain.”

There is nothing surprising about that.

Look above at the middle of column 2, under the entry for Mabel’s Married Life,

and you will see that he magically becomes “Charles Chapman.”

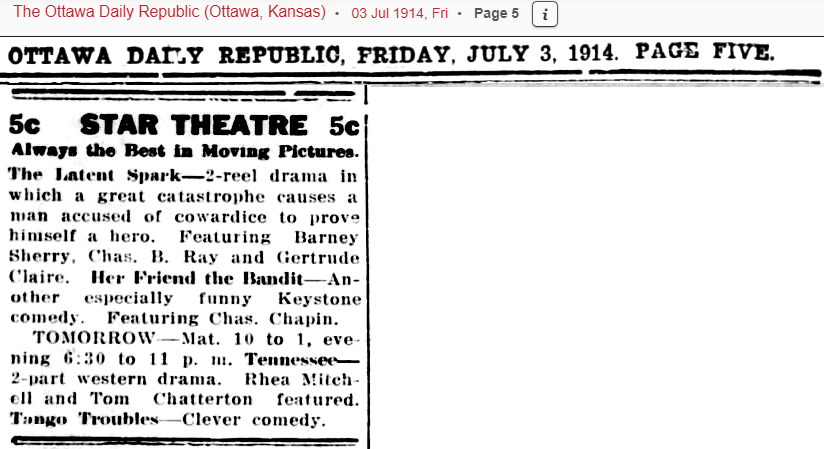

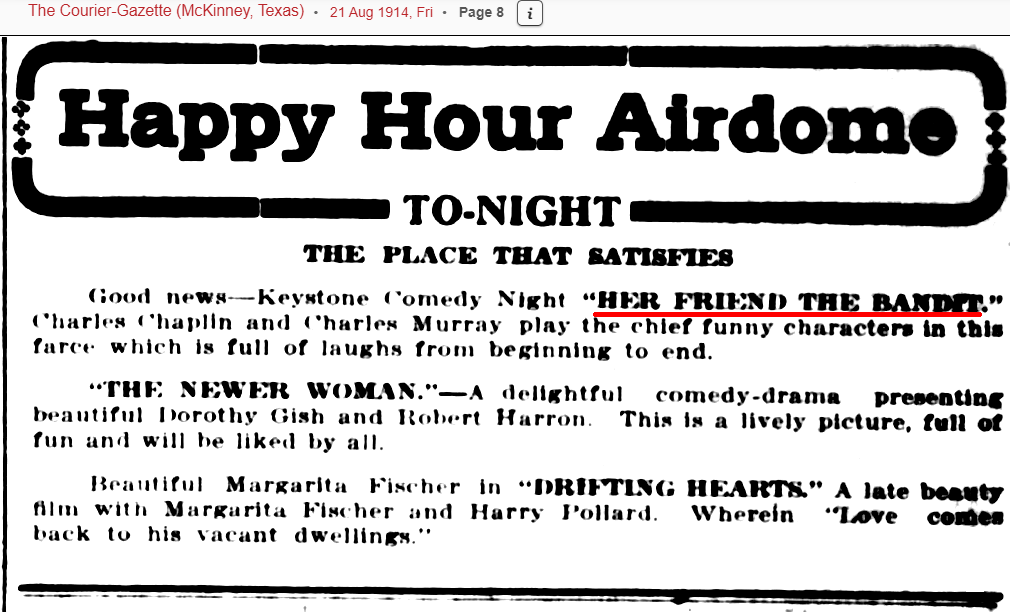

In the announcement below, he becomes “Chas. Chapin,”

and below that he becomes “Chas. Chappel”!

I hope that the above four newspaper clippings are sufficient to demonstrate that Charlie was indeed the lead player in Her Friend the Bandit.

All doubts on that matter should now be cast aside.

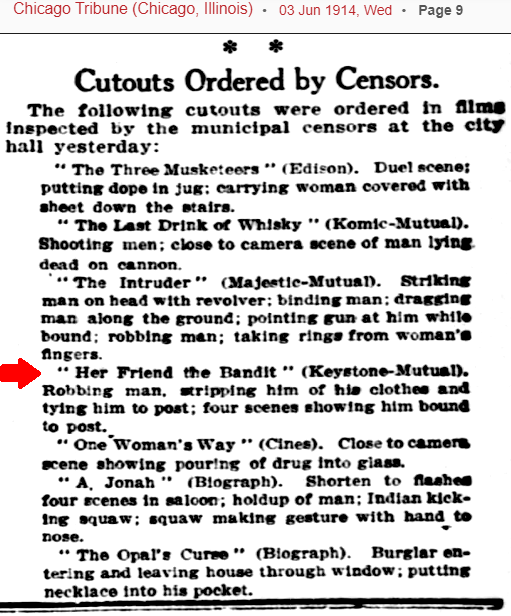

Now, let us look at what happens when the censors get hold of movies:

Though we have not seen any of the above seven movies, it is clear that the plots were removed by order of the censor board.

If prints of any of these films are recovered, I hope they will not be not be prints that were shown in Chicago!

The plot of Her Friend the Bandit has been summarized thus (Okuda and Maska, p. 43):

“Count De Beans [Charley Murray] is captured by a bandit [Charlie Chaplin], who assumes the Count’s identity

and attends a swanky party thrown by Mabel De Rocks. The bandit wreaks havoc

with the upper class until the police are called in to take him away.”

I wish I knew the source of that information.

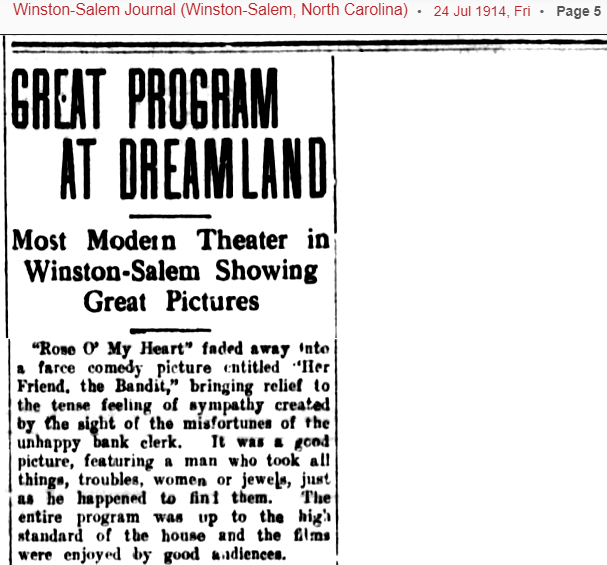

Now, let us check that plot summary against the announcement below:

This tells us so little.

The unfortunate bank teller, by the way, was Tom Santschi’s character in

Rose o’ My Heart,

a one-reeler

from Selig Polyscope, which I suppose is lost.

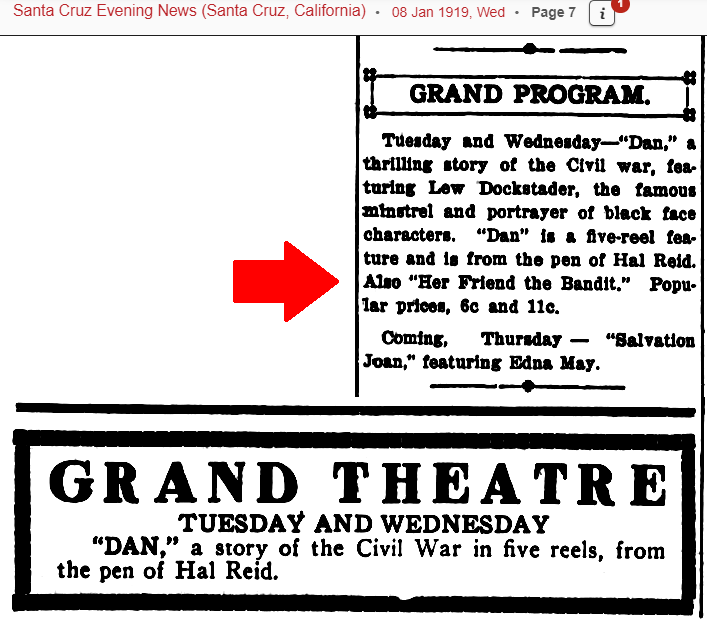

Below we find the final advertisement that is traceable, as of today, on the various online newspaper-archive searches,

and I can see that at least one other person searched this before I did and flagged it as being of interest:

So, we see that Her Friend the Bandit was still being shown, under that title, at least as late as 8 January 1919

at the mysterious Grand Theatre in

Santa Cruz CA.

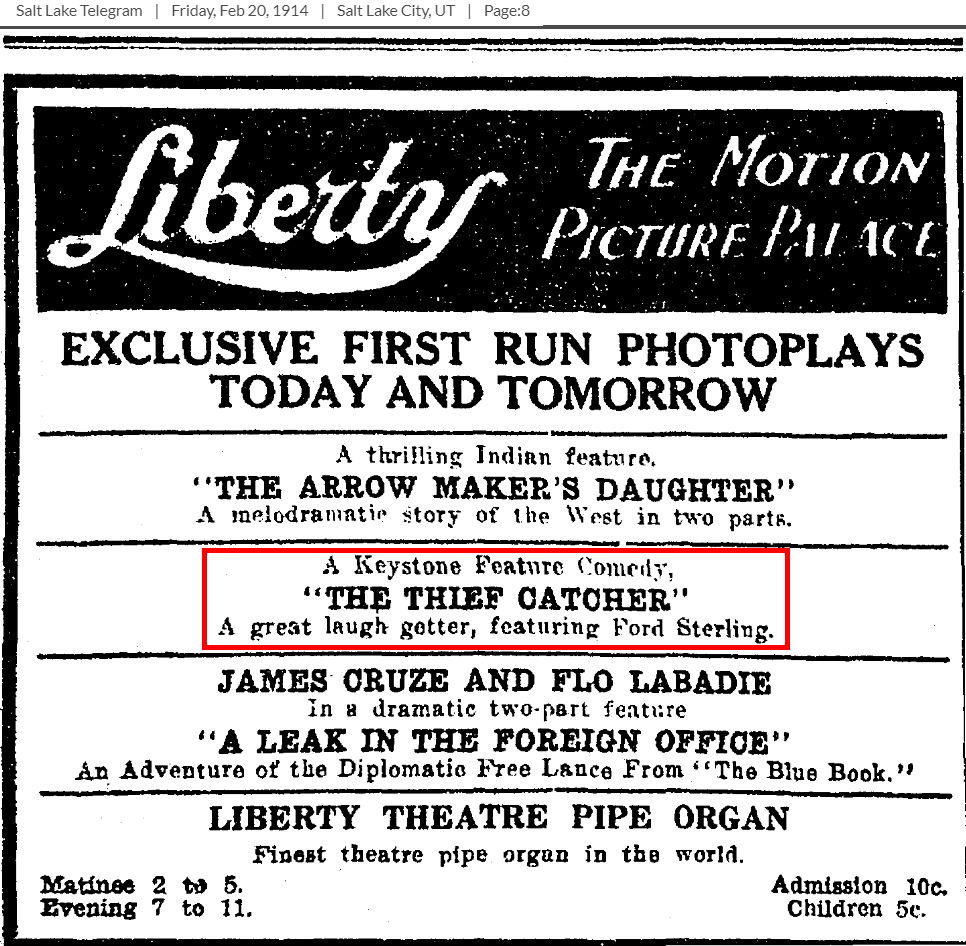

I have not read Harry M. Geduld’s Chapliniana (University of Indiana Press, 1987),

but I understand that it is he who claimed that Her Friend the Bandit

was reissued as

A/The Thief Catcher in 1915 and as Mabel’s Flirtation also in 1915.

Where he got that idea, I do not know. Perhaps I should grab his book someday and find out.

You will find

his supposition posted far and wide as verified fact.

Taking this as a lead, I decided to hunt for any online references to these two titles,

but what I discovered does not jive with the latest scholarship.

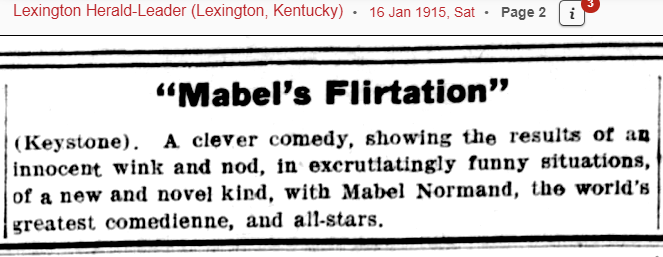

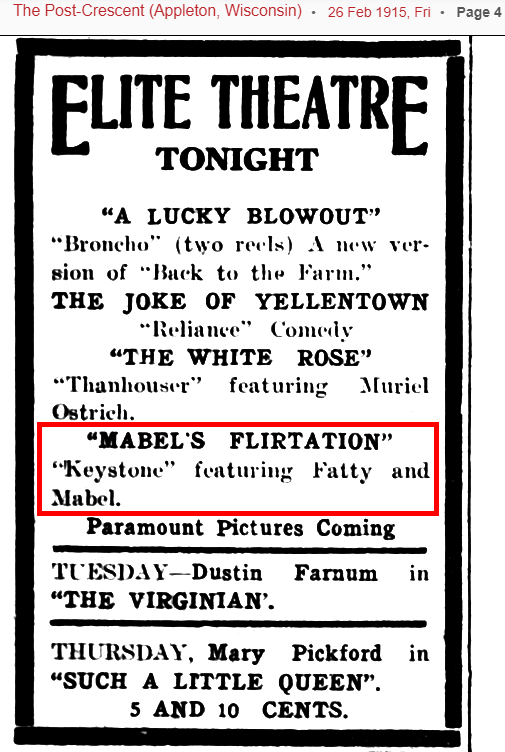

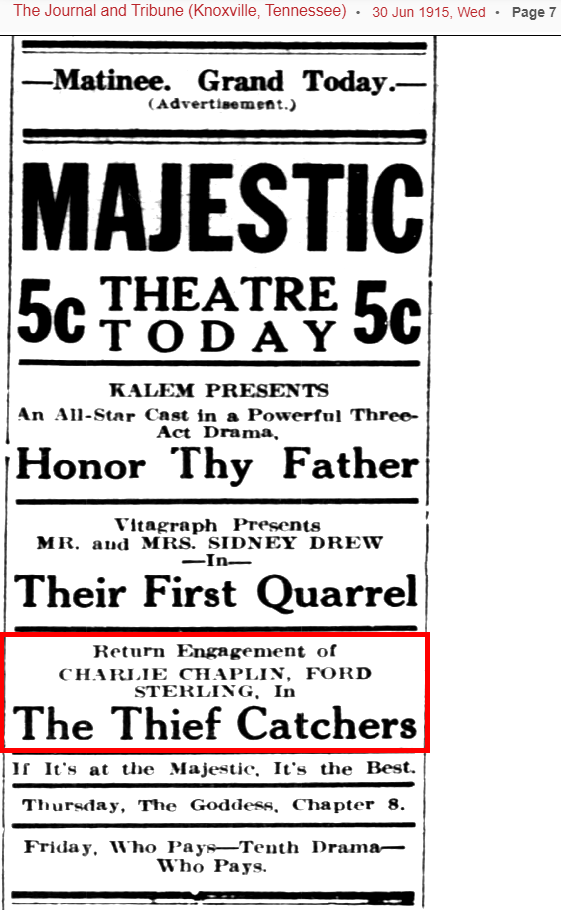

Behold:

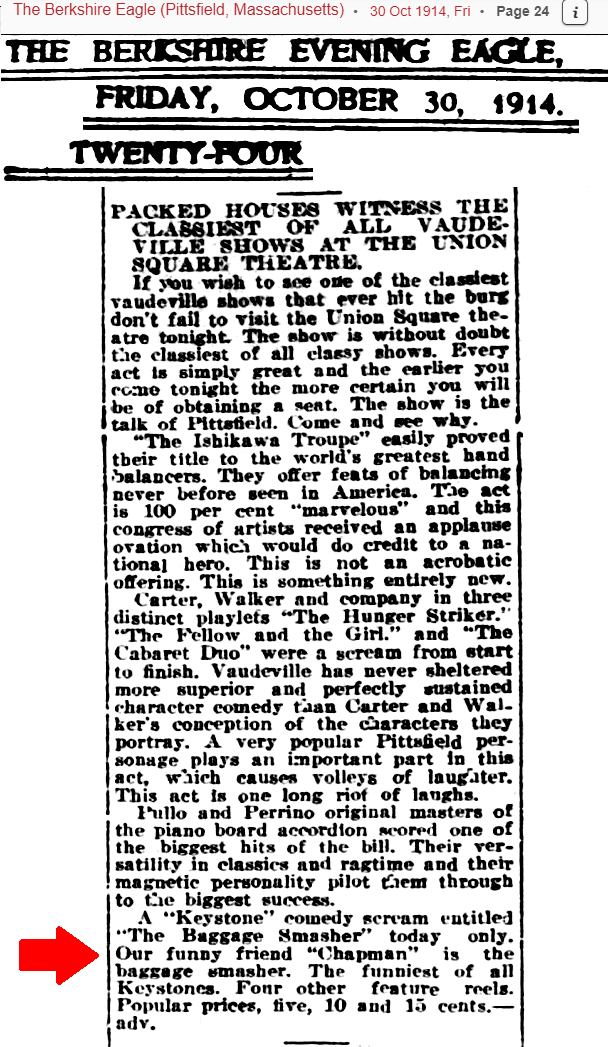

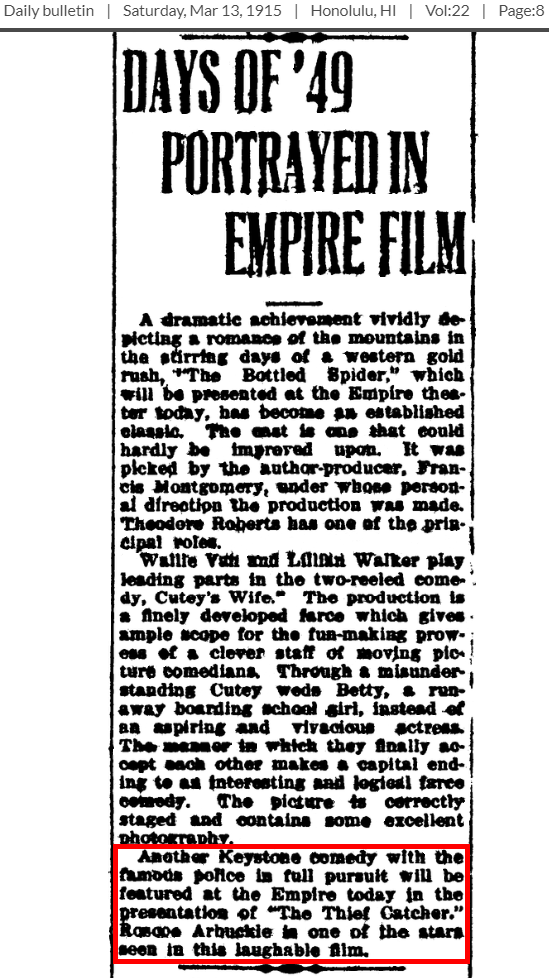

Above we see, definitively, that Mabel’s Flirtation has a different story and a different cast.

There is no mention of Charlie Chaplin or Charley Murray, but there is definitely a mention of Roscoe “Fatty” Arbuckle.

So, this is not a match.

What is Mabel’s Flirtation?

Is it a reissue of The Telltale Light?

Is it a reissue of A Misplaced Foot?

Or is it, perhaps, another movie altogether?

It is certainly not a reissue of Her Friend the Bandit, that’s for sure.

Unless someone can turn up evidence that two different Keystone comedies featuring Mabel Normand in 1914

(or the first two weeks of 1915) both went under the same title,

we can dismiss the claim that Her Friend the Bandit and Mabel’s Flirtation are the same film.

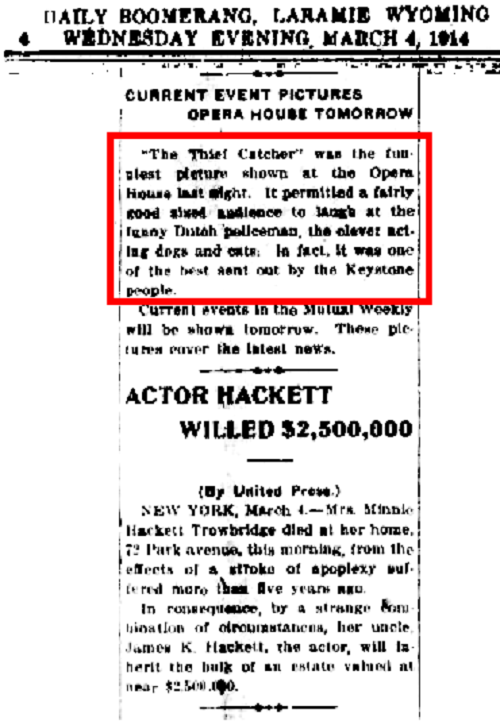

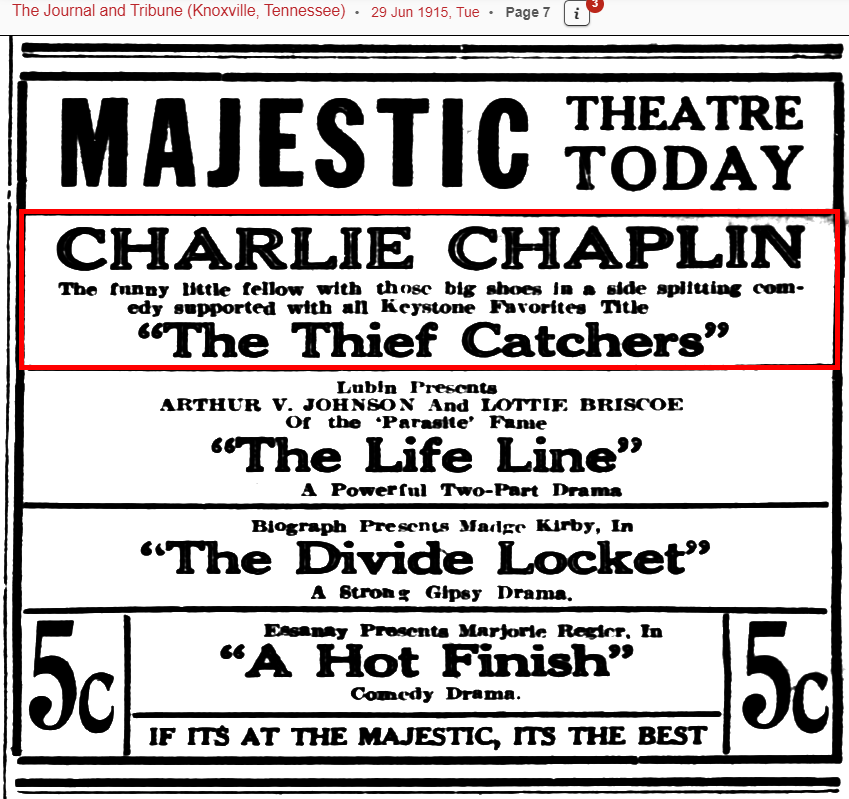

What about The Thief Catcher, though?

Paul Gierucki

recently discovered a 16mm print copied from a Tower Film Corporation reissue of

His Regular Job (former title: The Thief Catcher).

That is how we now know for certain that it is a Ford Sterling movie with Mack Swain and Edgar Kennedy

as well as a cameo by Charlie Chaplin as a Keystone Kop.

Paul is convinced that there was a typo in that reissue title, and that the former title should have been

A Thief Catcher, since The Thief Catcher was a different movie altogether.

(I am so far not having any luck in finding any announcements or advertisements for His Regular Job.)

Modern scholarship posits that The Thief Catcher is, in fact, a retitling of Her Friend the Bandit.

That got me excited, and so I spent some time on the various online newspapers to see what I could learn.

Alas, all I learned was that the compositors who set the cinema ads were remarkably lax about titles,

that they routinely switched “A” and “The” and made other mistakes besides.

A Thief Catcher was merely a misprint for The Thief Catcher, or vice versa maybe.

They were not two different movies, and neither title was a reissue of Her Friend the Bandit.

Now, this next one really does seem like an entirely different movie,

unrelated to A Thief Catcher and unrelated to Her Friend the Bandit.

My best guess is that the publicist who submitted this made a mistake and confused one movie for another: