|

Of course, you know that I’m lying.

I confess. What I wrote above is a lie, but not exactly.

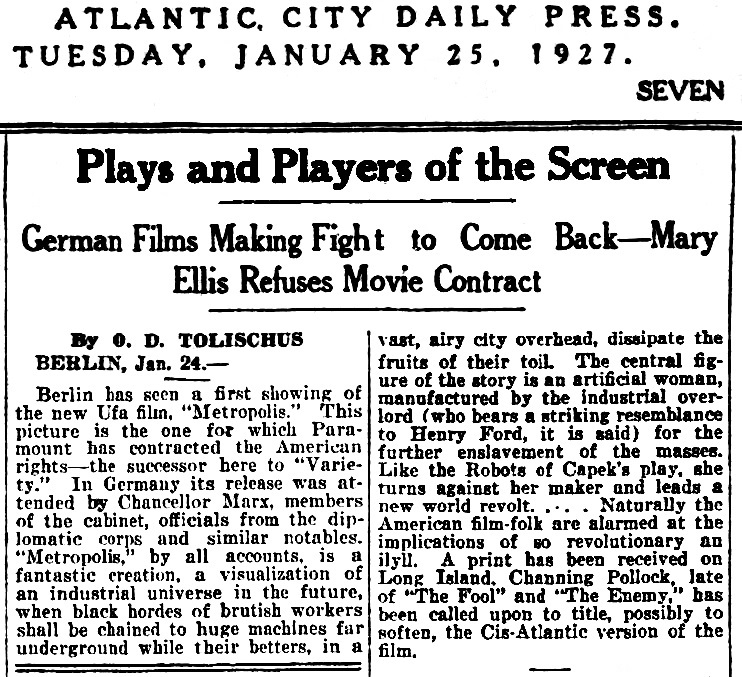

A few other foreign films reached these shores without Hollywood-imposed alterations.

That happened only because foreign distributors booked them here directly.

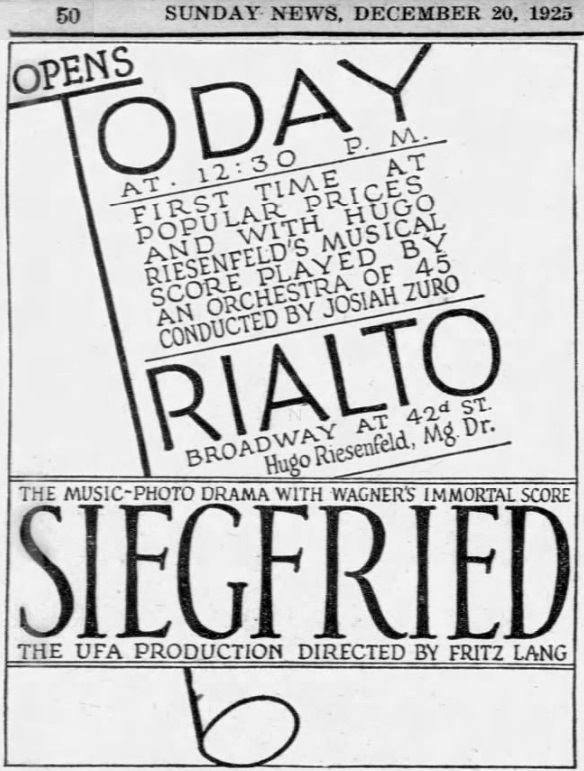

The Fritz Lang/Thea Von Harbou epic, Die Nibelungen, was shown in the US probably without alterations,

except that the second half was not shown at all.

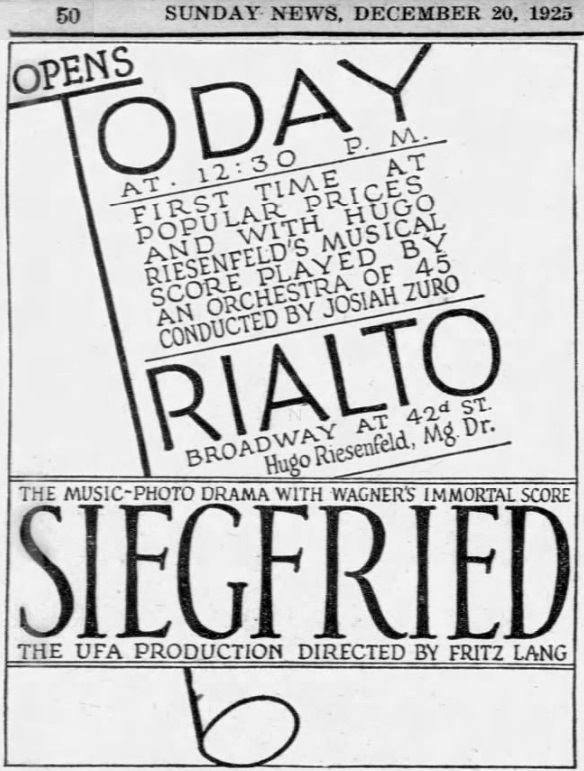

Only the first half, “Siegfried,” was shown here.

“Kriemhild’s Revenge” was dropped from the program,

which made for a lopsided viewing experience that left audiences hanging.

To get it shown in the United States, Ufa had to rent the cinemas itself:

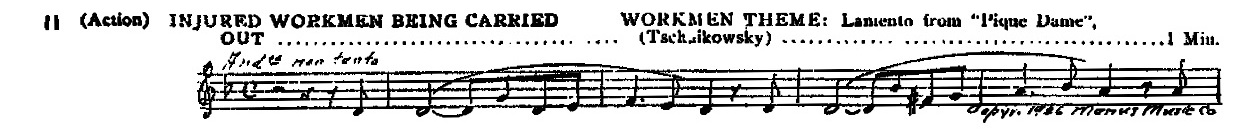

The Century and then the Rialto in Manhattan,

the Capitol in San Francisco, and

Philharmonic Auditorium (aka Clune’s) in Los Ángeles.

No Hollywood distributor wanted anything to do with it.

I suppose the same happened with a few other films as well.

Played through Saturday, 19 September 1925, a four-week booking.

One week, through 26 December 1925.

Played two weeks through Sunday, 29 November 1925.

Played six days through Saturday, 28 November 1925.

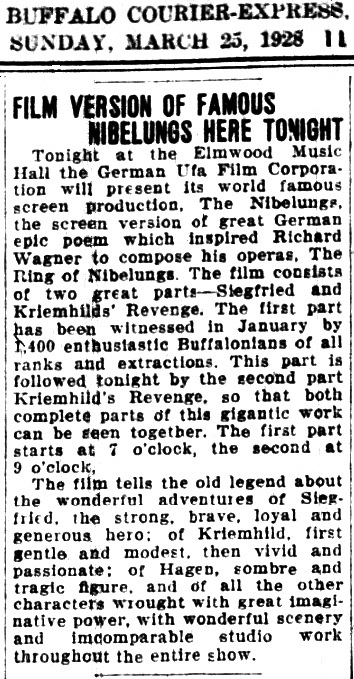

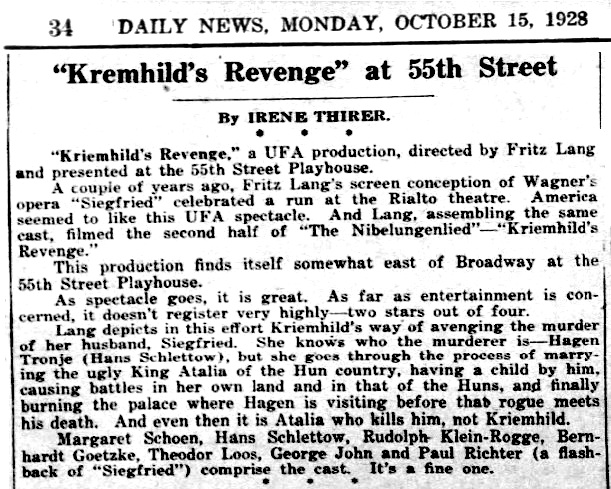

Well, it turns out that “Kriemhild’s Revenge” did arrive in the US after all,

a couple of years later, sometimes together with “Siegfried” and sometimes divorced from him.

Once again, this was booked directly by Ufa.

It got only a few bookings:.

The two movies also popped up at the Lyric in

Baltimore and at the Little in

DC in the spring and summer of 1928 and then at St. George’s Playhouse in

Brooklyn in November, at the Little in

Philadelphia in December, at the Little in

Buffalo in September 1929, at the Filmarte in

Los Ángeles in December 1929, at the Little in

Detroit in January 1930, at the Little in

Rochester in October 1930, at Scripps College in

Claremont in February 1931, and at the Stanford Assembly Hall in

Palo Alto that same month.

And that might have been it.

The Soviet Union bypassed Hollywood distribution by having its own distributor,

Amkino, release a few select Soviet pictures here,

but that resulted in only a few bookings, probably all at small off-the-beaten-path movie houses.

Shown here were the same editions shown in the USSR.

No Hollywood distributor would touch them.

As far as I know, these were the only Soviet silents shown here, and they got nearly no publicity:

| US première |

NYC Title |

| 12 Dec 1926 |

Armored Cruiser Potemkin |

| 11 Mar 1928 |

The Wings of a Serf |

| 17 Jun 1928 |

The Stationmaster |

| 28 Jul 1928 |

The Bear’s Wedding |

| 13 Oct 1928 |

Three Friends and an Invention |

| 02 Nov 1928 |

October |

| 17 Nov 1928 |

Mechanics of the Brain |

| 15 Dec 1928 |

Yellow Pass |

| 01 Feb 1929 |

Two Days |

| 11 Feb 1929 |

The White Eagle |

| 19 Feb 1929 |

Feat in the Ice |

| 15 Apr 1929 |

Prisoners of the Sea |

| 12 May 1929 |

Man with a Movie Camera |

| 07 Jul 1929 |

The Red Olympiad |

| 20 Jul 1929 |

In Old Siberia |

| 10 Aug 1929 |

The Power of Evil |

| 18 Aug 1929 |

Her Way |

| 07 Sep 1929 |

Seeds of Freedom |

| 16 Sep 1929 |

Moscow in October |

| 26 Oct 1929 |

Scandal |

| 09 Nov 1929 |

Arsenal |

| 30 Nov 1929 |

The New Babylon |

| 02 Dec 1929 |

Caucasian Love |

| 04 Jan 1930 |

Man from the Restaurant |

| 16 Jan 1930 |

Demon of the Steppes |

| 25 Jan 1930 |

Fragment of an Empire |

| 02 May 1930 |

The General Line |

| 24 May 1930 |

Turksib |

| 06 Jun 1930 |

Cain and Artem |

| 29 Jun 1930 |

Children of the New Day |

| 25 Jul 1930 |

Law of the Siberian Taiga |

| 06 Sep 1930 |

Storm over Asia |

| 17 Oct 1930 |

Earth |

| 28 Nov 1930 |

The Break-Up |

| 01 Dec 1930 |

Igdenbu |

| 03 Jan 1931 |

The Living Corpse |

| 17 Jan 1931 |

Father Frost |

| 21 Mar 1931 |

Transport of Fire |

| 03 Apr 1931 |

Cities and Years |

| 24 Jul 1931 |

A Jew at War |

| 18 Mar 1932 |

And Quiet Flows the Don |

| 19 Jun 1931 |

Black Sea Mutiny |

| 05 May 1932 |

The Earth Is Thirsty |

| 24 Aug 1932 |

Clown George |

| 21 Oct 1932 |

The Last Insult |

| 18 Nov 1932 |

False Uniforms |

| 10 Feb 1933 |

Jimmie Higgins (permitted only in private clubs) |

| 12 Feb 1933 |

Life Is Beautiful |

| 04 Apr 1933 |

Rivals |

| 05 Sep 1933 |

An Hour with Chekhov |

| 29 Oct 1933 |

Three Thieves |

| 18 Feb 1934 |

Motele the Weaver |

| 29 May 1934 |

Mother |

| Canceled? |

Judas |

The advantage of having a foreign company release foreign films in the US: The films can be shown in the US.

The disadvantage of having a foreign company release foreign films in the US: The films can only barely be shown.

Since the above films did not have Hollywood sponsorship, they had probably fewer than five brief bookings each.

Why the Kremlin insisted that Amkino continue its activities in the US, I have no clue —

unless it was a convenient cover to collect intel?

So, while Hollywood was flooding foreign markets with its own films,

it was not permitting foreign films to get more than the smallest exposure in the US.

The German studios were constantly trying to break through that impasse, to no avail.

Now we run into a contradiction.

The idea that Paramount insisted upon shorter movies is ludicrous.

Paramount at the same time was releasing Wings, which was the same length as Metropolis.

United Artists’ The Thief of Bagdad was the same length.

MGM’s Ben-Hur and The Big Parade were the same length.

The list goes on.

So the idea about movies needing to be reduced to standard length holds no water.

Yet Paramount reduced the movie to standard length.

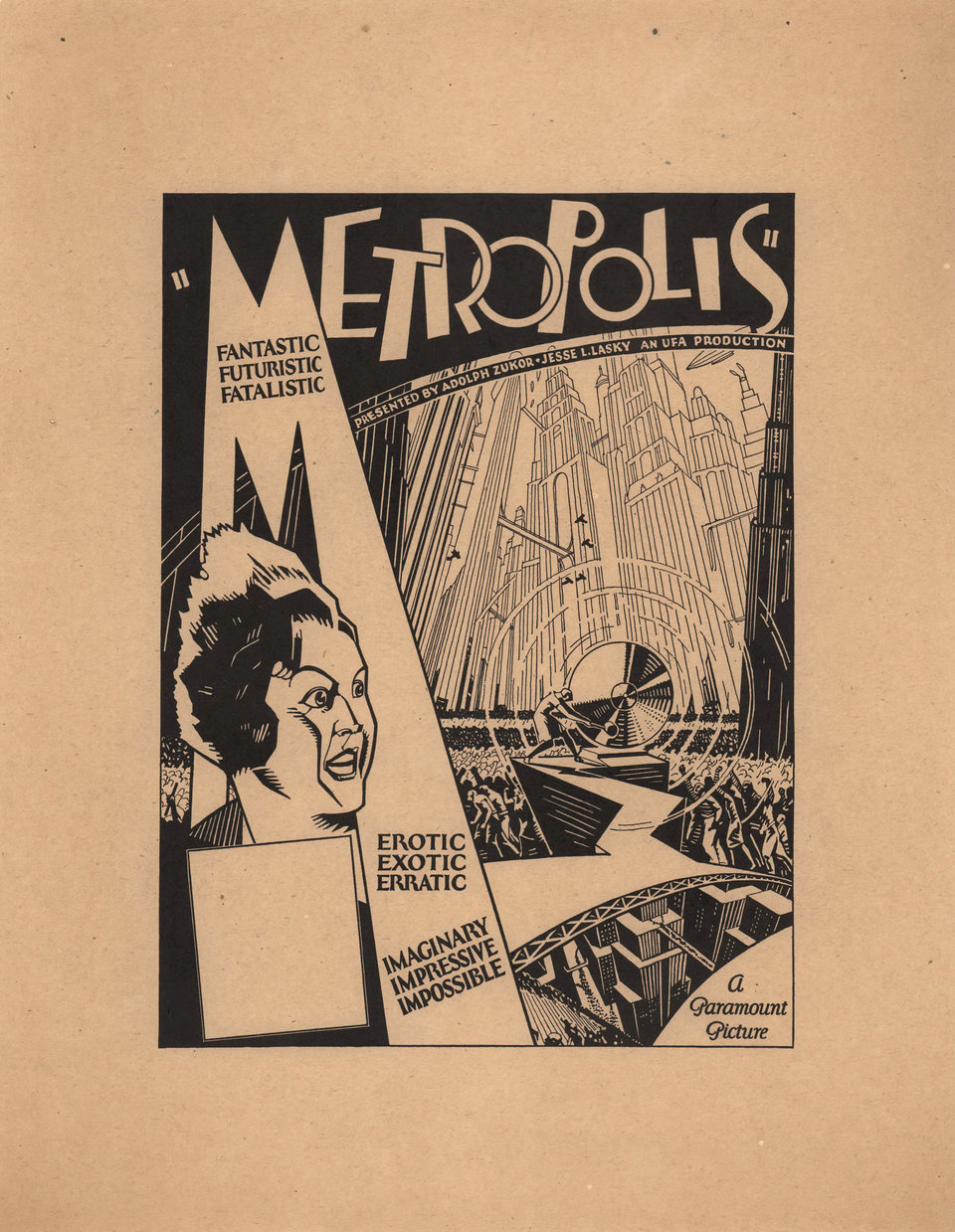

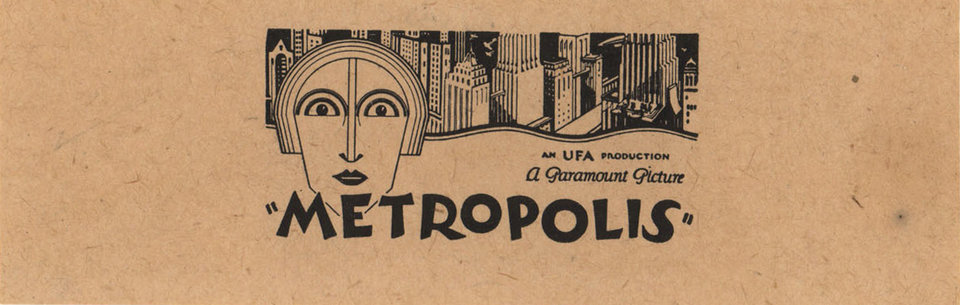

Ufa, spending Paramount’s money, had produced a specialty item.

Paramount amputated the specialty away and left merely a crippled item.

Then Paramount’s parent company, Publix, decided it wanted a standard programmer instead,

suitable for a continuous-show (grindhouse) policy.

So, though Paramount and Publix were perfectly okay with specialty items running two and a half hours,

some bureaucrats decided, effectively, “Yeah, that’s a great idea —

for us, not for foreign competition.”

Here’s a similar thought.

Paramount had paid (in full?) for the production of Metropolis and definitely wanted a return on its (probably) $190,500 investment.

On the other hand, Hollywood was busy making its own massive epics,

such as Wings and The Thief of Bagdad and Ben-Hur and The Big Parade, mentioned above,

all of them pretty dumb but visually stunning.

Metropolis would easily have given the Hollywood epics a run for their money.

In terms of plot, it was just as silly as its American counterparts,

but it was made with enough panache and bravado and sincerity to rise above the level of its Hollywood rivals.

Hollywood’s goal in usurping European bosses was to ensure the primacy of Hollywood product in the marketplace.

So, Paramount was endeavoring to achieve two contradictory goals:

Get a return on its Metropolis investment by booking it heavily,

but ensure that it draws no attention or sales away from Hollywood product.

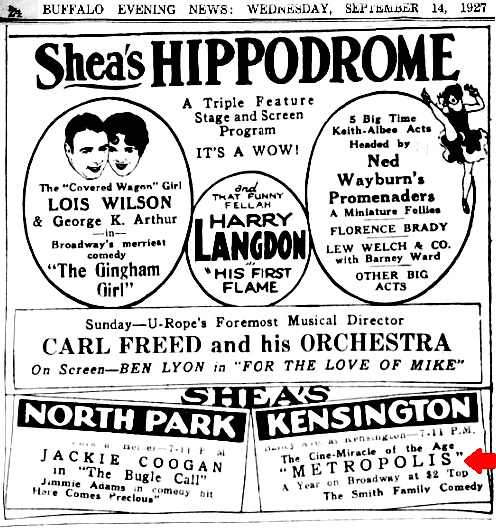

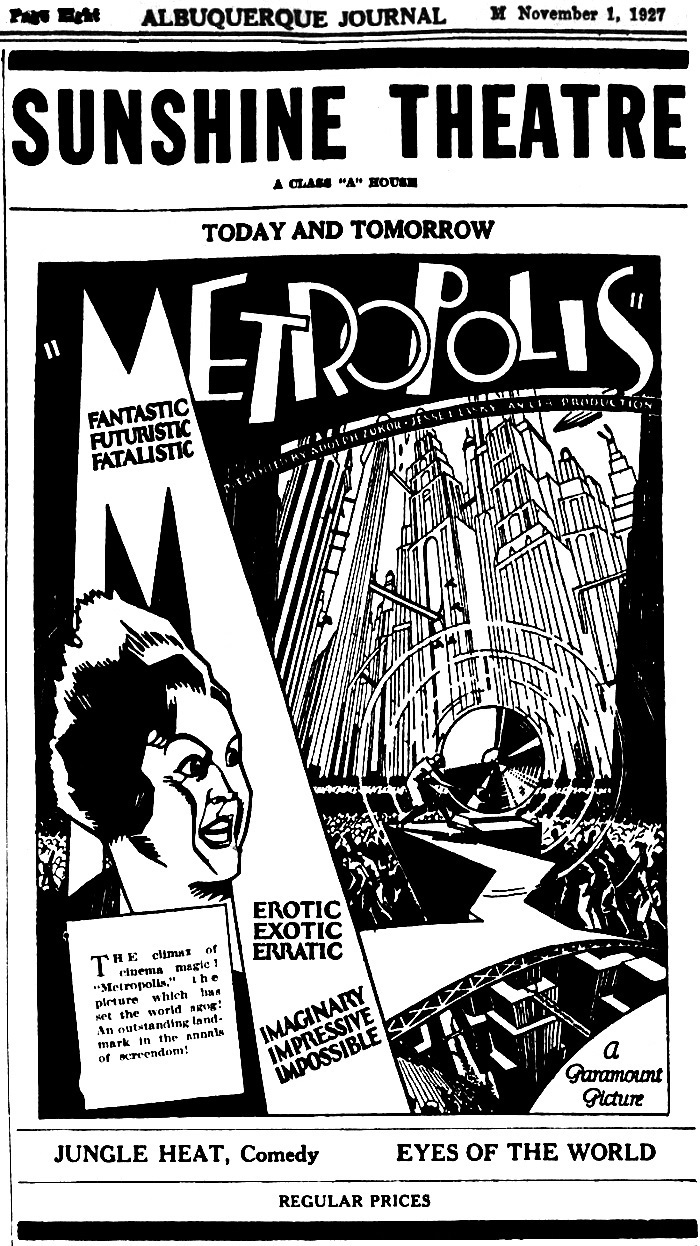

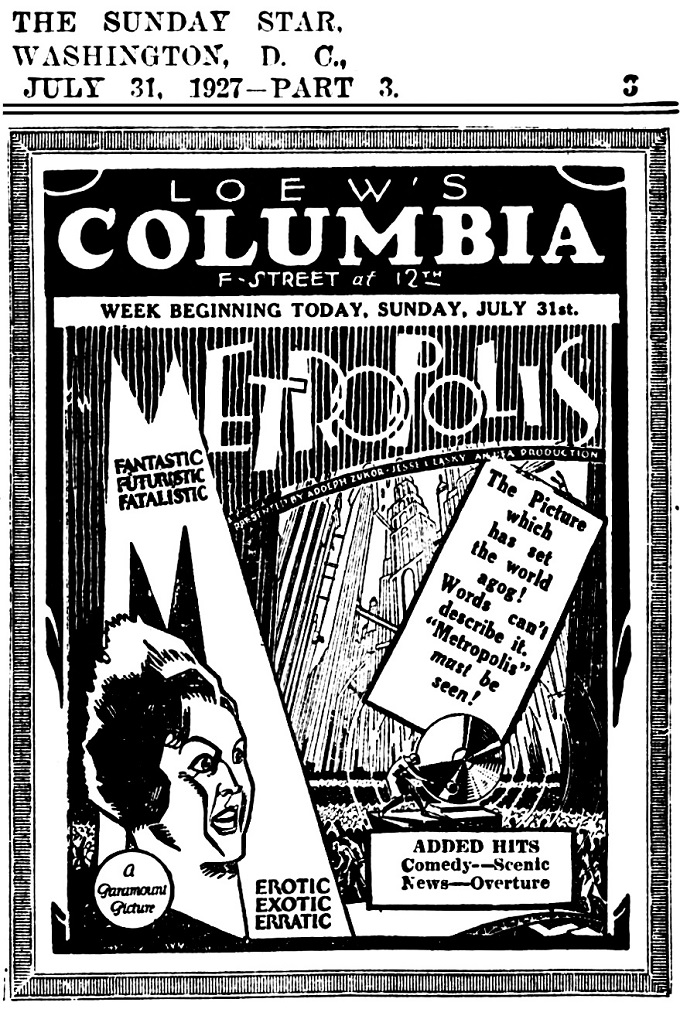

So, by means of massive cuts and overspeeding (105'/min. = 28fps),

and putting it on double bills with Hoot Gibson westerns and vaudeville acts,

Paramount converted a monumental and overpowering epic into a dinky little 75-minute quickie to pass the time.

They crippled it enough to nullify its artistic impact but not enough to nullify its market value.

This, I suppose, more than anything else, was the goal.

When you try to crack a case,

look at what the parties did, look at what they went far out of their way to do,

look at what they consistently went far out of their way to do,

look at the consistent results of their activity,

and you have likely reasoned out the motive.

So, I think this is the explanation.

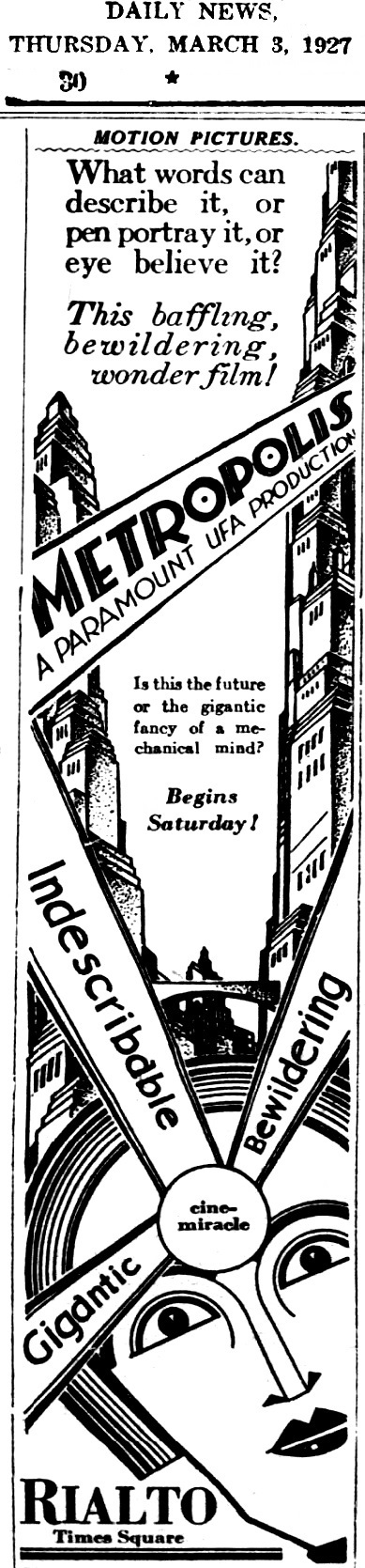

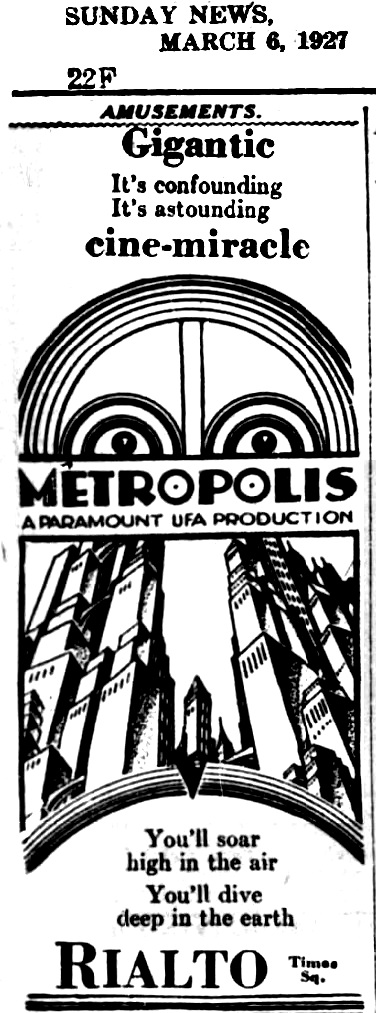

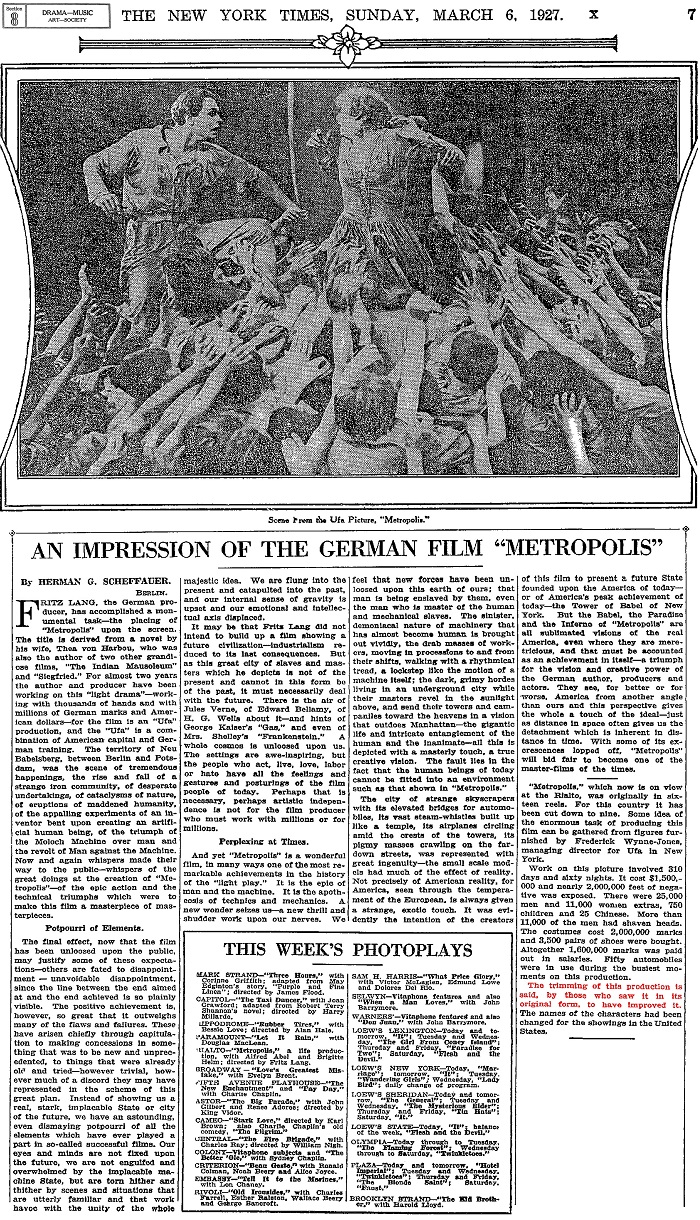

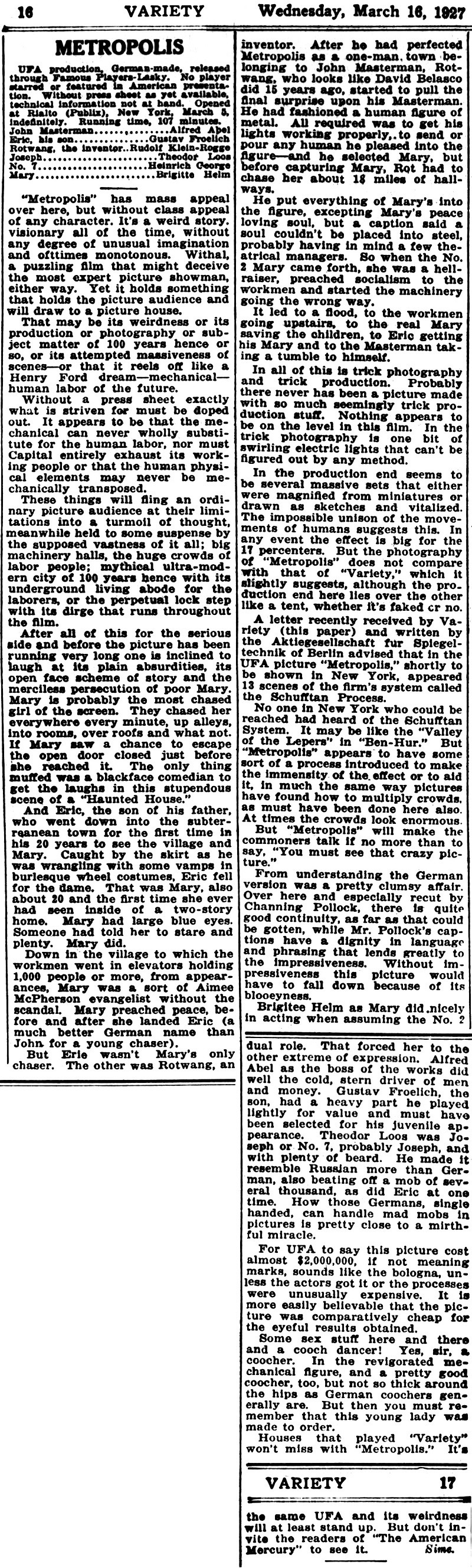

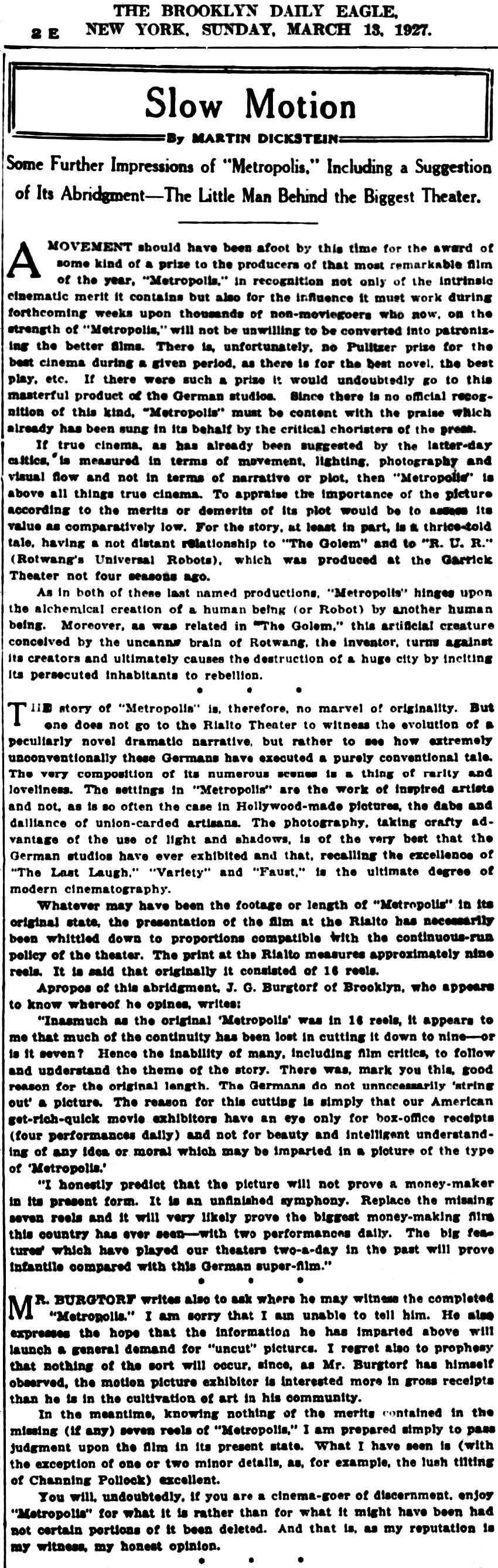

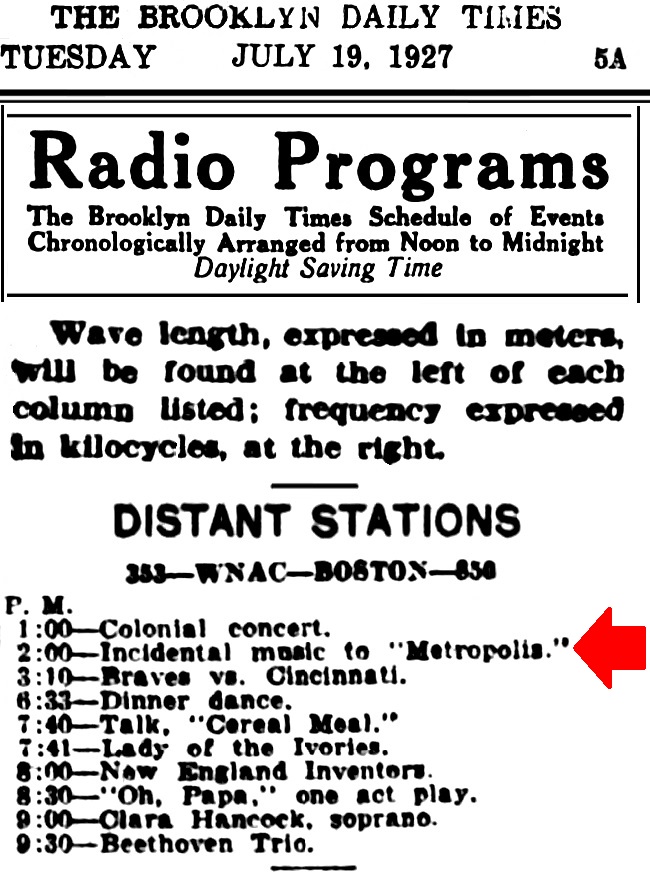

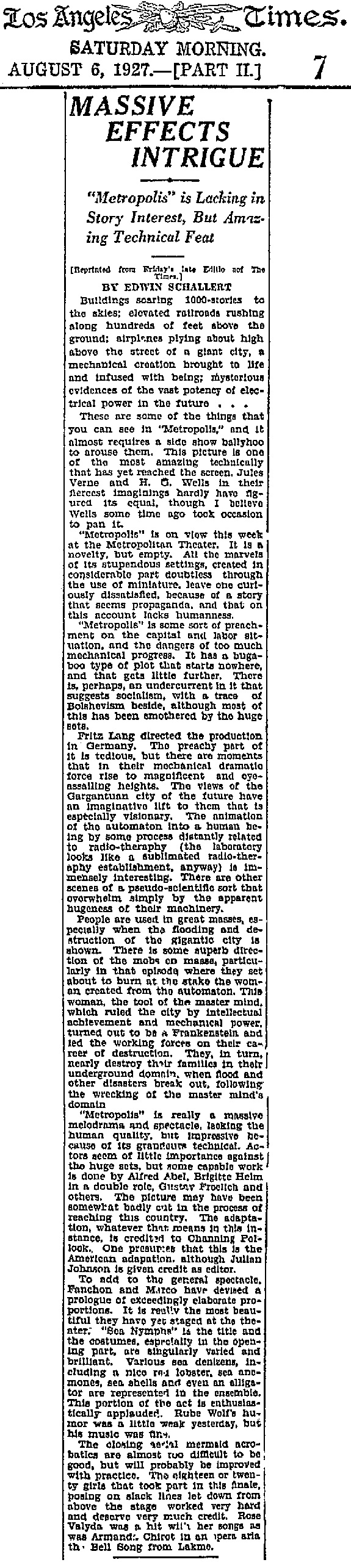

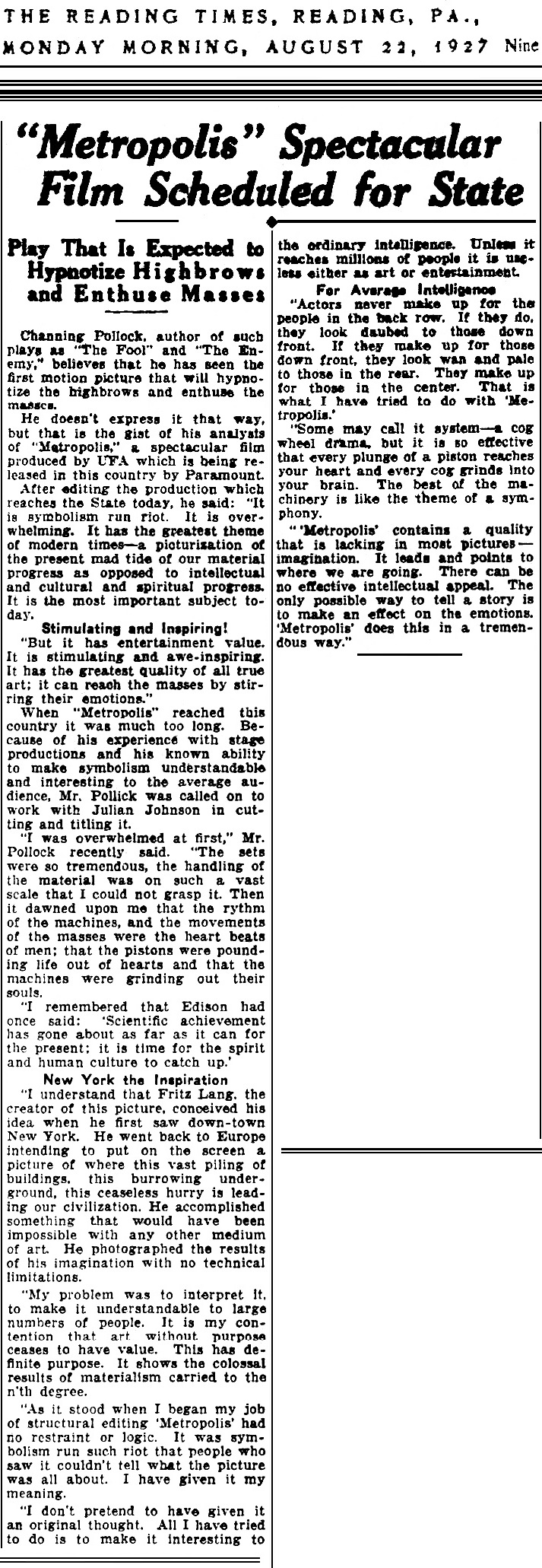

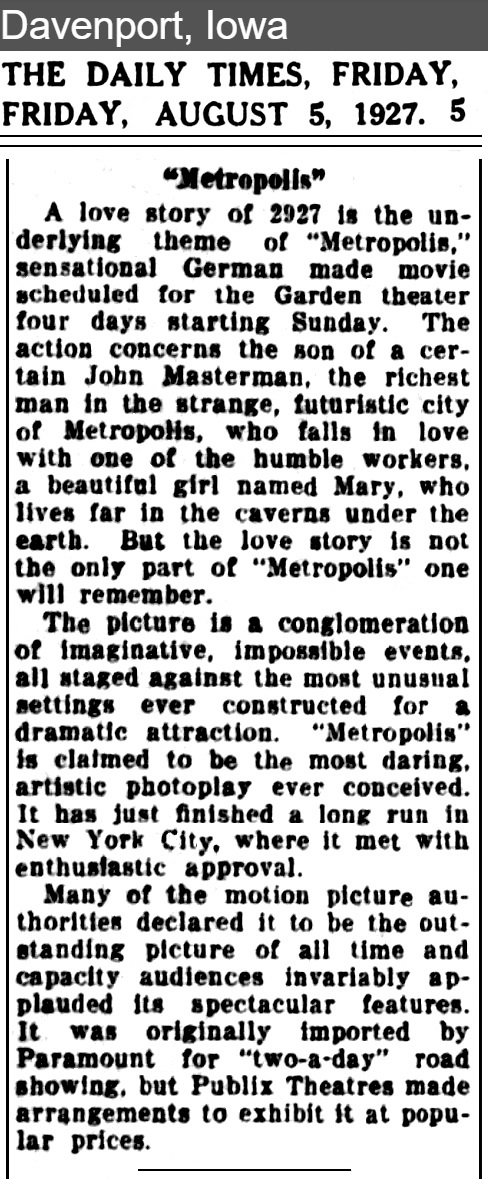

Below is a press release that began to circulate about the time the movie first opened in early March 1927.

I cannot find the original printing, and some newspapers abridged it.

Below is probably the complete press release, reprinted several months later.

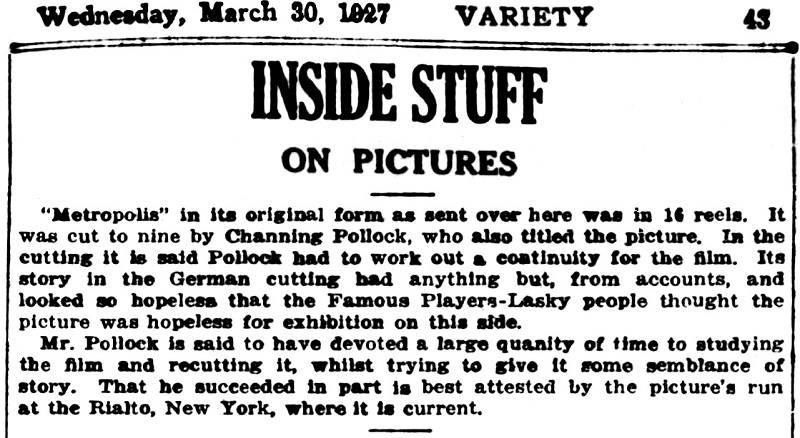

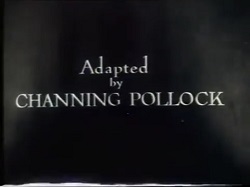

Pollock was not the editor.

He watched the movie six times, on a small screen, in dead silence,

with only a stenographer by his side and a push button by which he could tell the projectionist to pause the film.

He took some notes and spent a few days telling Julian Johnson, Edgar Adams, and their editing crew what to do.

Then he went back home with a much fatter wallet.

Remember, what we have above is a press release, and it is a bad idea to believe a press release.

We do not know if Channing made the statements attributed to him,

but I suppose he said something to their effect.

Even if it was a staff publicist who invented his quotations,

we can nonetheless see from the press release above that Channing didn’t understand the movie at all.

That is even more clear when we watch his abridgment.

He tried “to make it interesting to the ordinary intelligence.”

Say what?

I do not know what “ordinary intelligence” means.

Intelligence is a nebulous concept, and nearly everybody I have ever met

is extraordinarily intelligent in a few areas, extraordinarily unintelligent in a few other areas, and generally bumbles through life.

That’s what I do, bumble, nothing better.

I would not know how to cater to “ordinary intelligence,”

and I certainly would not know how to pander to it.

No play, no movie, no book, no musical composition, no recipe, no landscape has universal appeal.

We are each of us the product of our upbringing, our environment, our society,

as well as of our own innate and in many ways immutable individual thought patterns.

What speaks to one of us will leave many or most others cold and baffled.

Again, that’s just the nature of the beast.

It is impossible to retool Metropolis to give it broader appeal.

Its appeal could certainly be narrowed, though, narrowed by slashing.

What was Channing attempting to do?

Was he trying to simplify a movie that, at its surface level, was already quite simple-minded?

It was a hit in Berlin and ran to packed houses for four months.

It had been shown in several other European countries, too, and I suppose it did well, though I do not have any data, unfortunately.

Was the Berlin run, by itself, not sufficient indication of popular appeal?

Was Channing trying to hammer the film into his own idealistic framework?

My guess is that we would be wrong to search about for higher goals.

Channing was simply drooling at the massive paycheck and he would do anything at all to earn it.

Would he have been happy if another writer were to treat his own plays in a similar fashion?

Did he care?

By changing the characters’ names and by rewriting the titles,

he attempted to Americanize a distinctly German work.

Americanizing a foreign work is invariably awkward and ruinous, unless it’s done as a joke.

Broad Appeal. Let us ponder Broad Appeal for a moment.

Let us perform a thought experiment.

You are all familiar with

Dvořák’s Sixth Symphony, yes?

Suppose Victor Records had decided to issue this symphony,

but that its executives were worried about Broad Appeal.

So they ordered their staff to cut the symphony down to two and a half minutes

and to have it performed as a foxtrot with lyrics by Will Marion Cook.

Satisfied with their result, the executives then had the only copies of the full score tossed into the incinerator.

Would that give it Broad Appeal?

No artist knows if his piece works until it is tested with an audience.

Fritz was notorious as an obnoxious madman, a persona he maintained only at the studio,

yet the artist in him remained receptive to suggestions, always.

If changes were needed, he would have been open to listening, pondering, pitching in.

He would always agree with an intelligent criticism, and he would uncomplainingly make adjustments.

If Channing had good ideas for altering the film,

Fritz would have listened attentively and the two could have, would have reached an agreement.

It is apparent that Channing never reached out to Fritz.

Perhaps he was told not to.

Since he agreed to alter someone else’s work without involving the original creator,

well, my respect for him takes a nosedive.

That is an offense I simply cannot abide.

This new main title was created by a staffer at Paramount

Pictures for the US release. This appears on a YouTube video,

and so it was either taken from Reg Hartt’s 16mm print or

it was taken from another print of the US edition. I wish I

knew which. If there’s a print other than Reg’s,

we must locate it!

|

So, following Channing’s ideas, the editing crew shortened the movie drastically, changed the characters’ names,

changed the plot, rewrote the titles, and rearranged the scenes.

The elimination of the rivalry over Hel,

the elimination of Georgy’s adventures in the limo,

the elimination of Der Schmale’s visit to Josaphat’s flat,

the elimination of the monk,

the elimination of Der Schmale’s transformation into the monk,

the elimination of the fight between Joh and Rotwang,

the elimination of the lynch mob mistaking the real Maria for the imposter,

denuded the story of its coherence and discarded more than half of its entertainment value.

At Channing’s suggestion, the editing crew also added a prologue, an embarrassingly bad and corny prologue:

NO SOUND

This is how his prologue appeared in Australia and therefore in the export edition.

It was probably identical in the Paramount/US edition, but I can’t be certain of that.

That painfully awful prologue colors everything that follows

and thereby distorts the audience’s perception of the film.

It is clear, more than obvious, that Channing Pollock entirely misunderstood the movie.

He was blind to the allegory.

He misunderstood the plot.

He misunderstood the symbolism.

He did not understand that the movie was a deliberately ludicrous satire.

He misunderstood the comedy as drama.

He misunderstood everything, everything, everything.

Metropolis is not a difficult story.

When viewed without knowledge of its didactic agitprop socio-political purpose, it comes across as

a ridiculously stupid story.

Yet Channing Pollock had difficulty following even a simplistic story.

His attempt to streamline the movie managed only to twist it and cripple it.

I’ve not seen Channing Pollock’s plays,

but if he wasn’t even intelligent enough to understand something so childishly simple as Metropolis,

I can only wonder about his gifts as a playwright.

I suppose his plays are unendurably bad.

I could be wrong about that.

Life is full of surprises.

Randolph Bartlett? Who the heck is

Randolph Bartlett?

This Randolph Bartlett reminds me of a book publisher and also of a movie producer under whom I unfortunately labored,

who did their utmost to ruin everything they touched, because were convinced that they were smarter than the authors

and that they were rescuing hopeless disasters.

This Randolph Bartlett complains about how the German films in their original forms were “extremely naïve,”

but yet the Hollywood revisions made them far more naïve, not less.

By the time the editing crew completed incorporating Channing Pollock’s suggested changes into the film,

the result was about 3,170m, or about 10,400'

assembled onto 12 reels.

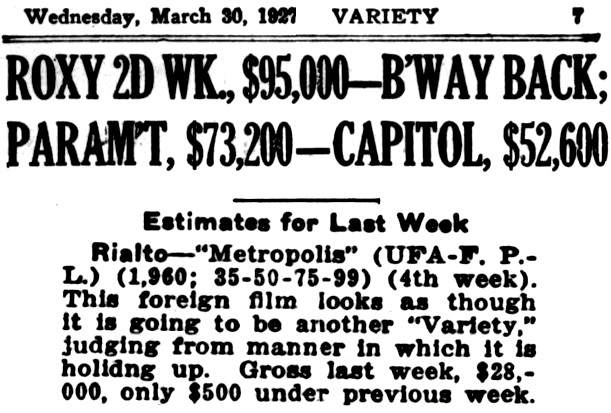

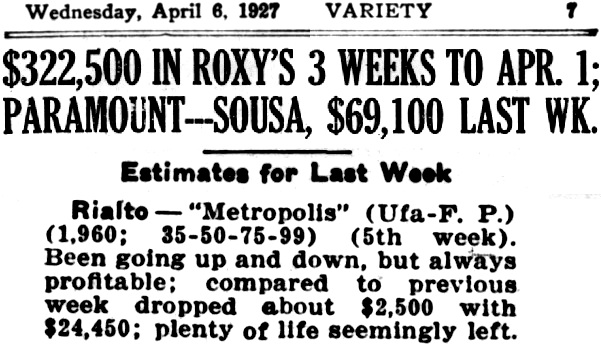

The common claim, then and now, is that this 10,400' edition roadshowed at the Rialto in Manhattan.

At the preferred projection rate of 97.5'/min. (26fps), it would have lasted 107 minutes.

Yet that is not what happened.

Not at all.

The claim is wrong. Wrong. Totally, totally wrong.

That is NOT what played at the Rialto.

In truth, the print that premièred at the Rialto was a mere 8,039'.

We have no documentation that would explain why.

We have no evidence that would explain why.

We have no rumors that would purport to explain why.

All we know, and we know it for certain,

that Channing’s edition was about 10,400' and that the première print was 8,039'.

So, we have Step A and we have Step C, but we do not have Step B.

Step B would explain why Channing’s version was reduced a further 2,400' or thereabouts.

Though we do not know, though we do not have documentation,

there is only one possibility:

The Publix executives ordered Paramount to trim the film to 8,000' or thereabouts,

to fit its standard programming schedules.

Any idea that Metropolis was a specialty item for a specialty audience that needed specialty handling was now entirely jettisoned.

A ha! Found it! The evidence! I found it. I wasn’t even looking for it, but I found it! Yay!

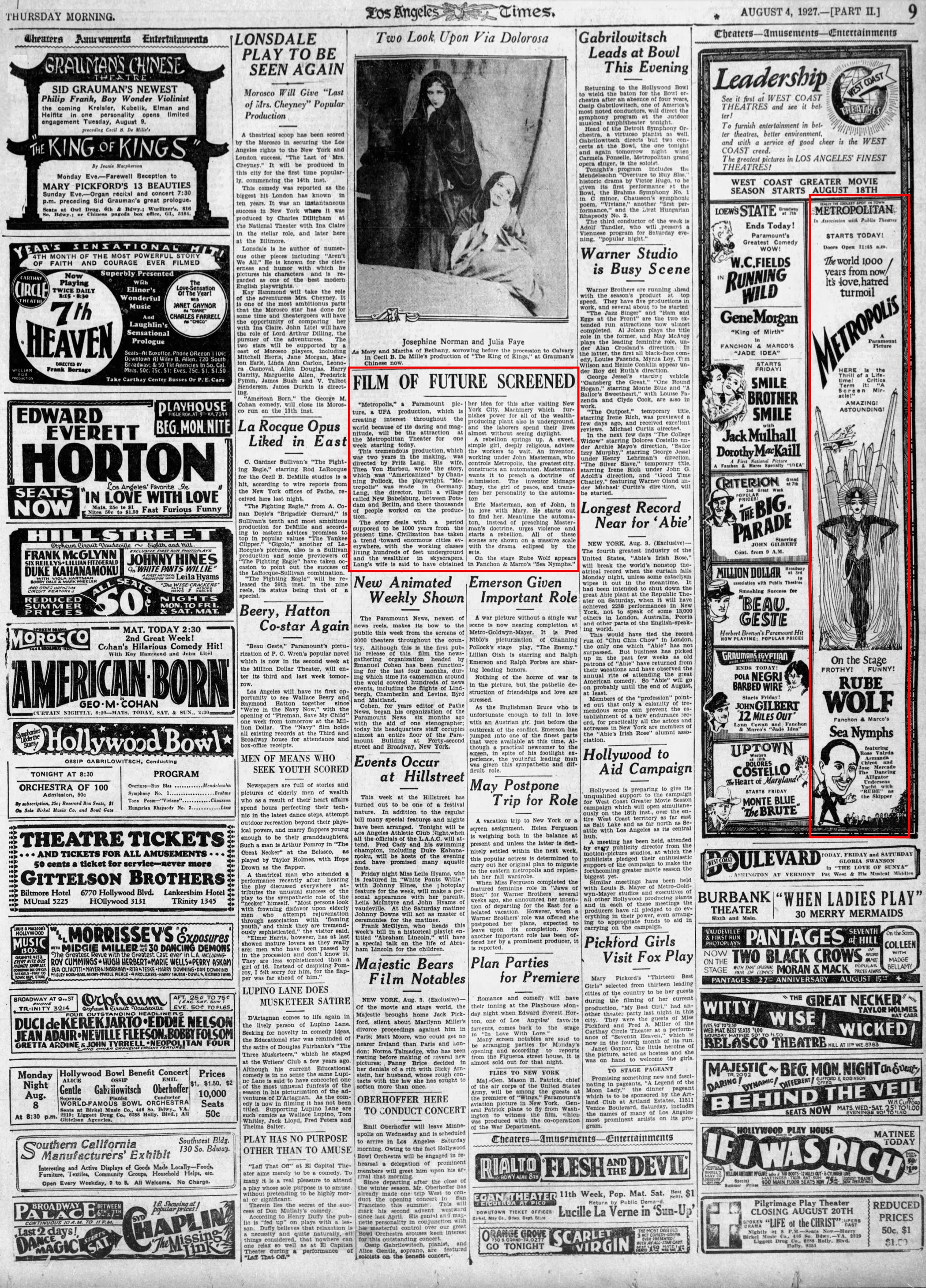

Let us take a look at a rival press release below.

It is the oddest press release I have ever seen, because it makes a confession:

See? Told ya.

This entirely unorthodox press release was also published in The Montgomery Advertiser,

Monday, 19 September 1927, p. 7.

I have not run across it anywhere else.

I suppose it was issued when the supervisor was out on vacation

and I suppose it was withdrawn as soon as the supervisor returned and read it with horror.

Note what it says:

Metropolis “was originally imported by Paramount for ‘two-a-day’ road showing,

but Publix Theaters made arrangements to exhibit it at popular prices.”

The copywriter who typed that up and shot it out over the wire service was out of a job a few days later.

A press agent should realize that nothing should be mentioned about any changes,

but that if, for some reason, there is a compelling legal need to make a mention about changes,

then the statement should simply be that Paramount and/or Pollock adapted it from the German original, reducing it from 16 reels to 9.

That is all. Nothing more.

This press release, on the other hand, revealed a bit about boardroom politics.

Terminable offense.

But I’m glad. I feel vindicated. Hoorah.

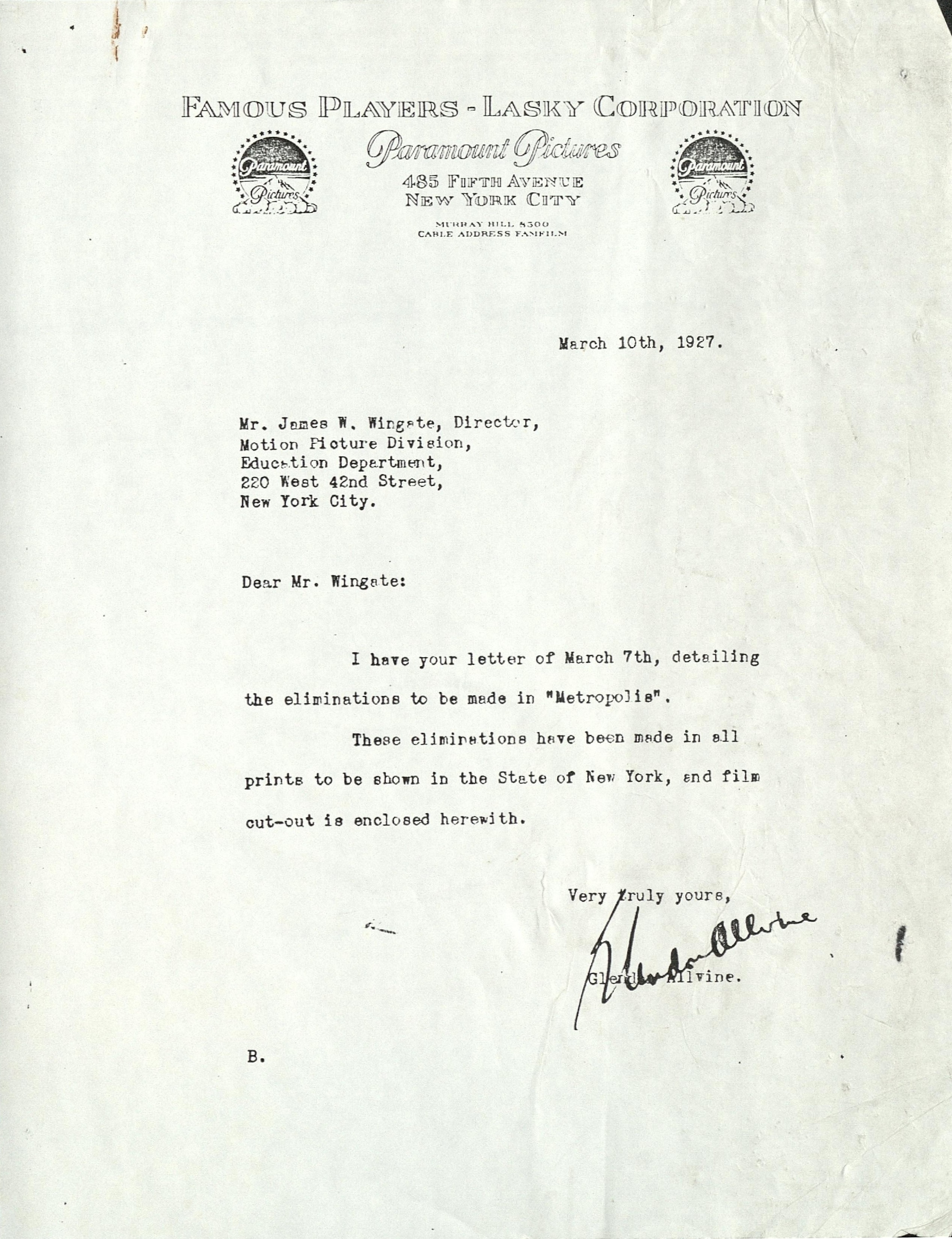

On the “Classic Horror Forum” chat group, we discover that Steve Joyce (“Barbenfouillis”), in a post from 16 March 2023,

recently ordered copies of items from the Forest J Ackerman archive,

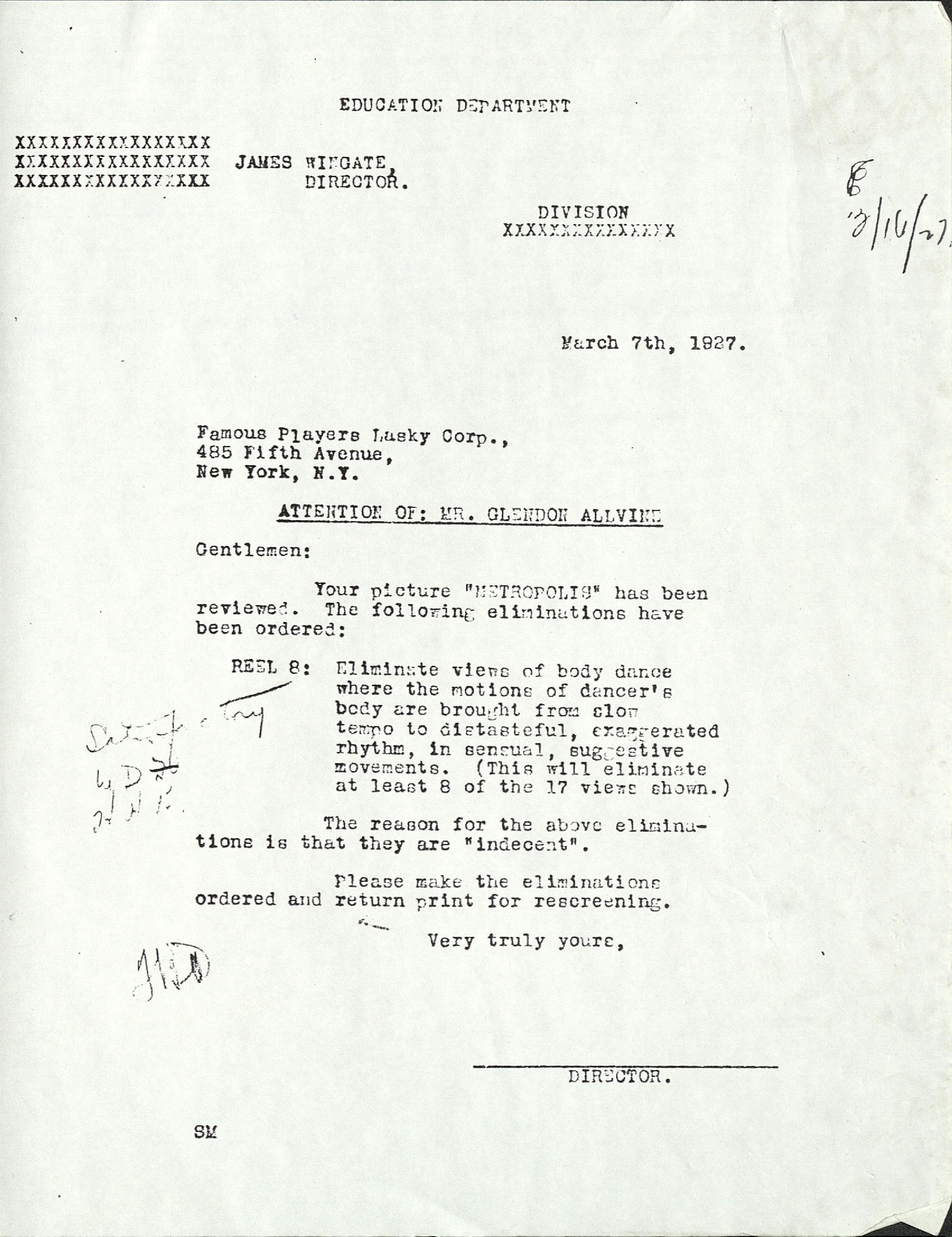

and these include this fascinating quote from the local NYC censor board:

|

March 7 1927 Letter to Famous Players Lasky: Gentlemen, Your picture “METROPOLIS” has been reviewed.

The following eliminations have been ordered:

Reel 8: Eliminate view of body dance where the motions of dancer’s body are brought from slow tempo

to distasteful, exaggerated rhythm, in sensual, suggestive movements.

(This will eliminate at least 8 of the 17 views shown.)

The reason for the above eliminations is that they are “indecent”.

Please make the eliminations ordered and return print for rescreening....

from James Wingate, Director

[on another page identified as director of The Motion Picture Division, Education Department, 220 West 42nd Street, New York City.]

~ a fellow named Glendon Allvine made the changes and re-submitted them within days.

|

That was not in Reel 8, by the way.

It was at the end of Reel 6, and definitely not in Reel 8.

Except that it was in Reel 8.

Paramount mistakenly sent the censor board a leftover print of the 12-reel Channing Pollock edition

rather than the 9-reel release edition.

Why did Paramount send out a 9-reel release edition to the Rialto

but a 12-reel pre-release edition to the local censor board?

Because the editing department and the shipping department and the publicity department were three different departments,

and they probably ate in different corners of the commissary.

That’s why. Simple as that.

It is clear that the 8 shots (probably about 12 or 15 feet, or eight seconds) were deleted not in just this one print, but in all US/Canadian prints.

The order was made on 7 March, and the eliminations were made that day,

and the deleted footage was sent to the censor board that very day,

which was TWO DAYS AFTER the film opened.

The audiences who saw the film those first few days saw a few extra seconds.

By 8 March, that footage was physically chopped out.

This topic comes up again 27 years later, as we shall see.

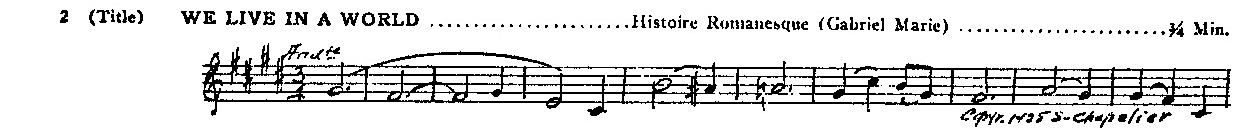

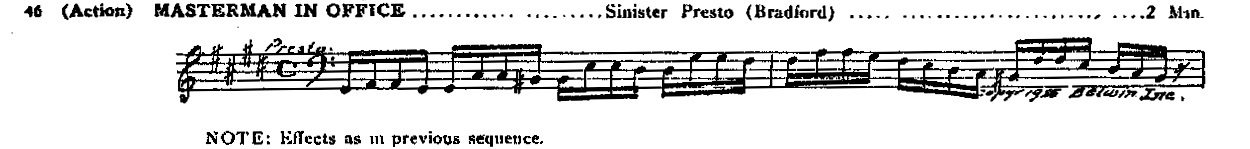

The print that opened at the Rialto was 8,039 feet mounted onto nine reels,

soon reduced to about 8,025' more or less, supplied with

James C. Bradford’s music cues,

which probably no accompanist bothered much with.

Cinema musicians preferred to assemble their own cues,

and many piano and organ soloists just played the films cold.

Now, Rod Sauer is one of those people who just makes me want to wither into nothingness.

He is what I wish I had been, but I wasn’t, I didn’t, I couldn’t,

and so I just witness his work with a mixture of frustration, envy, and awe.

My life simply took that wrong left toin in Albuquoique.

He authored a lovely article,

“Silence Gets Sound,”

in which wrote he:

|

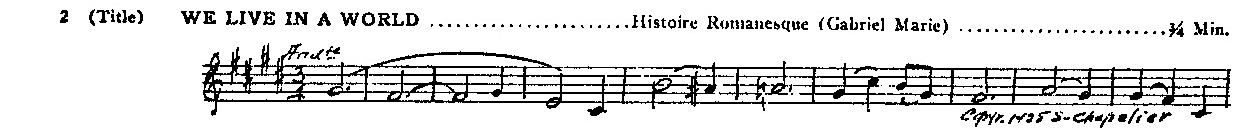

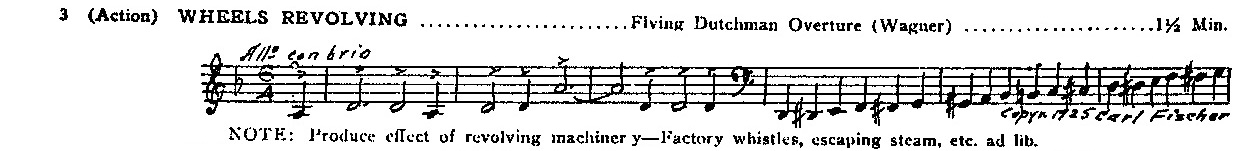

What is a musical cue sheet?

It was not uncommon for films to be tightly scheduled.

A film might finish its run at one theater, then be shipped to another theater and open the very next night.

That made it very difficult for a theater’s music department to prepare a score ahead of time.

So for most films, a cue sheet was sent ahead of the film.

It would contain a list of scenes in the film,

with a small sample of music suggested by the cue sheet compiler as appropriate for that scene.

The theater’s music director would compile a score,

perhaps using some of the suggestions (if the theater had them in its library),

and making substitutions of similar music for other scenes.

Cue sheets were not prepared by the movie producers,

but by people working for music publishing companies.

Often you can catch the cue sheet compiler pushing his own compositions,

or other pieces recently published by his publishing house.

|

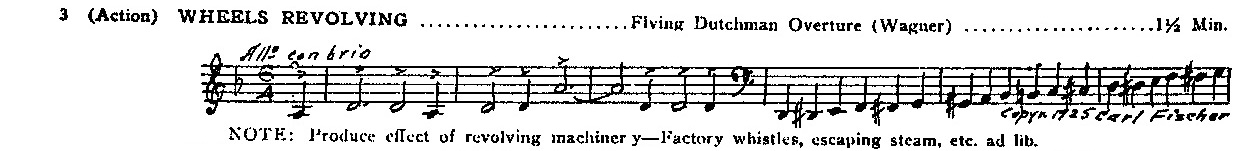

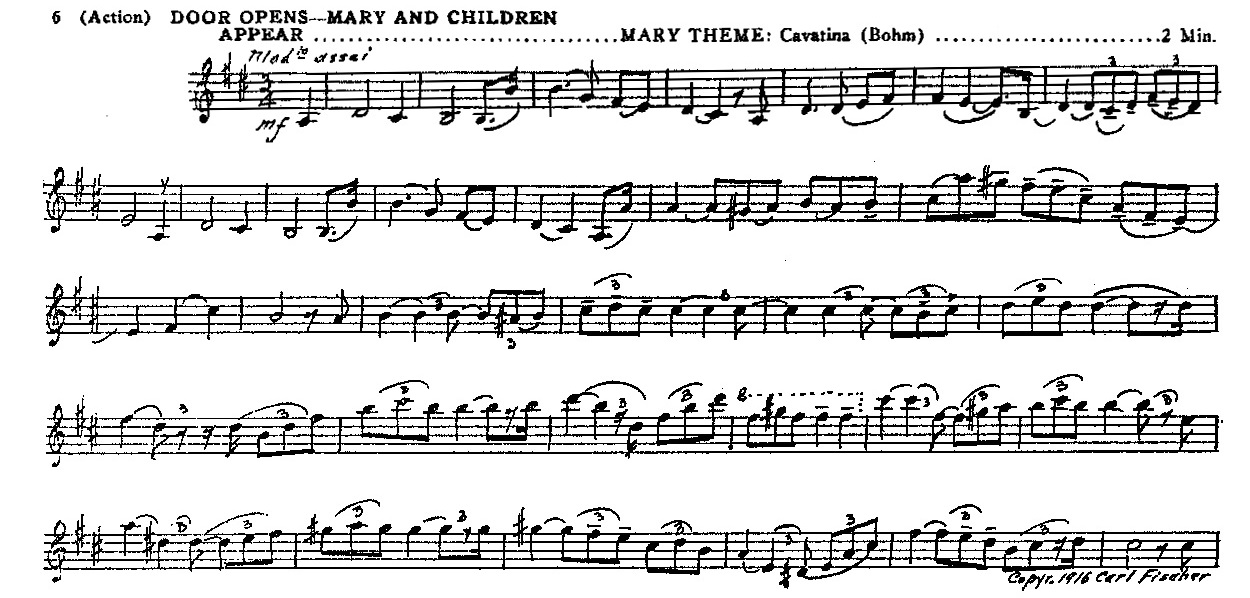

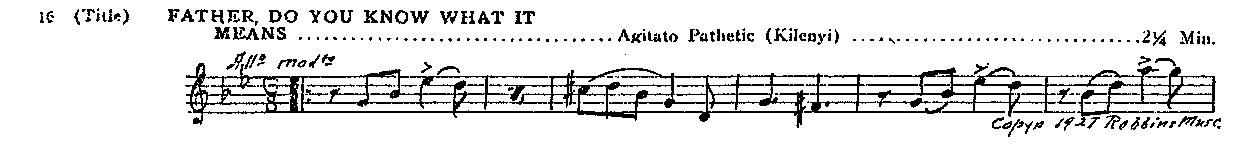

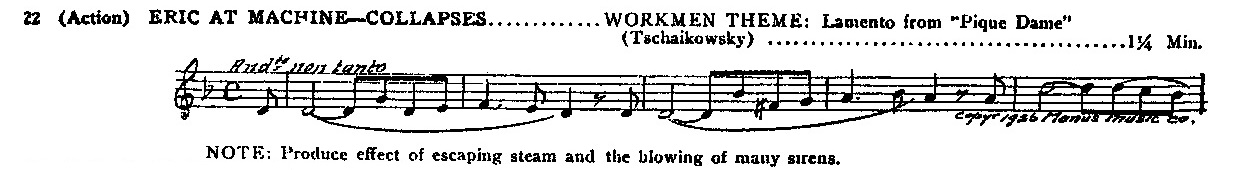

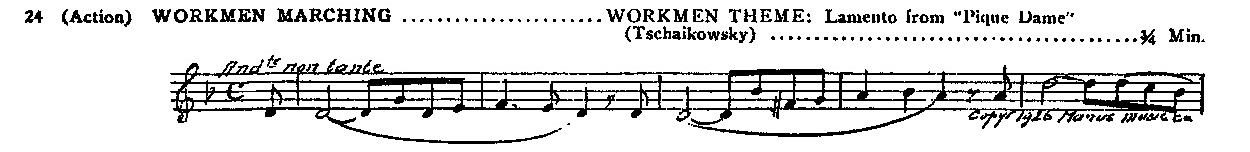

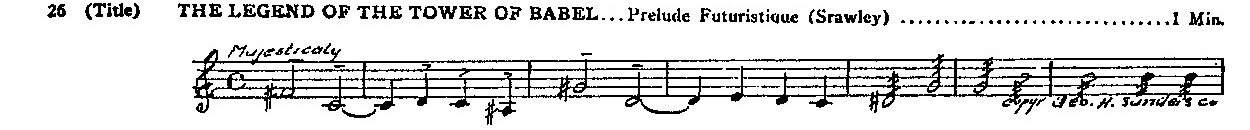

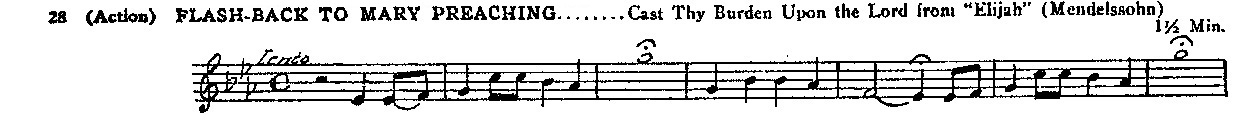

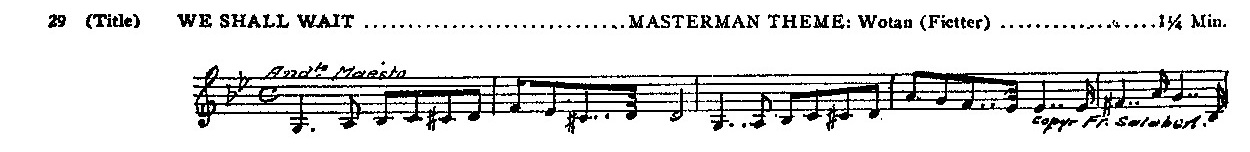

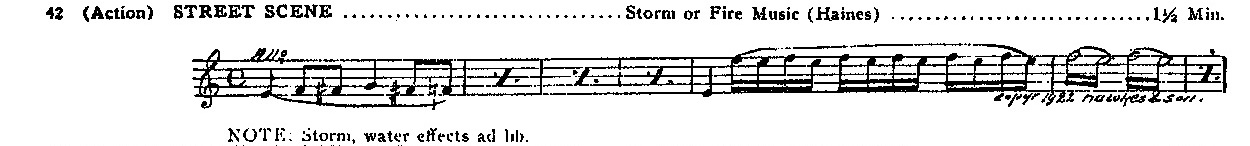

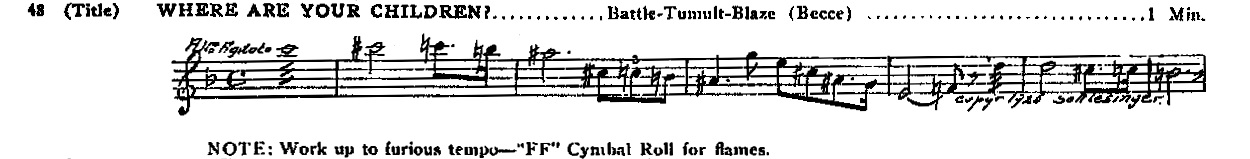

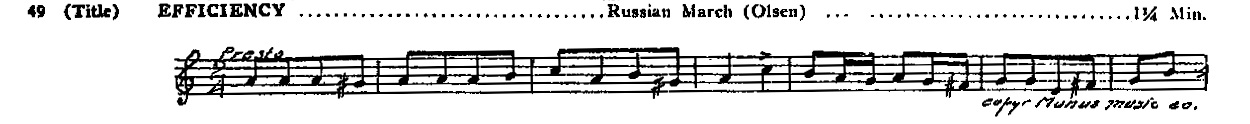

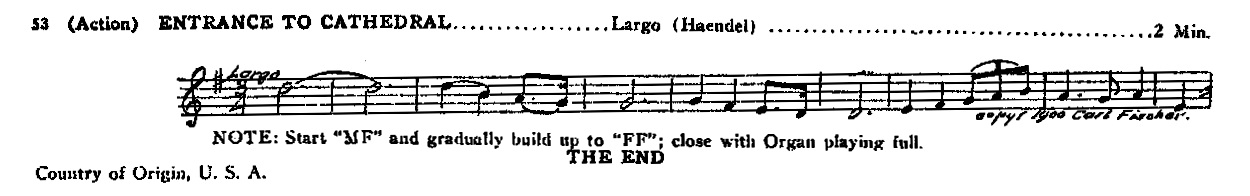

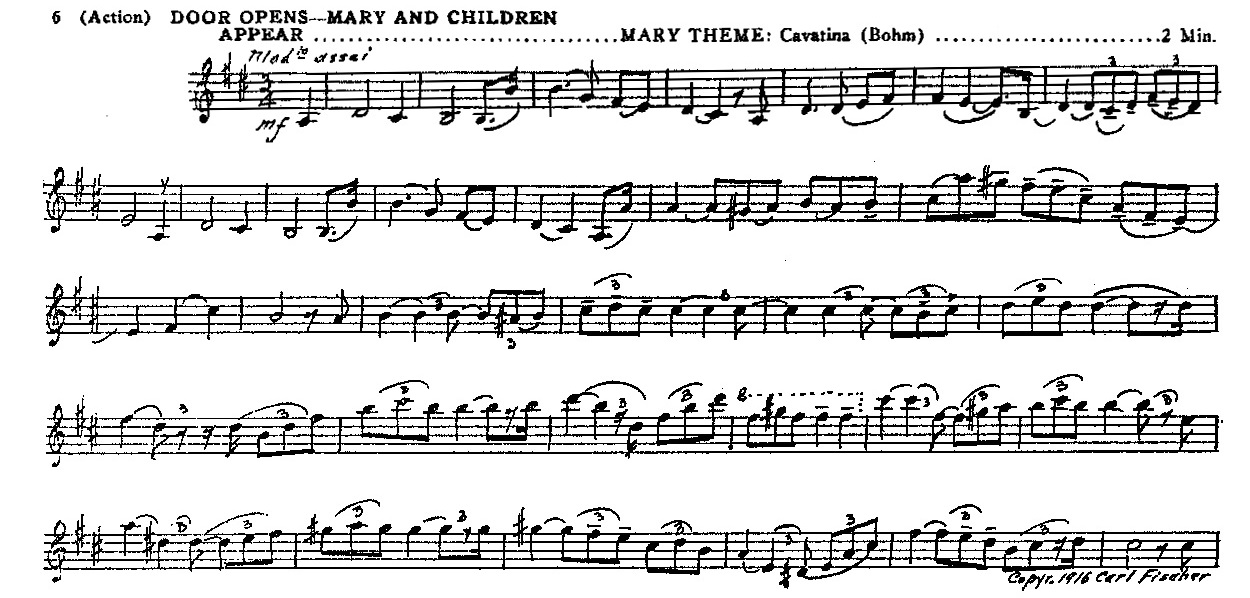

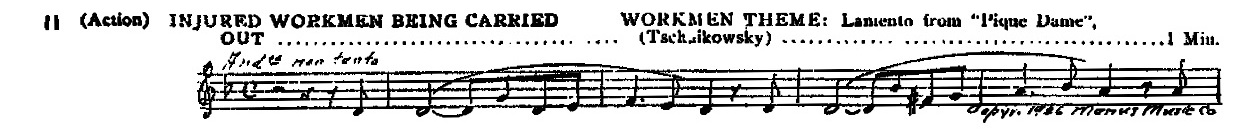

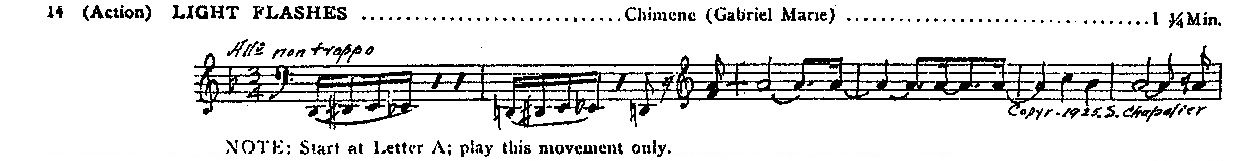

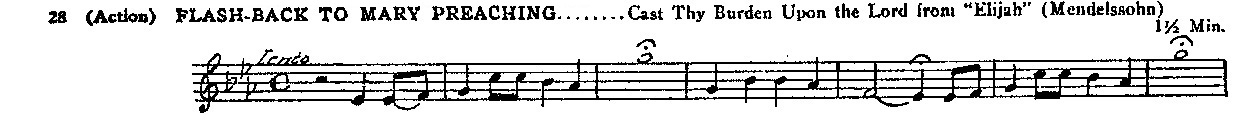

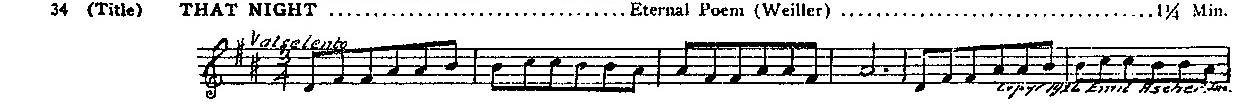

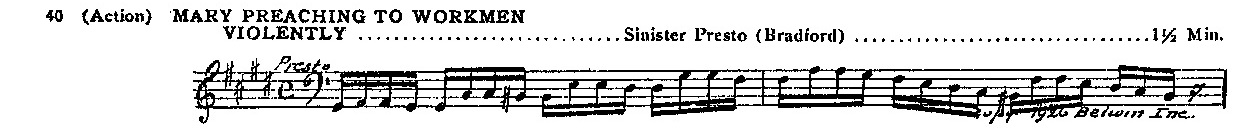

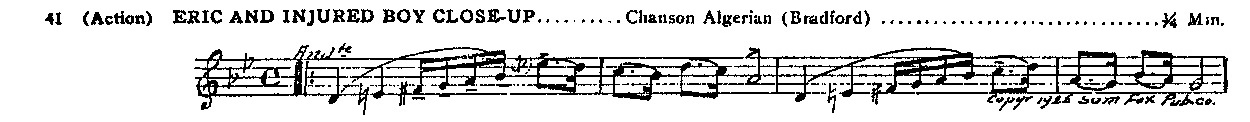

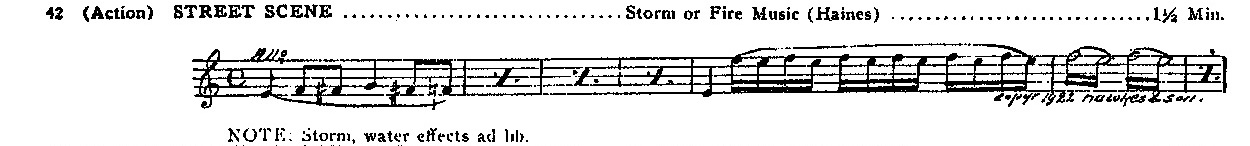

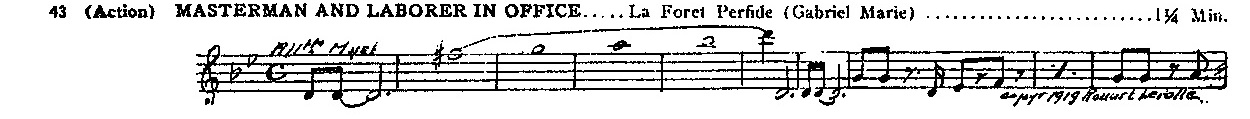

Here are Bradford’s cues, and I found some of these pieces loaded to YouTube and other websites.

So, here we go:

|

Isaac Snoek (1870–1943),

Ouverture dramatique (op. 135), pour orchestre, avec piano conducteur

Paris: J. Yves K., éditeur, 1926

Printed score available online

This was played over the credits added by Paramount.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

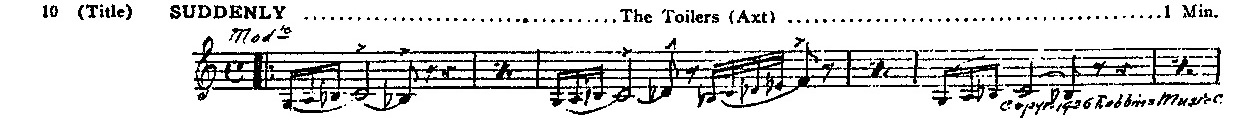

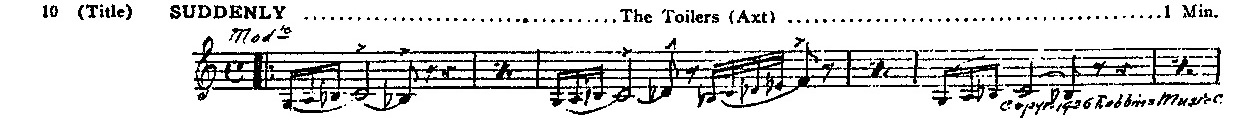

William Axt (1888–1959),

The Toilers

sheet music

I don’t know where the “Suddenly” title appeared.

It is not in the Harry Davidson print.

My guess is that it comes just before the explosion, or perhaps just before the transformation into Moloch.

|

|

|

|

|

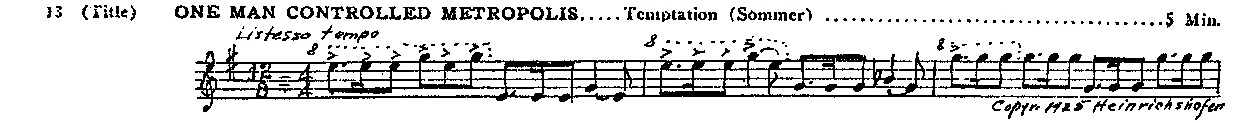

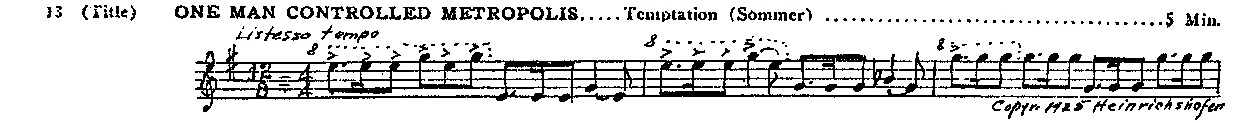

Hans Sommer (1904–2000), Temptation

Not available online

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

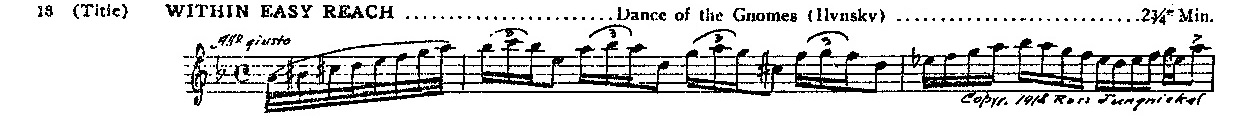

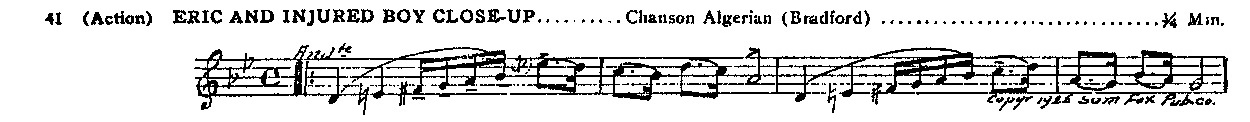

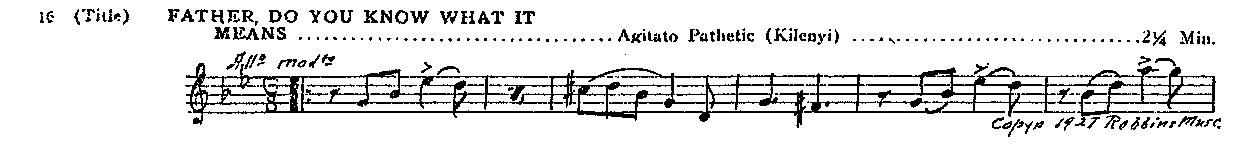

Alexander Ilyinsky (1859–1920),

Gnomes, 3rd movement of Noure et Anitra, opus 13

full score

“Within easy reach” is a title that does not appear in any print I have seen.

I suppose it introduced Rotwang’s house.

|

|

|

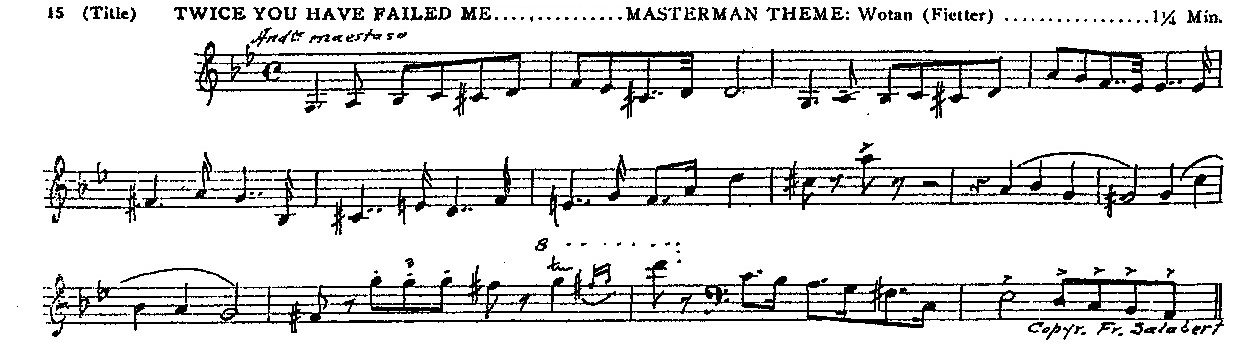

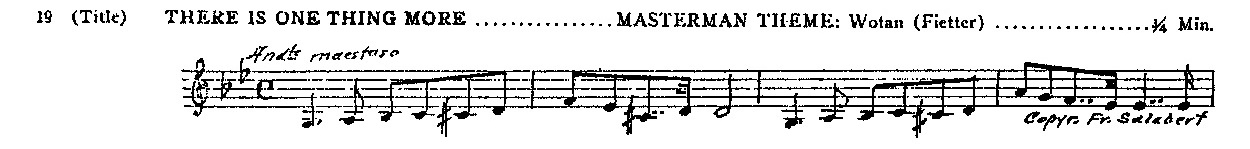

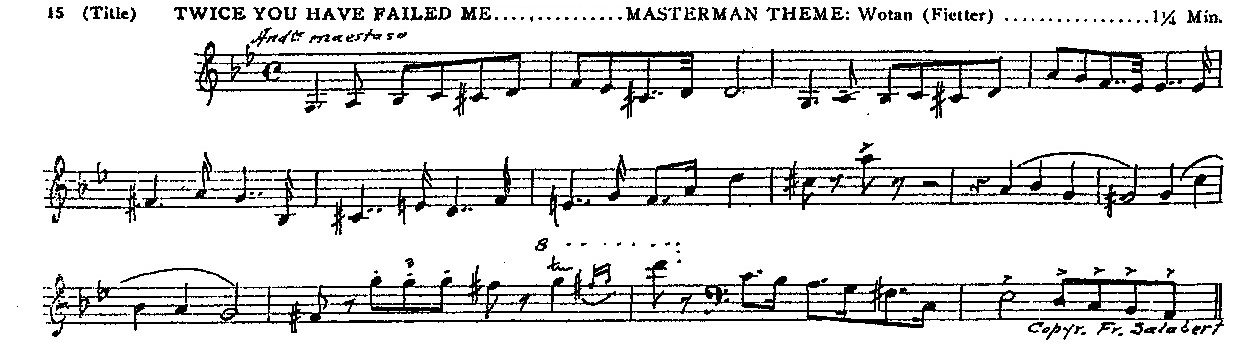

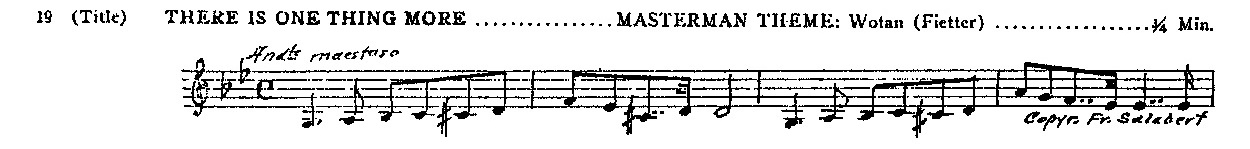

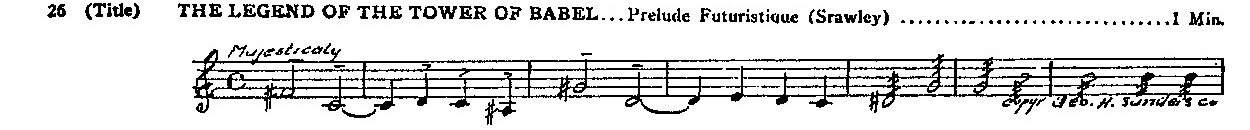

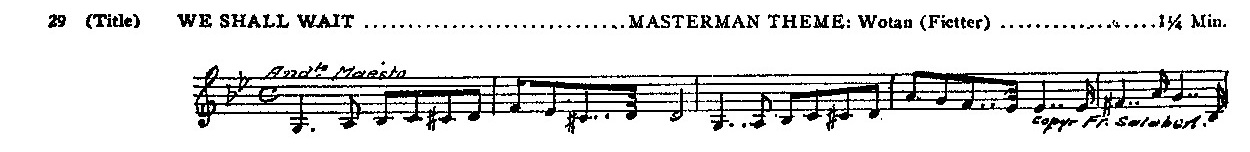

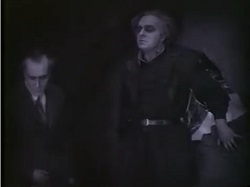

C. Fietter (1884–1946),

Wotan

Printed score available online

“There is one thing more” is a title that does not appear in any print I have seen.

I assume it belonged to this scene with Rotwang and Masterman.

|

|

|

Gaston Borch (1871–1926),

Enigma

“Flash-back” was used differently in the 1920’s; it meant “cut back to.”

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Louis Bourgeois (1510–1559),

Old Hundredth

This is an excellent example of how poorly proofread these cue sheets were,

how slipshod was their production.

Masterman and Rotwang do not disappear.

Masterman walks off, but Rotwang stays behind.

|

|

|

|

|

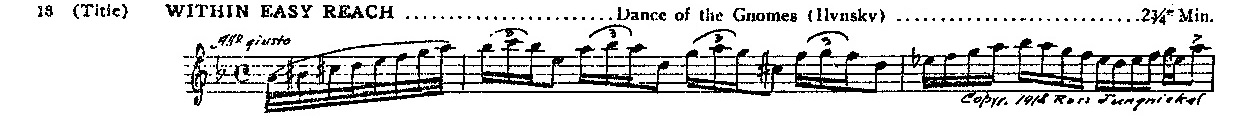

Alexander Ilyinsky (1859–1920),

Gnomes, 3rd movement of Noure et Anitra, opus 13

full score

“Rotwang lost no time” is a title I have not seen in any print.

|

|

|

|

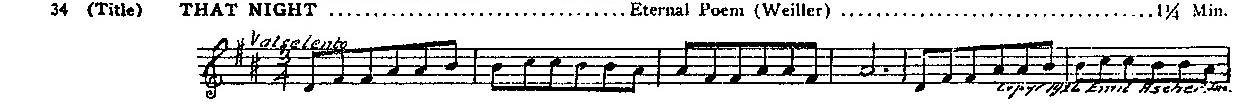

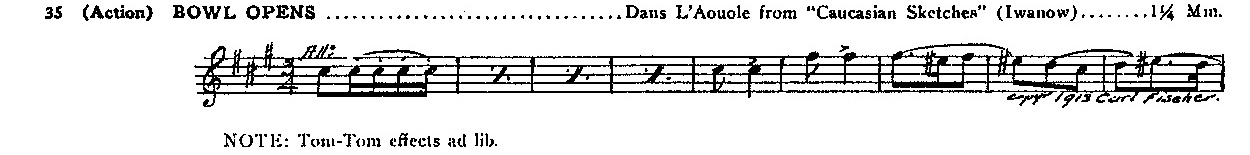

Mikhail Ippolitov-Ivanov (1859–1935),

In the Village,

Caucasian Sketches, Suite No. 1

It is now definitive that this scene was included in the première print shown at the Rialto in Manhattan in March 1927.

It would be deleted in early August, and it is omitted from the Harry Davidson print.

|

|

|

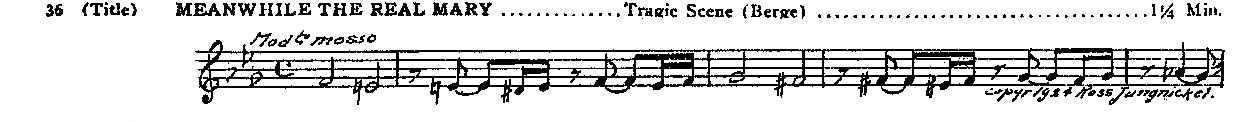

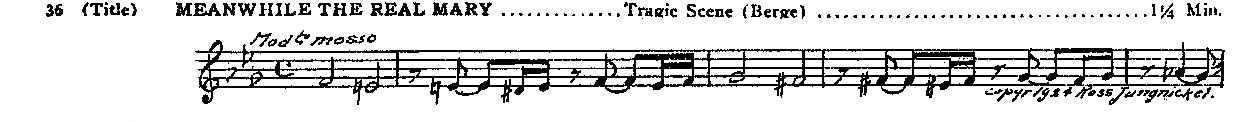

Irénée Bergé (1867–1926),

Tragic Scene

Printed score available online

In the Australian release, the order of the scenes was 38, 36, 37.

|

|

|

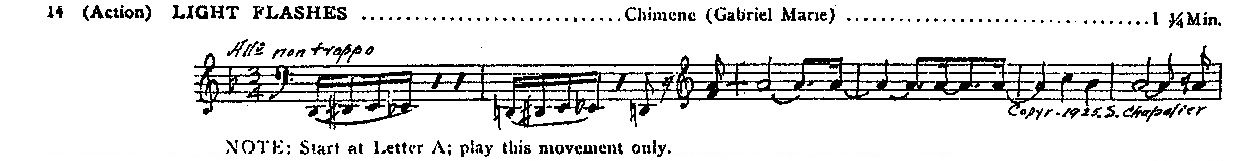

Jean Gabriel-Marie (1852–1928),

Le Seigneur de Kermor

Someone who called him/herself silentmoviefan used this piece in some scenes from The Eagle.

I do not recalled ever having seen the title, “But Rotwang did not reckon.”

In the Australian release, the order of the scenes was 38, 36, 37.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

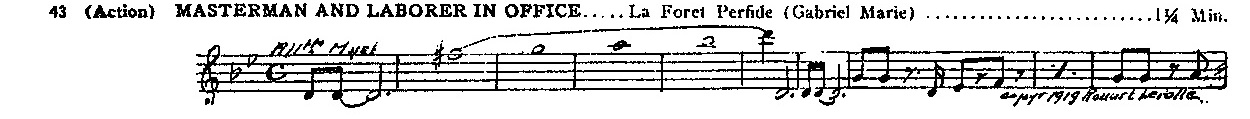

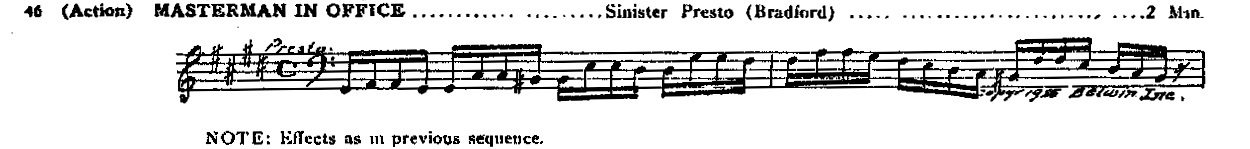

Jean Gabriel-Marie (1852–1928),

La foret perfide

Not available online

This is another example of careless proofreading.

Masterman is alone in the office. The laborer is on view only through a videophone.

|

|

|

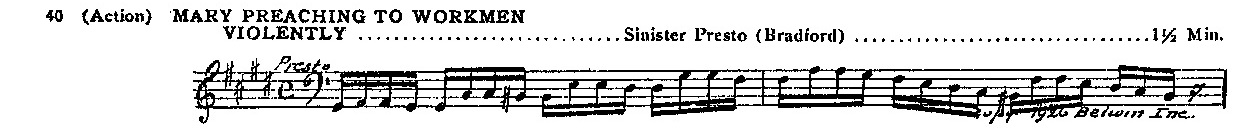

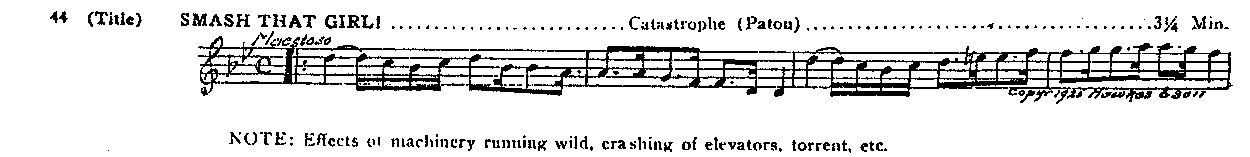

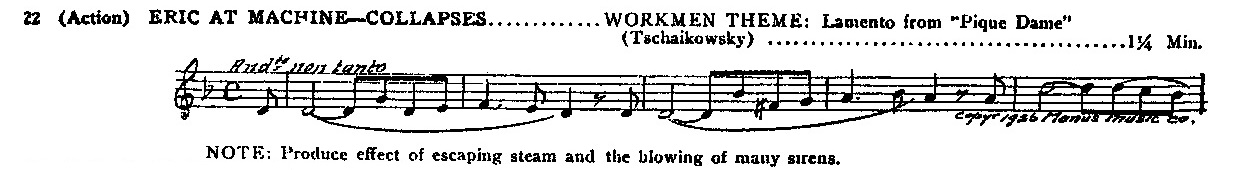

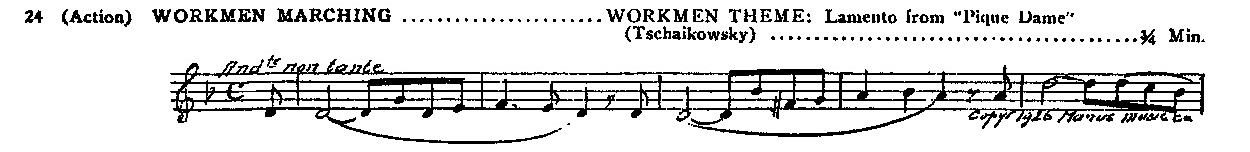

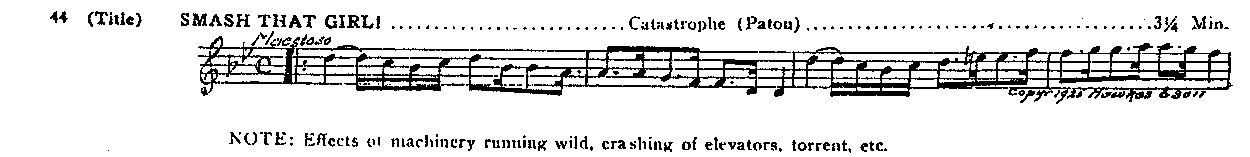

Édouard Patou,

Catastrophe

In the Paramount edition, the title was indeed “Smash that girl!”

In the export edition, the title was “Do what you can to hold them. Reason with them. Capture that girl!”

(Enno Patalas, Metropolis in/aus Trümmern, Berlin: Dieter Bertz Verlag: 2001, p. 136)

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

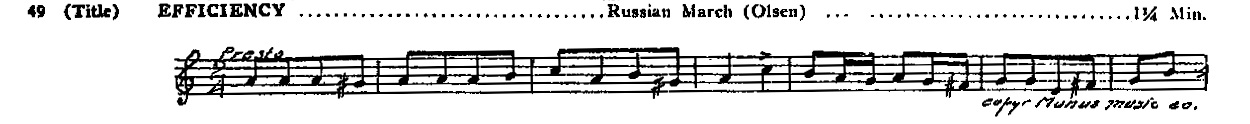

Olsen (Ольсенъ),

Russian March (Русскiй Маршъ)

No clue who this Olsen person was, no clue at all.

Oh. Wait. Found him! Not Olsen, but Ohlsen.

Emil Ohlsen,

27 May 1860 – 1943.

The title, “Efficiency,” does not appear in any print of the film I have seen.

This is the only spot where it could possibly fit, though it obviously does not belong.

Yup, I was right.

Enno Patalas, in Metropolis in/aus Trümmern, p. 155, states that in the American edition

there was a title here: “Efficiency triumphant !”

|

|

|

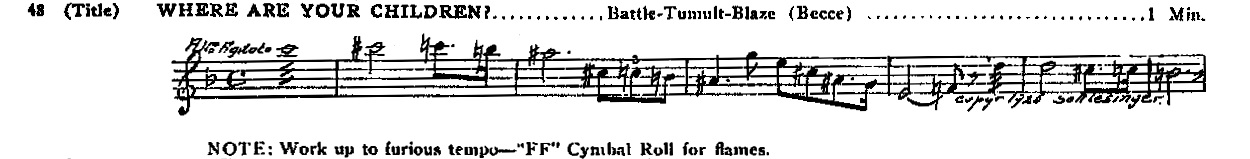

Édouard Patou,

The Ambush

This scene was trimmed slightly in early August 1927 to reduce the images of the witch being burned at the stake.

The trimming was done for the Australian release as well.

|

|

|

John Stepan Zamecnik (1872–1953),

Fury

Printed score available online

|

|

|

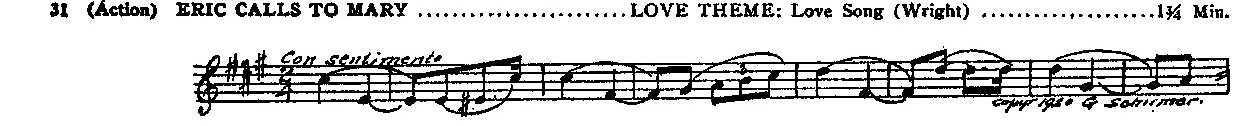

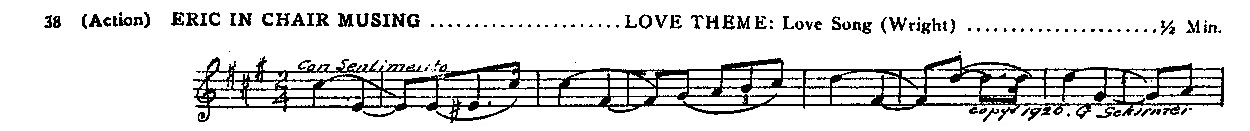

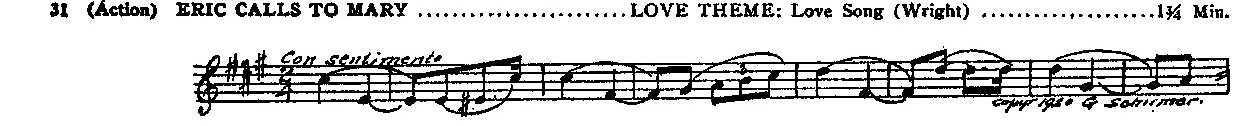

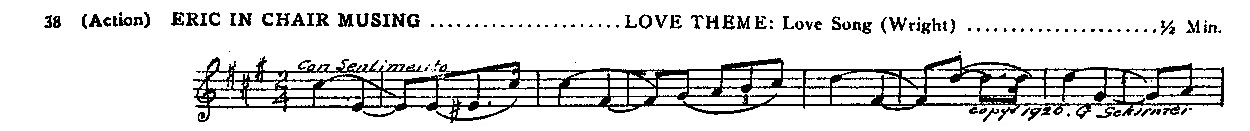

Minnie T. Wright (1874–1929),

Love-Song

“I thank Thee dear God” does not appear in the Harry Davidson print,

though “Thank heaven!” appears in the Eckart Jahnke edition of 1972.

The latest restoration does not have, and does not need, any title here.

|

|

|

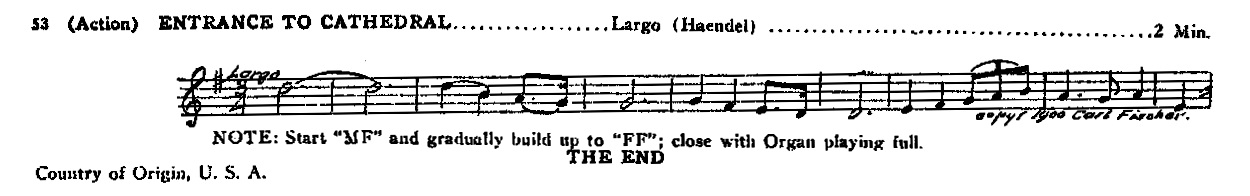

George Frideric Handel (1685–1759),

Largo

|

|

As far as I know, the US Paramount edition of Metropolis was never issued on home video,

and so the closest approximation we can find to it is the Australian print once held by Harry Davidson.

It was from the export negative rather than the US negative, but it is still useful as a reference,

and most of the frame grabs above are thus from the online Harry Davidson print.

What do we learn from the above cues?

We learn that this is a game that cannot fail.

These cues, used in countless cue sheets for countless movies, became clichéd by repetition.

They followed a predictable formula.

For a suspense scene, the compiler would grab one of a few dozen appropriate suspense pieces.

For a love scene, the compiler would grab one of a few other dozen appropriate love pieces.

And so on and so on and so on.

It was music score created by assembly line. Entirely impersonal.

Yet it could not go wrong, because most of the music was wonderful, so good that it would work automatically.

|

As soon as the Paramount executives watched the film in December 1926, they hired playwright

Channing Pollock

to mop up the mess for a March 1927 release.

Why?

One reason, certainly, was to reduce the film’s impact.

On top of that, there was the usual reason, probably.

The same reason that censors chop things away,

the same reason the

As soon as the Paramount executives watched the film in December 1926, they hired playwright

Channing Pollock

to mop up the mess for a March 1927 release.

Why?

One reason, certainly, was to reduce the film’s impact.

On top of that, there was the usual reason, probably.

The same reason that censors chop things away,

the same reason the