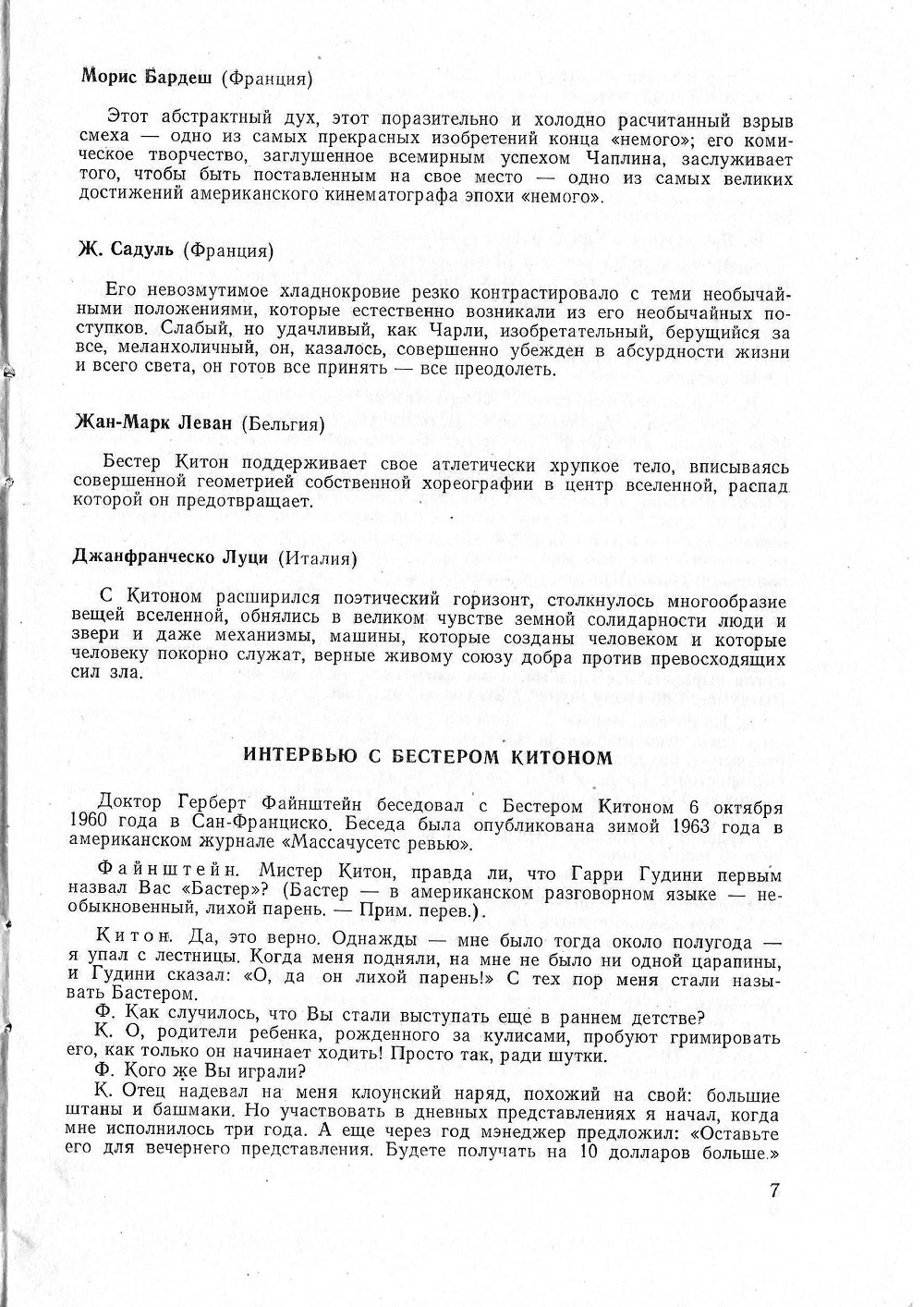

Бестер Китон в СССР

(aka Бастер Китон,

Бэстер Китон,

Бестер Кейтон,

Бестер Кэйтон)

|

|

|

CALLING ALL RUSSIANS!

Are any of you in Russia or in other parts of what was once the Soviet Union?

Would you enjoy doing some research?

|

|

I asked a Russian colleague at https://busterkeaton.ru

for any information on the Buster silents that were shown in the Soviet Union in the 1920’s.

I was not expecting much and, to my delight, I received considerably more than I had anticipated.

With her permission, I reproduce all her goodies here.

|

|

Actually, my new Russian colleague did more than that.

I am browsing her website (courtesy of automatic translation)

and discover that she published a page on exactly the same topic,

with pretty much exactly the same sources!

And, actually, she did a better job than I did below.

Take a look:

https://busterkeaton.ru/027-keaton-in-ussr.

|

|

As I feared, research in the countries formerly under the Soviet Union is not easy.

As my colleague explained,

“After the end of the civil war in 1922,

the state of both the movie business and the legal field here left much to be desired.

This also makes it difficult to study data on screenings,

besides the fact that a centralized newspaper archive for the USSR similar to newspapers.com simply does not exist.

We may be able to trace individual cinemas in the capital and some shows in those provinces

for which we can find newspapers (though it will take a lot of time),

but the task of creating a relatively complete picture of distribution in the USSR

seems to me almost impossible at the moment.”

|

|

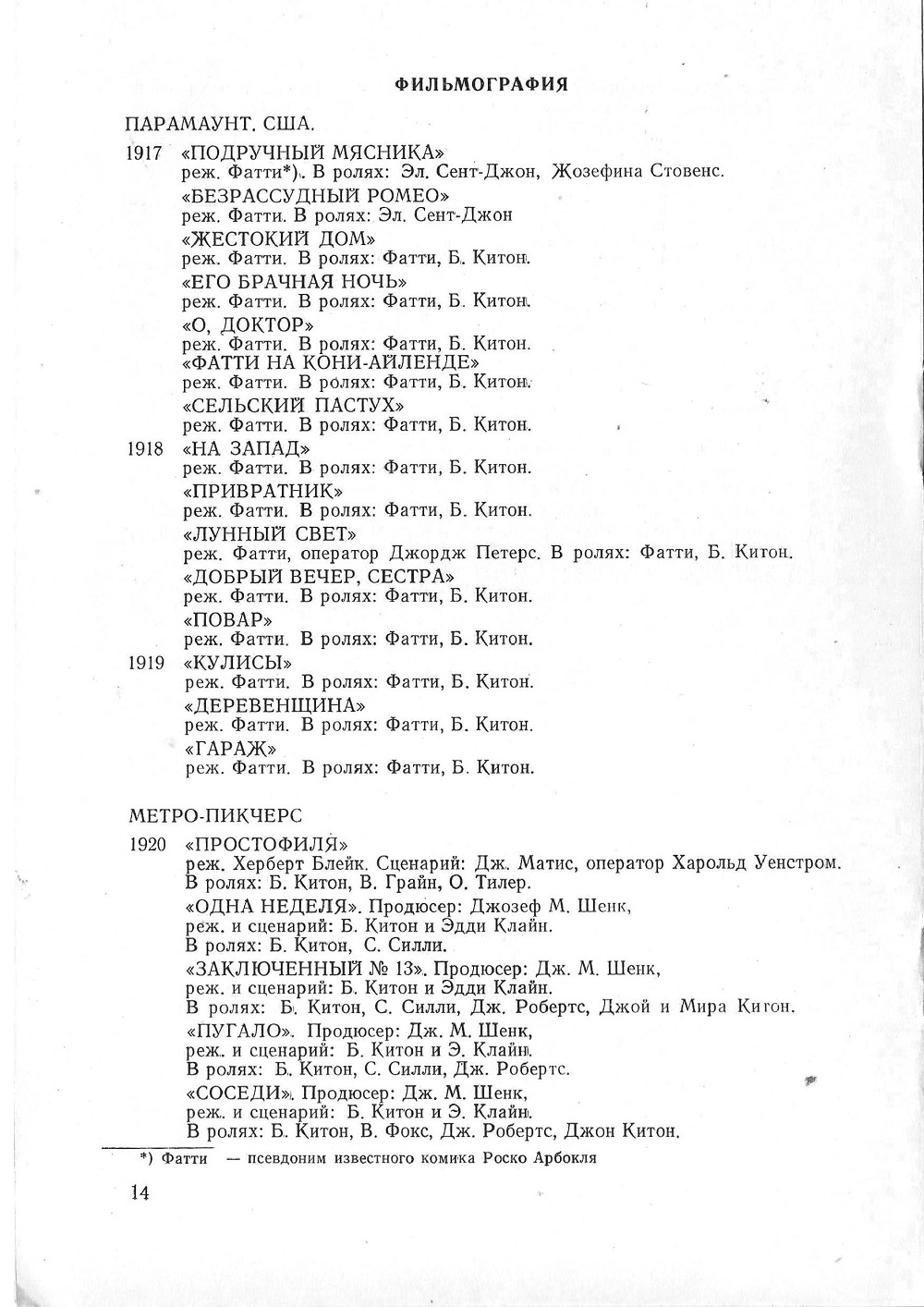

Despite that problem, some Buster researchers in Russia have done some marvelous work, and here it is!

As far as we know, several of Buster’s short films were issued in the Soviet Union sometime after 1920.

We know for certain that

The Bell Boy,

Out West

(На Диком Западе, a strange composite),

Convict 13

(Заключенный №13), and

The Haunted House (Призраки)

were released, but if any others were seen by Soviet audiences, well, that is the mystery.

|

|

As you know, Convict 13 is missing the ending.

Any time you watch it at the cinema or on any video, the ending is missing.

It just abruptly cuts off as Sybil and Buster walk away from the golf course.

Well now, thanks to my Russian colleague, I took a look at Заключенный №13,

and it has a little more of the ending!!!!!

It’s still not complete, but there’s an extra moment at the end.

So tantalizing!

Take a look:

|

|

mukuk2005, Заключенный №13 (1920) Бастер Китон / Convict 13 (Russian archive print), posted Apr 24, 2012. If YouTube disappears this, download it.

Unlike the editions available elsewhere, the first half is not from a 16mm bootleg, but from a rather good 35mm duplicate.

Also, there’s a little more at the end, though, sadly, it cuts off abruptly,

before the topper.

Buster always closed with a topper.

|

|

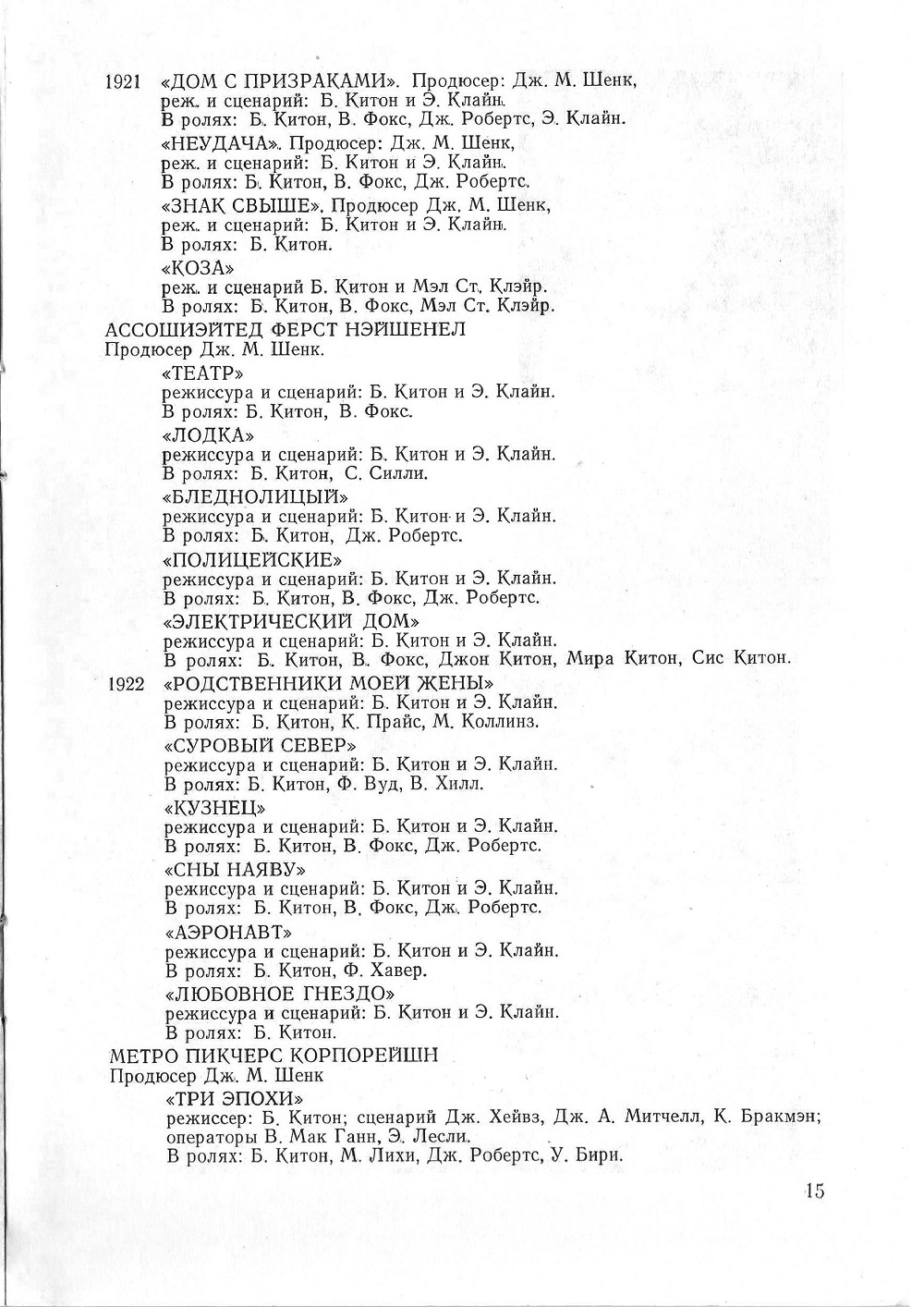

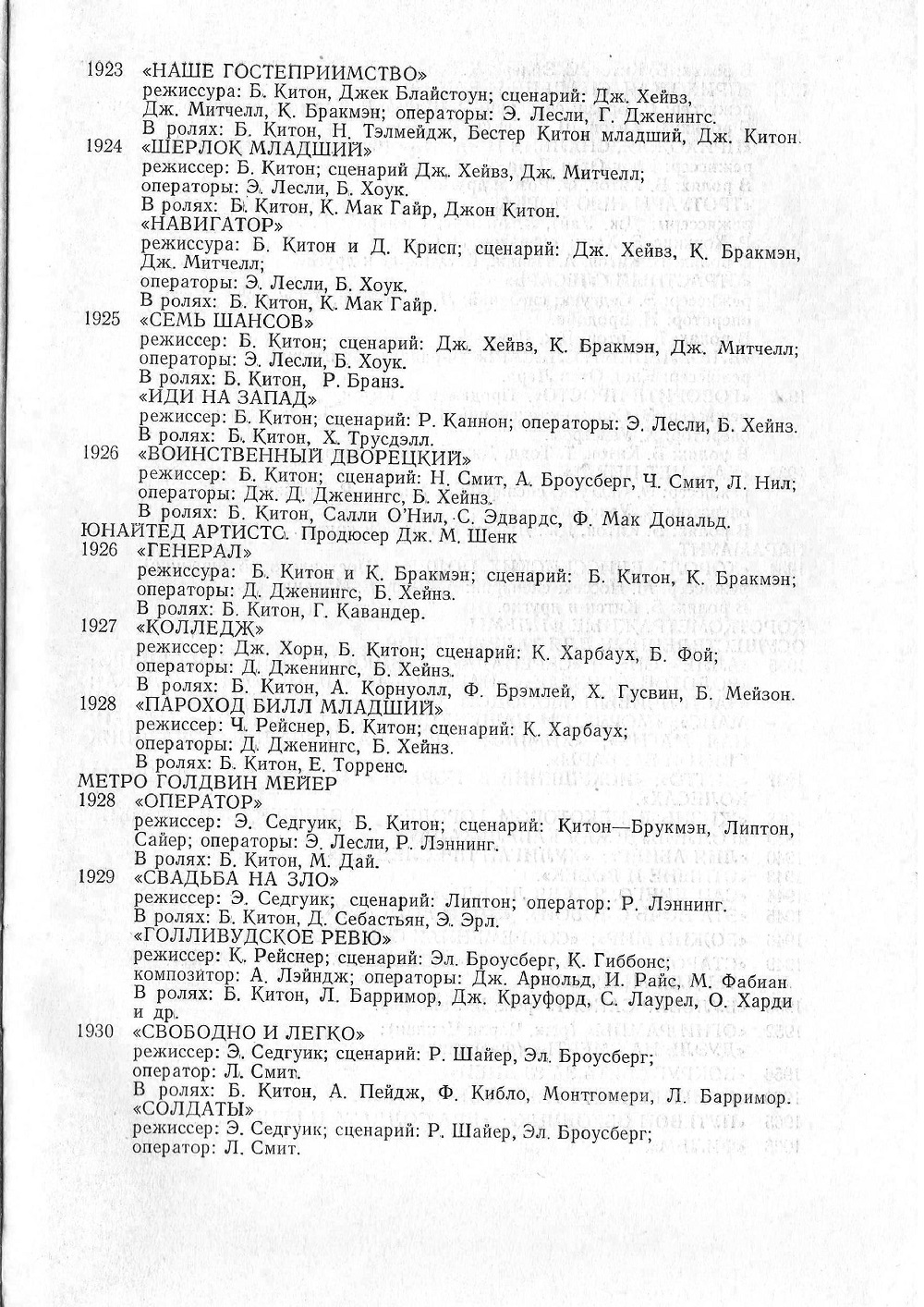

Only four of Buster’s silent features were released in the Soviet Union,

and all were distributed by Sovkino.

|

|

Одержимый

(Sherlock Jr.)

Released on 1 September 1925?????

Somebody on a production crew must have remembered this movie from almost 50 years before.

Or perhaps somebody on a production crew traveled to the US and caught the 1975 reissue.

You see, a momentary glimpse of Sherlock Jr. was included in

Здравствуйте, я ваша тётя!

(Hello, I Am Your Aunt!).

My colleague has set me right.

Clown school and cinema school taught Buster’s movies,

and so filmmakers were all familiar with Sherlock Jr.

I wonder which prints were used at those schools, and what their sources were.

|

|

The Russian Busterphiles sent me a little more:

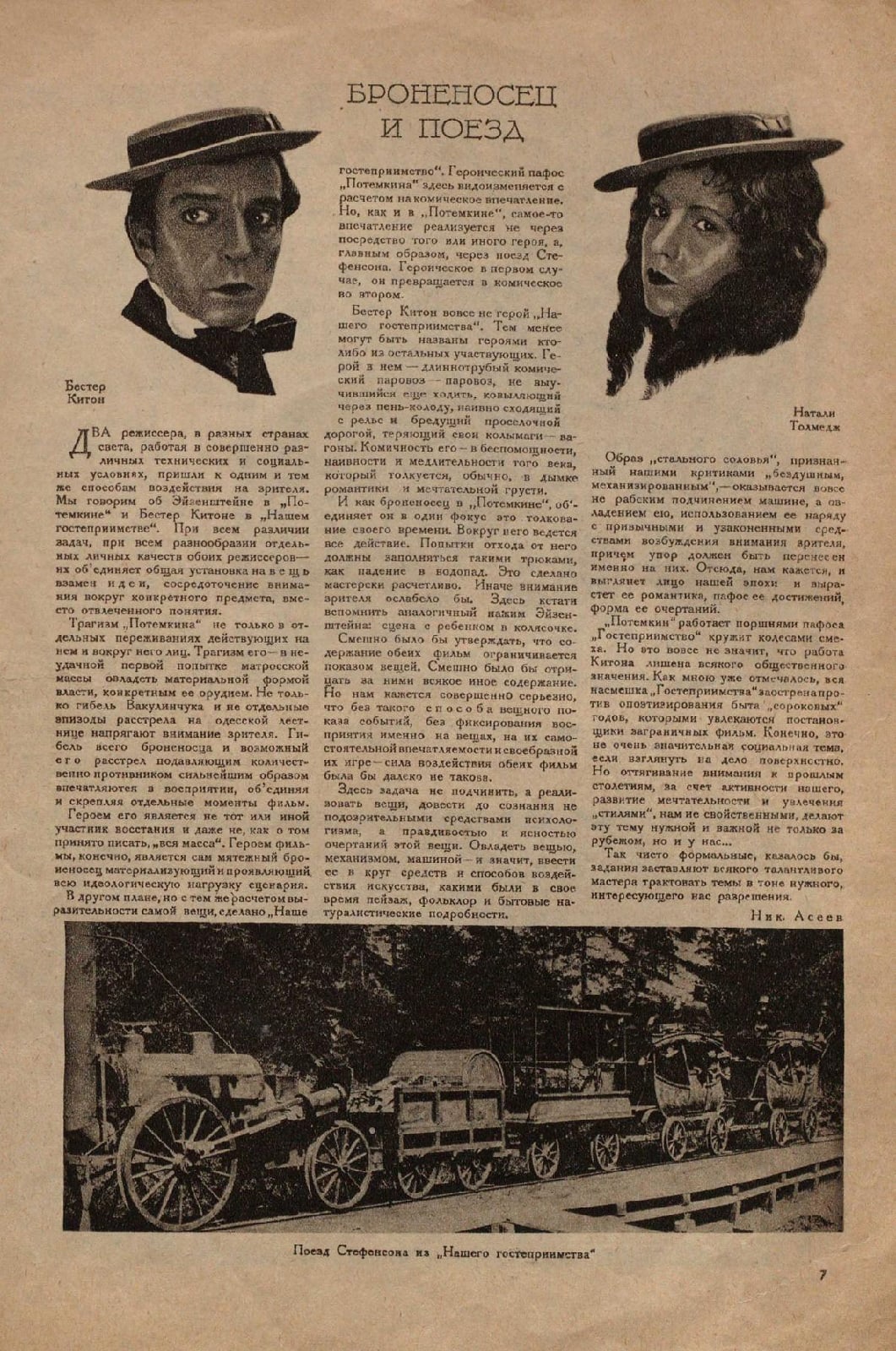

|

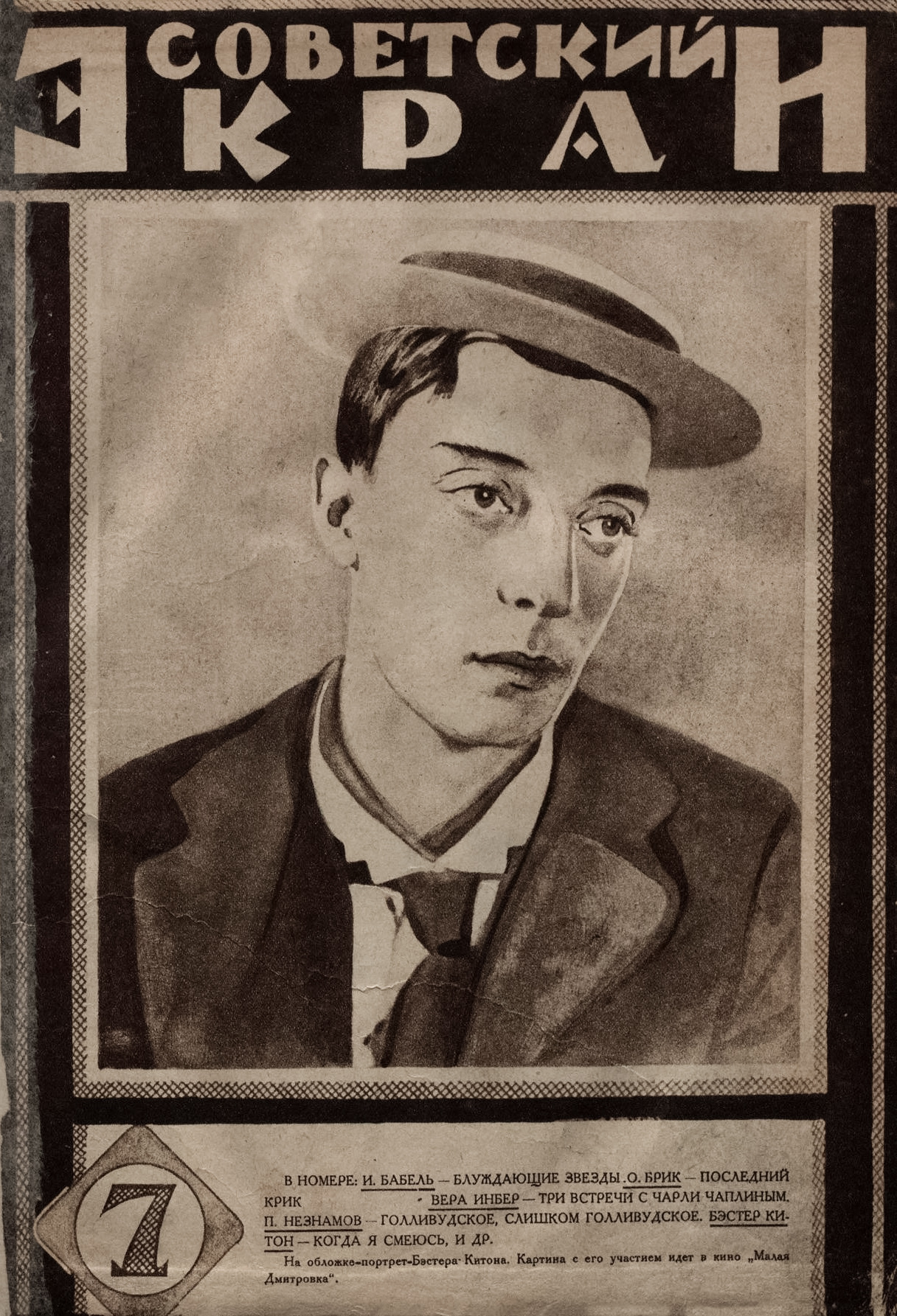

Советский экран (Soviet Screen) № 36 .jpg) Кино, еженедельная газета (Kino Weekly Newspaper), 3-й год издания (3rd year of publication), 29 сентября 1925 г. (29 September 1925), № 28 (108) |

|

The above ads I found online.

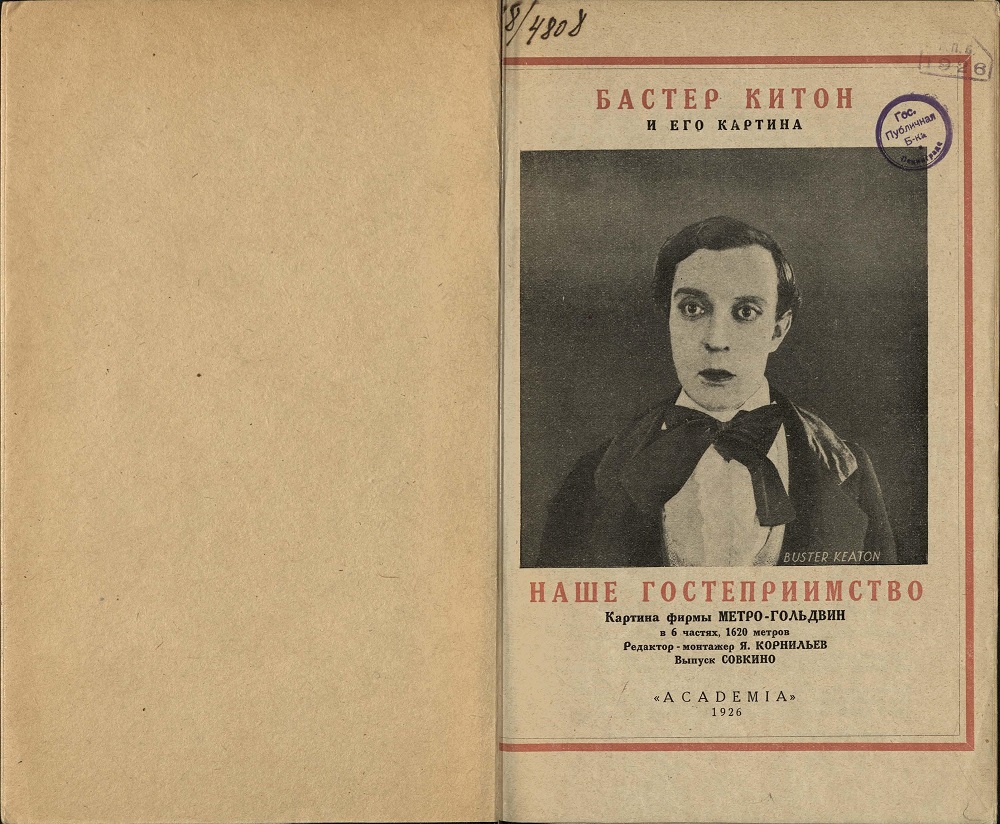

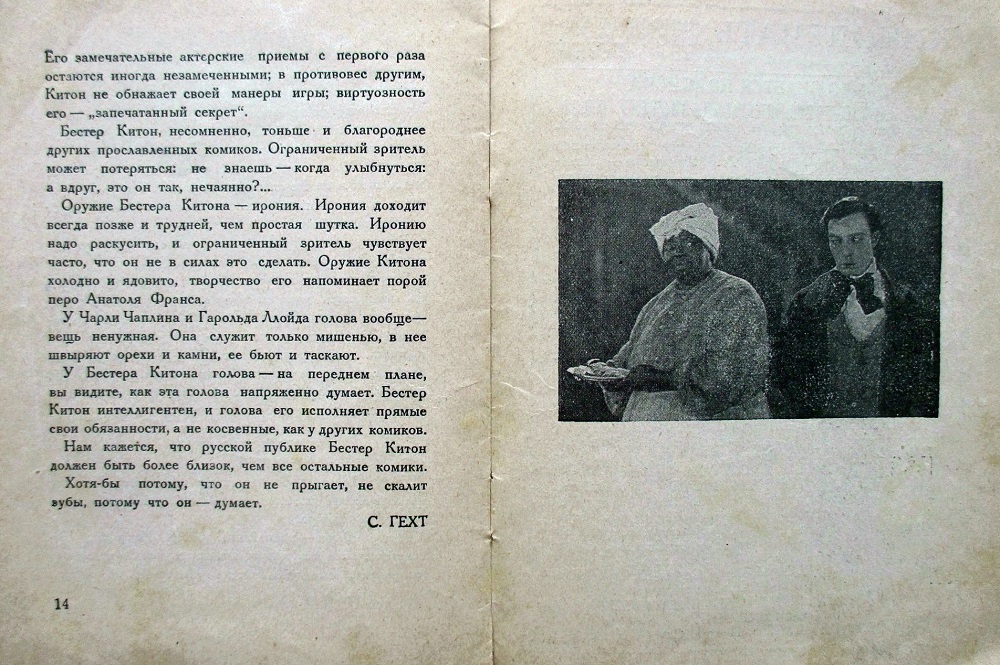

Then https://busterkeaton.ru sent me the following brochure,

which I suppose was handed out or perhaps sold at showings of Our Hospitality.

|

|

|

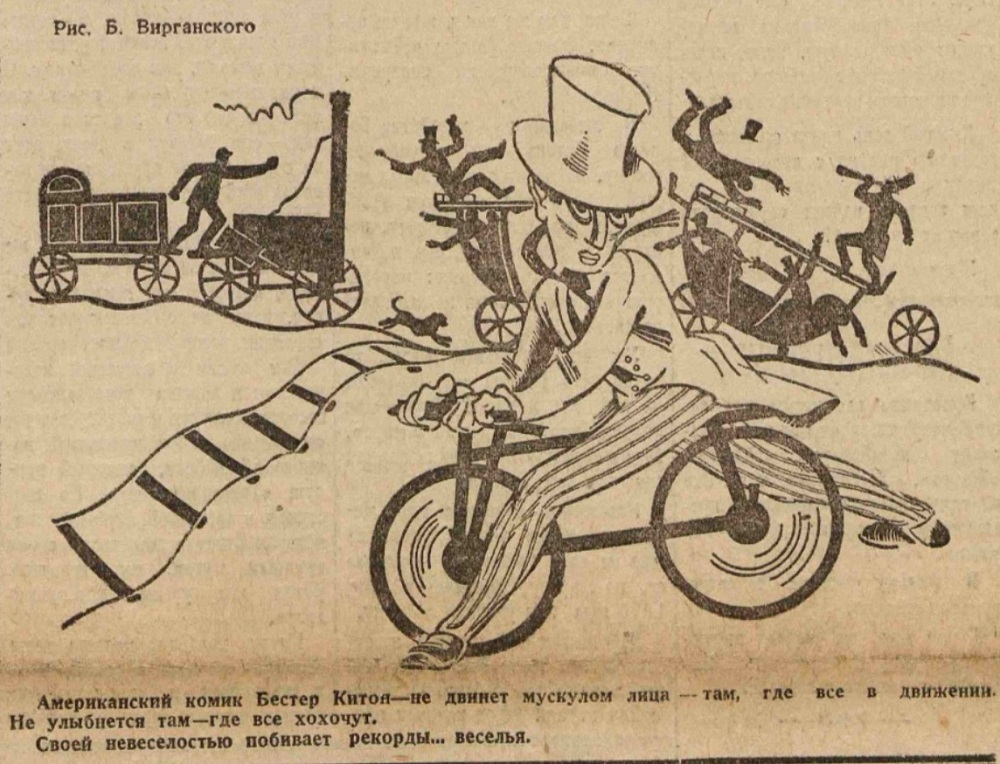

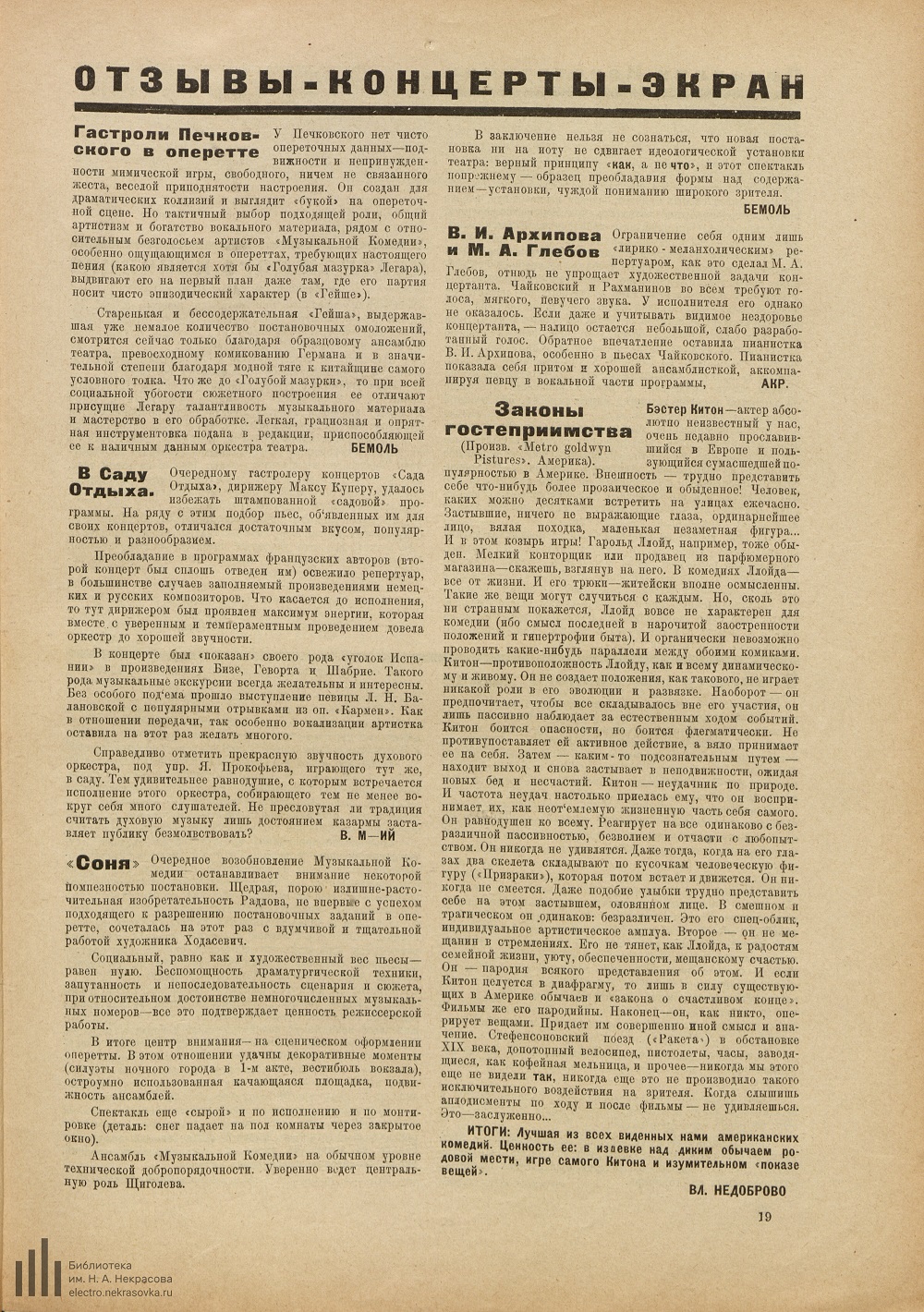

And another:

|

|

|

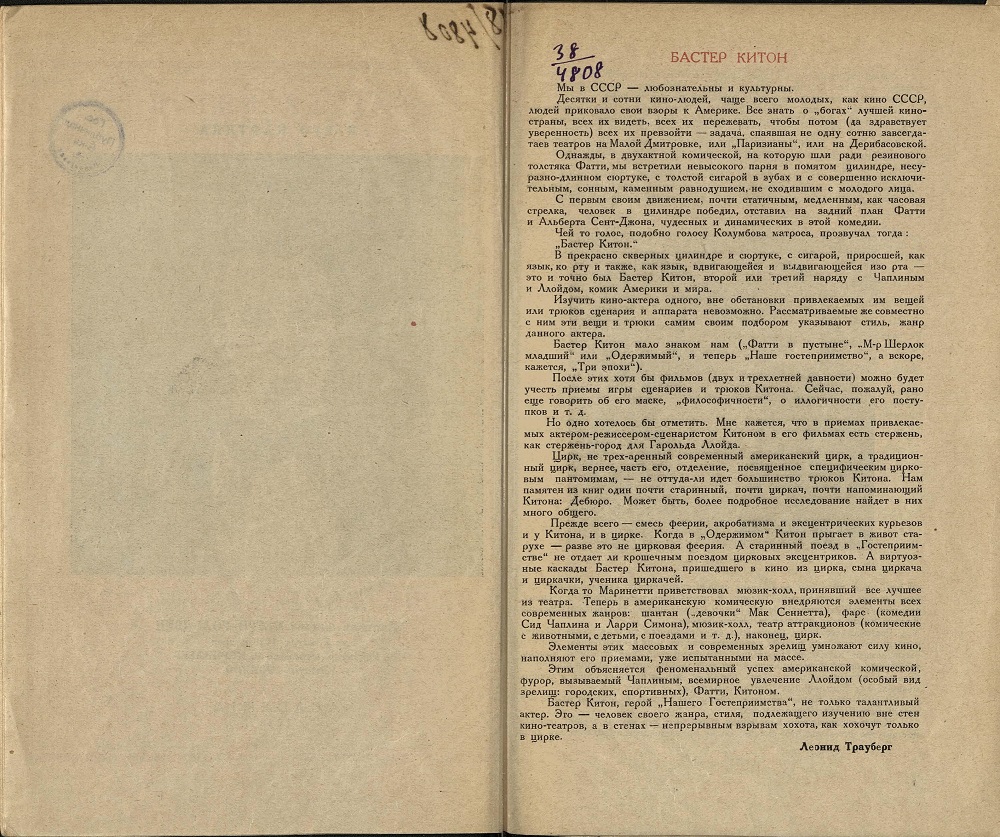

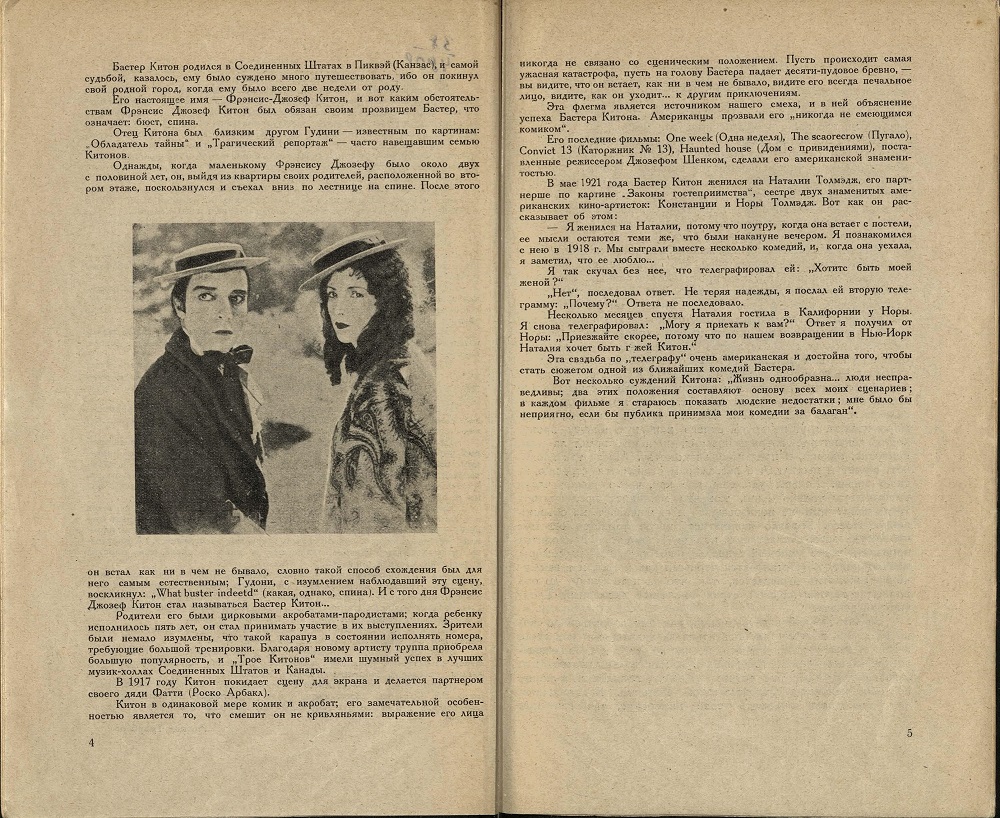

I’ll get a translation of the above later on.

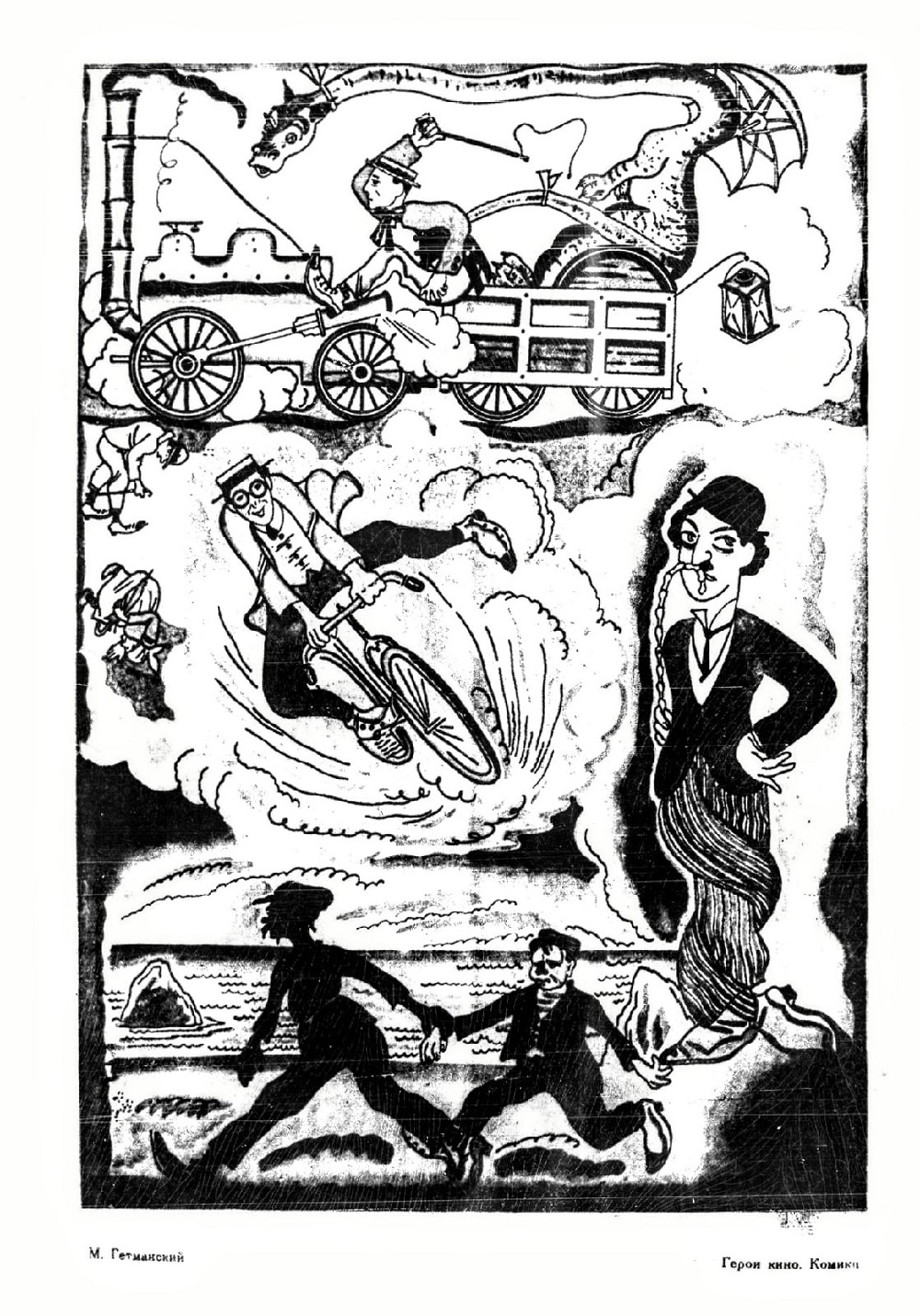

In the meantime, here’s more that they sent over:

|

Source unknown  Жизнь искусства (The Life of Art), (№28) 13 July 1926 _1926-02-09.jpg) Кино, еженедельная газета (Kino Weekly Newspaper), № 6 (126), 9 февраля 1926 (9 February 1926)  Советский экран (Soviet Screen) _1926-03-02.jpg) Кино, еженедельная газета (Kino, Weekly Newspaper) № 9 (129), 2 марта 1926 (1 March 1926)  Советский экран (Soviet Screen) |

|

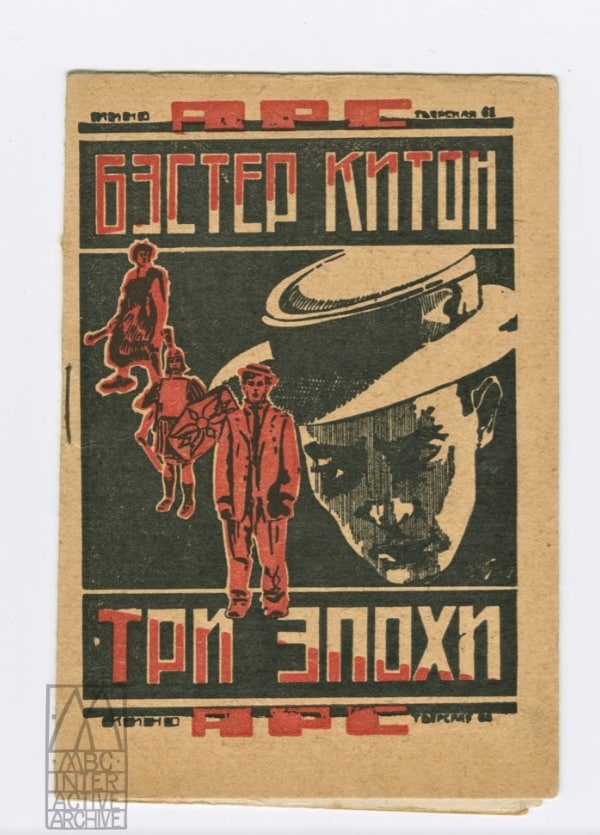

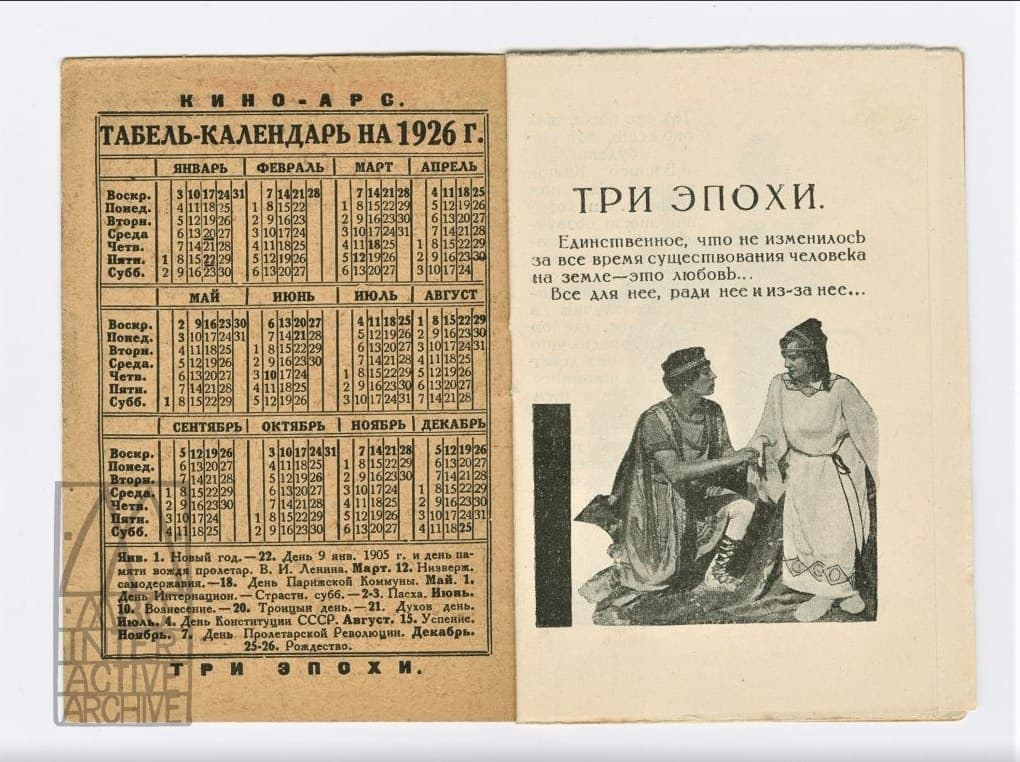

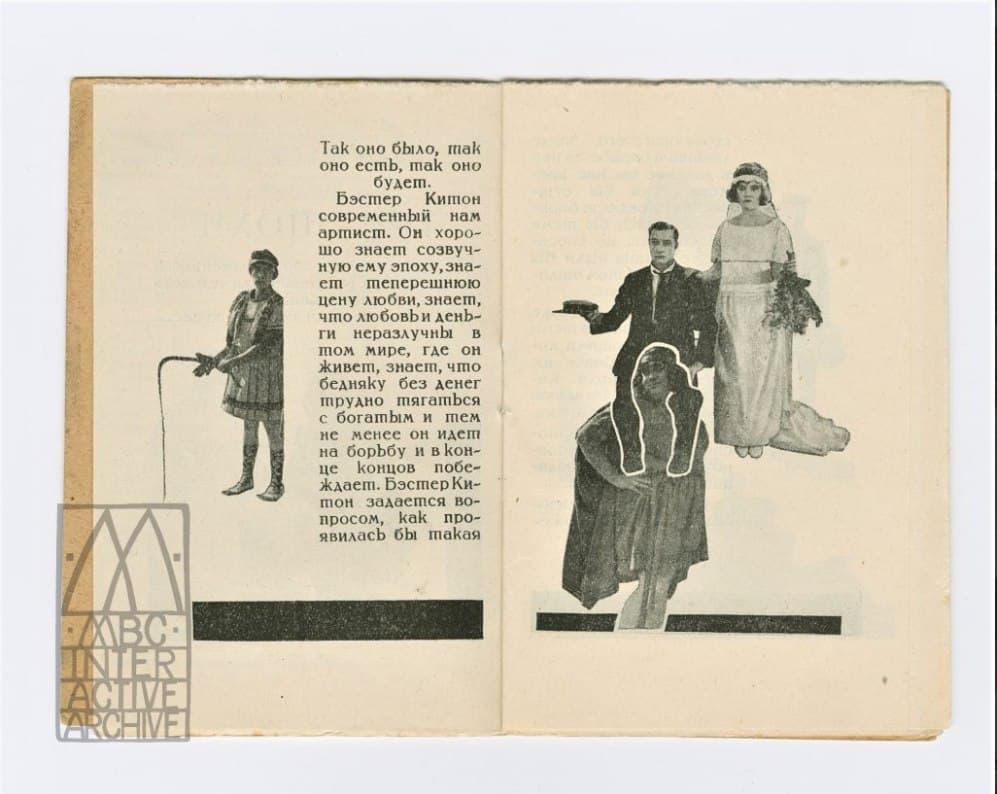

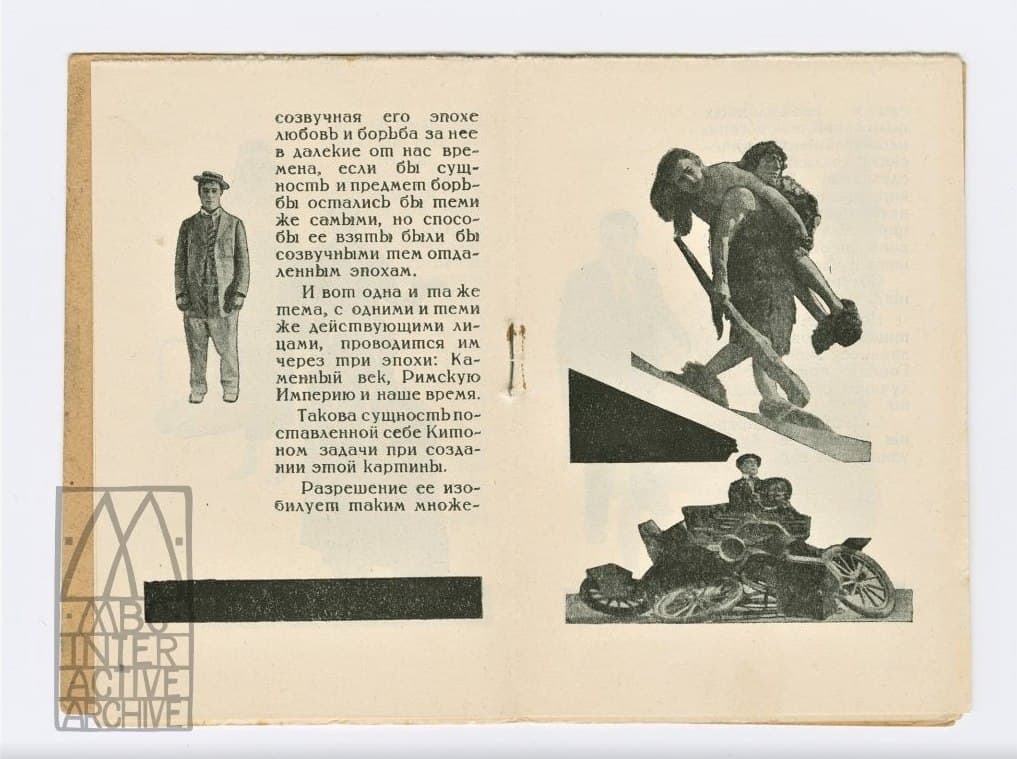

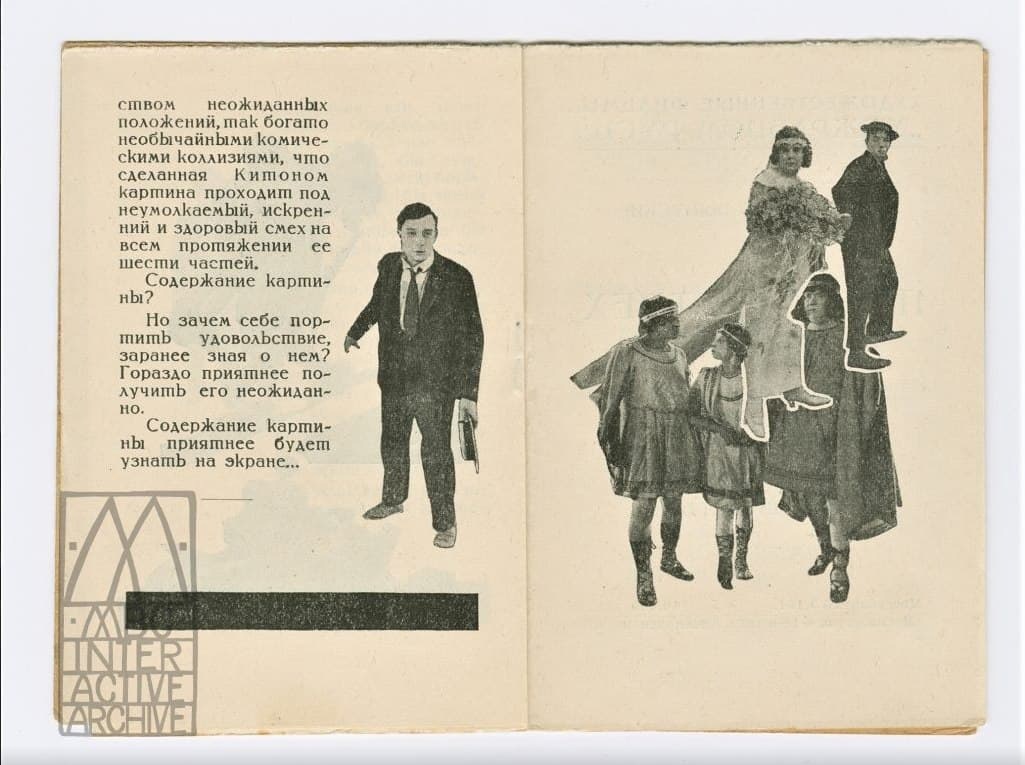

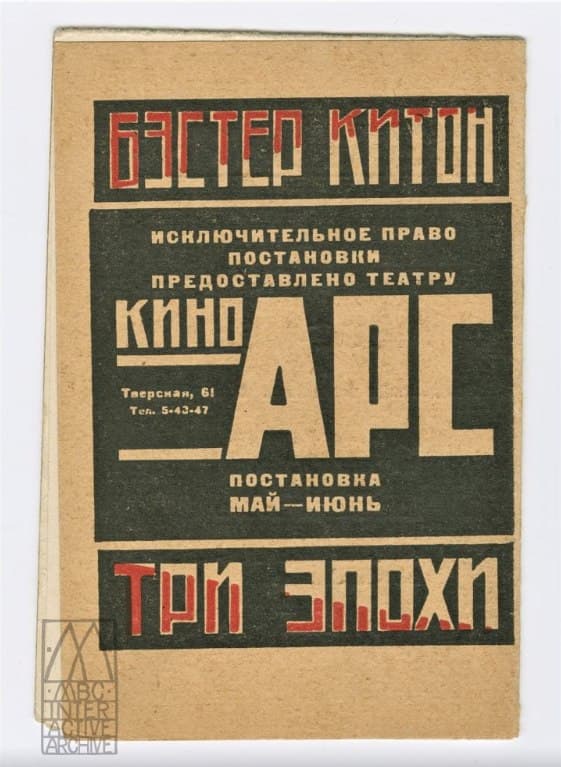

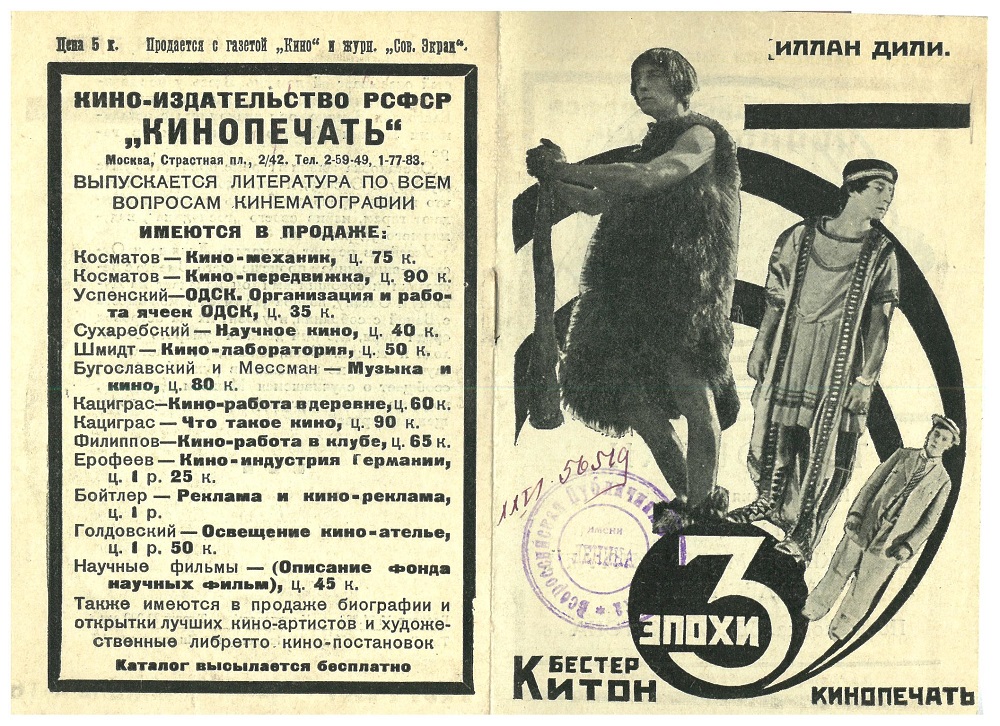

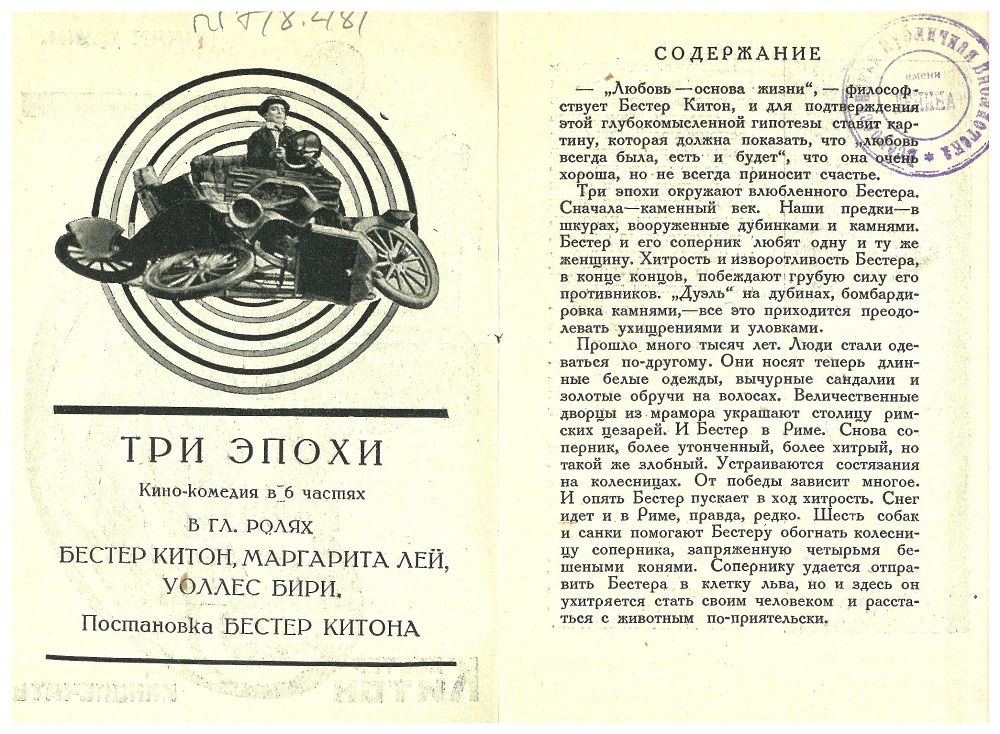

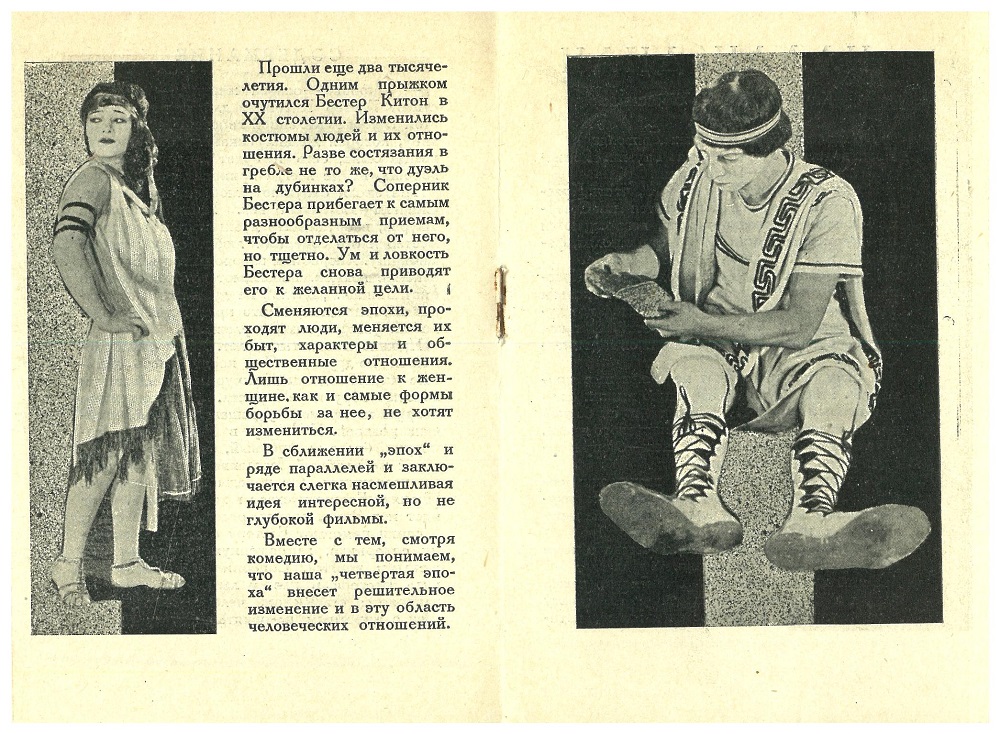

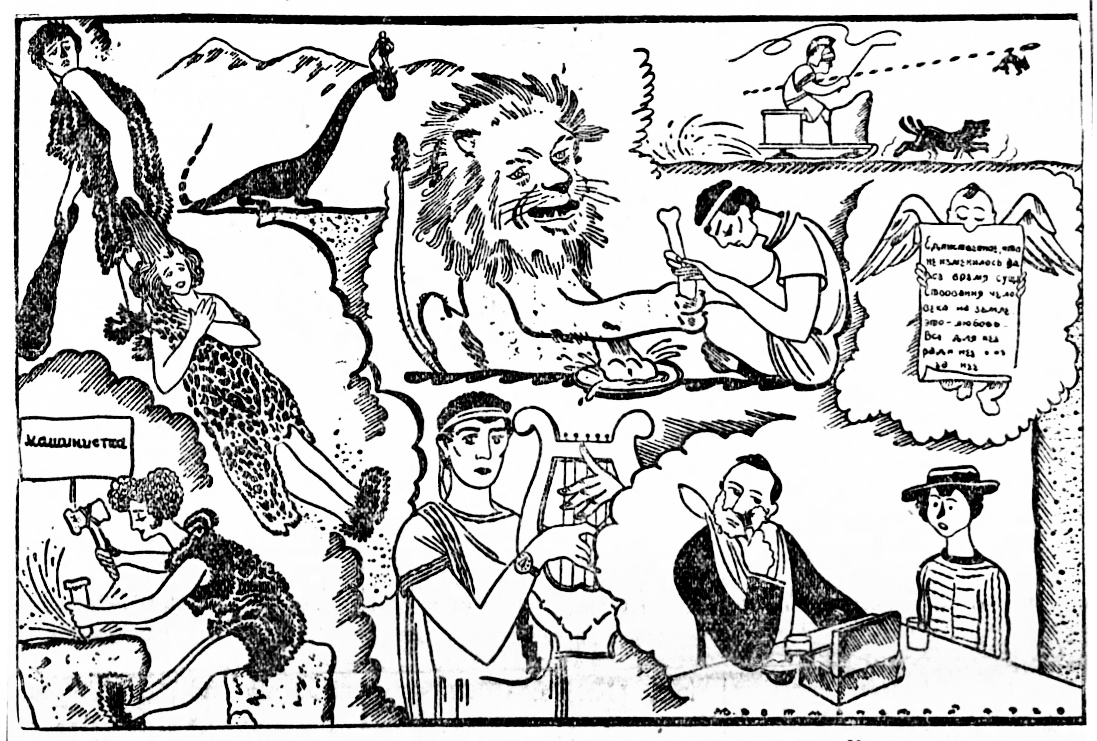

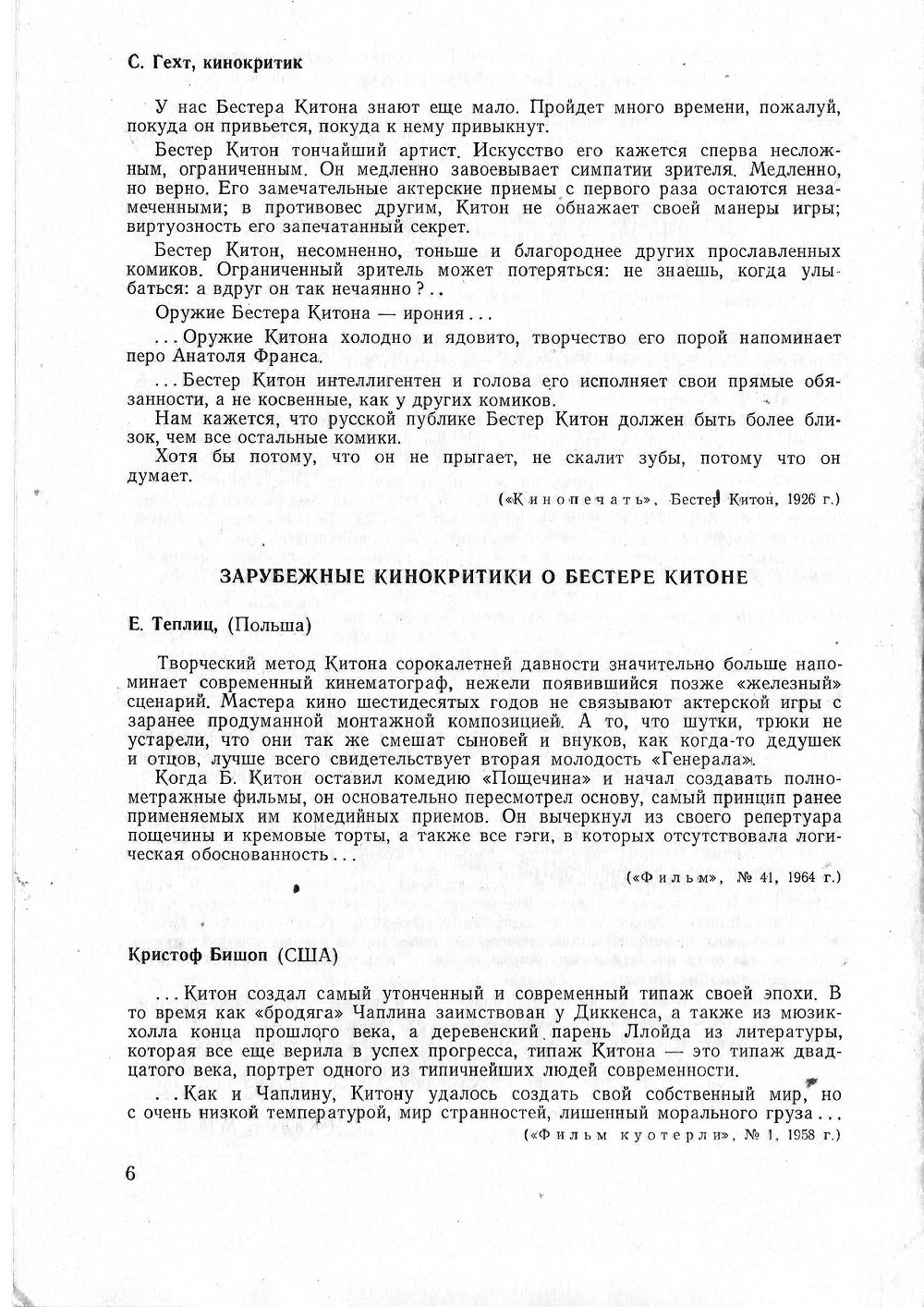

Три эпохи

(Three Ages)

Released on 21 May 1926?????

A Ukrainian poster.

This is a really nice poster design. Again, it seems to be not an official poster, but rather a poster designed by a local cinema. Very clever. I like it. Who was the poster artist? There is some writing at the bottom but it is far too tiny for us to read.

Who created this lobby card?

This time, Keaton is spelled Кейтон rather than the usual Китон. |

|

The Russian Buster group kindly supplied me with yet another publicity brochure:

|

|

|

And another:

|

|

|

And still another:

|

|

|

And more besides:

|

Source unknown  Жизнь искусства (The Life of Art) (№39) 28 September 1926 _1926-06-01.jpg) Кино, еженедельная газета (Kino, Weekly Newspaper), 1 июня 1926 (1 June 1926), №22 (142) _1926-06-08.jpg) Кино, еженедельная газета (Kino, Weekly Newspaper), 8 июня 1926 (8 June 1926), №23 (143)  Советский экран (Soviet Screen) №25 |

|

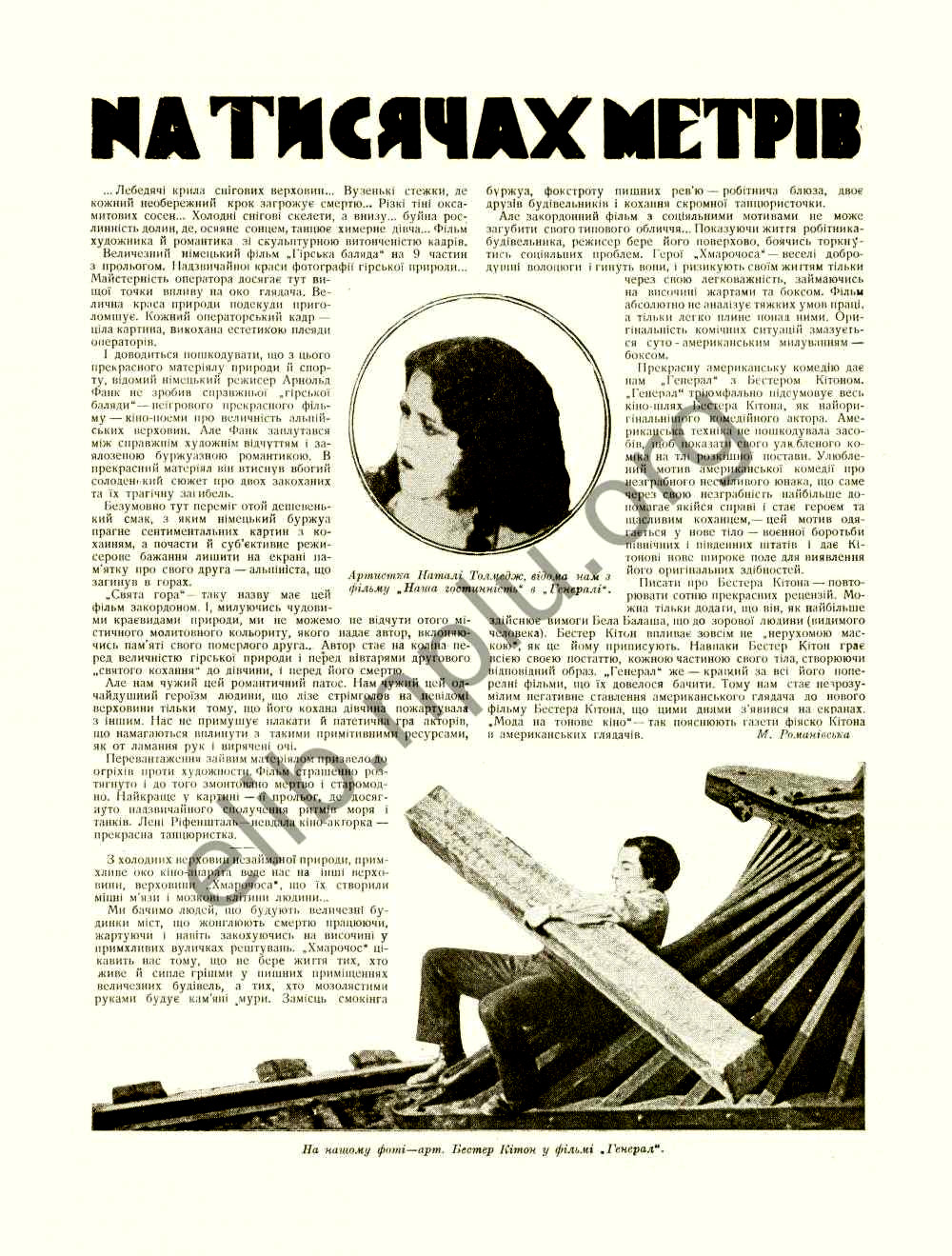

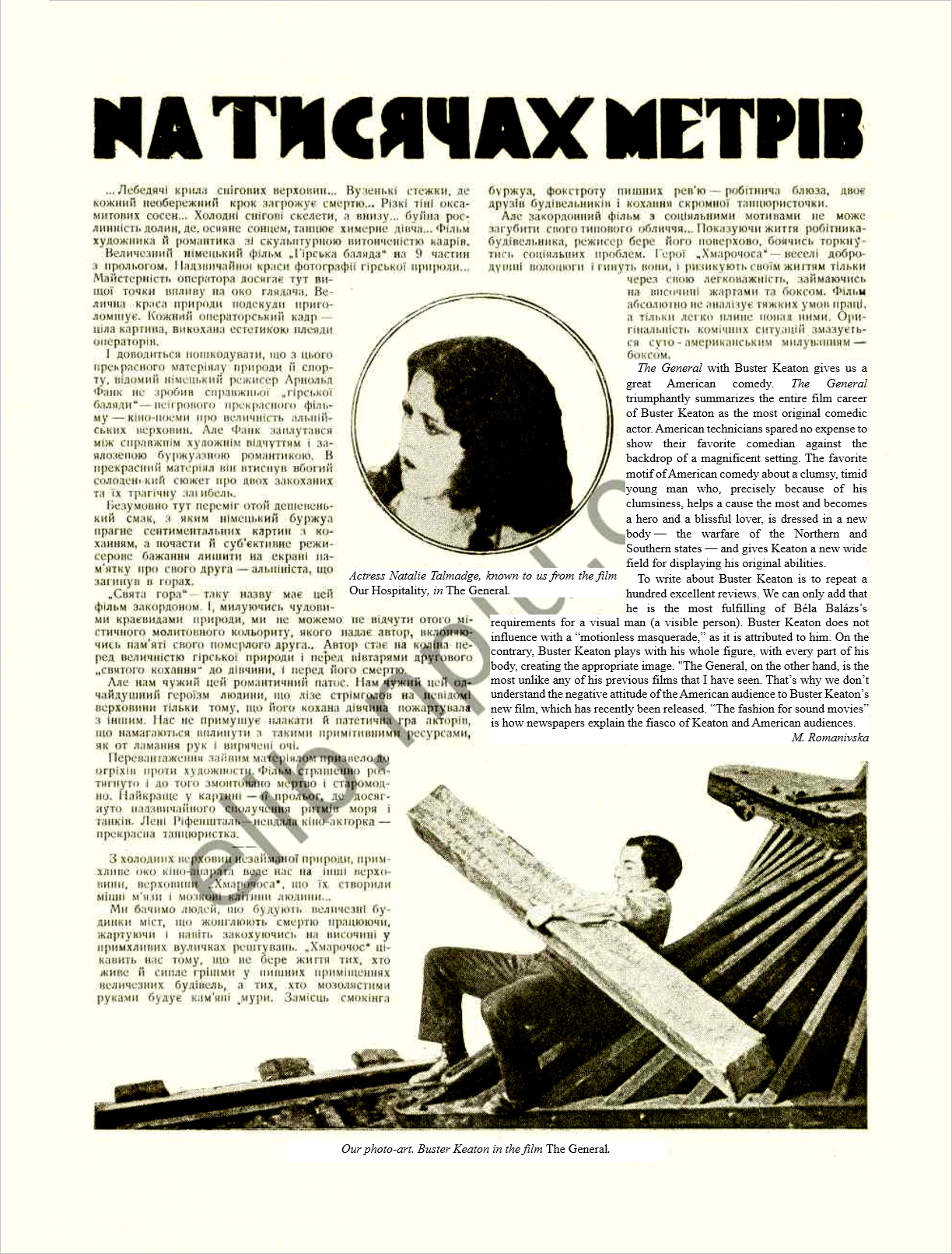

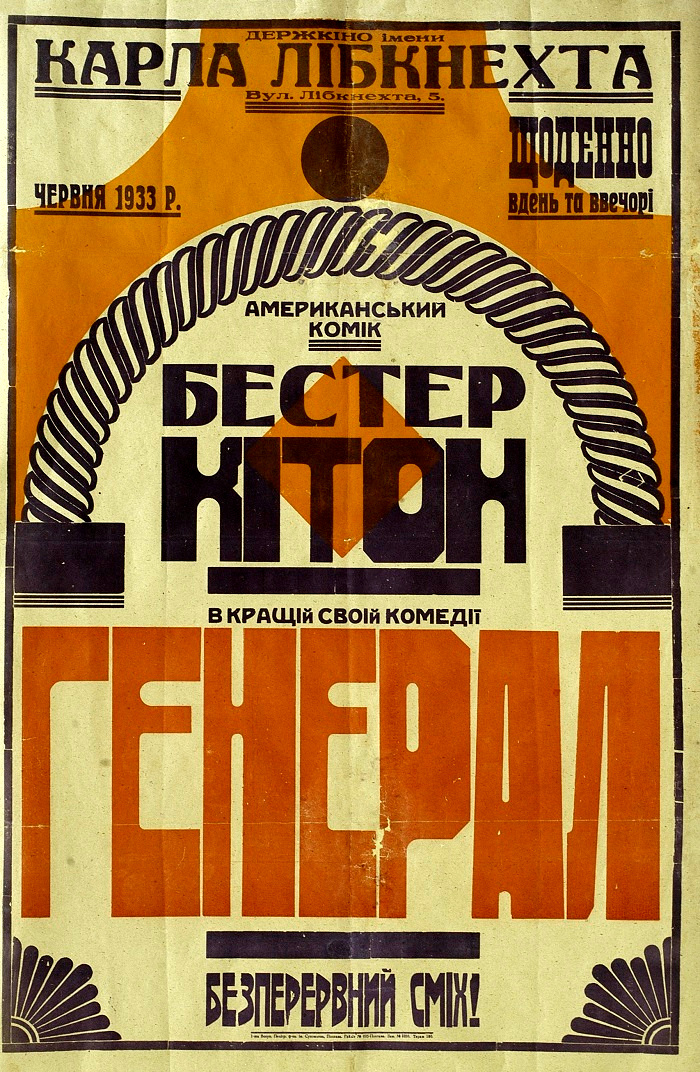

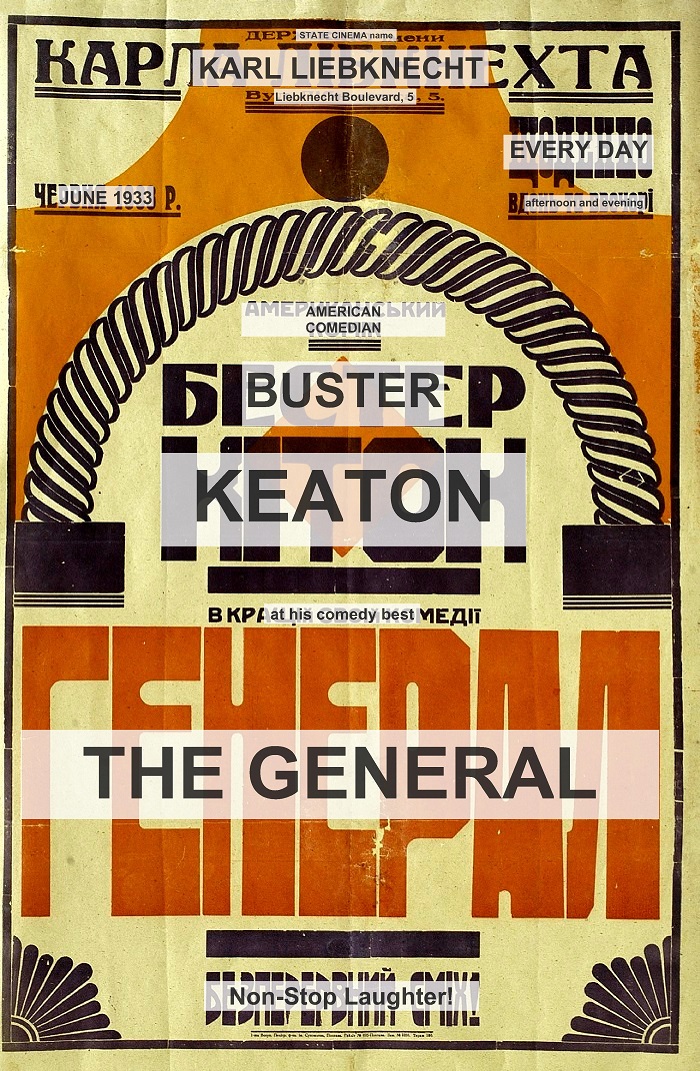

Генерал

Distributed by Sovkino.

Released on 1 June 1929?????

(The General)

Both of the above posters are by the great Stenberg brothers.

|

|

My colleague is certain that The General was released in Moscow sometime in 1928,

and that it spread to other parts of the Soviet Union in 1929.

Further, it was an official licensed release!

Joe Schenck was in Moscow in August 1928 and brokered a deal.

My head is spinning.

She says more besides:

|

|

As for reviews, by the time The General was released in the USSR (1928),

the press in general had switched to Soviet film production —

the NEP period was coming to an end,

so press coverage of foreign cinematography had virtually ceased compared to the

|

|

That boggles my mind.

A reviewer in Ukraine, in 1929, heard that US audiences rejected The General?????

As you could see earlier on, the reverse was true.

Audiences loved The General,

so much so that it was occasionally held over or brought back,

so much so that at least four cinemas reported that it was the biggest moneymaker of the fiscal year,

and so much so that United Artists kept it in circulation for five years in the US

and more than ten years in the UK.

That is hardly rejection.

Yet we do have to remember that single sentence in

Variety, vol. 89 no. 12,

Wednesday, 4 January 1928, p. 8, which stated that

“Buster Keaton had a few [releases] but they got nowhere.”

On an earlier page, I proferred a possible explanation for that bizarre sentence.

Further, it seems to have been the case that, regardless of profits,

the contract had United Artists serve not as an investor, but merely as a distributor,

which meant that it earned not percentages but mere distribution fees.

That is almost certainly what “nowhere” meant.

Is that the sentiment that was conveyed to the Ukrainian journalist?

I need to get a copy of that review!

|

|

Ah! Here it is!

|

|

|

Here it is again, with the relevant text Englished:

|

|

|

Oh. Wait. It wasn’t just UA saying that Buster’s films went “nowhere.”

Romanivska’s source had to have been Martin Dickstein’s 13 February 1927

defense of his positive review of six days earlier.

Dickstein claimed, wrongly, that NYC critics “were almost unanimous in the

opinion that the film at the Capitol was not only lacking in merit but that

it was as humorless a performance as the frozen-faced Mr. Keaton has ever demonstrated.”

Where on earth Dickstein got that idea, I know not.

The NYC critics were not unanimous.

Some loved the movie, some thought it no great shakes, and some fell in between those two extremes,

just like with pretty much every movie.

There could not possibly have been any other direct source for Romanivska.

Then, strangely, Rominivska continues by claiming that

“‘The fashion for sound movies’ is how newspapers explain the fiasco of Keaton and American audiences.”

Though I have not found every review and every commentary and every letter to the editor,

I have found quite a lot, and nothing, NOTHING, even hints at such an explanation.

Methinks that someone was feeding Romanivska some bad intel.

What is so odd is that there was no “fashion for sound movies” at all.

A couple of talkers made a profit, and so the studio bosses, not wanting to trail behind in the marketplace,

made a decision to shut down silent productions and switch exclusively to sound,

and that was one of the dumbest business decisions that the world has ever witnessed.

Cinemas fired their musicians and ripped out their massive pipe organs and bashed in their orchestra pits,

and that was the end of an era.

|

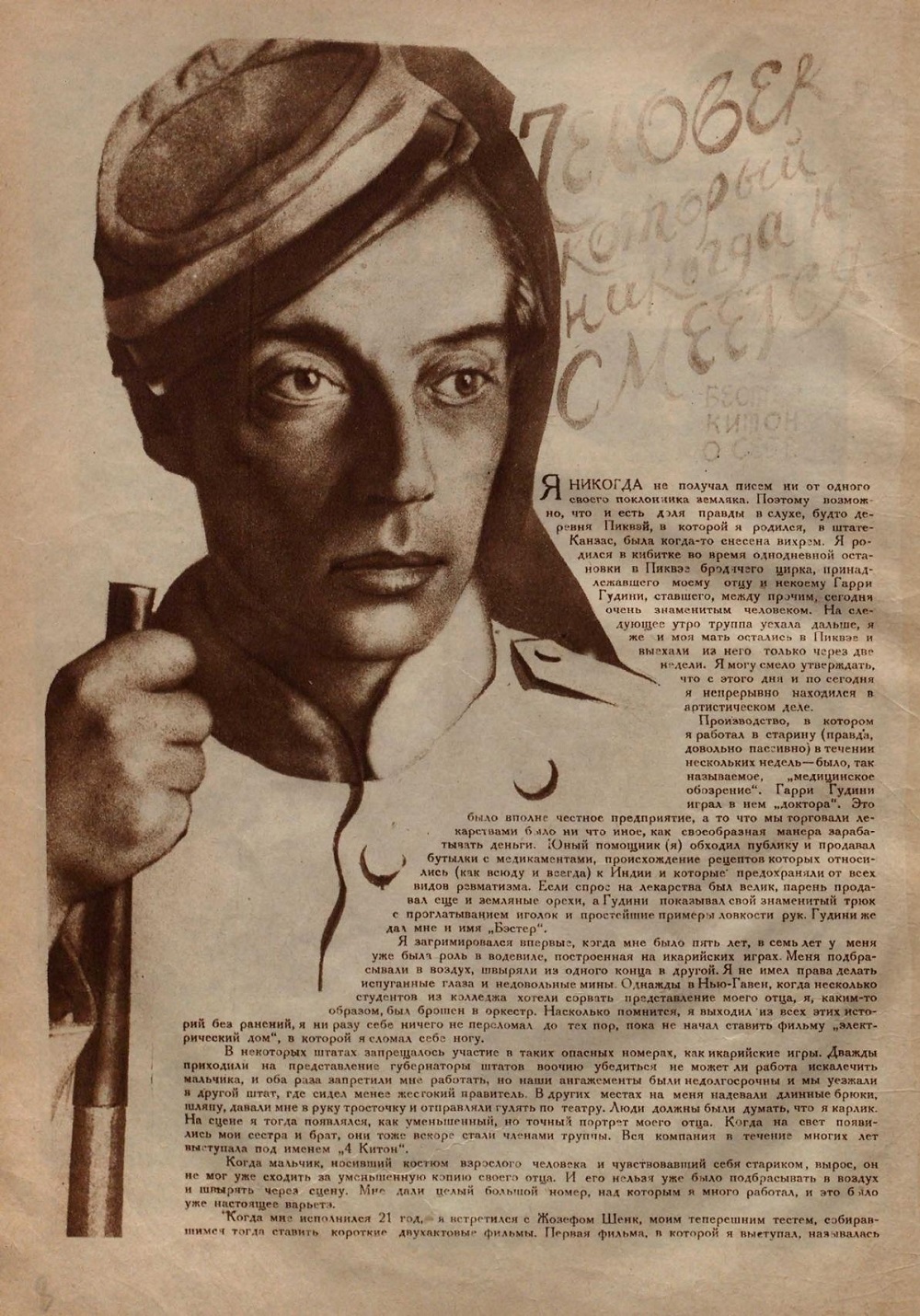

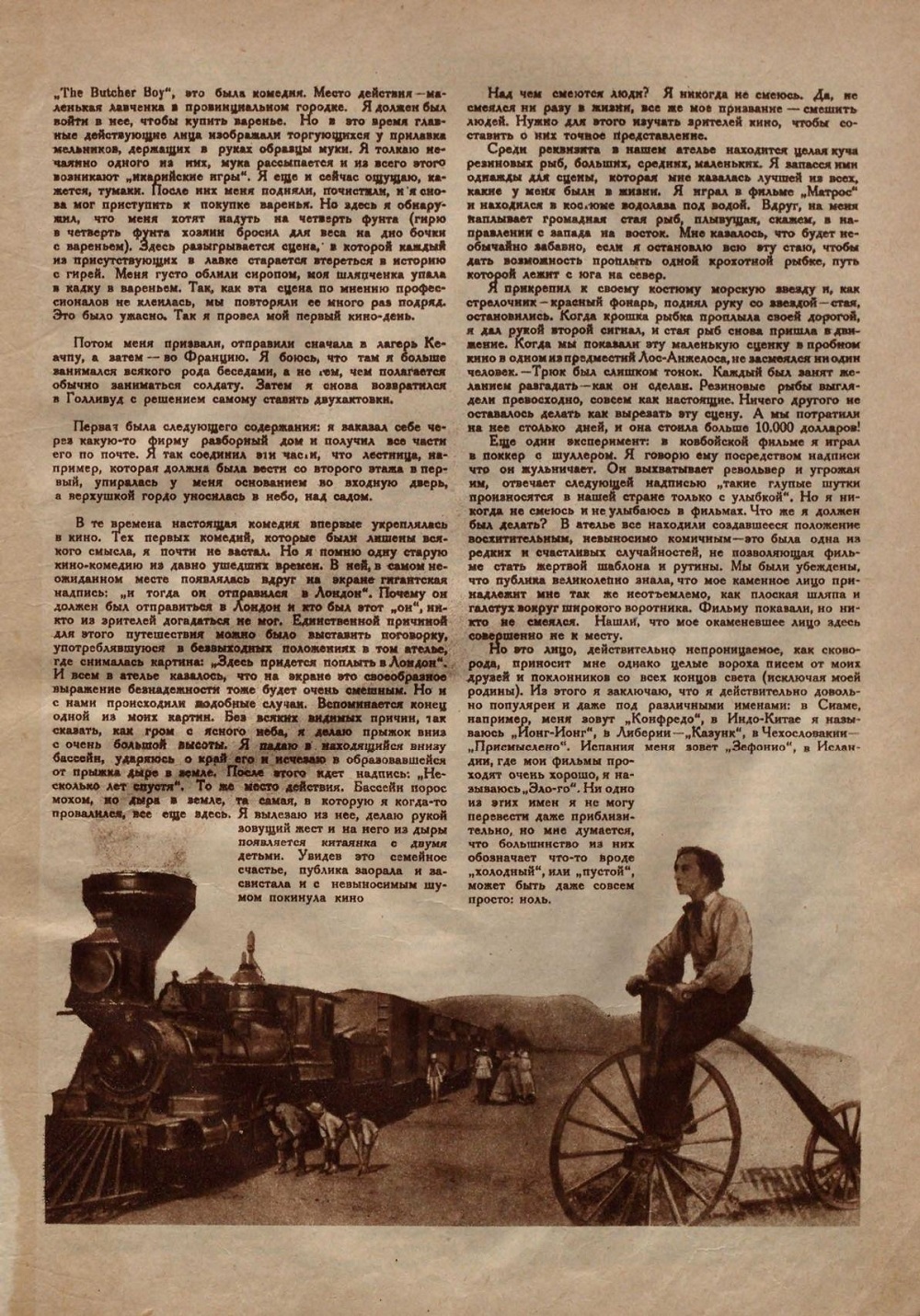

The above is from Советский экран (Soviet Screen), and it is Buster’s usual story as transcribed, copy-edited, and polished by Harry Brand.  Кино и культура (Cinema and Culture) (№1), just a passing mention.  Жизнь искусства (The Life of Art) (№40) |

|

Shall we ask a Smartphone and DeepL to help out?

|

|

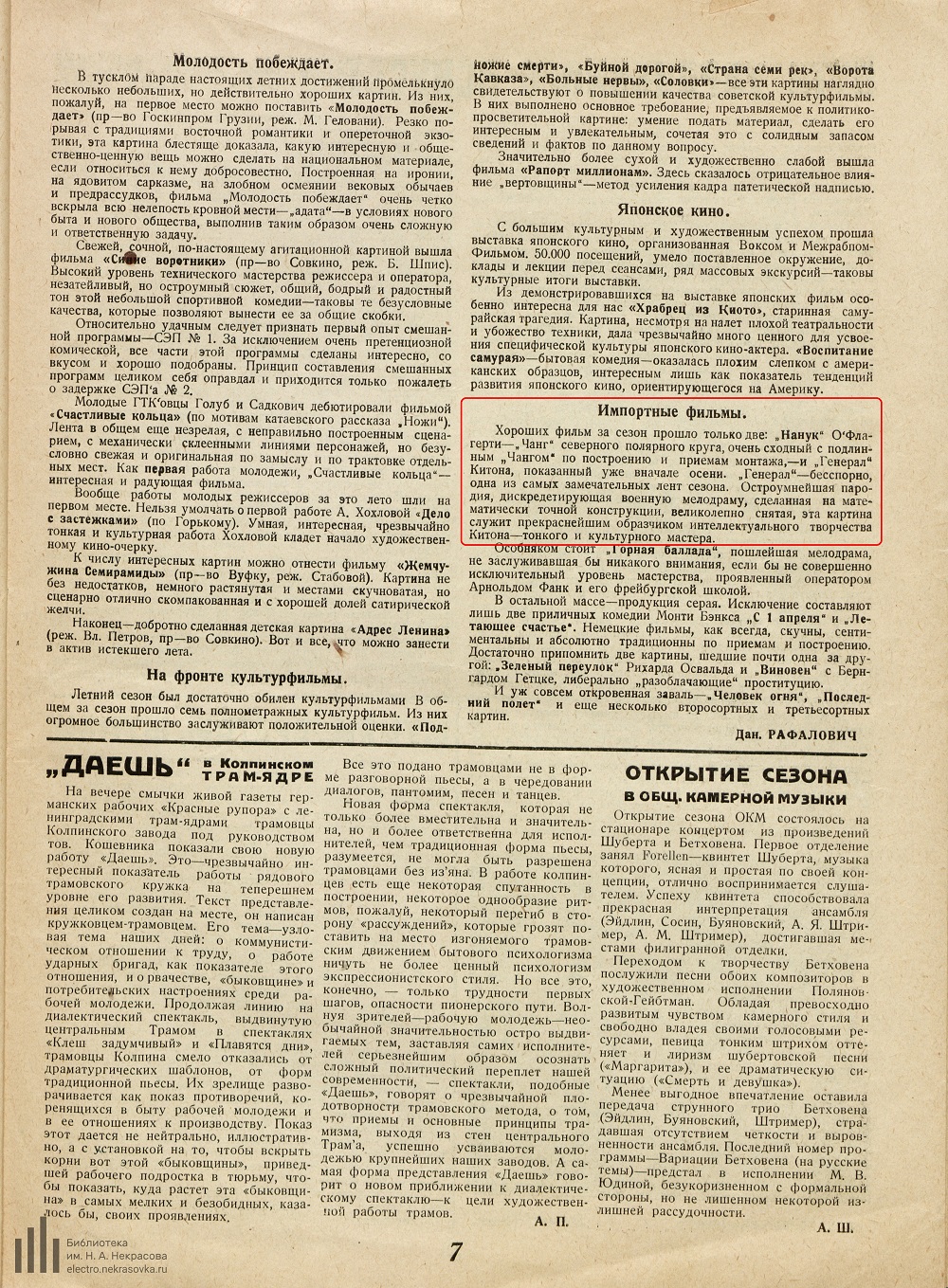

Импортные фильмы.

|

Imported Films.

|

|

Хороших

фильм

за

сезон

прошло

только

две:

„Нанук“

О’Флагерти-,

„Чанг“

северного

полярного

круга,

очень

сходный

с

подлин

ным

„Чангом“

по

построению

и

приемам

монтажа,

-и

„Генерал“

Китона,

показанный

уже

вначале

осени.

„Генерал“-

бесспорно,

одна

из

самых

замечательных

лент

сезона.

Остроумнейшая

пародия,

дискредетирующая

военную

мелодраму,

сделанная

на

математически

точной

конструкции,

великолепно

снятая,

эта

картина

служит

прекраснейшим

образчиком

интеллектуального

творчества

Китона-тонкого

и

культурного

мастера.

|

There were only two good films for the season: O’Flaherty’s Nanook,

a “Chang” of the northern polar circle,

very similar to the original

Chang

in construction and editing techniques;

and Keaton’s The General, shown in the early autumn.

The General was undoubtedly one of the most remarkable films of the season.

A witty parody, discrediting military melodrama,

made on a mathematically precise construction,

beautifully shot,

this picture is the finest example of the intellectual work of Keaton, a subtle and cultured master.

|

|

The General remained in circulation through 1933, by which time the New Economic Policy was over,

and that was the end of that.

|

Englished:  The fine print at the bottom? Sheesh. Too blurry. If you are Ukrainian, see if you can decipher it:  If you can, please drop me a line. Thanks!

This was one of the last bookings.

The poster was designed by the Karl Liebknecht State Cinema, which I think was in Chernobyl,

and the booking was for the entire month of June 1933.

I suspect that the movie was revived as a final fond farewell.

|

|

|

|

To demonstrate how popular Buster (and Charlie and Harold and Mary and Doug) were in Russia,

she pointed out this little film from 1927, One from Many,

which, sadly, was transferred to video incorrectly, losing the height as well as the left side.

Watch it anyway:

|

|

Классика советского кино (официальный канал), Одна из многих (1927) фильм, posted on Dec 25, 2016. When YouTube disappears this, download it. |

|

To make it even juicier, she sent me the following link, showing how Buster influenced Soviet animation:

|

|

Formanta Formantova, „Ну, погоди!“ и Бастер Китон, posted on Nov 6, 2022. When YouTube disappears this, download it. |

|

Where and when did the films play?

Were there newspaper advertisements?

Were there reviews?

Were there

|

|

MORE IMPORTANTLY:

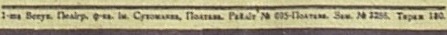

The General was reissued in the Soviet Union in 1963, probably together with Cops.

The evidence for that is in the above news clipping.

Who distributed this?

Precisely when?

Which cinemas played it? When? For how long?

Advertisements? Publicity materials?

|

|

|

Except... maybe not!

I just heard from a Russian researcher who spent forever trying to trace

any vestige of information about this 1963 release but came up blank.

There were no more screenings of any silent Buster movies in the Soviet Union until 1971,

when there was a retrospective in Riga, Latvia.

There are no contemporaneous references to a 1963 reissue.

What’s more, when It’s a Mad, Mad, Mad, Mad World

premièred in the USSR in 1966,

Buster was mentioned in a press release as someone that old-timers would remember from the 1920’s.

There was not a syllable about revivals of any of his silent films being show at any time in the 1960’s.

We shall see the review of It’s a Mad, Mad, Mad, Mad World

as well as the Riga program below.

|

|

So, that settles it.

That’s why I could never find any further info on this reissue.

It never happened.

If a Soviet distributor licensed it, then something went wrong and the release was abandoned.

|

|

As promised, here it is.

https://busterkeaton.ru sent me this clipping

from Soviet Screen, January 1966, to tie in with the current release of

It’s a Mad, Mad, Mad, Mad World.

As stated above, this article reminisces about the only four Buster movies that old-timers would have seen,

and gives the distinct impression that Buster had not been seen in more than 30 years.

|

|

|

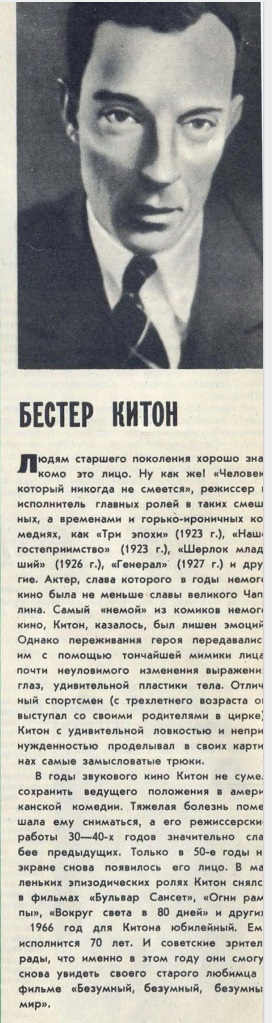

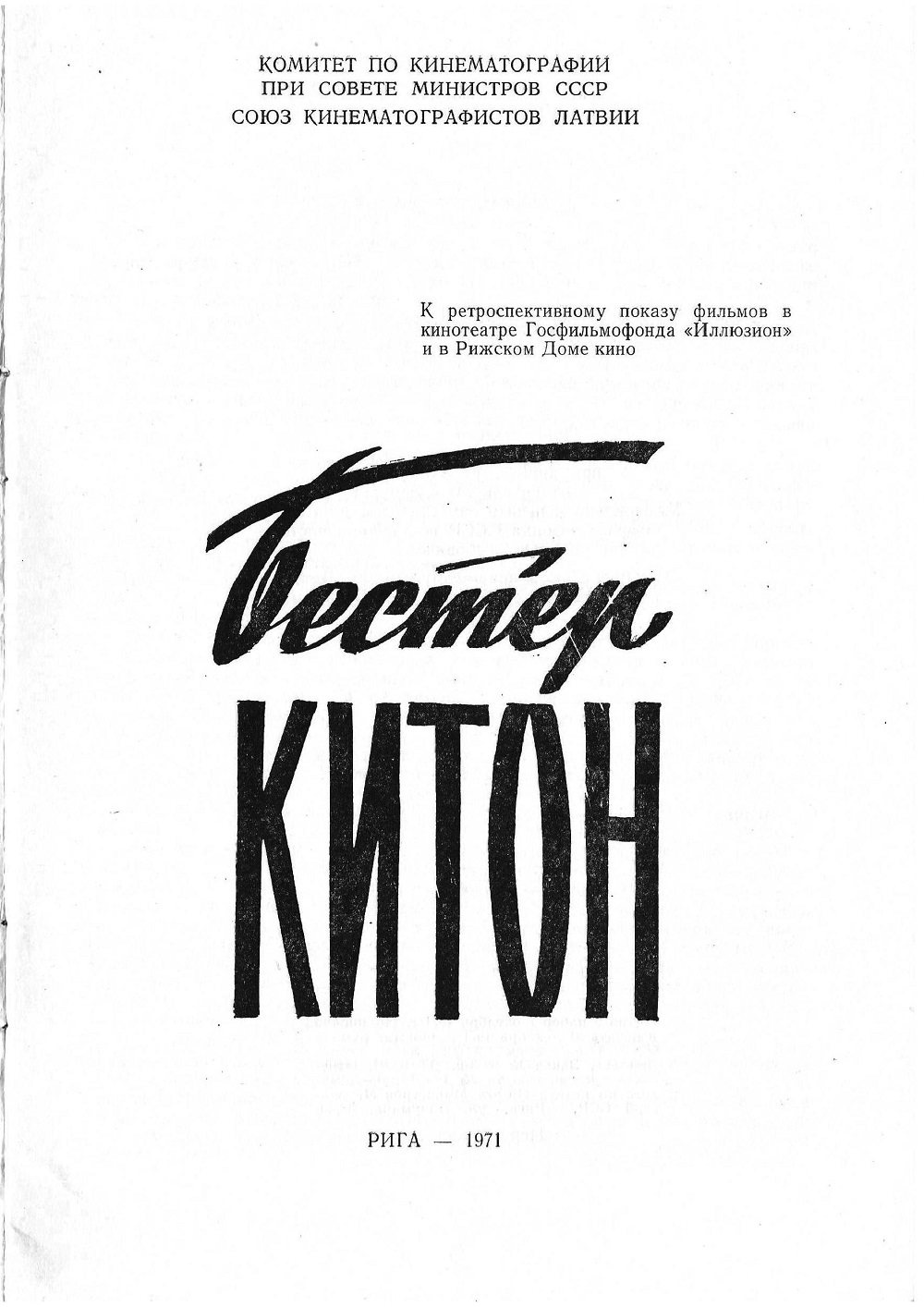

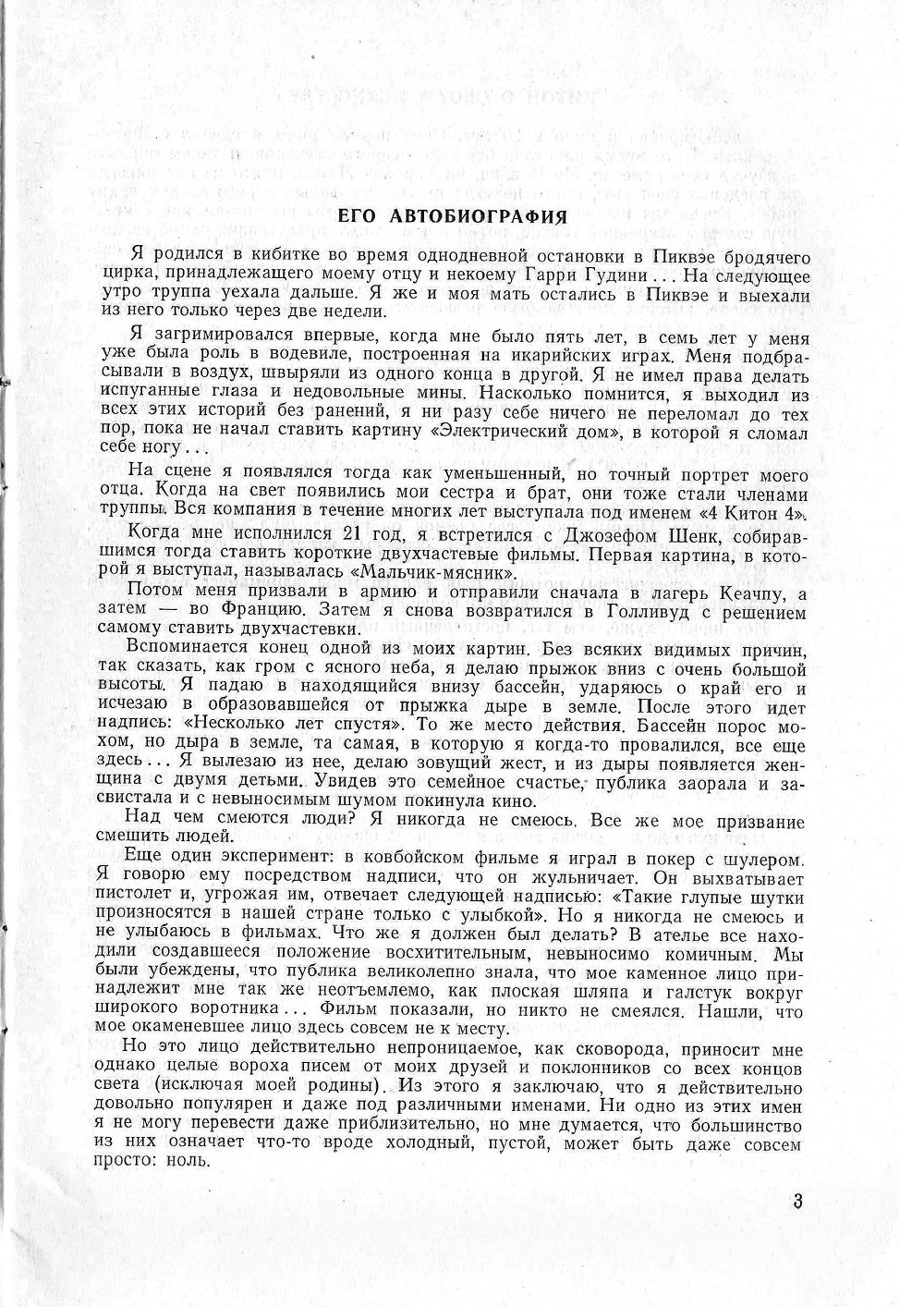

And here, as promised, is that 1971 program from Riga, Latvia.

This was the first time any of Buster’s movies had been seen anywhere in the Soviet Union in 40 years.

|

|