|

George Mitchell, film historian, on visiting film collector George Marshall,

as told to Anthony Slide, Nitrate Won’t Wait: A History of Film Preservation in the United States

(Jefferson, NC: McFarland, 1992), p. 46:

At the New Yorker Theatre on Sundays [William K.] Everson would run silent

pictures, 35mm stuff. He used to go down to Lloyd’s Film Storage — he had some

sort of connection with Lloyd’s Film Storage — and he would come up with 35mm

stuff you just can’t believe....

|

K27-74, K27-196, K27-206

|

|

This was issued on 30 October 1989 and my copy arrived in the mail I think in November 1989.

It confused me.

My VHS is somewhere in my storage locker, and so, pending my recovery of it,

I am watching and rewatching and rerewatching a library’s copy.

My conclusion: It STILL confuses me.

|

|

The irony?

I spent ages trying to find a library that had this,

and I found a library, a university library that would not allow nonstudents or nonfaculty to check items out.

So, I got written permission from Kino,

and then the library agreed to supply me with a digital copy that would disappear after six months.

Their staff took, I think, two weeks to scan the cover for me. Hooray.

Better yet, along with the cover came the digitized VHS tape.

The friendly librarian gave me the secure password-protected link with a nondownloadable video at the other end of it.

Then, of course, I discovered that a better copy was freely posted, legally, on the Internet all along:

|

|

Whoops! The above embed may no longer work.

Let’s try this one:

|

Now, this is not exactly the same.

This is a 16mm print that has some scratches and dirt that were not on the 35mm print that Kino sourced.

Nonetheless, both the 16mm here and the 35mm that Kino sourced derive from the identical submaster.

Further irony: Another copy is posted on YouTube at

https://youtu.be/ksxYGC0-Mfs.

Hmmmmm. An IMAGES Film. Hmmmmm. Seems awfully familiar.

I had run across that name before, æons ago.

I seem to remember that Bonaparte and the Revolution was An IMAGES Film.

Well, lo and behold, IMAGES Archive was

Bob Harris’s company!

|

|

The 35mm print that Kino sourced definitely traced its ancestry to MoMA, seemingly to a lavender,

which indicates to me that one of the two positives there really was a lavender.

It was not a dupe of the projection print.

There are no cue marks of any sort, and that is not because they were digitally removed.

This is an analogue transfer.

My best guess is that this is a dupe of a newly made print from MoMA’s copy negative.

All eight reels were cement spliced together onto two larger reels and

there seems originally to have been no change-over,

but just an intermission while the operator loaded the next reel.

There are a few frames missing that are not missing from other copies.

|

My best guess is that this is William K. Everson’s print.

Everson mostly collected 16mm, but I bet he collected a little bit of 35mm, too, when the opportunity arose.

He was still alive at the time and he loaned his materials out for home editions.

Everson was known to snip clips out of his prints to assemble them into compilations for lectures,

and then to splice the pieces back together later on.

That could explain the few frames missing at every join here and there.

Why is this print flickery?

Flicker would not be evident in a second-generation print.

So this must be a third-generation print.

This has to be a copy of the MoMA material.

Somebody else managed to run off a print from MoMA’s copy negative,

and then somebody duped that print,

and that dupe somehow ended up with Bill Everson.

That’s the only explanation I can think of.

If you know more than I do, please give me a holler.

|

|

So, Everson got a dupe of someone else’s copy of the film, but whose?

Rohauer’s? No, they were not exactly on speaking terms, and anyway,

Rohauer duped the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences’ nitrate print,

not MoMA’s material.

Killiam’s?

No, because Killiam somehow borrowed MGM’s fine grain, not MoMA’s material.

John Griggs? No, Griggs duped MoMA’s 16mm circulating print.

Joe Franklin? Maybe. Joe Franklin managed to get copies of MoMA materials, and maybe he collected 35mm?

I don’t know.

If Joe Franklin had a 35mm print, he might have arranged to dupe it for Everson. Maybe.

We’ll probably never know.

|

|

If it’s Everson’s print, that would explain why the box cover states,

“MASTERED FROM 35MM ARCHIVE PRINT,” without letting us know which archive.

That would make perfect sense if it’s from a private individual’s archive

that was gathered by rather iffy dealings.

|

|

For what it’s worth, the techies zoomed right in to the center of the frame and lopped off all four sides.

Gaylord Carter’s organ score, by the way, was recorded by Robert Harris in 1978,

for his IMAGES Film 16mm edition derived from MoMA’s master.

It was David Shepard who used that recording 11 years later for this Kino VHS edition.

It’s an interesting score, and as I listen to it repeatedly on continuous loop,

I am at last able to articulate what I have so often heard at the cinema.

Gaylord had seen the movie before, plenty of times, and he had some good ideas about which period tunes he would include,

and he got some of the sound effects spot on, but there is something else going on, too.

He did not plan this accompaniment out on paper.

He winged it, and he knew he could.

He used the tricks that other accompanists use:

playing a couple of notes repeatedly just to fill the time until the next obvious cue appears.

That is why his score is not catchy, not hummable.

Much of it is just empty filler.

So, it’s not a great score, but that’s okay,

because it is a perfectly representative example of what organists would have done back in the day.

This is as vintage as vintage can be.

It’s probably not much different in mood and flavor

from the organ accompaniments during the three test screenings in October and November 1926.

Also, I must say that, on video, Gaylord’s scores seem pretty lame.

Then I heard him live, at a Lutheran church in downtown Buffalo,

playing the church organ to accompany The Hunchback of Notre Dame, and he totally blew me away.

His boundless energy was infectious, and he made that whole building dance.

Hearing his recordings is nothing at all like hearing him live.

Why the recordings lost his energy, vitality, and sense of fun, I do not understand.

Also, Gaylord, who was a mere ten years younger than Buster, interpreted the film the same way Buster interpreted it,

not as a grand, stirring, rousing epic of adventure,

but as a small, light-hearted diversion designed to provide a few laughs.

|

This is the final title on the VHS tape.

|

|

This bizarre specimen is housed at the Cottage Grove Historical Society.

Who assembled it and when, I do not know.

It confused me for a few hours, but then my thoughts began to clear.

It is a 16mm dupe, with the image extremely enlarged, causing the loss of all four sides.

For the most part, it is a dupe of a Blackhawk print of Killiam’s edition,

and we can recognize Killiam’s distinctive tears, splices, scratches, dirt on the negative, and sloppily remade cement splices.

Some bits and pieces that were missing from Killiam’s edition are missing in this one as well.

Other bits and pieces that were missing from Killiam’s edition are filled in!

Only some. Not all.

Some parts that were out of sequence in Killiam’s edition are still out of sequence.

Other parts that were out of sequence in Killiam’s edition are here back in sequence.

Except for the main title credit, the opening credits are restored.

|

|

What happened?

Simple.

Somebody made a dupe neg of the Blackhawk print and a dupe neg of the Tarbox print,

and tape-spliced the two dupe negs together.

Whoever did this noticed only some of the differences, not all of them.

As for the usual mess in Reel 5,

the shots were put back into the correct sequence,

but the shot with the 22-frame gap, well,

the entire beginning was chopped off, as usual, to hide the jump in the action.

In the Tarbox edition, that shot is complete.

|

|

The person who spliced the two elements together did the job backwards.

The sensible solution would have been to use the Tarbox print as the template,

and then to cut in any Blackhawk scenes that looked superior.

Instead, the person at the splicing bench used the Blackhawk print as the template,

and filled in some gaps and performed some re-editing based on the Tarbox print.

Why?

That confused me, but then it occurred to me.

I know exactly what happened.

The person who did this was intimately familiar with the Blackhawk print

and was surprised to see some differences in the Tarbox print.

That person, whoever it was, thought that the Blackhawk print could be repaired with the Tarbox print.

|

|

The opening title and the closing title were replaced.

Why? To hide the evidence.

The Blackhawk and Killiam main and end titles are all distinctive replacements.

So whoever hammered this dupe neg together hired a technician to film a new opening title

and then searched about for a generic End title from some other movie,

duped it and spliced it in to this movie.

For some reason, the person who performed these surgeries

did not think to use Tarbox’s titles, which were (poorly) copied from the originals.

|

Tarbox (copied from the original)

|

Killiam |

Blackhawk

|

Cottage Grove Historical Society

|

Tarbox (copied from the original)

|

Killiam |

Blackhawk

|

Cottage Grove Historical Society

|

|

Nothing is ever that easy to solve, though.

I just purchased on eBay a home-made VHS tape of The General

that opens with the same title that opens the Cottage Grove Historical Society’s print.

This tape was made by pointing a video camera at a screen

while a mute three-reel 16mm print was projected at 24fps.

It is not exactly the same at the 16mm print at Cottage Grove.

For instance, when Johnnie is kicked out of the recruitment office,

we do not see the splice mark that is so visible on the Killiam prints.

There are a few other small differences as well,

concluding with a different replacement “The End” title.

So we can conclude that it was not the Cottage Grove Historical Society that assembled its 16mm print.

The CGHS purchased the composite from some other firm,

a firm that had revised its edition at least once.

Where was the print purchased?

What can we learn about that print?

|

|

Curiously, what appears to be an 8mm equivalent is on eBay:

|

The public domain is a topic that

seems to confuse a lot of people,

including educated people who should know better.

I am not an expert on this topic, but I do have some limited understanding of it.

Yes, if you are digging through your great-grandma’s attic and stumble upon eight cans of an original 1926 print of The General,

you are legally free to make copies of it, because there is no copyright claim to the underlying work.

You are legally free to clean it up, digitize it, stabilize it, color-correct it, compose music for it,

and issue it on Blu-ray or on streaming services or show it at cinemas.

It does NOT follow that anybody else would be free to duplicate your cleaned-up, digitized, stabilized, musicalized edition

and offer it on Blu-ray or on streaming services or show it at cinemas.

When you cleaned it up, digitized it, stabilized it, color-corrected it, and composed music for it, that was YOUR work,

and nobody has the right to duplicate it.

If your neighbor cleans out her great-grandma’s attic and stumbles upon eight cans of an original 1926 print of The General,

your neighbor has the legal right to clean it up, digitize it, stabilize it, color-correct it, compose music for it,

and issue it on Blu-ray or on streaming services or show it at cinemas.

If you like your neighbor’s results better than your own results, you do NOT have the legal right to copy your neighbor’s version.

If you are on staff at a cinema that is showing the Rohauer Collection’s latest DCP restoration,

you do NOT have the right to make a copy of it, no matter that the underlying work is in the public domain.

The restoration performed for the creation of that DCP is copyrighted and protected by law.

The General is in the public domain,

but if you want to make a video from the Rohauer Collection’s latest restoration of the camera negative,

you have to pay the Rohauer Collection for that access.

And the Rohauer Collection has the legal right to tell you to “Go away, we don’t want to play with you.”

If you purchase a film print of the 1972 Rohauer version from an antique shop,

you do NOT have the right to issue it on Blu-ray or on streaming services.

You do not even have the right to show it at your local public library, even if you don’t charge an admission fee.

If you decide you really like Lobster’s reconstruction of The General,

you do NOT have the right to copy it and issue it on Blu-ray or on streaming services.

If you like Lobster’s version and want to distribute it, you need to hammer out a contract with Lobster.

You have no case if you cry to the judge that, “But Your Honor, it’s in the public domain.”

The judge would sentence you to be hanged from the nearest tree.

Lobster’s reconstruction work is Lobster’s and nobody else’s.

If you rent a museum’s copy of the movie, and if the rental contract contains a stipulation that you will not copy the movie,

you had better not copy the movie.

If you do copy the movie, expect the museum to sue the living daylights out of you.

It does not matter that the movie is in the public domain; you have breached the contract, and you are legally liable.

A contract prevails over a public-domain status.

The underlying work is free and clear of all copyright claims.

The various reconstructions, restorations, and musical scores are most definitely protected by copyright.

MoMA, the BFI, Ray Rohauer, and Jay Ward obtained their copies and their rights legitimately.

KirchMedia did everything legally.

|

Movie distribution in previous decades, though, was a bit of a Wild West.

If distributors could get away with it, they would, and they did.

Mostly they danced just outside the limits of the law, but not far enough outside the limits of the law that they risked lawsuits.

Since The General was in the public domain, it was available in countless duped copies,

each worse than the last, from a limitless number of fly-by-night vendors.

Some were so dark, washed out, and flickery that it was difficult to follow the action.

Even a legit distributor, Kit Parker, offered an unwatchable edition of The General.

I remember that

Ira Jaffe showed

Kit Parker’s

16mm print to his class at the UNM Rodey Theatre

and it was painful to sit through — just lots of flickering blacks interrupted by pasty-white faces.

Nobody enjoyed the result. Not a single chuckle. Horrible.

My memory is that Kit’s print was a dupe of a dupe of a dupe of a dupe

of a 200th-generation dupe of Rohauer’s 1972 version.

|

|

There were infinite 8mm and 16mm dupe editions from infinite distributors.

One I know about was:

|

|

Minot Films

Millbridge ME (issued in 1971).

|

John Griggs had a 16mm dupe, double-sprocket silent, copied from the MoMA 16mm circulating print.

When he passed away, Essex Films of Nutley, New Jersey, purchased his collection,

and Robert E. “Bob” Lee added sound effects and recorded Stuart Oderman’s piano score.

He submitted this for

copyright registration on 5 July 1977.

Jim Kartes later issued this on βetamax II and VHS.

It is now available on DVD from

ReelClassicDVD.com.

|

|

There was also the Thunderbird atrocity from 1972,

duped from the Killiam edition with inappropriate dance music on the soundtrack.

That’s not to mention the gawdawful Kit Parker atrocity mentioned just above.

Some others seem to have been:

|

|

When we look at Elliot Rubinstein’s Filmguide to The General

(Bloomington and London: Indiana University Press, 1973), pp. 80–81, we learn about a few more:

|

|

Clem Williams Films

623 Centre Ave

Pittsburgh PA 15219

Contemporary Films

Princeton Rd

Hightown NJ 08520

Cooper’s Classic Film Rental Service

Northgate Shopping Center

Eaton OH 45320

Em Gee Film Library

4931 Gloria Ave

Encino CA 91316

Radim Films

17 W 60th St

Manhattan NY 10023

Standard Film Service

14710 W Warren Ave

Dearborn MI 48126

and the predictable sublicensee for the university market:

Swank Motion Pictures

2151 Marion Pl

Baldwin NY 11510

Swank Motion Pictures

2015 S Jefferson Ave

St Louis MO 63166

Regarding copies for purchase, in addition to Blackhawk and Entertainment Films,

there was also:

Edward Finney

1578 Queens Rd

Hollywood CA 90069

Rubinstein opened his rental list, though, with Rohauer’s authorized distributor:

Audio Film Center

34 MacQuesten Parkway S

Mt Vernon NY 10550

a mere mile and a half from my unpleasant childhood.

|

Were there others, too?

If you can fill in any blanks, please do. Thanks!

|

|

Then there were infinite dupe video editions from infinite distributors.

In the late 1970’s I saw these beginning to ooze out from some subterranean crevice somewhere

and slowly seep into video shops, leaving behind them trails of slime.

Then there were more, and more, and more, and more, and just a few years later there were entire ravenous hordes,

entire invading armies of these PD dupes slithering their way into video shops everywhere.

I never wanted to look at them.

Their very existence offended me.

And now, more than four decades later, here I am, collecting them.

It’s terribly disheartening to examine these parasites that infested the market, but it is educational as well.

Until I started looking at these videos, I had just assumed

that there were countless original 1926 prints lying about and that various businesses found

them here, there, and everywhere, and then duplicated them.

How wrong I was!

There are only six branches on this family tree, and it is usually easy to figure out which branch each dupe fell from,

because there are always a few giveaways.

These are the six versions that the pirates copied,

and I point out the giveaways that you will see in any unauthorized copies:

|

|

NUMBER ONE — MoMA house print:

UA donated this nitrate print to the Harvard University Film Foundation in 1927,

which in turn donated it to MoMA in 1936.

This is the print that was shown on premises.

Most videos of this edition derive from Charles Tarbox’s 16mm dupe.

Giveaways:

• Brief intro crediting Harvard (this is deleted from some bootlegs).

• Original main title.

• Original copyright title.

• No gap in Reel 5.

|

|

NUMBER TWO — MoMA circulating print:

This was derived from a domestic lavender(?) that UA donated to the Harvard University Film Foundation in 1927,

which was in turn donated to MoMA in 1936, and reduced to 16mm in 1941.

Giveaways:

• Replacement main title.

• Original copyright title.

• No gap in Reel 5.

|

|

NUMBER THREE — The Glendale Alex Preview Print from November 1926:

James Mason discovered this in the spring of 1955 and donated it to AMPAS in January 1956.

In early January 1960, Rohauer made a dupe negative from this print.

Giveaways:

• Original main title.

• No copyright title.

• No gap in Reel 5.

• A few revised edits.

What on earth does that mean?

That means that Buster trimmed a shot, watched it on screen,

and then decided he had trimmed it too much.

So he put a little bit back in.

Cement splices were made by scraping the emulsion off the top or bottom of a frame and overlaying it,

and hence every splice necessitated the loss of at least one frame.

In this print, we see a few instances of a missing frame in mid-shot,

for example, this moment.

The original (Kino K669) is on the left,

and the Alex Theatre preview print, as transferred by Thames video, is on the right:

|

|

NUMBER FOUR — Killiam’s 1970 edition:

This derives from MGM’s fine-grain.

It was greatly tampered with and re-edited, as detailed in an earlier chapter.

All the main titles were replaced, several shots were deleted,

several shots were chopped up to result in jumps in the action,

parts of the movie were scrambled, and plentiful damage was faked

to make it appear that it derived from a battered release print.

Giveaways:

• Replacement credits.

• Missing, shortened, and scrambled sequences as detailed earlier.

• Several reset titles, minus wood-grain background.

• A shot in Reel 5 is drastically shortened to pick up immediately after the gap in the negative.

|

|

NUMBER FIVE — Rohauer’s 1979 edition:

This derived from the fine-grain that the Jay Ward crew had used in 1970.

Giveaways:

• New main title.

• No copyright title.

• Music credit added at opening and closing.

• Gap in Reel 5.

|

NUMBER SIX — An original tinted release print, nitrate, of unknown origin.

David Shepard used bits and pieces of this print for his 1995 edition of “The Art of Buster Keaton.”

Parts of this were retained for the Image Entertainment DVD and the Mont Alto DVD.

My best guess is that this was Buck Manbeck’s print,

the one he showed in and around Des Moines back in the 1950’s and 1960’s.

Where did he get it?

My best guess is from a disused exchange.

Des Moines was, I think, on the Chicago exchange,

and the United Artists Chicago exchange, as of 1930, was at

804 South Wabash Avenue.

I know NOTHING, absolutely NOTHING about the history of that exchange.

Could anybody fill me in?

Giveaways:

• Original main title.

• Original copyright title.

• Lots of oxidization in some shots.

• Some titles are dark, flickery, and wobbly.

• No gap in Reel 5.

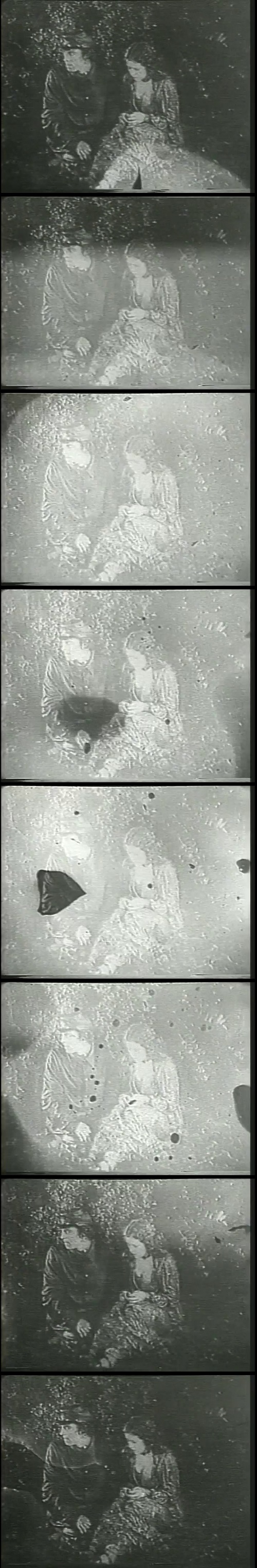

What do I mean by dark, flickery, and wobbly?

I mean things like this:

|

|

What do I mean by oxidization?

I mean dark blobs like this:

|

|

Countless bootlegs were already circulating before David Shepard revealed this original print to the world.

That is why Number Six did not make it into many bootlegs.

It was too late onto the scene and the damage had already been done.

|

|

No longer can I remember every PD copy I saw on the rental racks or in the sale bins through the years.

I keep searching eBay and other online vendors and various search engines, too, in the hopes of jogging my memory,

and I’ve found some of the covers I remember having seen in the shops,

but by no means have I found them all.

When examining these video copies, it is clear that most are not direct copies of one of the above four sources.

No. They are copies of copies of copies of copies of copies of copies of copies of the above six sources.

Some of the PD dupes that I know about are:

|

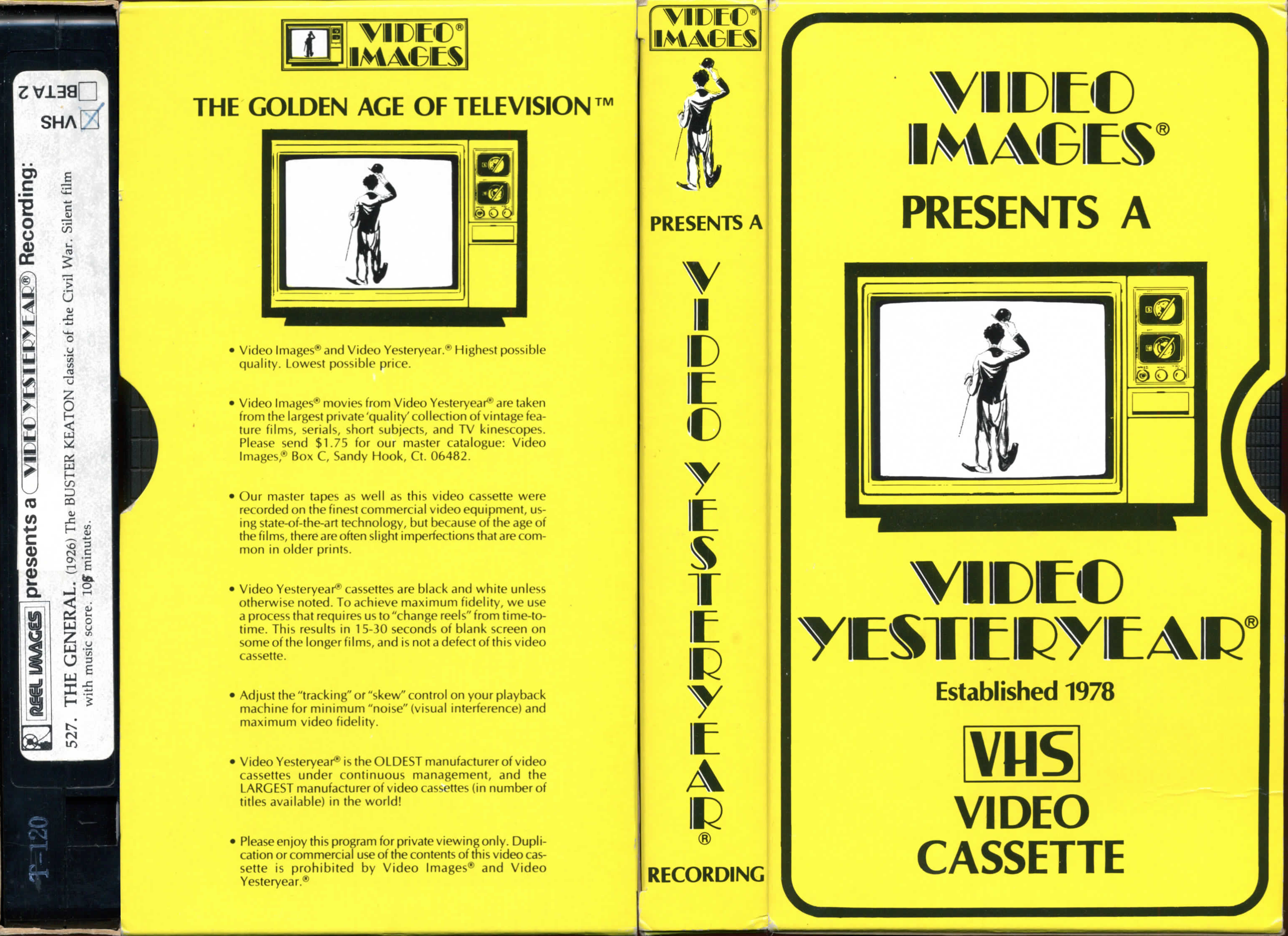

• Dupe of NUMBER THREE, the Glendale Alex preview print.

Dave Golden and Jonathan

“Jon” Sonneborn’s

Reel Images / Video Yesteryear

(February 1978).

You noticed above that Reel Images issued a 16mm edition.

Well, here we get to see what was on that 16mm edition.

This was a thousandth-generation dupe.

How? How on earth did anybody manage to dupe this?

We know for certain that Rohauer issued a 16mm print for nonprofit bookings as early as the mid-1960’s.

But that was cropped to the Academy sound format.

In 1972 he created a new edition that was optically reduced to the Academy sound format,

and apparently he also ran off at least one 16mm print.

My guess is that somebody at a nonprofit had a party late at night when nobody was looking.

As for this particular video, it was transferred through a prism at 16fps.

Slow motion. Wayyyyyyy too slow. Like everybody’s underwater.

The prism, a common device in flatbed editors, was here touted as the patented “Video Accu-Speed.”

I purchased a VHS recently (not in its original slipcase, alas), and, to my surprise, it utilizes a primitive version of Macrovision

that my Sima GoDVD stabilizer cannot bypass.

That tells me that my particular copy was not from the original 1978 production run,

but was made sometime between late April and mid-October 1984, when Macrovision was just learning to walk.

[When your Sima GoDVD stabilizer or off-brand equivalent is unable to bypass copyguard,

unplug it and patch in an RXII instead.

When the RXII messes up your image or inserts a black bar across the screen, unplug it and put back in your Sima.]

The middle of the film is flopped for some reason.

This is not the worst copy of the movie I have ever seen, but it is unwatchable and impossible to enjoy.

The reissue from late 1984 would be a different pass of the same print, with different music.

If you want to watch this video, right-click and save-as.

I am having an impossible time identifying these tunes,

and it doesn’t help that most are on piano rolls that added an infinitude of flourishes,

which served to disguise the underlying melodies.

Shazam helped with the E. Power Biggs pieces and Meade Lux Lewis.

An old buddy from the Buffalo area, who is steeped in the music of the 1920’s and 1930’s,

was able to help a little bit here, though this Tin Pan Alley stuff is not her area of expertise.

She was able to identify a few tunes, though.

I wonder which piano rolls these were — which company, which dates, which production numbers?

A musician friend assures me that these piano rolls were machine-cut, not hand-played,

and that would explain the horrid overuse of trills.

He concluded that these piano rolls

“sound like they are played on a badly maintained player piano with the sustain pedal stuck down

(and so may be from a tape provided by an amateur piano-roll enthusiast rather than a record album).”

Makes sense.

Sonneborn and/or his buddies at the editing board eliminated the pauses in between the pieces.

My musician friend was able to identify cues 16, 21, 22, 25, and 30. Hooray.

If you can identify more, please contact me. Thanks!

|

• Dupe of NUMBER ONE, the MoMA house print.

Allan Greenfield’s Video Dimensions (1981).

Horrible horrible horrible copy, millionth-generation 16mm dupe of the Harvard/MoMA edition.

This video has a maniacally relentless piano score by

Jon Mirsalis.

Jon has come a long way since them days.

|

• Dupe of NUMBER TWO, the MoMA circulating print.

Gerald A. Schiller, a well-known magician, created this compilation,

which included an 18-minute condensation of The General.

Schiller produced this through his company,

S-L Film Productions

(PO Box 41108, Los Ángeles CA 90041) in 1982.

It was in 16mm and it was sourced from public domain prints

that trace their ancestries back to MoMA’s 16mm circulating prints.

Red Buttons narrated.

Where this brief film was shown, I do not know, perhaps at schools.

In that same year, 1982,

Harmony Vision issued this on VHS, together with Schiller’s

1976 Chaplin documentary.

|

• Dupe of NUMBER THREE, the Glendale Alex preview print.

Dave Golden and

Jon Sonneborn’s Video Images /

Video Yesteryear (1984).

Visually similar to the 1978 release, the same print given a new pass through the flatbed.

Either it had no Macrovision or it had an improved Macrovision.

Once again, parts of the movie are flopped.

No more needle drops. This time it was scored by

Rosa Río

(1902–2010)

on a Hammond organ.

Lots of Casey Jones.

It was in the

summer of 1984 that Sonneborn hired Rosa Río,

and so it was sometime between June and December 1984 that her score was issued on VHS and βeta.

Ah, wait, here it is:

31 October 1984.

That was the day.

|

• Dupe of NUMBER TWO, the MoMA circulating print.

Jim Kartes’s

Kartes Video Film Classics

(1984).

My oh my, is this a mess.

Dreadful 16mm bootleg of the MoMA edition by way of Essex Film Club by way of Griggs-Moviedrome.

The cassette I have has an early version of Macrovision, which I am unable to bypass even with a Macrovision bypasser,

and so that would place this particular cassette not much after 24 April 1984.

The piano score is by Stuart Oderman.

What I think happened is that Stuart gave a live performance,

and Bob Lee recorded his performance.

Stuart is not given credit anywhere.

Then Bob Lee, or, more properly, Robert E. Lee (yes), added dreadful sound effects that make a terrible racket.

He wasn’t credited either.

|

• Dupe of NUMBER TWO, the MoMA circulating print.

Film Classics

(1985?),

same as the Kartes tape with its primitive version of Macrovision that I cannot bypass.

The only difference is that it’s at LP speed.

This was not copied from a Kartes VHS but from a Kartes master.

The generic slip cover and the generic label give not a hint about the date or distributor,

but there is a commercial at the end for The Official Video Journal’s Cinema Collector’s Society,

which is the same commercial shown at the end of the Kartes tape.

So, it seems that this generic Film Classics label is a bargain-basement edition from Kartes for members on a tight budget.

Perhaps this was sublicensed?

In my quest to place an accurate date on this tape, I am doing more online searches and finding peripheral information

that may but likely will not be of any use.

Jim Kartes began his video company in

1974.

By 1984, cardboard slip covers had become rather common.

The Official Video Journal was established on 19 January 1984

and application for its trademark was filed on

9 April 1984.

The trademark was canceled on 7 January 1992.

So, that places some boundaries around the date of issue of this VHS, but they are the same boundaries we would have had anyway.

Darn it!

If you know anything about this series of VHS cassettes,

please let me know. Thanks!

|

• Dupe of NUMBER TWO, the MoMA circulating print.

Kartes Video Film Classics (1985, reissue).

Scripps-Howard purchased Kartes in

late October or maybe the first of

November 1985

and gave The General a new clamshell cover, but not a new transfer.

Retains the early Macrovision.

|

|

• Dupe of NUMBER FOUR, Killiam’s 1970 edition.

Hollywood House Video (1985, Australia), the 1972 Thunderbird 16mm edition

with its soundtrack consisting entirely of 1930’s dance-band music, which flatly contradicts the movie.

The Thunderbird print, by the way, was a dupe of the Killiam print.

|

|

• Dupe of NUMBER FOUR, Killiam’s 1970 edition.

Prism Entertainment, Silver Screen Edition (1985, US),

exactly the same as the above Hollywood House Video.

|

|

• Dupe of NUMBER ONE, the MoMA house print.

Viking Video Classics (1986).

A dupe of Tarbox’s print, but with a gigantic gap that deletes the middle of the story.

This is run at 16fps, with no sound at all apart from VHS hiss.

|

• Dupe of NUMBER FOUR, Killiam’s 1970 edition.

All Video S.A. (Argentina, 1987).

The Thunderbird 16mm dupe with its dance music.

|

|

• Dupe of NUMBER TWO, the MoMA circulating print.

KVC (1988, reissue).

In 1988, Scripps-Howard sold Kartes Video Film Classics back to Jim Kartes,

who then renamed the company KVC.

This time The General was in a slipcase and either there was no Macrovision or there was a superior form of Macrovision.

As soon as Jim Kartes bought his company back, he sold it all over again, this time to Barr Entertainment, and he retired to Maui.

Barr added its sticker to the back cover.

|

|

• Dupe of NUMBER FOUR, Killiam’s 1970 edition.

Skema (Italy, 1988).

Unauthorized dupe of the Killiam/Perrry edition, in black-and-white.

Italian Chiron titles replace the English originals.

|

|

• Dupe of NUMBER FOUR, Killiam’s 1970 edition.

Filmax (Spain, 1990). This is Paul Killiam’s “Silent Years” edition

with Bill Perry’s score and with Karl Malkames’s 1971 tinting.

It is the same as the 1986 VHS issued by Channel 5 in the UK,

later issued in the US by Republic.

By the way, this is part of a 21-tape set:

You noticed that some of these are in the public domain,

some are part of The Rohauer Collection,

at least one is from Killiam Shows, and some are from MGM (now owned by Warner Bros.).

It would seem impossible to license all these for a single set.

|

|

• Dupe of NUMBER FOUR?

Altaya (Filmax Group) (Argentina, 1990). Most likely Killiam’s b&w edition with Perry’s piano.

|

|

• Dupe of NUMBER FOUR

Altaya (Filmax Group) (Argentina, ND). Certainly Killiam’s tinted “Silent Years” edition.

|

|

• Dupe of NUMBER FOUR

Altaya (Filmax Group) (Argentina, ND). Certainly Killiam’s tinted “Silent Years” edition.

Same UPC as the previous edition.

|

|

• Dupe of NUMBER FOUR?

Os Clássicos de Cinema / Altaya / Filmax (Brazil, 1990).

Most likely Killiam’s b&w edition with Perry’s score.

|

|

• Dupe of NUMBER FOUR?

Altaya (Ivex Group) (Spain, 1990).

Apparently Ivex took over Filmax, or the other way around.

This is Killiam’s black-and-white 16mm edition with Bill Perry’s piano track.

In English with Chiron subtitles.

There is no indication anywhere that this was licensed.

|

|

• Dupe of NUMBER ONE, the MoMA house print. Italian VHS.

The credentials seemed good: RCA, Columbia Pictures Video S.p.A., UniVideo.

What could go wrong?

Everything.

This is a grainy 20fps transfer of Charles Tarbox’s 16mm dupe of the Harvard/MoMA 35mm screening print.

No sound. I mean, no sound at all. Not a note of music. Not even analogue hiss. Nothing.

Oddly, the movie is entirely in English, without a hint of Italian anywhere.

Quality Control? Quality Control? Quality Control?

|

|

• Dupe of NUMBER ONE, the MoMA house print.

Intercultural Club Co., Ltd. / Polydor Co., Ltd., “Best Selection Series,” ICLS-1004

(1991), Japanese laserdisc, dreadful dupe of a dreadful ¾" U-Matic dupe

of Charles Tarbox’s dupe of the MoMA edition with the Harvard credit,

with anonymous accompaniment on a small home organ, essentially the same eight notes

over and over and over and over and over and over and over and over and

over and over and over and over and over and over and over and over and

over and over and over and over and over and over and over and over and

over and over and over and over and over and over and over and over and

over and over and over and over and over and over and over and over and

over and over and over and over and over and over and over and over and

over and over and over and over and over and over and over and over and

over and over and over and over and over and over and over and over.

|

• Dupe of NUMBER ONE, the MoMA house print.

Mykkäfilmi M/V (1992, Finland).

The 107 minutes would indicate that it was transferred at 16fps.

I know what this is.

Here.

This is Charles Tarbox’s 16mm print, slowed down to 16fps,

with inappropriate music, beginning with Elgar’s “Pomp and Circumstance.”

Jeff Aikman had started JEF Films in 1974 when he was 13,

just as Charles Tarbox had started Film Classic Exchange when he was 13.

As he was dying, Charles told his wife to sell his Film Classic Exchange materials to Jeff.

That was at the end of 1984.

In August 1992, Jeff founded a new company, Aikman Archive, to issue this new collection on VHS.

Before the end of 1992, he released this edition of The General in the UK, and he claimed copyright to the film.

This is in slow motion with inappropriate needle drops.

More on the music a little below.

|

• Dupe of NUMBER THREE, the Glendale Alex preview print.

Mastertronic (Spain, 1994, though an

online source says 1990;

perhaps Mastertronic issued this twice?).

Rather nice dupe of the 1987 Thames Silents edition, which was transferred directly from the 12 November 1926 preview print

shown at the Alexander Theatre in Glendale, California.

In this Mastertronic video, most of the titles are replaced by Spanish translations.

The Carl Davis score is deleted and in its place is an uncredited piano score that is pleasant enough but not appropriate to the film.

|

• Dupe of NUMBER ONE, the MoMA house print.

Allied Artists (1995). Dupe of Tarbox’s print, slowed down to 20fps, about 95 min.,

no music, no sound at all, not even VHS hiss.

A customer named “L Day” posted a bizarre review of the DVD edition of this video on

Amazon:

|

★☆☆☆☆ The General Allied Artists DVD

Reviewed in the United States on August 4, 2012

Verified Purchase

This review is specific to the of Buster Keaton’s the General produced by Allied Artists version,

the one found in the Buster Keaton Collection by St Clair vision, and those by Kino.

I won’t bother to discuss the story, others do an incredibly good job of that,

this review is limited to technical issues.

Finding a full length copy of the General can be a serious problem for a silent film aficionado.

I have long regarded this as the best silent movie and wanted a perfect copy of the original full length film at 105 minutes long,

unfortunately every quality copy I could find is an abridged 75 – 78 minutes long.

Some people have attempted to explain the difference in speed as the cameraman’s decision to run the reels faster or slower,

but quite frankly a speed differential of 40% due the enthusiasm of the cameraman was a little hard to believe.

I later did a side by side comparison and found over 200 differences where I could find cuts in footage.

The movie seems to have either been cut differently for American and International audiences or the surviving 35mm version

was abridged for televised broadcast when they first started playing silent movies on the tube.

I have been able to discover that the 105min version was preserved on a 16mm reel found in either Australia or New Zealand,

this 98 minute Allied Artists version comes from a Spanish 16mm reel;

and the 75 minute versions by Kino and others come from the remaining 35mm reels found in the States.

It would be nice to know what theater audiences originally saw in the U.S. but information from the era is sketchy

and best guess is that they watched the short version.

I have found writings which claim that American audiences of the 1920’s preferred movies to be around 70 minutes long

while International audiences preferred longer films.

One thing which influences the review, I have a personal preference for original organ scores

because the original artists tended to understand the importance of music to a movie and gave it a lot of thought,

music is key to setting the mood and tone of any silent movie.

The Allied Artists version of the General rated one star because there is no sound track.

Someone at Allied needed to pay more attention to production details.

I could live with the movie originating from a 16mm pressing

since the full version of the movie is not available in a high quality print, considering the origins it is clean.

When it comes to sound; however, the case clearly states “dolby stereo”,

which is a near universal format and there is no sound track whatsoever.

I ran some rather sophisticated anaylsis on the disc

to make sure I didn’t have an equipment compatibility issue — and it just isn’t there.

This is an unforgivable lapse, and more than a little deceptive.

Others on the net have made this observation as well so I don’t believe the problem is limited to my disc.

Face it, Dolby Stereo silence is not a big draw when purchasing a silent movie.

The Buster Keaton Collection by St Clair Vision contains a lesser version of the full 105 minute movie

and would also rate one star but for different reason.

They appeared to have a random classical music soundtrack.

How they thought Elgar’s “Pomp and Circumstance” (most know it as graduation music)

could be be applied to an American war movie is beyond me.

Its use is sloppy and indicates a lack of thought.

The music is jarring and ruins this most worthy of films.

Again you wind up watching the film truly “Silent”.

So I am still left watching the short but visually and symphonically perfect Kino pressings.

Most of the Kino Releases are perfect and this one is no different.

Kino provides multiple musical scores depending on ones taste and they offer the best visuals available.

I gave them four stars because I wish they would produce a full length version of the General,

but otherwise there is little I can say that would result in a better product.

Lastly, the film is based on a book written around 1898 by Lieut. William Pittenger

“Daring and Suffering: A History of the Great Railway Adventure (aka The Great Locomotive Chase)”

a fictionalized account of the Andrews Raiders attempted sabotage of the Confederate Railway System.

Historically this raid was itself a fascinating story. I have never seen a copy of the book.

|

Over 200 differences consisting of cuts in the footage????????

It’s a dupe of the Harvard/MoMA print,

which was taken from the United Artists camera negative.

Not a frame is different.

As usual, people do not see what’s plainly before their eyes;

they see what they think they see, what they are told they’re seeing.

(I’m as guilty as anybody, of course.)

|

• Dupe of SOMETHING.

MM&V Marathon Music & Video (1995).

This is Volume III of a seven-tape box set.

Apparently this was a 16fps transfer,

most likely the Aikman horror.

For what it may be worth, here is what the box set looked like:

From what I understand, each of these seven films was presented in the worst way possible,

each with a musical accompaniment that was less than unremarkable.

|

|

• Dupe of NUMBER FOUR?

Filmax (Spain, 1995). Most likely a new production run of Killiam’s tinted “Silent Years” presentation.

|

• Dupe of SOMETHING.

Cine Clasico (Spain, 1996). No clue what this is.

The tape cover is a metal can.

Now, color me ignorant, but in my experience, magnetic tapes tend not to be happy about being stuck inside metal cans.

|

|

• Dupe of NUMBER FOUR, Killiam’s 1970 edition.

Pentrex (1997). The Thunderbird edition,

identical to the 1985 Hollywood House,

identical to the 1985 Prism,

identical to the 1991 Pearl.

Hmmmmm. Prism, Pearl, Pentrex.

Were those three companies related?

|

• Dupe of NUMBER ONE, the MoMA house print.

JEF Films International/Aikman Archive (14 May 1998).

This is yet another release of Jeff Aikman’s edition,

which was Charles Tarbox’s dupe of the Harvard/MoMA print slowed down to 16fps

and paired with inappropriate needle drops.

Take a look – if you dare.

The distributor, Morningstar Entertainment, had the gall to open the tape with an Interpol warning.

As for the music, I got curious.

Shazam identified all but the final piece, which SoundHound identified.

|

|

Barry Tuckwell conducting the London Symphony Orchestra in Elgar’s “Pomp and Circumstance.”

Leopold Hager conducting the Radio Luxembourg Symphony in Strauss’s “Pizzicato Polka.”

Rafael Frühbeck de Burgos conducting the London Symphony Orchestra in Bizet’s “Danse bohème” from “Carmen.”

Leopold Hager conducting the Berlin Symphony Orchestra in Tchaikovsky’s “Marche Slave.”

Yuri Ahronovich conducting the London Symphony Orchestra in Khachaturian’s “Sabre Dance” from “Gayane.”

Barry Wilde conducting The Serenata of London in Grieg’s “Sarabande” from the “Holberg Suite.”

Leopold Hager conducting the Radio Luxembourg Symphony in Strauss’s “Radetzky March.”

Yuri Ahronovich conducting the London Symphony Orchestra in Borodin’s “Polovtsian Dances” from “Prince Igor.”

Ole Schmidt conducting the Royal Philharmonic Orchestra in Borodin’s “Polovtsian Dances” from “Prince Igor.”

Yuri Ahronovich (again) conducting the London Symphony Orchestra in Borodin’s “Polovtsian Dances” from “Prince Igor.”

The Vienna Philharmonic plays Strauss’s “Tales from the Vienna Woods.”

Jascha Horenstein conducting the Orchestra of the Vienna State Opera in Strauss’s “Tales from the Vienna Woods.”

The Vienna Philharmonic plays Strauss’s “The Voices of Spring Waltz.”

Orquestra de Cordas de Viena plays Strauss’s “Roses from the South.”

Wiener Volksopernorchester plays Strauss’s “Wiener Blut.”

Robert Stolz conducting the Vienna Symphony in Strauss’s “On the Beautiful Blue Danube.”

The Lifestyle Orchestra plays Strauss’s “Wine Women and Song.”

The Vienna Philharmonic plays Strauss’s “Morning Papers Waltz.”

Robert Stolz conducting Strauss’s “Künstlerleben.”

The Vienna Philharmonic plays Strauss’s “The Artist’s Life Waltz.”

The Wiener Volksopernorchester plays Strauss’s “Kaiserwalzer.”

Anton Paulik conducts the Vienna Symphony in Strauss’s “Kaiserwalzer.”

The Wiener Volksopernorchester (again) plays Strauss’s “Kaiserwalzer.”

Anton Paulik conducts the Vienna Symphony in Strauss’s “Wiener Blut.”

The Emerson String Quartet plays Claude Debussy’s “String Quartet No. 1 in G Minor.”

|

|

And then when the movie ends, the music just abruptly cuts off in the middle.

No music credits.

|

|

• Dupe of NUMBER THREE, the Glendale Alex preview print.

Non Fiction Video (1999).

Dupe of the 1984 Video Yesteryear tape with Rosa Río’s organ score.

|

|

• Dupe of NUMBER THREE, the Glendale Alex preview print.

Bettlach Société Limitée/CNC (circa 1999???).

Unauthorized dupe of the 1987 Thames/Brownlow/Gill/Davis tape.

French captions underneath the English titles.

From a Swiss company called Bettlach S.L.,

which seems to have been owned by Claude Berri and Jean-François Davy,

and it seems that the videocassettes were licensed to a French government agency,

CNC (Centre National du Cinéma et de l’Image Animée).

There is no date anywhere.

|

|

• Dupe of NUMBER THREE, the Glendale Alex preview print.

Pickwick France (France, 1993).

Unauthorized dupe of the 1987 Thames/Brownlow/Gill/Davis tape.

French Chiron titles replace the English originals.

The cover illustration gave me some hope that the tape would derive from the 1962 French reissue from Athos Films.

Nope. Nope. Nope. Nope. Nope.

It was just a random illustration pulled out from wherever they found it,

and they plopped it onto the cover without authorization.

Typical. Predictable.

|

|

• Dupe of SOMETHING.

Raul Rocha’s Century Video Locaçao & Comercio Ltda. (Brazil).

No clue what this is.

|

|

• Dupe of SOMETHING.

Cine Horizon (France). No clue what this is.

|

|

• Dupe of SOMETHING.

Circulo Cultural del Cine (Argentina). No clue.

|

|

• Dupe of SOMETHING.

Clasicos del Cine Comico (Spain). No clue.

|

|

• Dupe of SOMETHING.

Comicos de Hollywood (Argentina). No clue.

|

|

• Dupe of SOMETHING.

Joyas del Cine Comico (Argentina). No clue.

|

|

• Dupe of SOMETHING.

Panda Film (France). No clue.

|

• Dupe of NUMBER ONE, the MoMA house print.

Eureka, yes, offered Aikman’s edition, 16fps, which came out in

2001 (not 2006!).

|

|

• Dupe of NUMBER ONE, the MoMA house print.

The Tallahassee Film Society offered a VHS dupe of the Aikman edition,

the same as the Eureka VHS above.

Hardshell case, with a card-stock insert printed on a home laserjet.

There is no date anywhere, but I would peg this as sometime around 2004.

|

• Dupe of NUMBER ONE, the MoMA house print.

Pickwick Group Limited, Elstree Hill Entertainment (2004, UK),

PAL Region 0, which may or may not play on US equipment.

This is a dupe of Aikman’s VHS, slowed down to 16fps,

with a Joplin tune at the beginning.

It was not flattering to Scott Joplin or to Buster Keaton.

After about two minutes I ejected the disc and put it on my shelf.

Then, just now, it dawned on me:

I know what this is!

There was an article titled

“‘The General’ Saluted with New Soundtrack,” in

The Morning Call of Sunday, 24 December 1995:

|

...A Bucks County millwright has commissioned and edited a score of Scott Joplin piano rags for the 1927 silent movie “The General”....

What separates Eric Grob’s production, which will air at noon Friday on WLVT-TV, Channel 39,

from recent reconstructions of Keaton film scores is that he’s an amateur....

For years he’d admired silent comedies starring the likes of Mack Sennett and Fatty Arbuckle;

for years he’d admired the music of LeRoy Shield,

who scored Hal Roach-produced talkies featuring Laurel and Hardy and the Little Rascals

(yes, Shield wrote the Rascals’ merry-go-round theme).

One day Grob experimented with Shield’s music as a rough soundtrack to “The General.”

He enjoyed watching Keaton’s frozen-faced Southern worm steal back a train and a girlfriend swiped by Yankees,

using a bicycle and a locomotive, ingenuity and dumb luck.

What he didn’t like were Gaylord Carter’s piano variations on “Dixie,”

“I’ve Been Working on the Railroad” and other folk ditties.

The score was so irritating, he took to switching it off.

While reviewing the match between Shield and Keaton, Grob happened to remember

a recent comparison between the composing styles of Shield and Joplin.

On a whim he put a Joshua Rifkin recording of Joplin’s “Ragtime Dance” on the phonograph

and turned off the sound to the opening moments of “The General.”

His jaw plummeted with shock.

There, in Joplin’s strolling left hand, was the sound of Keaton’s stately pathos.

There, in Joplin’s cakewalking right hand, was Keaton’s pistoning jauntiness.

Changing “The General” for commercial use wasn’t a problem.

The film had been public domain since 1988, or 50 years after the death of copyright holder, movie mogul and Keaton boss Joseph Schenck....

He acquired a vintage 1972 reel-to-reel tape recorder and a video enhancer.

In his living room, armed with two VCRs, a monitor and a stopwatch, he matched scenes to 18 Joplin compositions.

To record them he hired Charles deMets, a Norristown jazz pianist and ragtime buff who’s touring in the ballet “Beauty and the Beast.”

Grob, 43, believes he’s doing more than enlivening “The General.”...

This year Kino Video, as part of a 30-film centennial package, released “The General” with an organ score.

Last month “CBS Sunday Morning” mentioned the Library of Congress’ restoration of the first soundtracks of Keaton’s pictures....

Grob’s next project is to transfer the Joplin soundtrack to a “General” print

that’s cleaner and ready for theatrical projection.

To learn the 16mm format, he’s enrolled in a community-college course.

A longer-term goal is to score Keaton’s two-reelers with Shield’s music.

To do that, he’ll have to get the permission of the copyright holder, who happens to be the composer’s stepson,

and Koch International, which this year issued two CDs of Shield’s works....

To order the Scott Joplin-scored “The General,”

send a check or money order for $24.95 (plus $1.50 sales tax for Pennsylvania residents) to:

Eye American Productions Inc., P.O. Box 193, Pipersville, Pa. 18947.

|

My heavens! That article was littered with errors, top to bottom.

Anyway, it got me interested, and I began to search high and low for Grob’s DVD,

which seemed to have vanished from the planet.

Then, like I say, it finally dawned on me that I had a copy all along! The Elstree DVD!

The opening piece is Joplin’s

“Fig Leaf Rag,”

a great tune, yes, but wrong for this movie.

Now I have it playing all the way through.

The music does not fit at all, and it was not edited to match the scenes.

It is just one Joplin piece after another, pasted onto a bootleg run in slow motion.

The locomotive crashing through the burning bridge, though, what music was on that?

None.

Just the rumbling of the turntable as Grob switched from one record to another.

Some of the pieces are from Joshua Rifkin’s solo album, Scott Joplin: Piano Rags

(Nonesuch Records, November 1970);

the others, I don’t know.

|

| 0:00:00 |

Fig Leaf Rag |

| 0:04:40 |

Scott Joplin’s New Rag (Rifkin) |

| 0:07:51 |

Euphonic Sounds — A Synchopated Novelty (Rifkin) |

| 0:11:49 |

Magnetic Rag |

| 0:17:05 |

Original Rag |

| 0:22:01 |

Weeping Willow — A Ragtime Two-Step (Rifkin) |

| 0:26:26 |

The Cascades Rag |

| 0:29:35 |

The Chrysanthemum |

| 0:34:34 |

Sugar Cane |

| 0:37:42 |

The Nonpareil |

| 0:41:47 |

Country Club — Ragtime Two-Step (Rifkin) |

| 0:46:44 |

Maple Leaf Rag (Rifkin) |

| 0:49:30 |

The Entertainer — Ragtime Two-Step (Rifkin) |

| 0:54:33 |

The Ragtime Dance (Rifkin) (cuts off abruptly) |

| 0:57:00 |

Fig Leaf Rag |

| 1:01:39 |

New Rag (Rifkin) |

| 1:04:51 |

Euphonic Sounds — A Synchopated Novelty (Rifkin) |

| 1:08:49 |

Magnetic Rag |

| 1:14:05 |

Original Rag |

| 1:19:01 |

Weeping Willow — A Ragtime Two-Step (Rifkin) |

| 1:23:26 |

The Cascades Rag |

| 1:26:35 |

The Chrysanthemum |

| 1:31:34 |

Sugar Cane |

| 1:34:32 |

The Nonpareil |

| 1:38:47 |

Country Club — Ragtime Two-Step (Rifkin) |

| 1:43:44 |

Maple Leaf Rag (Rifkin) (cuts off abruptly) |

|

• Dupe of NUMBER THREE, the Glendale Alex preview print.

Coupé Entertainment (2004, Spain),

PAL All-Region, which may or may not play on US equipment.

Oh, this one got my hopes so high, and then deliberately dashed my hopes against the rocks.

The front cover shows the 1962 Spanish poster. Hmmmmm.

The back cover assures us that the music is by Konrad Elfers. Hmmmmmm.

Could it be? Could it be? Could it be?

Of course not!

This is an unauthorized dupe of the Image Entertainment laserdisc ID6862HB of 1989.

Well, should I have expected truth in advertising?

|

|

• Dupe of “THE ART OF BUSTER KEATON,”

which in turn was taken from NUMBER THREE and NUMBER SIX.

Issued by Ermitage Cinema, Gruppo Editoriale L’Espresso S.p.A. (2010, Italy),

PAL DVD, I think it’s all-region, but I’m not sure.

The piano that plays while the movie is running is a piano that plays while the movie is running.

There is no relation between the music and the image.

There was no licensing agreement between Ermitage/L’Espresso and David Shepard’s Film Preservation Associates, either.

|

• Dupe of NUMBERS ONE AND FOUR, the MoMA house print and Killiam’s 1970 edition.

This is the Cottage Grove Historical Society’s 16mm dupe composite.

Some Busterphiles seem to enjoy

Mark Orton’s score.

I think it would be okay as a stand-alone concert piece.

Not my type of music at all, but that’s neither here nor there.

I don’t know why on earth this music was glued to the movie.

Whatever.

I doubt that this edition would win over even a single new convert.

Apparently there was a second pressing, this time from a superior print.

I haven’t seen that, but I’d be most interested in looking at it.

|

And there were others besides, plenty of others.

I saw some snippets ages ago,

but I can’t remember which was which and what was what, except to recall that they were all horrible.

WorldCat tells me that a few other VHS distributors were

Grapevine Video (Phoenix, Arizona),

CEL Entertainment (St. Leonards, NSW),

Jasonfilm (Springwood, NSW, 1987, licensed from Essex),

Spectrum (England, 1980),

Discount Video Tapes (Burbank),

Budget Video (Los Ángeles),

Cable Films (PO. Box 7171, Country Club Station, Kansas City, MO 64113),

Virgin Vision Australia (Richmond, VIC).

There were others. I know there were others, but, blast it all, I can’t quite remember what they were.

They are almost within my memory’s reach, but I can’t picture them, I can’t dredge them up.

Darn it!

I’d recognize them if I could see them again.

|

As for the plenty of others besides, I remember circa 1995 when one of the two local Buffalo PBS stations scheduled The General.

Ah. Here it is.

WNEQ Channel 23, Tuesday, 27 September 1994, 8:00pm.

Hoping that it would be a good quad of a good edition pulled from a transmission from PBS HQ, I tuned in and pressed RECORD.

Alas, when the show started, I saw that Channel 23 was merely broadcasting a public-domain dupe of the MoMA edition, from a common VHS.

It was from Kartes.

It opened with the standard home-use-only-not-for-public-performance-or-broadcast warning,

but the Kartes tapes in my collection do not open with such a warning.

I would not be at all surprised if one of the station’s staffers just rented it from the local

Video Factory.

I let the tape record for maybe two or three minutes and then I gave up.

I still have that tape somewhere in storage, unmarked, and I’ll probably never be able to find it again.

|

Is that a memory test, ’r what?

|

Of the PD dupes, I’ve watched only the Eureka all the way through,

and I watched much but not all of the noisy Kartes edition with all its rumbling and scraping and grinding.

As for the others, my stomach cannot handle the distress.

I watch a little bit and that’s about all I can take.

Suffice it to say that they are all bloody awful.

Anyone who would have the misfortune to be introduced to the movie with any of these video editions would despise it.

Silent movies need good prints, properly projected onto large screens in genuine movie palaces, with large audiences,

with sensitive live musical accompaniment.

Silent movies are tremendously diminished when seen on video, even the best videos from the best prints with the best music.

When silent movies are put on video with lousy or inappropriate music, poorly projected,

shown in smeary and flickery and washed-out prints,

there is nothing left to enjoy.

They are not living, breathing performances; they are just a couple of bones robbed from a grave.

The VHS issues of PD dupes should never have been offered.

They ruined the film’s reputation and they surely drove lots of people away forever.

Now there are

multitudes of DVD dupe editions, the majority of which should never have been released.

Any attempt to catalogue all these atrocities from cheapo distributors would lead to clinical depression.

Nonetheless, I am now on a mission to document every last VHS release.

Heaven help me.

|

|

A snippet from an interview.

I’m okay with Mel Brooks saying that he didn’t find The General funny

or that it wasn’t his cup of tea. Fine.

But “dreadful”?

What went wrong?

At Eleanor’s house, he and Don Rickles saw a 16mm Killiam print.

If you know Mel, could you hand him the Kino K669 Blu-ray from 2009,

select the Carl Davis score, and force him to watch it?

He won’t regret it, I assure you.

|

Now, let’s look at some comments posted online.

Some people just don’t care for Buster, and that’s fine.

I have met and worked for narcissists, violent maniacs, psychopaths, and a murderer/arsonist

who either didn’t care for Buster or who simply had no taste for any of the finer things in life

and who would surely not have been receptive to Buster.

I’m glad they’re not receptive to Buster.

I wouldn’t want them to be.

When your great goal of the moment is scoring a drug deal while keeping ahead of the cops,

you’re just simply not going to be enchanted by a painting by Monet or a tune by Grieg or a movie by Buster.

Ain’t gonna happen.

Similarly, there are those like my uncle

and various others who simply do not have any sense of humor at all,

or any sense of beauty or any sense of wonder or any sense of anything, really.

There are also plentiful people, and I have met too many of them, who are incapable of distinguishing beauty from ugliness.

They literally cannot tell if something is beautiful or ugly, they don’t understand the meaning of the words,

and when people discuss the matter, they get confused.

There are also those people, who constitute the vast majority of people on this planet, who are not receptive to ANYTHING that is unfamiliar,

and they unknowingly follow the dictates of marketing executives who are in total control of deeming for us what is familiar.

Further, there are those who are not moved in any way by The Red Balloon and who cannot understand why anybody would like it.

Fine.

Then there are those who see Buster as emotionless and hence unrelatable.

Those are the people who, I assume, were born with incomplete emotions.

(There are those who have said the same about me, that I am just an emotionless machine.

I hear that and I look at them and I look at their faces and I realize, hey, they just don’t get it.

They can’t perceive what’s plainly in front of their eyes.

I cannot even fathom how they experience life, and I don’t want to.)

But then there are others who should probably like Buster and who should probably like The General but who don’t.

I wonder what they saw when they thought they saw The General.

Did they see Killiam’s “Hour of Silents” edition?

Did they see the Kartes VHS?

Did they see the Allied Artists VHS?

Did they see the Video Yesteryear VHS?

Did they see the JEF Films/Aikman Archive VHS?

Did they seem some cheapo bargain-bin DVD edition from a hundredth-generation dupe with a needle-drop music score?

Did they see something even worse?

Did they, horror of horrors, attend a showing that was accompanied by a

rock

band

or by noisemakers?

Or was the screen blowing in the wind?

Of course, anybody introduced to the movie through one of those wretched atrocities would dislike the film.

Those horrid editions remove all the beauty, all the dignity, all the humor, all the finesse, all the nuance of Buster’s original

and replace it with cacophony and/or wisecracking narration and/or ruined images.

Those editions are so far removed from what Buster made that they cannot be considered his.

They are not The General. They are defamatory counterfeits.

Opinions:

|

|

I’m watching this in 2021 so I’m more than aware my review isn’t fair

but it just didn’t hold up for me.

I’m sure this is the best that silent movies have to offer,

I was just ready to have it end and it’s only an hour movie.

I’m about 100 years late though so I get why it’s rated highly and why it’s well thought of.

They did the best with what they could and Keaton is a well loved movie star.

|

|

I have watched The General twice and my opinion of it has remained virtually unchanged.

I find that it simply isn’t all that funny, and overall not very engaging.

Oddly, the funniest scenes are the ones involving the actress Marion Mack,

like when she throws away a piece of firewood because it has a hole in it.

I’m aware that many regard this movie highly,

and I honestly wish I enjoyed it more. But its really quite drab.

|

|

Some critics feel they’ve a Midas touch, turning to gold all they gild,

but in fact, may just be spinning straw for the Studios.

Buster was a comedy pioneer and stunt specialist, yet, despite modern attempts to lionize this film,

not without its great aspects in staging scenes, did err in trying to turn Civil War oddity (train trade-offs) into laughs.

What is curious is that one of his players, former Giants great Mike Donlin (US General),

erred in similar fashion, leaving MLB (.333) for an acting career where he hit around .200 (bit parts).

The lesson: Stick to what you know.

For Keaton, that was all his terrific rom-com shorts made in years prior,

ones that fit his form like silks a Jockey® (2/4).

|

wumbi, 11 January 2022

Dated

I appreciate the craft that goes into making it but that wasn’t funny in any way shape of form.

The jokes are outdated and I can’t even begin to think how anyone could look at that and be like wow that was funny.

|

|

I saw this film as a result of trolling through the listings here at imdb looking for a great film I hadn’t seen.

I looked at 3 or 4 video stores before I found a copy to rent, brought it home, and, boy, was I disappointed.

The film’s OK, and I’m sure it was quite a spectacle for 1927,

but part of the problem is that it’s just too far back in time.

It’s probably worth viewing once just for the historical value of seeing an old silent movie,

and if you looooooower your expectations you may really enjoy it; but for me, once is definitely all I could take.

|

|

What did those people really see?

I assume they all saw some bastardization that was still called The General but that was really no longer The General.

|

COLOR.

One more thing I guess I should mention.

If you browse around YouTube, you will find various attempts at adding sound effects and color to The General.

I have very mixed feelings about this.

Yes, I enjoy witnessing the experiments,

not only with but The General but with all manner of films of the 1920’s and prior.

Chaplin’s Keystones especially have an entirely different feel with colors added.

I just love good black and white, provided it’s properly shot and processed and printed,

and I love sensitive, appropriate music accompanying, especially live, especially by ensembles and orchestras.

Color and sound effects are unnecessary and take away at least as much as they add.

Yet I really like Jay Ward’s edition, more for the vintage mood music than for the sound effects,

though the sound effects, oddly enough, don’t bother me in the least.

Another attempt I really like is this colorized YouTube video,

which uses the Cohen restoration and the Davis score without authorization:

Full movie: The General (1926) ft Buster Keaton [Colorized 50fps 4k],

posted by Smiling Solstice Memories

on 27 November 2020.

I do not prefer this over the original, but it does give me a different perspective on the movie.

Despite our æsthetic objections, despite our queasiness about the purloining of copyrighted work that is still, today,

in print and on the market and easily available at a reasonable price, you may just find yourselves enjoying this.

|

|

Lobster Films has one of the several copyright claims on this British DVD set:

|

|

This is quite good, and I could not understand why it was so good.

At long last, I have a clue.

This was taken from a copy negative that was missing all the titles, and that also had a 22-frame gap in Reel 5.

Does that sound familiar, ’r what?

I had suspected that when Jay Ward’s crew made a copy negative from the fine-grain,

they made more than one.

They made one for themselves and another for Rohauer.

Then I thought, no, I bet they made more than one for themselves.

I bet they made a full-aperture copy neg as well as an Academy reduction copy neg.

Yes?

I bet they made even more than that, as protection.

The titles from at least one of those copy negs would definitely have been deleted in the process of creating the 1970 reissue,

which, as you will recall, had no titles at all.

Well, that seems to explain it:

One of those copy negatives ended up with Lobster Films.

What to do about the missing titles?

Why, pull them in from an original nitrate release print, of course!

What original nitrate release print?

It was David Shepard’s print, which I am nearly certain had previously been Buck Manbeck’s print.

Yes? Makes sense?

One of the DVD supplements is called “The General Restored,” all too short at a mere two minutes.

It shows the damage printed in to the copies currently available,

and it also shows some shrinkage.

Whether that damage and that shrinkage were on the copy neg or on some other prints, I do not know.

The DVD supplement also makes clear that those defects were digitally corrected in preparation for this DVD release.

What’s more, it also showed a print slowly moving through a scanner frame by frame.

That image made my blood run cold. Take a look:

|

|

Duplicated framelines, and, hey, look at the left side of that piece of film.

There is a soundtrack that obliterates the left side of the image!!!!!

This was the Athos Films release from June 1962,

the French translation of the February 1962 Atlas Filmverleih release,

and it was printed in Munich at Beta Technik.

Rohauer’s 1963 festival print was full-aperture.

The 1970 Killiam print was full-aperture.

The 1970 Jay Ward version was an optical reduction.

Rohauer’s 1972 touring print and 1979 release prints were optical reductions.

|

|

Let’s try something.

The film as seen on the scanner is deceptive, because light is bouncing all around that machine and is shining through the film,

which makes finding the same frame on the video version a bit tricky.

But I found it.

So, if I tilt and redimension the film image (not perfectly, sorry)

and put it right above the full frame:

|

The movie on this DVD set included the entire frame, heavens be praised,

and so we can wonder why the lab went to the trouble to make a scan of a print that was missing about 10% of the image.

I just learned why.

This was a re-enactment.

When it came time to make this little video, the staff just grabbed any old print of The General off the shelf

and plopped it onto the scanner just to get an image of a print moving through the scanner.

This print was not scanned; it was not used in the restoration.

What if this was not an Athos print, though?

If not, then what could it have been?

Was this perchance the Jacques Robert/Capital Films-Etoile Distribution edition from circa 1970?

Was this perchance the

Galba-Films Distribution, S.A., edition from 1974?

Oh. I know what it is.

This is the 1962 French release from Athos with the Konrad Elfers score,

printed by Beta Technik in Munich.

|

Poster for the Galba-Films reissue from 1974.

Image stolen from nememka’s eBay listing.

I have yet to find any material on the Capital Films reissue from circa 1970.

|

|

By the by, in the fruitless, futile (“fruitile” as a friend once put it) effort to learn more about the French releases,

I just ordered from eBay Cinéma no. 155 from February 1975,

a special issue devoted mostly to Le mécano de la « General ».

Yes, the English spelling was retained for “General,”

and that makes me suspect that this issue used as its primary source the Galba-Films edition of 1974,

but I cannot be certain about that.

The magazine, disappointingly, tells us nothing about the various releases.

It pulled info from all sorts of erroneous sources about release dates

as well as the obviously unresearched

“Musique et bruittage (réalisée après 1928) KONRAD ELFERS.”

Oh well.

It includes a complete transcript of a French print of the film,

a print mounted onto 2,000' reels, but which French print?

It was definitely not the 1927 edition from Les Artistes Associés.

It was definitely not the 1962 edition from Athos Films.

It may or may not have been the circa-1970 edition from Capital Films.

I would guess it was mostly likely the 1974 edition from Galba-Films.

Whatever this print was, Johnnie became Johnny and Annabelle became Mary.

Why would anybody have made such pointless changes?

My best guess is that Galba asked Rohauer for a contract to release the film,

but did not ask for any preprint materials, because Galba already had such from another source.

Well, that other source had a very defective edition!

Is my guess correct?

No, it isn’t.

Galba was Friedman’s company.

What source was used for the Galba edition, and why, remains a mystery.

|

|

The transcript reveals, horrifyingly, that the edition of the film under review was missing the following titles:

|

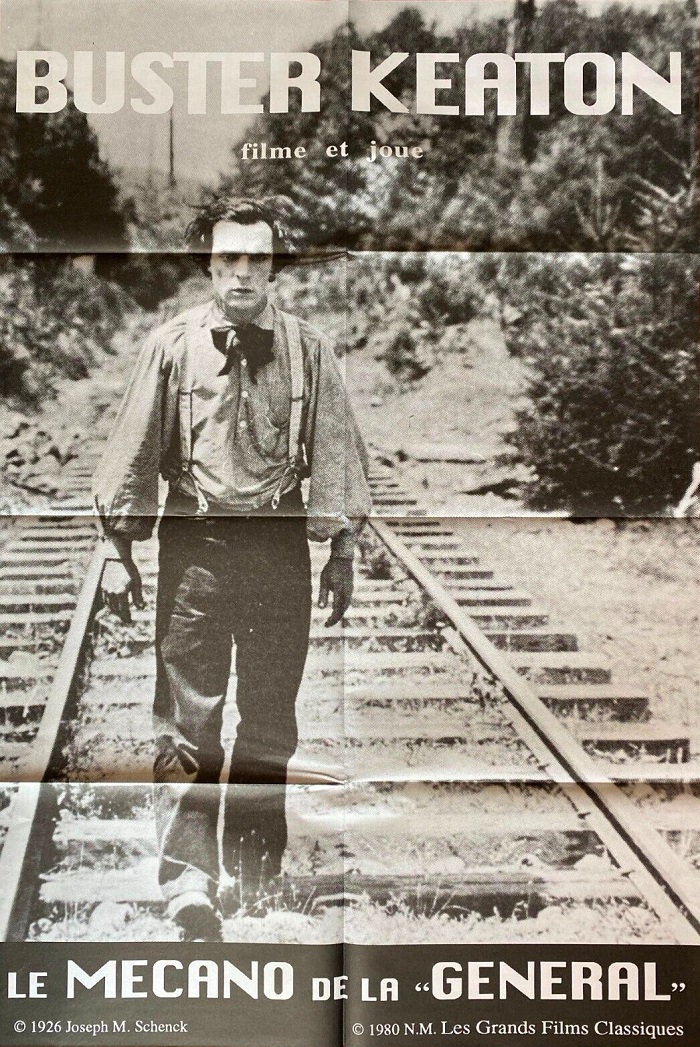

Oh. Just now I discover that there was another reissue from a firm called

Les Grands Films Classiques,

which has been in business at least as far back as

1950.

I see that this reissue Le mécano de la « General » (again with the English spelling) is from 1980.

I understand that the music was by

Hubert Rostaing, I presume just a bunch of old recordings spliced together.

But who knows? Maybe it was an original score?

The poster is below:

|

K27-90

|

|

Four reissues, all of them mysterious.

These are the questions that cause me to lose sleep.

|

|

|