Back to The General |

|

So much for Sherlock Jr.

Now let’s get back to The General.

Rohauer by now had mutilated most of the Buster releases,

and so now he chose to claim production credit on an altered edition of The General.

|

|

Here is a collector who enjoyed the Jay Ward “sound version”:

|

|

“Fractured Flickers,”

The Classic Horror Film Board, comment by Ryan Brennan, 15 July 2017:

“Jay Ward and Bill Scott might have had some real affection for silent films. Perhaps as a result of the work entailed in finding suitable clips for the show they must have run across a lot of Buster Keaton material. This resulted in a new sound version of Keaton’s THE GENERAL. A new score was commissioned, some sound effects added, and the |

|

The crazy thing? I’m really beginning to enjoy the Jay Ward edition, too!

|

|

Skip Craig’s description of

The Golden Age of Buster Keaton is a bit of a revelation.

A college buddy saw it on HBO and he told me that it was a documentary with lots of clips.

I would love to see it, but it has never been shown since.

Does it still exist? I don’t know.

According to Skip,

The Golden Age of Buster Keaton that my friend saw on HBO

was only Part One of a

|

|

It was then repeated in 1988.

|

|

Here in the US,

The Golden Age of Buster Keaton went straight to HBO as a stand-alone feature — in 1979, four years after it was made.

Three Comedies was split into, you guessed it, three comedies.

Bill Scott’s intros were missing, for the simple reason that they had never been included.

Whether they were actually filmed, I have no clue.

At least one of these Three Comedies popped up on premium cable channels to fill in gaps between features.

That is how I saw the Jay Ward edition of The High Sign,

which magically appeared on my TV screen, unannounced.

Fortunately, I already had my VCR running and so I caught it, by sheerest luck.

Unfortunately, I no longer have access to that tape. Darn.

The other two?

If they played on American cable, then I missed them.

Atlas issued the Jay Ward editions of

One Week and

The Paleface on VHS in Germany in 1993.

Virgin Video released them on VHS in the UK in 1987 (VVD 274) and then again in 1993 (catalogue number unknown).

Apparently Skema in Italy also released them on VHS (K 028), but I don’t know when.

The Three Shorts, by the way, were windowboxed for 1:1.85 projection.

I suppose that once Ray Rohauer had these Three Comedies in hand,

he probably sometimes shipped them out to cinemas that booked those titles,

rather than ship out his earlier prints.

Somewhere in storage, I still have my EP-speed VHS of The High Sign.

Did I label it? I don’t know.

Can I find it? I don’t know.

Did it survive the elements these past few decades? I don’t know.

You can kinda sorta see it here,

a different print with different titles, but with the same music, though slowed down to match a slower transfer.

|

|

Ah. Look at this!

IMDb.com, The Paleface, Alternate Versions:

“The version shown on the American Movie Classics channel

was copyrighted in 1968 by Leopold Friedman and Raymond Rohauer.

It had an uncredited music soundtrack and ran 21 minutes.”

Hmmmmmm. That was different from the edition used in Three Comedies.

|

|

I recognize some of the music in Three Comedies.

One piece, coincidentally, was the same as a cue

in the “sound” version of Spite Marriage.

(Fritz Stahlberg compiled the

standard music cues for the “sound” version of Spite Marriage

and conducted the MGM orchestra, one cue at a time, each cue spliced to the next.

Apparently, a couple of the cues (which ones?) were original compositions by William Axt and Edward Cupero.

To this were mixed some

|

|

The second one, called Three Shorts,

consisted of The Paleface, The High Sign, and One Week —

it was pretty much just the three stuck together, and linked by Bill’s

narration. Joe Siracusa did the music, and again he used some Spike Jones

people like George Rock; he got these authentic 1912-era pit-band scores

from Milt Larsen [proprietor of the Magic Castle and Variety Arts Library]

and these were real silent-movie scores. They were recorded and interspersed

with original piano tracks composed by Johnny Guarnieri.

|

|

It is interesting to me that 1975 saw three Jay Ward releases of Buster’s works:

The Golden Age of Buster Keaton,

Three Comedies, and

Sherlock Jr.

In the US, Golden Age went straight to premium cable,

Three Shorts I think was actually entitled Three Comedies, and it went straight to premium cable as filler,

and Sherlock Jr. got individual bookings as a second bill to The Hound of the Baskervilles.

Those, together with the 1970 edition of The General,

should have been major releases, but there was a failure of imagination at every stage of the game,

and all three were invisibly dropped onto the market as afterthoughts and they all vanished before they could be noticed.

|

|

And this is what drives me nuts.

Yes, we all want to recover the filmmaker’s original intentions,

the filmmaker’s original edit,

the filmmaker’s original framing,

the filmmaker’s original tinting,

the filmmaker’s original preferences.

I am no different.

Yet there are some alternative releases — not all, but some — that, while not authentic,

are an important part of the historical record.

Why would we not want to have Joe Siracusa’s scores played by members of the Spike Jones band?

(Read an

article by Joe Siracusa! That’s not a suggestion. That’s a command.)

Why would we not want even to have the ability to see what our parents and grandparents saw fifty and sixty years ago?

Such alternatives should not be suppressed.

They should be available, not as substitutes for the filmmaker’s originals,

but at least as supplements on DVD and

|

|

Skip Craig said that the Jay Ward version of The General was shown on HBO.

That sent me on a wild-goose chase for months.

Skip Craig had misremembered the order of the features he worked on,

he misremembered the year,

he entirely forgot that one of the films was released,

he misremembered the narration,

and he misremembered who transmitted The General on television.

I know for certain that it was shown on cable.

I know that because, sometime around 1990, Chuck Van Dusen ran off a VHS copy for me, and it is now somewhere in my storage locker.

Been in storage for 22+ years.

My memory is growing dim. I need to see that tape again, that very tape, the exact tape that Chuck gave to me.

I’ll try to dig it out someday in the foreseeable future. Hope I can find it.

I should digitize it before the tape rots.

Hope it hasn’t rotted already.

After several decades in an outdoor storage locker, though,

I fear that it may well have passed on to that Great Azimuth Head Drum in the Sky.

|

|

HBO began transmitting on 8 November 1972.

Bill Scott’s edition of The General was issued to cinemas in September 1970.

I once knew two people who recorded it either on Betamax or on VHS.

Betamax was first put on the US market in May 1975 and VHS in June 1977.

I subscribed to HBO from about October 1984 through April 1987, and it was not shown during that time.

So, it may have been shown sometime after May 1975 and before October 1984.

Searches through the online newspaper archives are coming up blank.

Some but not all HBO Guides are

on the WayBackMachine and on

Archive.org,

and a few more can be found scattered about the Internet:

March 1982,

April 1982,

June through October 1982, June and November 1983, and

May 1984.

Of course, the one I need is missing.

Issues to seek out: 7/75, 9/75, 12/75, 2/76, 3/76, 4/76, 10/76, 1/80, 3/80, 5/80, 6/80, 7/80, 8/80, 10/80, 11/80, 12/80, 2/81, 4/81, 5/81, 6/81, 7/81, 8/81, 11/81,

1/82, 2/82, 5/82, 11/82, 12/82, 1/83, 2/83, 3/85, 4/83, 5/83, 7/83, 8/83, 9/83, 10/83, 12/83, 1/84, 2/84, 3/84, 4/84, 6/84, 7/84, 8/84, 9/84, 10/84.

Was it shown after April 1987? Possumbility, but I have my doubts, and no search reveals such a transmission.

So, it’s almost gotta be in one of those. Unless it isn’t.

The punch line, predictably, is that it was never on HBO after all.

HBO transmitted three other Jay Ward releases:

The Crazy World of Laurel & Hardy in

June 1979,

The Golden Age of Buster Keaton in

July 1979

and again in May 1980,

and

The Vintage W.C. Fields in

August 1979.

That’s about where I was expecting to find The General, spring or summer or autumn 1979, but no such luck.

If The General had been shown on HBO, I would have found the listing by now.

It was never on HBO.

|

|

If you know of any occasions when Jay Ward’s version of The General was shown on

|

|

Aha! A clue. Okay. That was after 4 May 1979 but before 17 October 1979, in or near Los Ángeles, California.

The programming that Jerry Buck mentions was all on a service called ONTV,

and it all seems to have been from May 1979.

I see that Wikipedia has a good article about ONTV,

which puts some things into perspective.

I cannot find any ONTV listings for the Welles flick or the Welcome flick during that half-year, or for the

Holly movie, either,

but it turns out that not all of ONTV’s programming was mentioned in the newspaper listings.

Bloodbrothers was on ONTV Channel 52 on

Sunday, 6 May 1979.

We might be getting somewhere.

The Campbell thingamaroo was on ONTV 52 on

18 May 1979.

Dog Day Afternoon was on ONTV 52 on

22 May 1979.

All right, the situation is beginning to come into focus.

We see that Buck was glued only to a single channel, not to a plethora of transponder choices.

So, The General was on ONTV 52, commercial-free.

ONTV was not part of a cable package.

It wasn’t even cable.

It was its own station, a local over-the-air station, a single channel, scrambled during the evening,

and to see the evening programming required a monthly descrambling fee.

In Los Ángeles it was broadcast on UHF Channel 52.

Ah. I see that nearby Santa Clarita listed The General on Channel 52 on

Tuesday, 6 November 1979,

and I assume that was the same as ONTV.

This was almost certainly the 1970 Jay Ward edition.

Yes, we really are getting somewhere.

After you search for months and months and months, and when you finally discover one teensy-weensy itty-bitty little clue,

you unleash an avalanche.

|

|

As you can see, Channel 52 was called “National Subscription TV,”

a term that seems not to pop up anywhere else in the country, not yet, anyway.

It was a local channel, not a “national” service, though plans to expand elsewhere were underfoot.

I’m searching all the US listings for 1979 to try to find any parallel transmissions of The General,

but there were none, since ONTV as yet had only this single station.

It would not get its second station (Detroit) for another two months.

|

|

I suppose that ONTV mailed its subscribers a monthly program guide.

If you have the program guide for May 1979, I’ll pay you a hundred bucks for it. Deal?

If you don’t want to give it up, I’ll pay you fifty bucks for a scan. Deal?

Lemme know.

|

|

The General popped up in

January 1980 on Niagara Falls International cable Channel 10, and that was presumably the Jay Ward edition.

“International” must have referred to Canada/US, since the city is bisected by the river, and each half is in a different country.

And oh hey look at this!!!!!

Niagara Falls International Channel 10 was HBO!!!!!

Except that it wasn’t.

Channel 10 paid for a select few HBO programs.

The rest of its time slots were filled with product acquired from elsewhere.

|

|

So, the Niagara Falls transmissions were on

Wednesday, 2 January 1980, and on

Saturday, 5 January 1980.

I do not see The General listed anywhere else in the country at that time.

Just to be sure, I ordered a January 1980 HBO Guide,

but I suspect that The General won’t be mentioned anywhere in it.

And it just arrived and I was right: no mention at all.

It was never on HBO, I’m certain of that.

|

|

I see that The General was also shown on New Jersey cable on

Sunday, 7 March 1982.

That was on something called Storer Communications of Gloucester County, Inc.

Again, I presume that was the Jay Ward edition, but I have no way of knowing for certain.

Might that have been when a New Jerseyan I once knew recorded his own VHS copy?

Possibly, but I don’t think so.

|

|

I am convinced that HBO never transmitted The General,

but, rather, that The General was transmitted by local cable stations,

at least one of which had contracted also to present the occasional HBO program.

|

|

Skip Craig got confused; he mixed up ONTV 52 with HBO, just as he had mixed up 1970 with 1974.

He misremembered that it was on HBO because several of his other movies were on HBO.

|

|

How many hours did I spend on that investigation?

Maybe a hundred?

Why?

|

|

So let me spend a little more, but only a little.

The Jay Ward edition of The General was on

Showtime in April 1986.

|

|

Ohhhhhhh, that bites.

I had a subscription to Showtime in April 1986 but I didn’t even notice this listing!

Pain. Misery. Shame. Frustration. Humiliation.

I had it right in the palm of my hands and I totally fumbled it. Drat!

Anyway, the capsule summary above was the usual one that was used from early 1979 through early 1987.

I wonder how many viewers found that summary sufficiently enticing to be tempted to tune in.

|

|

Chuck recorded the Jay Ward edition of The General when it was Showtime, and my New Jerseyan friend probably did the same.

Monday, 7 April 1986;

Friday, 11 April 1986;

Saturday, 26 April 1986.

|

|

Oh wait a minute. I remember now.

I was in Australia on the 7th and still on my way back home on the 11th.

I totally missed that final date probably because I hadn’t caught up on my mail.

Drat! Phooey! Fiddlesticks! Darn! I could have recorded it. Aaaarrrrgggghhhh!!!!

Anyway, yeah, now it comes back to me.

The VHS that Chuck gave me was from Showtime. Yeah.

|

|

If you have the April 1986 issue of the Showtime bulletin, I’ll pay you a hundred bucks for it. Deal?

If you don’t want to give it up, I’ll pay you fifty bucks for a scan. Deal?

Lemme know.

|

|

It was presumably the Jay Ward edition that was on TNC The Nostalgia Channel on

Saturday, 14 February 1987, and Saturday, 21 February 1987.

In eastern Canada, some unknown version of the movie was on First Choice from May 1987 through at least March 1988.

Some unknown version of the movie was on A&E repeatedly for two years, from June 1987 through June 1989.

That MIGHT have been the Jay Ward edition, since the running time was once listed as

“74 mins.”

rather than the usual 76 or 78 or 79 or 80, but that really might not mean anything, since the running times are often pulled from other sources.

Some unknown version of the movie was on the Z Channel in November and December 1987.

From May 1988 through sometime in 1989, some unknown version of the movie popped up on Super Channel in western Canada.

|

|

And now I’m bored and I don’t want to continue,

because I got the solutions to the mysteries that have been bothering me for decades.

Solution #1: Bill Scott confused ONTV with HBO, and he referred to the 30 May 1979 showing.

Solution #2: Chuck recorded it in April 1986 when it was on Showtime.

That’s what I needed to know.

|

|

When Ray died, his business was taken over by Alan Twyman.

The one and only time I spoke with Alan Twyman, which was in about early 1990,

I asked about this Jay Ward version of The General.

He gave me his deepest assurance that it would never be seen again.

“We all hated it. Everybody hated it.”

|

|

Look again above at the section on Claude Bolling.

You will see a Japanese LP with excerpts from his Keaton scores,

on an album entitled “Hello KEATON!”

Now, “Hello KEATON!” was the name of a film series

that began in Japan in maybe 1970 or thereabouts and continued at least through 1979.

The series consisted of Buster Keaton movies, reissued gradually.

On Yasurin’s Blog

for Saturday, 27 November 2021, we find, among other treasures,

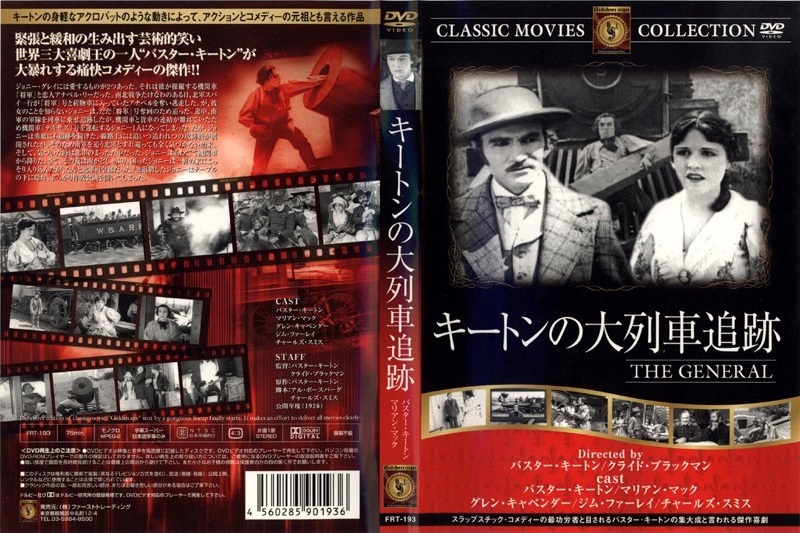

a chirashi for the “Hello KEATON!” reissue of The General in 1977. Ecco:

|

|

Now, like I say, I’m illiterate, and so I needed Google Translator to read to me what this chirashi says.

Click here to see what Google Translator told me.

The credits indicate that this is the “new version” with music by

Joe Siracusa and

Lou Fratturo.

By the way, it turns out that Lou was an arranger, and that he and Joe worked together on a

1970 album.

Ray Rohauer granted the distribution license for this to the Shibata Organization, Inc.

I assume the entire “Hello KEATON!” series had the same licensing arrangement.

So, in 1977, Japanese audiences were shown the Jay Ward version of The General.

Was this version ever put on video?

Were any of these “Hello KEATON!” editions issued on home video?

Just found this poster for the whole “Hello KEATON!” series.

It is beyond my budget, alas:

|

|

I have begun my quest.

My first acquisition:

|

|

No good. This is the Tarbox print, overscanned, a dupe of a dupe of a dupe of the MoMA print, originally at Harvard.

Well, it’s 24fps, so they got that much right.

The uncredited music is on some sort of a synthesizer that was set to sound like some sort of an organ,

and it was improvised by someone who seems never to have seen a silent film prior to this recording session.

This is from 1995.

|

|

Here are some video editions I have not seen but would be most interested in seeing.

Who knows? Maybe one of them has an interesting musical accompaniment?

Maybe one of them is the Jay Ward version?

|

|

If you are in Japan and if you are willing to purchase some of these videos and mail them to me,

I would pay you your costs as well as an honorarium.

If that prospect interests you, please write to me. Thanks!

|

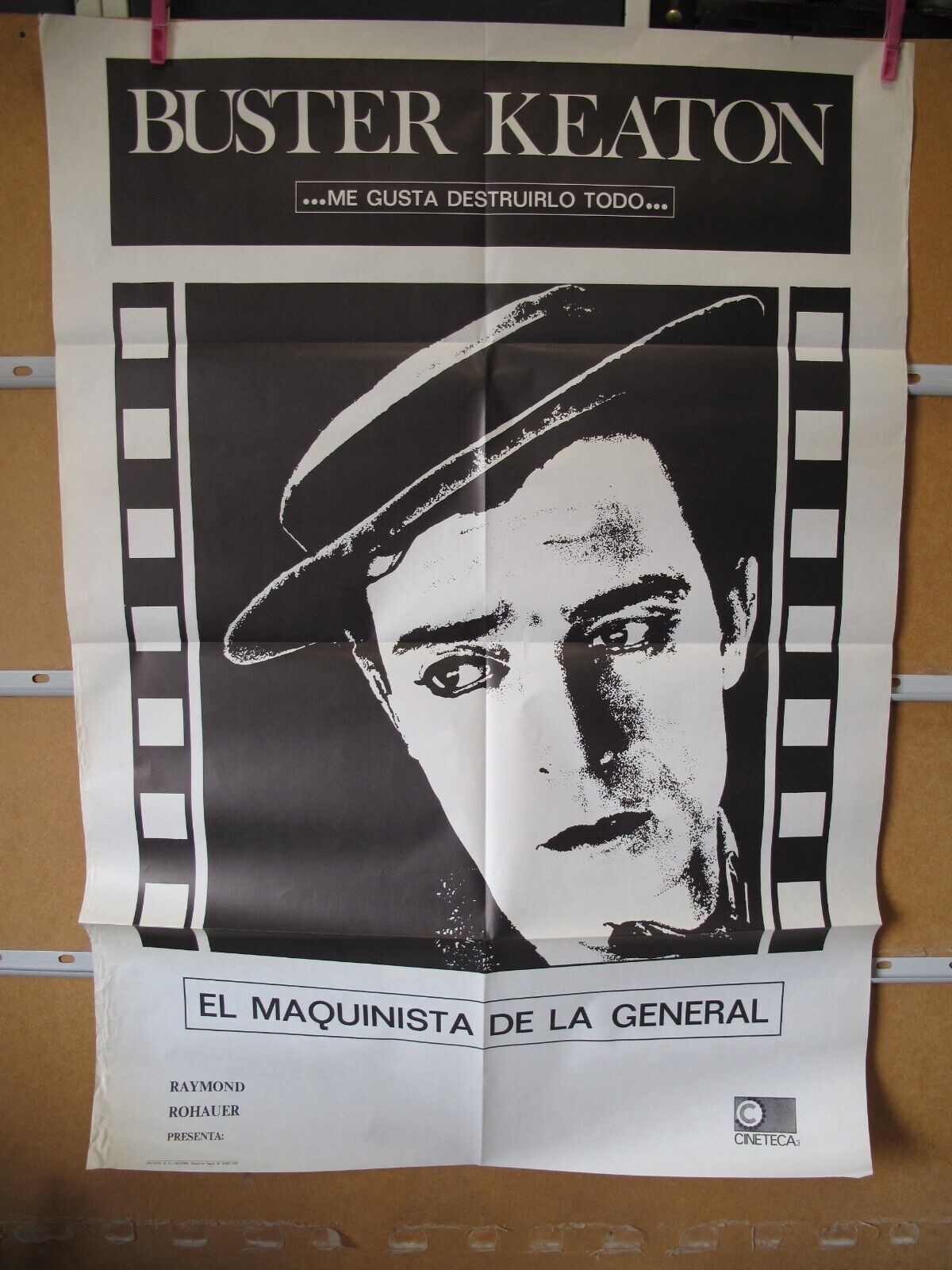

Found this on Spanish eBay, but had no idea what it was. The legend atop, “Me gusta destruirlo todo,” is not in keeping with Buster at all. Well, I just learned what this was! It was part of the 1972 Busterfest in Madrid! This was in June, when The General was still full-aperture silent. A few months later, that full-aperture edition would be replaced, as we shall learn right below. |

Rohauer’s 1972 Touring Edition |

|

Ray’s Festival prints were probably all reasonably complete and accurate.

Eventually, Ray ordered an edition of The General with Lee Erwin’s organ soundtrack.

This could only have been printed from the dupe negative of the November 1926 preview print.

Why do I say that?

First, because that’s what Richard J. Anobile used for his Rohauer-authorized photonovel in 1975.

Second, because that’s what Reel Images copied for its 16mm edition,

and there would have been no other place to access the 1926 preview print except through Rohauer,

without his permission, of course.

Third, because Rohauer was so terribly paranoid about letting his 16mm print out of his sight

when he played it in Buffalo, going so far as to carry it to the booth himself and never to take his eyes off of the reels,

and then carry the print out of the booth again at the end of the show.

He was paranoid not only because he was born paranoid; he was paranoid for good reason!

That’s why I conclude that this could only have been from that dupe neg that Rohauer ordered in January 1960

(without the Academy’s permission).

|

|

This edition was optically reduced from full-aperture silent (.723"×.980")

to the

|

|

The Kino

|

|

I hate to say it, but Lee Erwin’s score for this movie does nothing for me.

It’s just a couple of random themes,

principally a disguised staccato variation on The Teddy Bear’s Picnic repeated endlessly.

The score does not match the action or the mood or anything else.

It doesn’t enliven the film, but takes away from it

(sucks the life out of it would be more accurate).

The organ sound is distinctly thin, and so I was surprised to discover that it was played on a

Wurlitzer,

which should have

a rich, overpowering sound.

(By the way, Robert Israel and Joe Hisaishi, in their scores for The General,

similarly quoted The Teddy Bear’s Picnic,

which I thought was silly and detracted from the movie.

The movie is majestic, strong, powerful, stunning, sublime, and dignified,

while The Teddy Bear’s Picnic

is just a dinky little song for babies.)

|

|

I was in Albuquerque from 1972 through 1978, and Ray Rohauer was not.

I never had a chance to see the 1972 edition, but I’m pretty sure I know what it was.

Richard J. Anobile’s photonovel was pulled from a Rohauer print,

and he surely did not access a nitrate.

He accessed a copy negative or a

|

An Unexplained Announcement

What in the bloody heckleandjeckle was this thingamaroo?

My best guess is that this was a twentieth-generation 16mm public-domain print

with a

Might anybody know whatever became of the

Bown and Virginia Adams collection?

|

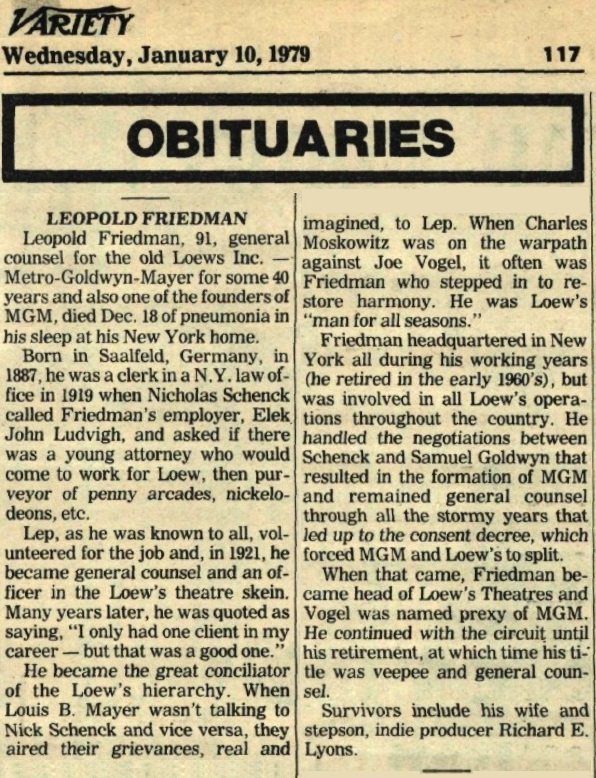

Leopold Friedman’s Obituary |

|

Took me forever, but I found it.

It was in Daily Variety, Wednesday, 3 January 1979,

repeated in the weekly Variety, Wednesday, 10 January 1979::

|

|

|

Once Friedman was gone, Ray Rohauer was the sole remaining owner of Buster Keaton Productions.

My guess is that once all the legal matters were settled over the next few years,

the domestic camera negative of The General migrated over to Rohauer’s possession.

|

Rohauer’s 1979 Release Edition |

|

This is strange. This is surely the KirchMedia edition with the Konrad Elfers score,

but 1 May 1961 is a mite too soon. Why did this wait until 1977 to get into the book?

|

|

When the Marion Mack tours had finished all their major playdates,

Ray hired Lee Erwin to

|

|

For this 1979 edition, Lee Erwin used his old themes, but he played them in an entirely different sequence.

You can hear his 1972 performance on the Kino K669

|

|

One would have thought that the series of Buster Keaton VHS tapes

that Atlas Film issued in Germany in the

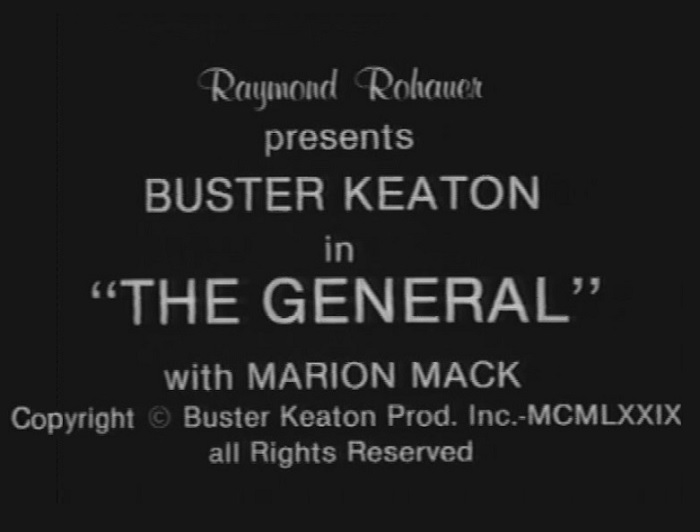

Above are the two opening main titles, which replace the original main title. A

14% crop was standard for telecines of the day

(and then TV sets at home in those days would crop a further 8% to 10% or thereabouts).

It was possible to defeat the default setting on the telecine and to scan the entire image,

but the techies who created this tape, or their boss, decided to abide by the appalling default.

Actually, they decided to make it even worse.

Only a handful of loonies like me ever complained, and we were unkindly shown the door.

The second title claims that this is “adapted from” the original.

As far as content is concerned, the only differences are the replacements of the main title and the deletion of the original copyright title.

That’s it.

And, of course, 22 frames deleted due to prior damage, and an appended music credit.

Maybe Ray added the occasional distinctive scratch that he and only he would recognize,

or maybe he deleted a frame somewhere to mark this edition as his,

probably during darkness between a

|

|

Ray put this new 1979 edition into his catalogue for cinemas to book,

and this is the edition that was at the Buffalo Film Seminars on 28 August 2001,

but I shut off the sound to allow

Jonathan Benjamin to accompany on electric piano.

Jonathan wasn’t local.

Phil Carli was away that week, and so he suggested that Jonathan take his place.

Jonathan flew in from somewhere to play the movie.

After the show, he complimented me on not cropping the film.

He said that all cinemas crop the film

(“they usually spread it out a bit,” was his euphemistic turn of phrase),

and so he was pleasantly surprised that night.

That made me feel good.

|

|

Below is the credit that appears after THE END:

|

|

Though Ray made no significant changes to The General,

he was not so kind to Buster’s other movies.

The prints he prepared for general release were ruined,

and those butcheries must have begun in 1967 or 1968.

Ray altered the films and copyrighted his new versions.

For many of the films, he rewrote the titles, killing the humor,

and he changed way too much, deleting shots and making other editorial decisions that rendered some scenes senseless.

If at all possible, he would sweep up all known copies of the original versions

and lock them away so that nobody else would be able to distribute them.

It would be nice, for the historical record,

if future

|

|

The prints made for regular bookings included music tracks,

and, more often than not, Ray added those music tracks by lopping off the left side of the image.

Also, some of his prints were cheaply made (chromagenic?) and looked perfectly dreadful.

|

|

Oh no. Wait. Wait. No. I’m wrong. No no no no no no no no no no.

For some movies featuring Suton Face, the Rohauer Collection did not include music tracks,

but shipped out

|

|

Only now, two decades later, does it occur to me.

The full-aperture prints that we received in Muskegon?

They must have been leftovers from 1970 or just afterwards.

They were gorgeous.

I mean they were gorgeous.

|

|

My memory does not match the listings.

Normally, I trust documentation over my memory.

Not in this case.

I trust my memory far more than I trust this documentation.

| |

ANNOUNCED SCREENINGS: 1999: One Week, Seven Chances 2000: One Week 2001: The High Sign, Steamboat Bill, Jr. 2002: The Electric House, College 2003: The Goat, The Haunted House, The Balloonatic, The Frozen North, The Paleface |

MY MEMORY: 1999: The Boat (cropped), The Navigator (cropped) 2000: One Week (reduced) 2001: The High Sign (full), Seven Chances (full) 2002: The Electric House (full), College (full), So You Won’t Squawk 2003: The Goat (cropped), The Haunted House (cropped), The Balloonatic (reduced), The Frozen North (reduced), The Paleface (cropped) |

|

By the way, So You Won’t Squawk, a dumb quickie made in 1941, got the best laughs of all.

That was the crowd-pleaser, that’s the one that brought down the house, much more so than the silent flicks.

Oddly, I was laughing out loud, too, but I realized it was just a dumb quick cheapie that was not worth a second look.

Sorta depressing to see that it was the audience’s favorite, though.

The masking was manual and the Academy and MovieTone formats were both run with the same pair of lenses;

so in 2003 we ran all five shorts at .6796"×.825", which is why the ones that were optically reduced

had visible black bars at the top and bottom.

There was really no other viable way to do it.

|

|

It was always a bit odd when distributors from the 1960’s through the 2000’s

shipped out full-aperture prints to commercial cinemas,

because there were literally only maybe three or four commercial cinemas worldwide that could handle that format.

(I know of the Sheraton Opera House in Telluride, CO,

and the Magic Colonial in Vancouver, BC.

Nowadays there might be as many as a dozen.

|

Original |

.446"×.825" widescreen crop |

Why is it that most people cannot discern any difference between these two presentations?

|

|

Hubert Rostaing |

|

I discover that Hubert Rostaing (1918–1990) scored some of Buster’s movies,

certainly The Paleface (Buster et les indiens, distributed by Les Grands Films Classiques, circa 1980)

and The General (Le mécano de la Général, distributed on video by

RCA Vidéo in 1981).

Does anybody know more?

Help?

Of course, there is the distinct possumbility that

Rostaing had nothing to do with these releases,

but that the distributor simply patched together old Rostaing recordings

and plopped them onto the films.

I do not know. I wish I did.

I wish I could find copies.

|

Television Reveals

|

|

Remember the final preview print?

Buster showed it at the Alex in Glendale on Friday, 12 November 1926,

and then stored it in his secret bunker.

James Mason excavated it at the end of 1955 and donated it to the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences in January 1956.

Rohauer, by crafting a business partnership with Buster, illegally using the firm name “Buster Keaton Productions,”

borrowed the Academy’s print at the beginning of 1958, and duped it.

His dupe served as the basis for the European/Japanese reissues of 1962 through 1970,

as well as of his own 35mm and 16mm festival prints of 1963 and 1972.

Somebody duped his 16mm dupe and issued it through Reel Images on 16mm and later through Video Yesteryear on VHS.

Remember all that?

|

|

Well, that very 35mm nitrate preview print ended up on television!

|

|

To get that final preview print shown on television required that Raymond Rohauer and Kevin Brownlow work together.

Nobody in the world could have predicted that the two would ever coöperate — least of all Ray and Kevin.

Raymond Rohauer and Kevin Brownlow had never been buddies.

Far from it.

Ray was underhanded, and in his paranoia, he suspected that Kevin was a rival.

Kevin diplomatically described Ray as “charmless.”

After decades of enmity, they found themselves in a quandary.

Each needed the other, desperately, to rescue Chaplin outtakes that had been presumed destroyed.

By a stroke of good fortune, Kevin’s business partner, David Gill,

was able to get along with both the combatants.

He kept Kevin and Ray away from one another and managed to broker deals.

That is how Kevin found himself in the unusual and sometimes uncomfortable position

of partnering with Ray for a series of film programs, at the cinema and on British television.

|

|

When Kevin needed to show The General on Thames Television in Britain,

Ray came to the rescue with a gorgeous nitrate print in almost immaculate condition.

Unlike the release prints presented at deluxe downtown cinemas in 1926 and 1927,

this print was not tinted, but was straight black and white.

Unlike release prints, this print had each shot physically spliced together.

Kevin and David recognized that this must have been a preview print.

It was.

This was the actual nitrate print that had been previewed at the Alex in Glendale on 12 November 1926.

|

|

The technicians at Thames Television 4 must have been limited in their choices.

They were unable to transfer the entire image.

Instead, they transferred only about .600"×.800", but recentered it to lop off the left and right equally.

They also reframed most of the film to reveal more of the bottom of the image and less of the top.

Unless one compares each image with an authentic copy, it would be impossible to tell that anything is amiss.

|

|

As the antique nitrate print ran through the telecine,

the image bounced as each cement splice entered the film gate,

and, a split second later, it bounced again as the splice rounded the intermittent wheel.

(Didn’t bother me at all, because, hey, it’s the preview print,

and that’s how the preview print behaved when it was shown to preview audiences;

but it bothered an old acquaintance so much that he couldn’t watch the video.)

This unusual print can only have been the very print that was projected at the Alex in Glendale

and perhaps also in San José.

This Thames Television edition was soon afterwards issued on home video,

and it did not include the “Copyright by Joseph M. Schenck” credit.

That credit was not included in the preview print, but it would be added in time for the release.

|

|

This new transfer of the old nitrate

was broadcast on Thames Television on 7 October 1987, with a lush orchestral score compiled, composed,

and conducted by

Carl Davis,

and it was easily the finest score ever recorded for the film,

and easily one of the finest scores composed for any film.

It is easily one of the finest accompaniments I have heard for any film, silent or sound.

It matches not just the action, not just the theme, not just the visual compositions, not just the pacing and rhythm,

but it also matches the flavor and texture of the story, and it blends the themes,

sometimes playing two themes, one over another, and makes the two themes sound exactly like a single theme.

The very opening,

|

|

The one time I met Eleanor (Buster’s widow), I remember her speaking, in awe,

about how thunderstruck she had been when she first heard Carl Davis’s orchestral accompaniment.

I could be confabulating, but I seem to remember her saying that it gave her goosebumps.

There are other fine scores, yes (Bill Perry, Gaylord Carter, Joe Hisaishi, and others),

but once you hear Carl Davis’s score, you will be spoiled.

If you are a film composer, you will be intimidated.

|

|

A repeat broadcast, this time on Film 4 Grandad’s Theatre, Buster Keaton - The General (1926) - With Original Music Score, uploaded on May 7, 2016 https://youtu.be/NxM2F4buF3Y |

|

Linux Pronto, Come vinsi la guerra (The General) - Buster Keaton (1926) uploaded on Jul 17, 2022 https://youtu.be/IUwvGE8BHlI As broadcast on RAI DUE in Italy, though when I do not know. The voiceover translation irritated me until I heard “egli” as opposed to the modern “lui,” and that’s when I forgave it, totally, completely, absolutely. |

|

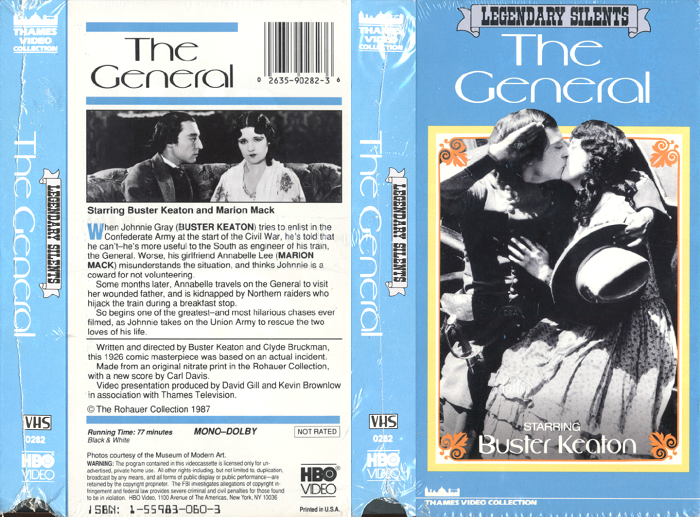

This television edition of the movie was a revelation.

It was vastly superior to anything that anyone had seen before,

and two years later it was issued on VHS in the US.

That was on 8 November 1989 through HBO, though the only date printed on the cassette was 1987.

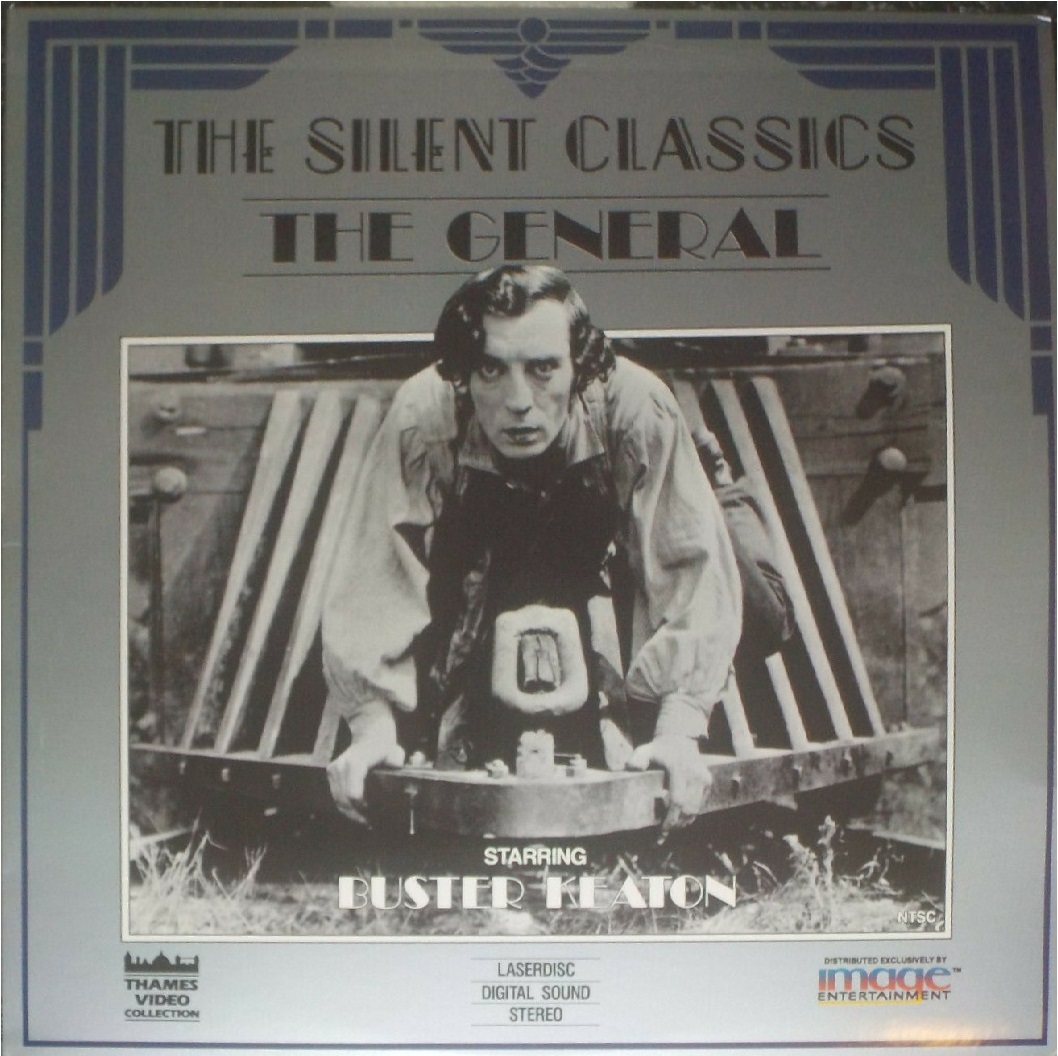

It seems to have been sometime in July 1990 that it was issued on laserdisc through Image Entertainment.

Lastly, it was issued in the UK from Thames Video sometime in 1991.

This was the most desirable edition of the movie, but not too many people knew about it.

The problem was the price.

At a time when the VHS market had settled on $18.95 as the going price for pretty much any tape,

HBO’s suggested retail price was a whopping $39.95.

At that price, few shops even bothered to stock it,

preferring to purchase instead the worthless |

|

Later, Ray granted Kevin access to the original domestic camera negative (OCN),

but not out of the goodness of his heart.

He handed it to Kevin only because he knew that Kevin would not be able to resist raising funds

and finding a lab to make a proper preservation copy.

That saved Ray from the trouble and expense.

The advantage for all of us is that Carl Davis’s score

has since been synchronized to editions derived directly from the original negative,

and the results are glorious.

|

|

If you wish to hunt for a video of this version, here is what you need to look for.

First came the US, with an NTSC conversion that was issued on VHS from

HBO’s “Legendary Silents” label, 0282, with a 1987 copyright,

but first issued on 8 November 1989:

|

|

|

Next came this same NTSC conversion but now on laserdisc from Image Entertainment, ID6862HB.

Program content copyright 1987 by The Rohauer Collection.

Artwork and Summary copyright 1989 by Home Box Office, Inc.

Package/Design copyright 1989 by Image Entertainment, Inc.

This was issued in or around July 1990.

|

|

|

Last was the Thames Television International/Video Collection International, Ltd., in Hertfordshire,

on PAL-system VHS, product number TV 8129, which was issued sometime in 1991.

|

|

|

It was 77 minutes rather than the expected 79, not because of cuts,

but because it was transferred at the PAL speed of 25fps, and, further,

beginning with the theft of the train and for the next few scenes,

the speed was stepped up to 26fps.

Why? They thought it looked better that way.

Well, those few scenes, yeah, I’ll concede, they look okay when sped up.

I personally don’t think they look any better, but they don’t look worse, either.

|

|

This little note will bore you. You can skip it.

Something just occurs to me.

When I first saw this video edition, initially on VHS,

I was a bit surprised to see grease-pencil cue dots at the ends of reels 7 and 8.

A 1,000' reel, if full to the brim, lasts about 11 minutes at 90'/min.

Rare is the reel that is filled to the brim.

Beginning in 1930, MGM instructed the lab to place cue dots onto its film towards the end of each reel.

8⅓ seconds before the reel runs out, there is a

cue dot, visible on screen, in the upper right corner,

and it lasts for four frames (⅙ of a second).

The projectionist turns on the motor of the second projector upon seeing that.

Then, 7⅓ seconds later, there is a second cue dot,

telling the projectionist to kill the old projector and go live with the new projector.

Prior to the invention of cue dots, there were three other methods.

Maybe more, but I only know of three.

Originally, each reel ended with a title shown on screen: END OF PART ONE, or END OF PART TWO, or END OF PART SEVEN, or whatever.

The following reel opened with a title shown on screen: PART TWO, PART THREE, PART EIGHT, or whatever.

Those were the projectionist’s cues, and so now you know why posters for movies of that vintage

announced things such as “A COMEDY IN TWO PARTS” or “A DRAMA IN SEVEN PARTS” or whatever.

Apparently, some cinemas got the (not so) bright idea to punch holes into the film

and to use those

In 1924, Metro pioneered a new method.

Oh. No. It wasn’t Metro.

I think it was First National that pioneered this method.

Reel endings were placed in the middles of titles.

So, if a character says, for instance, “I wish to climb that mountain tomorrow,”

that title might be placed right at the end of a reel, and it will be held on for an extra long time.

The projectionist receives a cue sheet that tells him (usually him) that

“I wish to climb that mountain tomorrow” is the cue to switch to the next reel.

So, as soon as the projectionist sees that title on screen,

he hits the motor switch on the next projector, and as soon as he hears that the motor is up to speed,

he slides a metal plate to block the image from the old lens and to open the image emanating from the new projector.

The new reel begins with that exact same title: “I wish to climb that mountain tomorrow.”

An alternative method, perhaps used at Metro, certainly used at Paramount and Warner Bros.,

gives the projectionist different sorts of cues:

“When you see Susan trip over her shoe, start the motor of the next projector.

When she slams the door, change over.”

For safety, when Susan slams the door, the camera will linger for several more seconds.

The next reel will open either with another image of Susan slamming the door,

or it will open with a lingering shot of something else, with no action for several seconds.

That gives the projectionist some slop factor when switching from one projector to the next.

But for a preview print, what do you do?

The editing is not sufficiently refined that such seamless

So, when we watch this 1987 video, we are seeing exactly the same grease-pencil cue dots

that the preview audience saw at the Alex in Glendale that night in November 1926.

At least, we’re seeing them at the end of reel 7.

The cue dots on the earlier reels must have been wiped off,

and the beauty of grease-pencil cues is that they can be wiped off quite easily,

especially if they are on the base side of the film.

At the end of reel 8, the final reel, we see a curtain cue followed a few seconds later by a motor cue.

It seems that the final cue was never inserted, since the fade out was cue enough.

Since there was a curtain cue followed by a motor cue,

then I can only assume that, at the Alex,

the plan was to have the curtain close at the end of The General,

but that at the instant the curtains finished closing, they would open again

for the beginning of the evening’s regularly scheduled feature.

There was to have been no pause between the two movies.

Yet there was a pause, and the projectionist certainly stopped the show and brought up the house lights in response to the ovations.

Anyway, now that I’ve been examining the

Kino K669

I would be surprised if even one other person on the planet finds this interesting.

|

|

Those video editions, of course, were issued only after Ray died.

You see, Ray absolutely refused to allow most of the films in his catalogue to be sold to collectors,

but, in the days before affordable home video,

he did allow Richard J. Anobile to issue

a book of frame blowups from the full-aperture festival print of The General (Avon Books, 1975).

By some inexplicable quirk, every last frame blowup was out of focus.

It was great to have that book anyway, because it included the pieces missing from the Killiam version

that was available to collectors in 8mm and 16mm.

It also had a really nice interview with Marion Mack.

Right after Ray died, Virgin Video in the UK began releasing a series of “Rohauer Collection” VHS tapes.

Then Atlas six years later began issuing films from the Rohauer Collection on VHS.

So much changed, so rapidly, the moment Ray died.

|

|

Carl Hultberg, in his book Rudi (and me) (2013), pp. 69–70,

articulated one of the most widespread gripes about Ray Rohauer.

Let us take a look:

|

|

Because even though James Mason was obviously an SOB,

Rohauer was an even bigger one. Once reacquired, all Keaton’s

classic movies came under Rohauer’s control. That’s why for

about thirty years it was next to impossible to see the filmmaker’s

work. Rohauer simply priced the rentals so high that movie

houses had to lose big money to have a Keaton festival. They

could kiss his ass. The films didn’t come out on VHS until well

into the 1990s. Rohauer thought he knew how to milk a good

thing. Poor Buster. Had he just exchanged one abusive family

(Joe and Myra) for another? Starting in the early 1960s Rohauer

and Eleanor drove the clearly ailing Keaton like an old farm horse.

It is painful to see them on camera in a 1980s Buster Keaton

documentary (Rohauer in a ridiculous baby blue polyester suit)

wondering if maybe they might have pushed the old guy a bit too

hard. This of course was after Buster Keaton the genius died

suddenly in February of 1966 at the age of seventy.

|

|

Nearly everything in the above paragraph is wrong,

except Ray Rohauer’s refusal simply to add the Buster movies to any old catalogue

for any old repertory house to book at $30/week flat rate.

The movies would have been seen even less had he done that and Buster’s reputation would have tanked.

Ray made sure to keep interest high and he made Buster a star again.

It was not The Lovable Cheat or Beach Blanket Bingo

that earned Buster $160,000 in royalties and international fame.

It was the European and Japanese reissues of the silents that earned Buster

about $160,000 in royalties and tremendous fame and massive amounts of attention.

Ray was instrumental in that.

Ray was the one who put Buster back in the limelight where he received standing ovations as a matter of course.

Had Buster’s movies been used as mere filler on local TV stations

or if they ended up in the bargain bins at video shops, they would never have been noticed.

What people condemn Ray for is what I admire Ray for.

|

|

The best article I have ever seen on Ray is by Ed Watz,

“Raymond Rohauer: The Man Who Would Be Keaton” (click to page 16),

Comique: The Classic Comedy Magazine vol. 1 no. 2 (Spring 2022).

Another worthwhile source is Bill Everson,

“Raymond Rohauer: King of the Film Freebooters,”

Grand Street no. 49 (Summer 1994), pp. 188–196.

Tempering those two accounts is Tim Lanza’s chapter 17,

“Raymond Rohauer and the Society of Cinema Arts (1948–1962),” in

David E. James and Adam Hyman, eds., Alternative Projections: Experimental Film in Los Ángeles, 1945–1980

(New Barnet, Herts.: John Libbey Publishing Ltd; Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press, 2015; download and then click to page 129).

There was also a hit piece by John Baxter,

“The Silent Empire of Raymond Rohauer: The Ever-Expanding Power of the Cinema’s Strangest Mogul,”

The Sunday Times Magazine, 19 January 1975, pp. 32–33, 38–39.

Worth a read.

I found it fascinating and delectably juicy.

Then I read it a third time.

What John Baxter did to Ray Rohauer is exactly what Marion Meade would later do to Buster.

It was just a nasty smear, a hatchet job.

A third reading convinces me not to bother with anything that John Baxter has ever written.

There was another intriguing article in Tony Slide’s magazine, The Silent Picture,

which I have somewhere in my storage locker.

I think the article was called “The Silent Film Mafia.”

When I eventually dig it out from my distant storage locker, I’ll provide the full reference.

Ah. I got to my storage locker.

It is not called “The Silent Film Mafia” at all.

It is by Kevin Brownlow, and the correct title is “Not Another Silent,”

in issue 10, Spring 1971, pages 3–4.

In that article, Kevin carefully avoids mentioning Rohauer’s name,

though those in the know can easily recognize who he is writing about.

There’s yet more info in Kevin Brownlow’s The Search for Charlie Chaplin.

There is an interesting chatgroup discussion about Rohauer at

“What happened to Raymond Rohauer’s film archive after his death?,” and another at NitrateVille.

|

|

For years, I thought that Rohauer was worthy of a book.

He was peculiar.

He had a genuinely nice side, and a few people really liked him. Very few.

He was also a pathological liar.

He did not look like a con artist;

he looked like a nebbish.

Yet he was manipulative, egomaniacal,

|

|

Yet history will be kind to Raymond Rohauer.

Other restorationists, other distributors, other preservationists, other archivists

did important work, but they made sure to keep silent cinema in the realm of a handful of enthusiasts.

Had Buster’s films been rescued and preserved by a museum or an archive,

he would have remained an obscure figure, a name occasionally spotted in a footnote,

and his movies would have popped up at rare times in hidden screening rooms, accompanied by a tinkling piano,

shown to a group of a dozen or fewer history buffs.

Raymond Rohauer would have none of that.

Ray’s goal was to make Buster a superstar and to make his silent films major

|

|

Archivists despised Rohauer, and for good reason,

since he was finding ever-newer ways to swipe their collections from them,

but, in the final analysis, they benefited from his skullduggery.

Ray rescued lots of movies that would otherwise have vanished off the face of the earth.

Ray did more than rescue ancient movies; he publicized them effectively

and he found young and enthusiastic audiences for them.

No other distributor or exhibitor was doing that.

No other distributor or exhibitor knew how to do that.

To Ray, it came naturally, and he was literally the best thing that could have happened to Buster’s movies.

I can’t take that from him, even though he did butcher Buster’s films

and even though he was often (not always) horrid.

Though he did it only for his own self-aggrandizement and not out of the goodness of his heart (did he have a heart?),

he gave Buster something that no one else had ever given him.

Unlike Joe Schenck, unlike MGM, unlike any of the movie studios,

Ray Rohauer offered Buster full control of his films, and not only offered control, but insisted upon it.

That’s why I can’t hate the guy.

It would be simplier if I could, but I can’t.

Then I decided that, no, he’s not worthy of a book.

He’s worthy of the above articles.

They are enough. They’ll do. A book? No.

Now that I’m learning more, I have changed my mind once again.

He is most definitely worthy of a book, a good, solid, comprehensive book,

one that would do him and others full justice.

|

|

Further to give the guy his due, though, it was Ray who got Buster’s movies shown in Venice in September 1963,

and that is how Italians discovered the filmmaker.

Buster was then invited to attend the Venice Film Festival in 1965,

since the movie he had made for Samuel Beckett,

Film, was on the program.

Buster was shoved unwilling onto the stage (reportedly by Rohauer),

and there was a sudden standing ovation.

There was a repeat later that evening, when he and Eleanor took their seats in the balcony.

Legend has it that it was the greatest and longest standing ovation in the history of the Venice Festival.

Buster was in tears.

“This is the first time I’ve been invited to a film festival, but I hope it won’t be the last.”

(I would like to think that Tinto was in the midst of that standing ovation,

since he was a prominent Venetian and regularly attended the festival,

but I don’t know and I can’t ask him.

I looked at the photographs but I don’t recognize anybody.

Tinto’s good friend

Lorenzo Codelli was certainly in that audience, though.

I wonder who else was there.

If you want to learn the background of Beckett’s film of Film, see

Notfilm, also available as a double-disc set on a

British

|