Jay Ward Productions and Sherlock Jr. |

|

As we learned in the last chapter,

Jay Ward offered a revised edition of The General doubled with a threesome of W.C. Fields shorts.

Well, a few years later, Jay Ward followed up by reissuing Sherlock Jr.

|

|

When I saw the Jay Ward version of The General,

it was not on the same program as the Fields shorts.

Those days were long gone.

Instead, when I saw it, it was double billed with Sherlock Jr..

|

|

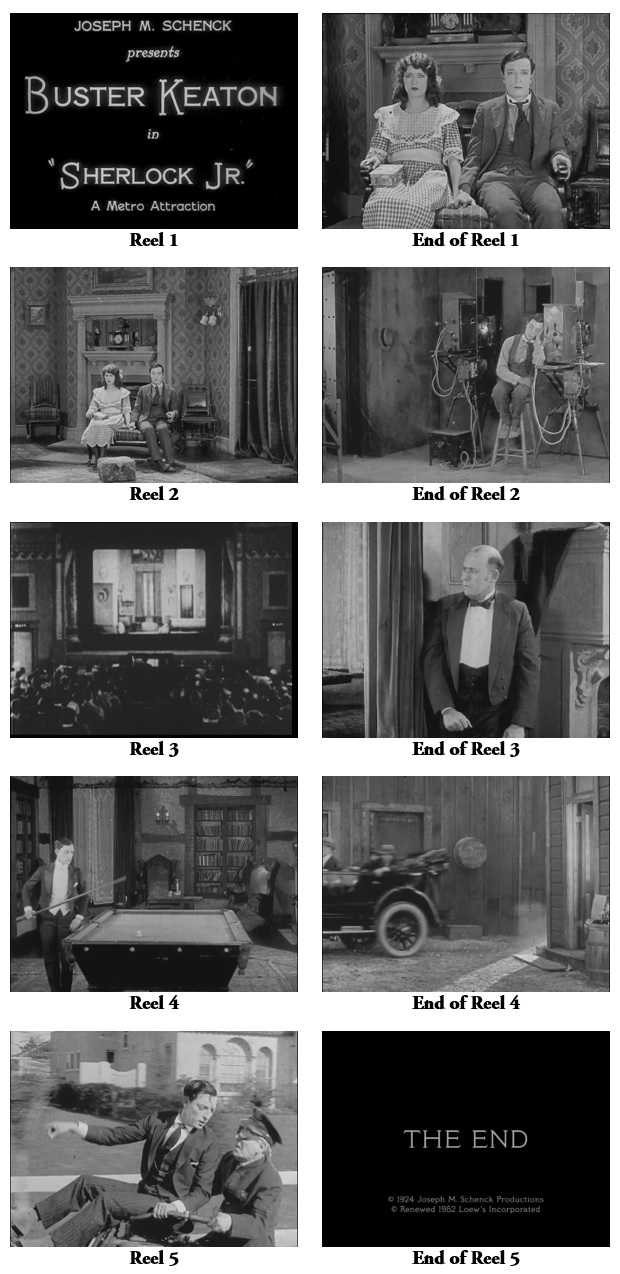

Before we proceed, let us remind ourselves a little bit about Sherlock Jr.

Back in 1924, per contract, Buster chopped this movie down from six reels to five, each reel lasting about nine minutes.

That is how we can figure out that Buster’s original preview print

was up to about nine minutes longer than the current versions.

Probably it was no more than about five minutes longer, really.

After testing it with preview audiences and revising it until it was just right,

Buster was satisfied with the short version, mounted onto five short reels.

He shot with up to four cameras side by side,

to create a domestic negative, an export negative, and probably some emergency backups, too.

The cameras were motorized and mechanically ganged,

and so they synchronized perfectly.

|

|

As she so often does, Olga Egorova filled me in about the previews.

I knew about the

|

|

Note the reel counts. Six? Seven? Five?

When it was first previewed, it was presumably mounted onto six reels, but I bet those were six very short reels.

The reference to seven reels was surely a typographical error.

|

|

Above we have a name of interest, most notably Richard Pyle.

Who was he? Did he appear in the final film?

Another name of interest is George Davis.

In a preliminary version, never seen by the public, he was a member of the movie audience.

In the final film, he is one of The Sheik’s band of thieves.

|

|

Who on earth was

|

|

Ah! Another name!

John Patrick.

Who was he?

|

|

The above booking was canceled, as we soon discover.

|

|

So, after the previews, Buster and his crew shot replacement scenes on Friday and Saturday, 14 and 15 March 1924.

This probably explains why the booking in Roseville was canceled.

|

|

The preview mentioned in the article above was not for the public.

It was strictly for the Metro brass.

|

|

Roscoe had left back in November or December,

though he was still on Buster’s lot shooting his own short pseudonymous comedies.

|

|

The above tidbit is intriguing. So there was a third preview at a Los Ángeles cinema at midnight?

That would not have been announced anywhere.

The audience members for the last show of the night would have been surprised when

the manager walked onto the stage to invite them to stick around for a little while to see something special.

We’ll probably never know when or where.

|

|

As you know, there is always the

|

|

|

Sherlock Jr. opened on 14 April 1924.

It then wended its way across the Western world through the end of 1926 and then it was gone.

It was probably in about 1937 that MGM sold a lavender to MoMA,

which made a print that it occasionally showed to the public.

In 1941 or thereabouts, MoMA made a 16mm copy of the film available to educational institutions.

So, if people wanted to see the movie, MoMA was the only game in town.

|

|

In the summer of 1954, Ray Rohauer took possession of the decaying workprint that Buster had in his garage,

and he paid General Film Laboratories in Hollywood to make a cropped 16mm print

(top and left missing, as it was wrongly printed through a sound gate).

My best guess is that this print was a poorly made reversal.

My best guess is that Ray held on to Buster’s decaying print for a few years

until he could save the money to have General Film Laboratories make a proper dupe negative.

|

|

In early February 1956, at the request of Robert Smith and Sidney Sheldon,

who were preparing The Buster Keaton Story,

Ray showed his entire collection of cropped 16mm prints of Buster movies to student audiences at USC

and perhaps at other universities in the area as well.

This collection included Sherlock Jr.

|

|

In early 1960, Ray borrowed from the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences the nitrate

that James Mason had donated, and he paid General Film Laboratories to make a 35mm dupe negative, but one reel was missing.

A good guess would be that Ray took the best parts of both nitrate copies to assemble a better master.

|

|

Ray could not show these films to the general public, since the rights were tied up.

Loew’s wrongly claimed ownership to a number of the films for which it had mistakenly renewed the copyrights.

The Schenck successors claimed ownership, though many of the rights had lapsed.

Leopold Friedman continued to license materials for which he had never submitted copyright renewals,

and which were therefore in the public domain.

Several films, though, truly were still under copyright.

This led to legal battles that continued for years.

Finally, at the beginning of 1960, a savior appeared.

Hans Andresen of KirchMedia in West Germany wished to reissue Buster’s silents,

and so he managed to consolidate the Loew/Schenck/Friedman rights.

I assume it was his legal counsel who made those arrangements.

That allowed Buster and Ray to have sufficient control to license the films.

|

|

In conjunction with the pending KirchMedia reissue of The General in France,

Henri Langlois of the Cinémathèque française combined his collection with Ray’s

and presented the fullest retrospective possible.

That was in February and March 1962.

Though he presented all the films in slow motion (16fps) and in dead silence,

the series was a sensation.

It led to the first batch of articles and booklets, in French, to analyse Buster’s movies.

|

|

Now that the legal path had been cleared,

Ray was free to show his entire cropped 16mm collection at the Venice Film Festival in September 1963.

“L’ età d’ oro di Buster Keaton.”

“The Golden Age of Buster Keaton.”

It was a sensation and led to the second batch of volumes, in Italian, of critical analysis of Buster’s work.

Oddly, the sensational reaction to “The Golden Years of Buster Keaton” did not result in any Italian releases.

To this day, more than 60 years later,

the only Buster silents to get official Italian reissues were The Cameraman and Spite Marriage.

Other Buster silents were occasionally shown in pirated 16mm copies, and later in pirated VHS and DVD editions,

and the Brownlow/Gill edition of The General was once shown in television, but that’s been it —

until 2023!

Buster’s silents were finally released, officially, in authorized copies, on

|

|

KirchMedia continued to reissue several more of Buster’s silents in 1962, 1963, 1964, and 1965,

only in West Germany, but then, in 1966, its affiliated distributor, Atlas Filmverleih,

went bankrupt and closed down for several years.

That stopped the series dead in its tracks.

At the same time, Buster passed away.

|

|

Back in the US, Ray showed his cropped 16mm collection at the Philadelphia Museum of Art in October 1966.

That was when Eleanor first saw most of those movies, and that is when she fell in love with them.

|

|

In 1967, Ray made some strategic arrangements with the BFI.

The evidence suggests that the BFI agreed to surrender its Buster materials to Ray,

and, in return, Ray would allow the BFI to show his entire collection on an exclusive basis.

So, in January 1968, Ray’s cropped 16mm collection,

“The Films of Buster Keaton,” played at the BFI’s National Film Theatre,

together with a few 35mm morsels borrowed from different collections.

Ray then moved this 16mm show to the Surf in San Francisco,

and then back to the BFI in August/September 1969, this time shown at the Academy One,

since the NFT was temporarily closed for remodeling.

The series returned to the Academy One on 26 March 1970 (probably in 35mm),

and it then played at the Brighton Film Theatre in July/August 1970.

The 35mm Busterfest returned to the Academy One with some regularity through 1979.

(Click here for the Academy Cinema programming, 1969 through 1979.)

|

|

The first big change came in the summer of 1970.

Or, actually, I bet it was around January 1970.

Ray tempted Ben Barenholtz of the Elgin cinema in Manhattan to front $10,000

to have 35mm prints made.

Ben had no such funds, but he somehow managed to raise (or borrow?) the money.

(I bet that Ben did not première these prints, though.

I bet the Academy One in London premièred them in March/April 1970.)

Ben’s young projectionist installed longer lenses, larger apertures,

and supplementary DC motors to drive the

|

|

Which lab made those prints, I do not know,

but those prints were reportedly gorgeous.

Gorgeous as they were, they were inauthentic,

because Ray had performed some

|

|

Well, lo and behold, I just stumbled upon a mention of an episode of “Camera Three” entitled

The Metaphysics of Buster Keaton, a little presentation by Professor Andrew Sarris,

who spent a few minutes letting Raymond Rohauer speak.

This was broadcast on Sunday morning, 1 November 1970,

shortly after the Elgin’s Buster season had closed.

For our present purposes, Sarris doesn’t matter,

and for our present purposes, Rohauer doesn’t matter.

Please click on that link and take a look at the program.

It includes an excerpt from Rohauer’s edition of Sherlock Jr.,

cropped, of course, since it was an improperly made 16mm print.

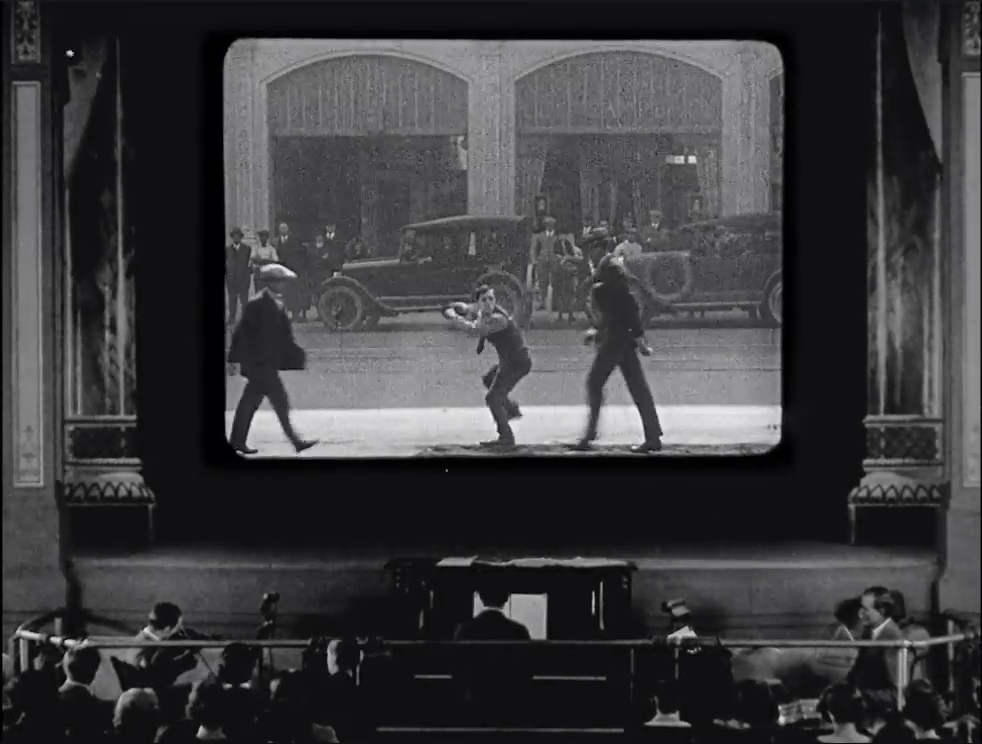

I made .GIF’s of two brief snippets, and I paralleled them with the equivalent snippets

from a later video edition. Behold:

|

1970 ROHAUER EDITION

Here we have a typical example of the needless titles

that Rohauer so commonly added to the movies he released.

As we can recognize, this is the version of the movie that Daniel Moews (pronounced Maze)

described in his book, and which he thought was authentic.

He was convinced that the authentic edition was a modernized |

1975 AND LATER EDITIONS

This is the original, which did not have any titles here.

Note that this is the domestic edition, shot with the first camera.

For the sake of argument, let us call this “Camera A.” |

1970 ROHAUER EDITION

Note that the action on the inner screen starts with the image from Camera B.

When the train appears, we see a jump in the position of the image

as we switch to the image from Camera A.

This indicates where the two variants were mistakenly pieced together.

|

1975 AND LATER EDITIONS

Oddly, the reverse happens here.

We start with the image from Camera A,

but when the train appears, we suddenly switch to the image from Camera B.

|

|

Both editions above are missing frames, but each is missing frames that are included in the other. Apparently this sequence suffered a great deal of damage. |

|

|

By the way, by calling them “Camera A” and “Camera B,” I am imposing a pattern that did not really exist. We can say that “Camera A” formed the basis of the domestic edition and that “Camera B” formed the basis for the export edition, but that was not the case at all. Buster’s crew shot with multiple cameras. The domestic edition was created not from just one camera’s footage, but was pulled from all four, indiscriminately. The export edition was pulled from the remaining footage, indiscriminately. As we can see, the negative cutter got confused and made a few mistakes. |

|

|

Here is our dilemma.

What Ray carried to the TV studio that day were 16mm copies,

and, since they were 16mm copies,

we can assume that Sherlock Jr. was the same print he had shown

at USC in February 1956 and

at the Venice Festival in September 1963 and

at the Philadelphia Museum of Art in October 1966 and

at the BFI’s National Film Theatre in January 1968 and

at the Academy One in August/September 1969 and

at the Surf in San Francisco in October 1969.

But was it?

When we flip through the pages of David Robinson’s book on Buster Keaton,

which was based on the 16mm prints shown at the NFT in January 1968,

we find nothing that would hint at rewritten titles.

That is why we assume that the prints Ray showed at the BFI NFT contained all original titles.

Yet this 16mm print that Ray brought in with him had rewritten titles!

How do we solve this riddle?

|

|

We do not have physical evidence at our disposal, and so I hesitantly offer an educated guess.

One might think that Ray took the complete prints to the TV studio,

and that the film-chain operators cued up the scenes that Sarris wanted to show.

But what if that’s not what happened?

What if Ray did not take the entire films to the TV studio?

What if Andrew Sarris simply told him which excerpts he wanted to use,

and then arranged to have the TV station pay the lab for 16mm copies of those particular scenes?

If so, then Ray would have made those excerpts from his newly revised 35mm submasters.

If so, that would explain why the cropped 16mm excerpts reflect the 1970 editions rather than the earlier editions.

Maybe?

|

|

Okay. So, so far, we know that Ray had a cropped 16mm print in early 1956, perhaps as early as the summer of 1954.

There is a possibility that he made upgrades through the end of 1969,

and there is a possibility that he made revisions, as well, over the years.

Then we know for an absolute certainty that the 35mm print he showed in September 1970 was altered.

So we know for a certainty that by September 1970, Ray had shown a minimum of two editions of the movie.

|

|

So, why did Ray copyright a new version in 1972?

Isn’t that confusing?

What could that new version have been?

Well, I think I know what it was.

Take a look below at an eBay listing from July 2024.

It is a 16mm mute (double-sprocket) Rohauer print

with Rohauer’s newly established template for titles,

namely, sans-serif typeface surrounded by a decorative border with a BK logo at the bottom.

The top and left are lopped off, once again, as this was printed through a sound gate rather than a full silent gate.

By this time, Ray knew better than to let the lab make this common mistake,

but did he have enough money in his bank account to afford to pay the lab to do a proper job?

He ordered these new titles composed to fit through a sound gate.

Zo, I think it was these new titles that allowed Ray to claim a new copyright.

Even more importantly, this seems not to have been the version that Ray had shown from 1956 through 1969.

Since he had gotten his earlier edition from Buster himself and from James Mason’s donation to AMPAS,

he had likely been showing the domestic edition.

But this 16mm print from 1972 derived from the export edition, shot mostly from a different camera.

Take a look:

|

|

I did not even attempt to bid on this.

Somebody named

autgraph listed this on eBay, item 305685785165,

“16mm Silent Buster Keaton

" Sherlock Jr " 1600 ' double sprocket

print.”

The bidding started on 21 July 2024 at $75 and the 8 bidders went to war,

ending with a snipe from a 9th bidder who got it for $291.51 on 28 July 2024.

And that is why I did not even attempt to place a bid.

|

|

|

|

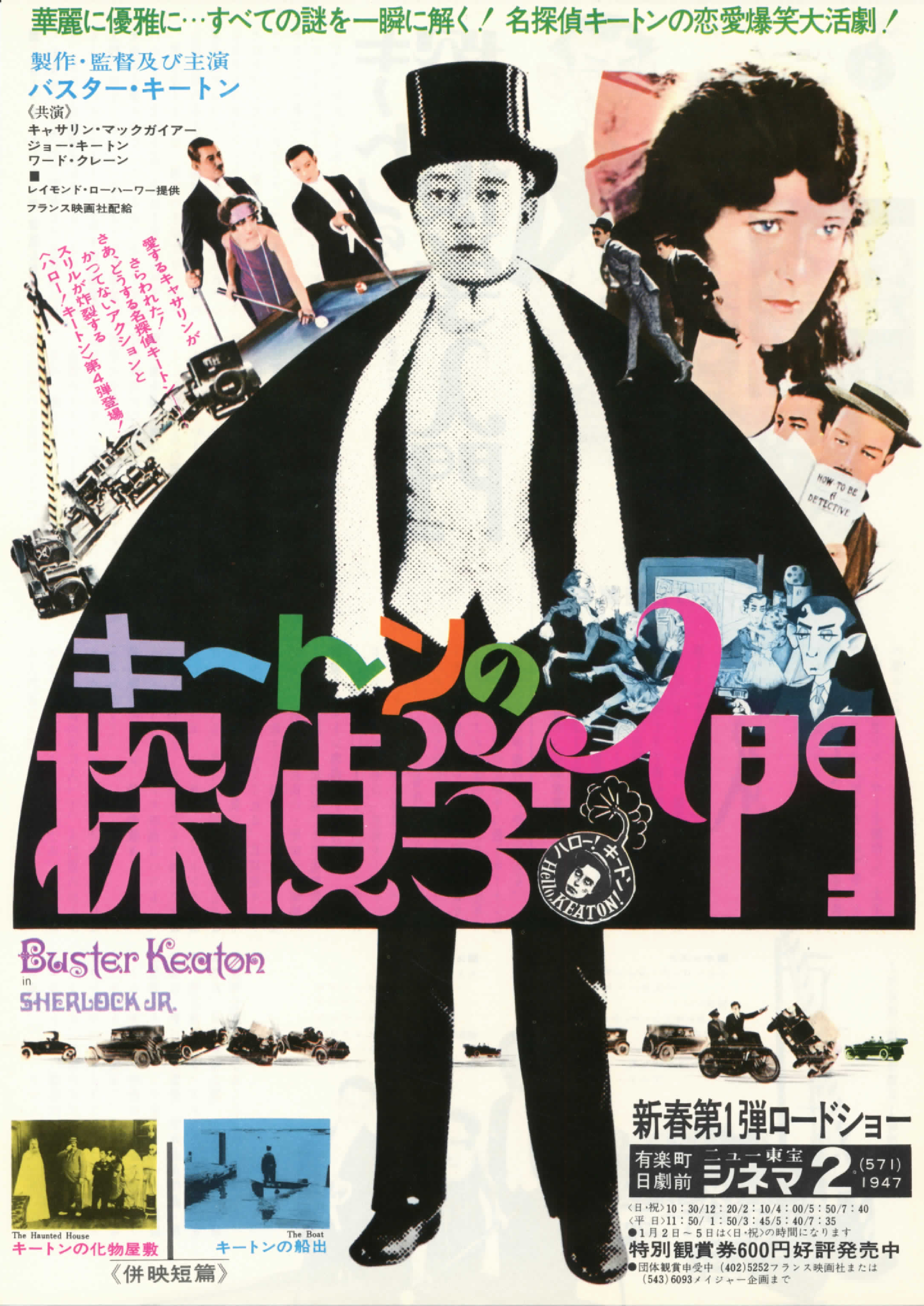

It seems it was at the end of 1973 or maybe at the very beginning of 1974 that

Rohauer licensed Sherlock Jr. to France Films in Japan

for its fourth year of a series called “Hello KEATON!”

What was the source for this edition of the movie?

How was it printed?

Was it cropped?

Fortunately, we know a tiny bit about the music.

It was a jazz score composed by Yoshimasa Kasai,

published by Hisamitsu Noguchi.

“It has been decided that this Japanese version will be the version released worldwide in the future.”

Where can I find a copy of this edition?

|

|

|

Englished:

|

|

|

Sometime around 1968, in West Germany, Atlas Filmverleih GmbH had reappeared

under a different name, Filmverleih Die Lupe GmbH (Magnifying Glass Film Distribution LLC),

which used the same logo that was still being used by Neue Filmkunst Walter Kirchner.

All three distributors were affiliated with KirchMedia and seemed to share KirchMedia’s owners.

In 1974,

Filmverleih Die Lupe licensed Sherlock Jr. from Ray Rohauer.

This was surely identical to the Japanese edition with Yoshimasa Kasai’s jazz score.

Where can I find a copy of this particular German edition?

|

|

|

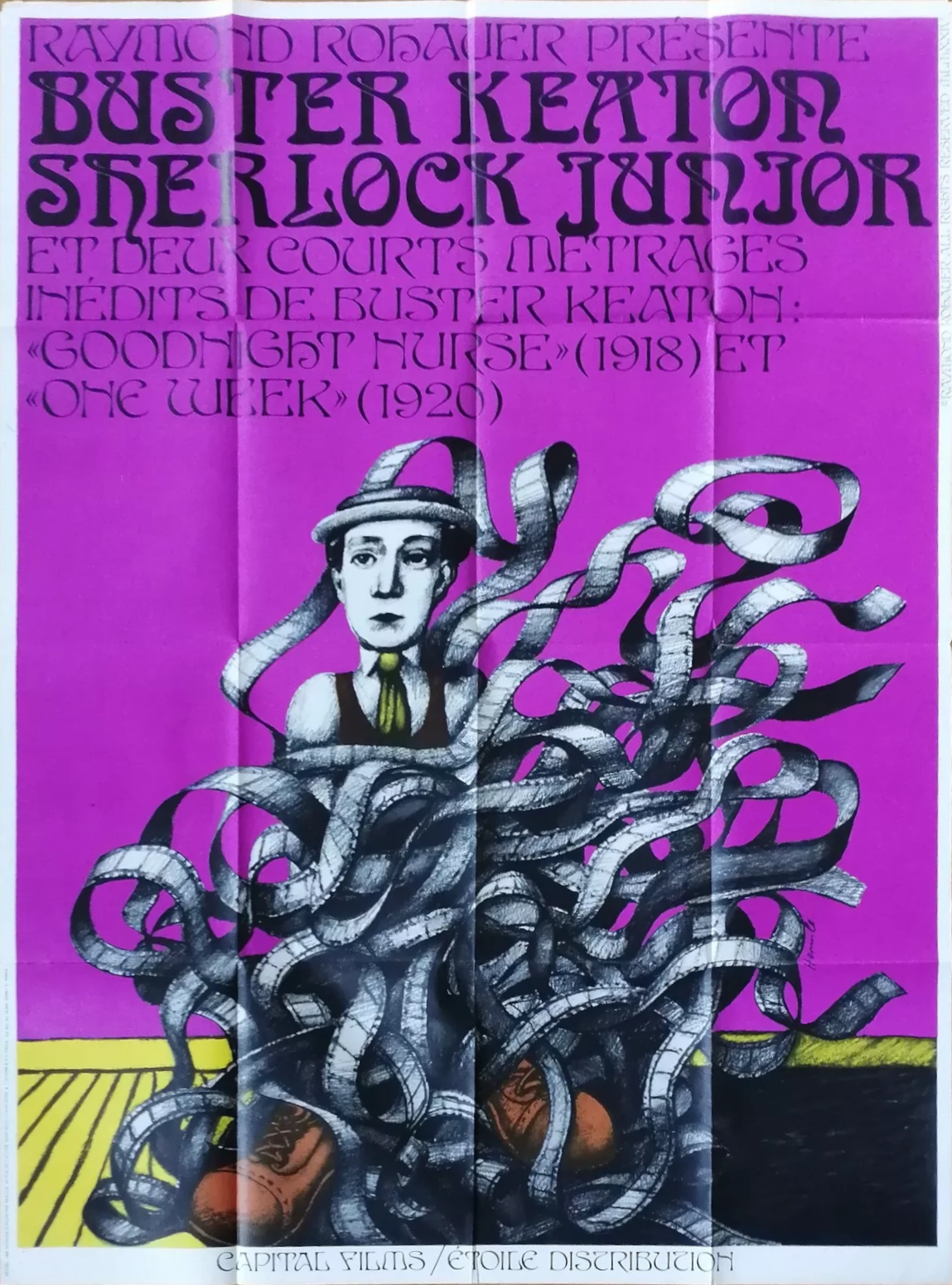

Curiously, that same year, 1974, Jacques Robert also licensed Sherlock Jr. from Ray Rohauer

and arranged to have Capital Films / Étoile Distribution release it.

This was surely identical to the Japanese release with Yoshimasa Kasai’s jazz score.

Where can I find a copy of this particular French edition?

|

|

|

Then we get to 1975.

|

|

Jay Ward Productions got access to a very scratchy print of Sherlock Jr.

Where the Ward people found this, I have not a clue.

Oh, wait, yes I do!

It was Ray Rohauer who supplied Jay Ward with a terribly scratched copy of a very nice vintage print in his collection.

I suspect that Rohauer entrusted this to Jay Ward for the purpose of creating a soundtrack.

Despite the torrential downpour of scratches, the print was remarkably sharp and nearly devoid of splices.

The Jay Ward crew instructed the lab to reduce the

|

|

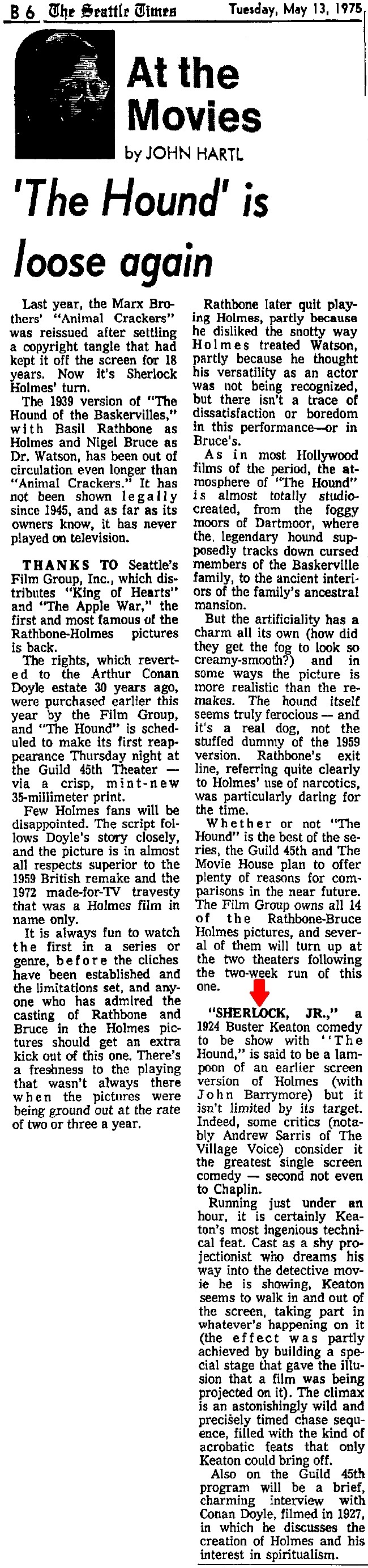

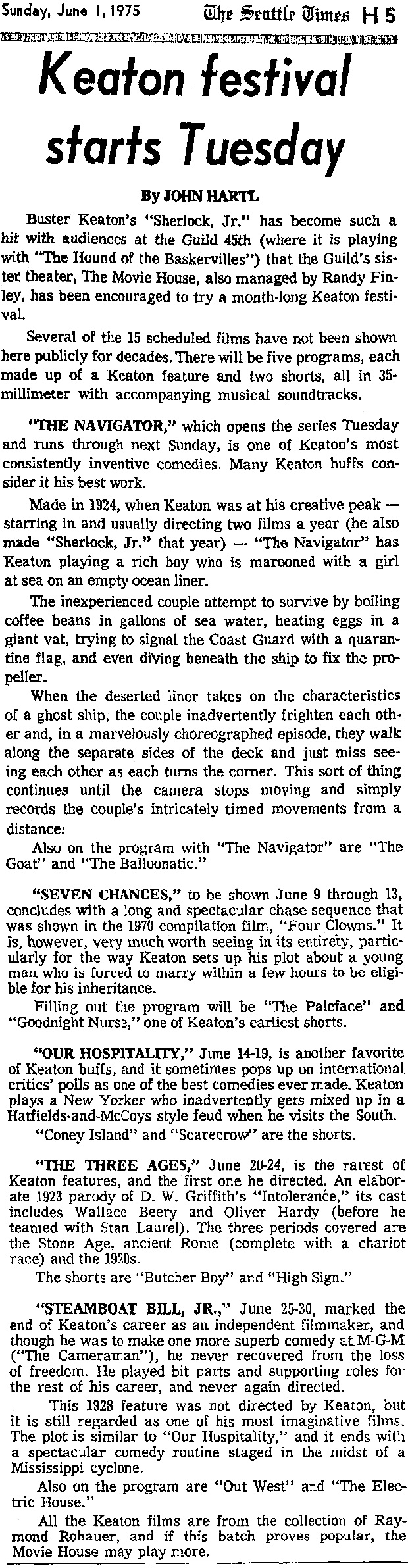

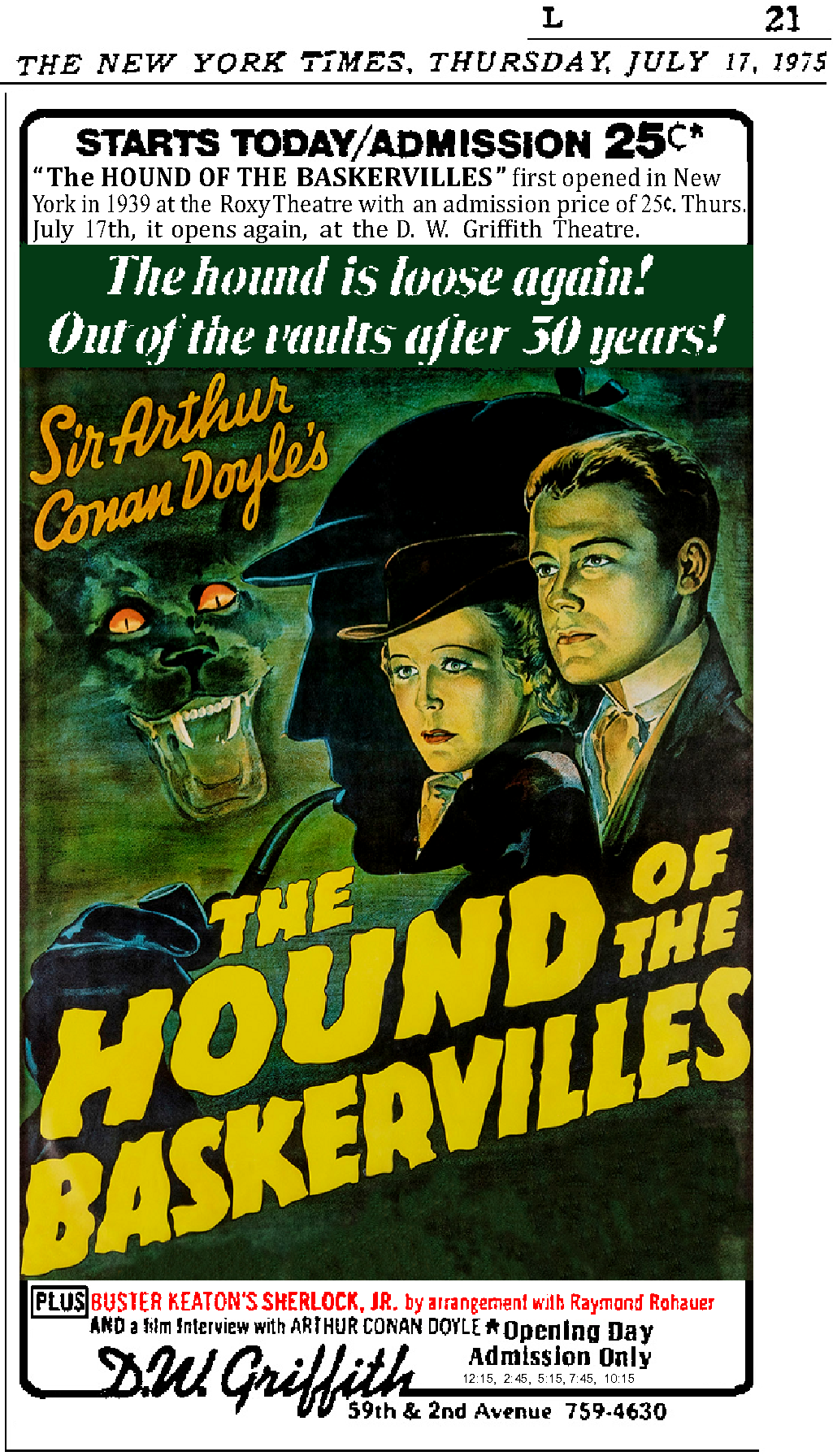

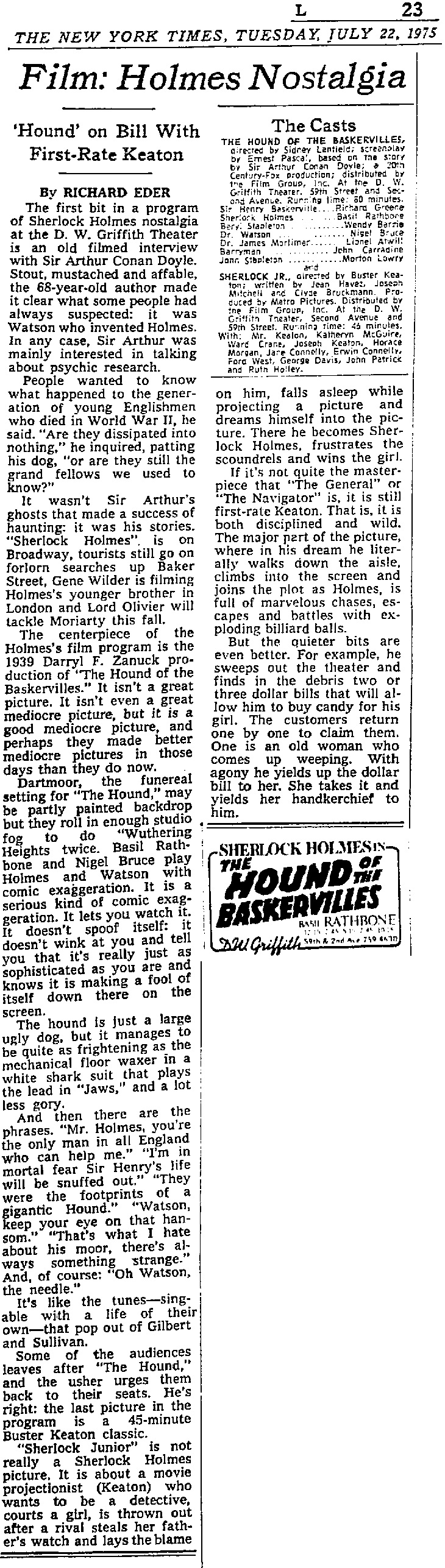

In

1973,

Randy

Finley founded a new, short-lived company, The Film Group,

soon renamed Specialty Films.

It was Randy who had been negotiating with the Arthur Conan Doyle estate for several years

to license The Hound of the Baskervilles,

and when all was agreed, the film proved to be unusable.

The negative had vanished and the several surviving prints were fragmentary.

They had to be pieced back together.

When the jigsaw puzzle was reassembled and when the rights were cleared,

Randy opened it at his Guild 45th in Seattle on Thursday, 15 May 1975,

where it ran eight weeks, accompanied by a 1927 Fox Movietone

|

|

When I put this information down in writing, a narrative suggests itself.

My guess is that Randy wanted to release not a single film, but a handsome package.

He had probably seen a 16mm MoMA print of Sherlock Jr. at a film society or maybe in college.

He probably sniffed around for the rights holder and found Ray.

Ray already had a soundtrack on Sherlock Jr., the jazz score by Yoshimasa Kasai.

For some reason, perhaps contractual stipulations, perhaps concern about quality,

Ray decided to create a different score.

To do this, he turned to Jay Ward,

whose crew had created a nice soundtrack for The General five years earlier.

|

|

Zo, I wonder why Ray supplied Jay Ward with a terribly scratched modern copy

rather than the nice nitrate from which it derived.

Was that done in error?

For reasons that I cannot even imagine,

Jay Ward and his crew got no onscreen credit at all on Sherlock Jr.,

and neither did Ray Rohauer,

though print ads revealed,

“By special arrangement with Raymond Rohauer” —

or Ruhauer as one misspelled ad proclaimed.

One thing is certain: Ward and Rohauer partnered on this particular venture.

|

|

Then the Sherlock Holmes Society of Portland presented a

benefit screening of The Hound of the Baskervilles

at Randy’s cinema, The Movie House, on

Sunday, 1 June 1975.

The beneficiary was the Burnside Community Council.

The film, together with the Movietone reel and the BK featurette, began its regular commercial run on

Thursday, 12 June 1975.

|

|

Randy ordered 28 prints.

He ordered some posters, too, but only for The Hound of the Baskervilles,

without a mention of Sherlock Jr. anywhere.

As far as I can determine, those posters were exact duplicates of the original 1939 posters.

After his Seattle and Portland bookings at his own cinemas, he began to offer the package to other houses.

Some cinemas did not book the full program, but only one or two pieces of it.

Here’s what I can find:

|

| Thu 15 May 1975 | Seattle, WA | Guild 45th | 56 days | doubled with BK Festival | |

| |||||

| |||||

| |||||

| Thu 12 Jun 1975 | Portland, OR | Movie House Theatre | 13 days | ||

| |||||

| |||||

| Wed 25 Jun 1975 | Berkeley, CA | United Artists Cinema 3 | 7 days | ||

| Wed 01 Jul 1975 | Beverly Hills, CA | Music Hall | 35 days | ||

| |||||

| |||||

| Wed 09 Jul 1975 | Minneapolis, MN | St. Louis Park | 28 days | review | |

| |||||

| Thu 17 Jul 1975 | Manhattan NY | D.W. Griffith | 14 days | ||

Don McGregor in his booklet, Buster: The Early Years, tells of his own conversion at the opening-day screening,

though he gets the date off by a year:

| |||||

¿Interesting, que no? Ran through Wednesday, 6 August 1975 | |||||

| Wed 23 Jul 1975 | San Francisco, CA | Metro II | 7 days | ||

| Wed 23 Jul 1975 | Portland, OR | The Guild | 8 days | ||

| Fri 25 Jul 1975 | Washington, DC | K-B MacArthur | 42 days | ||

| |||||

| Fri 25 Jul 1975 | Chicago, IL | Playboy | 21 days | ||

| Wed 06 Aug 1975 | Philadelphia, PA | New World | 14 days | review, mini-review | |

| |||||

| Wed 06 Aug 1975 | Philadelphia, PA | Budco Bryn Mawr | 14 days | replaced by The Railrodder on 20 Aug 1975 | |

| Fri 08 Aug 1975 | Charlotte, NC | Charlottetown Cinema II | 14 days | review | |

| |||||

| Fri 08 Aug 1975 | Columbus, OH | World | 42 days | review | |

| |||||

| Wed 20 Aug 1975 | Boston, MA | Sonny & Eddy’s Exeter St. | 21 days | review | |

| |||||

| Fri 22 Aug 1975 | Indianapolis, IN | Glendale IV | 21 days | review | |

| |||||

| Fri 29 Aug 1975 | Jonesboro, GA | Arrowhead | 5 days | ||

| Fri 29 Aug 1975 | Atlanta, GA | Storey’s Rhodes | 21 days | ||

|

|

Atlanta, GA |

|

0 days | CANCELED | |

| Wed 10 Sep 1975 | Milwaukee, WI | Downer Prestige | 25 days | ||

| Fri 12 Sep 1975 | Memphis, TN | UA Southbrook 4, scr 1 | 14 days | ||

| Fri 12 Sep 1975 | Memphis, TN | Raleigh Springs Mall Cinema II | 14 days | ||

| Wed 17 Sep 1975 | Boston, MA | Sonny & Eddy’s Allston 1 | 7 days | ||

| Wed 17 Sep 1975 | Madison, WI | Orpheum | 9 days | syndicated review | |

| |||||

| Wed 17 Sep 1975 | Santa Cruz, CA | Sash Mill Cinema | 7 days | Not with Hound, but with Adventures of SH | |

| Fri 19 Sep 1975 | Memphis, TN | GCC Plaza, scr. 2 | 7 days | ||

| Wed 24 Sep 1975 | Arcata, CA | Minor | 4 days | also as kiddie matinée w/ Silent Running | |

| Thu 25 Sep 1975 | Madison, WI | University Square Four, scr. 1 | 7 days | ||

| Wed 08 Oct 1975 | Uniondale, NY | Mime Cinema | 7 days | ||

| Fri 17 Oct 1975 | Erie, PA | Cinema World | 11 days | ||

| Fri 17 Oct 1975 | Terre Haute, IN | GCC Honey Creek Square Cinema I | 7 days | ||

| Fri 17 Oct 1975 | Salina KS | Vogue | 7 days | ||

| Wed 22 Oct 1975 | Pasadena, CA | Hastings | 7 days | ||

| Wed 22 Oct 1975 | Los Ángeles, CA | UA Cinema Center 1 | 7 days | ||

| Wed 22 Oct 1975 | Cerritos, CA | UA Los Cerritos Mall Cinemas 1 | 7 days | ||

| Wed 22 Oct 1975 | Hollywood, CA | Egyptian 3 | 7 days | ||

| Wed 22 Oct 1975 | Marina del Rey, CA | UA Cinema | 7 days | ||

| Wed 22 Oct 1975 | Torrance, CA | UA Del Amo | 7 days | ||

| Wed 22 Oct 1975 | Costa Mesa, CA | UA South Coast Plaza Cinemas 3, scr. 2 | 7 days | ||

| Wed 22 Oct 1975 | Northridge, CA | Cinema Center | 7 days | ||

| Wed 22 Oct 1975 | Redondo, CA | Marina Cinema | 7 days | ||

| Wed 22 Oct 1975 | Riverside, CA | UA Cinema | 7 days | ||

| Thu 06 Nov 1975 | Venice, CA | Fox Venice | 1 day | ||

| Wed 12 Nov 1975 | Winston-Salem, NC | Janus III | 4 days | ||

| Fri 14 Nov 1975 | Louisville, KY | Alpha 3 | 12 days | review | |

CONGRATULATIONS, WILLIAM MOOTZ! You are probably the only movie critic anywhere in the world at any time who ever noticed this ubiquitous problem. | |||||

| Fri 14 Nov 1975 | Little Rock, AR | UA Four | 12 days | ||

| Fri 14 Nov 1975 | Santa Mónica, CA | Nuart | 1 day | ||

| Fri 14 Nov 1975 | Fort Walton Beach, FL | Palm | 7 days | ||

| Wed 26 Nov 1975 | Port Jefferson, NY | Port Jefferson Twin Mini-East | 7 days | ||

| Fri 02 Jan 1976 | Cleveland, OH | Heights | 7 days | ||

|

When I first saw Sherlock Jr., it was Jay Ward’s edition,

doubled with Jay Ward’s edition of The General.

That was at The Guild in Albuquerque.

Did The General and Sherlock Jr. constitute a common double bill?

Were the two movies traveling together as a package?

No, not exactly.

I can find only two bookings for that double bill:

|

|

No. Not sent out as a package. The Loft booked a double feature in Tucson,

and so The Guild booked the same two flicks before they would be returned to whatever exchange.

Probably got a cut rate.

And, in the meantime, The Guild made mincemeat of both movies by cropping them at 1:1.66U .497"×.800",

and misframed to boot.

Not just a little misframed. Oh no. Outrageously misframed.

For Sherlock Jr., only the top of the image in some reels and only the bottom of the image in other reels.

For The General, the projectionists cranked the framing knob all the way

until the bottom of the image lined up with the bottom screen masking,

and so they showed us only the bottom half of the image.

For Sherlock Jr., they tried to center the image but overdid it.

Sherlock Jr., of course; was originally five reels, but for the 1975 reissue it was mounted onto three larger reels.

For the first two of the three reels,

I could see the projectionists, each time, turn the framing knob up and down

until they thought they had reached the middle, but they totally bungled it and got it all the way up or all the way down.

(My unreliable memory is that on those occasions when they showed only the top of the image,

even then Buster was partly cropped off the top of the moving freight train.

When they showed only the bottom of the image, of course, Buster was invisible.

There were two projectionists those two days.

Tink Luxford did the nighttime shows, if memory serves,

and some young guy, whose name escapes me and who lasted there probably no more than a few weeks,

ran the matinées, if memory serves.)

I remember that, for one screening (Sunday matinée, I think),

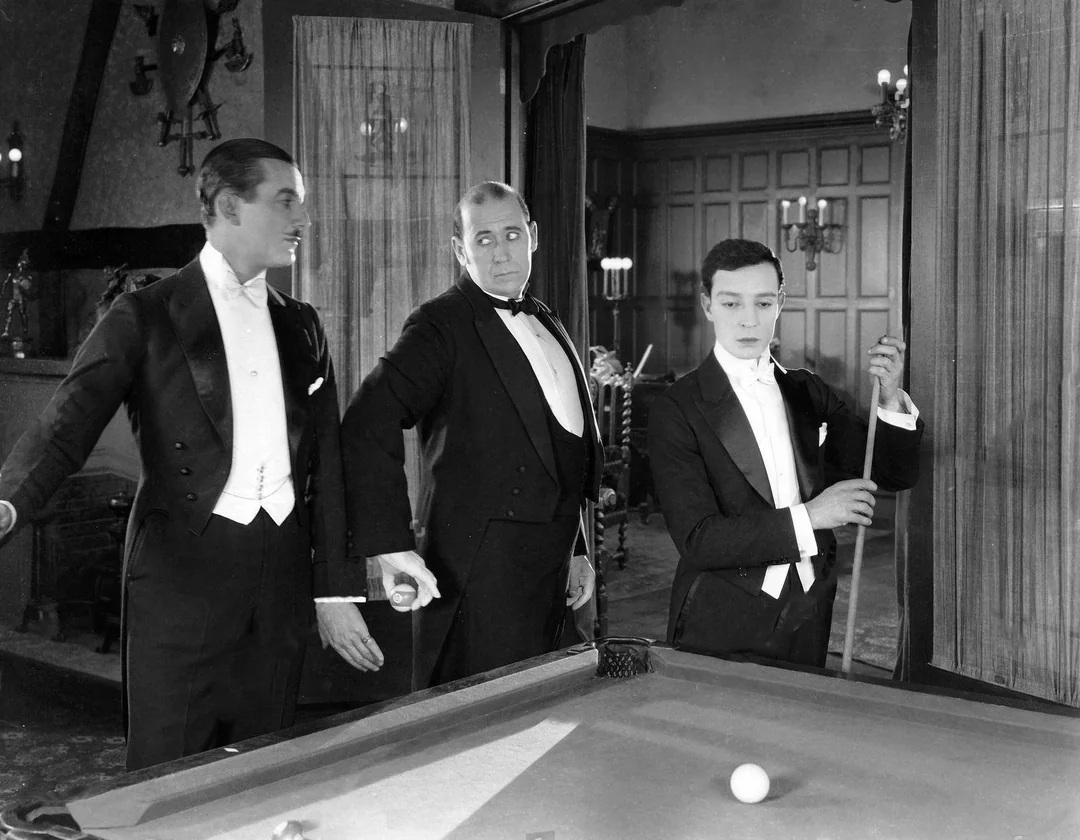

the projectionist completely cropped off the billiards game!

At that same screening, when Buster swept the garbage on the sidewalk, the pile of garbage was entirely missing!

Now, courtesy of Handbrake, I tested a video edition of Sherlock Jr. at 1:1.85,

and, as horrendous as the result looks,

as much as it would make you want to scream, you can still follow all the action from beginning to end.

It is a brutally unpleasant experience, as you will discover below, but you can still follow the story.

When it was projected at The Guild, you absolutely could NOT follow the story. Impossible.

The framing was too far off.

The three or four other people at each showing were bored and irritated, unable to follow what was happening on (or off) screen,

and simply concluded that these were rotten movies.

To say the very least, the owners of The Guild could never have competed against Werner Schwier.

Werner knew the art of ballyhoo and he could attract hundreds of thousands of people,

while The Guild was lucky if it could sell ten tickets on a Saturday together with a bucket of popcorn.

The Guild and its sister cinema made some profit for a while just by announcing movies and opening the doors,

but business could have been stratospheric if only they had employed ballyhoo.

I tried to explain, but all I got in response were facial expressions exhibiting exasperation.

|

|

The scratchy image of the Jay Ward edition

was matched to scratchy 78rpm

|

|

Clarence Williams,

Long, Deep and Wide

(Broadway (9) – 1347, 1928)

Fletcher Henderson, Houston Blues (Columbia – 164-D, 1924) Fletcher Henderson, Muscle Shoals Blues (Columbia – 164-D, 1924) Fletcher Henderson, That’s Georgia (Columbia – 202-D, 1924) The Georgians, Mindin’ My Bus’ness (Columbia – 102-D, 1924) Kansas City Five, Louisville Blues (Ajax (6) – 17072, 1925) Perry Bradford’s Jazz Phools, Hoola Boola Dance (Paramount – 20309, 1924) The Georgians, Doodle Doo Doo (Columbia – 142-D, 1924) The Georgians, Savannah (Columbia – 142-D, 1924) The Georgians, My Best Girl (Columbia – 252-D, 1925) Fletcher Henderson, Naughty Man (Columbia – 249-D, 1925) The Chicagoans, Chicago Blues (feat. The Bucktown Five) (Gennett – 5418, 1924) Bix Beiderbecke, Really a Pain (Gennett – 5419, 1924) The Bucktown Five, Hot Mittens (Gennett – 5518, 1924) Fletcher Henderson, Feelin’ the Way I Do (Silvertone – 3023, 1924) |

|

This makes me super-curious.

Why was not Joe Siracusa commissioned to add vintage mood music to the film?

Why, instead, did someone on the Jay Ward crew opt merely to add

|

|

Bill and Skip, again, did not windowbox the result.

Why?

That might be because they tested the result and discovered that,

if framed exactly at center, audiences would be able to follow the story and the action,

even though, admittedly, the images looked HORRIBLE when cropped, and I mean HORRIBLE.

I can assure you that some cinemas did not get the framing exactly at the center,

and that rendered the film incomprehensible.

Another possibility is that Randy saw no need, since he was confident that “art houses”

and repertory houses surely used the Academy format appropriately.

If that’s what he thought, then little did he know.

Never. Never. Never. Never. Never. Never.

Never. Never. Never. Never. Never. Never.

Never. Never. Never. Never. Never. Never.

Never. Never. Never. Never. Never. Never. Never.

|

|

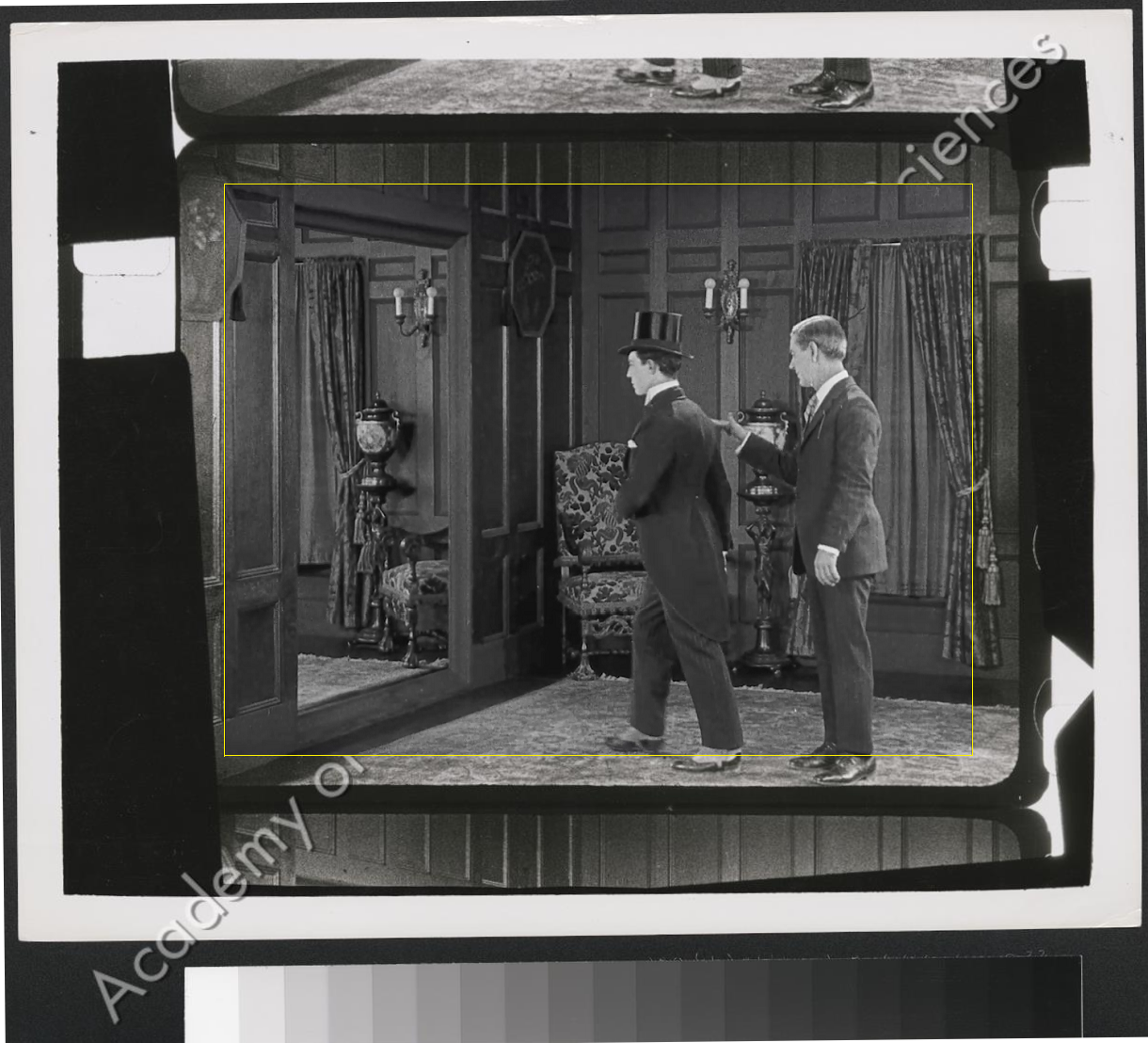

Let us perform an experiment.

At the Margaret Herrick Library is a photo enlargement of a single frame of a full-aperture dupe of Sherlock Jr.

|

|

The height of the image on the film is .723" or very close to that. Very close. Very very very close.

If, for the sake of argument, we accept that the height is .723", then the width is something like .951".

A properly calibrated silent projector would crop this .723"×.951" image

to .6796"×.90625", but don’t worry about that.

|

|

I do not know which lab made the prints in 1975, nor do I know who hired the lab.

Was it Jay Ward?

Was it Raymond Rohauer?

Was it Randy Finley?

I don’t know.

For the sake of argument, let us assume that the lab optically reduced the width to .864".

If the lab did that, then the resulting height of the reduced image would have been .657",

which was rather taller than the Academy standard of .620",

which properly calibrated projectors would have cropped to .600"×.825".

If that’s what happened, that would explain why some height was noticeably missing.

A ha!

I suspect that the .657" was cropped to .620" in the printer.

For the sake of argument, let us assume that the optically reduced image was indeed .657"×.864.

Standard US widescreen in the 1970’s was .446"×.825",

and that would put the top and bottom crop right about here:

|

So that is how much height would have been lopped off at US cinemas when Jay Ward and Randy Finley reissued the movie in 1975. For now, I am not concerned about the standard cropping of the width, since it was within acceptable parameters. |

|

Let us do a little more.

Let us find this frame on the Kino

|

Kino K679 |

|

Now let us do an overlay, so that you can see exactly how the Kino K679

|

Ouch! That is a LOT of cropping! |

|

Now let us add black borders to the left and right of the Kino K679 video to indicate how much of the width is missing.

Then let us lop off the top and bottom to match the standard .446" crop used in the 1970’s.

That is how we can discover, more or less, what audiences saw in 1975 and 1976,

assuming that every projectionist exactly centered the image,

which is a baseless assumption:

|

If the above does not display,

download it.

|

|

From 1965 through 1982, I meticulously maintained all my schoolpapers in notebooks.

All my notes, all my assignments, all the teachers’ handouts, everything.

There were precious items in there, including autographs from George Fischbeck!

Then, one day when I wasn’t looking, dear old daddy put it all out for garbage collection.

All that survived, accidentally, were a few pieces of paper.

So, absent that evidence, I shall never be able to reconstruct when I saw a 16mm print

of Sherlock Jr. at the University of New Mexico.

Ira Jaffe showed it in his film-history class.

That must have been in Fall 1979, or, much less likely, Fall 1980, but I can’t get any more exact than that,

and Ira did not keep his records, darn it!

I never enrolled in his class, but I did visit his office to pick up his syllabi every semester.

When something interesting happened along, and when I had a spare dollar (rare) and the time (rarer),

I would pay my way in and have some fun.

One day he showed Sherlock Jr. in the SUB screening room,

and so I attended with a friend who was enrolled that semester.

My memory played tricks on me.

I assumed that it was from the same source that I had seen at The Guild,

though it was mysteriously missing one of my favorite moments,

when Sherlock hits a billiard ball with his cue and it travels in a

|

SOME COPIES |

OTHER COPIES |

Things like this drive me to distraction, to fury, and I end up screaming out the window and kicking the walls.

People in showbiz, though, when these faults are pointed out to them, pretty much invariably respond, “Who cares?”

| |

|

Rohauer revived his Buster Keaton Festival in NYC at the Lincoln Plaza Cinema

from 12 August through 19 September 1981.

The show opened with the Jay Ward edition of Sherlock Jr.,

doubled with Jay Ward’s collection of Three Comedies! (or Three Shorts?)

|

|

It must have been immediately afterwards that Rohauer retired the earlier editions

to replace them with a new edition.

For his new 1981 edition, Ray Rohauer assigned Lee Erwin to improvise a score.

The film lab optically reduced the image to the Academy format and mixed in Erwin’s music.

This edition retained the remade titles from 1972, the ones with the fancy borders and the BK logo at the bottom.

The

|

|

On Sunday, 4 March 1990, I saw the movie again in 35mm at Shea’s Buffalo.

By this time Rohauer had passed away.

His successor was Alan Twyman.

The print was Academy format and projected that way, surprise surprise surprise.

The titles were all original.

It was not as scratchy as the 1975 edition.

As I feared, that marvelous

|

|

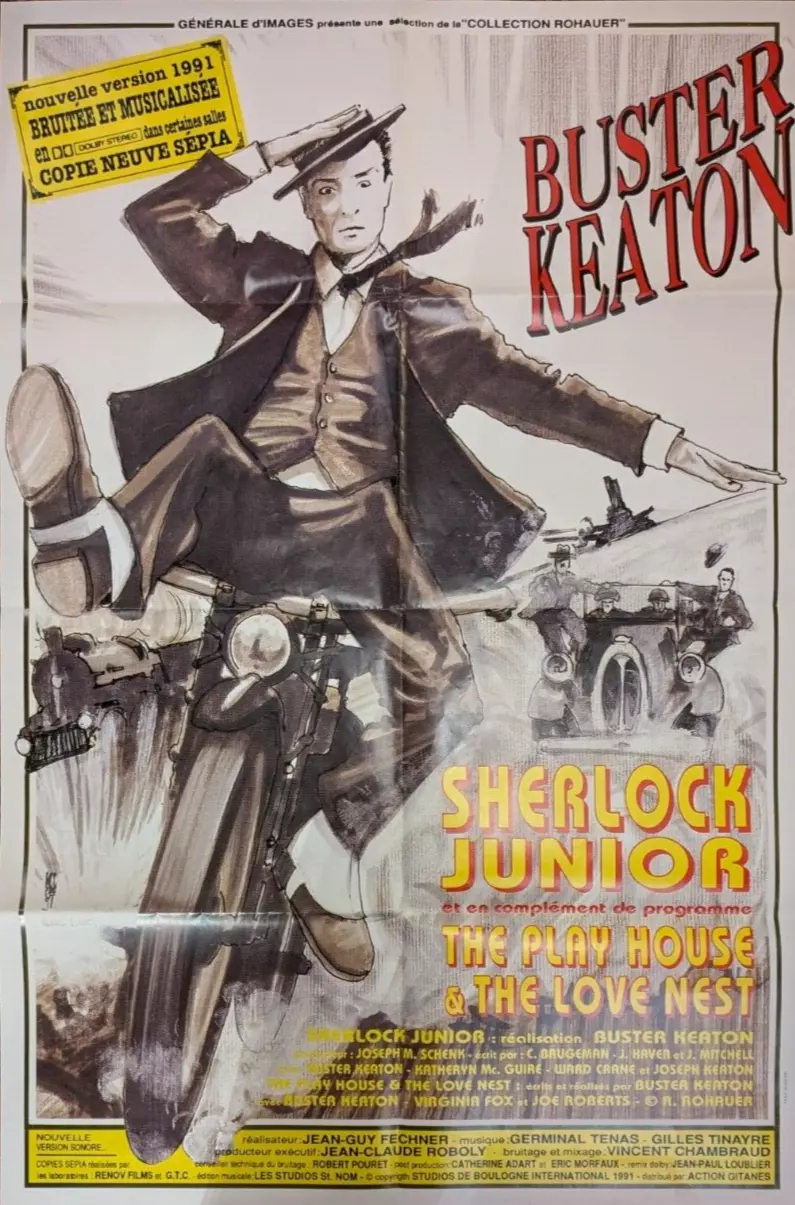

This next one I have never seen, and I have no idea where to find a copy.

In 1991, Générale d’Images issued a sepia-tinted edition in France,

with sound effects and a new music score.

Has anybody seen this?

What edition was it?

What was it printed from?

Was it printed properly or was it cropped?

What was the quality?

|

|

|

Sometime around 1992, I guess, I met Alex Bartosh who ran a tiny video shop in the middle of nowhere, Sanborn, NY.

He had a bunch of underground VHS copies of Buster’s movies and so and I bought some.

Where he got them from, I do not know.

I purchased Sherlock Jr. and took it home in some excitement.

To my dismay, it was missing the

|

|

By this time, I began to wonder if I had ever really seen that

|

|

You will notice that some copies of Sherlock Jr.

show Buster entering the auditorium at the beginning of Reel 3.

In other copies, such as the Jay Ward edition, Reel 3 opens without Buster anywhere,

but then there is a jump in the action and he suddenly pops in.

So it is clear that a source print had been shattered at the beginning of Reel 3.

Rohauer’s 1981 edition was missing the

|

|

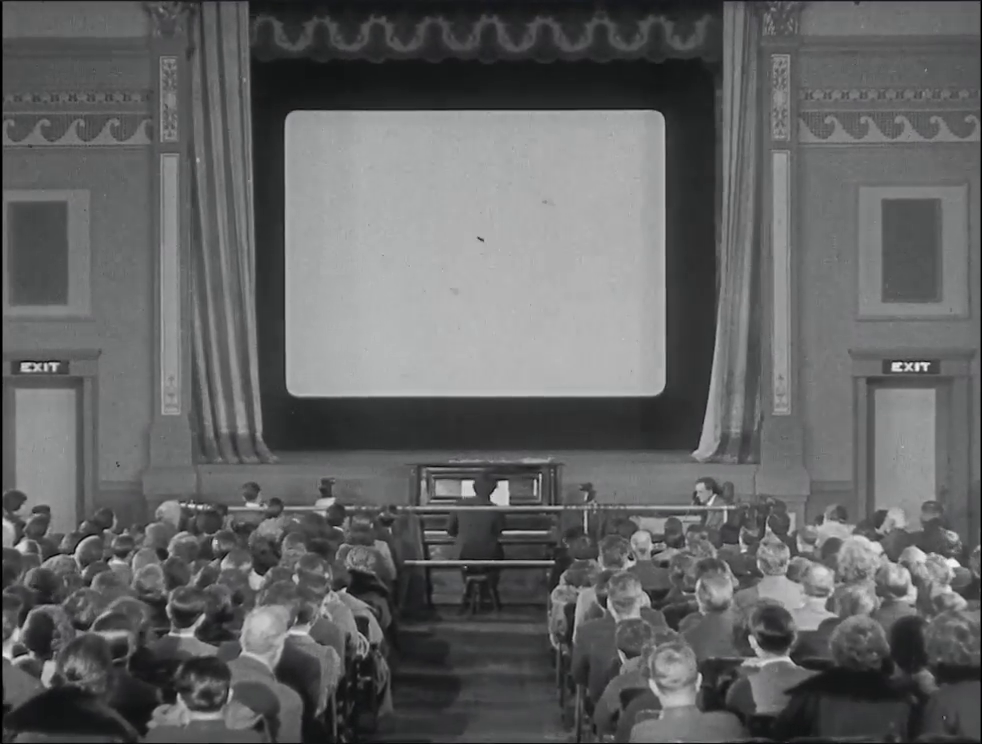

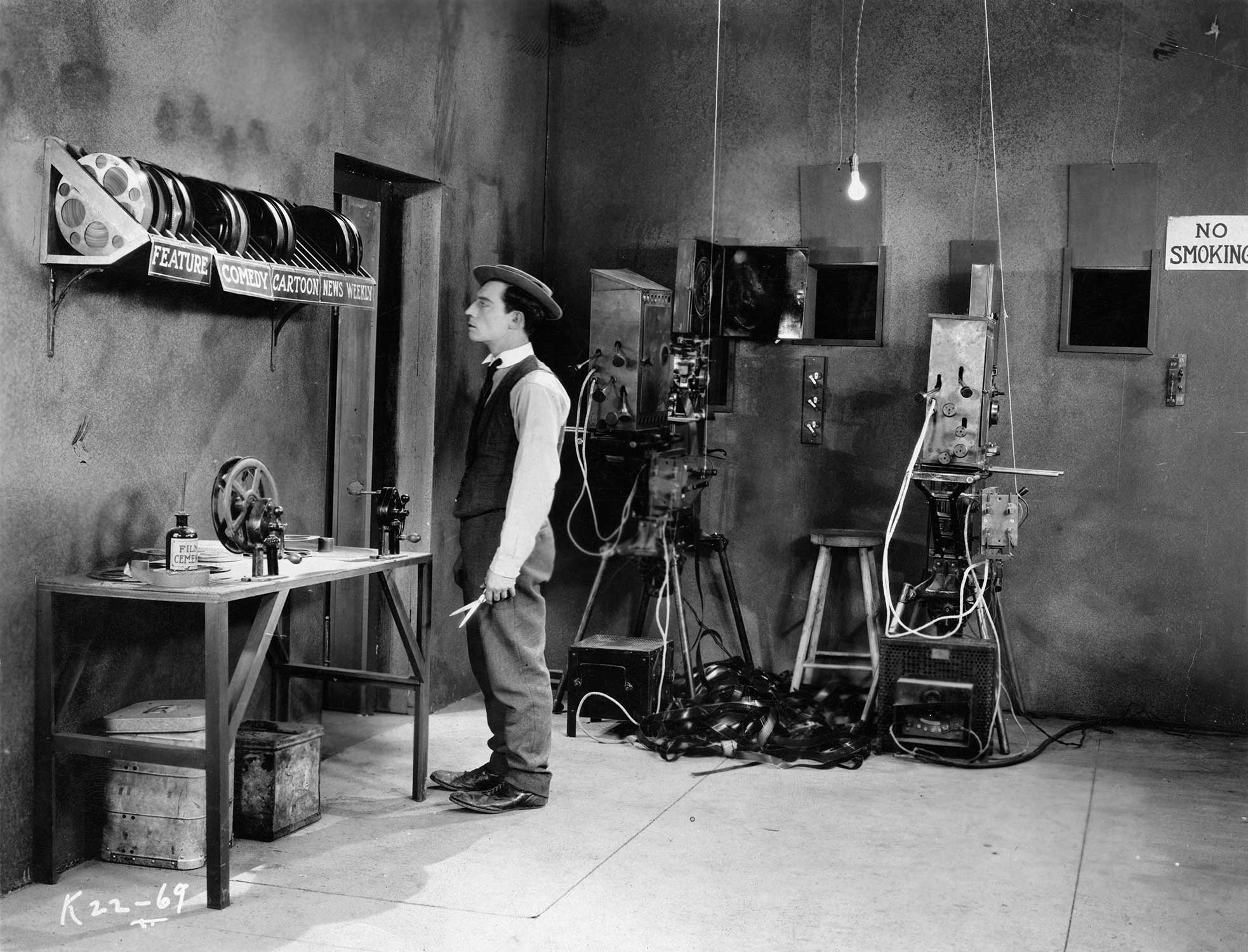

Daniel Moews, “Chapter 4: Sherlock Junior: The Fantasizing of Reality,”

Keaton: The Silent Features Close Up

(Berkeley, Los Ángeles, London: University of California Press, 1977), p. 86:

...the boy starts projecting

the afternoon’s film, Hearts and Pearls or The Lounge Lizard’s Lost

Love. Possibly because it is a Veronal Pictures production, Veronal

being a popular but dangerous soporific of the period (two younger

sisters of the novelist Ivy Compton-Burnett committed suicide by

taking overdoses), he soon tires of it and yawns. A title states, “A

projectionist’s job is tedious . . . and the monotony makes him fall

asleep.” Soon, “he dreams.”

|

|

Daniel Moews, “Bibliographical and Filmographical Comments,”

Keaton: The Silent Features Close Up (Berkeley,

Los Ángeles, London: University of California Press, 1977), pp. 327–328:

In a

The criminals having been disposed of with a grenade, Sherlock

Junior and the girl continue to race along in their car. Then she says,

in a title, “Oh, we forgot Gillette. Shouldn’t we go back for him?”

In the Audio-Brandon print, there follows some awkwardly edited

action. In the shot immediately after the title, Sherlock continues to

drive. There is then a cut to a new shot as he approaches a curve and

slams on his brakes. The awkwardness is caused by a visual

ambiguity in the action, an uncertainty whether his slamming on the

brakes is a response to the girl’s question and signals an intention to

turn around, or whether he has ignored her and is simply responding

to the curve. Since the car chassis detaches and flies over the curve

and into the water, the uncertainty is quickly obliterated in laughter.

In the

My opinion about such editing as this is mixed. Since it may have

been recently done, after Keaton’s death, it could be considered a

violation of the integrity of his work. But then, it also seems reasonable.

The cuts were minimal, discreet, and sensibly managed; the

awkward action described might have resulted from damage to whatever

surviving print lies behind present ones rather than from original

intention; and with the titles removed, the film does have a more

modern and therefore more accessible look to it, even a more Keatonesque

look (critics, including this one, have perhaps too often

applauded Keaton’s ability to construct long action sequences that

need and use no titles). The editing could also be compared to the

handling of an early book in which dated spelling and punctuation

(and also occasional misprints) are apt to be silently changed by

modern editors to conform to present usage. And if such changes help

preserve the film as a viable one, one that is more likely to be

accepted, watched, and enjoyed by present-day audiences, they are

to be encouraged. But then again, part of the charm of Sherlock

Junior, it seems to me, is its deliberately casual, deliberately primitive

look. To

|

|

We have two clips from the 1970 edition (derived from the export edition),

and we can see, obviously, that the two extra titles are Rohauer extras, not part of the original film.

Not only are they needless and in a different font,

they are not in a dialect that Buster would have used:

“projectionist” would have been “operator”;

“tedious” would have been “dull,” maybe;

“monotony” he would not have used at all;

“fall asleep” would have been “dreamed”;

but really now, Buster would never have inserted such pointless titles.

They do nothing to help; rather, they hinder the action, which is quite clear without words.

Besides, note that in the parallel edition, there are no splices

where the titles were inserted in the 1970 Rohauer edition.

That’s the dead giveaway that the titles were not in the original 1924 edition of the film.

|

|

The clumsy and primitive editing is not something I have had an opportunity to witness,

since I have not been able to find a copy of Rohauer’s 1970 edition,

but my educated guess is that the

“casual jump cuts and raggedly joined pieces of action”

were also the work of The Raymond Himself and were not leftovers from the original film.

Extra frames during those rought spots?

I doubt it.

If there are any extra frames in Rohauer’s 1970 edition,

it is highly unlikely that they might be ragged cuts where Buster removed sequences from his workprint.

If they are, then it would be invaluable to locate this edition

so that we can study the small remains of what Buster deleted.

My educated guess, though, is that Buster never made ragged cuts, not even to workprints.

What I would really love to get, though, is something nobody will ever find, because it was destroyed a century ago;

namely, the three preview prints.

|

|

Why do some copies have the

|

|

Zo, I was quite accustomed to Jay Ward’s edition,

even though I had no idea it was Jay Ward’s edition.

Jay Ward’s name was nowhere on it.

I was also familiar with one particular version from the Rohauer Collection, which I had seen in both 16mm and 35mm.

Then David Shepard and Kino issued Volume One of “The Art of Buster Keaton”

on Wednesday, 1 February 1995, and I knew that David used a different source.

My vague memory is that he told the press that he had found this edition in France.

My vague memory is that he told the press that he did not use any Rohauer/Ward source for this movie.

Methinks my vague memory is wrong, for he most certainly sourced a Rohauer print, and that is beyond any doubt.

Anyway, as soon as I saw what was on my TV screen, my jaw dropped to the floor.

Let’s start by looking once again at a more common edition:

|

|

|

|

Now let’s look at David Shepard’s edition for “The Art of Buster Keaton” from February 1995:

|

|

|

|

I was flabbergasted. Immediately.

And what flabbergasted me even more was that NOBODY ELSE COULD SEE ANY DIFFERENCE!!!!!!!!!

|

|

|

So, the lab that made one of the common editions,

similar to the Rohauer and Jay Ward editions,

captured much of the width, perhaps all of it, but not all of the height.

What we see on video corresponds exactly to my memories of what I saw in 16mm and 35mm.

The lab that David Shepard hired captured the entire image,

but then David lopped off the sides and the bottom.

Why?

There was a reason he did that.

We’ll get to that soon.

|

|

When I watched David Shepard’s video of Sherlock Jr., I had a sinking feeling.

I knew, I just knew, that the

|

|

So why did David crop off the left, right, and bottom (and sometimes top)?

There was a mistake in the domestic and export negatives back in 1924.

When Buster finds himself in the desert and jumps out of the way to avoid an oncoming train,

there is a jump to a second train.

Buster had apparently shot this scene twice, once with a short train and once with a longer one.

Instead of using just one take or the other, he cannibalized both to create a hybrid.

I have no clue why he did that.

But pay attention.

When the film splices from the first train to the second, the entire theatre building jumps,

because we had been watching the domestic edition —

until the second train appeared.

The negative cutter mistakenly cut to the export edition to show the second train.

The domestic camera and the export camera were a few feet apart and aimed slightly differently.

A few shots later, there is a cut back to the domestic negative.

|

|

In the export edition, the exact reverse happened.

|

|

That is why David Shepard lopped off the left and right and some of the height.

Doing so allowed him to adjust the centering to make the jump from domestic edition to export edition

and back again less noticeable.

Darn it!

I would much rather have the entire image, warts and all.

I would much prefer that modern technicians not make adjustments to compensate for a vintage editing error.

What I would really love, though, is to have modern technicians correct that vintage editing error,

to put the domestic shots together with the domestic shots,

and to put the export shots together with the export shots.

Then they could show us, in a supplement, what the originals looked like.

Dream on.

That will never happen.

All DVD and

|

|

My motto: BEWARE OF FILM RESTORATIONS!

|

|

It was in 2005 that I saw Sherlock Jr. on the big screen one last time.

That was a 35mm print at the James Bridges screening room at UCLÁ, during a series of Buster flicks.

The print seemed to be a twin of the one I had seen at Shea’s Buffalo.

The

|

|

When I saw Sherlock Jr. and The General at The Guild in April 1976,

both films were still under the control of Jay Ward.

When I saw Sherlock Jr. at UNM a few years later, it was under the control of Rohauer.

It derived from a different source.

When I saw Sherlock Jr. at Jackman Hall in 1995,

Rohauer was dead, and so someone sent out a 1975 Jay Ward print, probably in error.

By the time Kino issued its

|

|

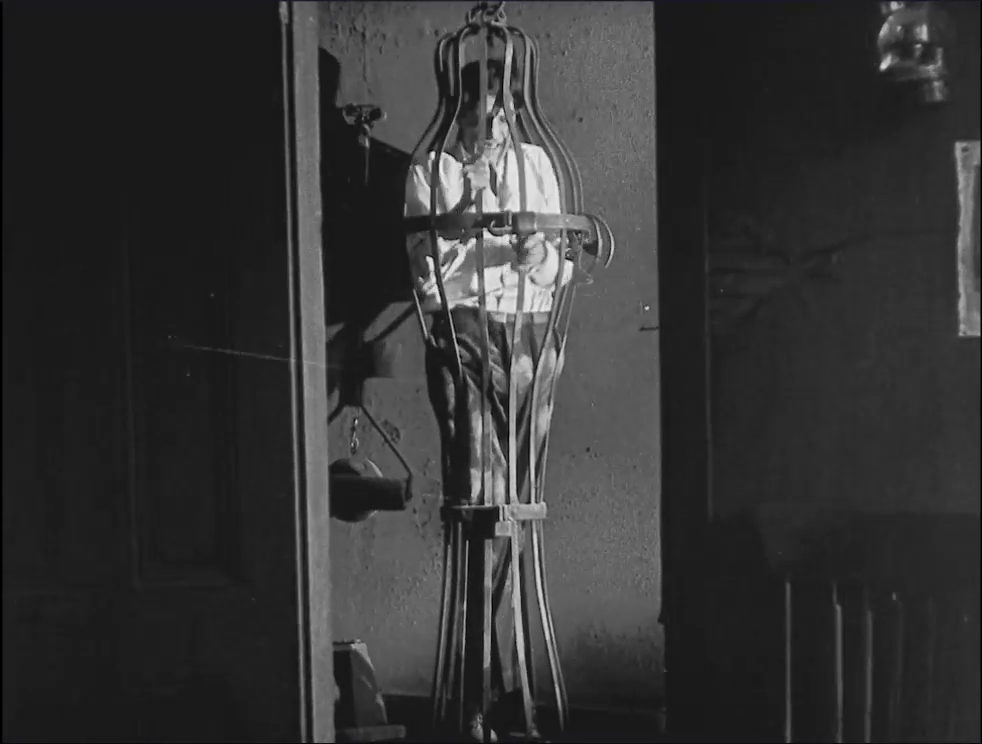

Oh, yeah, that time I saw it at Shea’s Buffalo.

I brought two acquaintances along.

There were over a thousand people in the audience, and there was screaming laughter throughout —

except from my two acquaintances.

One of them found nothing amusing about it at all.

The other, a professional magician, was mortified.

He thought that Buster was a maniac for risking his life over and over and over again, right on camera.

He found the movie horrifying, not funny.

Very odd. He was a professional magician.

He should have recognized how the illusions were done.

It was all acrobatics, magic tricks,

|

|

Oh. I remember. The print that arrived at Shea’s Buffalo had some damage.

The bit where the motorcycle hurls Buster into the shack and he inadvertently

|

|

I wish somebody could somehow dredge up the full-aperture dupe negative (or two dupe negatives?)

that Rohauer ordered at sometime between 1954 and 1970.

I also want to see his various 16mm editions.

Most of those early prints seem to have evaporated into the ether.

I want them. ALL OF THEM.

|

|

In the hope that it might be different from the other copies in my collection,

I ordered a Japanese laserdisc of Sherlock Jr., published by IVC (International Visual Corporation),

item number

|

|

Comparison time:

|

1993 German VHS, Atlas Film, 7478, 0:01:44  Japanese laserdisc, International Visual Corporation,  2005, “The Art of Buster Keaton,” Kino K123 DVD, 1:16:11  2010, Kino K679, 0:03:08  2017, Eureka “The Masters of Cinema,” EKA70269, 0:03:53  2019, eOne Cohen CMG-BD-8529, 0:03:44  2021, Lobster, EDV 1419, 0:03:07 |

|

Oh darn. I should have chosen a different frame.

No matter.

Here is enough for you to figure it out.

We should compare this shot with what we saw in the 16mm print from (presumably) 1972,

offered on eBay and which I did not even bother to bid on. Behold.

|

Atlas VHS, 1993 domestic edition |

Lobster DVD, 2021 domestic edition |

16mm Rohauer print, 1972 export edition |

|

One more comparison?

|

Export print on file at Gosfilmofond |

16mm Rohauer print, 1972 |

|

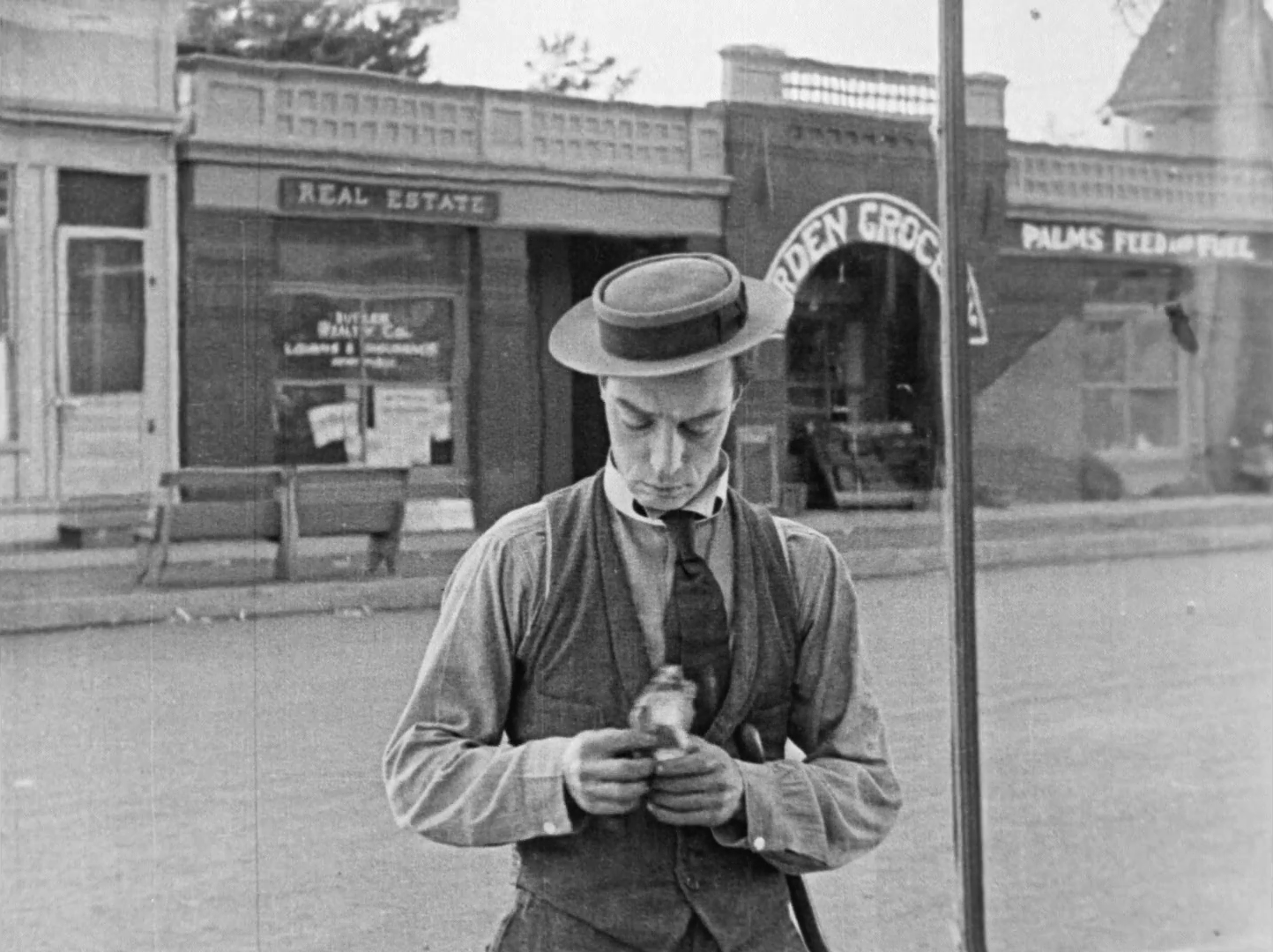

If you’re curious about it, you can Google

“Sherlock Jr.”

and see a whole bunch of unit stills of abandoned sequences.

Here’s a fascinating discussion.

Buster and his peeps, as always, used the Kodak raw stock as a scratch pad.

They changed the story multiple times and they tried scenes in different ways.

They started off with complicated situations with ridiculous ideas that stretched all credulity,

and then they finally settled on the simplest, most believable, and most direct way of telling the story.

Lots of the story ideas were completely jettisoned and characters were swapped.

When Buster finished his movie, it was six reels long, but his contract stipulated five reels max.

He had already breached that term in his previous two movies, and so for this one he didn’t dare push it.

He abridged it himself, to five very short reels, and you can see evidence of trimming from beginning to end.

He liked it this way. This was his preferred edition, and it is the only one he would release.

One loss that I regret is when he somehow knocks the reel rack off the wall.

|

|

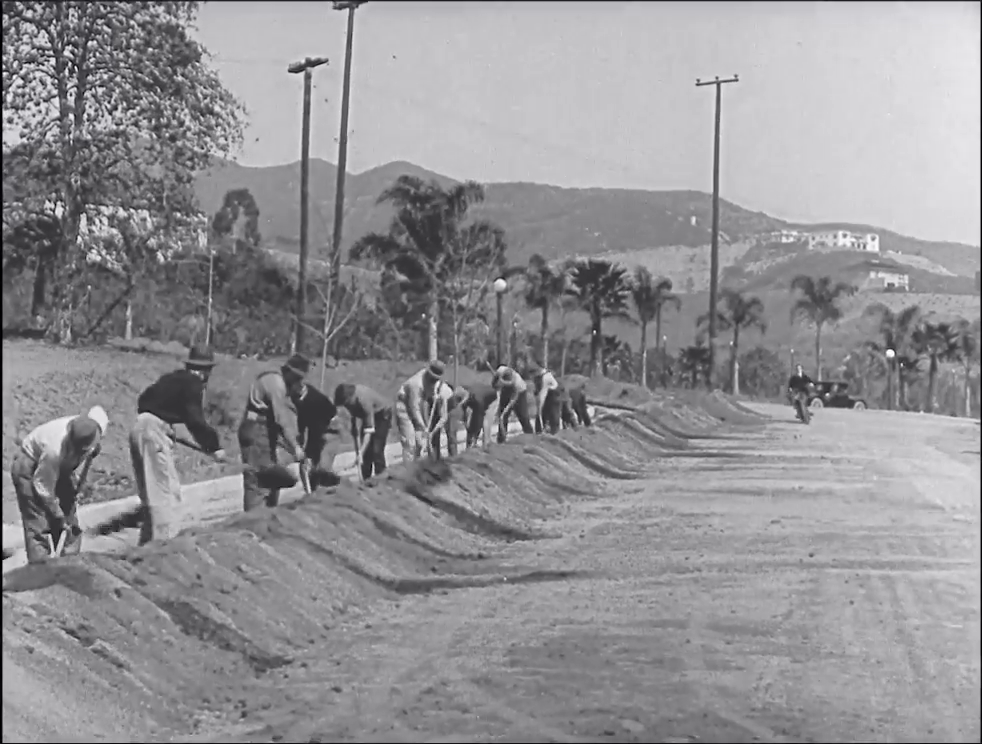

I wish somebody would identify all the extras.

|

Ford West  Probably Ann Pollard, but we’re not sure.  Doris Deane  No idea  Tom Murray  We never see his face  Joe Keaton, Jane Connelly, Erwin Connelly  Surely the locomotive’s actual fireman  Probably two of Buster’s crew members  All mysteries  No idea  No idea  No idea  Two pedestrians in the foreground, while townsfolk in the background watch the crew make a movie.  George Davis, Ward Crane, Steve Murphy, and no idea  No idea  More pedestrians  And more  And more  And more  Probably one of Buster’s crew members in drag  One of those guys is Ernie Orsatti; the others are probably Buster’s crew members  Probably crew and buddies  Another view  Probably the same buddies arranged differently  Probably the rental truck’s actual driver  The one on the left might be George Davis; the other is probably a crew member  Probably a local farmer  Same mystery couple, now with unidentified twins |

|

Kathryn McGuire’s plaid dress with all the bows and ribbons is one of the greatest costumes in movie history.

If you’re curious: Powers 6A

|

|

Sequences that Buster shot but revised or abandoned:

|

|

Buster is sweet on Kathryn McGuire.

Kathryn’s dad and his hired hand seem to be farmers and Buster seems to be their hired hand.

Buster’s rival is Ward Crane. Only the briefest flash of this sequence survives in the final film,

when we see only Kathryn and her dog.

It seems that Buster was trying to do three things at once:

Projectionist, detective, and gardener.

The still number,

Here is a fascinating photo, snapped in December 1923.

The gal in this photo, Olga Egorova assures me, is Ruth Holly.

Apparently, her scenes vanished from the movie rather early on.

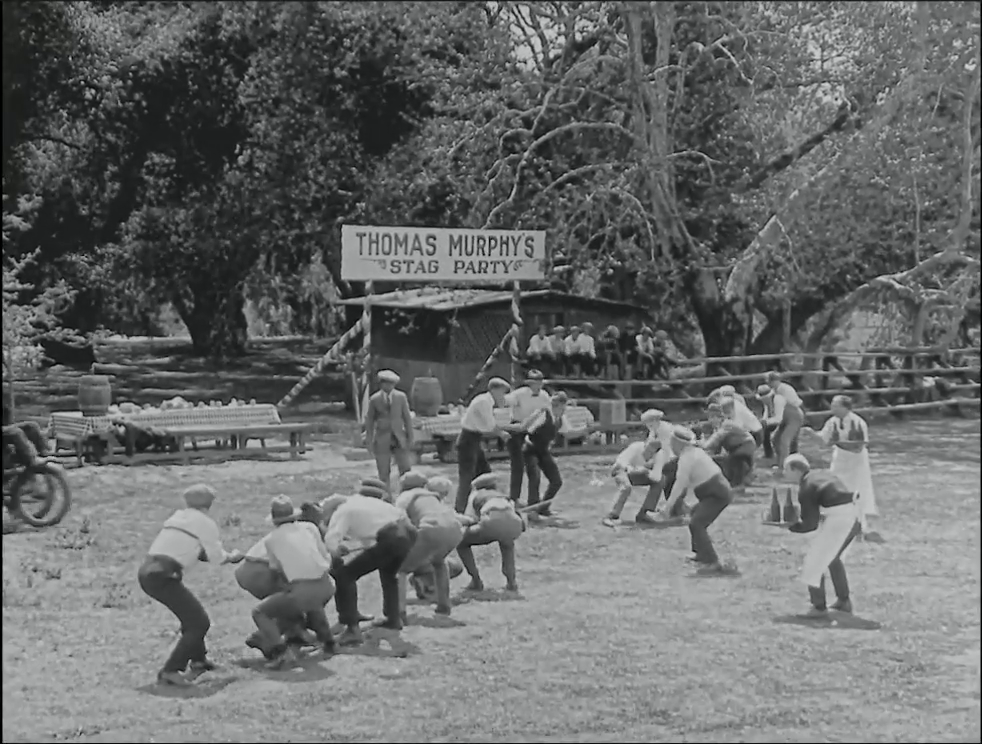

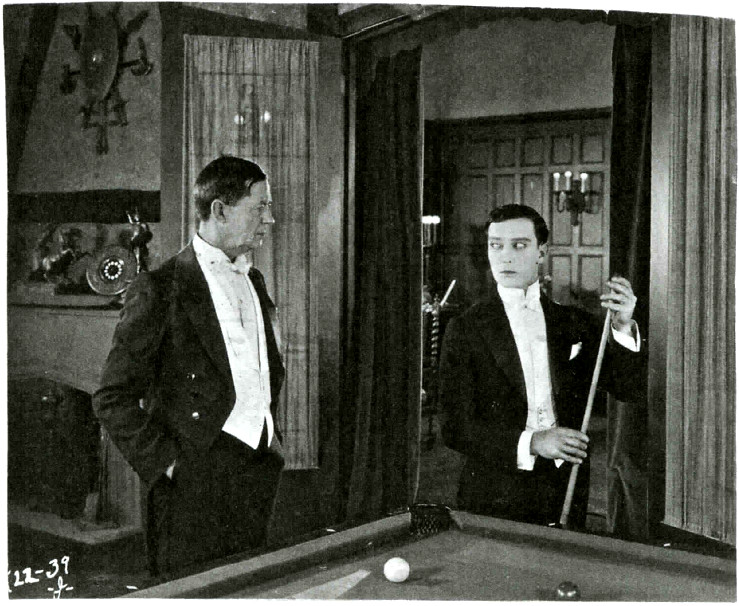

K22-6 Ann Pollard in the ticket booth. Or is it Ann Pollard? Until we settle this matter, let us just continue to call her Ann. Deal? It seems that in an early conception, Buster was so sweet on Ann that he decided to be near her by taking a job at the cinema.  Buster tries to get in at the reduced moppet rate. Viola Dana in Rouged Lips. Viola and Buster were dating off and on. But then the pressure was on to have Buster hitch up with Schenck’s sister-in-law instead. Buster got along much better with Viola.   K22-15 Buster buying a ticket just to have an excuse to say Hi to the object of his attention.  Buster has a new job, and he blocks the queue. That looks like Joe Keaton in queue, standing beside the lady who was destined to lose a dollar. Ford West is not happy about Buster getting in the way of the customers.  K22-29 New idea. Move Ann(?) out of this scene. Put her in the candy store instead. This time around, Buster is sweet on Rosalind Byrne, who works the box office. We see that The Sheik has his eye on her, too. We see that Buster notices.  K22-31 Blanche Payson is impatient at this nonsense and just wants to purchase her ticket. George Davis seems apprehensive at the potential for violence to break out.  K22-33 Ford West already knows that Ward Crane is bad news. Rosalind and Buster look on.   K22-69 Film has poured onto the booth floor. The film rack is securely mounted to the wall above the inspection bench. In the final film, we see only that the film rack has fallen down onto the inspection bench.  K22-36

K22-34 I wonder what was on that film.  K22-37  K22-35 Olga shows us what is on that film!

What is Buster looking for?  K22-64 First show is over. Time to sweep up. This is overplayed. The scene in the final film is underplayed.  K22-51 The still above and the still below are composites. The image of the auditorium had a hole cut out where the screen was, and other images were placed behind. Note that the people in the still above and in the still below have not moved a bit.

K22-57 (incomplete inscription)  K22-57 (different print, properly inscribed) The maid is Jane Connelly, Erwin’s wife in real life. They had been vaudevillians, and that was certainly how Buster got to know them and cast them.  K22-43 With a flower in his hand?  In an earlier conception, Kathryn partook in the game.  K22-39 And Joe, too?  Interesting publicity still.

K22-95 This scene was smoothed out for the final film. Ford West on the Harley, Steve Murphy on the sidewalk.

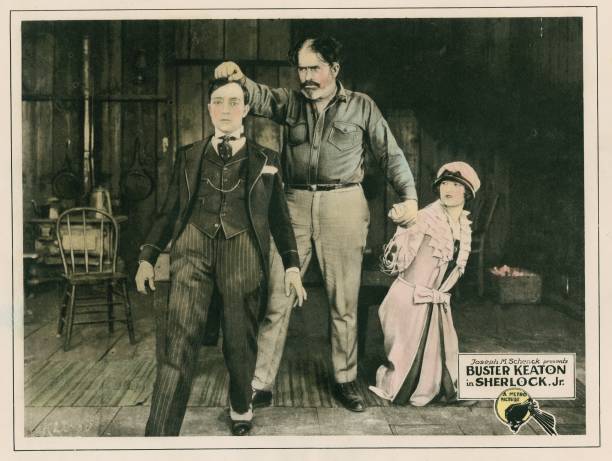

Roscoe directed the first few days, but Buster junked his footage.

This unit still was everywhere identified as Buster Keaton and Roscoe Arbuckle.

Of course!

From the moment I first saw that still, back in the 1970’s,

I instantly recognized that as Buster and Roscoe.

Not the usual cheerful Roscoe, but Roscoe in character as a menacing criminal.

Then Olga Egorova said that’s not Roscoe at all.

I was stunned.

I looked again, and it still looked to me just like Roscoe.

I lost sleep.

I looked at some Roscoe movies just now,

and I looked at the above image again, and by golly, Olga is right!

That ain’t Roscoe.

Zo, who is it?

Well, I just heard from Olga, who sent me a press release and a photo montage that she had made.

Who is it?

It’s

Kewpie Morgan, that’s who!

The guy counting the money? Who he?

I wondered since forever ago.

Then I learned what I should have recognized instantly:

He is Tom Murray!

You know, Black Larsen from The Gold Rush!

How did I not recognize him?

But that be he all right!

Wait a minute! Tom Murray. Menacing villain. Wooden cabin. Hmmmmm.   K22-81

K22-81Buster later came up with a more spectacular way to rid Kathryn of a different dastardly villain. |

|

As you can readily see from the above unit stills,

Sherlock Jr. underwent major plot and casting changes.

As usual, Buster shot more than ten times the amount of film he ended up using.

He would shoot a scene, later decide that it didn’t work,

rethink it, and shoot a replacement scene.

That happened repeatedly.

Olga Egorova wrote a marvelous investigative piece on Sherlock Jr.,

“‘Sherlock Jr.’ — The Mystery of the Script.”

(If you are curious, you can read her original Russian draft at

https://busterkeaton.ru/sherlockjr.)

She demonstrates that the film originally had an almost entirely different story.

|

|

The Margaret Herrick Library posts some images, sometimes.

Sometimes the images are there, and sometimes they are not.

That changes every few minutes, or every few days, or every few weeks.

Try your luck.

I made backup copies, just in case the links disappear again.

|

|

Now, today, a century after it was produced, the film is in the public domain,

and so it is being

tortured to death.

|

|

The Silents Synced Creator! Buster Keaton’s Sherlock Jr. X REM - A silents Synced Film, posted on Oct 14, 2024. |