Yes, Something Really Did Go Wrong

Back up! Let’s back up, because it turns out we have some clues, clues that help explain the story.

When they first began working together in 1917, Joe Schenck treated Buster wonderfully.

There was a dark side, though, that soon manifested itself.

Joe established Buster Keaton Productions in 1922 and gave Buster a 25% profit share, but no control.

Buster was a mere employee of Buster Keaton Productions.

He had no say over its management or ownership.

Buster was foolish to have accepted such an arrangement, but, like Gore Vidal in the 1970’s, he was far too trusting.

Joe Schenck might have had the best of intentions at first, but the best of intentions, in the real world, count for nothing.

Joe was married to a superstar named Norma Talmadge,

whose wallflower younger sister, Natalie, had no discernible marital prospects.

All the official narratives insist that Buster Keaton and Natalie Talmadge were genuinely in love at first,

but I have trouble believing that.

Buster thought she was kinda cute back in 1917 (she was) and he was genuinely fond of her,

and so they started dating, but only casually.

Each was probably treating the other as a placeholder pending a better candidate.

The placeholder wasn’t even holding place, since they went a couple of years without seeing each other at all.

I suspect that Joe convinced Buster to tie the knot with Natalie.

That would be, and was, a good business deal for Joe.

When reading about the courtship that led to the wedding ceremony,

one can only feel embarrassed for Natalie and Buster, and not just a little bit.

Neither was really interested in the other

and both seemed to be seeking an excuse to call the whole thing off gracefully,

without causing offense to the Talmadges or the Schencks or anyone else who may have been involved.

Marriage, though, seemed to be a good financial prospect for Natalie,

since Buster overnight became a hit with the two-reel crowd.

Enough cinemas were paying the $6 or $10 rentals that Buster was suddenly rather wealthy,

and marriage gave Natalie a piece of the pie, almost the entire pie, in fact.

Buster dreamed of a small ranch,

but Natalie had no concept of what he was talking about.

She wanted a series of mansions,

and it was those mansions, in addition to her gargantuan spending habits,

that left Buster with little for himself.

An employee in financial straits, as you know, does not make waves,

is obedient to his boss, and does not threaten to resign —

especially if said employee is married with children.

Buster was married with children.

The employee will especially not make waves if his boss is his brother-in-law.

To tender a resignation and take a job with a competitor becomes not a simple personal decision,

but veritable treachery against one’s own family.

Schenck promoted publicist Harry Brand to become manager, actually “supervisor,” of the Keaton studio —

and the definition of “supervisor” was “bean counter.”

Note that the first of these reports was dated 13 November 1926,

while The General was still being previewed,

a month before The General would be released.

Many or most reports in Moving Picture World were published weeks or even months after the events,

and so we do not know when Brand was promoted, but a reasonable guess would be sometime around September 1926,

while The General was still being edited.

Said Buster:

“But once he was in the job he suddenly turned serious.

He was grim.

He was watching the dailies — how much is spent on this, how much is spent on that?

He worries, he frets, he begins losing sleep.

He felt he had to do something, like a guy that has to tear down a car that’s running perfectly” (Blesh, p. 284).

Now that I look at the chronology, I finally understand.

Brand was commissioned to tighten the reins, but given the way Buster created his stories and directed,

there was simply no way to tighten those reins — except by not letting Buster create his stories or direct anymore.

That is not all.

The above syndicated story was published a few hours before the world première of The General.

Buster had planned to follow The General with another extravaganza called The Gay Nineties, from a story by

Robert E. Sherwood.

Nothing unusual in that.

Buster had been on friendly terms with Robert E. Sherwood since 1925.

So far, so good.

Then, eight days later, we read the punchline:

Before Buster would make The Gay Nineties, he would make something

from story ideas by Bryan Foy (one of the Seven Little Foys) and

Johnnie Grey(!).

Buster and Bryan Foy probably knew each other from vaudeville, and

Buster probably knew Johnnie Grey through Clyde Bruckman.

So there is nothing unusual in such a collaboration, but the director, chosen by Supervisor Brand, was to be

James W. Horne, whom Buster would later go on record as saying was useless to him.

Horne, as Curtis summarizes, was known for grinding out footage quickly, antipodal to Buster’s working methods.

This demonstrates that Schenck did not want Buster to direct his next picture — no more 14:1 ratios!

It may or may not be ominous that Foy and Grey would not be involved after all.

Did Schenck fire them? Did Buster fire them? Did they resign? If so, why?

Curtis claims that Foy was unable to come up with a story or gags, and that may well be right.

It is probably ominous that Schenck then pulled the plug on The Gay Nineties altogether.

Clearly, there were changes afoot, and Buster’s control over his work was being eroded, quickly.

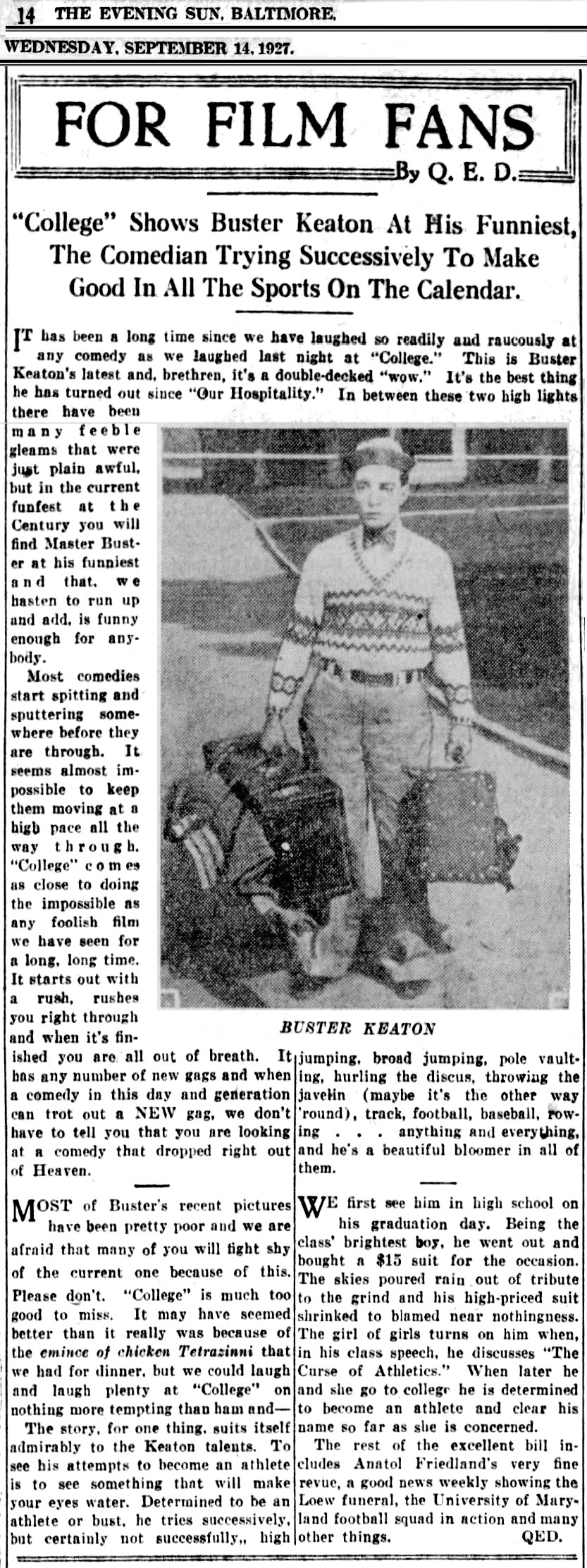

The Horne movie turned out to be College,

a cheap quickie that would rehash a recent Harold Lloyd hit called The Freshman,

and it would prove to be one of Buster’s weakest films, though it was quite profitable, even out in the sticks.

Unlike Buster’s previous stories, this one had a hissable villain,

and that was arguably a failure of imagination.

Perhaps that is why Buster later griped that his College scenarists did not understand story construction.

The Horne movie also turned out not to be a Horne movie,

since Buster grew impatient with him and unofficially took over the direction himself.

Were Schenck and Brand once again beset with a 14:1 ratio?

More or less.

According to The Washington Times, Friday, 3 June 1927, p. 12,

more than 150,000 feet of film was shot for College, which, upon completion, was about 6,000 feet long.

Since both a domestic and an export edition were created, let’s call that 12,000 feet in total.

150,000 ÷ 12,000 = 12½:1 shooting ratio.

Schenck and Brand realized, surely, that they were beset with an insubordinate star.

What had happened?

I do not know.

Nobody knows.

I can guess, though.

My guess is that United Artists told Joe Schenck in no uncertain terms that Buster,

whose wastefulness with raw stock proved his incompetence,

was no longer to direct, and that he was no longer to make expensive extravaganzas.

Before deciding what to do with the troublesome employee, the bosses would put him to the test with a quick cheapie.

That’s just a guess.

Another possibility is that Schenck hoped to cut production costs in order to allow UA to get better profits from its distribution.

An efficient director would work ten times as quickly as Buster, for a tenth the cost,

but, of course, would have results not even one-tenth as good.

Well, so much for the stories that it was the box-office failure of The General

that cost Buster his artistic freedom.

The artistic freedom was canceled before The General was even released.

United Artists bumped Buster by early October 1927, when he finished Steamboat Bill, Jr.

There was a thought about replacing him with a comic who was much less demanding.

(Charles Trowbridge? Hmmmm. Nothing to do with Buster. Nothing at all. But Charles Trowbridge????? The theatrical Trowbridges are one of my pet interests, you see. If you know anything about Charles Trowbridge, or if you are related, please contact me. Thanks!) |

Here is another article of interest,

which suggests that United Artists had a terminal conflict with Buster over Steamboat Bill, Jr.:

It could not possibly have been Schenck’s ambition to place restrictions upon Buster,

since Buster, for all his eccentricities, had been a reliable money maker for him.

The problems began within just a few months of moving Buster’s distribution contract to United Artists,

and so I draw the conclusion that it was the executive board of United Artists

that demanded an end to Buster’s unique extravagances —

shooting scenes multiple ways, stopping for baseball games whenever he was at a loss for ideas,

building a town set and then deciding to use it for a completely different purpose,

entirely neglecting the script that the accountants and executives had approved and which had served as the basis for the budget.

Those are the sorts of antics without which an artist cannot create any viable works.

Those are the sorts of antics that accountants and bosses and financial controllers cannot abide.

That this would get Buster in trouble is hardly surprising.

What is surprising is that he had been allowed to get away with it for the three years prior to being contracted to United Artists.

Technically, Buster was working for Schenck, not for UA,

but now that Schenck and UA had joined forces, the distinction between the two had dissolved.

Buster had to make the UA executives happy, whether he realized it or not, and he may not have realized it.

|

Old-time Shakespearean actor Frederick Vroom (or Frederic William Vroom) in the center.

He had been in Edwin Booth’s company and had starred with the likes of Helena Modjeska, Otis Skinner, Lawrence Barrett, Ben G. Rogers.

Major celebrities then, a meaningless list of meaningless names now. Fame is fleeting.

He apparently had some personal problems, though.

Understatement.

His transfer from stage to movies was a huge demotion.

|

The release of College was mysteriously delayed by a full season.

It proved to be a financial success.

Before it was released, Schenck allowed Buster some more leeway with his subsequent film,

a flood comedy called Steamboat Bill, Jr.

Still, though, he hired a director for Buster.

As he had done on College, Buster unofficially took over direction of Steamboat Bill, Jr., as well,

since he found the assigned director not up to the task.

Once most of Steamboat Bill, Jr., was in the can and it was time to shoot the flood climax,

Schenck suddenly grew nervous and insisted that Buster and his crew change the flood to a hurricane.

That delayed production and raised the budget by somewhat less than $35,000.

Nonetheless, the film was ready in time for its scheduled autumn 1927 release,

which would have had it compete against College.

United Artists not merely delayed Steamboat Bill, Jr., but rejected it altogether (Curtis, p. 345).

Was that retribution for Buster’s continued insubordination, as he had once again taken over direction without authorization?

Was it impatience at a project that would earn less money than other potential projects?

In the first part of 1928, United Artists backed down and reluctantly agreed to distribute the film beginning on

5 April 1928,

six months after Buster’s departure,

and we should wonder if Schenck and the trustees had put pressure on UA to do that.

The half-year delay in release delayed the film’s profits and extended its debts.

Since Buster was long gone already, and since this was initially a rejected film,

United Artists performed an experiment on it:

Instead of putting it on the market for all the Loew and Paramount/Publix and Fox deluxe houses to bid on,

UA simply released it only to its own handful of cinemas and then instantly kicked it down to the second-run neighborhood houses.

That killed most of the potential earnings.

It still made a profit, but it could have made many times more.

Also, the half-year delay was the same half-year that the Hollywood studios were all converting to sound.

It was a terrible struggle for the big studios — Warner Bros., Paramount, MGM, and the rest — to convert to sound.

They hired away every telephone and radio technician they could, built gigantic sound stages the size of modern convention centers,

and re-equipped them every month or so to have new gear replace last month’s obsolete gear.

All the different troupes had to share the same few sound stages, and time was at a premium.

In the silent days, a troupe was pretty much on its own, at its own schedule.

There was time to experiment, improvise, rehearse, revise.

If a troupe used a script, that script was hardly more than an outline or a departure point.

When every troupe had to share the same facility, though,

it had to get in, shoot its scenes quickly, and then clear out to make way for the next troupe.

Rehearsing and revising during shooting time, trying variations until the troupe got a scene or character to be satisfactory,

well, those days were over.

Once the accounting department approved a script, no changes were to be made to it whatsoever —

not a line could be changed, not a word, not an action, not a camera angle. Nothing.

Schenck was the Chairman of the Board at United Artists,

and so perhaps United Artists could have rented one of its sound stages

to Buster Keaton Productions for a few weeks each year, or perhaps for a few hours each day.

The problem was that United Artists had been in business for less than a decade

and it was only just now taking its first baby steps to establish its own cinema chain.

Its income was at the mercy of the other cinema chains, which were all owned by rival Hollywood studios.

Finances were still too tight.

My guess is that United Artists rejected the idea of allowing the Keaton Studio to use its facilities,

just as it had initially rejected Steamboat Bill, Jr.

By the way, no independent filmmaker, not even Charlie Chaplin, had the money or the pull to convert to sound

in the 1920’s or early 1930’s.

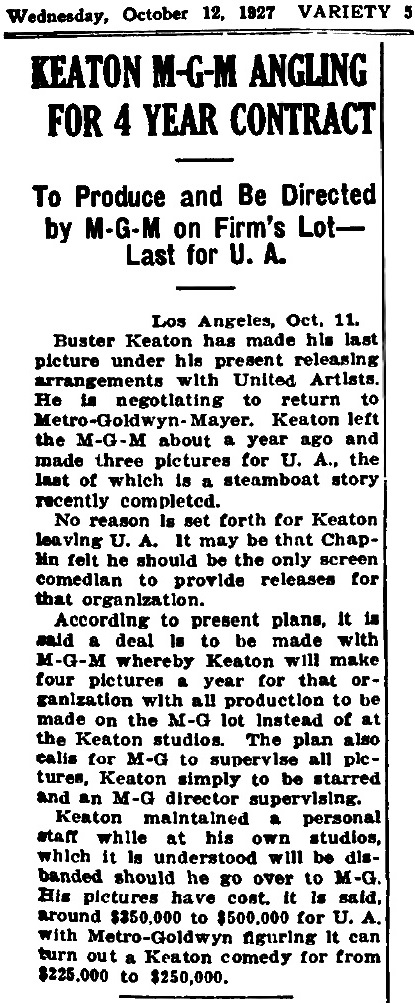

Buster’s contract had apparently been for three films to be distributed by UA.

(An article from the 12 October 1927 issue of Variety makes that pretty clear.

Keep scrolling down and you’ll get to it.)

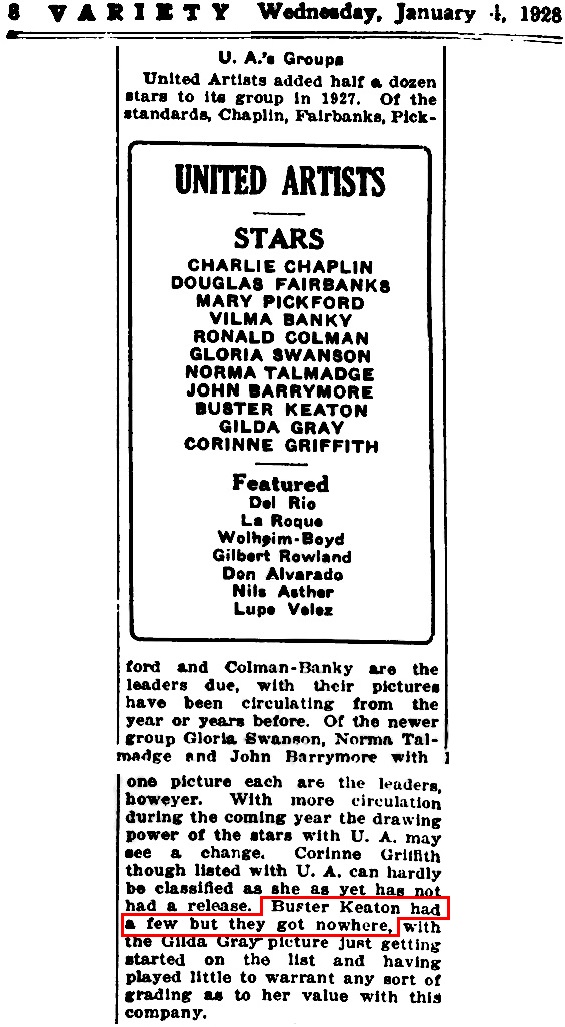

His movies, while profitable, were not the sensations that UA was hoping for.

Is that a justified assessment? I think so.

Here is a snippet from an article:

“They got nowhere”?

They made profits.

In English, “profits” is good.

In Investorese, “profits” of one penny less than an immediate 700% return is “nowhere.”

The UA execs were speaking in Investorese.

Now, I’m thinking back to Peter Krämer’s claim that UA had not invested in the production

and hence earned only a trifling amount in its rôle as distributor.

If that is true, then the UA execs simply took exception to performing such a minimal task for such a minimal return

and thus immediately tried to get out of the contract.

So many postulates, but no firm data. Infuriating.

I could continue conjecturing until the cows come home,

and I could probably come up with a dozen or more plausible narratives,

but there would be zero evidence for any of them.

All we can say for certain is that the UA execs were dissatisfied with its contract with Keaton Productions,

and they had been dissatisfied almost from the get-go .

This gives us a pretty good idea about why UA decided against renewing the Buster Keaton Productions distribution contract.

Probably — probably — influencing UA’s decision was Buster’s 14:1 ratio,

his refusal to follow the budgeted scripts, and his insubordination in taking over direction.

My guesses. Those are only my guesses.

Since UA no longer wanted the Buster Keaton Productions distribution contract,

Schenck and the other trustees sold that contract to MGM.

That happened during the filming of Steamboat Bill, Jr.,

and it happened behind Buster’s back.

The cost of converting the Buster Keaton Studio to sound would have been prohibitive,

and that is probably why the trustees decided to close the studio.

Since Buster Keaton Productions was worthless without Buster Keaton,

they sold his employment contract to MGM as well.

It was an easy sale.

Nick Schenck, Joe’s brother,

had control of MGM purchasing and he owned a goodly number of the Buster Keaton Productions shares, too.

He and the Loew boys and Friedman probably insisted upon terms that would keep Buster in line

and prevent him from improvising and directing and thus running up expenses.

Probably. Again, that’s just my guess, but what else could have happened?

|

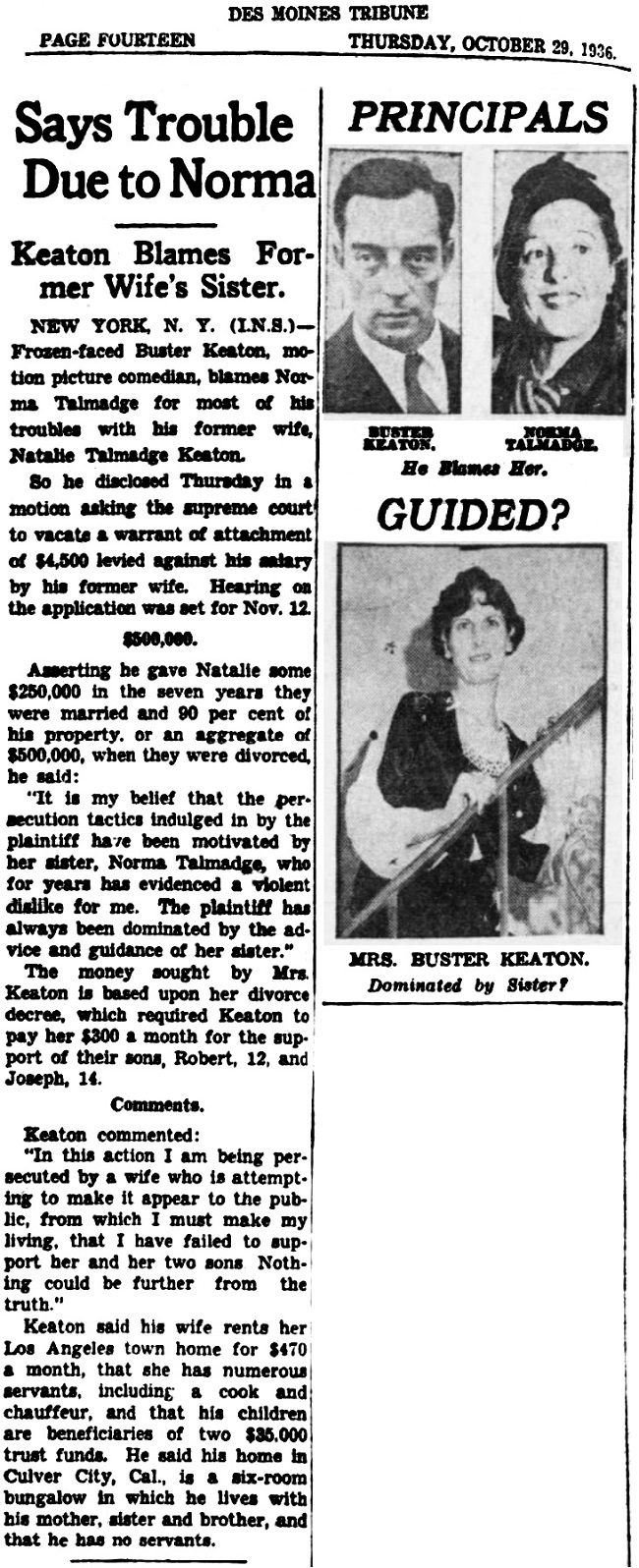

Here’s another idea.

I really don’t think this had anything to do with the trustees’ decision,

but there is a lingering suspicion in the back of mind that this may have influenced it.

Norma Talmadge, Joe Schenck’s in-name-only wife, despised Buster.

Could it have been that Schenck and the trustees initially brainstormed some ideas to allow Buster to retain his studio?

Could it have been that Norma put her foot down and said “Absolutely not”?

I really don’t think so, but still, it’s a thought.

Here is food for that thought:

To the International News Service some eight years later, Buster’s lawyer spoke on his behalf.

|

So, the trustees closed the studio and sold the contracts to MGM —

without first telling Buster.

It was a fait accompli.

Why did the trustees not involve Buster in these decisions?

Perhaps they figured that Buster would object without offering a better solution.

Perhaps they just didn’t want to hear whining from another of those troublesome artistic types.

Of course, the trustees were the employers, and Buster was a mere employee who had no say-so.

The bosses could legally do all this, and there was nothing a mere employee could legally do about it.

And anyway, since when does an employer ever consult an employee about anything?

Unheard of.

It is obvious that these movie executives, like typical movie executives, knew nothing about movies.

Buster, under someone else’s schedule,

under someone else’s direction,

under someone else’s script, is nothing special.

Under those conditions, he becomes just any other two-bit actor,

doing what any two-bit actor could do.

Movie executives didn’t understand that.

Movie executives couldn’t understand that.

It was hopelessly beyond their intellectual capacity to understand that.

In an attempt to protect their investment, they assassinated the goose that had been laying golden eggs.

The trustees’ solution to their problem would fail, and it did fail.

Not immediately.

It didn’t fail immediately.

It continued to make some good money for the trustees for five years, but then it failed, totally,

and it drove Buster to what I would describe as insanity.

Thus ended Buster’s career as a filmmaker.

Buster had never asked to be a filmmaker, he had never planned on such a career,

but once the rôle had been thrust upon him, he found that there was nothing else he enjoyed even half so much,

and he was being paid handsomely to enjoy himself.

Then, in an instant, his career was taken away from him, without warning, forever.

In his as-told-to memoir, My Wonderful World of Slapstick (pp. 201–203),

Buster takes full blame for everything.

“Against my better judgment I let Joe Schenck talk me into giving up my

own studio to make pictures at the booming Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer

lot in Culver City.”

He then tells two microscopic details of some conversations.

I wish I could have been a fly on the wall at that time.

When Schenck and the trustees closed his studio and sold his contracts,

Buster realized that he had made a terrible mistake.

Harold Lloyd and Charlie Chaplin had both seized control of their productions and film rights and had quickly become millionaires.

Buster should have done the same, but he simply trusted that the trustees had his best interests at heart.

In this account, which I suspect is not quite right, Buster asked Harold and Charlie for advice.

As far as I know, Harold and Buster were casual acquaintances, not friends.

Charlie and Buster were social acquaintances and invited each other over for barbecues and so forth,

and they occasionally traded gags.

Did Buster phone Charlie and Harold?

Did he bump into them?

Did he bring up the topic at the next Sunday barbecue?

Did he drive over and knock on their doors?

What precisely did he tell them?

What precisely did he ask them?

|

From the very start I was against making the switch to

“Don’t let them do it to you, Buster,” he said. “It’s not that they

haven’t smart showmen there. They have some of the country’s

best. But there are too many of them, and they’ll all try to tell

you how to make your comedies. It will simply be one more case

of too many cooks.”

Harold Lloyd was of the same opinion. Both Charlie and he

had retained their own units. Their pictures were first-rate and

were coining money.

|

Buster told a variation of that story to Rudi Blesh (pp. 297–298).

In this version, it was not simply that Buster asked Charlie for advice.

He did, but it was Charlie who had approached Buster when he heard the news.

|

...He sat in silence as

Joe Schenck went on. Buster was making no more pictures. No,

Schenck corrected himself, what he meant was no more Schenck-Keaton

productions. The company was being dissolved.

“Why?” Buster’s lips were dry and tight.

Schenck did not elaborate. Instead he proceeded to the next step.

Keaton was going on MGM’s payroll. Once on this topic, the older

man seemed to relax. He grew voluble: more money, bigger opportunities,

better pictures; a big staff to work for you — stories and

production, cutting and editing, everything. You can’t miss. My

brother Nick will take of you like his own son.

Buster just sat there. There seemed nothing to say in the face of

such finality. Schenck quickly outlined the plans. Buster was to start

with MGM right away. There was a settlement — Keaton remembers

it was only a few thousand dollars — for all his interests (never written

down or clarified anyway), including possible reissues of his pictures,

nineteen two-reelers and ten feature films, pictures that by all obtainable

reliable estimates must have grossed around twenty million dollars

in less than eight years. The stockholders kept the films. Keaton

was a free agent.

It was all familiar — a scene from a Keaton comedy — this conference

with his old booster and benefactor. His face went automatically

blank. He fell into his part. Not a muscle moved. But hold it! It was

life — not a movie. Buster can still recall, even today, how at that

moment his thoughts turned, as if against his own will, to a theatrical

trunk left in an alley behind a theatre. Here went the last of his Joes.

Long after the one-sided interview, Buster Keaton was puzzling

over it. He is still puzzling — and still feeling the dazing, almost physical

impact of the unexpected blow.

“So many times,” he has said, “I’ve thought it all over. Hell, I

knew I was a money-maker. And not a big spender. Why, Christ, my

pix cost a couple of hundred grand — Fairbanks couldn’t make one

under a million. It wasn’t that.

“I thought of this: Joe Schenck was still an independent. I don’t

know if it was human nature, greed, or power, but the big companies

were out to kill the independents. Motion pictures were becoming

the finest trust you ever saw. So I thought, Perhaps they’re after

Schenck. He was too big to knock down, but maybe his brother Nick

at MGM said, ‘Look, Joe, it‘s hurting the business.’ Could be. In

fact, within two more years Joe left United Artists and quit independent

production entirely. Norma and Constance didn’t succeed

in sound pix. Joe went on and became head of Twentieth Century-Fox.

But if that was his real reason, why didn’t he tell me? We were

friends.

“One thing: I had only one picture in 1927, with the delay caused

by Brand on Steamboat Bill, Jr. Also, Joe’s own United Artists

gummed up its release. Let it out only to their few theatres and took

the shine off. Then the other big theatres wouldn’t touch it, and it

went straight down to the neighborhood houses. That may easily

have cost us three-quarters of a million. But Joe Schenck was always

a reasonable man. Would he blame me for that?

“But there it was: me for Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer. Just like the

draft. Everyone seemed to know that it had happened. Chaplin said

to me, ‘What’s this I hear? Don’t do it. They’ll ruin you helping

you. They’ll warp your judgment. You’ll get tired of arguing for

things you know are right.’ I knew Charlie was leveling. Worse, I

knew he was right. Harold Lloyd said it, only in different words.

‘It’s not your gang. You’ll lose.’

|

Without knowing the full circumstances and the full conversations,

we cannot know what to make of this.

Did Charlie and Harold simply tell Buster not to go to MGM, and then blithely move on to the next appointment?

Or did they offer advice on alternative strategies?

Charlie had helped to found United Artists.

Though he had no administrative control over the company,

his word nonetheless carried some weight, and perhaps perhaps perhaps he could have convinced the executives

to buy back Buster’s contracts? Maybe? Or maybe it was too late for that?

Did either Charlie or Harold suggest that Buster buy back his own contracts and buy out shares in the production company?

Did either of them offer to assist, or refer him to legal counsel or accountants to help him avoid the abyss?

Did either of them realize that Buster could not solve his problem by mere refusal to move to MGM,

that Buster did not share their freedom to make their own decisions?

We’ll never know the answer, because none of the three spoke further of this incident to anybody.

What is evident, to me, is that Buster thought he had friends everywhere,

because he thought a large social life indicated a large number of friends.

The most telling statements in the above passage reveal that Buster literally didn’t understand what was happening.

He wondered if “they” were after Joe Schenck, because “they” wanted to put an end to the independents.

As we have seen, Schenck and the other trustees were far from independent.

They were powerful studio executives, fully owned and operated by the top Hollywood oligarchs.

Their heralding of Buster Keaton Productions as an “independent” company was nothing more than a charade,

a charade that would expire sooner or later.

Joe Schenck and the other trustees allowed Buster relatively free rein so long as it was convenient for them to do so.

The moment it was no longer convenient for them, they no longer allowed it.

Buster also wondered why Schenck did not confide business matters: “We were friends.”

Yet this “friend” had just paid him off a mere few thousand dollars

in order to buy off any of his claims to $20,000,000 worth of assets,

and did not put anything in writing.

As the saying goes, a verbal contract isn’t worth the paper it’s written on.

Buster couldn’t see that this was certainly not a demonstration of friendship.

It was cold, calculating, heartless.

Joe Schenck was definitively not a friend.

The bargaining was not done in good faith, since there was no bargaining at all, just an ultimatum.

Buster’s astonishing insight into human motivations when he created characters on screen

did not entirely translate to a similar understanding when thrown into an unexpected real-life circumstance.

It turned out he had few friends, very few, and those few friends were in no position to help.

Anyone who had the means to help simply didn’t.

A friend would have offered more than a simple admonition to “Don’t do it.”

Joe Schenck, despite all the favors he had given Buster and would continue to give, was not a friend.

The trustees were certainly not friends.

To the trustees, Buster was nothing other than a machine that generated money,

and when the machine began to generate a little less money,

they decided that it was not worth the expense to take it to the shop for a Clean-Lube-Adjust.

Instead, they sold that machine as-is to someone who was in the market for a used machine.

Simple as that. Completely impersonal.

By purchasing the Buster Keaton Productions contract and Buster’s employment contract,

Nick earned even more wrath from studio head Louis B. Mayer,

who, in addition to his countless other faults, detested comedies and comedians

and did whatever he could to make Buster’s life miserable.

Mayer could not take his vengeance out on Nick, though,

because Nick, who was with parent company Loew’s, outranked him.

Mayer privately referred to him as Nicholas Skunk.

|

There you go. No more creation. No more directing.

His troupe is disbanded.

All for a faulty cost-benefit analysis.

Yeah, and an order of burger-fries-soda is less expensive and more profitable than a curried cauliflower salad,

but if your restaurant makes that substitution on the basis of a cost-benefit analysis, you’ll lose all your customers.

|

If the trustees had decided to close the studio and sell off the company’s contract a year earlier,

Buster could easily have rounded up investors to take his productions over.

Almost any investor would have leapt at the chance.

Not anymore, though.

It was now October 1928, during the transition to sound;

the movie business was too uncertain, prices were too high, and so no investor would consider the idea.

Buster could have gone back to vaudeville, but vaudeville was now in its death throes.

Buster could have gone back to the stage, but the stage had no more call for variety comics.

Buster could have switched careers and become a mechanical engineer,

but he had that horrible mansion to pay for as well as an extravagantly expensive wife and two tiny mouths to feed.

He dared not take a cut in his income.

He applied to Paramount Pictures, but Paramount was well aware

that MGM had an exclusive contract with Buster Keaton Productions,

and nobody wanted to go to war with MGM.

He was trapped.

I wish Buster had done what Charlie Chaplin had done.

Charlie saved his money, built his own studio, founded his own production company,

funded his own movies without borrowing a cent from anybody, and kept all the profits.

When Charlie could not afford to switch to sound, he continued to make silent movies.

Because he never borrowed money,

Charlie’s movies were all dirt-cheap

and they looked dirt-cheap, but audiences ate them up all the same.

Why didn’t Buster do that?

Why didn’t Buster follow Charlie’s sterling example?

Because he had that blasted mansion to pay for

and because his wife spent every penny of the money that was left over.

That’s why.

The upside?

If Buster had followed Charlie’s footsteps, he would never have made The General.

It would have been beyond his means.

That was the upside of working for Joe Schenck.

He spent Joe’s money to make The General.

That was the upside.

That was the only upside.

That is how he got the chance to make what I think is the finest movie ever.

In a sane world, a nonexistent sane world, Buster could easily have solved his problems:

Dump the mansion, regardless of his wife’s objections, move to a small house in a normal neighborhood,

tell all the movie execs to take a hike,

take a year off, and maybe open his own little theatre somewhere.

It would have been novel enough to turn a small profit,

and performers the world over would have jumped at the opportunity to try out new material with such a renowned master.

Then he could have just let destiny take its course.

There is no sane world.

Another possible solution:

Work at MGM making lousy movies, not take them seriously, refuse to get upset,

and wait patiently two or three years for the movie business to stabilize.

Then buy out Buster Keaton Productions.

Let his MGM contract come up for renewal and renegotiate it as an independent producer rather than as a contract actor,

with an option for MGM to purchase shares of each upcoming production, and with an option to distribute.

Maybe that would have worked, or maybe not. Worth a try? I think so.

Were the BKP trustees or MGM to have informed him that BKP was not for sale,

then BK could have made P nearly worthless by choosing not to renew his contract.

Buster was in a position to play hardball, but he was so depressed and demoralized that he didn’t even notice.

Depressed and demoralized.

That was yet another problem.

According to Marion Mack, Buster had a drinking problem even as early as 1926.

We can look to outside sources for that:

Schenck problems, wife problems, mansion problems, in-law problems, family problems.

But those weren’t the reasons.

Such things are never the reasons.

The reason was on the inside.

Buster was self-medicating , but he probably did not understand that

and if somebody had explained it to him, he would have refused to listen.

He definitely needed a different life, but he lacked either the insight or the courage to make a change.

For some people alcohol is an upper, but for most people alcohol is a downer.

For Buster, it was the downest of all possible downers.

It was drowning his sorrow in alcohol-induced depression and so he adamantly refused to give it up.

To the end of his days, Buster had nothing but the nicest things to say about Joe Schenck,

and he would not countenance any dissent in that regard.

Methinks Buster never understood what had happened.

He never understood how terribly he had been manipulated.

In Joe’s defense... I can’t think of anything to say in his defense.

Well, for the first few years, Joe let Buster do pretty much anything Buster wanted to do, within budget limitations.

Buster wanted co-stars, but Joe didn’t want to spend two star salaries,

and so Buster didn’t have co-stars.

Other than that, the professional situation had been pretty nice for the first few years.

Buster’s first assignment at MGM was a dreadful script called Snap Shots.

Yes, I have read it, both drafts.

It is easily about the worst piece of junk I have ever seen;

it was so childishly awful that I felt embarrassed for the author.

Buster fought long and hard to toss out the script and improvise his own story.

He won that battle, and the result was a celebrated silent picture called The Cameraman.

MGM then dispersed his crew and assigned him standard assembly-line projects.

Most of his subsequent MGM films are now regarded as unwatchable,

but, domestically, they were rather successful, and some were surprisingly profitable.

When Buster told of that in a filmed interview,

you could hear in his voice that he was trying not to burst into tears.

The reason for the success was surely not that audiences enjoyed them more,

but that MGM had superior booking clout in the US,

since its corporate owner, Loew’s, had a large chain of deluxe cinemas.

Why were those particular MGM films profitable?

The story is that MGM/Loew’s produced, distributed, and exhibited the films

with its own studio, its own distribution arm, and its own chain of deluxe cinemas,

and thus eliminated all middle-men and essentially bypassed all competition.

Paramount did the same, but failed and soon declared bankruptcy.

When Warner Bros. found that its rivals wouldn’t book its films,

it bought out several cinema chains and in no time flat copycatted MGM and Paramount.

(One of those was the Stanley chain, operated by Moe Mark, another Buffalo boy — and not just a Buffalo boy.

Moe and his late brother Mitchy were two of the most important people in cinema history, but they are now entirely forgotten,

deliberately omitted from the history books.)

United Artists was also forced to begin the same process in order to survive, but oh my heavens could those peeps be clumsy.

MGM was in a good position, a foolproof position, a never-fail position.

Nonetheless, it is not until just recently, as I’ve been sifting through the ancient newspapers day by day,

that I see how MGM simply saturated the market like never before.

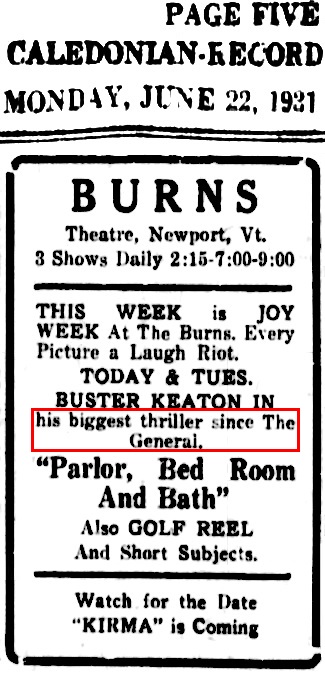

A dreary flick called Parlor, Bedroom and Bath,

an insult to the intelligence,

was simply showing everywhere, for months!

Since it hogged so much of the market, it could not help but earn a profit.

It flooded the market.

Or, better to say: It drowned the market.

Since producer, distributor, and exhibitor were effectively all the same company,

paying the moneys back and forth was just moving change from one pocket to the other.

I glanced through a random few reviews of these dreary MGM-Buster flicks,

and the reviews were sort of positive, saying, essentially,

that if you liked Buster back in his old silent days,

well, here he was again, doing more of the same; so go and have a laugh.

I got the distinct impression that the reviewers had an agreement with MGM to write only nice things.

The critics, despite signing their names or initials, sounded alike and said about the same things,

which demonstrates, at least to me, that they were basing their scribbles on a studio-prepared template.

The movies were terribly cheap and they looked terribly cheap.

Cheap can be beautiful.

Charlie Chaplin’s movies are all cheap, but visually they are astonishing and they are all made with loving care.

The MGM productions with Buster, though, did not merely look terribly cheap, they were visually dreary, total downers.

Technically they were perfect, but æsthetically they were repellent.

The movies saturated the market, quickly sucked the market dry,

and the execs lived happily ever after.

I was disheartened to see this advertisement:

MGM’s corporate point of view?

A cinch.

MGM had worked out a profitable formula and had mastered the technique of churning out feeble-minded pabulum.

It was a success. It made money for everybody.

When Nicholas Schenck hired Buster to work at MGM, he explained more than he realized he explained:

“Your studio is a little place;

our big new plant will give you bigger production,

relieve you of producing.

You just have to be funny.

We got great writers and directors out there.

The best.

Experts. Don’t worry. Be happy” (Blesh, p. 299).

Cringeworthy.

As I have been saying for half a century,

the people in charge of the movie business know nothing about the movie business.

“Hey, Botticelli, your art studio is a little place;

our big new plant will give you bigger production,

relieve you of producing.

You just have to paint by numbers.

We got great artists out there.

The best.

Experts. They’ll sketch the drafts for you.

Don’t worry. Be happy.”

MGM would never let Buster play anything like a Johnnie Gray or any of the other characters he had invented.

MGM insisted instead that he play an irritating idiot.

That’s what the MGM executives thought comedy was: a parade of irritating idiots, bumbling nitwits, crazies.

Each of those MGM starring vehicles opened with a credit boasting that this was A BUSTER KEATON PRODUCTION,

and that must have stung.

So, what’s the big deal?

Most movies are lousy and forgettable,

so if you get a job making movies, you should expect to be paid to make a lot of lousy forgettable junk.

But you get paid!

It’s like any other job.

The whole point is just to get paid, nothing else.

How many of us are thrilled to do our daily eight-to-five?

We do it because we get paid, and we don’t give a thought to our professions once the whistle blows.

In Buster’s case, though, it was different.

He put tons of love into his work, and he invented variations upon a lovable character.

Audiences who are introduced to Buster through The Boat or Our Hospitality or The General

would be most interested in seeing more.

It was that sustained interest that kept Buster employed.

Once he was dumped into such excrement as Free and Easy and Sidewalks of New York, there was a different dynamic.

Audiences introduced to Buster through those movies would have not the slightest enthusiasm about seeing him again,

as his character is entirely uninteresting.

While marketing trickery forced those films to be profitable in the short term,

those films effectively ended any possibility of Buster’s making anything remotely resembling what he had so loved making before.

That was devastating, as devastating as the murder of a loved one.

It’s like taking Monet’s brushes and canvases away and forbidding him, on pain of death,

from doing anything more elaborate than filling in coloring books with crayons but paying him very well to play with those crayons.

It’s like congratulating Paganini for his skill by breaking his fingers, but paying him very well to sing gangsta rap.

Devastating.

|

I ain’t through complainin’ ’bout Dardis.

Of all the films he was ever in, Buster hated

Sidewalks of New York most of all.

That was in 1931, during his MGM tenure.

Sidewalks of New York was not his worst movie, not by a long shot.

But it was the final straw that made Buster give up all hope.

He tried to get out of the assignment, but the bosses wouldn’t hear of it.

He could have stood up for himself, but he was what shrinks now call “conflict-avoidant,”

and the bosses took full advantage of that trait.

He dreaded making that movie and he compensated for the pain with a bottle of whiskey each day.

When I watched that demoralizing movie, I could smell the alcohol on his breath.

Sidewalks is pretty darned bad.

Worse than the average Hollywood movie?

No, not at all, but it’s exactly as bad as the average Hollywood movie.

Watching this movie is like suffering a nightmare from which you cannot awake.

It is watching the heroic Buster of 1926 reduced to being a lackey in the underworld.

Buster did not want to lose his job, though.

He had a choice: Either he could keep his salary or he could keep his sanity.

He chose to keep his salary.

He was basically okay with making this hideous junk that got him deathly depressed.

That was the price he had to pay to get his salary:

humiliation and ever-worsening deathly depression.

His true addiction was to a salary, a steady,

predictable stream of paycheck-induced highs, with bonuses to make the doses even stronger.

Alcohol was just the medicine he chose to compensate for his addiction.

In that respect, he was no worse than most people I have ever known.

We’re all addicted to salaries, and we all find some way of compensating.

Dardis (pp. 190, 200–201) claimed that Sidewalks of New York

was more profitable than any of Buster’s silent features.

Again, he cited only negative costs and rentals, as though nothing else matters,

and it is obvious from reading his text that he hadn’t a clue what he was writing about.

Nonetheless, countless people who should know better just took him at his word —

and continue to take him at his word.

(“Countless people” included me, of course. I’m ashamed.)

Well, I ain’t about to do a full study, but here’s what I recommend you do:

Go to the

October 1931 issues of Variety,

and, heck, go to the

November 1931 issues of Variety as well.

All the way through February, if you like.

Download the PDF’s, open the downloads, and do a search on the word “sidewalks.”

See what you see.

Oh yes, it opened rather well here and there, and overall it did quite nicely

in its

You can also check out the other trade publications, such as

Motion Picture Herald, but though they give more numbers, some of them quite impressive numbers,

there is less context, and so there is frightfully little to learn.

My conclusion, once again: If Dardis said it, chances are it’s wrong.

I hope this settles the issue, definitively.

It is a scandal that Penguin Books, which prides itself on publishing only the best, reprinted Dardis’s hopelessly inaccurate rot.

What happened? Did Penguin fire all its factcheckers?

|

Now, I have been a projectionist.

I worked as one off and on from 1975 through 2003,

and I can say, with full authority, that most movies are junk.

Terrible junk.

Unwatchable junk.

Pathetic, uninteresting, with stupid stories, unconvincing characters,

wretched dialogue, preposterous action, horrible acting,

worthless direction, incompetent editing, and terrible sound design.

The rare ones that are slick get passed off as good (Spielberg’s heart-tuggers, for instance).

They are not good. They are slick.

Yet not even a quarter of a century of being steeped in the worst that Hollywood has to offer

can prepare one for the unspeakable misery of the early MGM “comedies.”

Those demoralizing, nausea-inducing MGM products of the worst hacks who ever lived are in a class of their own.

They are the worst of the worst.

In charge of the ars gratia artis were Sadist Mayer as he colluded with gangsters;

Boy Wonder Thalberg as he charmed people’s pants off while stabbing everybody in the back,

and Bully Weingarten who saw intelligence only as childish stupidity.

For some unfathomable reason, those three monsters and others like them

were convinced that they knew how to make movies;

they were convinced that they knew infinitely more

than professionals who had spent their entire lives creating their own material.

Buster’s MGM features:

|

• The Cameraman (released 22 Sep 1928, production #366).

Beautiful.

• Free and Easy

(working title: On the Set;

20 Mar 1930, 453; also as Estrellados, 491;

there was also a German version, Buster rutscht ins Filmland, 2453,

and an Italian version,

Chi non cerca trova, 5453,

but Buster seems to have spoken only in the prologue).

Abominable.

No matter what mood you’re in, this movie will make it worse.

• Parlor, Bedroom and Bath

(20 Feb 1931, 539; also as Casanova wider Willen, Gr 539; and

Buster se Marie, Fr 3539).

An insult to the intelligence.

• Wir Schalten um auf Hollywood! (10 Jun 1931, 2462 and Gr462).

I have no opinion about the fragments that remain of this movie.

It included some leftovers from an abandoned movie called

The March of Time (1930, 462),

which had

included a sketch of Buster as a caveman.

Buster then

reappeared in his caveman

• Sidewalks of New York

(20 Sep 1931, 569).

A pathetic embarrassment, dreary beyond description.

Making it through, in one sitting, from the opening logo to The End, was an endurance test.

This is when Buster gave up and drowned his sorrows in endless jugs of whiskey, and it shows.

• The Passionate Plumber

(4 Feb 1932, 602; there was also a French edition,

Le plombier amoureux, Fr 3602).

I found this so irritating that I ejected the disc within five minutes,

unable to withstand the assault any further.

• Speak Easily

(4 Aug 1932, 627).

To my surprise, this wasn’t bad and it actually had a few promising moments.

• What – No Beer?

(working title: What Price Beer?

10 Feb 1933, 655).

A real stinkeroo.

Offensively stupid, utterly uninteresting, contrived beyond the point of forgiveness,

riddled top to bottom with humorless jokes.

Visually it was dismal enough to drive an audience to collective suicide.

Jimmy Durante’s part was so embarrassing

that I’m surprised this movie didn’t end his career forever.

I have no idea how he managed to live this one down.

MGM gave Buster the boot the moment this production was finished, and he was devastated.

Buster had never been fired before and would never be fired again.

He didn’t know how to handle it.

Getting fired, though, was actually the best thing for him at the time.

It forced him to rebuild a career and rebuild his life, almost from scratch.

The next 16 years or so were really bumpy, but he made it.

(Anecdote:

Everybody at work knew that I was wild about Buster,

but only one person at work had even a clue who Buster was.

The rest had never heard of him before.

Then, Monday, 11 September 1989, as I entered the building I found myself greeted by beaming faces.

My coworkers had finally seen Buster and they liked him!

The evening previous they had all watched What – No Beer? on TNT.

I wanted to shrink and disappear.)

|

Though six of these movies easily rank as among the worst ever made,

several of them had a most endearing element:

Anita Page.

She brightens Free and Easy and Sidewalks of New York.

She sparkles.

Even in the worst rôle, even with the worst dialogue, even in the dreariest scene,

even in the most abjectly awful subject, she sparkles.

So I looked her up on Wikipedia.

Her obituaries revealed why she retired from the movies at age 23:

“Page claimed that Irving Thalberg had offered her the starring role in three movies

if she would sleep with him, which she refused.”

Need I say more?

Orson Welles said more (My Lunches with Orson, NY: Metropolitan, 2013, p. 51):

|

Thalberg was the biggest single villain in the history of Hollywood.

Before him, a producer made the least contribution, by

necessity. The producer didn’t direct, he didn’t act, he didn’t write —

so, therefore, all he could do was either (A) mess it up, which he

didn’t do very often, or (B) tenderly caress it. Support it. Producers

would only go to the set to see that you were on budget, and that

you didn’t burn down the scenery. But Mayer made way for the

producer system. He created the fellow who decides, who makes

the directors’ decisions, which had never existed before.

|

Natalie, who seemed not to have had even the slightest sense of humor

and who seemed not to have enjoyed Buster’s movies,

had long before tired of Buster and had turned him out of their bedroom.

She was endlessly accusing him of having affairs with his actresses, which had never been true.

Have you met spouses who continually make such an accusation without any basis?

That behavior is extremely telling; it tells a great deal about the accuser, not so much about the accused.

(It was not until four years later that Buster finally did exactly what she had been accusing him of all along.

I don’t know, but I guess that, by that time, he was feeling down and hopeless and so why-the-heck-not?)

Buster explained that Natalie, upon the birth of the second child in February 1924, decided against having any further children,

and abstinence, apparently, was her preferred method of birth control.

That decision tells volumes about the hopeless state of the marriage.

It was Natalie’s mother and sisters who laid down the law:

By having given birth to two children, Natalie had fulfilled her wifely duties,

and, further, Buster had completed his task.

There was to be no further intimacy.

In response, Buster told Natalie’s mom Peg, in no uncertain terms,

that if he was no longer to function as a husband, he would get his kicks elsewhere.

Did he ever follow through on that promise?

I have my doubts.

I have my strong doubts.

Not until a few years later, anyway.

Things happened when MGM purchased him, as we shall see.

I do not know, but I suspect that what finally triggered Natalie was Buster’s constant routine of a few drinks too many.

Just a guess. I could be totally wrong about that.

I could go on to state my best guess as to why Buster was having a few drinks too many, but never mind.

Tracy Goessel,

who wrongly believes that Buster was indeed promiscuous at this time,

defends Natalie who sensibly did not wish to contract any diseases.

Well, yes, I hadn’t thought of that before.

Natalie was protecting herself from a nonexistent danger.

Even Joanna Rapf, in her Buster Keaton: A Bio-Bibliography,

accused Buster of “womanizing” (p. 19)

and further claims that he had had

“well-publicized affairs” with Viola Dana, Sybil Seeley, and Virginia Fox (p. 17).

Say what?

He and Viola dated for a couple of months and then continued to visit for a few more years,

but Joe Schenck convinced Buster to marry his sister-in-law instead.

Sybil and Virginia???? No way.

Well-publicized? Where?????

Let us turn to Rudi Blesh’s book, page 323, and ponder Buster’s remembrance,

which I am certain is accurate:

|

I was a star, and in Hollywood. It’s an automatic

problem in the best of circumstances. Why even Joe Schenck could

have second thoughts seeing a pic that he himself had chosen and

produced for Norma. No one could do a love scene better than she,

so convincingly that a man has to call himself aside: Is all of that

acting? Everyone said — and I believe — that Clark Gable’s love scenes

on the screen broke up his first marriage. Like all of us, he was on

the spot: look like you’re enjoying it and your wife jumps to conclusions;

look like you’re not and you’re out of a job.

It finally got so that Natalie practically took for granted that I had

an affair with every leading lady. There again, you’re stuck: keep trying

out new ones to get a good actress and you’re promiscuous, a

chaser; get a good one and put her on the payroll and it’s “Where are

you keeping her?” I was accused every picture. She knew I was chasing

them, and I knew I wasn’t.

|

To that, we can add a recollection from Gene Woodward Barnes, who recounted the filming of The General.

This is from Joanna Rapf’s book, Buster Keaton: A Bio-Bibliography (p. 24):

|

Everyone who worked with him loved him and was loyal to him, according to

Barnes.... Natalie was on location, and “cast a gloomy

shadow over Buster who was obviously unhappy around her.” She also

“cast a damper over the company, never mixing with them.” It was obvious

to everyone that they had problems, “but they were never discussed.”

|

Oh, I’ve met people similar to this.

I recognize all the

trademarks painfully well.

People like this were in my family, they were my teachers, school administrators,

church elders, coworkers, supervisors, bosses, and heck I even dated some.

Wherever I go, I see more and more, male and female editions,

of all citizenships, of all backgrounds, of all economic groups, of all political persuasions, of all levels of society.

My heart goes out to those who have to endure this treatment.

(Oddly, such antisocial characteristics are contagious, every bit as contagious as the flu.

When I was around them every day, almost every hour, I adopted them myself.

The day I got away, my repugnant behaviors ceased, completely, and oh my heavens what a relief that was!

I think that is quite typical.)

I am in a bit of agony because of a (rather famous) elderly friend whom I can no longer reach because of his own new predicament,

a wife who is isolating him from most family and friends.

Insomma, that is why I now have a cat.

Buster was painfully shy his entire life, especially around women.

Then, in 1928, four years after Natalie had kicked him out of the bedroom,

when he was on payroll as a contract actor for MGM,

he suddenly found countless starlets flinging themselves at him.

I suspect that “someone” (I’ll never know who) had paid those starlets to do that.

No. I lied. I don’t suspect it. I am absolutely certain of it.

See Bogdanovich’s The Great Buster, in which Jim Karen tells

that Buster would return to his MGM dressing room only to discover a naked woman inside waiting for him.

That was a running gag, apparently.

Yes, a studio head was pimping those starlets, for what reason, I can easily guess but I cannot know.

At first, Buster turned them all away.

Then he got an idea, a horrible idea.

With sudden access to a seemingly endless supply of pretty young things,

Buster made a point of demonstrating to Natalie that, if she did not want to live a proper married life,

he would make do with anyone else who would come along.

He spent nights with the starlets in his private bedroom, making a racket that Natalie could not help but hear.

To top it off, he began dating his current costar, Dorothy Sebastian, a fellow drunk.

Natalie was fuming.

Natalie had married an athletic, enthusiastic, vibrant, creative husband, bursting with energy and entirely faithful.

Buster and Natalie were a perfect mismatch, and less than three years into their marriage, Natalie called off all intimacy.

Then her brother-in-law canceled Buster’s job and gave him a different job that he despised.

Buster, driven by nature to be wildly creative, was suddenly forbidden from being creative,

and that was emotional torture.

Buster quickly became an ill-tempered and irresponsible drunk.

The marriage and the employment ended almost simultaneously.

Whose fault? Everybody’s.

Nobody understood anybody else.

Nobody had any training in how to deal with disagreements,

how to work through life’s basic little everyday problems.

Tragically typical, especially back then.

Ah. Look at this. This is an explanation I had run across decades ago,

but decades ago my mind was only half-formed and my experiences of humans were severely limited.

I read this again, and everything falls into place.

It is from George Wead and George Lellis,

The Film Career of Buster Keaton (Boston: G.K. Hall & Co., 1977), p. 5. Guarda:

|

Independent production brought Keaton fame and fortune. He had

joined Arbuckle for $40 a week, $210 a week less than he would have

made in the Broadway revue. He was up to $125 a week when he left

Arbuckle. By 1925, though, he was making $2000 a week, plus 25% of

his pictures’ profits — or approximately

|

Ah. Bus and Nat got hitched only in furtherance of the Talmadge/Schenck combine.

Heartwarming.

So, let us review.

Joe Schenck bought a small studio so that Buster could make movies.

Joe established a new corporation, which he named after Buster

but over which Buster would have no control and no shares or ownership of any kind.

Joe pressured Buster to marry his sister-in-law;

that way Buster would not dare to seek a different employer, as it would cause family rifts.

Buster did the work and so Joe earned a fortune.

Joe gave a portion of that money to Natalie, who gave Buster an allowance

and who treated Buster with nothing but contempt.

Joe then sold the studio without first telling Buster, and sold his contract as well.

Please, help me, somebody, I don’t understand why I am thinking this was an unhealthy arrangement.

What part of this was Buster’s fault?

His trust. His belief that everyone was trying to help.

Nobody was trying to help — not yet, anyway.

Joe, Natalie, the Talmadge clan, and the trustees were all taking advantage

of Buster’s earnings, his trust, his kindness,

and his natural inclination never to fight or to stand up for himself.

Jim Curtis’s new book (p. 447) reveals something I never knew about before.

Harold Lloyd, who was a very friendly fellow, did about the friendliest thing he ever did in his life.

He offered Buster a job in 1932.

Buster said Nothanx.

What do we know about this story?

Frightfully little.

It was Buster’s longtime friend Harold Goodwin who spoke with an Alan Hoffman of Costa Mesa, and told him,

“Clyde Bruckman directed a picture that I

did with Harold Lloyd, Movie Crazy. And Harold said to me, ‘I’d like to get

Buster to direct me.’ He wanted Buster to direct him, and Buster wouldn’t

do it. I don’t know why. I think Buster was so timid he didn’t like to order

people around. Of course, I’m prejudiced, but I think Buster knew more

about comedy than any of the others.”

The offer was apparently for a project that never got off the ground.

Why did Buster say No?

Was it because he knew from Clyde Bruckman that Harold’s working methods and his own were incompatible?

Or was it merely depression?

Whatever the case, Harold had sent a liferaft to Buster, and Buster said Nothanx.

That was a tragedy.

If only he had said Yes, he may well have gotten his career back on track

and re-established himself as a filmmaker rather than just a contract actor.

This is one of the most infuriating parts of Buster’s biography.

He had the opportunity to play hardball with MGM, but he chose instead to cave in.

He could have made an offer for Buster Keaton Productions,

or he could at least have attempted to purchase some shares to gain a say in the corporation, but he didn’t even try.

A kindly, caring colleague came along and offered him a way out of his mess, but he said No.

What can I say?

It was not MGM that destroyed Buster Keaton’s career.

The MGM execs were all a bunch of ogres with a collective IQ of 7 and they treated him horribly,

but he didn’t have to take their treatment, not for one second.

Yet he let those lunkheads walk all over him.

It was Buster Keaton who destroyed Buster Keaton’s career.

The unanswered question is Why?

Jim Curtis wrote something that threw me entirely off for a little while.

Jim suggests that Harold was readying The Cat’s Paw at this time,

and that this was likely the film Harold hoped Buster would direct.

But Harold had expressed his desire to hire Buster in about

February 1932, or maybe in March 1932 at the latest,

while he was shooting Movie Crazy.

The Cat’s Paw was based on a story by Clarence Budington Kelland that was published in the

Saturday Evening Post a year and a half later, on

26 August 1933.

So it was not The Cat’s Paw that Harold offered to Buster.

It was something else, a project that never got past the talking stage.

Was it depression, despair, defeatism that caused Buster to nothanx Harold?

Maybe. Probably. I think so. But I don’t know.

If, though, he was in a state of hopeless despair, that’s complicated a bit by what happened next.

When Buster got the boot from MGM, he was given the opportunity to direct an independent film in Florida

from his own story called The Fisherman.

He accepted enthusiastically, headed out in early June 1933,

and even got off the sauce for the two and a half months while he was there.

Unfortunately, The Fisherman never happened.

The financing was by an investor without experience, there were misrepresentations,

and the climate forbade shooting.

Buster packed up and returned to California in mid-August 1933, and that’s when he really hit the bottle.

Jim says that Buster was in no physical condition to accept Harold’s offer,

and he quotes a line from Buster’s autobiography, p. 245:

“I really started to hit the bottle hard after returning from Florida, and in a

short while I had a bad case of the d.t.s.”

Jim’s chronology doesn’t fit.

Buster turned down Harold’s offer in early 1932,

and he then gave up all hope in the middle of August 1933.

There was no connection between the two events.

The second does not explain the first.

This is all terribly puzzling, because we do not know what Harold proposed

and we do not know precisely how Buster responded.

And we’ll never know, because neither Harold nor Buster documented that conversation.

Most of Buster’s silent features had been rather small.

They had small casts, small costs, few locations, and lots of economizing.

The expenses were in the building of sets and large props.

The quality derived from the freedom to shoot scenes multiple different ways, off the cuff,

whenever he and his crew felt like it, without a script.

The General was done on a mammoth scale,

and it got the green light only because United Artists requested a movie on a mammoth scale.

Steamboat Bill, Jr., also had some massive effects that bordered on epic-scale .

Those days were numbered.

Upon the success of The Jazz Singer in October 1927,

the Hollywood studio heads made one of the dumbest of all their bone-headed decisions:

They unanimously agreed that they would phase out silent pictures beginning immediately,

and that, as soon as practicable, they would produce only talkies.

That, I am sure, was mostly a cost-saving measure.

The studios owned the cinema chains, and the cinema chains employed orchestras.

Well, now they could lay off multiple orchestras in every city in the US and Canada and save a ton of money.

That happened in 1929, exactly at the time that Wall Street Laid an Egg.

The result was thousands upon thousands of well-paid musicians suddenly being jobless and unemployable.

I have heard tell (though I have not verified this on my own) that this led to countless suicides.

The problem with sound films was that even in the best circumstances,

there could never be opportunities to improvise freely on an epic scale.

The technology did not and still does not allow for it.

The only way to have such freedom with a talkie is to make it entirely as a silent

and then later dub in some sound, but little or no dialogue.

Even with a dei Medici court to sponsor him with limitless funds and freedom,

Buster would never have been able to make a followup to The General.

The tools were taken away in 1928 and they have never been given back.

(Were I ever to become a billionaire, I would hire a full-time orchestra.)

Another problem, which has indeed been brought up before, is that he was aging, as so many of us do eventually.

How would he have adapted his style of humor to a more mature character?

Perhaps he would have found the magical solution that has eluded every other comic known to history.

We’ll never know.

Soon Buster suffered a nervous breakdown,

and that’s when he decided to dry out of his own volition.

Or, as Jim Curtis reveals, it was his agent’s idea, really.

Buster recalled that this was some variation on the

Keeley Cure,

a never-ending stream of drinks, with so much variety and so much quantity that the patients got physically ill.

Mixed in was a secret formula that seemed to contain ammonia and strychnine and ipecac among other ingredients.

Sounds to me like a prescription for death.

Buster then began a three-decade-long climb back to prominence.

Never again would he have the independence or the resources

to create anything close to the quality of his finest silent works,

but like the characters in his films, he made the best of the situation.

That demonstrates to me that the resilient characters he had created for the camera had contained a sizeable chunk of the real Buster.

His attitudes had shown through.

Under the guidance of his eminently sensible third wife,

dancer Eleanor Ruth Norris,

he learned to be at peace with the realization that his best work was behind him,

and so he concentrated on his other dreams —

purchasing a small ranch, getting back with his children, enjoying his grandchildren,

keeping close company with his friends, and performing as much as possible.

He accepted almost every offer to appear on stage, in musicals, in photo shoots,

in nightclubs, in circuses, on television, in magazine ads, in TV commercials, and in movies.