The Legal Challenge

|

|

This happens with probably every successful movie.

It is not plagiarism to be inspired by a book to create your own original work of fiction, provided your work truly is original,

which The General most definitely was.

It is not plagiarism to borrow from real life.

Plagiary suits are not, to my knowledge, filed against

|

|

That seems to be the end of the news stories.

I guess I can guess that the suit fizzled for lack of substance.

|

The Reception |

|

Few newspapers in those days published movie reviews.

What they published were stories from the press books, which many people thought (and many probably still think) were reviews.

They were not; they were publicity.

For actual reviews, one had to go to the fan mags.

In the winter 2001[/2002] issue of

The Buster Bulletin,

David Macleod went through reviews in popular movie magazines that the general public would likely have seen.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

“Brief Reviews of Current Pictures,”

Photoplay (May 1927):

|

|

Picture Play (May 1927):

Norbert Lusk gave it a negative review,

perhaps unique among contemporary fan magazines:

|

A Bizarre Claim |

|

Later on, in the chapter on

Бестер

Китон в СССР,

you will discover a review from a Ukrainian journal called Кино no. 12 (1929).

The reviewer, M. Romanivska, wrote:

“...we don’t understand the negative attitude of the American audience to Buster Keaton’s

new film, which has recently been released. ‘The fashion for sound movies’

is how newspapers explain the fiasco of Keaton and American audiences.”

|

|

Now, I have collected every available contemporary review.

Everything I have found you will find, too, on this website.

Most critics loved the movie.

A few didn’t, but that’s only to be expected.

One NYC critic, Martin Dickstein, mysteriously wrote that he was alone among NYC critics

in writing positive things about The General.

I have no idea what gave him that idea.

The other NYC reviews that I have found were mostly favorable, though I admit I’ve not found them all.

Perhaps we need to take account of an article in Variety vol. 89 no. 12, Wednesday,

4 January 1928, p. 8, in which the newspaper summarized United Artists’s claim as,

“Buster Keaton had a few [releases] but they got nowhere.”

Whoever it was at United Artists who said such a thing was not exactly telling the truth.

The General and College were both in release and were both doing quite well.

Steamboat Bill, Jr. “got nowhere”

for the simple reason that United Artists had declined to release it at all!

UA then refused to renew the contract to distribute Buster’s features.

It was not until after Buster was definitively out of their hair

that UA backed down and gave a half-hearted release to Steamboat Bill, Jr.,

beginning on 5 April 1928.

As for ‘The fashion for sound movies,’ that was a vicious myth created by the Hollywood movie studios.

People enjoyed seeing movies.

Sound or silent was not an issue.

So long as it was a movie and so long as it was reasonably entertaining, a passable diversion, it was fine.

|

|

From before the beginning until after the end, there has never been good communication between the US and the USSR.

My guess is that some unknown person on the outside fed Dickstein’s statement and the UA statement

to M. Romanivska, who, having literally nothing to gauge them against, took them at face value.

The unknown person may have also fed M. Romanivska some selected info about the success of

The Jazz Singer which led to the drawing of unfounded conclusions.

|

|

Yet the story gets even stranger.

Carlos Fernandez Cuenca penned a biography/filmography with the apposite title, Buster Keaton,

published by the Filmoteca Nacional de España, in Madrid, in 1967.

We turn to his entry on The General (El General) and on page 76 we read:

|

|

...La crítica

americana de la época, a juzgar por los fragmentos que trascriben Turconi

(págs. 51–52) no supo apreciar las excelencias de este película, la excepcional

maestra de la dirección, las muchas notaciones líricas que la adornan, la

ternura romántica que contiene; lejos de ello, cargaron la mano en la censura

sobre el tratamiento cómico de una página heroica; el crítico de Photoplay

llega a afirmar que Buster Keaton «satiriza despiadadamente» la Guerra Civil.

|

...The American

critics of the time, judging by the fragments transcribed by Turconi

(pp. 51–52), failed to appreciate the excellence of this film, the exceptional

masterful direction, the many lyrical notations that adorn it, the

romantic tenderness it contains; far from it, they charged the hand of censorship

on the comic treatment of a heroic page; the critic of Photoplay

goes so far as to affirm that Buster Keaton “mercilessly satirizes” the Civil War.

|

|

Ahhhhhhhh! Now we’re getting somewhere.

I’ve not yet read Davide Turconi and Francesco Savio’s

|

|

So, we have here a hasty error from 1929,

followed some decades later by a similar hasty error from 1963.

Both were committed by authors who seem not to have known even one word of English

and who certainly did not have access to the essential sources.

It is unfortunate that those two innocent errors have now become entrenched as Established Knowledge.

And since this is now Established Knowledge,

there is almost nobody who wishes to rock the boat by countering with good evidence.

Nobody wants to be so impolite.

Well, here I am.

|

Revisionism:

|

|

Buster Keaton said that The General was one of his three top financial successes.

And check out the lovely interview with

Marion Mack:

“...we were surprised when it took off as it did.

It was the audiences that made it such a hit;

the studio never realized what a gem they had in their hands until the money started rolling in.”

In English-speaking lands, this was commonly accepted knowledge,

and nobody thought to question or investigate what Buster and Marion had said.

Well, nobody — until Tom Dardis came along.

|

|

Tom Dardis’s mistake-ridden 1979 “biography,”

Keaton: The Man Who Wouldn’t Lie Down, shook movie scholarship to the ground.

He brought forth evidence that The General had been met with critical hostility

and that it had been a massive flop that would soon cost Buster his freedom.

He cited as evidence of The General’s poor reception

snippets from five reviews from New York City newspapers,

which were among the few newspapers that had movie critics on the payroll

(p. 144):

|

|

That, Dardis implied, was pretty much the sum total of critical and popular opinion.

Courtesy of online newspaper archives, I am now able to trace two of these five reviews,

and why am I not surprised to discover that Mordaunt Hall’s negative review is not quite so awful as Dardis makes out?

Why am I not surprised to discover that Martin Dickstein’s comments

are not exactly what Dardis attributed to him?

Why did Dardis not quote from reviews from elsewhere in the country?

As we witnessed above, most reviews outside NYC were quite flattering.

Heck, why didn’t he quote from other NYC newspapers?

He could have, and he should have, and you’ll see those other reviews below.

Basic rule: With but a single exception, if a review was favorable, Dardis ignored it.

If a review mentioned how much the audience enjoyed the movie, Dardis ignored it.

This is how history is done.

This is no different from the way history is taught in schools.

Sources are selectively quoted or even misquoted, while other sources that present different evidence are ignored.

The history we read in books is all balderdash.

|

|

Where did Dardis get that idea?

Did he actually believe what he wrote?

To the second question, the answer is “No,” at least not at first.

It is possible that he later came to believe his own deception.

To the first question, we also know the answer.

Actually, to the first question, we know both answers.

I shouldn’t say that.

We know all THREE answers.

Dardis’s sources were not M. Romanivska or Turconi/Savio or Fernandez Cuenca.

Chances are that Dardis had never heard of those sources.

Dardis used three different sources.

The joyous tedium of doing research reveals what the “authorities” had discovered before you got there;

you discover the sources that they accidentally-on-purpose neglected to footnote.

Here is what I just discovered on Monday, 21 November 2022.

We saw this above, but let’s look at it again:

|

|

The Film Daily was a trade publication out of NYC,

and it included snippets of the local NYC reviews.

This is what Dardis found.

He probably visited the library to grab the original reviews from the microfilms and maybe see if he could find one or two more, and he did.

He found

The Brooklyn Daily Eagle.

He quoted

The New York Daily Telegram

but wrongly ascribed the quote to

The Daily Telegraph.

He also quoted

The New York Herald-Tribune,

The New York Times, and

The New York Daily Mirror.

He skipped

The New York American,

the Daily News,

The New York Evening Graphic,

The New York Evening Journal,

The New York Evening World,

The New York Evening Post,

The New York Morning Telegraph,

The Sun, and

The World,

surely because most were less than entirely hostile and because some were even positive.

The Film Daily itself skipped

The Brooklyn Daily Times,

and so Dardis skipped that one as well.

Dardis pulled the snippets that served his purpose and he skipped the ones that didn’t.

Now I know Dardis’s first source, and now that I know his first source, you know it too!

Dardis wrote that NYC had eleven major papers that ran regular movie reviews.

The Film Daily quotes from thirteen NYC reviews.

So, which all were “major” and which all were not? I do not know. Do you?

|

|

A Plea for Help

Can you find the reviews of The General from the following (all circa Monday, 7 February 1927)?

The New York American

The New York Evening Graphic The New York Herald-Tribune The New York Evening Journal The New York Daily Mirror The New York World The New York Evening World The Sun The Evening Telegram The Morning Telegraph

If you find reviews in these or other publications, please send them along!

Many thanks!

|

|

Dardis’s second source was Louise Brooks.

Are you familiar with Louise Brooks?

If you’re not, you should be. I remember

Christmas Eve 1977, when Jim Card’s preliminary restoration of

Pandora’s Box

was broadcast on PBS, properly transferred at 20fps (75'/min), accompanied by

Bill

Perry’s seductively hypnotic piano score,

which, unfortunately, was never heard in public again.

(It was by leaps and bounds the finest score I have ever heard for that movie.

I’m lucky to have gotten a copy, transferred from the quad just before it gave up the ghost,

but my lucky copy, alas, is currently in storage; I must retrieve it.)

I was mesmerized by the movie.

The movie just knocked me away; it was easily one of the finest works of cinema ever made.

Louise Brooks was a name I knew but the name was all I knew, until that night.

She was magnificent.

She knew the secret of acting: Don’t!

She put little or nothing into her performance and just let her part tell itself.

Her underacting was easily one of the finest performing jobs I have seen, ever.

Beyond that, she was

|

|

Then, to my chagrin, I learned about her.

It was in

April 1990 that Diane Christian, Jim Card, Barry Paris, and Phil Carli presented a mini retrospective of Louis’s better movies

over the course of a Saturday and Sunday at the ugly Knox auditorium attached to the sumptuous Albright Art Gallery in Buffalo.

Barry told about his research into her life.

Jim told about his liaisons with Louise.

What I heard was too familiar to me.

I had experienced all these behaviors, exactly, which is why I was one step ahead of each story.

Louise definitely had some sort of personality disorder.

Jim told the story of visiting Germany with Louise.

While they were strolling down the street, Louise excused herself for a few minutes and Jim waited on the sidewalk for her.

Just then, he saw Fritz Kortner coming along.

Fritz had been Louise’s costar in Pandora’s Box.

Jim was overjoyed.

“Mr. Kortner! You won’t believe this, but I’m here with Louise Brooks,

and she’ll be back here in just a few moments.

Please wait around, because I’m sure she’d love to see you again.”

Fritz’s eyes grew wide in terror and he immediately ran away as fast as he could.

Yup.

That would have been precisely my reaction, too, concerning someone whose personality was a Xerox copy of Louise’s.

I understood. Perfectly.

All my illusions were shattered to pieces.

Louise was a depressive, self-destructive drunk, a manipulative nag with a temper.

Besides which she was just plain old nuts.

Intelligent? Absolutely! But nuts.

Oh well.

I’d rather know the truth than live in a fantasy.

|

|

I also learned not to take seriously anything she said.

She knew Buster a little bit, though how little I’m not too sure.

Probably very little. Very very little.

Maybe they were introduced at a gathering and said Hi and that was it,

except for maybe one or two later times when they bumped into each other and said Hi and nothing more.

Apparently Louise penned a fan letter to Buster,

regarding a shot of him hiding under the table

|

|

When Oliver Scott quoted that statement to Eleanor, to my surprise, she agreed!

See page 174.

On the other hand, the way Eleanor continues, she makes it clear that Buster was not forceful

and would not stand up for himself, and, further, that he was painfully shy.

Methinks that Eleanor understood something other than what Louise intended.

Louise was describing a suave womanizer.

Eleanor was describing a shy guy who might have responded if the gal were to make the first move.

|

|

Louise Brooks also told

anecdotes about Buster, but I have no reason to believe them.

(Barry Paris is convinced those anecdotes are true. Maybe he’s right.)

She had

a false story about his death, too.

So, in brief, she was not a reliable source, unfortunately, because she was a colorful, well-spoken, copious source.

It is so tempting to believe her, to hang on her every word. Oh well.

She lied.

We hear her stories and so we are convinced that we have the inside scoop.

We do not like to admit to ourselves that someone we admire lied through her teeth.

We do not like to admit to ourselves that we fell for it all.

I sure don’t like to admit it.

But she lied and I fell for it all.

|

|

Now, Aunt Louise wrote a letter to Kevin Brownlow, dated 23 November 1968,

and everybody takes this letter seriously.

Everybody except for me.

|

|

It was the title, The General. We thought Buster was playing a general, a

Southern general. Not funny. As an Englishman, you cannot understand that the Civil

War killed thousands of Americans fighting against their own families, almost

wrecking our country. Nobody connected The General with the name of an engine.

Many people stayed away. Those who saw The General were puzzled.

|

|

Oh dear dear Aunt Louise.

Love ya, Aunt Louise, but really now.

She was an eyewitness, in the know, who convincingly but wrongly claimed to have been in the inner circle,

an insider who seemed to know everybody and everything.

Everybody took her seriously,

but she had no idea what she was jabbering on about,

and the less she knew the more she jabbered.

Her jabbering, seemingly so innocuous, resulted in a cascade of problems,

as serious researchers attempted to square her stories with reality.

When evidence and Aunt Louise disagreed, it was Aunt Louise who invariably prevailed —

probably only because it’s so tempting to believe

such a marvelously eloquent raconteur who was an eyewitness and who was so darned entertaining.

|

|

Dardis fell for her tales hook, line, and sinker.

Either that or he pretended to.

One way or the other, he published her stories as though they were the definitive truth.

|

|

Dardis also got his idea from another source, a good, respectable, respected source:

George Wead.

George is a good guy and a good researcher.

I met him, though I am sure he wouldn’t remember me.

He wrote “The Great Locomotive Chase” for

American Film: Journal of the Film and Television Arts, vol. 2 no. 9, July/August 1977, pp. 18–24.

For the most part, it’s an exceptionally good article, with info that had never been published before.

Yet he opened his good article with an uncharacteristically bad summary:

“The nation’s major film reviewers wrote off The General as an extravagant mistake....

Others dismissed the film more quietly.”

Now, where, pray tell, did George get that idea?

Why did he choose quotations so selectively?

Did he, perchance, see that summary in The Film Daily?

No. I’m sure he didn’t, at least not at first.

What I bet happened is that George, aware that some guy named Dardis was working on a new biography,

wrote to the author to ask for some representative reviews.

And guess what Dardis sent him.

Therein lies one of the common pitfalls of scholarship.

It is a pit into which we have all fallen too many times.

If my intuition is correct, and I bet it is:

Dardis faked it,

George copied Dardis,

and then Dardis copied George’s copy of Dardis.

Each pointed to the other as confirmation.

Just like college professors, yes?

|

|

Dardis latched on to the idea of critical objection to The General and then he piled on,

and when he piled on, he chose his facts most selectively.

What little evidence seemed to support Louise, George, and Film Daily, he quoted gleefully.

The mountains of evidence that contradicted Louise, George, and Film Daily,

well, he didn’t find that of any interest and so he left it all out.

|

|

Small beer, isn’t it?

A nonacademic scribbler publishes a popular book without peer review

and lies about what movie critics wrote half a century before.

Big deal, right?

We have many more important things to worry about, yes?

Well, there really is a problem here, and a huge one.

That tiny little irrelevant lie had an effect that reverberated across the whole book,

and it distorted the entire “biography.”

The

|

|

Since the publication of Dardis’s book in 1979,

countless cinema historians, Buster biographers, critics, and commentators

have repeated the brief quotations that he supplied in that short passage reproduced above.

Do web searches on those five direct quotes and you will find them all over the place, verbatim, with ellipses in the same places.

To the best of my knowledge, no researcher has tried to replicate his research.

Whenever I attempt to duplicate a scholar’s research, I get radically different results.

That is certainly the case here.

Be patient and read through what I discovered.

At first, you will find that my objections are strained nuances, pointless nitpicks.

Keep on reading.

Pretty soon, you will find that much of the evidence is the reverse of what Dardis claimed.

I invite you to continue this project.

Visit your libraries, find the reviews in your home town,

and, if the information by some miracle is still available,

dig up the data on the ticket sales and

|

|

Here is

Mordaunt Hall’s full review, not much different from what Dardis implied, but slightly different,

and that slight difference makes a difference:

|

|

|

For the life of me, I have not the foggiest notion what “a mixture of cast iron and jelly” means.

It is clear that Mordaunt Hall misunderstood the movie, and that is hardly surprising.

It’s not his cup of tea, and that’s fine, but he did mention that the audience were laughing.

Dardis wrote that Hall’s review was negative, and, yes, he was right, it’s pretty negative.

The point I wish to make is that Dardis characterized Hall’s review as “completely hostile.”

As you can see, it is not.

It is not a favorable review, but it is by no means “completely hostile.”

Am I nitpicking?

Yeah, maybe.

|

|

By the way, only just now do I notice the point that Mordaunt Hall was making.

His objection was that Buster was not so much a clown in this movie.

Correct.

Buster played it straight, entirely straight.

Mordaunt preferred to see clowning.

Buster had clowned around in his short films, but not so much in his features, and there was a reason.

A short film can be jokey, cartoony, silly, implausible, improbable, impossible.

Once a movie is much more than about 15 or 20 minutes, though, such jokiness gets to be tiresome.

A longer story needs to be plausible; it needs to have a structure that would stand on its own even minus the comic elements.

There are exceptions.

The Cocoanuts, or what little is left of that butchered movie, got away with feature-length silliness and clowning — well, mostly.

The same holds true for

Monty Python and the Holy Grail — well, mostly.

Zazie dans le métro also got away with it — well, mostly.

Those are the rare exceptions that prove that horsing around can be done nonstop for a good 90 minutes without wearying the audience too much.

Those are rare exceptions.

There may be a couple of others.

Some people might say that

Airplane! was another example.

Buster couldn’t think of a way to clown around for an hour or more and get away with it.

Charlie Chaplin couldn’t think of a way to do that either.

Neither could Harold Lloyd.

Not even Laurel & Hardy could work it out.

Once they made movies that ran much more than 20 minutes, they all cut down on the clowning, a lot, and they beefed up the stories, too, a lot.

The characters and the situations had to be credible, or somewhat credible, else there would be nothing to hold the story together.

As a rule, clowning is good only in small doses, very small doses.

As you read some of the other negative reviews, you will find that

a minority of critics made it clear that they wanted to see silly horseplay, pie throwing,

clumsy nincompoops falling into mud puddles and slipping on banana peels,

and not straight comedy in a plausible story.

Let’s get back to my nitpicking.

|

|

Here is Martin Dickstein’s actual review.

Dardis claimed that this review recognized The General “as a work of genius.”

A work of genius?

Dickstein implied no such thing.

He wrote that it was an exceptionally fine film, not “a work of genius,” please.

I hate such exaggerations.

It’s instructive to read the review in its totality:

|

|

Here is Martin Dickstein’s defense of his review, which, as you will notice,

was rather distorted by Dardis:

|

|

Note that Dardis attributed to Dickstein the judgment that

“Probably lots of people... will not think it funny at all.”

Yet that is not what Dickstein wrote.

That phrase is not Dickstein’s; it is a quotation from the New York Evening Post,

and when we fill in the three dots, we discover that the actual statement was,

“...probably lots of people, used to the something-funny-every-second school of comedy, will not think it funny at all.”

When we restore the middle of that sentence, the meaning is startlingly different, isn’t it?

So why do you suppose Dardis omitted it?

It is true that someone expecting to see wild slapstick and zany madcap humor with boisterous laughter throughout

would be disappointed by a straight comedy.

Now I understand.

I am often confused by other people’s opinions — until they are eventually explained to me.

|

|

Please take note of Dickstein’s careful wording:

“...one or two constant readers were prompted, even, to write in to take exception.”

Well, was it one constant reader or two?

Dickstein knew the exact count, but he refrained from citing the exact number.

Why?

The answer is simple.

Had he told the truth that “one reader was prompted, even, to write in to take exception,”

that one reader, though not identified, would likely have felt outed.

So, Dickstein, to soften the story, made it a bit vague, added an adjective, and turned “one reader”

into “one or two constant readers,”

and that is how we can discern the precise number of letters of complaint Mr. Dickstein received from all his readers,

not just constant readers — the grand total was ONE.

Oh how much I would love to read that one letter.

I suppose it landed at the bottom of the city dump nearly a century ago,

but if, perchance, you have Martin Dickstein’s files and that letter is still there,

please let me know. Thanks!

|

|

Since Dickstein quoted from the

New York Evening Post, Monday, 7 February 1927, p. 12,

which I only now discover is freely available online, shall we take a look at it?

It is by

Wilella Waldorf (isn’t that a great name?), and it is about as nice and warm as a review can possibly be:

|

|

Martin Dickstein, as we saw above, wrote that his review and Wilella Waldorf’s were the only two in “this town”

(NYC’s five boroughs, not just Brooklyn) to write favorably of The General.

He was wrong.

Several other NYC reviewers wrote favorably of it as well, as we shall see.

|

|

The Brooklyn Daily Eagle, which Dardis quoted, circulated pretty much only in and around Brooklyn.

Its influence was thus minimal.

The New York Daily News, on the other hand, was major, with circulation around the country.

So, why did Dardis neglect to cite the review from the New York Daily News?

|

|

Here’s a mixed-leaning-to-positive review that Dardis chose not to mention, from The Brooklyn Daily Times:

|

|

The opinions of critics seldom interest me, but something else does interest me:

The critics’ reports of audience reactions.

Martin Dickstein in The Brooklyn Daily Eagle mentioned the “hysterical outbursts.”

John Cahill “Jack” Oestreicher of The Brooklyn Daily Times,

though he disliked the film, saw fit to mention “a crowded house”

that “roared a tumultuous reception,”

displaying “prolonged and unrestrained laughter.”

“The audience laughed with right good merriment through it all,” wrote Oestreicher,

continuing, “we suppose the function of a comedy is to make people laugh,

and there, unquestionably, ‘The General’ fulfilled its destiny.”

So, even though 21-year-old Oestreicher personally disliked the movie, I feel justified in classifying his overall review as positive.

Please keep these audience reactions in mind when you read the

|

|

Dardis mentioned Robert E. Sherwood’s negative review in Life, and left it at that.

Yes, it was a negative review — mostly.

Sherwood found the film ingenious.

He liked it, much preferring it to the vast majority of films,

but the killings on the battlefield upset him terribly.

A single sequence, with cannoneers and a sniper,

lasting one minute and three seconds, ruined the whole experience for him.

Take a look:

|

|

According to Dardis, the ledger books revealed that the film was a flop, with a domestic gross of only $474,264.

In an endnote, Dardis claimed he got that figure from the Wisconsin Center for Film and Theater Research.

If that figure is correct, then it was domestic rentals, not domestic gross, and there is a world of difference between the two.

Let me explain.

Suppose you want to book the latest Dummy movie, which promises to be a hit.

Your booker tells you that the terms are that you pay $10,000 up front as a minimum guarantee.

That’s the “rental.”

Your booker already knows your “nut,” the cost of operating your business

(salaries, mortgage, insurance, utilities, maintenance, and so forth),

and has reported your “nut” to the distributor.

You deduct the “nut” from total

|

|

To put this more plainly, RENTAL is down payment,

GROSS is total ticket sales,

NET is how much the original investors earn back from rentals and grosses.

|

|

My psychic powers and the invisible nixies dancing above my head

and the cosmic vibrations and the Celtic faeries and whatever else you happen to believe in

are all telling me that you entirely disbelieve me,

simply because what I scribble here contradicts what Dardis wrote.

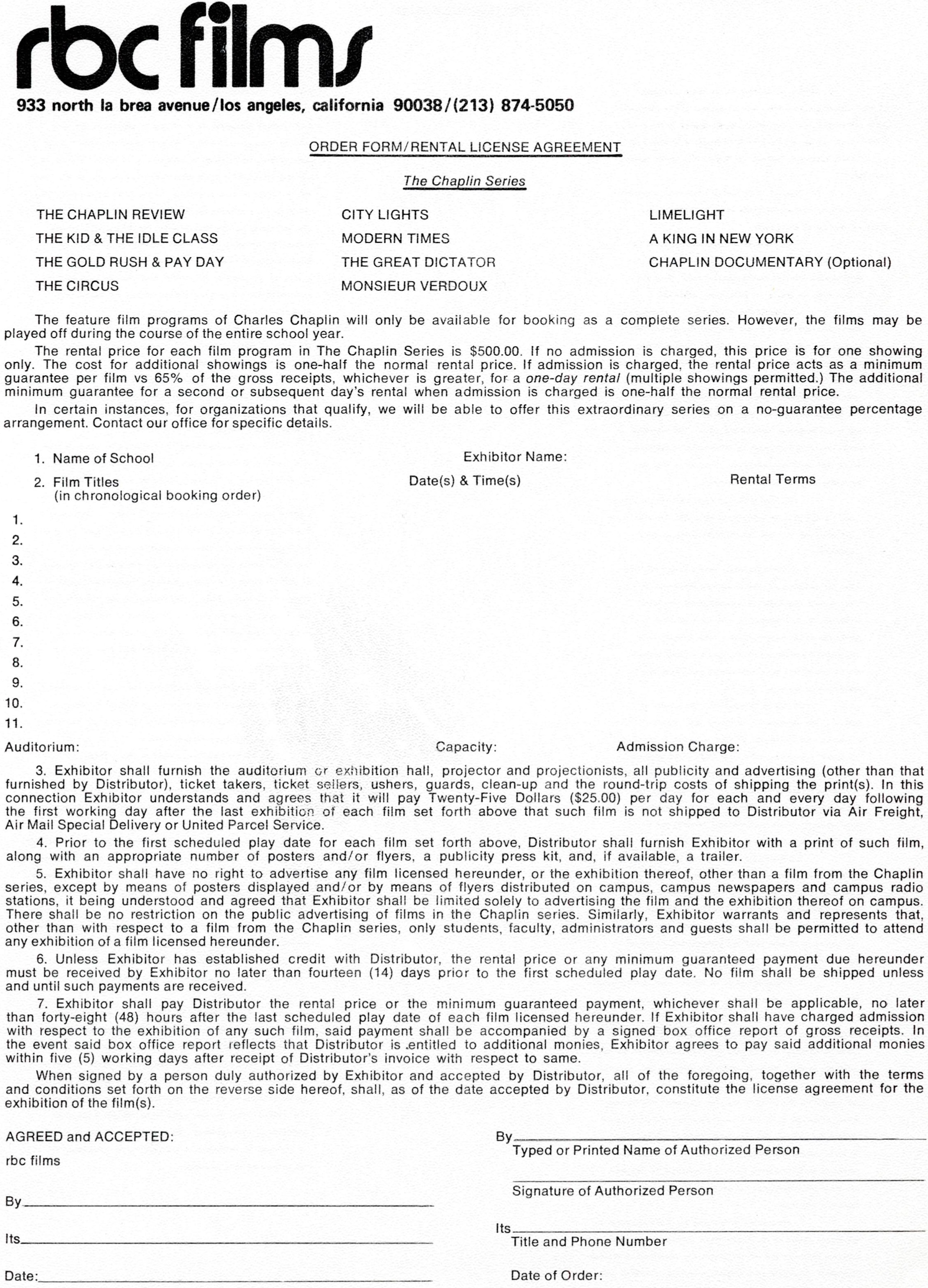

Okay. Here’s an example of a rental license:

|

|

|

Note that the $500 rental fee is the MINIMUM GUARANTEE.

The contract stipulates that the amount due is 65% of the GROSS ticket sales versus the rental, whichever is greater.

As is usually the case, all the risk — ALL the risk — is borne by the exhibitor.

Importantly, note that certain qualifying institutions may book this series on percentage only, without a minimum guarantee.

Those, of course, would be the institutions with a good track record of routinely high attendance.

More importantly, note that there is no option for

|

|

To claim that a film earns only its rental fees

is like claiming that a bank earns only the down payment and not the mortgage interest.

Yet I see this argument made over and over and over and over again in the literature.

If film professionals ever bother to thumb through these books, they probably get a good laugh from them.

|

|

No one has ever researched the earnings of The General, and it may simply be that the records no longer exist.

Until someone (me?) does some research, I think we should perform a thought experiment:

If The General were such a massive financial failure, then why was it kept in circulation for more than two years,

often with large display advertisements in the newspapers?

If the movie were a bankrupting dud, the money people would have cut their losses and yanked the film from distribution.

If I can ever get back to the libraries, I’ll scour the vertical files and I’ll jot down what few figures are available.

I’ll see what I can derive from that information.

My guess is that I’ll discover that, domestically, The General did no better and no worse than the typical Keaton feature.

|

|

I have never had money enough to invest, but I do know something about investors.

One of the first rules of investing is that returns must be FAST and that they must be 700% minimum.

Buster’s investors, had they plopped $225,000 into a production,

would not be happy with total worldwide grosses of <$500,000.

No way. They’d go broke at that rate.

After cinemas took off their costs and percentages, and after distributors took off their costs and percentages,

$500,000 would leave only a deficit for the original investors.

Clearly there is something wrong with this picture.

|

|

Also, let me bring forth a comment by David Kalat on the commentary track of the Eureka “Masters of Cinema”

|

|

In a footnote, Dardis explained that he had gotten his counts from the MGM files.

Now, it turns out he used worldwide grosses for some of the films and only domestic figures for the others.

And in any case, MGM merely distributed the first batch of films,

which went up through this one, Sherlock Jr., as a distributor for hire;

and then beginning with The Navigator they were operating under a new agreement with MGM

that changed how the earnings would be tabulated.

Dardis simply hadn’t compared apples to apples, and Buster’s numbers had been right all along.

|

|

Yes, the first three Schenck/Keaton feature productions were licensed to Metro for distribution,

and the understanding (unfulfilled) was that they would be five reels each.

See my essay on “The Mystery of Buster’s First Three Features.”

In the succeeding four films, The Navigator through Battling Butler,

Metro was apparently a shareholder rather than mere distributor,

or, at least, that’s my educated guess, based on nearly nothing.

How I wish I could find the contracts.

|

|

For whatever it’s worth,

Exhibitors Herald vol. 32 no. 2, 24 December 1927, p. 38, reported that four (only four)

cinemas claimed that The General was their biggest money maker for the fiscal year ending 15 November 1927,

and Buster’s previous movie, Battling Butler, had the identical result.

Those results were good enough to put those two movies onto the second-tier list of successes.

That doesn’t seem to be bad, and it’s actually pretty good, but it is not by any means magnificent.

No Buster movie was good enough that year to make

the top-tier list of the year’s sensations.

Among the flicks that beat out The General were

Rookies,

Tell It to the Marines,

Slide Kelly Slide,

It,

Beau Geste,

3 Bad Men,

Laddie,

The Black Pirate,

McFadden’s Flats,

Tillie the Toiler,

Twinkletoes,

Getting Gertie’s Garter,

and on and on and on.

Some really good flicks are included, but, for the most part,

I guess we can conclude that tastes change.

|

|

Let’s scout out a bit more.

For the fiscal year ending 15 November 1925, The Navigator made

the top-tier list,

with 19 cinemas reporting it as the year’s highest performer.

On

the second-tier list, Go West, Our Hospitality, Seven Chances, and Sherlock Jr. made their appearances.

|

|

For

FY ending 15 November 1928, no Buster movies made the top tier, but in the second tier we find

The Cameraman with 3 cinemas reporting it as the top attraction,

College named by 6 cinemas,

and Steamboat Bill, Jr., named by 1 cinema.

|

|

There are no numbers associated with any of the above.

I do not know what the profits were or who made them,

but these little lists do indicate that, between late 1923 and late 1928, no Buster movie was a failure,

and one of them, The Navigator, seemed to be an exceptional success.

Buster’s movies presented solid, secure investments,

but nobody would be able to retire off of them.

|

|

To get precise figures —

negative costs, production costs, sales, rentals, grosses, percentages, returns, profits —

will require some more work, and, like I said above, there is a good chance that these data no longer exist.

|

|

As far as I am concerned, Dardis wrote nonsense.

He focused on only the smallest sampling of reviews, quoted from them misleadingly,

discarded evidence that told a different story,

pulled only a few figures from the ledger sheets, misrepresented them,

drew a completely incorrect conclusion,

and extrapolated that incorrect conclusion to color numerous other stories.

Why did he do that?

I can think of two possible motivations.

Perhaps he was just so clueless about the movie business that he didn’t even know the difference between a rental and gross ticket sales.

Or, perhaps, he was trying to make a name for himself.

If he could demonstrate that all previous writers were wrong, then he could sit back and let others wonder at him in awe.

If the latter was the case, then it was a terrible gamble, because it would have taken only a single researcher to call him out.

Perhaps he wanted to take that risk, confident that probably nobody would know enough to call him out.

Well, now, 43 years later, I’m calling him out.

Too late to challenge him directly, though,

since he died in 2001, less than three months after the screening of The General at the Buffalo Film Seminars.

|

|

As an old colleague used to say, this is an example of “polluting the information stream.”

Though anyone familiar with Buster’s life and career would instantly recognize

that much of what Dardis wrote was obviously careless and poorly reasoned,

his book nonetheless had a powerful impact.

I confess: For years, I was entirely taken in by Dardis’s claim about the financial failure of The General.

Years? Nay, decades!

Even at age 19 I knew better than to fall for such claptrap, but I fell for it anyway.

Two numbers, just two numbers, unconfirmed, are not enough to settle a case,

especially since it seemed obvious, even to stupid-19-year-old me,

that the alleged domestic gross could not possibly have been anything of the kind.

Why was I that dumb?

I’m trying to think about it.

I think these were my reasons:

“Dardis is a published author and he examined studio documentation that is unavailable to me and, further, he has endnotes.”

He thus became an authority.

Then I saw that so many other credible, trustworthy sources agreed with Dardis’s research and conclusions.

Who was I to naysay them all?

Especially since nobody, absolutely nobody, expressed the smallest doubt about Dardis’s conclusion.

Sheesh.

Biographers, historians, and enthusiasts were all taken in.

We all reinforced each other’s incorrect conclusions.

Even some of the finest scholars,

conscientious and exacting researchers who were not likely to be deceived, were nonetheless deceived.

We were all taken in.

And we were all wrong.

Dardis’s hogwash instantly became unquestioned dogma — and remained such for four decades.

In no time flat, it went viral; it became a credo, a cult belief.

Even today, his flummery remains in vogue and is considered accepted knowledge.

Jim Curtis and

a few others

have only recently begun to contest Dardis, but only mildly, hesitantly, and without conducting solid research.

I’m not as courteous as the others, partly because I resent what Dardis did,

partly because I am angry with myself for having been hornswoggled by him,

but mostly because people I admire are still bamboozled by the guy.

It’s time to do proper research, on our own, and to state, loudly,

that if Dardis wrote it, we should disbelieve it until and unless proof is forthcoming.

My educated guess: Everything Dardis wrote, every fractional piece of purported evidence he presented,

every argument he made, and every conclusion he drew was slanted — or worse.

|

|

Dardis’s book was published on 16 February 1979,

and that’s right about when I first learned of it, when I saw it on display at the UNM bookstore.

I had zero money with me at the moment, but somehow I scraped together the needed $12.50 over the next week or two

and purchased it and devoured it.

The book was designed to leave a bad taste in our mouths in regards to Buster.

It left a bad taste in my mouth, for sure, but regarding Dardis.

I just didn’t trust him.

Yet I fell for some of his claims.

|

|

Dardis’s book is junk. It is trash. NOTHING in it can be trusted.

It is to biography what Erich von Däniken’s Chariots of the Gods? is to science.

It is to biography what “Infowars” is to news.

Junk. Trash. Asinine idiocy.

Lie after lie after misrepresentation after misrepresentation.

It should never be used as a source of information, because it contains only misinformation.

|

|

There’s a book even worse than Dardis’s, you know.

I read it the moment it was published (October 1995), and I read it all the way through on the day I got it,

and it was difficult to locate any honest, accurate, unbiased statements, anywhere, first page to last.

There were a few.

For instance, there were such statements as, “Keaton remained at the VA hospital three weeks.”

For the most part, though, everything had a slant, a spin, an insinuation, a strategic omission, an embellishment,

on top of which the research was deplorably inadequate.

Much of what it passed off as verified fact was instead guesswork that was completely wrong.

Shall we take a look at a representative sample?

|

|

...The world premiere was scheduled for the end of December

[no citation, but the world première was 11 Dec 1926 in Columbus]

in New York

[no citation, but the NYC première was scheduled for 1 Jan 1927], followed by special showings in Tokyo

[no citation, but the opening in Tokyo, Kobe, Kyoto, and Nagoya was 31 Dec 1926,

and those were not special showings, just a regular release]

and London

[no citation; the London opening was 17 Jan 1927;

I am unaware of any special showings prior to January 1953]....

The General had its first screening on New Year’s Eve at two movie theaters in Tokyo

[no citation, but it had opened three weeks earlier in the US;

it opened on New Year’s Eve at FIVE major cinemas in FOUR cities in Japan].

Its American premiere at the Capitol was now set for January 22, 1927

[wrong;

that was to have been its NYC première, not its American première].

To publicize the film, the engine bell from the real General was shipped to New York and displayed in the theater lobby.

But for the first time in its history, the Capitol held over a film

for a third, then a fourth week, creating a booking problem. It was

the winter’s most talked-about movie, Flesh and the Devil, starring

Greta Garbo and John Gilbert. At the end of January, Joe Keaton

accompanied his son to New York

[this is a misreading of

The Brooklyn Daily Times, Wall Street Edition, 20 Jan 1927, p. 6A;

Buster and Joe did not travel to NYC; no personal appearance was scheduled],

only to find the premiere postponed.

They headed back to the Coast

[Joe and Buster did not travel to NYC, and so they did not return from NYC;

that was just useless guesswork to make sense of the wrong assumption],

because Keaton had to start a new picture. The General finally did open on February 5, on

a program that included a short called Soaring Wings, a study of

vulturous birds.

New York reviews ranged from lukewarm to savage

[I have so far found 4 positive reviews and 1 negative,

but, admittedly, I’ve not yet found them all].

To the

Herald-Tribune, the picture seemed “long and tedious — the least

funny thing Buster Keaton has ever done”

[no citation, but obviously from Dardis].

Variety labeled The General

“a flop,” placing the entire blame on Keaton: “It was his

story, he directed, and he acted.” The Telegram saw it as a rehash

of old Mack Sennett shorts

[no citation, but obviously from Dardis],

while the Mirror critic flogged Keaton

for being self-indulgent and no longer capable of producing a feature-length film

[no citation, but obviously from Dardis, and exaggerated].

Between the lines the press suggested that this

was a costly boondoggle, made to satisfy an egomaniac

[balderdash].

The General seemed to be the Heaven’s Gate of the twenties. Even

Keaton’s admirer Robert Sherwood said that “someone should

have told Buster that it is difficult to derive laughter from the sight

of men being killed in battle”

[amazingly, this is cited, and, as we saw above,

it is a tendentious reading of Sherwood’s review].

Not all the New York critics disliked The General. One

described it as a moving daguerreotype

[no citation, but this is from the NY Evening Post, which we saw above].

The Brooklyn Eagle gave

the film a favorable review, but afterward the paper received letters

of protest from moviegoers who had felt like walking out, and

some who perhaps had.

[Really? Read the source document above: “one or two constant readers

were prompted, even, to write in to take exception.” That’s all it said.]

The Capitol gave the picture its standard

one-week run. It was succeeded by The Red Mill starring Marion

Davies, Roscoe Arbuckle’s first directing feature. According to the

Exhibitors Daily Review, the Capitol took in $50,992.80, an average

intake and only some $15,000 less than the Garbo-Gilbert sizzler.

It was not really a problem of moviegoers failing to show up.

They did. But they left disappointed.

[For the record, the four weekly gross ticket sales for Flesh and the Devil

were $71,446, $61,059, $59,760, $56,031, all far above average for the Capitol.

Ticket sales for The General, $50,992, were at the high end of normal.].

A number of theories have been put forward to explain the

film’s failure

[no citation]:

the delay in opening, ineffective distribution by

United Artists, and unfair notices from vicious reviewers. Louise

Brooks, a friend [passing acquaintance at most]

of Keaton and an admirer of the film, believed

that the trouble lay in the title:

Moviegoers stayed away because

nobody connected The General with the name of an engine.

They thought the movie was about a Confederate general,

or perhaps a comedy about the war

[no citation, but this is from Louise’s letter to Brownlow, which we saw above].

Insufficient time might have passed for

Americans to make jokes about a national tragedy

[no citation, and what about

Hands Up? what about Grandma’s Boy? and those were not the only ones!].

Indeed, to people whose parents or grandparents had fought in the Civil War, it

was still a highly charged subject.

The main reason for the failure of The General seems to be less

complicated. People who paid their admissions to a Buster Keaton

comedy expected it to be uproariously funny. But where were the

big laughs? Where were the pratfalls? At this point in his career, it

was impossible for Keaton to step out of genre and take his audience with him

[what about

Battling Butler?].

Even though people could see The General’s extraordinary

beauty and appreciate its dramatic power, they were

unable to move past his reputation as a slapstick comic and accept

him in the role of a fine director

[no citation].

In the end, The General cost over $750,000

[no citation, and that figure is inflated by about $250,000],

which was

$365,000 more than the Navigator

[no citation]

and $383,000 more than Go West

[no citation].

Its domestic gross of $474,264

[no citation, but obviously from Dardis]

was $300,000 less than

Battling Butler and $400,000 short of being classified as a profitable film

[no citation].

The picture would not show a profit until it was “rediscovered”

some three decades later

[no citation].

In the seven decades since the film’s release, Keaton’s epic has

come to be regarded as one of the monumental works of the silent

film era. It is primarily this film that would lead serious cinephiles

of the fifties and sixties to turn Keaton into the darling of Cahiers

du Cinema and Sight and Sound.

Never did Keaton understand why The General scored so poorly

[for the obvious reason that it didn’t].

“I was more proud of that picture than any I ever made,” he said in

1963. “Because I took an actual happening out of the... history

books, and I told the story in detail, too.... I laid out my own continuity,

I cut the picture, directed it. And I had a successful picture.”

After the beating he took on The General, he retreated to safer

ground

[there was a different reason].

Next Keaton chose to do a picture

[he didn’t choose, Schenck and Brand chose for him]

that required as little intellectually from him as possible. In the rainy winter of 1927

Keaton

began filming College, his eighth feature and one of the his weakest,

though it is unusually rich in gags....

|

|

I’ve repeatedly seen this same sort of thing happen in academia:

Inventing hypotheses to explain a phenomenon that turns out not to exist.

For example, I remember, with pain, a statistician explaining, at great length, an unexpected result in an analysis of population data

by postulating, without any evidence, all manner of potential ambiguities in the official collection of that data.

Yet the phenomenon had already been totally debunked as a file-drawer effect.

Once we factored back in the suppressed data, the anomaly vanished.

I listened to this statistician in dumbfounded disbelief,

because I knew full well that he had examined the recently discovered unpublished data

and I knew full well that he knew better than to spout such nonsense.

Nonetheless, he felt compelled to make his mark, and so he babbled this rubbish.

I wanted to say something to the statistician afterwards, but my boss would not allow it.

|

|

The biographer made mention of “the rainy winter of 1927” and so I looked it up.

It was 2.78" above average, which I didn’t think was any big deal.

Then I ran across an editorial that changed my mind.

There was a rainy month, though I suspect that the editorial took some artistic license with reality:

|

|

In response to one particular statement in the biography’s passage,

“At the end of January, Joe Keaton accompanied his son to New York, only to find the premiere postponed. They headed back to the Coast,”

I referred you to the

Home Edition

and to the

Wall Street Edition of The Brooklyn Daily Times, Thursday, 20 January 1927, p. 6A,

but if you try to search for that on your own, you’d probably never be able find it, as it’s buried amidst numerous other editions

of that day’s paper,

and the online archive does not file it under The Brooklyn Daily Times, but under the Times Union.

Guaranteed confusion.

We saw this above. Let’s look at it again to see what it really said.

The biographer quoted above assumed that this little article meant that Buster and Joe would appear together on stage

in conjunction with the movie.

That is not what it says at all.

It says that Buster and Joe are reunited on screen:

|

|

As was typical with larger cinemas back then, the feature presentation was the centerpiece of a larger show.

At Loew’s Capitol that week, the rest of the show consisted of

Soaring Wings, an

Ufa documentary short about wild birds

(I can’t find any ready references to this movie’s current availability,

and so, I suppose, this film may have vanished off the face of the earth).

There was also a

Chester Hale ballet called Milady’s Boudoir;

Lucius Hosmer’s Northern Rhapsody, played by the Capitol Grand Orchestra under the baton of

David Mendoza;

together with a new Irving Berlin ballad, “What Does It Matter?” sung by

Celia Turrill and

Westell Gordon.

There was also a custom-assembled reel, part of a series called “The Capitol Magazine,” featuring clips from current newsreels.

So, how was this summarized above?

“The General finally did open on February 5,

on a program that included a short called Soaring Wings, a study of vulturous birds.”

Do you see the trick that was played on the reader?

I thought I saw the trick, but the trick was trickier than I thought.

Behold:

|

|

The author of the book, perfectly well aware of the full extent of the program,

decided to ignore the other sources that detailed the prologues

and instead to rely on the press release as published above.

It is obvious that the

|

|

We saw above how this biographer offered several hypotheses to explain audience hostility towards The General on its original release.

Some of those hypotheses are downright bizarre.

One hypothesis is that “the delay in opening” may have been responsible.

What?

Okay, let’s turn this into an imaginary dialogue between a wife and a husband, both of whom are casual movie-goers.

Wife: “Let’s go see the new Keaton picture.”

Husband: “Are you crazy? We don’t want to see that.

The weekly trade journals said that it was scheduled to open a month ago but was delayed.

We don’t see pictures that have been delayed. It’s just not done. Ever. Got it?”

Please.

“Unfair notices from vicious reviewers”?

Every movie gets unfair notices, every movie gets negative notices, every movie gets vicious notices,

every good movie gets unfair notices from vicious reviewers.

Notices can affect business, but their influence is limited.

Besides, the majority of the reviews of The General were positive.

All of the above hypotheses are worthless.

Not one of them is based upon reality or any evidence.

Purest fantasy, and poor fantasy at that.

Why does the hostile audience reaction need explaining, anyway?

No explanation is needed.

You see, I’m letting you in on a little secret:

For the most part, audiences in 1926 and 1927 enjoyed the movie.

|

|

What was that passage from, you ask?

Marion Meade, Buster Keaton: Cut to the Chase (NY: HarperCollins,

1 October 1995, pp. 169, 171–173).

I placed an order for the book immediately, but an acquaintance received his copy before mine arrived,

and he said he was surprised to learn from it that Buster was illiterate.

What???????

Buster was a Morse Code specialist in WWI, and the army did not give that job to illiterates.

That’s sort of like saying that Einstein never learned his multiplication tables.

What was I in for?

Well, I was nonetheless excited to get the book hot off the press, and then I was horrified by what I read.

I was already familiar with many (many, many) of the stories in that book,

but the way Meade retold those stories was fractional.

She would take a lovely example of affectionate behavior,

chop it and carve it and leave out so many details that she reversed the meaning of the story;

what had been a pleasant anecdote thus became a horror story of callous and abject cruelty.

When you know the true stories, you recognize things that the average reader would entirely miss.

Page 113: Meade mentions the

|

|

What continues to amaze me about Buster Keaton: Cut to the Chase is the energy required

to spin almost every last detail, on every last page, in order to cast a shadow on it.

That requires a special sort of innate skill, which in turn requires a special kind of mind,

a special kind of temperament, a special kind of attitude,

a marvelously toxic blend that I have occasionally witnessed in others and which I am grateful I do not share.

It puts me in mind of political propaganda: too easy to believe and too laborious to rebut.

|

|

To my slight surprise and to my great dismay, I discover that even now, today, as I type this,

there are Busterphiles who openly state that,

“Despite its shortcomings, Meade’s meticulous research is evident throughout the book.”

Meticulous research?

My response: It’s “meticulously research”

rivals that of the Weekly World News or “Fox and Friends.”

Meade’s errors overwhelm every last page of the text.

Yes, Meade gathered lots of documentation and she interviewed plenty of people,

but I don’t know why she bothered, since the result was just her spin.

The errors consist of small details as well as major episodes,

the errors consist of tiny nuances and of the whole premise,

the errors consist of conjectural reconstructions and claims of motivations and the basics of every story it contains.

What’s more, the book completely misconstrues Buster’s personality and character.

When we strike through all the errors, we are left with maybe two pages of factual statements.

Okay, maybe three pages, but not more.

Furthermore, those few true statements can easily be found in prior sources.

As for original material, there are maybe four or five sentences that seem to have the ring of truth,

but why should I give those four or five sentences any credence at all

when the rest of the book has no credibility whatsoever?

It is a horrible book that makes absolutely no contribution to the scholarship.

Dardis had set scholarship back, and then Meade set scholarship even further back.

Instead of adding to the knowledge base, they just contaminated the record,

and their spurious claims have infected probably every subsequent book on the topic.

Now we are stuck with the unfortunate task of repairing their damage, and that is by no means an easy task.

By no means an easy task, and by no means a task that most would ever forgive.

We are all taught to be polite, not to engage in polemics, not to go on the attack,

to refrain from criticizing even those who themselves engage in attacks.

“If you can’t say something nice, don’t say anything at all” is what we are taught from earliest childhood.

The situation is made all the more difficult when casual fans who are not familiar with the obscure century-old sources

assume that those of us who object to Meade and Dardis do so simply because they reveal uncomfortable truths.

For the life of me, I do not know how to communicate across that divide.

|

|

It would be much more desirable to present the research with the full panoply of references and exhibits,

and to make no mention at all of the misinformation that has been so widely disseminated.

Unfortunately, to do the sensible thing would lead to a worse problem:

Readers who are steeped in the misinformation would dismiss proper research for being contrary

to the

|

|

Thanks to those two writers,

whenever we make a discovery, we now have to spend too much time defending our work by refuting Dardis’s and Meade’s misinformation,

as I am doing here, and it ain’t no fun, believe you me.

It is astonishing to me that those two managed to fool nearly everyone.

If any good can come of the mess that those two authors made, it should be to make us all question

how much other “information” and “scholarship” and “meticulous research”

about other topics is no better than what Dardis and Meade produced, and how much we are all being fooled, collectively, worldwide.

Now there’s talk about turning Meade’s book into a movie?????

If that happens, it will be worse than the biopic from 1957, about which more below.

The 1957 biopic was gawdawful and had nothing to do with Buster’s life

apart from getting his name right, but it was not mean-spirited.

Meade’s book was extremely mean-spirited and downright vile.

The great thing about a movie like this is that people will see it only on opening weekend

and by Monday morning will not remember having seen it.

|

|

It was when The Day Buster Smiled was published that I had an epiphany.

If audiences and critics were so indifferent or hostile, then how explain the ecstatic review and

thunderous audience reaction when the preview print played at the Alex in Glendale?

Once I read that, I really began to have my doubts about Dardis.

I had never liked his book, since it was so cockeyed and tendentious,

but I didn’t think he was wrong about everything.

Well, now I began to suspect he was wrong about everything.

That is when I began seriously to wonder about what had only briefly crossed my mind back in 1979:

two numbers,

(p. 145): $415,232 negative cost

and what Dardis claimed was a “domestic gross” of $474,264, which looked for all the world like rentals, not gross.

More recently, now that various services offer

|

|

Published statements:

|

|

Wikipedia: “At the time of its initial release, The General...

was not well received by critics and audiences, resulting in mediocre box office returns

(about half a million dollars domestically, and approximately one million worldwide).

Because of its then-huge budget ($750,000 supplied by Metro chief Joseph Schenck)

and failure to turn a significant profit,

Keaton lost his independence as a filmmaker and was forced into a restrictive deal with Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer.”

The San Francisco Silent Film Festival: “...in 1926, it was not so well received.

It faced harsh reviews and slow attendance, and thanks to a budget larger than any previous Keaton feature, it lost money.”

Britannica: “...his American Civil War comedy, The General (1927),

was a financial disappointment when originally released....”

AFI Catalog of Feature Films:

“According to modern sources, the film was not financial success.... contemporary reviews were mixed....”

Senses of Cinema:

“Although it stands as one of the great works of the 20th century, The General was a failure commercially.”

Joanna E. Rapf, Buster Keaton: A Bio-Bibliography (Westport, CT: Greenwood Press, 1995), p. 24:

“...The General took over a year to shoot

and went way over budget. He used real old engines and insisted that they

be fueled with wood (causing the forest fire mentioned above)....

The film was not well-reviewed and was a financial disaster for Schenck and United Artists....”

Edward McPherson, Buster Keaton: Tempest in a Flat Hat (NY: Newmarket Press, 2004), pp. 187–188:

“Buster thought he had his best picture ever. The public, and reviewers,

told him he had a flop — and, having cost a staggering $750,000,

a pricey one at that.16 The film premiered in Tokyo just before the

New Year; it was in New York by February 1927, and in California a

month later.17 The New York Times felt Buster had overextended himself —

it seemed to prefer the short Soaring Wings (also showing),

which featured slow-motion sequences of flying birds. Variety thought

the locomotive chase too long; there was too much Keaton; the film

was unfunny, not fit for quality theaters. In Life, the influential Robert

Sherwood accused Buster of clowning in poor taste — Sherwood

found no comedy in soldiers dying.18 Of all his films, Keaton forever

would be most proud of The General.19 For a long time, he was the

only one.

“Much has been made over the disappointment of The General.

History has revived the film as a masterpiece; the darling of all-time-greatest lists — comedic or otherwise —

The General is Buster’s

best-known film today. For the audiences of 1927, perhaps it was a

case of false expectations. Keaton was becoming a clown who didn’t

do slapstick — while on location in Oregon he had told the local paper

that that stuff was dead — and the film he turned out wasn’t exactly a

laugh riot.20 It is a wickedly funny movie that has dangerously few

yuks. The comedy and drama ebb and flow, the film’s subtle cadence

driving both, favoring neither, something beautifully new. The race

of the dueling locomotives is a high-speed chase that is gentle and

personal — an unexpected, intricate mix. Public accolades would have

to wait.”

Chris Wade, Buster Keaton: The Later Years (Wisdom Twins Books, 2018), pp. 51–52:

“Though The General was only a modest hit upon release,

making a million back on a staggering — for the time — $750,000

budget, it also failed to impress the critics, who for some

reason wrote the film off as inconsequential and unimportant....

Research reveals that there are hardly any positive contemporary notices for

The General. The rejection dinted Keaton’s self confidence and sense

of judgement.”

Imogen Sara Smith, Buster Keaton: The Persistence of Comedy (Gambit: 2008, 2013), p. 164:

“Most reviewers found The General dull, pretentious,

unoriginal and unfunny.... In fact, critics and audiences alike grew cooler towards

Keaton the more he matured as an artist....”

Kristin Hunt, “What Drove Buster Keaton to Try a Civil War Comedy?,”

Take Two, 2 July 2020:

“The reviews for The General were grim, calling the movie a flop and the worst of Keaton’s work....

It’s no accident that The General was mentioned in the same breath

as D. W. Griffith’s blockbuster [The Birth of a Nation].

Both films told a skewed version of history that favored the Confederacy,

whitewashing or justifying its violent racism as perversely heroic.

For Griffith, whose father was a Confederate colonel, this was a deeply personal matter.

But Keaton was no son of the South.

The comedian was born in Kansas, to two Yankee parents.

Yet he had accepted the revisionist account of the Civil War

that Confederate groups had worked so hard to push into the mainstream,

revealing just how pervasive the Lost Cause myth had become by the twentieth century....”

Dana Stevens, Camera Man (NY: Atria Books, 2022), pp. 192, 199:

“...In fact, the historical event was far bloodier

than in Keaton’s retelling. The ten Confederate soldiers who conspired

to hijack a train to slow the progress of the Union army (in the film, the

sides are reversed) were all sentenced to death by hanging....

The General was considered an expensive bomb when it came out in

early 1927.... But most reviewers

converged on the opinion of the New York Times’s Mordaunt Hall, a

reliable marker of consensus taste, that The General was ‘by no means

so good as Mr. Keaton’s previous efforts.’”

Philip Kemp, in the booklet accompanying the Eureka “Masters of Cinema”

Craig Hammill and City of Los Ángeles Councilmember Mitch O’Farrell,

“Cinema 35 — The General (1926),”

LA CityView35 (30 October 2021):

HAMMILL: “...the thing that I always love to bring up,

probably to the point of making everybody roll their eyes who’s been around me long enough,

is that The General, at the time of its release, was considered mediocre and a flop,

and it was the movie that resulted, sadly, in Buster Keaton losing all of his creative freedom.

And why do you think it is that sometimes great movies, at the time of the release, sort of pass unnoticed and uncelebrated,

and then, for some reason, five or ten years later everybody does a double take and says, ‘Wait, we missed it!’

What do you think that’s about?

Because it happens all the time.”

O’FARRELL: “It does.

I have to believe it’s because the films are in some way or another literally ahead of their times, right?

And Buster Keaton was such a genius that, uh, perhaps his contemporaries just didn’t get it....”

James Curtis, Buster Keaton: A Filmmaker’s Life (NY: Alfred A. Knopf, 2022), p. 318:

“Keaton rarely spoke of the critical drubbing he took for The General.”

|

|

Not a scrap of original research.

Well, there was one single scrap of original research, but it was hardly adequate.

Kristin Hunt found one more review, a rave from Chattanooga,

which she proferred as a unique exception to the overall hostility and which she twisted into a conclusion that Buster was

“whitewashing or justifying its [the Confederacy’s] violent racism as perversely heroic.”

That is a particularly irksome, thoroughly untrue, and downright offensive misinterpretation.

Alas, it’s also downright predictable.

Currently, many of our owners are stoking the flames of hatred,

and it is inevitable that, in our present social context,

a story about Confederates now comes across as seditious support of the Confederacy.

That is our tragedy, and we need to do something about it, and quickly.

If we don’t, we’ll have even more riots in the streets,

and that is something I most definitely do not want to witness.

As for Dana Stevens’s assertion that in real life it was Confederate soldiers who hijacked a Union train,

well, I don’t know what history books she was reading,

but they were certainly not any history books that I have ever encountered.

It was Union military and volunteers who hijacked a Confederate train.

Their mission failed, they were caught, and many but not all were hanged (unforgiveably disproportionate punishment).

The best-known book on the topic was by one of the Northern raiders, William Pittenger,

who related the story as he witnessed it.

Buster recognized that it would be more effective, dramatically and comically,

to tell the story from the Southern engineer’s perspective.

By the way, after the war, the surviving Union Raiders

and the Confederate conductor who chased after them, William Fuller, became fast friends.

|

|

All of this, and much more besides, stems from a single page in Dardis’s horrid book,

which was further exaggerated in Meade’s horrid book.

Dardis did little research and misreported his findings.

Meade did even less research and even more misreporting.

Subsequent writers just cribbed Dardis and Meade without factchecking.

Is this unusual?

Hardly.

Pick up pretty much any history book, whether it be about ancient times or modern.

What you’ll find inside is probably no better.

Each historian just cribs from the previous ones, as our history profs teach us all to do.

In an email message to me about a different topic,

a colleague referred to most research as being nothing more than “sloppy regurgitation.”

True. Too true. And, I confess, in past years I was as guilty as anybody else.

This is how history is written, and it gets me down.

I have been collecting reviews of The General and so far I have found 70, of which I reproduce 69

(for the one remaining I provide an external link).

Of those 70, there were 6 that were negative. Another 8 were mixed.

But 56 were positive, some with reservations, and some entirely, enthusiastically, wildly positive.

As I find more reviews, I’ll post them all.

There may have been another 40 or 50 in the US altogether.

I’d be surprised if there were many more than that.

|

|

No scholar has thought to do what I have done above, which is to find the total universe of evidence and to follow it wherever it leads.

Instead, following Dardis’s example, a few modern authors have dug up a little more,

with their laser focus aimed at Dardis’s discoveries rather than at the totality of the evidence.

They pull up exactly the same reviews, verify that Dardis quoted them correctly, and then maybe add back in a few more phrases.

That’s considered factchecking?

These modern authors seem to have discovered that summary from The Film Daily and

thus found a couple more reviews and used them only to shore up Dardis’s thesis;

they did not look at the broader picture.

The result is not only depressing, it is misleading:

|

|

Dorothy Herzog, “The General,”

New York Daily Mirror, 7 February 1927: expensive Civil War monologue... a too-pronounced ‘I’ shaping its destiny... one wearies of the star’s expressionless monologue... being the whole show... jeopardize his popularity... slow, very slow... pull yourself together, Buster. That’s all. |

|

Eileen Creelman, “Comedians and ‘Hamlet’ Complex Again,”

New York Sun, 7 February 1927 This epidemic of drama among the comedies rouses wonder as to The Circus. Will Charlie Chaplin attempt a serio-comic version of Variety or, worse yet, Pagliacci?... one more comedian has felt the bitter sting of ambition and succumbed... to the current epidemic. Buster Keaton, he of the stony face and immobile mouth, has made an historical drama — with comic moments.... As a drama, The General is occasionally exciting, always well timed, often spectacular. As a comedy it offers meager fare.... The General is no triumph as a comedy, but it does not fail as entertainment. Mr. Keaton’s special admirers will probably find him funny anyway. Others may receive enough melodramatic thrills to comfort them.... |

|

Katherine Zimmermann, “Much Ado about Nothing in ‘General,’”

New York Telegram, 7 February 1927 a pretty trite and stodgy piece of screenfare, a rehash, pretentiously garnered of any old two-reel chase comedy.... The audience received ‘The General’ with polite attention, occasionally a laugh, and occasionally a yawn... disappointing... he monopolizes the entire picture with his one-expression countenance.... |

|

“The General,”

New York Daily Telegraph, 7 February 1927 the camera work is good, the settings excellent, the gags among the funniest we have seen — and yet the piece lacks life.... Perhaps the subject itself was too tragic to make the humor unrestrained. |

|

Palmer Smith, “The General,”

New York Evening World, 8 February 1927 tells more of a story, and Keaton develops more of a characterization.... Buster has not learnt to smile. His frozen face is an asset in gag comedy, but when he ventures into character it proves a serious drawback. |

|

“The General,”

New York Herald-Tribune, 8 February 1927 long and tedious — the least funny thing Buster Keaton has ever done. |

|

That seems to be three negative reviews and three mixed,

but I shan’t add them to the tally until I can locate the full reviews.

It seems to me, judging from these brief snippets,

that these particular critics, like Mordaunt Hall, wanted simple slapstick clowning

and resented a straight comedy.

Fine. Different strokes, you know. No big deal.

Yet it is impossible to tell exactly what these reviews really say if we are to judge solely from those tiny snippets.

Even if all six of these pieces prove to be hostile, they would still constitute a small minority of reviews,

the bulk of which were quite positive.

Predictably, modern authors have no interest in the bulk of the other reviews, possibly because they are positive,

but more likely because it would require a bit of effort to find those other reviews.

The few that everybody likes to quote are basically the few that Dardis already quoted.

That makes an investigation really simple.

Instead of spending months or years digging through libraries and archives

and spending inordinate amounts of money to get access to online newspapers and inordinate amounts of time in usually fruitless searches,

all you have to do is retype two paragraphs on page 144.

Much easier, right?

Why do all that work if Dardis already provided you an erroneous summary?

Crib and crib again and crib the crib of a crib.

That’s what our profs do, and so we can do it, too, right?

As we saw above, a few modern authors stumbled upon a couple more reviews,

which I presume they found in NYPL’s vertical file.

I suppose they then began the process of emailing their few discoveries back and forth among themselves,

thus participating in a cult ritual upon which initiates have bestowed the ceremonial appellation “research.”

With this web essay, I hope eventually to make all the contemporary reviews available at a click,

and then nobody will have a valid excuse.

Instead, modern authors will scuttle about in search of invalid excuses.

|

|

As far as I know, no modern author has even attempted to look up the following reviews

(which I have yet to find, but I shall, I shall, I most definitely shall — if they still exist):

|

|

Rochester Evening Journal and Post Express, circa 3 January 1927:

Kept Eastman audiences laughing all the way through. |

|

New York American, circa 7 February 1927

Keaton comedy grips fans.... will please Buster Keaton’s fans, for it contains much first-rate entertainment. |

|

New York Evening Graphic, circa 7 February 1927

No effort was spared to give Buster an authentic background for his reels of antics and the result is worth seeing. |

|

The Atlanta Georgian, circa 14 February 1927: