Harvard University Film Foundation

Oh mercy!

This confuses me so much!

David Pierce

tells us to take a look at Joseph Kennedy’s volume,

The Story of the Films:

As Told by Leaders of the Industry to the Students of the Graduate School of Business Administration,

George F. Baker Foundation, Harvard University

(Chicago and NY: A.W. Shaw, 1927).

Every January, a committee consisting of Harvard faculty would select among the made-in-the-USA films of the previous twelve months

“those films which are deemed worthy of preservation as works of art.”

The selections would be announced each March.

If possible, “two positives of every film selected” would be deposited at the new Harvard Film Library.

Among the 13 films selected that first year was The General.

Then, after that first batch of donations, nothing further was forthcoming.

I assume that at least one of each pair of positives was actually a lavender.

Just an assumption.

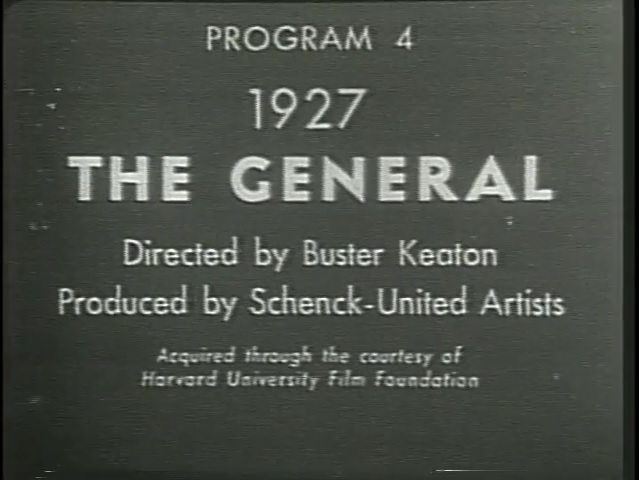

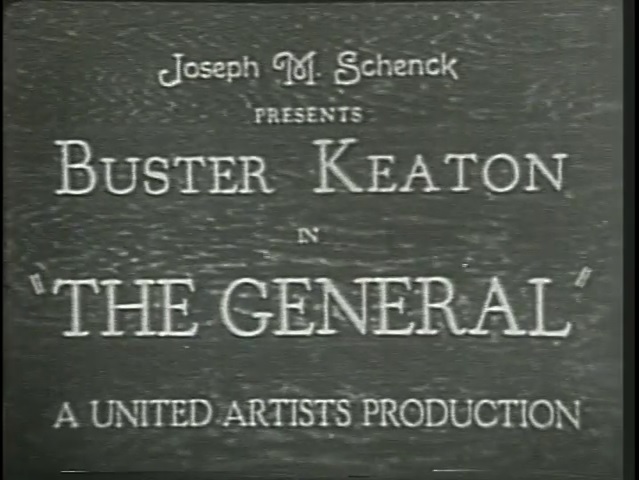

When we watch various video editions of The General,

we notice that some of them open thus:

“Acquired through the courtesy of Harvard University Film Foundation.”

Acquired by whom?

The Museum of Modern Art.

As we shall see shortly, MoMA’s 16mm circulating prints opened differently.

The Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) Revives Some Buster Keaton Movies

I spent many months scratching my head, trying to make sense of this.

And when I finally thought I had the basics figured out,

Ed Watz, in an aside, proved me totally wrong.

So I tried it again, and then David Pierce made a post that demolished even my rewrite.

Let me try this yet again.

It was in 1933 that the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) founded its motion-picture library.

For the first two or three years, MoMA simply convinced the studios to sell release prints that were no longer needed.

That is probably how MoMA acquired Our Hospitality and Go West.

There had been duplicating films from Kodak going back to the mid-1920’s , and they gave rather good results.

Prior to this, attempts to duplicate film were inevitably grainy and smeary, entirely unacceptable.

The new duplicating-positive (colloquially “lavender”) and duplicating-negative stocks were a tremendous technological advance.

These new stocks allowed the camera negative to be printed to a low-contrast fine-grain positive that, in turn,

could be used to produced a copy negative of passable quality.

Then, in 1936, Kodak performed a miracle, and it was a game-changer.

Kodak released its new improved “lavender,” Eastman Fine-Grain Duplicating Film 1365.

This resulted in more than passable quality, actually quite fine quality.

Once the 1365 was introduced, MoMA would purchase lavenders instead of prints,

and it certainly purchased lavenders of

Sherlock Jr. and

The Navigator.

David Pierce informs us

that in 1935, MoMA asked if Harvard would be interested in donating its copies of those 13 movies.

Harvard agreed, and in 1936 those movies were on file at MoMA.

In

1941, to cater to the new private film clubs that were sprouting up all over the country,

MoMA made 16mm circulating prints of any films for which it had lavenders,

and that is how Sherlock Jr. and The Navigator were made available.

The General was also made available,

and that is why I conjectured above that at least one of each pair of positives at Harvard

must have been a lavender.

MoMA did not purchase any other Buster movies, for the simple reason that funds were limited (per Ed Watz).

My guess is that the studios agreed to share their intellectual property

only because those particular films were by then considered worthless.

The studios had zero intention of ever reissuing them.

MoMA probably made a single 35mm nitrate print of Sherlock Jr. and The Navigator for in-house use.

The 16mm print of The General, by the way, appears to have been mounted onto

three 1,200 reels.

MoMA offered those 16mm prints to libraries and film clubs and other nonprofit organizations,

and untrained projectionists operating subpar machines

battered those prints.

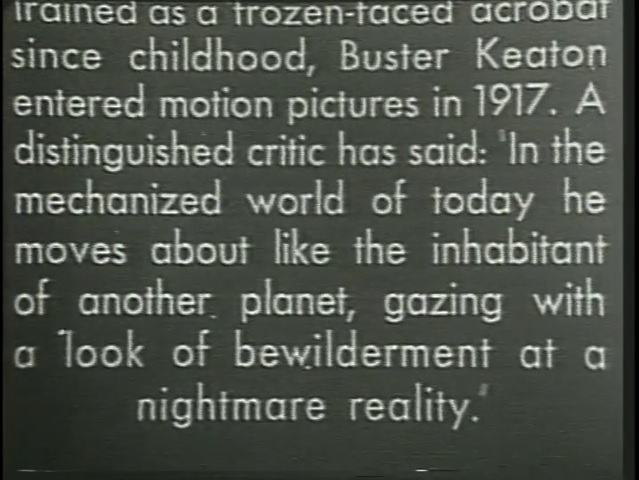

Thus did a new generation discover Keaton and proclaim him a genius,

a description Buster sincerely rejected.

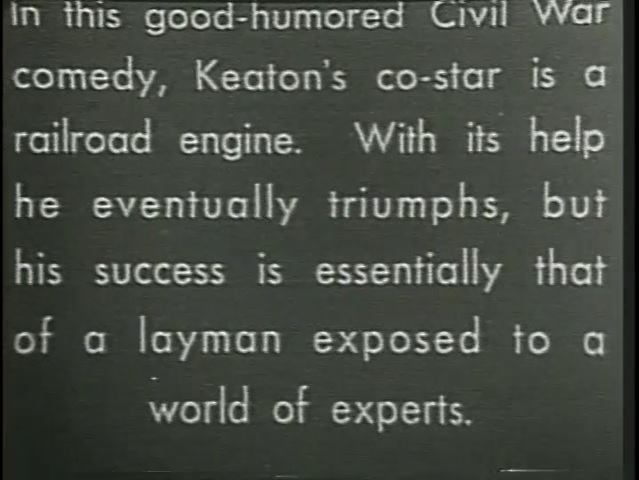

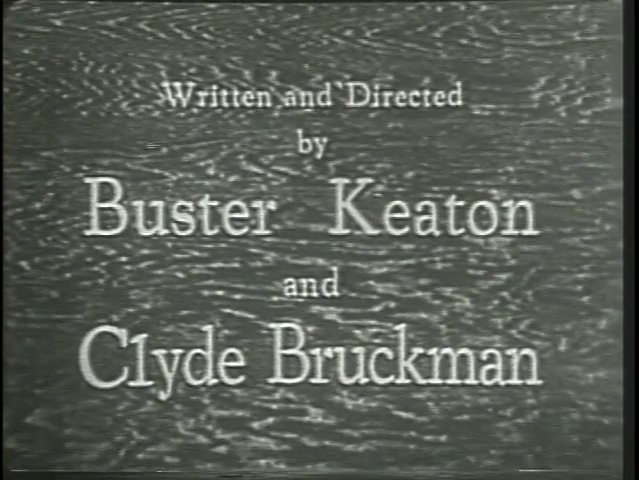

Here is how MoMA’s 16mm circulating prints opened:

This title replaced the original main title.

Kiddie Matinées in London

Oy. I find out now, only after it’s too late.

According to Wikipedia, Gerald Potterton was born in 1931 in London and began to attend Saturday-morning kiddie shows at age five,

which would have been in 1936.

According to Gare Joyce,

“The Railrodder:

Silent Film Star Buster Keaton Drove the Last Spike in His Movie Career with a Tragicomic Cross-Canada Journey,”

The Keaton Chronicle, April–May 2022:

|

The General played a significant role in Gerald Potterton

falling in love with the movies in the days before the

Second World War. “I remember watching Buster’s movies —

it would have been about 1938, 1939 in south London,

where I grew up, at the Odeon,” said Potterton, interviewed

at the age of

|

Jaw-dropping. That means that, as recently as 1939, London cinemas,

or at least at the Odeon in South London

(which I assume was the Odeon Streatham),

was still booking prints of Buster Keaton’s silent movies,

including The General!!!!!

Those prints were over a decade old.

I am amazed.

Intrigued, I hopped onto Newspapers.com in the hopes of finding advertisements or announcements,

but, alas, there was nothing.

Of course, Newspapers.com has only a small selection of British newspapers of the time,

but I was hoping against hope.

In all likelihood, though, these matinées were never advertised.

I suppose that there was a sandwich board on the pavement out front

and maybe an announcement on the marquee,

perhaps even a hand-drawn broadside in a poster window,

but I doubt there would have been more than that.

This gets awfully difficult to trace.

The distributor of The General was still certainly Allied Artists,

which was the London office of United Artists.

As for L&H, their films were still in release at the time,

and so reruns at kiddie matinées should not be surprising.

As for the Chaplin flicks, those were likely the Van Beuren editions

of his dozen shorts for the Mutual Film Corporation,

with those wonderful scores

compiled and arranged by Winston Sharples and Gene Rodemich

with sound effects by the Van Beuren cartoon crew.

I wish they had also scored Buster’s movies, but, sigh, ’twas not to be.

Of course, Van Beuren’s editions were withdrawn in 1937 when the company closed down, but that was in the US.

Perhaps outside the US the distributors were able to extend the contracts through the receivers?

Four of the Van Beuren Chaplins were combined for The Charlie Chaplin Carnival in 1938.

Is that perhaps what Potterton saw?

There is a fair chance that among the Chaplins were also the six Keystone productions that Exhibitors’ Pictures Corporation reissued in 1930,

which remained in distribution for some years and which had scores I have never heard and know nothing about.

There is an even better chance that among the Chaplin films were a dozen of the shorts he made for Essanay,

which Exhibitors’ Pictures Corporation issued under a DBA called King of Comedy Film Corp. in 1939,

stretch printed and again with scores I have never heard and know nothing about.

Further, there was an Edwin G. O’Brien and something called Producers Laboratories, Inc.

(1600 Broadway, NYC),

who from maybe the 1930’s through maybe the 1950’s

were distributing several of Charlie’s Essanay shorts.

Charles Harry Tarbox

(28 June 1903, Fredonia NY – 19 December 1984, Los Ángeles CA)

This is another puzzle.

Charles Tarbox opened his business in 1916, when he was but a mere lad of 13.

He called it Film Classic Exchange and he rented and sold 16mm and later 8mm copies of Hollywood movies, among various other movie oddities.

Early on he worked out of Buffalo, in rented space inside a film exchange on Pearl Street.

Then he moved to Dunkirk, NY, and later still to Los Ángeles,

which, for me, personally, makes his story all the more curious.

The Reverend Thomas Dixon and Epoch sued him for pirating The Birth of a Nation

and later on Harold Lloyd sued him for selling excerpts from Safety Last without authorization.

Predictably, Tarbox was a lawyer.

At some time, he somehow managed to get a 16mm copy of MoMA’s 35mm screening print, the one that opens with a credit to Harvard University.

Did that happen in 1936? In 1984? Sometime in between?

I don’t know.

My current working hypothesis is that he acquired this film in about 1980.

How can you tell if you’re watching a Charles Tarbox print or a copy thereof?

And that’s how you know that you’re watching a Charles Tarbox print or a copy thereof.

Who else would ever tell you these things, now, really? Who else?

Back to MoMA

Richard J. Anobile’s photonovel includes a transcript of Ray Rohauer’s on-stage interview

with Marion Mack in Toronto on 18 December 1972.

Marion mentioned that when the movie opened (she surely meant at the Metropolitan in Los Ángeles, 11–17 March 1927),

she and her husband purchased tickets to watch it.

She went on to say,

“And in later years, every once in a while I used to go to one of the revival theaters

when THE GENERAL was showing.

At first I used to tell them I was the co-star , but I think they either didn’t believe me,

or it meant nothing to them.”

What revival theatres?

The first revival houses appeared in 1960, and in the US The General was not available commercially until 1970.

So, what was Marion talking about?

She could only have been referring to film societies and university film clubs and museums

that, beginning in 1941, booked MoMA’s 16mm print.

Well, now, wait a minute.

I’m scolding myself.

I can think of two revival houses that opened prior to 1960.

Old Time Movies, later renamed the Silent Movie Theatre, opened at 611 North Fairfax Avenue in Los Ángeles in 1942.

The Flicker Silent Movie at 6726 Hollywood Boulevard in Hollywood ran from September 1949 and closed in August 1950.

It’s probably impossible to check their schedules, since they seldom advertised.

Did either of those somehow conjure up a print of The General?

I doubt it.

If they did, where did they get it?

By the time that the film societies were beginning to sprout, accompanists as a species were extinct.

As far as I can determine, film societies presented silent films dead silent, with no music at all.

MoMA, of course, had staff pianists who accompanied, among them Arthur Kleiner,

but MoMA was not a film society; it was a museum supported by the Rockefellers and the CIA.

Among film societies, though, I know of three admirable outliers.

Here is one: