|

ANOTHER SOURCE.

There was a surprise in the Spring 2000 issue of The Keaton Chronicle.

Film historian and preservationist David Shepard wrote a letter to the editor,

which is here quoted in full:

I am working on a video edition of a quite fine Civil War film called The Coward (1915, produced by Thomas Ince, directed by Reginald Barker, starring Frank Keenan and Charles Ray). Eric Beheim, who is doing the music, noticed many startling similarities to the non-locomotive-chase portions of The General. We wonder if this could have been a source for Keaton? Similarities between The Coward and The General (none of these elements was part of the original historical incident): • Confederate recruiting stations figure prominently in the openings of both films. • Failure of the heroes to enlist is used to advance the plot. • When they fall out of favor for “cowardice,” both heroes’ photographs are removed from sight by the family patriarch. • Both heroes overhear a top-level Union staff meeting at which important plans are discussed. • Both heroes hide under the table in the room where the officers are meeting. • Both heroes escape by overpowering guards and changing into enemy uniforms. • During their escapes back to Confederate lines, both heroes are fired upon by friendly sentries because they are wearing the wrong uniform. • Both heroes relay important battle information which ultimately leads to a Confederate victory. • The destruction of a key bridge figures prominently in outcomes of the final battles. For those who are interested, The Coward will be out on DVD and VHS from Image Entertainment later this year as a component of a program of Civil War Films 1911–1915. |

|

The film does make for interesting viewing.

The Coward, forgotten for seventy years, was popular when it was released,

and the few prints continued to meander around the country through sometime in 1917,

when it ran out of steam or, more likely, when the last print wore out.

It is clear that Buster or someone on his crew had been impressed by it,

and it is crystal clear that The General referenced this earlier film, largely for comical effect.

It is also interesting to note that highly decorated war hero Glen Cavender,

who played Captain Anderson in The General,

served as technical director for battle sequences on Ince pictures prior to The Coward,

and that he had worked with Charles Ray.

|

Trivia |

|

CURIOSITIES.

There is a rumor that the general

who gives the command for the engine to cross the burning bridge is Keaton’s former cameraman,

Elgin Lessley.

Wrong!

Kevin Brownlow informs me that it was not Elgin Lessley,

but Buster’s current cameraman, J. Devereaux Jennings!

There is also a rumor that Hilliard Karr appeared in this movie.

No, I don’t think so.

There was a Cottage Grove local who was in the battle scene

who went by the name of “Fat” Kerr.

Now, many people named Kerr pronounce the name exactly the same as Karr.

There was a Hollywood actor named Hilliard Karr whose screen name was “Fat” Karr.

They were not the same person.

The story that Boris Karloff plays one of the three Union generals in the cabin at night

and on the train the next day is incorrect.

Actually, it was Eleanor who got this started.

When she watched the movie, she was surprised to see someone who looked so much like Karloff, and she wondered if it indeed might be he.

It’s easy to see who she was talking about.

The Union general in question does indeed bear some resemblance to Karloff.

Actually, he was

Michael Joseph “Turkey Mike” Donlin,

a retired baseball player who later appeared in vaudeville and was now trying to launch a new career in the movies.

Marion Mack’s character was called Virginia during the main part of the shooting;

by the time they were filming the studio pickups throughout August 1926,

her name was changed to

Annabelle Lee,

surely an homage to Edgar Allen Poe as well as a reference to General Robert E. Lee.

When Johnnie and Annabelle wake up in the woods

|

|

The name also has a curious resonance with a popular song from 1919:

|

|

Oh. You’re wondering. Beatrice Fairfax was the Dear Abby of her day. In 1916, she was the inspiration for a movie serial. |

|

To top that off, Kevin Brownlow, in his book,

Alla ricerca di Buster Keaton,

postulates that the name is inspired by

Johnny Reb.

No need to postulate, as the connection is blatantly

|

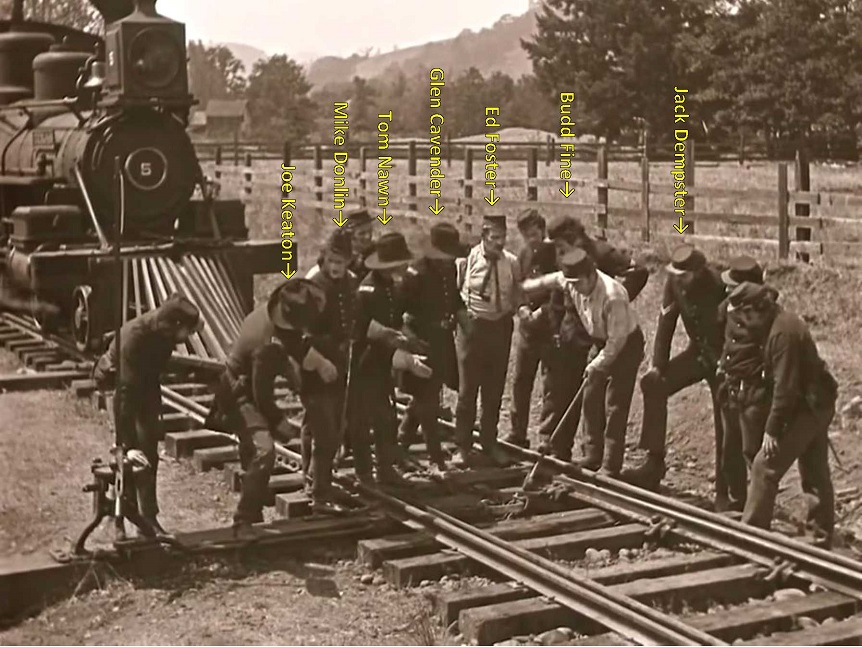

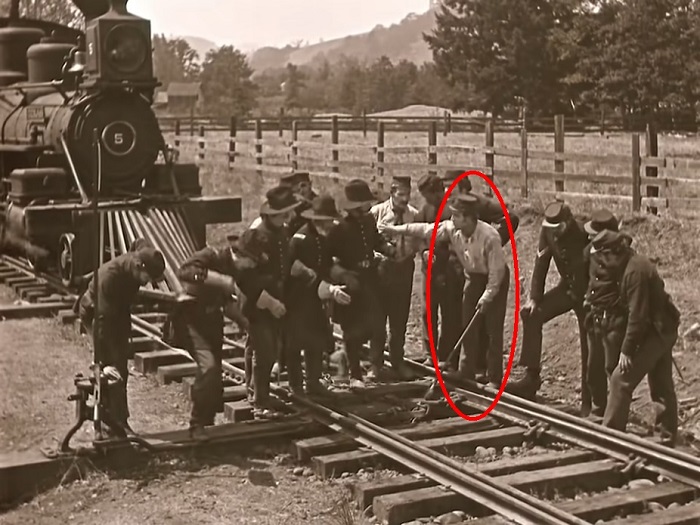

Just to make things nice and sparkling clear: Glen, Tom, Mike, and Joe had all been vaudeville entertainers. Sorry, but the servant who’s washing dishes, I have no clue who he is. Servant, servant, servant, did you think about the servant? Do you ever think about the servant? The Yanks also had their own form of slavery — milder, true, more malleable, true, usually far less cruel, true. We still have that today. Was Buster intentionally making that point? Yes. It wasn’t a major point, but it was there, undoubtedly. |

|

The first time you watch the movie, you recognize that Johnnie and Annabelle are characters.

Everybody else is just a stick figure in the background.

When you watch the movie multiple times, you pick up on a lot of the personalities,

you can figure out what makes them tick.

The guys in the photo above are beautifully thought out, and they really do come across as distinct individuals.

Each raider stands out, really.

So do many of the other extras.

|

|

There is a moment in the movie I do not understand at all.

It is during a chase, as the Northerners are racing up the track to get away from the locomotive that is pursuing them.

The problem with this is that the train is entirely still.

It is not moving at all.

It was not a Hollywood retake.

We can see that it was shot on location inside the actual cab, not in a studio

|

|

|

Other than that obvious mistake, I have but a single quibble with the movie.

That title near the beginning:

“There were two loves in his life. His engine, And — ”

No need for that title.

The movie would have been stronger without it.

I doubt Buster wrote it, but who knows?

I bet that either Boasberg or Smith wrote it,

and Buster probably didn’t feel strongly about it one way or the other and let it in.

Buster certainly edited around that title so that it cannot be deleted without breaking continuity,

and so I guess he was okay with it.

Maybe he even liked it.

But really, I don’t know.

Completely subjective conjecture.

Minor quibble. Not a dealbreaker.

|

|

Here’s something else I don’t understand: The misinformation.

For instance, when we click on the

Film Reference website, we discover this truly odd notation:

“Released 18 December 1926, New York.

Rereleased after 1928 with musical soundtrack and sound effects.

Filmed during 1926 in Oregon.

Cost: $250,000 (estimated).”

Welllllllll, the bit about being filmed in 1926 in Oregon was right.

The rest of it?

I assume that “after 1928” means 1962? Or 1970?

Where did that misinformation come from?

I would love to know who got all that started and why.

|

|

Here’s a head-scratcher.

|

|

|

On the left, Ray Hanford(?) begins to wedge stones between the rail and the guardrail.

On the right, two Raiders begin to uproot a rail, one with a pickaxe and one with the blunt edge of an axe.

There is a third as well (maybe Louis Lewyn?), not too visible in these screen grabs, who is going at it with a crowbar.

In the midst of this operation, the fireman places a piece of wood from the tender over a tie.

Why?

What earthly purpose is that little piece of wood meant to serve?

That piece of wood shifts position twice before magically disappearing altogether.

I’m totally confused.

|

|

Magically disappearing, yes.

Then something reappears: the uprooted rail!

The next morning, three trains glide over this section of track without incident.

To have explained the repair would have distracted from the main drive of the narrative.

And, be honest, you never even thought of that before, did you?

What must have happened in that elision is that soldiers at Kingston,

alerted to the theft of the General, ran back to inspect the tracks and to repair any damage.

After all, the Raiders had made the hurried mistake of simply dumping the uprooted rail into the weeds

rather than loading it into their boxcar to prevent reassembly.

|

|

|

Yes, the above would derail a train.

If the locomotive hits the tie, the tie would pivot and knock the rail out of position,

and then tumble down boom boom oops.

What I don’t understand is the panic over loose items on the rails,

which I would suppose the pilot (cowcatcher) would simply shunt out of the way.

|

|

|

Shouldn’t the pilot (cowcatcher) just plough through all this debris?

What am I missing?

What do I not know?

My only guess, which I am willing to wager one dollar is wrong,

is that the soldiers feared a boobytrap mixed in with that debris.

Anyway, I confess, I have never been an engine driver me with a chuffchuffchuff,

and so there’s a great deal I don’t know.

|

|

One other thing I don’t understand:

Where, when, how, and from whom did Buster receive all his experience of railroad engineering?

We know that in vaudeville he was on trains at least every Sunday for nine months of every year.

My guess is that, when he was a little tyke, he chatted up the engineers and convinced them to let him throttle the trains through railroad yards.

My guess is that, during his youthful summers in Muskegon, he horsed around with trains that were parked at the yards

and probably even took them on joy rides, with the engineers watching over him in amusement.

The two little boys at the beginning of The General are probably an autobiographical element.

When he got to Cottage Grove at age 30, he hired a local engineer to teach him even more.

My guess is that the engineer he hired also portrayed Johnnie Gray’s fireman,

and I am sure he was hired not just to appear on camera, but to lend a helping hand throughout.

Wild guess: Was the fireman portrayed by Del Springsteen or Glen Stevens?

Does anybody know?

Del and Glen worked as fireman and engineer during the first day of shooting in Dallas, on the over-and-under trestle,

but they were not visible on camera.

Delbert Samuel Springsteen, railway lineman, b. 13 December 1896, String River, MN; d. 27 January 1974, Portland, OR.

As for Glen Stevens, he was actually

Samuel Glenn Stevens, b. 23 April 1880, Chippewa Falls, WI; d. 21 April 1950, Salem, OR.

Here he is on

Ancestry.com.

No photos of either Del or Glenn, darn it!

So I rethink my thought: I wonder if Del portrayed Johnnie’s fireman.

|

|

|

Even with all that in the background, though, there was something else going on.

Buster’s agility not only at running over the tops of the moving boxcars,

but also at precipitously balancing himself on the pilot, is quite remarkable, especially when we see him nearly slide off.

It looks like that could have been the end of him, but now that I have watched that moment innumerable times, I see how he did it.

Dangerous, but not quite as dangerous as it looks.

(I sure as heck would never try it, though.)

That is not the sort of skill that a local engineer could have taught him in a few weeks.

My further guess is that, when he was a kid on summer vacations in Muskegon,

he pretended to be a hobo and jumped trains, just for the thrill of it all.

That must have been how he learned the skills of performing

something resembling acrobatics while balancing on the outsides of trains.

I wish we knew the story, but there is nobody left to ask.

|

|

Now, I want you to watch something, a moment from one of the last movies he ever made,

Buster Keaton Rides Again.

Between scenes, he performed a gag, just for the heck of it.

He does not perform it perfectly, but darned near.

It is a gag that probably nobody else on earth at any time in history has been able to do.

It is a gag he could only have taught himself in early childhood.

|

|

|

|

You would not be able to do that, would you?

No amount of practice would enable you to do that, would it?

This is among the many reasons I am convinced that Buster,

in earliest childhood, played around with trains at the local yards.

|

|

|

|

How did Buster not kill himself on the pilot?

He practiced.

He set the engine running in slow motion and spent maybe 30 minutes practicing walking onto the pilot and balancing himself.

He practiced different steps onto the pilot.

He practiced jumping onto the pilot.

When he got comfortable, he tried it at different angles.

He would turn to his side.

He would turn his back to the approaching engine.

When he got comfortable with that,

he practiced plucking the tie from the tracks.

When he got accustomed to the bulk of the tie,

he practiced walking backwards with it onto the pilot while the engine was standing still.

Finally, once he had practiced enough,

he tried it again with the engine rolling at a snail’s pace.

Once he got the hang of it, he increased the speed a bit.

Once he was ready, he brought in his crew and filmed the stunt.

Do I know this for certain?

No, but how else could he have done it?

Watch carefully how he places his feet and his right hand.

Notice that there is a quick cut to a side angle.

That was taken elsewhere, and he was already on the pilot.

Then it cuts to yet a third shot in a different location.

|

|

And now I feel dumb.

Why do I feel dumb?

Cuz I’m dumb.

But here’s why I really feel dumb.

Buster’s

|

|

Now, I confess, I have never once in my life lifted a railroad tie, nor have I ever attempted to.

Why?

Because I don’t have a bunch of loose railroad ties lying around in my living room, that’s why.

I do not know how to get access to a railroad tie.

I’ve seen them around in people’s gardens.

Some gardeners use old railroad ties to create makeshift plant beds.

The ties seemed to weigh a ton.

Yet the railroad tie that Johnnie plucks from under the rail seems as light as a feather,

and the second railroad tie that he tiddlywinks out of the way seems equally light as a feather.

They were too smooth and they looked like hollow props and they seemed to be hollow props,

but who was I to comment upon this without having direct experience?

So I just left the topic alone.

|

|

Now along comes Keaton Talmadge who made me ashamed that I never commented upon that.

She noticed the

|

|

BusterKeatonVK, The Incredible Stunts of Buster Keaton https://youtu.be/72FQIV-jpEk When YouTube disappears this video, download it. |

|

As we saw in the section on the Mystery Stills,

Buster tried this scene again,

probably a few weeks later,

this time with a real railroad tie,

but he apparently gave up on the idea.

|

K27-168

Vapor is emanating from the engine, which might mean that it is in motion.

Buster’s right foot is dangerously placed.

This was too risky, and so he abandoned the idea of improving the earlier scene.

|

|

Hyce, Train Expert Reacts to Buster Keaton’s The General When YouTube disappears this video, download it. |

|

|

Johnnie’s fireman, on the right.  The fireman gives Johnnie a lift.  Where did the fireman go? Who’s that clanging the bell?  A conductor signals the engineer.  A second conductor makes an announcement. We can see through the windows that this was shot on location somewhere around Cottage Grove.  The fireman clambers down from the cab.  The first conductor is startled. The fireman, already wearing a bib for lunch, is perplexed.  The fireman, the first conductor, the station master, and the baggage handler.  The Raiders’ fireman on the left. Can anybody identify any of these peeps? |

|

|

The guy I indicate as Ed Foster is, I am almost certain, Ed Foster. |

|

|

This guy, the engineer of the Columbia, who is he? Does anybody know?

For half a century now, I have found him endlessly amusing, but I never learned his identity.

I have a sneaking suspicion he might be Jimmy Bryant, but I really don’t know.

|

|

Kevin also names a Bill Landers, who was a local, not an actor, but the description does me little good:

“BILL LANDERS (‘prominent... of genial countenance’)

played the tall Southern general in recruiting station (Old Post Office).”

Since everybody at the makeshift recruiting station in the old Post Office/General Store is serious,

it is impossible for me to discern which one was generally of genial countenance.

There is no tall Southern general in the recruiting station.

There is a general, out of uniform, but he is Frederick Vroom, the one who tells Frank Hagney not to enlist Johnnie.

The operative words here are “prominent” and “tall.”

Two of the several tall men in that room are somewhat prominent, and each ends up in line behind Johnnie:

|

|

|

|

They are both tall, but only somewhat prominent.

So who is who?

|

|

Kevin was able to get the names of a few more of the locals who had appeared on camera,

but I do not know if they made it into the final cut.

For instance, Kevin learned that a Patton family also appeared on camera,

but who they were and if they survive in the final film, heaven only knows.

Most fascinating, for me, was Ned Binford, 77 years old, who had enlisted at 14 and had fought in the

Battle of Chattanooga,

and who currently was living in Portland.

He had formerly been a slave.

Whether he had fought on the side of the North or of the South, I do not know.

Would love to learn more. Anybody?

If he is in the final film, he is nothing more than a speck in the distance.

There are plenty of black people near the beginning on the streets of Marietta

as the call goes out for volunteers.

Except for one, they are so far away from the camera that it is impossible to make out their faces.

Actually, very few faces, of any complexion, are near enough to the camera to be recognized.

What we see is an anonymous crowd scurrying about.

Watch that busy street scene again, carefully, several times over.

Clyde Bruckman directed it, without any question, and every last one of the countless people on camera had specific directions.

The brief scene registers only as commotion on a first or even a second viewing, but subsequent viewings reveal how marvelously intricate it was.

|

|

Ancestry.com lists

Edward Binford, b. Nov 1848 in Alabama; married

Charity in 1890; father of Edward, b. 18 April 1903.

He is also listed as

Ned Binford (28 Nov 1850 – 16 Mar 1936), husband of Charity Ann.

So little info, so little, little info, but I’m sure they had fascinating stories.

I can only hope that their stories were recorded somewhere.

|

|

SMILES. Critics and audiences alike make such an issue of Buster’s unsmiling visage,

and they see it as a gimmick, which it most definitely was not.

I don’t see what the big deal is.

Look out into any random crowd of people and how many smiles do you see?

Most of the time you will see none at all.

Go to the grocery shop and look at the faces of the customers.

How many are smiling?

None.

When you go back to your office, look at your coworkers to see how many are smiling.

Most of the time, nobody is smiling.

Smiles are for special occasions.

Buster was, mostly, a minimalist.

He would pare a performance and a routine down to the barest basics, and then pare it down even more.

I can easily imagine him telling his actors, “Do less. Do less. Do less.”

The acting in some of his features (1923–1927) is extremely understated, often so understated that it vanishes.

The result is the most convincing performances ever given in Hollywood movies.

When you watch his movies, you will see that almost nobody smiles.

In The General, there are a few brief moments of smiling,

each of them motivated:

|

|

|

The underplaying leads so many people, critics and audiences alike,

to postulate that Buster’s character is “frozen-faced” or “stone-faced,”

though he has many subtle expressions, all the time.

The underplaying leads many to define him as emotionless,

despite the wealth of emotions that is clearly on display in every scene.

(Yet others interpret his character as either sad or grouchy, and I just don’t see that at all.

Yet even others interpret his character as a pessimist. A pessimist?

His character is quick-witted, resourceful, and a problem-solver, the polar opposite of a pessimist.)

The supposed absence of emotion is then further extrapolated to argue that Buster’s movies are just gags,

cold and mechanical gags, pure comedy devoid of heart and soul.

When I hear that, when I read that — and I’ve heard it and read it too many times —

I realize that either everybody else on the planet is seeing something to which I am blind,

or I am seeing something to which everybody else on the planet is blind.

I suspect the latter.

Audiences seem to relate better to Charlie Chaplin and Harold Lloyd, because, I have heard it said numerous times,

they exhibit recognizable emotions.

What I see in Chaplin and Lloyd is overacting.

As much as I love Chaplin and Lloyd, Chaplin’s emotions register, to me, as mawkish and manipulative tug-at-the-heartstrings gimmicks,

and Lloyd’s emotions seem to be the work of someone who has no emotions

but who has been taught to recognize emotional behaviors in others

and has learned how to mimic them in order to blend in.

Except for the adorable Edna Purviance (genuine sparks fly between her and Charlie),

Chaplin’s leading ladies are goddesses to be worshipped.

Lloyd’s leading ladies are trophies to be won by the brash

|

|

A dear friend of mine, who is no longer with us, liked Keaton but adored Chaplin.

He insisted that Buster Keaton had no narrative skill whatsoever, unlike Charlie Chaplin, who was a master storyteller.

He confessed that he liked The General even though it did not have a story.

It was just a series of train gags, nothing more.

Granted, he really liked the train gags, but they were just train gags, not a story.

For a good story, for masterful narrative technique, he sang praises to Chaplin’s City Lights.

He explained that in City Lights, the story all comes together with a touch at the end.

Just a touch, one hand touching another, that masterfully merged all the elements into a single story.

He said there was no such device in The General, which was just a random string of train gags, without rhyme or reason.

That totally puzzled me, and it still does, but I suppose his take is identical to that of many viewers.

Indeed,

an Amazon reviewer named okusock, who I assume saw a pirated and butchered copy of the movie rather than the original,

griped that The General was nothing other than a plotless string of circus-like stunts.

As for City Lights, I can’t see any plot in it to save my life.

I see a consistent theme that is present in every last routine, but not a plot.

It is a string of blackout sketches with a linking device,

a linking device that is not at all convincing.

The General, on the other hand, is story throughout.

Everything that happens in it serves to advance the narrative,

and the two main characters evolve and mature as they are tested by the dramatic trials to which they are submitted.

Yes, there are gags of sorts, but they are the sorts of things that could and would happen in real life.

We don’t laugh because the events are improbable; we laugh because they are too probable.

Every last gag is subsumed to the lean and forceful narrative.

I guess different people have different ways of seeing the world.

|

|

There was even a guy I met through work who said he really liked Buster,

but that Buster had an exact duplicate.

This guy said that he could never tell Buster Keaton and Ben Blue apart.

He said they looked exactly the same, acted exactly the same, and had the identical sense of humor.

It was as though they were the same person.

At the time he told me that, I had never even heard of Ben Blue.

So, I decided to take a look.

Do you see any similarity?

Any similarity at all? Even the tiniest little bit?

I don’t.

I mention this because if one person perceives things this way, then others do as well.

It’s startling to me how differently different people perceive things.

Startling and downright incomprehensible.

|

|

GEOGRAPHY.

I have never visited Georgia or Tennessee.

I hear that they are gorgeous, my type of countryside, surely filled with amphibians whose company I prefer to that of humans.

Though I have never been there, I know for certain that the geography in the movie bears no relationship to the geography of Georgia and Tennessee.

The BFI Guide

to the movie encouraged me to examine some details more closely.

I had noticed all these details before, but I never dwelled upon them — until now.

I love 50% of the BFI Guide’s text, but only 50%.

That little pamphlet got me all mixed up for two days,

and I had to spend time watching parts of the movie again and again and again, comparing screen grabs in order to understand it better.

Then I messed up this web page and had to spend another day repairing it again.

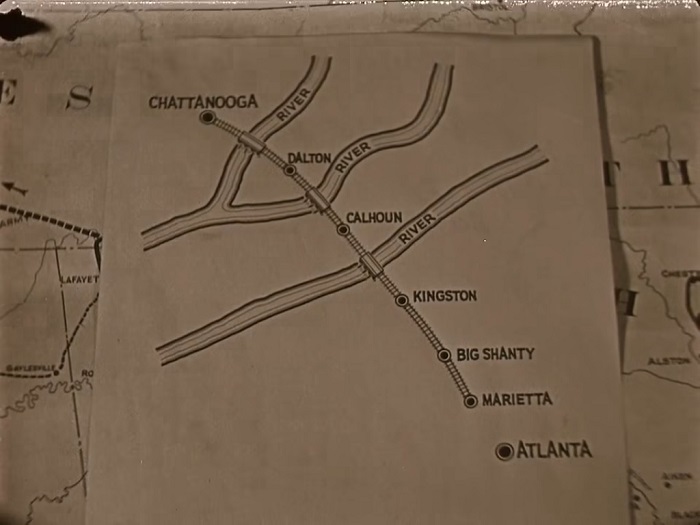

The BFI Guide alerts us to ponder an insert of a rough map:

|

|

|

Now, the map, of course, is a prop.

It is not a depiction of the actual Georgian/Tennessean terrain.

I never had the slightest curiosity about checking it against real maps,

because I realized that it was just a prop, and props aren’t meant to be taken too seriously.

They drive the narrative forward; they don’t correspond to the real world.

Nonetheless, with the BFI Guide in hand, I decided to take the plunge and check the prop against

the real topography.

|

|

The cities and the general line of travel are more or less correct, though greatly simplified, but the other details are just made up.

We see three bridges, each over an unnamed river.

You’ll never find those rivers on a real map.

The apocryphal Rock River, just above Marietta, is not named and not even indicated on this map.

The Raiders, of course, have no interest in the Rock River at this stage of the narrative,

and so there was no need to mark it on the map.

|

|

The BFI Guide got me curious about the several cities named, and so I plugged those places into Google Maps

to learn that the distance from Atlanta to Marietta is about 20 miles.

It’s another 7½ miles to Big Shanty (now called Kennesaw),

29½ more miles to Kingston,

another 20½ miles to Calhoun.

Between Kingston and Calhoun is a river over which there is a railroad bridge.

Apocryphal. On

Google Maps we discover

a tiny stream that empties into the Oothkalooga Creek, but I don’t think that’s what the movie map refers to.

There’s also a smidgin of the

Oothkalooga Creek and

this ankle-deep brook and

this little puddle, but these can’t be what’s on the movie map.

There was no such river, unless a

|

|

From Calhoun it is another 21 miles to Dalton, again with a railroad bridge over a river.

To my amazement, that is correct!!!!!

The

Oostanaula River flows through Resaca, between Calhoun and Dalton,

but it is not the shape shown on the movie’s map.

The coincidence of a real bridge corresponding to the movie map’s bridge is just a coincidence.

There’s

quite an impressive bridge over the Oostanaula, I must say.

There’s another bridge as well, over

Drowning Bear Creek.

|

|

Then Dalton to Chattanooga is another 33½ miles,

again crossing a bridge over a river.

I don’t see a river, but I do see a small bridge over

Mill Creek, and

a second one as well.

There is a third minuscule bridge, too, over

North Fork Mill Creek.

Interestingly, there is still a

Western and Atlantic Railroad Tunnel,

shortly followed by a tiny bridge over

Tanyard Creek.

A little further north we get to a bridge over

South Chickamauga Creek,

which the track crosses

a second time and then

a third time and then

a fourth time.

Then it crosses a bit of

Peavine Creek.

Soon it crosses

South Chickamauga Creek yet again, and that bridge is rather substantial,

and then it crosses it

yet again, again with a rather long bridge.

Then it makes its way above some other

body of shallow water.

Then it’s over

the Mackey Branch,

then over

a rut,

then another

long bridge

over South Chickamauga Creek for the umpteenth time and

then another umpteenth

and finally we’re in Chattanooga. Phew!

|

|

Why did I just spend several nonrecoverable hours of my life doing that?

|

|

So, it seems that the chase northwards, Big Shanty to, presumably, Chattanooga is about 105 miles, give or take.

The chase south, from, presumably, Chattanooga back down to Marietta is 112 miles, give or take.

I have read wildly varying claims in wildly varying sources,

but it seems that the General and its sister woodburners could do about

45mph maximum in ideal conditions, but that

track conditions Georgia and Tennessee were far from ideal.

The trains in the movie were probably moving considerably faster than the ones in the real story.

Maybe. Again, the claims vary so wildly that I am unable to determine the truth of the matter.

|

|

And that leads us to the cities.

We begin in Marietta, but that is not where shooting began.

One of the first sequences shot, as we examined above, was a sequence that Buster abandoned and junked before even completing.

That abandoned middle of the story with the restaurant presumably took place in Chattanooga, though we cannot be sure of that.

Then Buster began again, this time using the outdoor set as Marietta instead.

Then after Johnnie and Annabelle set fire to the Rock River Bridge,

they return to a much-changed Marietta to alert the townsfolk.

These three iterations can leave one with a sense of déjà vu:

|

|

The abandoned middle of the story, presumably in Chattanooga.

This must have been filmed after the bulk of the shooting was completed.

|

|

|

This is the revised opening, when the General arrives in Marietta.

Buster had tried a few other openings in the early days of shooting,

but now, towards the end of location shooting, he junked them all and tried a few more.

This set had originally been built as a small village outside Chattanooga, but before the cameras rolled,

it was slightly remodeled to become Marietta.

Later, it was remodeled again into a small village outside Chattanooga, but that footage was never used,

and then it was remodeled yet again into a rebuilt wartime Marietta.

Note the small train depot on the left.

Note the shops on the right.

We later discover, from the positions of the shadows,

that the right side is unexpectedly the east side of the main street.

Apparently, the track makes a 90° left turn to get into Marietta,

and then, certainly, a 90° right turn to continue down to Atlanta.

Please note the post-and-rail fence and swinging gate in the foreground.

|

|

|

Not long afterwards, the call goes out for volunteers.

Now we know the exact day: the day the South Carolina militia fired upon Fort Sumter,

and that day was Friday, 12 April 1861, at 4:30 in the morning.

It takes a few hours for the news to reach to Marietta.

We can see that the town crier has taken up a position on the balcony of the Town Hall at the end of the street.

Men of draft age walk away from us, northwards, to make a right turn around the block and queue up in front of the makeshift recruiting station.

The slaves head in the opposite direction, towards us, southwards.

(Note that the shadows have not shifted over the past hour or two.)

|

|

Shall we take a better look at the outdoor set?

|

|

|

Why are all these men gathered by the tracks, watching the approaching locomotive, and why are yet more men approaching?

Because the General has been tooting its horn like mad for probably the last mile or two,

to announce to one and all that there is an emergency at hand.

We are back in Marietta, and we see that there have been some dramatic changes over the past year and a day.

We know the day.

The Andrews Raiders stole the General exactly a year after the Fort Sumter battle: Saturday, 12 April 1862,

and, in this fictional story, Johnnie recaptures the General and takes it back to Marietta the following morning.

So, this is Sunday, 13 April 1862, a year and a day after the opening scenes.

The house with the dormers and white trim was only barely visible a year earlier, when it was a Stage Stable.

It still stands, upgraded,

but the shops along the east side of the main street are all gone.

In their place is a C.S. Christian Commission (was there such a thing?),

which functions also as an encampment and a sanatorium.

The old depot now has an addition: a warehouse.

The old building behind it is gone, replaced by the C.S.A. Division Headquarters.

The Town Hall at the end of the street is gone, replaced by a newer, smaller building.

Note that it does not have a gabled roof.

Rather, its roof surely slopes away from us, and on top is a fenced observation platform,

something that might come in handy during troubled times.

Note that the post-and-rail fences and the swinging gate are gone,

and in their place are new snake-rail fences in the foreground.

Note that the trees in the background are mostly identical to those a year and a day earlier.

|

|

|

Return from the Rock River battle.

The shadows have shifted by a few hours, indicating that west, not north, is to the left,

which is contrary to the film’s convention.

The track, I suppose we are to suppose, makes a left turn to get to the Marietta depot.

|

|

Did you notice sumpn?

Half the buildings are identical to what we saw in the opening scene,

but the townsfolk have had a year to demolish, replan, rebuild, in response to the ongoing battles.

These are the sorts of details that need to be put into a movie, even though they are not meant to be noticed.

We in the audience do not notice when things are right.

We notice when things are wrong.

If these details were not added, then we would all notice that the city was surprisingly unaffected by the war,

and such an error would not withstand scrutiny.

The first person Johnnie encounters here

he had previously encountered at the recruiting station a year and a day before: General Vroom.

Before day’s end, he also meets again with Recruiting Officer Hagney.

They were stationed in Marietta a year earlier and they are still stationed there.

By the way, all these buildings, except possibly for one, were just frontages.

They kept toppling over in the breeze and the stagehands had to keep pulling them back up.

|

|

Now it’s time for a great video that has but a single error:

|