The First Preview Screening |

|

Location shooting finished on Saturday afternoon, 18 September 1926.

A month later came the preview, as we discover from Jim Curtis’s new book,

Buster Keaton: A Filmmaker’s Life (NY: Alfred A. Knopf, 2022), p. 307.

That convinced me to see what I could find in the newspapers.

This is confusing, so let’s begin with some background:

|

|

The above advertisement provides us a clue.

The night prior to the test screening of The General,

there were three full showings of

Take It from Me.

Introducing the program was a stage show derived from Fanchon & Marco’s

Wee Bit of Scotch,

and I think we can assume that lasted about 5 or 10 minutes.

There were also three short films:

International News,

Aesop’s Fables, and something called

A Letter from Hollywood.

We do not know how long those short films were,

though they were likely 10 minutes each or a little less.

Now, let’s examine Take It from Me.

According to

Progressive Silent Film List, Take It from Me is 6,649' on seven reels.

How long was that?

In 1926, the usual projection speed was 90'/min, give or take (same as the common speed for talkies).

At 90'/min, 6,649' is about 74 minutes long.

Now, look at the curtain times.

There was a matinée at 2:00, after which the cinema shut down for a few hours.

The evening curtain times were 7:00 and 9:00.

A ha!

That means that the full show was a little less than two hours.

Remember, there has to be a short interval to allow the 7:00 audience to leave

and the 9:00 audience to enter and seat itself.

Say the interval was five minutes, though it was probably a bit more.

Say the three shorts averaged about 10 minutes each, for a total of 30 minutes.

74+30=104.

Say that the band’s piece, presumably with some dancers on stage,

was a further five or, heck, let’s say eight minutes:

104+8=112.

That makes sense. It fits the time slot.

Zo, the point to remember here is that Take It from Me was about 74 minutes long.

That’s the clue we need in order to understand the next day’s misprinted

advertisement.

|

|

What are we to make of all of this?

Take It from Me

was about 74 minutes, and The General, at Buster’s preferred speed of 90'/min, is about 79 minutes.

The preview that starts “promptly at 7 o’clock”

“will get under way at 6:30 o’clock.”

Pretty clear, isn’t it?

I see what happened.

The normal curtain times for Take It from Me were 2:00, 7:00, and 9:00.

The stage act and the shorts were jettisoned for this one night.

The show was to consist of the two features and nothing else.

The curtain times were adjusted to make room for the preview.

Once we understand that, and once we look again at the several announcements,

we can see that, whoever submitted the advertisement simply neglected to adjust the showtimes in the top half of the display ad,

though he (probably he) did adjust the showtimes in the bottom half of the advertisement.

We can work out that the curtain times at the

West Coast Theatre

that day and night were as follows:

|

|

2:00, Take It from Me

6:30, The General, 7:50, Take It from Me 9:15, The General, 10:35, Take It from Me 11:50, close |

|

There was surely no break after The General.

The curtains closed at the end of The General,

but as soon as they closed, they opened again.

As soon as the audience saw THE END fade out, the regular feature commenced.

|

|

Note the claim that The General was 11 reels and would surely be trimmed.

Judging from the curtain times, those were 11 very short reels,

because the length of the film at that preview screening

was almost exactly the same as its current length,

about 79 minutes, give or take, depending upon variables.

We know that Buster wanted The General projected at 90'/minute (same as sound speed), no faster, no slower —

he said as much to Raymond Rohauer,

and that information was eventually transmitted to Kevin Brownlow.

Buster would have insisted on that speed on that preview night,

and 79 minutes or maybe 80 minutes exactly fits the schedule.

Actually, I am pretty sure that the film was half a minute longer than 79 minutes, maybe even a minute longer, on that very first night.

We can see evidence of a few trims in the middles of scenes, which result in slight breaks in continuity.

Those are the give-aways that tell us where Buster tightened the pacing.

Note the statement that,

“The production as shown here

last night was unfolded in 11 reels.

Undoubtedly this will be cut down,

without losing any of the effectiveness,

before it is finally released

throughout the country.”

The anonymous author of that article could not possibly have foreseen the problems his statement would cause nearly a century later.

First of all, yes, the film was cut down prior to release, but by only half a minute or a minute.

The reel count is handy to have, but, as we learned, those were remarkably short reels.

Why did the anonymous author make the point that the film would be “cut down”?

As we shall learn below, The General was announced as a SIX REEL picture,

and six reels cannot hold more than about 68 minutes of film at the very most,

and in most cases six reels hold only about 50 or 55 minutes of film.

It was a United Artists press officer who told the anonymous reviewer that the film would be “cut down,”

because, it seems, United Artists was contracted to ship out a

|

|

If you’re curious to witness The General slowed down to about 67½'/min, or about 18fps,

which is a bit slower than camera speed in most shots,

you can watch the blurry 16mm bootleg of Harvard University’s 35mm print on Archive.org,

but be warned that it has one of the most inappropriate music accompaniments I’ve ever heard.

“Pomp and Circumstance,” good grief!

Harvard’s print was later donated to MoMA.

If you were unfortunate enough to purchase Echo Bridge’s Keaton/Fields DVD,

you are now a proud owner of this abomination.

|

|

What Buster showed that first night was surely not a finished print.

It was also surely not his workprint.

A workprint would have been pretty ragged.

It was a second print, with the shots spliced together by hand,

conformed to his workprint.

As for being assembled onto 11 reels rather than the 8 that would soon carry the release version,

that would make sense, because this was an unfinished print.

Buster had not yet worked out where to have the reel changes,

and, because he was not quite done yet, he kept his workprint (and this second print) rather loose,

with each reel much less than the usual 800 to 1,000 feet,

some of them perhaps 500 feet or even less.

That’s all. Simple. Please don’t overinterpret.

Please please please please please do not say that the preview screenings in San Bernardino

were thirty minutes longer than the current version. Please.

|

|

Tunes. Tunes. Tunes.

I’m thinking again.

Rather, I’m trying to think again.

Oh gawd I hate thinking.

It hurts too much.

Let’s think together, to dissipate the pain somewhat.

The film was likely not dropped off ahead of time.

Buster’s crew likely carried the print in with them that very night.

So, in all likelihood, whoever accompanied the movie had never seen it before.

What does that mean?

That means that an orchestra or ensemble would not accompany the film, because no score had been compiled

and because there had been no opportunity to rehearse.

James C. Bradford would not compile a score until later on, after the final cut was complete.

Zo, since the orchestra would not accompany, it was the organist who was forced to improvise.

The West Coast had a Wurlitzer

|

|

Finally, notice how wildly enthusiastic this review is.

This is as good as a review could possibly get, and it surely exceeded production’s expectations.

So much for the tired old story that the original reviews were all dismissive.

|

|

Since the two audiences were enthusiastic, and since the review was glowing,

Buster was surely now certain that he did not need to make major amendments.

It was probably the next day that he assembled the film onto eight fairly rull reels rather than eleven partially filled reels.

|

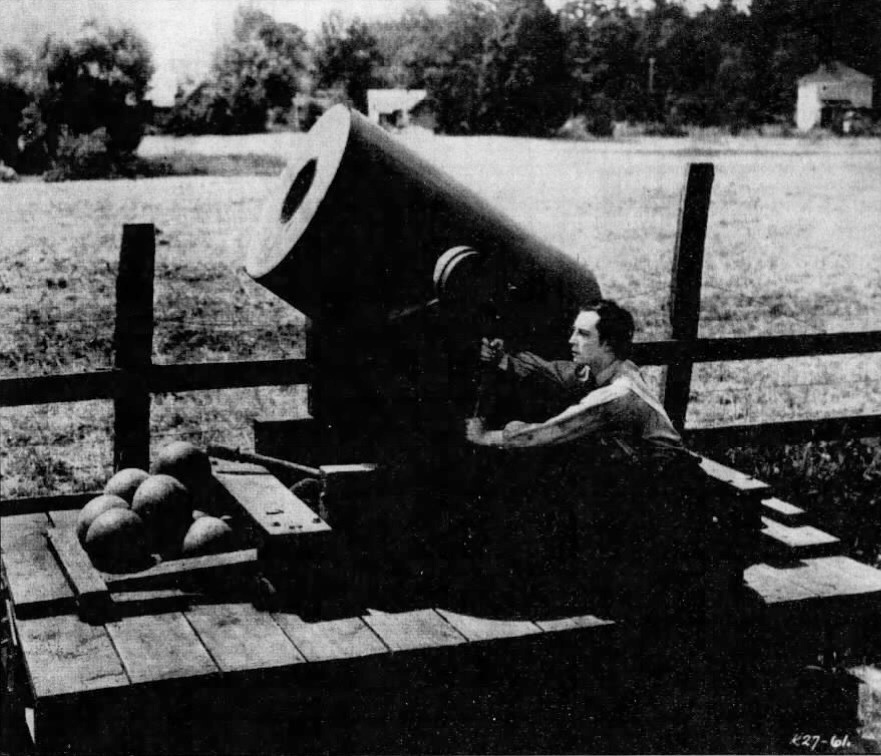

K27-61 (Margaret Herrick Library still # 15) |

K27-76 (Margaret Herrick Library still # 22) |

K27-62 |

K27-66 (Margaret Herrick Library still # 125) |

K27-74 |

K27-63 (Margaret Herrick Library still # 16) |

GC-9 Gag photos. | |

The Second and Third

|

|

The General was given a second test screening in San José, California.

As I mentioned above, my best guess is that by now the film was assembled onto eight reels rather than eleven.

I could be wrong about that.

Maybe Buster was still worried that a second preview would indicate he needed to make major changes,

and so maybe he decided to leave the reels really loose,

but I doubt it.

I really would guess, with quite some confidence, that the film was now packed a little better onto eight reels.

|

|

According to

Simon Braud, this preview screening was at the

California Theatre on 22 October 1926.

Braud quotes a single sentence from the review by Josephine Hughston in the San José Mercury-Herald:

“There is a feeble plot of a sort and considerable rather pointless comedy, although some of it is really funny.”

I would love to see the full review as well as the other local reviews, if any.

(“Feeble”? Why did she say “feeble”?

Because there were no monsters in it? No gangsters? No love triangles? No pie fights? No evil scientists with secret formulas? No cops and robbers?)

|

|

I’ve only passed through San José; I’ve never had the opportunity to spend a few days there.

Well, I guess I have to take the plunge and have my cat and myself spend several days there so that I can delve into the archives.

Simon Braud quoted only a single sentence of a single news item, and nothing more.

I cannot make a good assessment based only on that.

Jim Curtis, on p. 308, offers another little quote from some unreferenced, unidentified news item,

in which Buster was quoted as saying,

“It held an audience. They were interested in it —

from start to finish — and there was enough laughter to satisfy.”

Two tantalizing miniquotes that tell me much less than I need to know.

|

|

Curtis (p. 308) writes something impossible:

|

|

It was around this time that Keaton also made the decision to remove the

sequence, about a third of the way into the film, in which Johnnie goes undercover

in Chattanooga, risking detection and leading to his discovery of the

Northern generals’ plot against the South. Possibly sensing that it slowed

the pace of the story, he covered the elimination with an intertitle, shaving

the running time to just under eighty minutes. In that form, roughly thirty

minutes shorter than the version seen in San Bernardino, he was confident

enough to schedule a third preview at the Alexander Theatre in Glendale....

|

|

Uhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhh, no.

No, no, no, no, no. No.

I don’t know where he got that idea, and he does not have any citations.

It reads to me like guesswork based on previous conjectures spoken

by people who had chanced upon some unit stills but who never researched them.

The sequence to which Jim referred, of course, is the abandoned sequence with Snitz Edwards, detailed below.

It was never included in the movie.

Yes, the implication is that the middle of the film takes place in Chattanooga, but that is nowhere made explicit.

Actually, a local news story, printed at the time that the troupe left the area, revealed the truth:

This exterior street set was “a village on the outskirts of Chattanooga,”

which never appeared in that form in the final film.

Frank Barnes redesigned it to be Main Street in Marietta.

That explanation comes from an unsourced article reprinted in The Day Buster Smiled

(Cottage Grove Historical Society, July 1998), p. 49.

As for the rumors that the restaurant was ever shown to the public,

well, those are incorrect guesses sparked by unresearched materials

that have by now evolved into

|

|

Buster surely made some revisions after the San Bernardino screening

and possibly also after the San José screening, but those revisions were very small indeed.

He tightened his entry into the recruiting office, probably by deleting maybe half a second.

He tightened the bit where he is washing his hands as the train is stolen (the soap now disappears from his hands without explanation).

He tightened the moment when the Northern raiders first see that a Southern train is chasing after them.

He tightened the moment when his foot gets stuck in the safety chain.

He trimmed the shots to make it appear as though he had simply shaken the chain off his foot,

yet clearly there was more between the two shots.

The gag was distracting from the action of escaping from the cannon, and so he cleverly removed it.

He tightened the moment when the Texas nearly goes off an unfinished track.

Originally, he dashed out of the cab and looked around, trying to figure out how the other train got away without using rails.

He snipped that out and got on with the action.

He rearranged some of the shots of Johnnie chopping wood on the tender,

which breaks continuity but improves the flow.

Nobody on a first viewing would notice the impossible continuity.

When he clobbers the Union sentry by the door that night in the rain,

there is a snip as the camera tilts down to get the sentry back into frame.

That snip was probably made prior to the preview, but I can’t be certain of that.

|

|

|

When Johnnie finds a scabbard on the ground after the troops rush off to the Rock River bridge, there is another snip.

Apparently Buster wanted to delete a gag that wasn’t working, or maybe he just didn’t like the pacing.

That may have been snipped prior to the first preview, but I suspect it was snipped just after.

|

|

|

If you watch carefully, you’ll see a few other similar snips in the action,

snips that, altogether, could not have come to more than a minute, and probably totaled much less.

One revision he certainly made was with the scene you all know in which he is on a mock engine

with trees on a scrolling canvas in the background.

Apparently, he didn’t like the performance he had given on location,

and so he

|

A mock-up engine, with trees painted onto a continuous-loop canvas in the studio.

It seems that Buster was about to return to Cottage Grove to retake this shot but then decided against it.

More likely, Joe Schenck and the trustees decided against it,

most likely because the United Artists executives put their collective foot down.

It would have been too much work and too much cost for too little reward.

So Buster let this

|

|

It is possible that another replacement gag was the conclusion of the battle, when Johnnie rescues the Confederate flag.

Perhaps he decided that whatever he had filmed on location did not work.

Did he perhaps film the Northerners in retreat?

If so, that might not have been the most appropriate image to show on movie screens.

Another possibility, I think a stronger possibility, is that the Oregon National Guardsmen

had to return to their base before the battle could be completed.

After all, a brush fire broke out while the battle was being filmed.

The fire had nothing to do with the filming; it occurred some distance away,

but everybody, Guard and cast and crew, dashed out to extinguish the flames.

I suppose that is what canceled the final few shots of the battle scene.

If that is what happened, then Buster invented this nice little grace note to bring the scene to an end.

He shot it when he returned to his 1025 Lillian Way studio.

Whether this was a replacement or an emergency patch, it works as a deflation, as mock heroism.

|

Indoor set, mock hilltop, prop trees. The mountains and sky in the background are painted. Incidentally, the “Stainless Banner” flag seen here did not come into use until May 1863. The Confederate flag in the spring of 1862, the time of this fictional battle, was Nicola Marschall’s |

|

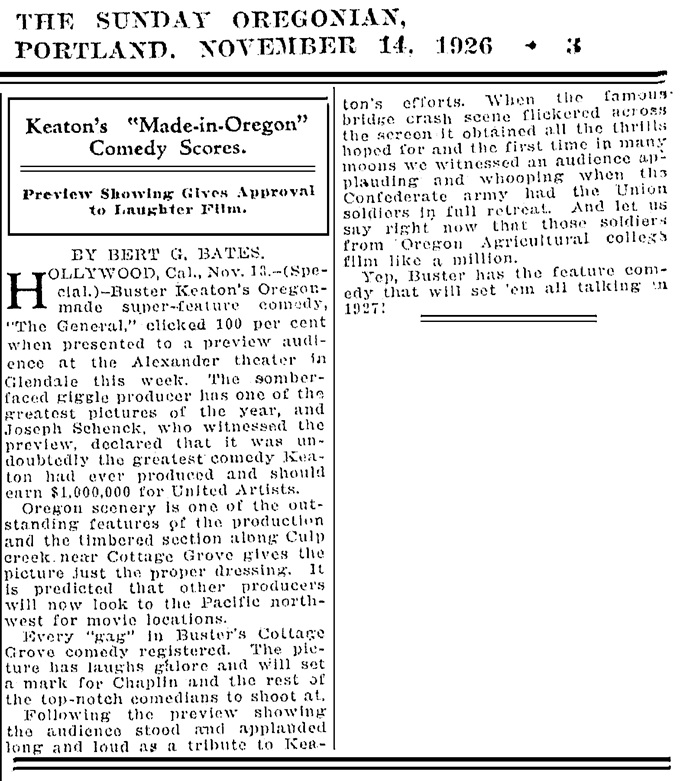

A few weeks later, on Friday, 12 November 1926,

The General was given a third test screening in Glendale, California.

By the time of the Glendale screening, the reel changes were set

and the film was mounted onto 8 reels (we have physical evidence of that).

According to Bertram G. Bates (2 May 1898 – 10 June 1963) in The Oregonian (14 November 1926),

“Buster Keaton’s Oregon-made super-feature comedy,

‘The General,’ clicked 100 per cent when presented to a preview audience

at the Alexander theater in Glendale this week.

The somber-faced giggle producer has one of the greatest pictures of the year,

and Joseph Schenck, who witnessed the preview,

declared that it was undoubtedly the greatest comedy Keaton has ever produced

and should earn $1,000,000 for United Artists....

The picture has laughs galore and will set a mark for Chaplin

and the rest of the

|

|

Ah. Look what I just found:

|

|

|

Again, pay attention to the ecstatic review and its report of the thunderous audience reaction,

the standing ovation and loud applause.

So much for the current belief that audiences of the time were indifferent to the movie.

|