A Message from Germany |

|

It was

probably in February 1960 when, of all possible fortunate coincidences, the best occurred.

Had KirchMedia contacted Buster just five years prior,

he would have said something to the effect of,

“Who the hell wants to see a picture that’s forty years old?” (Curtis, p. 611)

Had Raymond Rohauer not ensnared him,

Buster would have had to tell KirchMedia, “Sorry, I don’t have any of my films.”

Now that Rohauer had acted so quickly, and now that he and Buster had a contract,

and now that Rohauer had turned up so many films and ethically or otherwise laid claim to them,

Buster could tell the KirchMedia emissary that, yes, he had his films and he could work out a deal.

Perhaps he thought this was all a bunch of crazy talk,

but just a few months after that conversation, When Comedy Was King,

which included a condensation of his own film Cops,

was released and it was a

|

|

My suspicion is that the timing was not a coincidence.

Take a look at this passage from an

online article by Dick Bann:

|

|

The Buster Keaton revival may never have happened were it not for the role Hans Andresen played

in consolidating rights to Keaton’s silent films from three overlapping claimants,

then financing the preservation performed by Raymond Rohauer,

and touring with them both in Europe, before finally returning to America for rediscovery.

Keaton, incidentally, is yet another example of an iconic artist

who indifferently abandoned the nitrate of his own master works, believing them to be worthless!

Even near the end of his life during the 1960s,

Keaton could not fathom why audiences would care to watch films he made which were four decades old.

|

|

Ray Rohauer needed to amortize his investments, but the rights were all tied up.

He needed a third party to consolidate the rights so that he could exhibit the films commercially.

I bet it was Ray who called Hans and suggested that he talk with Buster about reissuing the movies.

If my guess is correct, then suddenly all the disparate pieces fit together perfectly.

Once Hans Andresen could consolidate the Friedman/Schenck rights, Ray would be free to show the movies anywhere.

|

|

Is not the above article odd?

Dubbing dialogue into his silent movies?

With the help of René Clair?

Could that have been the plan?

I thought not, but a little voice in the back of my head kept telling me to look at the Blesh book again.

Pages 352–353:

|

|

Keaton’s fine early work — the shorts and features made with his

own company and long since retired from projection — loomed as the

most feasible means of restoring the artist’s fame, stimulating new

opportunities, and bringing in needed income. Their comedy was

fresh; only sound would be needed, which could be dubbed in —

music, sound effects, and, here and there, actual speech. Although

Keaton had released all rights, some arrangement might be made.

During this period before the coming of television, Leo Morrison

and Buster Collier independently attempted to get these early masterpieces,

which dated from 1920 to 1928, released under some new

arrangement. Finally, Joe Schenck gave his substantially disinterested

consent, provided Keaton would finance the project. Once under way,

the bulk of the profits would then go, as in the past, to Schenck and,

presumably, the old stockholders, though this point was not clarified.

However, it was not entirely this far-from-equitable arrangement that

stymied the project but the unavailability on the one hand of cash

and on the other of films. For the shocking fact was uncovered that

the Keaton films had been destroyed, original negatives and all. They

had been put in storage in 1928 and 1939. During the

|

|

I had not read that passage since probably the 1970’s.

Looking at it again, I can somewhat piece it together.

The idea for sound effects and dialogue seemed to belong to Collier and Morrison,

and Buster probably went along because why not?

After all, when silents were reissued, they had sound effects and most had dialogue or narration.

We can see some examples, and here I need to thank the many contributors to NitrateVille

for pointing these out to the world:

|

“Paramount Screen Souvenirs” — click on the image to view This series began in 1931, and this clip is posted at https://filmlibrary.shermangrinberg.com/?s=file=418297. |

|

Some of Pete Smith’s “Goofy Movies” from 1933 and 1934

reprised silent shorts.

I have one or two somewhere in my storage locker.

I looked for an example online but came up empty.

What I did find was a different episode,

which did not concentrate on silent footage, alas,

but it should give you an idea of what Smith did to the silents:

|

Click on the image to view https://archive.org/details/ goofymoviesprogram11933_201912 NRA was not what you’re thinking; it was the National Recovery Administration. |

|

Pete Smith reprised his reprises in the early 1940’s with a

|

|

Gerald Santana, Flicker Flashbacks - Rare RKO/Pathé Newsreel & Silent Nickelodeon, posted on Sep 11, 2015 |

|

A bunch of Chaplin’s silent shorts were reissued by several companies.

Here is an example of the RKO/Van Beuren series, 1932 through 1934,

with sound effects but thank heaven without any talking:

|

|

And if you want to see something really wild,

here is what the Italians did in 1935 to their feature film of 11 years earlier:

|

|

Zo, I guess that was just the way things were done back then.

There seemed not to have been a thought about reissuing authentic editions commercially.

Even Chaplin fell under that spell when he reissued The Gold Rush in 1942,

a cropped and

|

|

When television infected our homes in the 1950’s, it continued in the grand tradition of humiliating silent movies.

We already delved into the world of Paul Killiam, who devoted

a goodly portion of his career as a

|

|

Buster, as we know, was a visualist who liked to tell his stories with as few words as possible.

Whatever he may have originally pondered, he ultimately decided that the sound would be music only,

no sound effects, no talking.

|

|

For five years?

That indicates that, probably moved by the George Eastman Award,

probably influenced by Sidney Sheldon,

probably convinced by MoMA and the Academy, he had begun to search out his lost movies as early as 1955,

when he made that trip to James Mason’s residence.

Why did he say, “We’ll keep all the subtitles”?

Because Chaplin had been excoriated in some quarters for deleting the titles

in The Gold Rush and replacing them with narration.

Buster wanted to make clear that he would do no such thing to his own movies.

An hour and 40 minutes? Either he misspoke or he was misquoted.

A more-correct ballpark figure would have been an hour and 20 minutes, of course.

Beyond that, and more importantly, it is heartening to hear him be so defensive about his movie,

which is an attitude he had not taken in earlier years.

|

|

(Some lines were scrambled below. I put them back into order and left obvious clues about where I made the repairs.)

|

|

So, what was all this about The General being shown at a campus movie house?

That was almost certainly in 1956, when Robert Smith, Sidney Sheldon, and Donald O’Connor

tested ideas for The Buster Keaton Story by showing a dozen of Buster’s movies

at various colleges and universities in Los Ángeles.

I wish I had details.

I am absolutely DESPERATE for details.

|

|

hermankatnip, Buster Keaton Interview 1960 Remastered Audio, posted on Dec 3, 2018. Interviewed by Studs Terkel. Also available on StudsTerkel.WFMT.com. Originally broadcast on 5 September 1960. When this video vanishes, download it. |

|

Sad to hear Buster struggling not to lose his breath while talking with Studs Terkel.

Chain smoking was doing him in.

Back in them thar days, pretty much all grownups were chain smokers.

From the 1920’s through the beginning of the 1970’s,

grownups almost without exception were chimneys.

Even at the tender age of seven, I began to feel embarrassed for all those grownups.

|

|

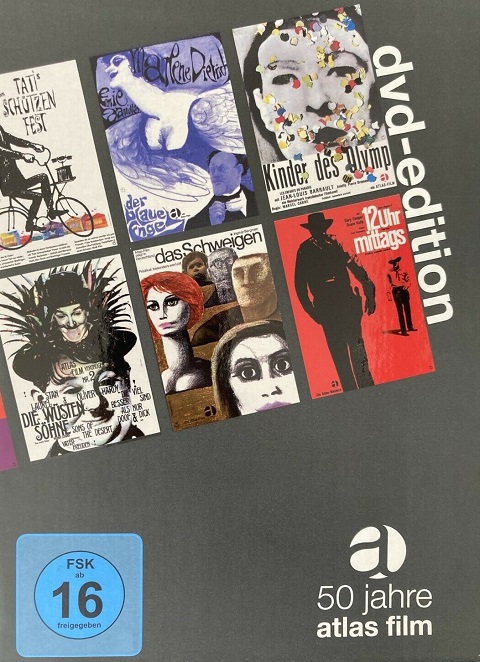

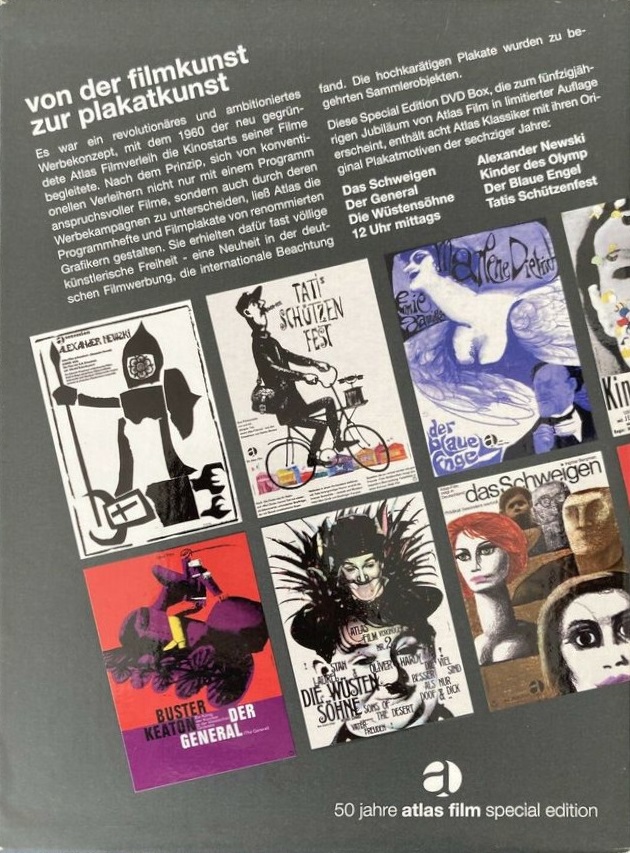

In the above interview, Buster explained that he was about to reissue his silent movies in Europe with orchestral tracks.

True. KirchMedia was behind this.

KirchMedia was founded by Hanns Eckelkamp and managed by Hans Andresen.

Together they also controlled Beta Film of Munich, Beta Film Technik of Munich,

and Atlas Filmverleih of Düsseldorf.

Alas, KirchMedia did not score or issue all the films, but only a few.

For the German releases, KirchMedia released through Atlas Filmverleih GmbH.

|

|

The General did not get its promised orchestral score.

Rather, I should say, it only got part of its promised orchestral score.

|

Entertainment Films Company, NYC |

|

It was probably in 1961 that this catalogue first included The General,

presumably copied from William K. Everson’s print,

and I presume Bill’s print was a copy of the MoMA print,

but I really don’t know and I really need to see this, but where on earth can I find a print?

|

|

Just discovered a capsule history in Samuel K. Rubin’s

Moving Pictures and Classic Images (Jefferson, NC: McFarland, 2004), p. 176:

|

|

ENTERTAINMENT FILMS

Entertainment Films made a splash in the early 1960s when it entered the 8mm

production market. One of the pioneers in the field, it made its debut with fanfare

and began producing 8mm silent titles which made the average collector drool.

Early on, the company produced quality prints of

The Mark of Zorro and

The General. Then, in the years to follow, it offered such attractive items as

The Iron Mask,

Thundering Hoofs,

The Leatherneck,

Son of the Sheik,

Way Down East,

The Cat and the Canary,

The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari,

10 Days That Shook the World,

Metropolis,

Merry-Go-Round,

The Yankee Clipper,

Raffles,

Road to Yesterday,

Eyes of Youth and

Hell’s Hinges.

I have no way of knowing what actually happened, but deliveries from the

company began to take longer and longer. There were quality complaints, most of

which I understand were resolved. Then, a series of broken promises about deliveries

followed

My feelings are that the company over-extended itself and fell by the wayside

because of it. Phil Alcuri, who headed Entertainment, attended several Cinecons

and was extremely cooperative with collectors in the early stages of its existence.

Too bad! They had a good thing going!

|

|

I assume that it was Entertainment Films Company of New York to which Mr. Rubin referred in the following 1968 AP story.

(Again, I descrambled a line and left an obvious clue.)

|

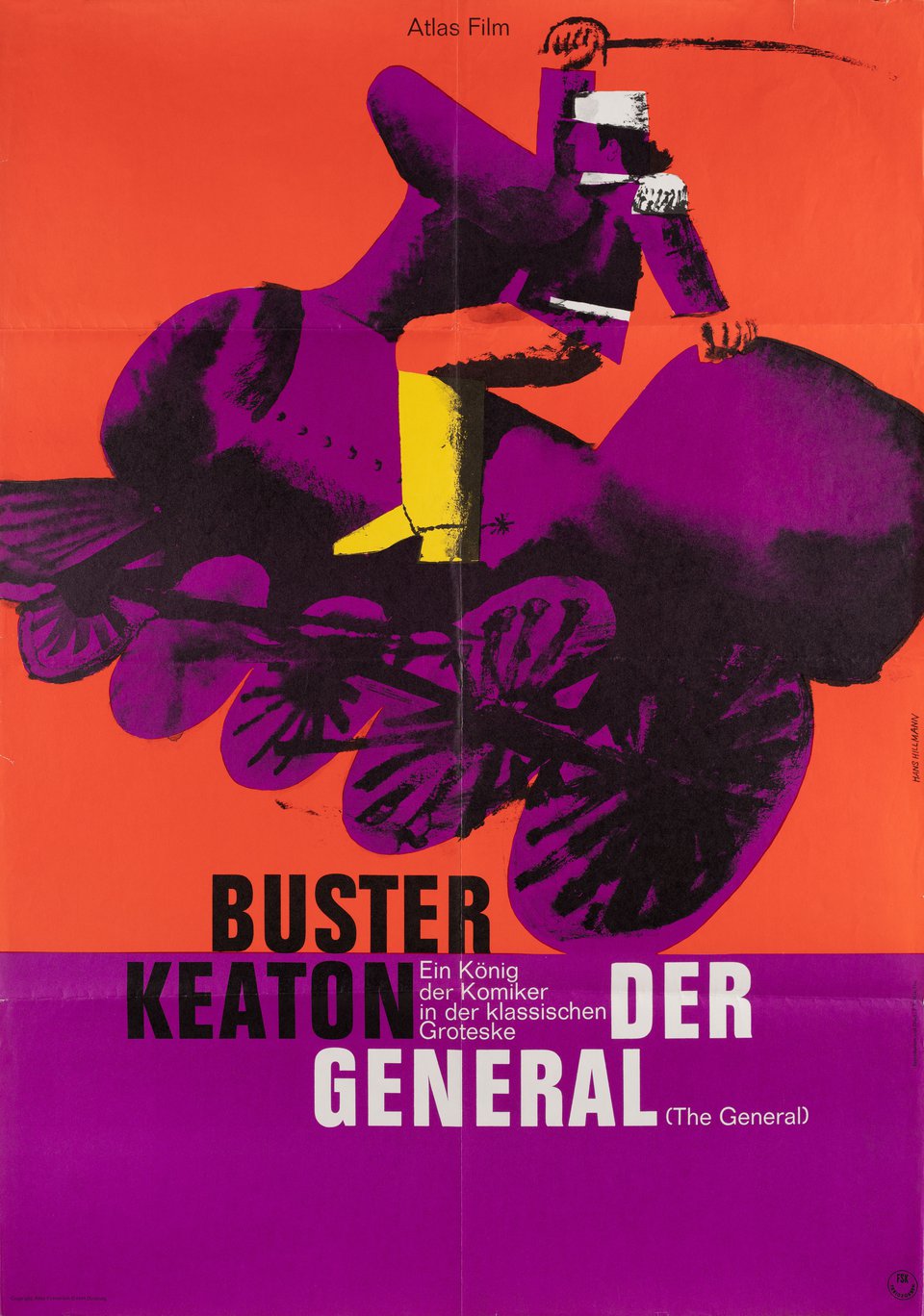

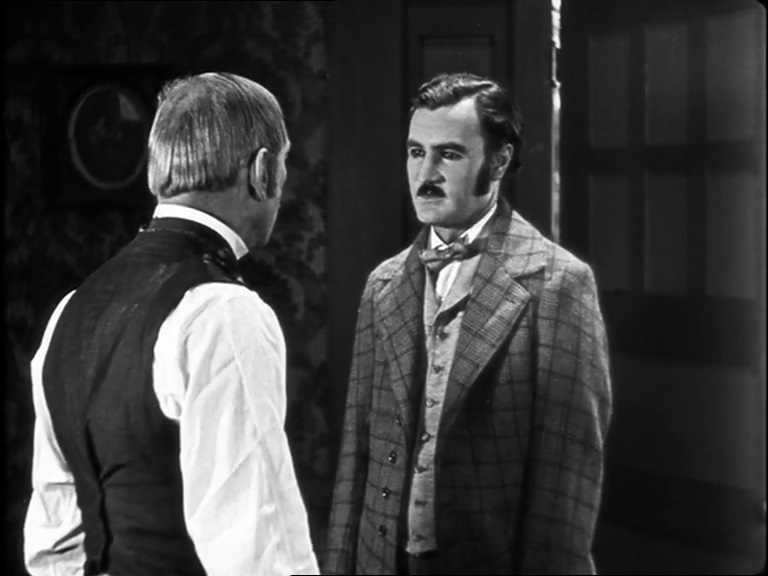

An Atlas Film release, 1962. German poster designed by Hans Hillmann. Click here for the brochure given out at the German roadshow screenings. See also this. |

|

Atlas Filmverleih GmbH (Graf-Adolf-Straße 22, Düsseldorf)

would not make the mistake that United Artists and Joe Schenck had made in 1926 and 1927.

The distributor would not merely dump the film into some cinemas and hope for the best.

The Atlas publicists would make certain that this was a major event with major news coverage.

|

|

How?

In his book, Es Darf Gelacht Werden von Männern Ohne Nerven und Vätern der Klamotte,

Norbert Aping reveals the secret formula.

|

|

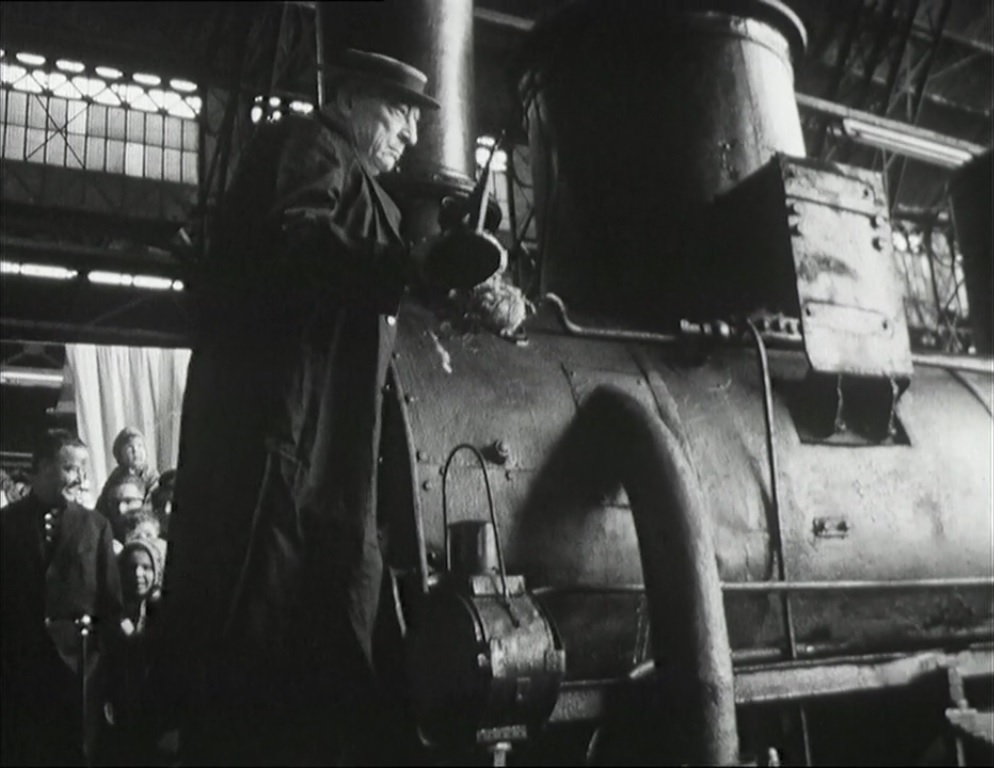

[Werner] Schwier had taken [Buster] on a locomotive ride through Germany for Atlas Filmverleih

to promote Keaton’s feature-length silent film classic, The General, 1927).

This was shown again for weeks in

|

|

Hanns Eckelkamp, born 27 February 1927, Münster; died 5 August 2021, Berlin.

|

|

Buster appeared on Season 1, Episode 28, of Werner Schwier’s TV show, “Es Darf Gelacht Werden,”

Tuesday, 6 February 1962, and I would love to get a copy.

Here is an article about that:

James Halbe, “Buster Keaton Brings Laughs to Germany,”

Stars and Stripes, 6 February 1962:

|

|

Buster Keaton, famed silent-film comedian, poses with a television camera at the Hesse State Radio studios in Frankfurt in February, 1962. (Norm Zeisloft/Stars and Stripes)

FRANKFURT — Buster Keaton, the man with the saddest deadpan face in show business and one of its all-time comic greats,

arrived in Frankfurt Monday to show Germans why America laughed at him 40 years ago.

For 67-year-old Keaton, it is a triumphal return.

He was a little-known vaudeville actor when he sloshed through the mud near Amiens, France,

in 1918 as a corporal in the 159th Infantry, 40th Div.

This time, he will chug into 13 German cities in a 100-year-old locomotive

to kick off a revival of the silent films which made him famous in the 1920s.

With the same gifted flair for comic pantomime as he had in 1922,

he breezed through an unrehearsed television show at he Hesse State Radio here Monday,

then sat down with 30 reporters and photographers and told them why there aren’t any more comics like him today.

“The nearest thing we have today to what Charlie Chaplin, Harold Lloyd and I were in the old days,” he said,

“is Red Skelton. He could have been a star in the silent days. And there’s Jackie Gleason, too, and the late Lou Costello.

“And Ernie Kovacs was getting mighty close to it if he’d just been let alone.

But there aren’t any real natural comics any more.

There are a lot of gag men, like Bob Hope and Jack Benny.

But they depend on their gag writers. They’d be lost without them.”

Keaton was rehearsing a television show with Ernie Kovacs until 7 o’clock

on the night Kovacs was killed last month.

Kovacs was driving home on the Los Angeles Freeway when his car struck a tree, killing him instantly.

“In the old days,” he said, “we worked entirely without a script.

I never made a picture with a script.

And most of the time I was my own director.

We’d have a story idea. And we’d run through it.

We would shoot the first part, then the last part,and then weave the story through the middle.

“I never worried about the middle.

It always took care of itself.

As long as we had a good story with a good beginning and a hood ending, we never worried.”

Most of his film comedies in the 1920s cost less than $250,000 to produce, he said.

“We had a whole studio staff on the payroll 52 weeks a year,” he said.

“We made seven or eight ‘shorts’ or about two features a year.

If we didn’t like the sequence,

we could shoot the whole thing over again for just the cost of the film.

A day’s shooting cost us maybe $8.50 for film.

Today, the minimum cost for reshooting a scene is $12,000.

You don’t have any freedom when you’ve got to pay out that kind of money.”

Keaton and his wife leave Tuesday for Munich. The rest of their schedule:

Ulm, Feb. 7;

Stuttgart, Feb. 8;

Mannheim, Feb. 9;

Frankfurt, Feb. 11;

Cologne, Feb. 12;

Duesseldorf, Feb. 13;

Bremen, Feb. 14;

Hamburg, Feb. 15;

Hannover, Feb. 16;

Berlin, Feb. 19; and

Nuernberg, Feb. 19.

French film officials will hold a reception for him in Paris Feb. 22 at the Cinematique Francaise

to mark the opening of a run of all of his 38 films, one each day.

The Keatons will sail for America on the liner France Feb. 23.

|

|

Below we have a nearly illegible article that contains good info not found elsewhere.

I retyped the main text in a similar font with almost identical spacing,

and I replaced whatever images I could.

Two of the images from The General, by the way, are not unit stills but frame

|

|

Atlas was founded in 1958 and was defunct by 1966.

Well, that’s what I thought I read somewhere,

and I’m kicking myself for not including a link, which is why I cannot check my work.

Oh. here it is.

It turns out that Atlas Film is still very much alive and active

and its website details its

history,

which stretches back to 1946,

when 19-year-old Hanns Eckelkamp established a cinema.

Atlas went into film distribution in 1960, and, yes, it closed in 1966, but not permanently.

|

|

By some supernatural miracle of some gods or nixies or pixies or something,

Rohauer and/or KirchMedia were able to locate several original prints of The General.

Or so the story was told, and so Buster believed.

In fact, the KirchMedia edition was sourced from Rohauer’s dupe neg of the 12 November 1926 preview print.

I do not know, but I would suppose that Rohauer learned the art of ballyhoo from Herr Schwier,

perhaps not directly, but just by observing.

Rohauer was in Munich for the première.

Atlas would distribute the movie throughout West Germany (and Austria and Switzerland maybe???)

initially as a roadshow presentation.

|

|

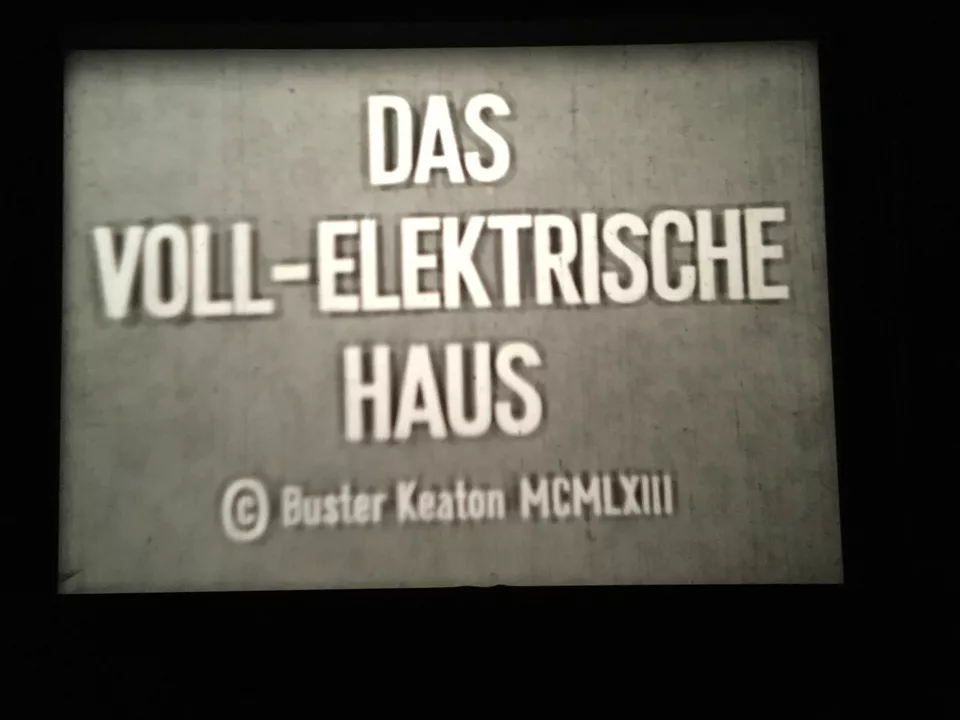

Buster oversaw the creation of the score, which was played by a small orchestra.

He approved it, but, unfortunately, nobody has ever heard it.

KirchMedia replaced that score with a new soundtrack by

Konrad Elfers, who composed a Dixieland-type of jazz for music and added cartoon sound effects.

Why? I don’t know.

Perhaps KirchMedia simply didn’t like the orchestral score?

Perhaps someone erased the master tapes by mistake?

Perhaps a legal problem developed with the composer or orchestra?

Perhaps Konrad Elfers had his lawyer approach the KirchMedia executives, waving a contract that was being breached?

I don’t know.

This new soundtrack was surely under sole license to KirchMedia.

|

|

Oddly, Diario de Cine claims:

“Sound version, produced and directed by Buster Keaton in 1961 with music by Konrad Elfers....”

No. Something got mixed up.

|

|

Oh no. No. No no. Wait. Wait wait wait. It just now occurs to me.

The mix up.

That’s the clue.

The mix up is the clue.

I know who composed and conducted the

|

|

Here’s another conjecture, and this one I’m less confident about.

KirchMedia surely did not wish to alienate or anger Buster, because to do so would have jeopardized its business plans.

So, what probably happened is that the KirchMedia execs told Buster that they would preview the film twice,

once with the Buster-preferred accompaniment and once with the KirchMedia-preferred accompaniment.

When the KirchMedia-preferred accompaniment got more laughs, Buster surrendered.

I do not know this.

This is just my imagination.

It is only my imagination.

Purest fantasy.

Again, it’s exploratory conjecture.

My imagination fits the known facts, but that’s the only defense I can provide, and it’s a weak defense.

Nonetheless, until better info turns up, I’ll stick with my fantasy as the most likely story.

|

|

So, what is he saying above?

He “sneaked into the theatre”?

Why didn’t he say that he “snuck into the theatre”?

Did he misspeak?

No, he did not misspeak.

I am certain that Don Alpert or his editor at The Los Ángeles Times mangled Buster’s words.

I am certain that Buster actually said that “I sneaked it in a theater.”

As I mentioned above, I am nearly certain that the film was sneaked not once, but twice,

whether in the same cinema or in two different cinemas, I do not know.

One time, the print had the original Elfers music track that Buster had approved;

the other time, the print had the revised Elfers music/effects soundtrack.

Though Buster did not say so explicitly, it is clear that he was present during the sneak previews

and that he heard that the laughter was the same as it had been in 1926/1927.

Whether or not the audience knew he was there is anybody’s guess.

We absolutely MUST find that unique print with the original Elfers score, sneaked once and never seen again.

When the Atlas licenses expired, all its materials were returned to KirchMedia,

which seems no longer to have any of it.

If you are in the archiving world, you have more pull than I do.

Please please please please please ask around.

If the print no longer exists, maybe the audio negative is still on file somewhere.

If the audio negative no longer exists, maybe the tapes are still on file somewhere.

If the tapes no longer exist, maybe the score is on file somewhere.

If the score no longer exists, maybe the parts are on file somewhere.

If these materials are not in the KirchMedia collection, perhaps they are in the Elfers collection.

If there is no archival Elfers collection, perhaps the Elfers descendants still maintain some of his belongings.

(Konrad Elfers, 25 Oct 1919 – 22 Sep 1996, which was not that long ago.)

Please dig into this.

The world would owe you bigtime.

|

|

Odd that Buster was shocked by A Shot in the Dark,

since he had done about as much in The Cameraman.

Maybe someday it will dawn on me what so offended him about the Sellers flick.

(I liked Tom Jones when I first saw it. I disliked it when I second saw it.

It was a beautiful book but a rotten movie.

I don’t understand why it was a hit.)

|

|

There has been so much confusion about the 1962 German version.

We Americans vaguely know about a sound version of the film that played in Germany,

and we assume that it must have been the same Jay Ward Productions “sound version” that was released here.

It was not.

Those were two entirely different works.

Europeans, as far as I am aware, have never seen or even known about the American “sound version.”

Probably a few thousand of us saw the American “sound version” decades ago,

but our memories about it are pretty dim after half a century,

and so we Americans can’t remember the copyright date that we saw in tiny print during the opening credits.

It could have been 1953, it could have been 1977, it could have been 1962; we just don’t know,

and so we all just assume that the version that toured Germany in 1962 was the same as the American “sound version.”

I made this same mistake in an earlier draft of this web page.

There was no relation. No relation at all. They were two entirely different versions.

I strongly doubt that the Jay Ward Productions crew were even aware of the 1962 German version.

|

|

Probably the first time the KirchMedia/Elfers edition of the movie

was seen and heard on these shores was on the evening of Thursday, 10 November 2022,

in my tiny apartment, with my cat and myself as the sole audience as we watched it on a British VHS.

|

|

There was a problem with reissuing an older film in the 1960’s:

Almost no commercial cinema was set up to present it properly.

In the late 1950’s and early 1960’s, managers confiscated the older lenses

and instructed their projectionists to run everything in widescreen.

When newer cinemas were built, only widescreen was installed.

If older films were run, the top and bottom of the image would be lopped off, and not just a little bit.

The result was ruinous.

In the US there was only a handful of cinemas that could still present the Academy format (.600"×.825"):

a few in LÁ, a few in NYC, and maybe one in Chicago,

and that was probably it.

As for the formats that predated Academy, forget it.

No commercial cinema anywhere could accommodate.

Did the same hold true for Europe in the early 1960’s?

I don’t know, but film scholar/accompanist Andy Benz assures me

that German cinemas in the 1960’s were still commonly presenting the Academy format properly.

|

|

Were there European cinemas in the first half of the 1960’s that were incapable of presenting Academy

but that instead cropped the living daylights out of taller movies?

I suppose so, but I don’t know.

Anyway, it hardly mattered, as we shall discover.

|

|

According to Rudi Blesh’s book, Keaton (NY: Macmillan, 1966), p. 369:

“Rohauer got The General, with added soundtrack, exhibited in central Europe,

with Buster himself piloting a replica of the old locomotive... from Germany to Austria.”

When I read this book multiple times at age 15, I puzzled over that sentence.

I could not make sense of it, no matter how many times I read it over.

Were I to have read that book for the first time decades later,

I would still have puzzled over that sentence.

I need puzzle over it no longer.

We shall shortly all bear witness to the meaning of that sentence.

Also, note that Blesh credited Rohauer for getting the movie shown in Germany.

It was Hans Andresen’s pet project, to which Hanns Eckelkamp gave his blessings,

and for which Werner Schwier invented an ingenious publicity campaign.

Rohauer had nothing to do with any of that.

He was there for the ride, by Buster’s side as 50/50 business partner,

and he supplied the dupe negative to KirchMedia.

That he would later take sole credit for everything is beyond outrageous.

Anyway, that one little sentence, penned by Blesh, which I read at age 15,

derailed my research for the next four and a half decades.

It was an innocent, understandable mistake, but it had me barking up all the wrong trees.

Now we have online newspaper archives, which are a gift to researchers,

and we also have scholars from around the globe participating in online chat groups,

and so now, at long last, I can get some idea of what actually transpired.

|

|

The 1962 preview is on YouTube. Behold:

|

|

https://youtu.be/HwMf3w0RA6o When YouTube disappears this, download it. Just discovered that it’s also on Daily Motion. Note how the forest in the background becomes blank white and a bit flickery. That’s because this preview is a dupe of a dupe of a dupe. |

|

Now that we’ve reached this moment of the story, let’s perform an experiment.

Here is a frame from the Atlas preview, as it appears on YouTube,

alongside the same frame as it appears on the Kino Ultimate Edition:

|

|

|

|

Confession: The YouTube video is a bit distorted and it is tilted a bit, and so I rotated it slightly.

Now, let’s see what happens when we plop the YouTube screen grab on top of the Kino Ultimate Edition screen grab:

|

|

|

My conclusion: Something is seriously wrong.

What?

Coupla possumbilities:

• We need to remember that the silent image is considerably larger than the sound image.

Could it have been that the lab optically reduced the size of the image to fit onto a sound film?

Could be. Could be. Could be.

But if so, then why is so much of the image lopped off on all four sides?

Well, we need also to remember that most film-to-video transfers lop off all four sides as a matter of course.

Why? The answer to that question is obvious: The techies want it that way.

Why? Cuz.

Is that really what happened here?

At first, I thought so.

Then I began to think not.

• Did the lab perhaps decide not to reduce the size of the image to fit onto sound film,

but, rather, to crop it to fit?

If that is the case, then we need to remember that the soundtrack is on the left side.

Usually when silent films are cropped to conform to sound film, it is only the left side that the lab lops off.

Here, though, both the left and the right are lopped, pretty much equally.

Could it be that the lab decided not to lose 10% of the left of the image,

but instead to lose 5% of the left and 5% of the right?

That would require some realignment, but such a strategy would be consistent with what we see here.

The cinemas, and, of course, the film-to-video lab, would complete the job by lopping off the top and bottom.

That might be what we’re seeing here.

I really don’t know.

• Later I got a VHS and then a DVD edition of the 16mm edition shown in the UK.

It confused me mightily.

More than 56% of the image was missing, on all four sides.

Did that 16mm edition reflect the state of the 35mm edition?

• I purchased a 16mm print of the German edition, and, just like the videos,

somewhat more than 56% of the image was missing, as we shall witness below.

Unable to endure the mystery any longer, I asked the friendly folks at the DFF Deutsches Filminstitut & Filmmuseum

if they could send me an image of a few frames.

They kindly did so, gratis.

As a matter of fact, they sent me several different attempts.

When the images arrived in my email, I screeched in horror.

My cat got worried about me and so she dashed over.

I showed her the computer screen and she screeched in horror, too.

Oh, I suppose you don’t see a problem.

The problem screamed out at me instantly.

This looks like the Academy format, with large, thick black bars separating the frames.

So, looking at this casually, anybody would assume that this is an optical reduction

that retains the entire silent image, just smaller.

That is not what this is at all.

Shall I explain?

Let us compare the above image with the same frame on the Kino K669

Let us compare that to the Lobster DVD:

As you can see, the rounded corners so visible on the Lobster edition

do not derive from the rounded corners on the film frames.

Lobster interpolated them digitally.

But, of course, I’m wrong! Again!

What we think we see ain’t what we see at all, folks.

The thick black bar separating the frames was a defect that appeared on this particular frame,

the result of damage of some sort.

When we back up a bit, we discover that the problem is much simpler:

The left side was lopped off all the way through.

See? The other frames have thin black lines separating them,

just like silent films and early talkies.

Notice something else: There is a second translucent frameline right below the black frameline.

Why?

Somebody at Beta Technik goofed and at one time misaligned the film on a step printer, resulting in that defect.

Why didn’t Quality Control catch that?

Apparently there was no Quality Control.

Why was the preview formatted differently from the way the feature was formatted?

Because the crew that made the preview knew something about silent movies.

The crew that made the release prints knew NOTHING about silent movies

and had NO IDEA AT ALL what they were doing.

They treated a silent film as though it were a contemporary talkie that was designed for widescreen cropping.

|

|

My oh my oh my. Der General is scheduled for a film festival in Saarbrücken on Sunday, 18 September 2022

(coincidentally the same day that a Rohauer Collection DCP of The General

is scheduled at the American Legion Post 43 in Hollywood).

I suppose that there is a misprint in the German catalogue,

but it would be most interesting if that’s not a misprint after all,

and if this is indeed the edition that contains Konrad Elfers’s score:

|

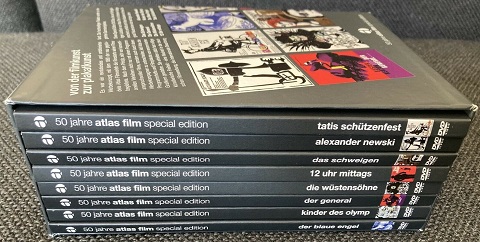

For half a minute, I thought that this 1962 Elfers version had been released on DVD. Nope!

Take a look at what a customer named

Casimir wrote:

Wasted Opportunities

Reviewed in Germany on 10 May 2013

Of course I bought the Atlas anniversary because of the slipcase,

for I wanted the silent film “The General” with Konrad Elfers’s famous music.

I still remember this composition, which was arranged in the style of early jazz, quite well.

At the beginning of the 1960’s, the director/star Buster Keaton

was traveling in Germany in proper style on an old locomotive

with exactly this version in his luggage to promote what is probably his most successful film.

Since the individual DVD covers were based on the poster designs of the 1960’s,

I naturally assumed that the versions of the films provided by Atlas would also have been used.

My disappointment was all the greater

when I finally found out that in the case of “The General” two relatively recent compositions were chosen instead:

Joe Hisaishi’s from 2004 and a version by Robert Israel from 1995.

Although both film scores are available in flawless 5.1 surround sound,

they don’t reach the rousing quality of Elfers’s Dixieland score, which at the time was recorded only in mono.

This hurts all the more since Buster Keaton’s legendary silent film classic

has already been released several times with music by Hisaishi and Israel.

A release of the Atlas Film version with its music on DVD and

I purchased this box set in the hopes of finding clues, and I found them!

This box set was issued in 2010 by Atlas Film!

The website is https://atlas-film.de/,

and that gives me some ideas.

I think I need to drop those folks a line.

And so I dropped them a line.

And I heard back. Quickly.

Atlas no longer has any materials at all on The General.

Nada. Nil. Zilch.

I attempted to watch The General on the second disc of this box set,

and why am I not surprised to discover that it’s not there?

The supplemental materials are all there, but the movie itself is nowhere on the disc.

|

|

Great info, but I have my doubts that Rohauer had ANYTHING to do with this campaign strategy.

If Sarris Overbosch approached anybody about the GKB 680, he most likely approached Werner Schwier.

Buster throttled the GKB 680 to seven cities at the early part of the tour.

A friend just found that the Internet has some footage of two of these events.

Click the images to watch the movies:

|

Munich, 5 February 1962 |

Bremen, 14 February 1962 |

|

Oh, I was wrong again.

The Internet has some footage of THREE of these events:

|

Hamburg, 15 February 1962 |

|

Oh, I was wrong again.

The Internet has even more footage:

|

|

|

This German revival of The General was a triumphant success,

and it spread out to France and elsewhere in Europe.

As Buster would remark a year later, “Right now, it’s playing all over Europe,

and people are laughing harder at it today than they did in 1927 when it came out”

(“Happy Pro,”

The New Yorker vol. 39 no. 10, 27 April 1963, pp. 36–37;

the printed interview is anonymous,

but the online edition credits Gardner Botsford and Brendan Gill as the authors,

and gives the submission date as 19 April 1963).

|

|

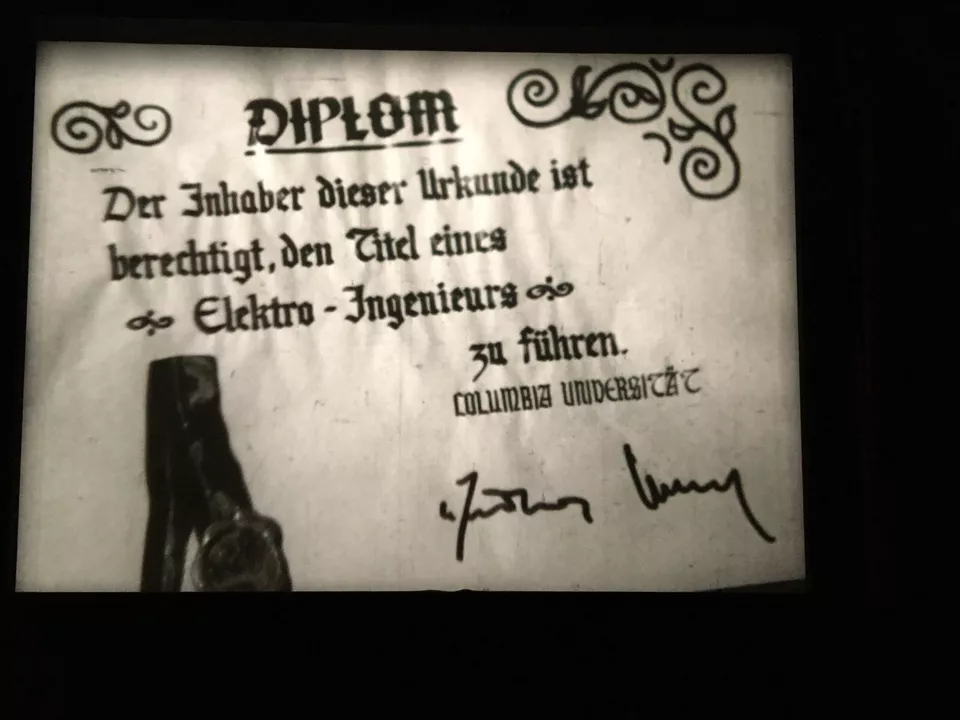

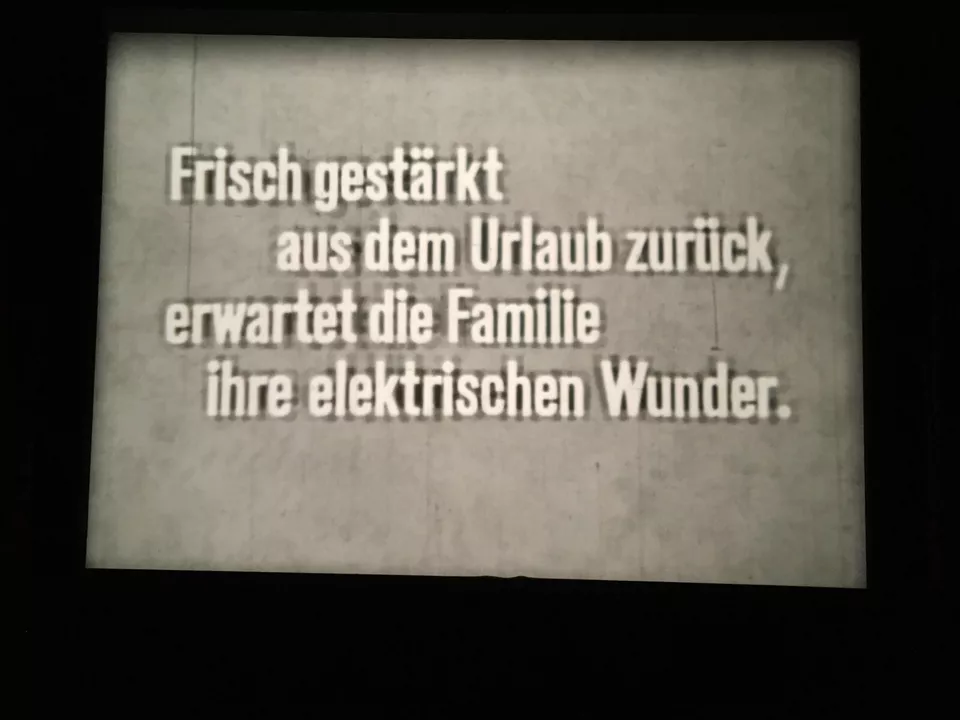

KirchMedia/Beta/Atlas prepared Cops and The General were prepared, yes,

but not only those.

Not long afterwards, they also prepared College

(Der Musterschüler) stapled together with

The Goat/Der Sündenbock and The Paleface/Das Bleichgesicht, also in 1962.

|

|

Now I find a 1962 Atlas poster for Go West

(Der Cowboy, together with The Balloonatic/Ballonschiffer).

|

|

I see a link to the 1964 Atlas poster for Battling Butler

(Der Killer von Alabama stapled to One Week/Flitterwochen im Fertighaus) as well.

|

|

I see the occasional Atlas poster for those latter two features, minus shorts, shipped out as a double bill,

but with a title changed:

Der Boxer.

|

|

I thought that was it.

Nope.

I just found this on eBay and placed a bid but lost.

|

Released in 1963, but where? What feature did it accompany? Was there another short on the program? |

|

Before the other Buster movies could be issued, Atlas shut down for a few years in response to financial difficulties.

I know no details.

Yet I see some of these Atlas editions reissued under the name of what appears to be a subsidiary,

Monopol-Films-A-G-Zurich. See

this and

this and

this and

this and

this and

this, for instance.

Did that happen while Atlas was hibernating?

|

|

With the February 1962 German reissue of Der General,

Buster revolutionized the business (without meaning to).

|