|

Anthony Slide, Nitrate Won’t Wait: A History of Film Preservation in the United States

(Jefferson, NC: McFarland, 1992), p. 51:

Film collectors can, and do, benefit archives, but there was also a time

when at least one archives, unknowingly, benefitted collectors. In 1956, three

major New York film collectors, whose names must remain anonymous, contacted

one of the vault custodians at the Museum of Modern Art. The Museum

employee was a gambling addict, and agreed to accept what the collectors

laughingly called a “stud fee” of $200 for each negative he would remove from

the Museum’s vaults and loan to the collectors for printing. A collector involved

in a peripheral way recalls, “It was a very modest thing, really no harm was

done. They were only getting a few things, like a Fairbanks feature, a Harold

Lloyd short, nothing big — only little things which they were interested in personally.

It blew apart when, like a lot of these things, they got greedy. And

they began to bring the stuff out like it was Ali Baba and the Forty Thieves.

Open Sesame and grab all the jewels. I don’t know the details of how this fell

apart, but it did in the end. The guy was not caught, but finally it got to the

point it got dangerous.”

|

|

|

Paul Killiam’s “Sound Version”

|

|

For half a century, I have been banging my head against the wall trying

to figure out how Paul Killiam acquired a copy of The General.

It was in

1957, surely in response to The Buster Keaton Story,

that Paul managed that feat.

I have no proof at all, but I have eyes, I have the Landmark Laservision/Republic laserdisc,

and I have a computer on which I can watch the file repeatedly.

Did Paul borrow a 35mm print from MoMA?

Paul convinced someone at MoMA to run off a new copy negative from the lavender, right?

Oh I was singing praises to myself, so proud that I had worked out a mystery that nobody else had ever worked out,

a mystery that nobody else even knew was a mystery.

I was floating on the clouds, so haughty about my genius instincts.

And I was wrong.

Totally, totally, totally, totally, totally wrong WRONG WRONG WRONG WRONG.

And wrong again.

That is not what happened at all.

|

|

Paul may have copied other stuff from MoMA (I’m pretty sure he copied lots from MoMA),

but he did NOT copy The General from MoMA.

Absolutely impossible.

So where DID he copy it from?

|

|

Somehow he found someone at MGM to make a copy negative from the

|

|

How would anybody in 1957 have known about MGM’s

|

|

Could Paul have somehow gotten the

|

|

It was not until July 1970 that anybody would have been able to notice

that Paul’s edition had a gap, a gap that exactly matched the damage

that the domestic camera negative had sustained by 1948.

But we don’t know that yet.

Nobody on the planet knew that yet — nobody except for Paul.

He had to hide that evidence, else he’d be found out.

We’ll get to that by and by.

|

|

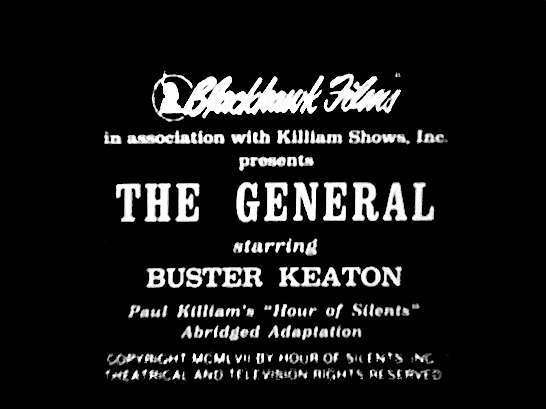

Once Paul had a complete copy negative in hand,

he ran off a positive cutting copy and then set about abridging it.

He did more, besides.

He deleted all the opening and closing credits and replaced them with new Killiam credits,

and so any clues that those original credits would have provided are gone.

After his editor chopped half an hour out of the movie, he added sound.

This would be for a proposed TV series, you see.

|

|

The series was to be called

“Hour of Silents,”

a

|

|

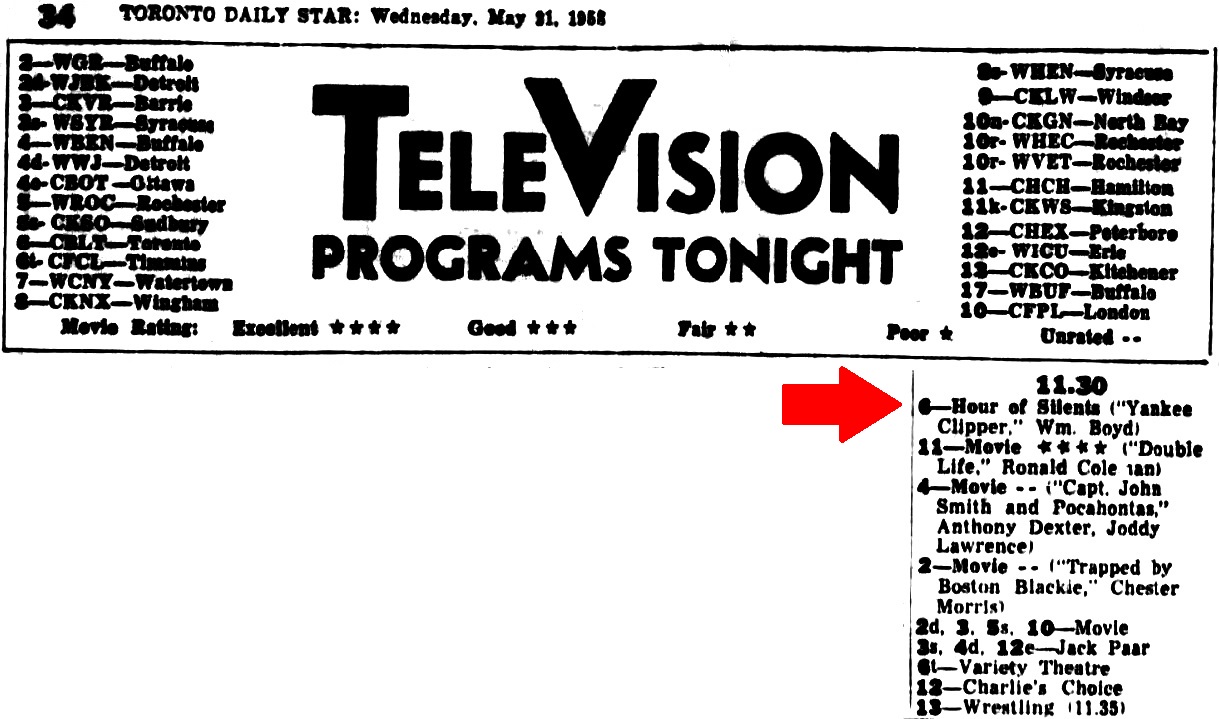

And Canada, too! The CBC (Canadian Broadcasting Corporation) picked up the series, but only briefly.

Well knock me over with a feather.

|

And that’s all I can find. Three episodes. Maybe there were more. If you can spot them, please let me know. Thanks! |

|

I just found a screen grab of the “Hour of Silents” edition on eBay,

and it predictably bears a 1957 copyright claim,

though I cannot find a registration anywhere:

|

|

|

Now we should look at this:

|

|

Notice something? A clue? A giveaway?

Look at the showtimes.

This “sound version” of The General began at 10:15pm and concluded at 11:05pm.

Fifty minutes.

Nearly a year later, another silent feature was shown on the BBC, The Yankee Clipper on

Sunday, 14 June 1959, originally

88 minutes but, predictably, it had a 50-minute time slot.

This broadcast was repeated on

Sunday, 13 September 1959.

Prior to this, in

1957, the BBC had broadcast Killiam’s

“Movie Museum” series.

All right, this is not fulsome research, but it is sufficient

to establish that the BBC had contracted with Killiam Shows for programming,

and that the BBC ran at least two episodes of “Hour of Silents.”

My guess is that when Paul failed to get his series broadcast,

he began selling it off one episode at a time to anyone he could,

in order to get at least some little return on his investment.

Paul did manage to sell his episodes to individual stations in the US.

Witness one recollection by a

George who seemed to be speaking of his youth in Texas:

“Plenty of titles followed by the early 1960s on TV,

including a series called Hour of Silents, which showed

|

|

We see here that Paul Killiam’s “Hour of Silents” version of The General

was also shown on WVIA Public Television Channel 44 in Scranton, Pennsylvania,

on Saturday, 26 October 1974.

How do we know that this is the “Hour of Silents” edition?

Because the article pulls quotes from Paul’s old press release,

which invented turns of phrase that by the 1970’s were being repeated everywhere

beyond the point of cliché.

|

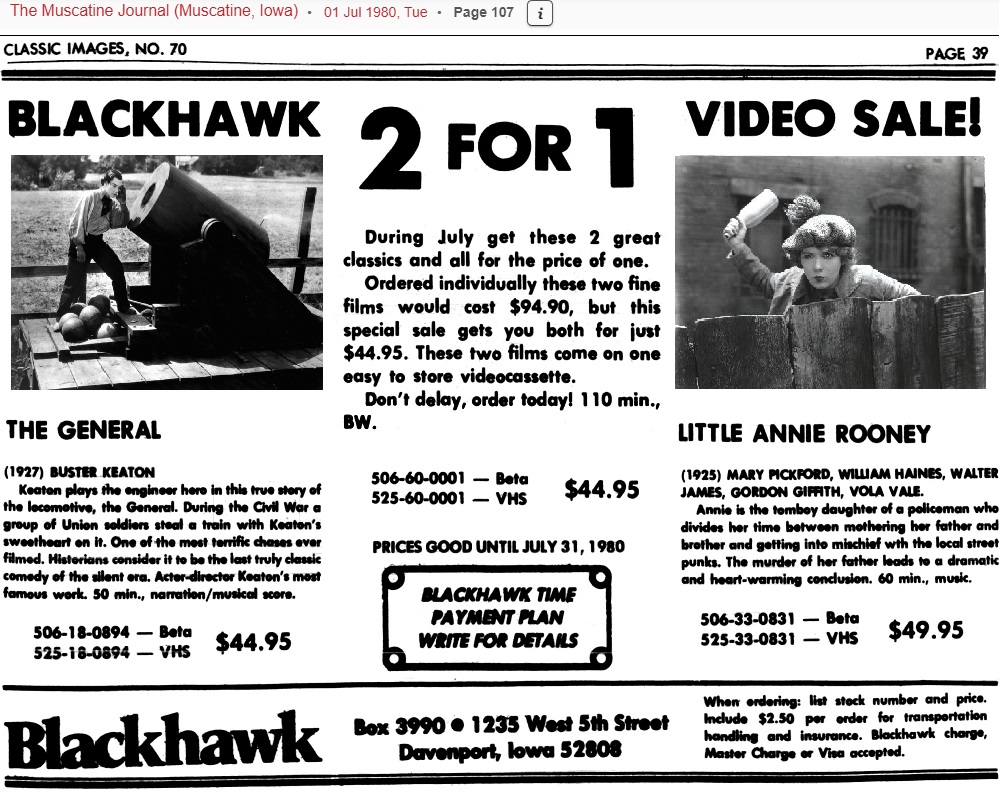

This was the first I ever heard about the “Hour of Silents” edition of The General having once been offered on home video. See also page 12. |

|

|

Paul Killiam’s narration is a disgrace.

The

The rest of the cues?

Prior to the days of the WorldWideWeb, investigating this would have taken decades rather than just two days.

The Retro 1950’s album was published by the successors to

Thomas J. Valentino, Inc.,

Production Music Library.

Now we’re getting somewhere.

When we Google “Playtime” and “Valentino” and “Music Library,”

we land on

this spreadsheet,

and there we discover, on page 133, that the composer was

Ernie Watson.

We need to crosscheck our work.

We go to YouTube and plug in “Ernie Watson” and “Playtime” and we hit the

• stroll (00:15)

• enlist (02:14) • rejected (06:12) • Kingston (11:04) • cannon (11:56) • flames (42:15) • rush (42:20) • flag (the beginning is traditional, but I can’t place it, 46:23)

That’s eight cues Shazam can’t identify.

No matter how many times I ask, Shazam just sheepishly shrugs its shoulders.

AHA Music isn’t helping either.

SoundHound is equally baffled.

The cannon thingamaroo sounds so similar to some pieces by

Roger Roger,

but I have no luck in locating it.

The bit at 46:23 with Johnnie filling in for the standard-bearer is from a symphony of some sort,

but we hear only a few notes before it crossfades to a musical effect, and musical effects, being only two or three seconds long, are almost impossible to identify.

So, I Googled to see who else could help, and Google said Google.

Google informs me that the call for volunteers

(03:09) and

Johnnie alerting the troops back in Marietta (40:07) are

Gustav Holst, “The Planets, Opus 32, Jupiter, the Bringer of Jollity” (1918).

That makes me feel superdumb.

I knew that music, but my mind had totally blanked and made the piece utterly unfamiliar.

Google also informs me that the scene of the Raid (08:16)

is Tchaikovsky’s “Francesca da Rimini,

Opus 32, Orchestral Fantasia after Dante” (1876).

Yup. Bingo.

Which particular recordings of these two pieces, heaven only knows.

The particular renditions of “Oh, Susanna,”

“Dixie,” and “Battle Hymn” are probably also from Valentino, but those will be harder to trace.

This was the wrong way to present The General,

the wrong way to edit it, the wrong way to create a soundtrack, the wrong way to choose a musical accompaniment.

This version of the movie is dead, flat, dull, dreary, repulsive.

I have no evidence, but I am certain that this edition drove thousands of potential admirers away forever.

Everything on screen was created by Buster, yes,

but it has all been so mangled, so ruined, so corrupted, that the result cannot be considered his by any argument.

This “Hour of Silents” edition of The General is a powerful demonstration

of a distributor’s poor editorial choices wrecking a film

and destroying a filmmaker’s reputation.

If you’re a glutton for punishment,

here it is. Beware.

|

|

This means nothing, but I put it here, just in case:

This “Hour of Silents” edition of the movie

was doubled with a MoMA print of The Gold Rush for the Tempe Film Society

at the Community Christian Church, 1700 El Camino Drive, on

Saturday, 17 September 1966.

It was shown at three libraries in the Tri-Cities region of Washington in

March through May 1975.

It then reappeared at the Mayne Williams Public Library in Johnson City, Tennessee, on

Thursday, 2 June 1977.

There were surely countless other such screenings,

and the very thought that people would have been subjected to this defamatory horror

pierces me to the marrow.

|

|

Some listings are confusing.

The version with sound effects shown on

Sunday, 25 May 1975, at the Dahl Fine Arts Center in Rapid City, South Dakota,

then on

Thursday, 18 November 1976, at the Central Library in Burbank, California,

and later on

Tuesday, 16 October 1979,

at the Eagle Rock Valley Historical Society, Eagle Rock City Hall, Los Ángeles, California,

was most likely Killiam’s “Hour of Silents” edition.

|

Stan Brakhage |

|

Are you familiar with Stan Brakhage?

Very famous maker of abstract films, for instance this.

In his book, Film Biographies (Berkeley: Turtle Island, 1977, pp. 181–182),

he told a story that’s worth retelling.

|

|

I was living in Los Ángeles; and I went often to The Coronet

Theatre to see old cinema classics, etc. One night a friend

and I took ‘pot luck’ on whatever The Coronet might be showing.

We were disappointed, on arrival at The Theatre, to discover

‘the show’ for that night was a ‘twenties’ comedy by an

unknown, to us, comedian named Buster Keaton.

We went ‘in for it’ anyway but sat in the back so that we

could easily leave. The title “Steamboat Bill, Jr.” flashed on the

screen; and the first long camera ‘pan’ across an old river town

had my friend and me fidgeting.

But soon some jokes came along to humor us. The gags of

‘The Father’s’ disgust at the sight of his ‘Son,’ played by Buster,

called forth more than usual laughs from me. I’d just been

recently to see my father and had ‘had it,’ the same kind of

reception.

My friend was ‘taken by’ the “Romeo and Juliet’-like

development of the plot, he being involved with “influences of

Shakespeare on our times’ or some-such.

We were ‘guffawing’ along with the rest of the audience

and began, then, to notice a man, sitting in front of us, who

never once laughed. We even made ‘raised eyebrow’ expressions

at each other about it, ‘shrugs of shoulder’ and the like.

Then came the cyclone sequence in the film. A whole town

blows up and down around the hero, buildings falling and narrowly

missing him, etc.; and ‘the house came down’ within The

Theatre, too, everyone laughing more than I’d ever heard before,

myself and friend laughing uncontrollably. When we had time

to notice, between absolute fits of giggling, we saw the man’s

shoulders in front of us rigid as ever, not so much as a tremor of

laugh moving him. We became as amazed by this mysterious

stranger as we were by “Steamboat Bill, Jr.”. Toward the very

end of the film, the man in front got up and turned to leave;

and it was, of course, Buster Keaton.

|

|

To make sense of Stan’s story, we need to pinpoint the date,

and, since the Coronet did not advertise or announce its shows in the newspapers, that becomes a difficult task.

The one time I heard Stan Brakhage speak was on Saturday, 26 January 1980,

at the SUB (Student Union Building) screening room on the UNM campus,

where he introduced five of Buster’s short films and took questions afterwards.

An audience member asked him when Buster was born, and Stan didn’t know.

He said that he never paid any attention to dates. None.

It seemed that he didn’t know the difference between 1820 and 1940.

It was all the same to him.

He explained that he refused to memorize anything he could just as easily look up.

Someone blurted out that Buster was born in 1895,

and Stan was thankful that someone volunteered to answer the question for him.

(Actually, now that I think about it, I’m the one who blurted that out.)

|

|

It is likely that Ray Rohauer had a print of Steamboat Bill, Jr. as early as 1954,

but he had to keep it a secret.

He could not show it to the public.

We know that James Mason recovered Steamboat Bill, Jr., in 1955.

We know that Ray Rohauer made a duplicate in 1960,

and we know that Stan barely knew what century he was living in.

Question: When did Stan’s story take place?

He remembered that it was sometime between 1955 and 1957,

but given the other facts in the case, I concluded that was impossible.

Well, make a monkey out of me.

In earlier drafts I wrote that Stan lied.

He did not lie.

He told the truth.

|

|

When we check on Stan’s dates, we discover that

he was employed at the Coronet in 1956 as

a projectionist and

janitor

in exchange for room and board.

|

|

Elsewhere, Stan elaborated.

When I read his account, I scoffed at it as the most patently obvious confabulation

by a disturbed personality who was trying to get attention.

Now I discover that, yes, he was telling the truth.

Take a look at

“Stan Brakhage Dialogue with Bruce Jenkins, 1999”

(I corrected a few of the more bothersome typos):

|

|

There’s another piece of fantastic luck. That I should be the janitor when Rohauer is getting these films, the rights to

them and getting them transferred out of nitrate into safety film, which he did because MGM [sic] wanted to do The

Buster Keaton Story. One of the lousiest films in the whole history of Hollywood, Donald O’Connor trying to play

Buster Keaton. I was there at these meetings just tagging along with Raymond and Keaton. They’d have these

conferences and Keaton was like what do you call it? He was like reference. What do I mean here? He was the

authority on himself.

O’Connor is sitting there and saying, “Well, in that film The College, how did you do that trick where you turned

somersault and kept the coffee intact, didn’t spill the coffee?” Keaton, who at this point is —

God, he was in his 70’s — he

said, “Kid, I can’t do it like I did it then.” He said, “But I’ll show you a trick, a way you could probably do it.” Then he did

right in front of us this somersault, and he slipped this thing onto a table and picked it up so quickly you could hardly

see. You could have cut three frames out of the movie and you’d never see that it hit the table at all and did this

somersault like that, and ended up with the thing intact and everyone just sat.

|

|

It is impossible to harmonize Brakhage’s story with the latest published chronology,

but Stan’s account is correct and the latest published chronology is mistaken.

It’s mistaken for a good reason, and I was entirely convinced by it, but it is mistaken.

The Buster Keaton Story was filmed in 1956 and released in April 1957.

Rohauer’s involvement in The Buster Keaton Story

was simply to supply the films to Robert Smith and Sidney Sheldon in about March 1956.

That was all.

Interesting to learn that Ray and Stan witnessed any story conferences.

|

|

Stan’s story about witnessing an unlaughing Buster in the Coronet auditorium has the ring of truth to it,

but I was unaware of any possibility of seeing Steamboat Bill, Jr., at any time in the 1950’s,

and so, yet again, I dismissed his account.

Also, I was certain that Buster would have had Eleanor by his side, a detail that went missing from Stan’s telling.

Eleanor denied that she and Buster were at the Coronet

except for that one evening to see The General.

Yet now I learn that, yes, Buster did attend screenings without Eleanor.

Every detail I had scraped together that proved Stan was a liar has now been proven wrong,

and so I have done a 180° on that subject.

I now trust Stan implicitly and I shall accept anything he said.

He has proved his reliability.

|

|

Keep on reading the rest of “Stan Brakhage Dialogue with Bruce Jenkins, 1999,”

because the stories continue, with more details that I found worse than implausible

but that I now accept totally.

|

|

Stan and Ray were friends, but soon enough, most likely because Ray Rohauer was Ray Rohauer, they became enemies,

or something resembling enemies.

Decades later they had some sort of

hesitant rapprochement, but I don’t know the details.

I wonder if Stan ever chatted with Buster at all.

If not, that would not surprise me.

After all, read his chapter on Buster,

and you will discover that his encounters with Buster, which should have remained vivid, were vaguer than vague,

so vague, in fact, that it seems they never exchanged a word.

This is all very curious, yes? No?

|

|

This is my umpteenth rewrite.

Every time I post this sequence of 1955–1960 stories,

I notice that it has contradictory elements — and gaps and impossibilities.

Why?

Part of the difficulty stems from Buster’s abridging and compressing

the story about James Mason and detaching it from the story about Sidney Sheldon,

and then misremembering details.

Buster mentioned this episode twice, in the New York Herald Tribune, 25 July 1956,

and in the New York Post, 11 September 1956.

It is taking me FOREVER to disentangle these separate strands and to patch them back together properly.

Doing so does not mask the gaps in the stories; rather, it throws them into sharper relief.

So, even more challenging is how to fill those gaps,

and, since there is no surviving evidence, I can rely on nothing more than imagination.

Exploratory conjecture is as frustrating as it is rewarding.

I would much prefer to find hard evidence. How? Where?

|

|

A researcher just refuted much of my argument concerning Mason and Sheldon and Rohauer and Meade.

Please allow me a week or so to make corrections.

Stay tuned!

|

|

All right.

We have now gotten far enough along in the narrative and we have examined sufficient evidence

that it is time for you to do a

|

|

A researcher just refuted much of my argument concerning Mason and Sheldon and Rohauer and Meade.

Please allow me a week or so to make corrections.

Stay tuned!

|

|

|

I was optimistic when I learned a few decades ago that Toronto playwright-actress-journalist Eileen Whitfield

was at work on the definitive Buster bio.

I’ve not (yet) read her bio of Mary Pickford, but from all accounts it is superlative, and so Busterphiles were quite hopeful.

There was a title: Buster Keaton.

There was a publisher: Scribner’s.

There was a publication date: 3 January 2006.

There was an

|

|

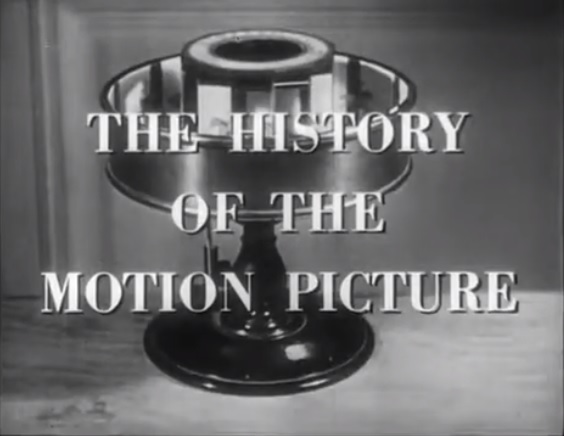

“The History of the Motion Picture”

|

|

Now we learn something astonishing.

The story behind this, I do not know.

Yet we do have some clues, and I shall transmit those clues to you.

If you have more clues, or more information, please share it.

Thanks!

|

|

Let’s return now to

Paul Killiam.

He was a standup comic who had been one of Ray Rohauer’s business partners circa 1954.

They got along famously for about 12 minutes before they began suing one another.

Paul left Ray to continue running his recently founded circulating film collection, Killiam Shows.

|

|

Paul Killiam had created his “Hour of Silents” TV series in 1957 and got it onto a few airwaves in 1958.

The following year, he accomplished yet more, if ‘accomplish’ is the right word.

He hooked up with Saul Turrell’s Sterling Educational Films, Inc., to produce a series of films for classroom use.

This would be called “The History of the Motion Picture,”

which consisted largely of condensations, as before, but more severe.

Rather than running 49 minutes, these would run a mere 25 minutes.

The editor who performed these amputations was, as far as I know, William C. Dalzell.

Whether he had been responsible for the earlier “Hour of Silents” I do not know.

He went straight back to the master copy negatives and cut them, physically,

and he is the one who, as far as I know, compiled the music scores from library recordings.

Which library, I do not know.

I asked Shazam to identify each cue, but Shazam came up with the same response each time:

“No Result.”

If you can identify any of these music cues, don’t keep it a secret. Thanks!

|

|

The intro was narrated by Paul himself, but for the remaining stump of the film,

the great Frank Gallop took over the honors.

|

|

On eBay I chanced upon a 16mm print of this episode of “The History of the Motion Picture”

and I snapped it up right away, for a hundred buckaroos.

It arrived, in its original can and with its original labels, no less!

Alas, I no longer have a projector, and so it is just sitting here on my desk.

I had searched and searched and searched online for “The History of the Motion Picture,”

and I found a whole bunch of episodes, but not The General.

I searched under “Killiam” and I searched under “Sterling Educational” and I searched under “Sterling Films”

and I searched under “Silents Please” and I searched under “History of the Motion Picture”

but there was nothing nothing nothing nothing nothing.

Then, just now, when I searched simply under “Keaton The General” I got a hit!

Here it is, a battered copy, very choppy, missing a total of about three minutes:

|

|

Public Domain Movies, Buster Keaton - The General (1926) https://youtu.be/lbzorV_jEW8 also available at https://archive.org/details/thegeneral_201512 and at https://youtu.be/xtaQ_L9oEOc. When YouTube disappears this video, download it. |

|

What a mess!

The abridgment ruins the film, the needless narration ruins it even more, and the music ruins it yet even more.

Whoever made this film-to-video transfer for YouTube mistakenly turned on the cheap motion stabilizer,

and cheap motion stabilizers really don’t do the world any good.

|

Cinema Theater (formerly Lyric),

|

|

This was a 35mm print.

In the US at the time, there were no 35mm prints of The General for rental.

Where on earth did that print come from?

My guess is that it was an unclaimed leftover from a disused UA exchange.

If my guess is correct, then Earl likely traded for it with another collector.

Was this perchance the tinted 1926 original that David Shepard found more than thirty years later?

Unlike many nitrate prints, the print that David discovered seemed still to be in good, projectable condition,

or, at least, parts of it so seemed,

and that is how he managed to run it through a scanner.

I so wish we had more information about the print that Earl showed from 16–18 June 1960.

This here Earl Noah “Buck” Manbeck, Junior

(8 Nov 1921 – 20 Jan 2007),

feller was an odd one, eccentric, Iowa’s iteration of Jim Card.

See

“Earl N. Manbeck Finds Movie Hobby Is Fun,”

Boxoffice vol. 62 no. 13, Saturday, 24 January 1953, p. 73;

“Des Moines — Earl Manbeck, local exhibitor,” Exhibitor vol. 50 no. 5, sec. 1, 3 June 1953,

|

|

Silents Please |

|

Paul failed to get his “Hour of Silents” series onto a US network,

but he did get his series of 25-minute abridgments into classrooms.

Could he merge the two ideas?

Yes!

He proposed a new TV series,

Silents Please, which was merely “The History of the Motion Picture”

but with different opening and closing credits.

He found a sponsor, perhaps several sponsors, and went to town.

Each 25-minute abridgment in the series was narrated, sometimes by Paul himself and sometimes by the great Frank Gallop.

The show premièred on Thursday, 4 August 1960,

and the second episode, Thursday, 11 August 1960, was the condensation of The General.

Upon the broadcast of the tenth episode on 6 October 1960, ABC canceled the series.

|

|

I recently purchased a 25-minute abridgment of The General, distributed by

Sterling Educational Film, “Produced and Written by PAUL KILLIAM and SAUL J. TURRELL,”

with a 1959 copyright notice in the name of

Gregstan Enterprises, Inc.

The bottom parenthetical line: “(Not to be exhibited on Television).”

This was from the “The History of the Motion Picture” for use in classrooms.

I do not know how to read the Ferrania edge code: •••■

|

|

Though I have seen a Super 8 silent print of the 25-minute version of The General, and

though I have now finally seen the episode of “The History of the Motion Picture,”

yet I have never seen the “Silents Please” TV episode.

Should it ever turn up, it will probably contain a surprise or two.

It is most interesting that

the closing credits to at least one of the episodes name

as consultants Theodore Kupferman and Richard Griffith, curators of the Museum of Modern Art Film Library.

Did those two consultants recognize where some of Paul’s prints came from?

Altogether, these uploads indicate that all the materials likely still exist somewhere.

|

|

It is doubtful that Buster watched this episode of the TV show,

though he certainly learned about it soon afterwards.

He was not happy about it, as we shall see below.

|

|

ABC renewed the license and brought the series back in January 1961,

now hosted by

Ernie Kovacs, who, alas, never recorded an introduction for The General.

ABC once again canceled the show upon the broadcast of Series 3, Episode 5, on 6 October 1961.

Kovacs died in a car wreck on Saturday, 13 January 1962, and that spelled the end of the series,

as far as the network was concerned.

Saul Turrell and Paul Killiam then sold the old episodes to individual stations

and continued recycling episodes of “The History of the Motion Picture” for the TV series,

presumably with Gloria Swanson offering brief intros.

Gloria offered an intro to rebroadcasts of the 25-minute edition of The General,

and, as far as I can tell, her intro appeared only five times:

Saturday, 18 May 1963, Sacramento, KCRA Channel 3

Saturday, 8 June 1963, Los Ángeles, KCOP Channel 13 Saturday, 13 July 1963, San José, KNTV Channel 11 Thursday, 8 June 1972, San Francisco, KPIX Channel 5 Saturday, 30 December 1972, Detroit, WWJ Channel 4 |

|

Cinecinéfilos films

Gloria Swanson presenta “El maquinista de la general” (“The General”) Dec 14, 2019 Click to play |

|

Out of curiosity, I decided to trace “Silents Please” —

well, as best as the fragmentary newspaper listings allow.

As you see, some of these episodes are online,

some of them in English [Eng] and some of them in Spanish [Spn],

some of them from “History of the Motion Picture” [HMP] and

some of them from “Silents Please” [SP];

one of them only a momentary fragment,

all of them battered terribly.

|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

This series was once offered on VHS, which I find surprising.

I had never seen it on offer anywhere.

Here is an amusing recollection posted on

IMDb.

This note got one thing backwards, understandably.

“The History of the Motion Picture” came before “Silents Please.”

Anyway, enjoy:

|

|

Many of the “Silents, Please” episodes turned up — sans Kovacs —

retitled as “The History of the Motion Picture” and were made available to public libraries in the 1960s.

All footage was public domain.

They were released on VHS in 1997 from Critics’ Choice Video in transfers made from old ragtag prints,

some with

|

|

I guess that most of what we find online was just uploaded from those commercial VHS tapes.

And I suppose the VHS tapes were sourced from school-library discards.

|

The UK Film-Society Print |

|

We learn that The General

was a popular rental item to British film societies,

but who was the distributor?

I asked around.

The BFI was clueless.

This required yet more research.

The 16mm market in the UK was pretty much cornered by two firms.

The first was

Plato Films, Ltd. (247a Upper Street, London N1 1RU), founded by

Stanley

Forman in 1950.

For legal reasons, this became

ETV (Education and Television Films).

I have not seen a catalogue, but I understand that Plato’s concentration was on Communist films, not entertainment.

A second company, founded the following year, took care of the market for entertainment films.

It was called

Contemporary Films, Ltd. (8 Dickenson Road, London N8 9EN), founded by Charles Cooper in 1951.

The current executive at Contemporary is quite sure that The General

was never in his company’s catalogue.

Contemporary put me in touch with a researcher who suggested some other possibilities:

Gala Film Distributors, Ltd. (30 Tottenham Court Road, London W1), and

Connoisseur Films, Ltd. (167 Oxford Street, London W1,

|

|

Oh heavens to Betsy!

I found the distributor!

The BFI!!!!!

The BFI is apparently divided into two departments: archive and distribution.

The staffs of the two divisions seem never to meet, socialize, or even to bump into each other in the lunch room or in the corridors.

They probably use opposite entrances to get into the building,

and it actually seems that each department is unaware of the other’s existence.

The BFI seems not to have had The General available for distribution in

early 1955, but the film was certainly available for distribution by

September 1961 (see also

this)!

Actually, considering that it made the cover that month, that was surely when it was introduced into the catalogue.

Prints were available in 35mm, 16mm, 9.5mm, and 8mm.

Now, from whence did the BFI acquire this film for rental?

The BFI circulation department has zero interest in responding to my enquiries, and so I am left again to guesswork.

My guess is that the BFI ordered a lavender from the UA London office.

An alternative guess, at least as likely, is that the BFI ordered a copy negative from MoMA.

It seems that these circulating prints and their master have vanished from the face of the earth.

If you can locate any of these materials, even a single frame, please let me know. Thanks!

What is the true story, and what is the reason for that true story?

The truth will be revealed nel suo tempo.

|

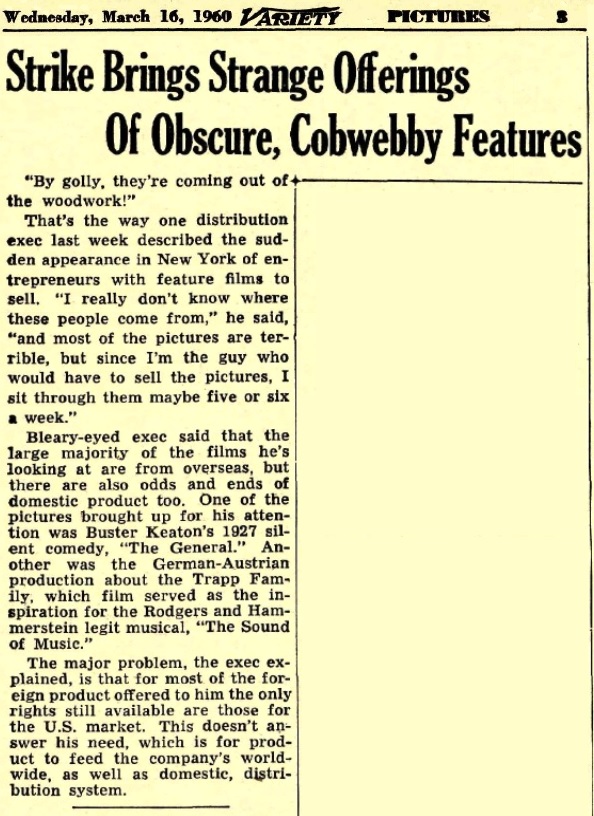

Cobwebby Features |

|

All parties are anonymous in this bizarre story from the weekly Variety.

Someone claimed to have been offering The General for distribution to US cinemas.

Who?

Was it Rohauer who was offering this?

He had a dupe negative that he needed to amortize, and the film was by now in the public domain in the US.

The only commercial entities with 35mm materials were MGM and Raymond Rohauer,

and so my guess is that this was either MGM or Rohauer.

Since MGM seemed pretty much unaware of its possession of a lavender,

my best guess is that this was Rohauer.

Or, ya know, maybe not.

Could this have been Paul Killiam offering his 49-minute “Hour of Silents” edition?

If so, that would explain why no distributor placed a bid.

I bet it was Killiam. I bet it was Killiam. I bet.

|

|