The British Film Institute

|

|

This happened really quickly.

In January 1953, the BFI received a gift of a brand-new 35mm diacetate print of The General.

I have been assured that there are no surviving records to indicate who made this donation.

Since I cannot see the records, I am, yet again, reduced to making guesses.

My guess: United Artists, probably the London office, made this print most likely directly from the camera negative.

It was most likely the export edition, but that is not certain.

|

|

Oh my, am I ever too hasty!

The BFI did not receive a print.

It received a fine-grain, a “duplicating positive.”

From that duplicating positive, the BFI ordered a copy negative from which it made a print.

Click

here for a little

|

|

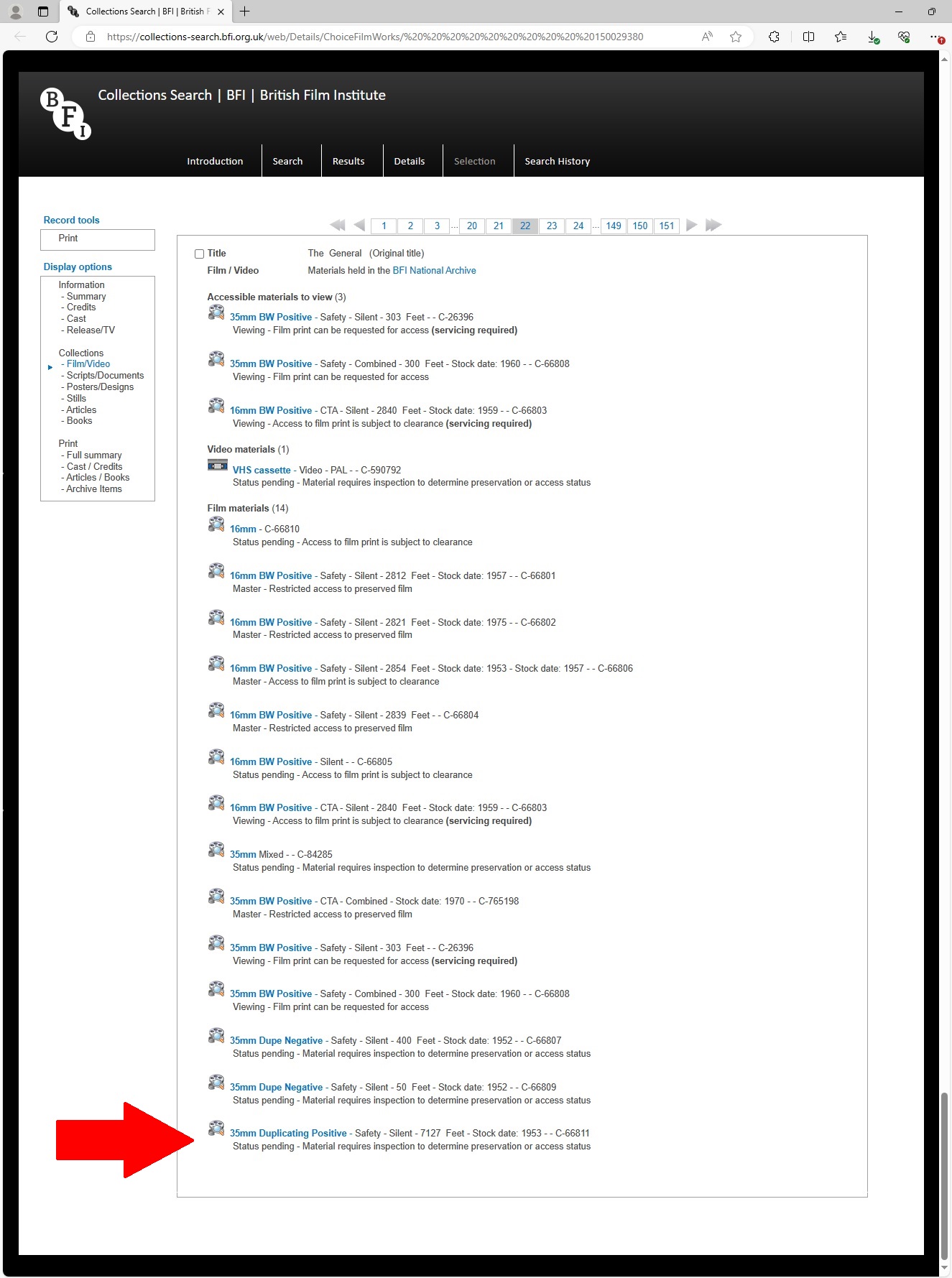

Let us take a look at the BFI’s card catalogue.

If you want to go to the catalogue yourself, first

click here to unlock the library catalogue so that you can reach

this page.

|

|

|

See? It’s a duplicating positive.

The length of 7,127' seems about right.

That would be the 7,084' of film that reaches the screen

plus the Part Titles and maybe leaders and tails that would usually not reach the screen.

The difference of 43' (about half a minute) could also be the result

of this being the export edition rather than the US edition,

shot on a different camera with a slightly different cranking speed.

Note that the corresponding projection print is 16mm.

There is no copy negative, and heaven only knows what may have happened to that.

Maybe the cataloguer simply forgot to index it?

Oh duh. I’m not thinking.

What if the 16mm projection print was a reversal?

I bet it was. I bet it was a reversal (no negative needed).

|

|

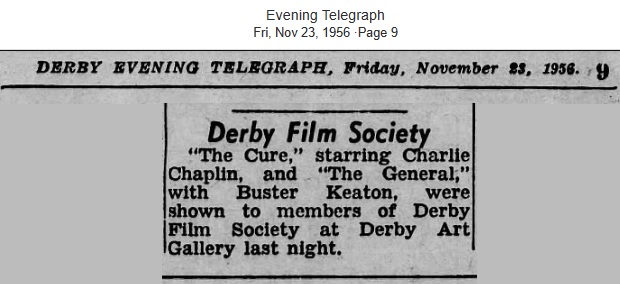

The BFI, immediately upon receipt of this gift, scheduled some screenings.

|

|

To judge from the above blurbs, this would seem like a one-week booking,

beginning on Sunday, 18 January 1953, followed by one-week bookings of five further films.

That is far from definitive, though.

By the time this news reached the States, the event was long over:

|

Mysterious British Appearances |

|

By 1953, The General was no longer commercially available in the UK,

and no 16mm distributors offered copies to film societies.

That is why we are surprised when we find the following:

|

Frodingham Parish Hall, 5 Church Lane, Scunthorpe DN15 7AB. Capacity: 160. The Hall first opened to the public on Monday, 15 September 1952. |

The Derby Museum today is different from the Derby Museum in 1956. If you have any photographs, especially of the screening room, please send them along. Thanks! |

Concert Hall first opened to the public on Saturday, 19 March 1927. 750 seats This is where the Bournville Film Society held its screenings every third Tuesday at 7:15pm, tickets 10/-. |

|

(New) Shakespeare Theatre, 14-3 Fraser Street, Liverpool. Capacity: over 3,500.

Opened to the public on Monday, 27 August 1888,

absolutely fireproof.

Largely destroyed by fire on

Sunday, 21 March 1976, condemned on

Thursday, 1 April 1976, and demolition completed probably by

Image shamelessly stolen from ArthurLloyd.co.uk,

Liverpool Theatres Index.

|

|

Had there been only a single film-society screening of The General during these years,

I would have guessed that the print was borrowed from overseas.

But there were four screenings — at least four screenings —

by at least four different British film societies.

My only guess is that they borrowed the BFI archive’s 16mm print.

As a matter of fact, there is some circumstantial evidence to suggest that was indeed the case.

Scroll back up and look at the archive catalogue.

Note that item

|

Australian Appearances |

|

The

June 1955 Sydney Film Festival in Australia presented The Navigator,

and I can only assume that was a leftover print from the local exchange.

A year later, the Festival presented The Balloonatic, and, again, I suppose it, too, was a leftover print from the exchange.

The Navigator returned for a film-society meeting in

January 1961, and I suppose that was a 16mm print, but from who-knows-where and copied from who-knows-what.

I bet it was from a copy negative purchased from MoMA.

It returned for a club showing in

March 1964 and was back again for a film-society screening in

May 1964.

So, in Australia, at least, there was some

fond memory.

I wonder if those particular prints of The Balloonatic and The Navigator still exist.

(And can somebody please make me feel either better or worse by

telling me how the bears were wrangled in The Balloonatic?)

|

The Coronet Theatre |

|

This is a tangent, and yet it is crucial to understanding Buster Keaton’s career,

even though Buster only rarely stepped inside this building.

|

|

The Coronet, 272 seats, was built in 1947 and presented both occasional live entertainment but mostly films.

Film screenings had to go on hiatus for a few weeks or months whenever a theatre set occupied the stage.

Paul Ballard, who had run his Film Society out of his apartment,

moved his program to the Coronet and redubbed his organization

the Hollywood Film Society.

He began his Coronet film series on 5 May 1947.

To read a little bit about and by Paul Ballard, click

here and

here and

here.

I was able to take snapshots of some of the programs.

|

|

If this does not display,

download it.

|

|

It seems to me that these film presentations were all 16mm

and that most or all of the films came from MoMA.

It appears that Raymond Rohauer was involved in this from the earliest days,

but I cannot be certain of that.

|

|

A month after Ballard’s film series opened,

the Coronet opened its first stage presentation,

Thornton Wilder’s The Skin of Our Teeth on

Wednesday, 11 June 1947.

Its second stage production was the world première of Brecht’s Galileo on

Wednesday, 30 July 1947.

|

|

It was sometime in 1950 that Ray Rohauer established the nonprofit Society for Cinema Arts,

which took over the function of Paul Ballard’s Hollywood Film Society.

Precise details elude me.

For some background, you can read the Los Ángeles Department of City Planning’s

RECOMMENDATION REPORT

for the Cultural Heritage Commission.

It’s a good read with a good history.

|

Raymond Rohauer |

|

You are about to start running into lots of mentions of a certain Raymond Rohauer.

As an introduction, here is a little video.

It is inaccurate, but it will give you a pretty fair idea

of the Commonly Accepted Knowledge concerning this certain Raymond Rohauer.

And remember: Commonly Accepted Knowledge is usually wrong.

|

|

OddityArchive, Oddity Archive: Episode 208 — The Ballad of Raymond Rohauer, posted on Dec 10, 2020. When YouTube disappears this video, download it. |

|

Now, I have been taking time off to plough through holdings at an archive,

where I am promised tons and tons of dirt on this certain Raymond Rohauer.

As I dig through the holdings, I am finding exactly no dirt on Rohauer.

None. Zero. Zilch. Nada.

The bulk of the horror stories I have read and heard through the years are dissolving before my very eyes,

dissolving into nothingness.

I am finding lots of unsavory information, though, about his critics.

Now, Rohauer was no angel, and he was certainly peculiar.

He could be really nasty at times and he certainly had some bizarre quirks.

The result was that, as far as I know, he had no close friends, save one Kristian Chester.

His alterations of the films under his care irk me no end and I consider those changes to be sheerest vandalism,

and yet I understand the paranoia that led him to commit those atrocities.

As for all the evil that is supposedly lurking in the background, well, it ain’t there.

So, please be careful.

As for the calumnies I have scribbled onto the various pages of this website, well, I apologize.

I shall scrub them away over the next couple of weeks.

For the record, Ray Rohauer did NOT copy any films he rented from MoMA or any other distributor.

That is an absolutely baseless accusation that has been going around for far too many decades.

Instead, he did something else entirely, something that drove everybody crazy,

something that aroused hatred and indignation everywhere,

something that will earn him a favored spot in history as the centuries drag on.

I say it elsewhere and I say it here again:

History will be kind to Raymond Rohauer.

|

|

Live performances continued as before, under the sponsorship of John Houseman’s Pelican Productions.

Films continued as well, under the sponsorship of Rohauer’s Society of Cinema Arts.

When did the Society of Cinema Arts take over from the Hollywood Film Society?

My best guess is Wednesday, 1 November 1950, but I really cannot be sure.

The SCA concentrated largely on experimental,

|

|

The Coronet was 16 blocks from of John and Dorothy Hampton’s Movie: Old Time Movies.

Artsy places need to be in Bohemian neighborhoods,

and yet these two movie houses were rather out-of-the-way in the antiseptic suburbs.

Surprisingly, they each somehow attracted a loyal clientèle.

That would seem impossible, and yet it happened.

|

|

Now, I had searched and searched and searched and searched and searched

for months and months and months and months and months

in all the available LÁ periodicals

for any advertisement, any announcement, of Rohauer’s programming at the Coronet — all to no avail.

There was the occasional passing reference, together with plenty of items about the stage shows,

and, of course, articles about the vice squad raiding the place (for two films that displayed no vice),

but there was nothing about the film programming.

|

|

The two movies that were busted?

Fireworks and

The Voices.

They leave me totally cold and I find them hopelessly dull, but some folks like ’em, so hey.

Did you click on the links and watch them?

Did they scandalize you?

Did they corrupt you?

Did they lead you down path of perdition?

As for the accusation that the Coronet was popular among “homosexuals,”

well, so is any place that exhibits fine arts.

The artistic crowd tends not to give a hoot about people’s hormonal balances,

and so it’s a crowd that can serve as a good refuge for those who wish simply to unwind and be themselves.

The implication that the Coronet was a hotspot for perverts was preposterous.

Please, folks, please stop saying that, now.

(I use quotation marks because the word is an adjective, not a noun, despite popular usage.)

|

|

Anyway, the utter lack of publicity convinced me that it must have been a private club that never advertised.

What I did not realize is that there was one newspaper, probably only one,

that accepted advertisements for and press releases from Rohauer’s screenings at the Coronet.

Well, that changes my story, doesn’t it?

This was a newspaper I had never heard of before, the Los Ángeles Evening Citizen News.

But the advertisements and press releases ceased after a mere few months.

A second newspaper, the Daily News, also made a few rare mentions of Rohauer’s programming,

but I had never caught it before, surely because it had not yet been OCR’d and indexed.

|

|

So, here we go. Below is a scrapbook, but it is not yet complete.

It is a scrapbook in progress.

As I find more, I shall add more.

Use the scrollbar or the mousewheel on the below window to go through the various clippings.

Not all the clippings mention the Coronet, but I include them for context.

|

|

If the above scrapbook does not display,

download it.

|

|

Might you have any Coronet-Louvre / Society of Cinema Arts programs in your collection?

If so, please let me know.

I shall happily pay for scans, which I would like to post here.

I have seen only a few, poor thermal photocopies of poor thermal photocopies,

and further copying is strictly forbidden.

|

|

A researcher just refuted much of my argument concerning Mason and Sheldon and Rohauer and Meade.

Please allow me a week or so to make corrections.

Stay tuned!

|

James Mason |

|

Now we delve into a terribly confusing story.

This story had not been confusing before.

The story, as I had understood it, was remarkably simple.

Here. Let me show you.

The first I knew about the story was from Rudi Blesh’s book on Keaton published by Macmillan right at the beginning of May 1966.

This is how Rudi told the story (p. 368):

|

|

The Italian Villa had gone through many hands. Natalie Keaton

sold it in 1933. Fanchon and Marco lived there, Barbara Hutton,

a millionaire glass manufacturer, and, during a more recent period,

James and Pamela Mason. It was Mason who, in 1955, happened on

the secret panel to a film-storage vault behind the private projection

room of the Villa. There, untouched for twenty-two years, was a

cache of films — all of Keaton’s own features, from the first, The Three

Ages, to the last, Steamboat Bill, Jr., plus a good number of the shorts.

|

|

¿Simple story, que no?

Tom Dardis offered his own version (pp. 272–273):

|

|

Other Keaton films were found in the Italian villa, which

had passed through a number of hands after its purchase by Fanchon

and Marco. It was acquired in the fifties by the actor James

Mason and his wife Pamela. To his considerable surprise, Mason

discovered that the small projection room that Buster had used

to show films to his friends contained several dozen cans of film,

positive prints of high quality. It was this find, together with the

negatives and positives from MGM, which allowed for the eventual

rerelease of many of Keaton’s films....

|

|

Marion Meade also tried her hand at the same story (pp. 255–256):

|

|

Through the Italian Villa over the years had come and gone a

number of celebrities: the dance team of Fanchon and Marco,

Barbara Hutton and Cary Grant, Marlene Dietrich and Jean

Gabin, members of the Libby glass family. Just a few yards from

the main entrance stood Keaton’s tiny cutting room, where work

prints had been forgotten during his hasty exodus in 1932 and

whose original use remained unknown. Subsequent tenants and

their gardeners used it to store wheelbarrows and lawnmowers.

In 1949 the Italian Villa was purchased by James Mason, one

of England’s best-known movie stars. Seven years passed before

Mason and his wife got to poking around in their dirt-floored

toolshed and examining a rusting safe. It turned out to be

crammed with film. “We were horrified to find Keaton’s old films

rotting away in there,” said Pamela Mason. James Mason began

running his favorite Keatons until some of the sprocket holes

started snapping. At that point, he decided he must do something

about preservation, and he donated some of the Keaton films to

the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences.

Word of Mason’s treasure soon got back to Rohauer, who

urged Keaton to demand the return of the films. In fact, Keaton

did apparently turn up unannounced one day in spring 1956, his

first return to the Italian Villa in twenty-four years. The Masons

had changed the name of the street from Hartford Way to Pamela

Drive. They had also sold most of the land out of economic necessity,

and the property had been subdivided. The house that had

once overlooked a sweeping emerald lawn and robin’s egg-blue

swimming pool now looked over a row of ordinary backyards

belonging to ordinary Beverly Hills houses. When he rang the

bell, a maid informed him that Mason was not at home. Keaton

believed that he refused to show his face. “Mason wouldn’t come

to the door and the maid said I couldn’t get the film,” he told

New York Post reporter Jim Cook a few months later. He felt

humiliated and called his treatment “a crowning indignity.”

For James Mason, Keaton’s demand presented a dilemma.

Should he return the work or preserve it? Eventually he decided

that Keaton did not possess the facilities for preservation and

could never derive any financial advantage from having his films

anyway. He chose the Academy, but Rohauer subsequently persuaded AMPAS to return the films to Keaton.

Accompanied by Rudi Blesh, Keaton returned to the Villa for

films not given to AMPAS. Inside the house he found alterations

even more striking than those made to the grounds. Exquisite

chandeliers had been replaced. For the Mason children, the original

Oriental carpets had been removed and the marble and oakwood

floors covered with cork. There was also acoustical tile lining

the ceiling of the drawing room, which Pamela Mason used to

broadcast a radio show. Dozens of cats roamed freely through the

house.

At home, Keaton carried the film cans into the kitchen and

unpacked the nitrates as nonchalantly as a bag of groceries. There

was a cutting copy of The General, as well as a number of Keaton’s

earlier shorts, including the only print of The Boat that would ever

be found. As it turned out, The Boat was almost beyond redemption.

Once he had screened the pictures, he turned them over to

Raymond for transfer to safety stock.

Shortly afterward Keaton phoned the Masons to ask if he

might bring his wife around to visit. Pamela Mason, embarrassed

about the alterations she had made, refused. “I ruined his beautiful

house,” she said. “But I was young and didn’t understand that

the place was historical. I was afraid — what if he had told his wife

about his grand house and then she walked in and saw the cork. It

would have broken his heart.” Keaton did not ask a second time.

|

|

Probs probs probs. Delusions? Or outright lies? Or both?

Meade interviewed Pamela Mason by telephone, but she published just a few selected quotes,

and the story above cannot possibly reflect what Pamela Mason said.

Meade just made stuff up.

You didn’t digest that. Let me state it again.

MEADE JUST MADE STUFF UP.

|

|

Let us go through some of the problems in Meade’s narrative.

The first problem is the one that instantly set all my alarm bells clanging.

Nobody else on the planet seems to see any problem with this preposterous claim, and that just leaves me dumbfounded.

This is a perfect example of why I have such difficulty when having conversations with anyone other than my cat.

Nobody seems to understand reality.

Let me explain reality, with links to videos that will show you reality, quite vividly.

|

|

A researcher just refuted much of my argument concerning Mason and Sheldon and Rohauer and Meade.

Please allow me a week or so to make corrections.

Stay tuned!

|

|

PROBLEM 1: The idea that the Masons would have projected the films is extremely unlikely.

Most readers seem to see nothing wrong with Meade’s assertion.

Most readers seem to accept Meade’s assertion

because most readers seem to have some vestigial memories of running 16mm projectors in high school

or of seeing daddy run Super 8 home movies in the living room on Sunday nights.

¿Easy peasy, que no?

That is not the same thing at all. At all. At all.

There is something seriously wrong here.

Just because Pamela and James acted in movies, it is hardly likely that they were technicians.

A few actors were.

Buster was, most definitely.

So was Roscoe Arbuckle.

So was Oliver Hardy.

But most actors were not technicians.

Most actors would have been totally helpless if told to project a film.

You don’t believe me.

|

|

Here is a projectionist showing a movie. Watch the video all the way through, please.

When YouTube disappears this video,

download it.

|

|

Looks totally intimidating, doesn’t it?

Well, honestly, it’s not hard work.

Almost anybody could learn the basics of the job in a few days.

If you’re not trained, though, you can see that you wouldn’t know what on earth to do,

you wouldn’t know even which switch does what.

You would be totally clueless.

But Marion Meade here might have an out.

|

|

Buster’s villa, because it was Buster’s, included a screening room.

As a matter of fact, when Pamela and James moved in, Buster’s projectors were still there.

They were smaller machines that would not be used in a cinema,

but that would instead be used in a small screening room or in a military situation.

They did not have carbon arc but 1000W incandescent light sources.

They were Simplex Acme, first put on the market in

1931, and Buster purchased them not long before he left the villa forever.

(Thanks to Richard Adkins and Bill Counter for the research on these machines!)

Now, let us interrupt the narrative to look at Buster’s projectors.

|

|

fernando, Proyectora de cine simplex acme 1939, posted on Dec 10, 2018. When YouTube disappears this video, download it. This is a somewhat later model. I am thrilled that I finally get to see the gear mechanism! Oooooooooooooooooooooooooooo! Beautiful design! That is the sort of design, I think, that, if we never service it, never open it, never adjust it, it should last 20,000 years and continue to run flawlessly. I need to save me pennies and get me a couple of these contraptions. |

|

So, Buster had a booth and a screening room,

and the booth was surely rated to contain fires and explosions.

Okay. Fine.

Could Pamela and James have operated these machines?

Most likely, since they were so simplified and already installed.

There’s still a major problem.

|

|

A researcher just refuted much of my argument concerning Mason and Sheldon and Rohauer and Meade.

Please allow me a week or so to make corrections.

Stay tuned!

|

|

PROBLEM 2: The films were nitrate, yes, but not just nitrate.

They were between about 25 and 35 years old,

decayed and brittle from having been exposed to high and low temperatures, high and low humidity.

Running such physically compromised films would have posed a

lethal risk of fire, and the Masons knew that.

Suppose, for the sake of argument, that the Masons did not know that.

It would therefore follow that they did not know how to operate 35mm projectors,

and so they would have needed to hire a projectionist to go to their house and entertain them,

or they would have had to book a screening room in order to watch the films.

Now, watch this video of some portable machines running a new nitrate print in good condition:

|

|

HuntleyFilmArchives, Nitrate Film Handling, 1940’s - Film 6416, posted on Sep 15, 2014 When YouTube disappears this video, download it. |

|

Did you watch that video?

Did you watch it all the way through?

Good.

Would you hire a projectionist to run brittle and degraded nitrate films in your house?

Even if the projectors were placed inside a fireproof concrete booth with explosion vents?

No projectionist anywhere on the planet would have projected those films.

Upon attempting to wind those cores onto reels, even the most uneducated, foolish, suicidal projectionist would have said,

“It’s too far gone.

I ain’t touchin’ this stuff.

You need to get it copied if you want to see it.”

The best way to view those films would have been on a flatbed editor,

and even that would have been too risky.

Anyway, I just cannot believe that the Masons had a flatbed editor at home. Preposterous.

What on earth would they have needed it for?

They didn’t have one. I am willing to wager money that they did not have one.

So, were Pamela and James foolish enough to lace up badly compromised 30-year-old nitrate prints

and project them in their home?

I really doubt it. I really, really doubt it.

|

|

PROBLEM 3: Buster never got inside the villa again after 1932.

PROBLEM 4: All the films had been donated to the Academy, and so Buster did not return to pick up the leftovers.

PROBLEM 5: Buster did not take any of the films home.

PROBLEM 6: Rohauer did not persuade the Academy to return the films to Buster.

|

|

Like I mentioned above, this is typical for Meade.

Every page of her book is riddled with such errors.

She just made stuff up.

Repeat: SHE JUST MADE STUFF UP.

She made guesses based on previous misinformation,

and then she made wild guesses about ways to link the various lies together,

and then she assumed her reconstructions must be right, and so she printed them as fact.

When her reconstructions contradicted previous accounts, she dismissed those previous accounts and often let them go unmentioned.

Worthless rubbish.

This is not an occasional problem that pops up two or three times in her volume.

No.

It is a ubiquitous problem that infects every paragraph of her book.

At least when I make guesses, I clearly label them as such,

and I try to fit them to verified facts rather than just accept other people’s fibs as reliable accounts.

|

|

There is no way under the sun that Meade’s claims can withstand scrutiny.

At this stage in this narrative, you do not know that for certain.

Meade’s claims are in a book that has gone through several printings,

a book that is highly regarded and that is used as a source by prominent encyclopedias.

I, on the other hand, am a nobody, entirely lacking in credentials,

with only a few minor publications to my name, screaming objections from a vanity website.

This is yet another example of

|

|

There is another version of the Mason/Keaton story.

|

|

There is another version of the Mason/Keaton story.

|

Thanks to Olga Egorova for locating this article for me! |

|

There is another version of the Mason/Keaton story.

|

|

There is another version of the Mason/Keaton story.

Open the Jim Curtis book and turn to page 577.

|

|

James Mason, who would later claim he was out of town when Keaton

appeared at his door, apparently summoned a locksmith to open the vault.

Inside were nine of the ten features Keaton made for Joe Schenck, and seven

of his best

“A dilemma presented itself,” he wrote. “Should I make a respectful

humane gesture towards the great artist? Or should I guarantee the preservation

of the films? I knew that Keaton could not use the films to his

personal advantage and that he did not command the facilities for preserving

them. Anyway, right or wrong, I chose [to donate the films to] the

Academy.” And so in January 1956, the Academy of Motion Picture Arts

and Sciences took delivery of the entire contents of Buster Keaton’s former

vault, which included 35mm prints of The General, The Navigator, Three Ages,

Go West, Cops, The Boat, and Sherlock Jr. For his trouble, Mason awarded

himself a $10,000 deduction on his federal income taxes.

|

|

Where does the above story come from?

We turn to the endnotes and our collective heart sinks.

It comes from Raymond Rohauer, “Buster Keaton and the Race against

Time, or Where Have All the Comedians Gone?” Notes for the National Film Theatre

of London, 1968.

That puts us at least two removes from the source of Mason’s quote.

A Google search reveals that this essay is freely available

online, but in almost illegible quality.

Five pages of relentless blur.

So I retyped it for you. Aren’t I nice?

|

|

|

|

You surely noticed the content and style and argumentation of the above piece.

It should not require a Ph.D. in psychology to determine from his brief essay that Ray had a character disturbance.

Now, Ray told countless fibs in his time, and some of those fibs are indeed in the above piece,

but the letter from James Mason is surely authentic.

The style and grammar have all the hallmarks of James Mason’s erudition,

and that was not something that Ray would have been able to fake if his life depended upon it.

|

|

Do we have confirmation that Mason donated the films to the Academy

and did not hand them over to Buster?

Look at Jim Curtis’s book, pages 611 and 612,

and there is sufficient detail to convince any doubters.

Nonetheless, I shall eventually find the original documentation.

I am certain it still exists.

|

|

There is another version of the Mason/Keaton story,

this one by Eleanor herself, as she told it to Marion Meade.

Olga Egorova, once again, supplied this gem.

|

|

Marion Meade: Right. Let me get... Let me start at the beginning with Ray.

When you first met him, what was your impression of him? He was quite young then.

|

|

|

Eleanor Keaton: Oh, yeah. He was very young.

|

|

|

Marion Meade: He was a young.

|

|

|

Eleanor Keaton: He was just a avid film fan, is all you could say.

He was running, managing the Coronet Theater on La Cienega.

|

|

|

Marion Meade: Is that the one... I thought... Like a studio. Right.

|

|

|

Eleanor Keaton: In the front. Yeah. Lovely theater inside, 750 seats, I think.

|

|

|

Marion Meade: Is it still a theater?

|

|

|

Eleanor Keaton: Oh, yeah. They do real shows in there now.

Anyway, we saw an ad in the paper that they were going to be doing The General.

Buster says, “Let’s go see it in a real theater.”

In fact, I don’t think I’d ever seen it.

“Let’s go to the movies.”

So we went to the Coronet and paid our two dollars.

Christian Chester, the old man, his “adopted father,” Raymond’s —

|

It was not advertised in the paper. It was a private, members-only screening, announced by mailed flyers.

The payment must have been for a temporary membership.

The correct spelling is Kristian Chester.

|

|

Marion Meade: I didn’t know who he was. I didn’t know —

|

|

|

Eleanor Keaton: Raymond’s parents were killed when he’s not too old,

and Chris practically raised him, I guess. Of course, he was a friend of the family.

|

Ray was born out of wedlock on 17 March 1924.

His mother was Rose Mary Fiebelkorn,

5 July 1893 in Buffalo through 18 May 1952 in Los Ángeles.

She bestowed the father’s surname upon Raymond.

I am not certain, but his father was most likely William J. Rohauer, born circa 1904,

who passed away of asphyxiation by gas on 17 December 1925.

Kristian and Ray first met in Los Ángeles in the |

|

Marion Meade: I see.

|

|

|

Eleanor Keaton: And then I found out later, after Raymond died,

he had a |

|

|

Marion Meade: So you went and you saw —

|

|

|

Eleanor Keaton: We went... Chris saw us and recognized Buster, of course.

So we went on.

At the end of the movie... Because Raymond was running a projector up above,

and at the end of the movie, he’s up there like this and started talking and this and that.

And Buster said, “Well, I got a bunch of films in the garage. You can have them if you want them.

They’re only going to sit there and spoil.”

Of course, he came to the house, and that started it.

|

|

|

Marion Meade: You were living in Cheviot Hills?

|

|

|

Eleanor Keaton: No, Myra’s house on Victoria.

|

|

|

Marion Meade: Right.

|

|

|

Eleanor Keaton: That started that.

Then he went from our original six or eight films, whatever it was we had, it started...

Then he found...

James Mason called Buster and said, “I’ve just got into the...”

It was a secret storeroom with a...

You had to hit the wall in a certain spot to open it,

and they found it after they’d been looking there a long time.

He found all kinds of film in there, including some of Buster’s.

He said, “You want them? I’m going to get rid of them.

I want them out of there, because they’re old nitrate.

They could explode.”

So Buster, at that time, called... I think Rudi Blesh was out working on the book at that time,

and the two of them went up and retrieved all the films and brought them back

and viewed them and gave them to Raymond to be cleaned up and transferred safety stock and whatever.

That gave Raymond a few more.

By then, he has about 10 or 12 all together, and then he went collecting from there.

|

James Mason never called Buster.

It was Buster who attempted to call upon James Mason, at the request of MoMA.

Rudi and Buster did not retrieve the films,

as Mason had arranged for them to be donated to AMPAS.

Eleanor paid next to no attention to this development,

which is why her memory was so poor.

|

|

Eleanor Keaton: The last thing he found, Kevin Brown and David put together, was Hard Luck.

The first time anybody saw that, including me or anybody else,

was at Palladium in London where I was there three years ago.

I guess it’s been three years.

I went over to do radio and TV and all that stuff for the Hard Act to Follow before it was on the air.

They had a big [to-]do at Palladium. It was so exciting.

They had Miles Davis, who was tremendous composer, musician, conductor.

He wrote a whole original score for |

Brownlow, not Brown. Carl Davis, not Miles. knew, of course, WHAT it was. |

|

Eleanor Keaton: On the other short...

I don’t remember what it was.

Could have been Cops or something.

But they had this young man, and he was a |

|

|

Marion Meade: Sounds wonderful. First of all, Raymond... The transfer —

|

|

|

Eleanor Keaton: Raymond was almost dead. He came that night. He had been —

|

|

|

Marion Meade: He really looked that —

|

|

|

Eleanor Keaton: I never saw him. He was hiding.

He came over from Paris to the Mayfair Hotel, and Kevin... David knew he was there.

He talked to David on the phone, because he wanted to see Hard Luck.

He’d never seen it put together.

He wanted to see his due.

At the last minute, just exactly on time as the lights were going down, David and Linda,

who did the research for Hard Luck, they saw him.

He sneaked in, and he had...

The Palladium does not have air conditioning.

It was quite warm in that theater.

He sneaked in with a heavy overcoat on, and sat in the back row and watched Hard Luck.

In the middle of the other short, they went and... David and Linda went and spoke to him.

In the middle of the second short, he got up and left,

because he didn’t want anybody to see.

He was down to about 95 pounds. [crosstalk 00:08:28].

|

|

|

Marion Meade: Well, it was his AIDS.

|

|

|

Eleanor Keaton: I’m sure it was AIDS. Nothing was ever said, but I’m positive.

|

|

|

Marion Meade: Probably. If he was wearing an overcoat in the summer, it sounds like AIDS, doesn’t it?

|

|

|

Eleanor Keaton: I’m positive it was AIDS. And he was down to 95 pounds.

He only lasted maybe two months after that.

He made it home to New York and tripped to his bed, and I don’t think he ever got up.

Nothing was ever said about what he died of, but I’m positive. I know it was AIDS.

|

|

|

Marion Meade: No, it wasn’t. Alan Twyman or Richard... I forget his —

|

Richard Gordon. |

|

Eleanor Keaton: I told Alan, I said, “I know it was AIDS.”

|

|

|

Marion Meade: He said, “Well, he wasn’t expecting to die.

That’s why his apartment is such a mess, because he didn’t make any preparations.”

But some people —

|

|

|

Eleanor Keaton: He may not have thought he was going to die, but everybody else did.

Who’s Richard? I didn’t know any of those —

|

|

|

Marion Meade: He’s a... He handles the foreign rights for Keaton Films.

He’s Alan Twyman’s... He distributes —

|

|

|

Eleanor Keaton: The counterpart.

|

|

|

Marion Meade: Yeah. Right. I forget his last name.

|

|

|

Eleanor Keaton: The only person... I get all my money through Alan.

|

|

|

Marion Meade: Right.

|

|

|

It is obvious that Eleanor never learned the details and got the story entirely muddled.

She also misremembered things, which was rather uncharacteristic.

|

|

A researcher just refuted much of my argument concerning Mason and Sheldon and Rohauer and Meade.

Please allow me a week or so to make corrections.

Stay tuned!

|

|

There is another version of the Mason/Keaton story:

|

|

Keith Scott, The Moose That Roared: The Story of Jay Ward, Bill Scott, a Flying Squirrel, and a Talking Moose

(NY: St. Martin’s Press, November 2001), pp. 226–227:

In 1954, while managing the Society of Cinema Arts in Los Ángeles,

Rohauer was contacted by actor James Mason, who had bought Buster Keaton’s

house. Mason had discovered a gold mine of valuable film stored in

the basement. This was Keaton’s personal collection....

|

|

You have now read how many different editions of this story?

They all contradict, and not in minor ways, but in essentials.

Each is incompatible with all the others.

Which one is right?

What really happened?

I don’t know.

I shall make a good, intelligent guess below, but I really don’t know.

Do you?

|

|

As you see, Jim Curtis had his own version of this story, except that he told more of the story than he realized.

He broke it into pieces, not realizing that the scattered pieces properly belonged together.

Altogether, this got my head to spinning.

It took me two weeks to make sense of two pages of Jim’s text,

and even after two weeks of trying to make sense of it, I have to toss up my hands in despair.

I’ll never get it right unless better sources happen along.

So, now, allow me to try my hand at the story.

I am certainly messing it up, but let me try anyway.

As we learn more, I can make corrections.

If I’m piecing the shards together correctly, this is what happened.

|

|

Natalie Talmadge sold the Italian Villa in Beverly Hills in 1932, and the property then went through several ownerships.

None of the owners was aware that the subterranean film vault was there, because it was entirely concealed.

Nobody could have guessed that there was a steel safe door with a dial lock hidden behind a false shelving wall in the gardening shed.

James Mason and his wife Pamela purchased the mansion in 1952 at a bargain-basement price.

How on earth James Mason or his wife or his children or his gardener or whoever noticed that safe door, heaven only knows.

My guess is that they did not find it and did not even suspect it was there — not yet, anyway.

|

|

A researcher just refuted much of my argument concerning Mason and Sheldon and Rohauer and Meade.

Please allow me a week or so to make corrections.

Stay tuned!

|

The Buster Keaton Story |

|

I don’t think that the James Mason story is a

|

|

So, let’s put the Masons and the villa aside for a few moments

and let’s take a look at somebody else in Southern California.

It was probably early in 1955 that screenwriter

Robert Smith

drafted a treatment for a screenplay about an abrasive circus clown

who somehow became a star in silent movies but was headed towards a drunkard’s grave until a virtuous woman rescued him.

Well, I think that’s what the basic plot was.

I cannot be sure until I find that treatment, if it still exists.

Robert Smith knew nothing whatsoever about cinema history and so he just made everything up in the most cornball fashion imaginable.

It seems, from what little I can recall of the movie,

that Smith at first wrote the story without a thought to any particular silent comic.

It was just a generic tale of a generic unfunnyman, a standard gimmick, nothing more.

|

|

Some or all of the drafts of the treatment and screenplay are on file at the Margaret Herrick Library.

I shall soon attempt to look at them, and, if permitted, I shall copy or transcribe them.

If I am not permitted, I shall at lease see if I am permitted to read them and take notes.

Those drafts should prove most enlightening.

|

|

My guess (a guess, a guess, nothing more than a guess) is that Robert Smith was unable to sell his treatment to any of the studios.

Then, in about June 1955,

Smith somehow got the idea to attach a real name to his clown.

What made him pick the name Buster Keaton we may never know.

Could it be that he had heard through the grapevine that something called the George Eastman Awards would be given out in November,

and that one of the recipients would be Buster Keaton?

Maybe. Maybe not.

He probably thought that studios might be more receptive to a script based on a real celebrity than one based on a fictional celebrity.

He asked some acquaintances if they knew anything about this Buster Keaton fellow.

My guess is that someone said, “Yeah, he was a kid in vaudeville, a star at four years of age, had an act with his parents called The Three Keatons.

He was a hit in silent pictures but became a drunk when sound came in.”

At that, Smith must have blurted out,

“That’s enough! Don’t tell me more. I’ve got it. Thanks!”

He would change his clown’s name.

His clown would now be named Buster Keaton.

How could he get a studio interested?

Simple, he could send out a press release implying that plans were already underway.

|

|

The above story is notable as much for what it does not say as for what it does.

It does not list Robert Smith’s previous production or direction credits, because he had none.

It establishes his credibility by mentioning two of his screenplays, neither of which had yet been filmed.

It states not that Smith will produce, but that he plans to produce.

It does not mention which studio is backing the production, because no studio was backing the production.

This news story was based on a press release that Smith mailed out from his home in the hopes of generating interest.

|

|

It would be a perfect vehicle, much easier to sell.

It would be about a real celebrity

and it would include scenes of self-pitying and maudlin scenes of drunkenness

and tug-at-your-heartstrings sentimentalism topped off with reform

and a baby-makes-three-they-lived-happily-ever-after ending.

Just what the doctor ordered!

The studios would be falling over each other to purchase that story.

To adapt it for Buster required only that a few words be changed here and there.

|

|

Smith met with Buster, who accepted a $1,000 option to allow a movie of his life story,

but Buster was quite sure that the movie would never happen.

It was just an easy grand, that’s all.

|

|

Smith, already receiving writer’s checks from Paramount,

would not produce the film nor would he direct it.

He did not have the qualifications even to approach a studio about producing or directing.

He needed someone to stand behind.

He approached young director Sidney Sheldon

(yes, that Sidney Sheldon).

The two had never met before, and Sheldon had never heard of Smith.

He had, though, been a Buster fan since he was a kid, and he enthusiastically agreed.

By August(?) 1955, Robert Smith and Sidney Sheldon were officially production partners.

They would write the script together and Sidney would direct.

Sidney was sure the script could be fixed once Buster was at hand, but in that assumption he was woefully mistaken.

Robert and Sidney met with Paramount, which agreed to purchase sufficient shares to get the project off the ground,

and Sidney then announced The Buster Keaton Story at the end of

August 1955.

|

|

It is probable that Smith had never seen even a single one of Buster’s movies.

That might explain his casting ideas.

He thought that George Gobel, a verbal comic, could portray Buster.

He also thought about Jerry Lewis.

If you think the movie as it stands is awful, imagine how much worse it would have been with Jerry Lewis.

That would have been prosecutable as a crime against humanity.

He also thought about

Donald O’Connor, a professional dancer.

Buster was okay with either George or Donald, but with a preference for Donald, who could do physical comedy.

Donald got the job, and, bless him, he threw a fit to change the script to replace the circus with vaudeville.

|

Robert Smith looks with proud satisfaction at the file copy of his script. Donald O’Connor silently looks over at Buster as if to say, “Well, what can I say?” Buster silently looks at Donald as if to say, “You’ve gotta be kiddin’ me.” |

|

Robert and Sidney now needed to watch some Buster movies in order to prepare their movie,

and they surely asked around for prints.

The only available films were MoMA’s 16mm circulating prints of

Sherlock Jr.,

The Navigator, and

The General.

Those prints were perpetually being shipped to various high schools and public libraries,

and chances of booking them on short order were slim, but they managed it!

They rented the 16mm circulating prints for all three of those movies.

I assume they chatted with the folks at MoMA,

and I assume further that the folks at MoMA said something like,

“By the way, if you can ever find more of Buster’s movies, please let us know.”

|

|

During discussions with Buster, Robert and Sidney surely asked if there were any more prints,

and perhaps Buster mentioned that he had left some behind at his villa.

Which films?

Buster probably rattled off a few titles and Robert and Sidney probably went wild.

They then probably contacted MoMA to say that, if they hadn’t yet turned to goo,

there might still be more Buster movies at the villa.

MoMA then phoned Buster to confirm this and pleaded with him to attempt to get them back.

Later on, Buster remembered that it was Sherlock Jr. that MoMA was especially keen for,

but Jim Curtis tends to think that Buster misrecalled.

|

|

That’s what prompted Buster’s visit to what was by then Mason’s property.

He drove to the villa in 1955, probably in September of that year.

He managed to get past the gate and it seems he got to the front door.

Mason was away, but his friend

Kenneth Tynan was there, and it was he who answered the door.

Buster had no idea who he was and assumed he was the butler.

Buster explained that he had left his films behind many years ago and was hoping he could collect them.

Kenneth Tynan must have been a bit dumbfounded.

He went back inside the house, asked around to see if anybody knew what in the blazes Buster was talking about,

returned to the door, and demanded an explanation.

Buster revealed the secret:

Inside the gardening shed there was a shelving wall, but it was a false wall.

Behind that false wall there was a safe door with a dial lock, and no, sorry, he couldn’t remember the combination.

Behind the safe door was the concrete bunker where he used to edit his films.

Kenneth Tynan must have been stunned by this news.

He must have promised to convey Buster’s information to Mr. and Mrs. Mason, upon which he sent Buster away.

|

|

A researcher just refuted much of my argument concerning Mason and Sheldon and Rohauer and Meade.

Please allow me a week or so to make corrections.

Stay tuned!

|

|

The Masons must have been even more stunned than Kenneth.

They immediately hired some workmen to excavate for the vault.

The workmen were able to locate and open the false wall, behind which they discovered the safe door.

Mason ordered them to

drill it open.

Inside, yes, were cans of film, much of it rotted, either piles of goo or crystallized into hockey pucks or disintegrated to dust.

(Please click through this slide show

to see what happens to film as it ages.

That doesn’t sound too exciting, does it?

Well, it is pretty exciting. Take a look.

Take a look at the little documentary below, too.)

|

|

Insider, How Old Movies Are Professionally Restored | Movies Insider, posted on Feb 17, 2022 When YouTube disappears this video, download it. |

|

Mason contacted the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences and promised to donate the materials

once his accountant completed an assessment on the value of the collection for tax purposes.

Mason had a servant contact Buster to tell him that, yes, some films were indeed inside,

but that the Masons would absolutely not return them, as they had made arrangements to donate them to the Academy.

Buster responded that, in fact, it was the Museum of Modern Art that had requested the films.

James Mason agreed to get the cans of at least one of the films to MoMA

(Curtis has documentation that suggests it was Our Hospitality),

but with the stipulation that when MoMA was done, it would transfer the print to the Academy.

Buster, James, the Academy, and MoMA all agreed with that plan.

|

|

At no time did Buster and James Mason ever talk directly,

at least not at this stage of the story.

They may have met later, as Ray Rohauer claimed.

In the meantime, everything they said to each other was through intermediaries.

|

|

I have absolutely no evidence that my reconstruction of events is accurate; so please do not take it as confirmed fact.

I am not Dardis. I am not Meade.

I do not proffer my conjectures as truth.

I am trying out various guesses to see what would fit the known evidence, and, so far, this fits, but that doesn’t make it real.

I am practicing “exploratory conjecture,” which is a lot of fun but which is also littered with landmines.

If you put my conjecture into a book and state it as confirmed, I’ll punch you on the nose.

|

|

We need to take into account a contradiction.

Let us briefly review two newspaper articles

(Jim Curtis, pages 576–577):

|

|

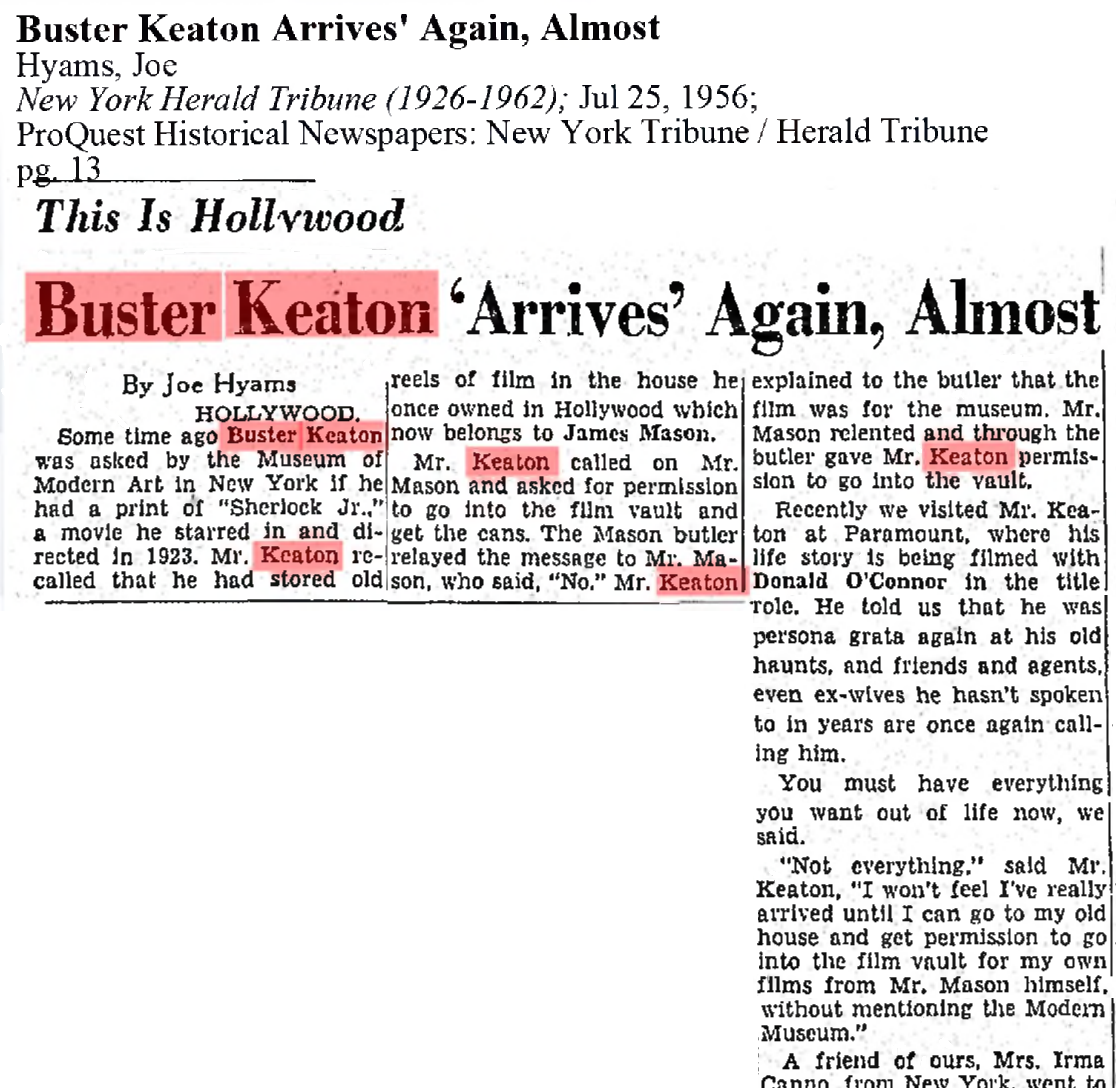

Keaton spoke on the record about it twice. In an interview with Joe

Hyams of the New York Herald-Tribune, he said he had been asked by the

Museum of Modern Art if he had a print of Sherlock Jr. According to

Hyams, Keaton called at the house and requested permission to go into

the vault and retrieve the cans. The Mason’ butler relayed the message and

the answer came back: “No.” Keaton explained to the butler that it was

for the museum, and thereupon Mason relented. With plans for The Buster

Keaton Story going forward, Hyams suggested that Keaton must now have

“everything he wanted” out of life.

“Not everything,” Buster returned. “I won’t feel I’ve really arrived until

I can go to my old house and get permission to go into the film vault for

my own films from Mr. Mason himself, without mentioning the Modern

Museum.”

Two months later, Keaton told much the same story to Jim Cook of the

New York Post, and this time he was quoted directly: “He sold off most of

the ten [ten] acres, and the crowning indignity came when I went to the

house... to get one of my old films which was still in the vault there.

Mason wouldn’t come to the door and the maid said I couldn’t get the film.

But I played a trump card — I told her to tell Mason that the Museum of

Modern Art in New York wanted it. I got it then.”

|

|

Now you see why I cannot make this story out in a satisfactory way.

Kenneth Tynan first becomes the butler and then he becomes the maid.

“Crowning indignity” was not part of Buster’s spoken vocabulary.

“I got it then”? He did?

Then how did it end up at the Academy just afterwards,

with Buster needing to make a written request to borrow it?

|

|

A researcher just refuted much of my argument concerning Mason and Sheldon and Rohauer and Meade.

Please allow me a week or so to make corrections.

Stay tuned!

|

|

Jim Curtis (pp. 575–578) explains that the abandoned editing bunker contained only seven short films.

According to Matthew Bilodeau,

“Buster Keaton Had to Do Some Digging to Rescue His Early Films,”

/Film, 3 September 2022, the seven shorts were

The Playhouse,

The Boat,

The Paleface,

Cops,

My Wife’s Relations,

The Blacksmith (early preview print), and

The Balloonatic.

As for the feature films, Curtis explains that only

Battling Butler,

The General (final preview print),

College, and

Steamboat Bill, Jr.,

were complete and usable.

Our Hospitality,

Sherlock Jr., and

The Navigator had partly disintegrated.

Three Ages,

Go West, and

Seven Chances had completely disintegrated.

There was one further film there, too, a dreary MGM flick called

Parlor, Bedroom and Bath, a few scenes of which had been filmed on the villa grounds.

|

|

As far as I know, Buster and Natalie moved into the Italian Villa at the end of 1926,

and so the only films he would have edited in that secret bunker were

College and Steamboat Bill, Jr.

The previous films he had edited, I suppose, in the studio.

|

|

In January 1956,

Mason donated the prints to the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences, except for Our Hospitality,

which was presumably on loan to MoMA.

Because parts of Our Hospitality had decayed so hopelessly,

there was no way for MoMA to do much with it,

and so MoMA quickly donated Buster’s print of Our Hospitality to the Academy as well.

That is how, at the beginning of 1956, the Academy acquired the totality of the known Buster Keaton collection.

Except — that it was not the totality of the known Buster Keaton collection.

|

|

This is where we need to pause this narrative to delve into another.

Hold tight. This will be a rough ride.

|