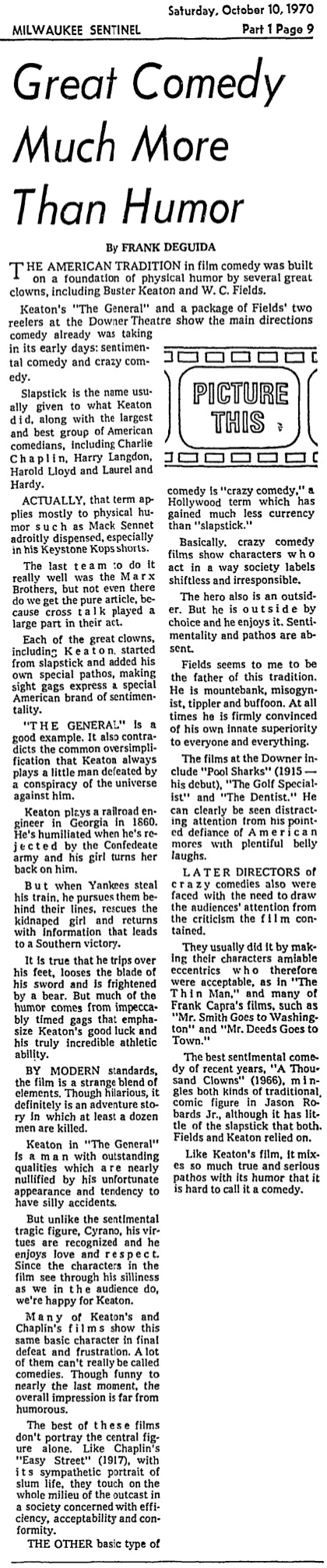

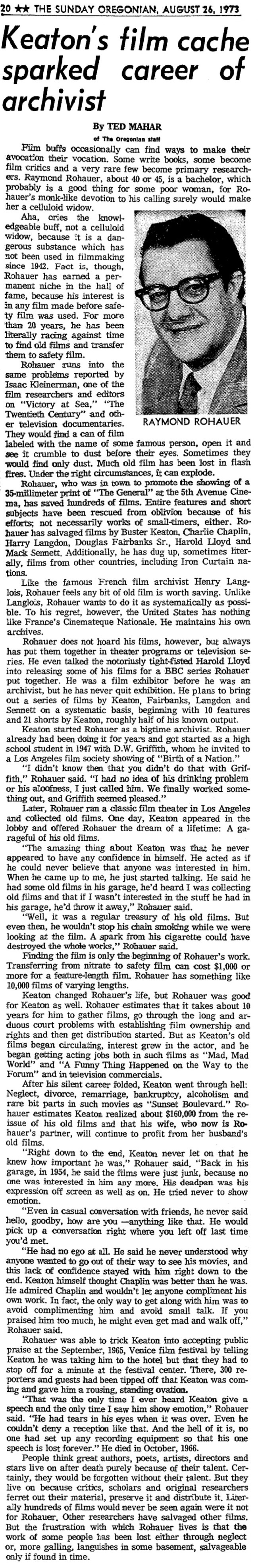

The Buster Keaton Film Festival |

|

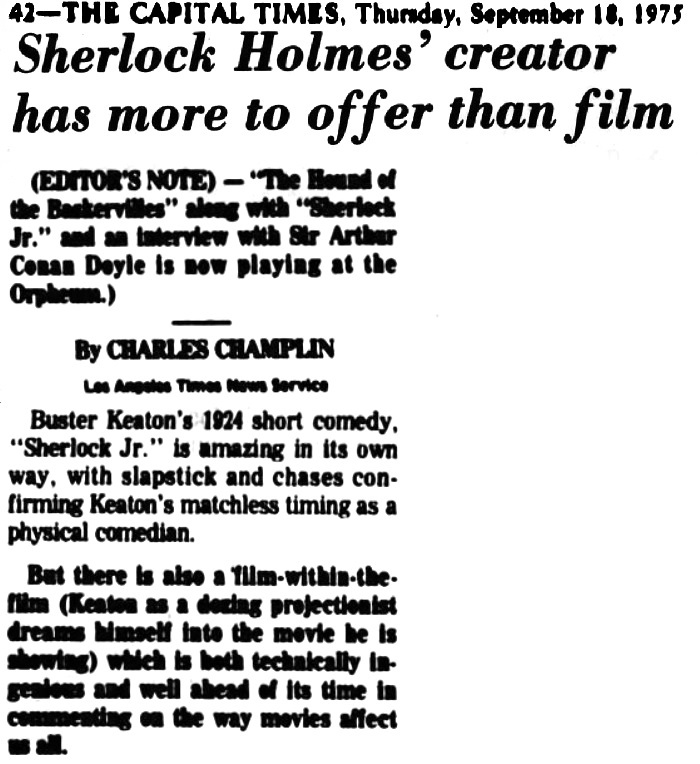

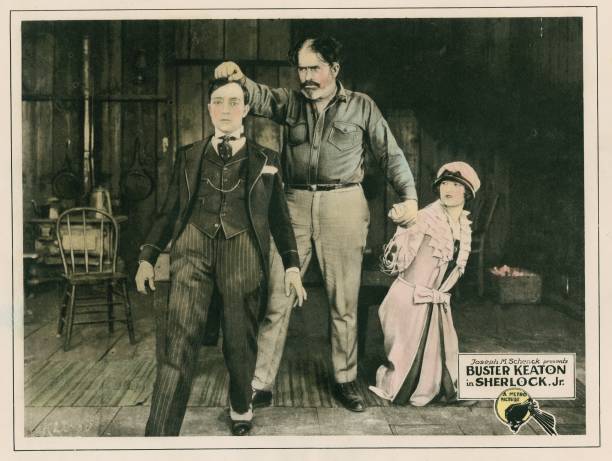

In September 1969, the Surf received the BUSTER KEATON retrospective at rallying point Ku Riba, but with extras:

|

|

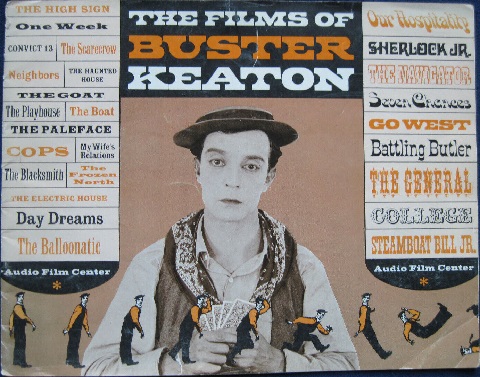

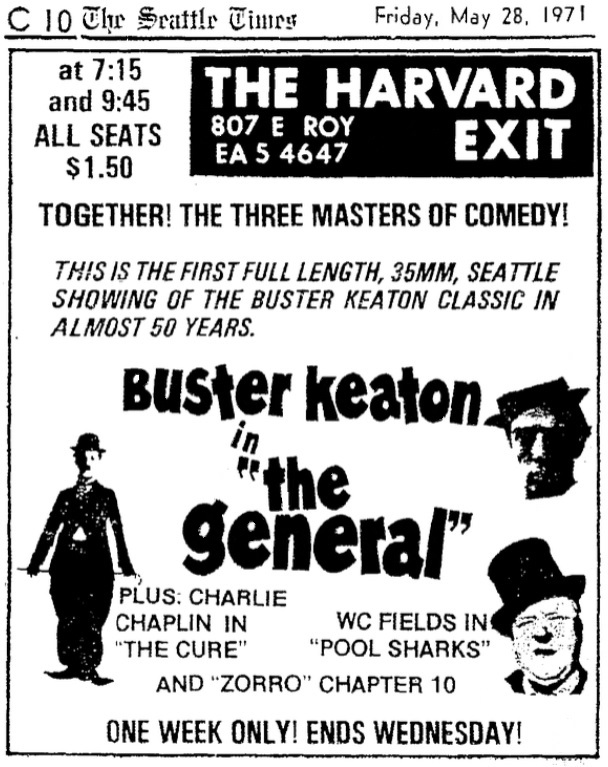

Never knew about this until a Paul Richards shared this advertisement

with the Buster Keaton Reddit group (Thursday, 30 March 2023):

|

|

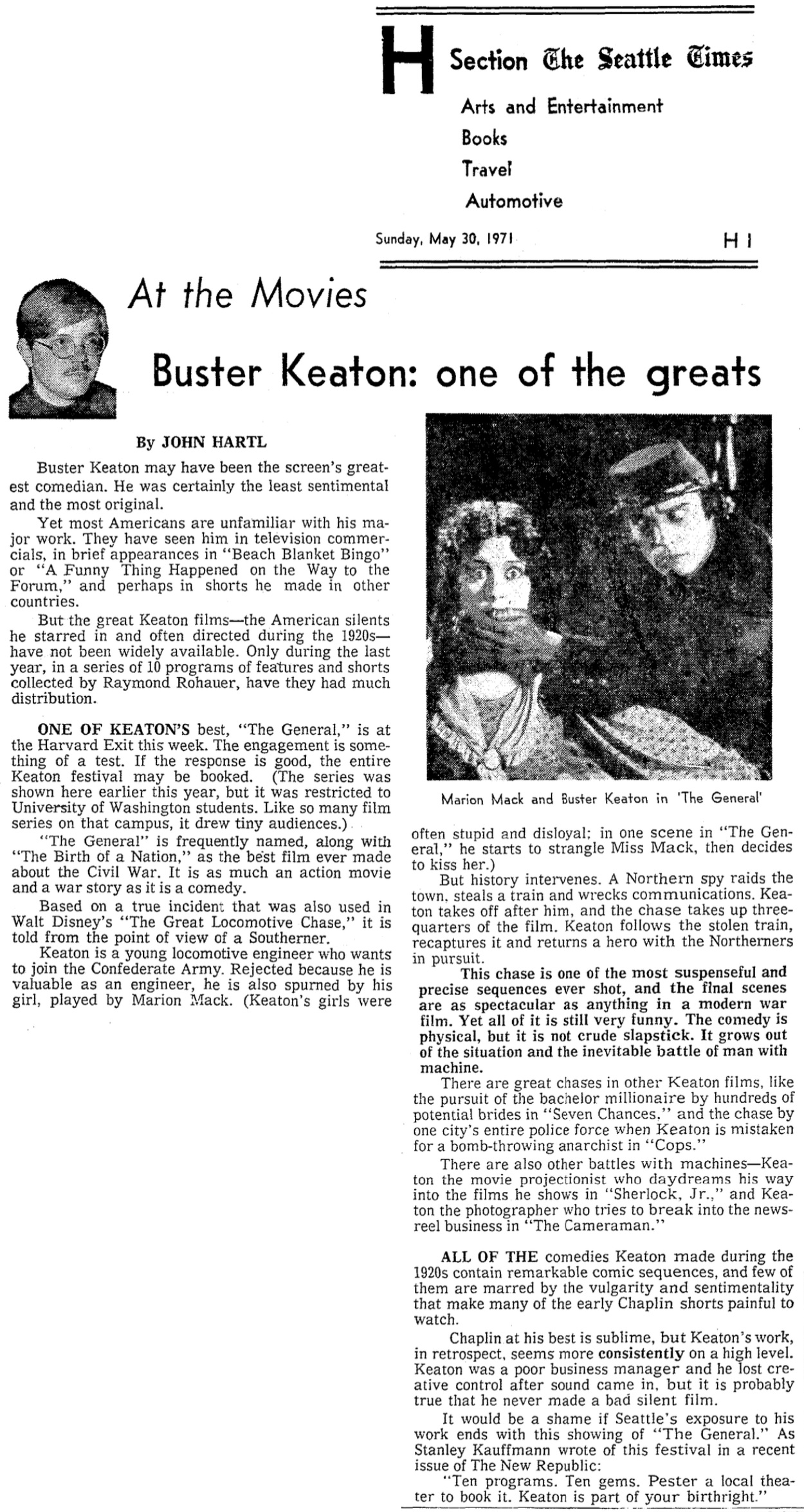

Ray then moved the retrospective to NYC on Tuesday, 22 September 1970,

when he began a five-week “Buster Keaton Film Festival” at the

Elgin Theatre.

The prints, I presume, were full-aperture silent, and

a piano player accompanied.

I can only assume (and hope!) that Ray’s people loaned the Elgin the proper gear to show the films.

This was the first time since the original releases that most of these films had been seen in NYC.

While Rohauer was showing his silent print of The General at this NYC festival,

the Jay Ward “sound version” was premièring at cinemas elsewhere.

Hold that thought.

|

|

Just after the “Buster Keaton Film Festival” finished at the Elgin,

Ray was invited to appear on “Camera Three” to spout a bunch of lies:

|

Image stolen from eBay.

Once upon a time, I had Rohauer’s beautiful Keaton catalogue.

I think I found it lying around a theatre where I was employed.

Nobody wanted it, and so the house tech invited me to keep it for myself.

I think that’s what happened.

I hope I still have it in my storage locker. Hope so.

I did not realize at that time, nor did I realize until I was scribbling this essay,

that nearly all those films had been entirely unavailable for more than four decades

at the time the catalogue was issued.

Generations had grown up knowing nothing of this output, and when people saw these Festivals, they were wowed.

Now, at long last, I finally understand the origin of those endless Chaplin-v.-Keaton debates that got people so inflamed.

Buster’s and Charlie’s better movies had been almost entirely unavailable since they were new.

Unexpectedly, in January 1968 in London and in September 1970 in NYC,

people saw Buster’s finest works for the very first time.

Chaplin then began reissuing his movies in December 1971.

For the forty or so years prior to that time,

pretty much all that had been available was just a handful of his earliest primitive shorts,

butchered and battered to unwatchability.

People saw his finest works for the very first time beginning in December 1971 and were wowed.

Belligerents in pubs immediately lined up to take sides and get into brawls.

Humans. I’ve never understood humans.

|

|

So many fibs in the interviews above. So many, many fibs.

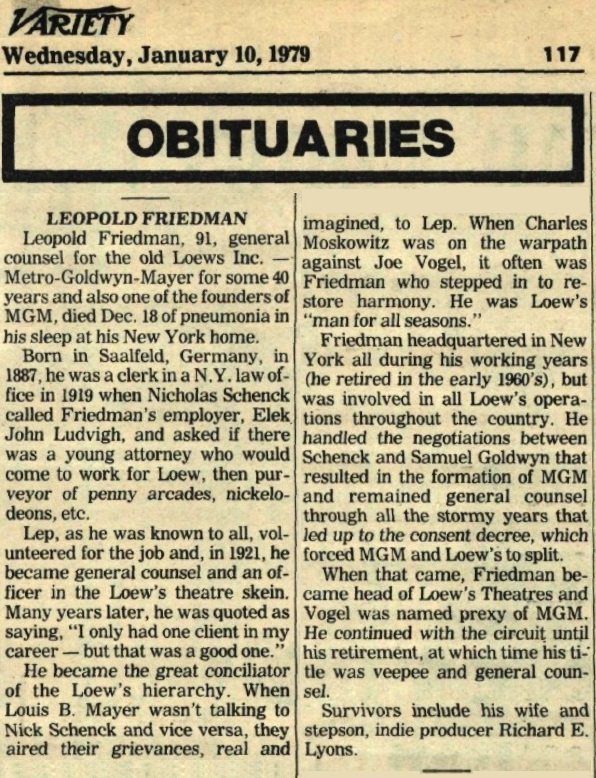

Buster had few or no scars. Ray Rohauer did not meet Buster in 1954, but in August or September 1958.

Buster did not have “a garage full of junk.”

He had no copies of any of his films, and so he did not threaten to toss them out.

The prints at the Surf were not “irreplaceable,” since each was derived

either from a new duplicate negative or from a new copy negative.

(Oddly, some of those prints and negatives have since that time gone missing and were replaced by inferior materials.

Why and how remain a mystery to me.

That is why a few brief shots from several films that people saw at the Elgin in 1970 are no longer available anywhere.)

I have my doubts about Ray’s story of finding negatives and possibly other materials at MGM,

and I really have my doubts about finding the “original” negative of The General at MGM.

It’s not out of the realm of possibility.

After all, MGM did once have an option to remake The General but allowed that option to expire.

It is possible that MGM was loaned the negative at that time and then never returned it.

Still, though, I have my serious doubts.

By 1965, Buster was keenly aware that people really did care about his films.

The implication that the Surf already had the proper Silent aperture plates (and therefore lenses and masking) is most heartening.

I wonder if the Surf had speed controls as well.

Jack Tillmany’s Gateway was properly set up for Silent,

but I thought that was the only one in San Francisco that could handle silents in those days.

I’m glad to know I was wrong.

|

|

You noticed above the link to a little thingy called

The Metaphysics of Buster Keaton.

That little program answered a question that had been gnawing away at me for half a century:

Was Rohauer’s touring festival print of The General

|

|

This full “Buster Keaton Festival” package went back to the

Surf in San Francisco to run through snow with Kasumi in

December 1970,

again probably full-aperture silent

and probably with piano accompaniment.

The package returned to the Elgin in

March 1971.

Part of this package went to Sir George Williams University in Montréal in the

spring of 1971

and the full package was shown there in September of that year.

The package went to Los Feliz in Los Ángeles in

May 1971. In

July 1971, the package went to the Saratoga Performing Arts Center in Saratoga Springs, NY.

Then to the TLA Cinema in Philadelphia, PA, in

September 1971,

back to NYC at the

Olympia beginning on

23 December 1971,

then the Verdi in Montréal in

January 1972,

then the Hull Film Theatre in Kingston-upon-Hull from

March through May 1972,

then the Manchester Film Theatre in

October 1972,

then the Arts Lab Cinema Club in Birmingham in

April 1973,

then as part of the Atlanta Film Festival in

September 1974,

much later to the

Orson Welles Cinema in Cambridge, Massachusetts, from

28 September through 1 November 1977,

then a bunch (probably release prints rather than festival prints) popped up at the

Vagabond in Los Ángeles in

July 1979,

and then oh heck I lose track.

|

Killiam Shows

|

|

By 1969, Rohauer was doing well by exhibiting his Buster collection.

So, Killiam decided to compete.

Besides, he had surely heard that Jay Ward had a reissue in the works,

and he did not want it to take over his market.

He reached into the cans of trims and attempted to reconstitute The General, but there was a problem:

He could not remember how the original was pieced together.

So, he guessed, and his almost every guess was wrong.

|

|

No. No. No. No. No no no no no no no no no.

That’s not what happened.

Shall I try again?

|

|

By 1969, Rohauer was doing well by exhibiting his Buster collection.

So, Killiam decided to compete.

Besides, he had surely heard that Jay Ward had a reissue in the works,

and he did not want it to take over his market.

He ordered a staffer to reach into the cans of trims and attempt to reconstitute The General, but there was a problem:

The staffer had no idea at all how the original was pieced together.

He had never seen the film in any version,

and this mess was a massive jigsaw puzzle that he needed

to piece together in the dark — while blindfolded.

So, the staffer guessed, and his almost every guess was wrong.

|

|

That second attempt sounds much more realistic, doesn’t it?

|

|

The staffer did the best he could and finally submitted his faulty work,

even though he knew that there were sequences he had never spliced back in.

He showed his work to Paul, who saw nothing wrong with it and released it.

|

|

If that’s not exactly what happened, it’s almost exactly what happened.

|

|

Almost nobody ever noticed.

Except for me.

When I look at the Killiam edition of the film,

I see nothing but disaster after disaster after disaster,

with more shots and sequences out of order than I could possibly count,

and with the narrative shot to senselessness thereby, made worse by the omissions.

|

|

The staffer mostly got the scenes in order, but the shots within the scenes were scrambled.

He cut shots in two and placed them in the wrong contexts.

Many shots had been trimmed by only a second or two for the abridgments,

and it just wasn’t worth the bother to patch those back together again.

The result is that many shots are noticeably shorter than they are in the authentic edition.

As for the first shot of Johnnie sitting on the connecting rod (the first shot of Reel 2),

it looked like duplicated action and so the staffer left it out.

Annabelle boarding the train? All the shots were out of order and one of them was split in two.

The second shot of the fireman, the conductor, the station master, and the baggage handler

watching Johnnie running off after his train?

Gone.

As for the reverse shot of Johnnie pumping the handcar, again,

the staffer didn’t see where it belonged and so he left it out.

A cutaway to the Raiders? He didn’t know that it began Reel 3, and so he stuck it in the midst of Reel 2.

Johnnie breaking his axe handle while he chops wood?

Gone.

Johnnie clubbing the sentry posted outside the door? Gone.

Johnnie and Annabelle waking up in the woods? Nearly all the shots were out of sequence.

Startlingly, he had Johnnie rescue Annabelle from the boxcar BEFORE he had Johnnie break the telegraph wires,

and that made utter nonsense of the continuity.

The staffer must have spent weeks trying to work out what belonged where.

He could have cut the work down to a single day or less by the simplest expedient of borrowing a 16mm print.

He probably did not know that there were any other available prints.

|

|

The one bit of damage in the original was the 22-frame gap in Reel 5.

What to do about that?

Paul was happy to have damage in his copy of the movie.

Happy? Nay, eager!

But the damage in the Killiam edition had to be DIFFERENT from the damage in any other copy anywhere else in the world.

What to do?

Ah!

A cinch!

Just delete the beginning of the shot and pick it up at the end of the gap!

So easy. So delightfully easy. And it works so well.

Nobody, but nobody would ever notice.

Until I came along.

|

|

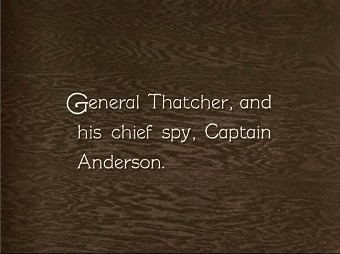

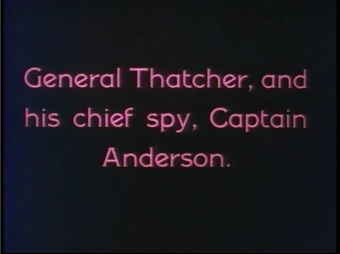

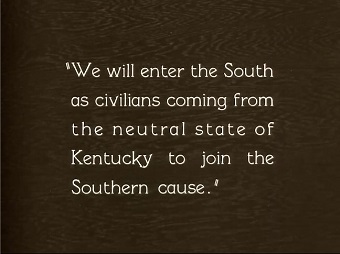

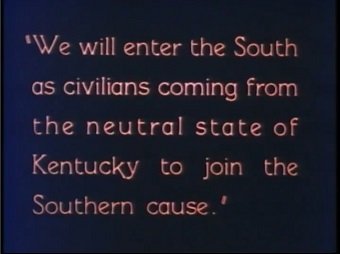

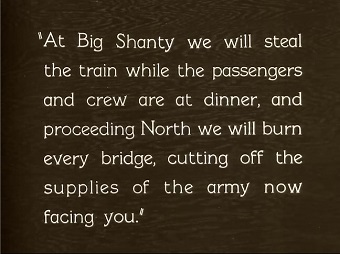

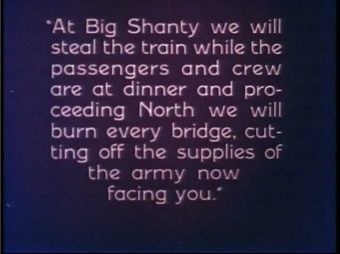

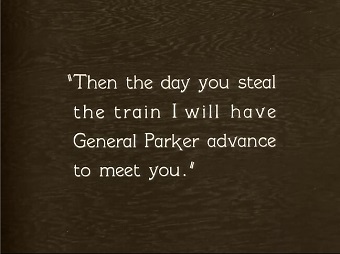

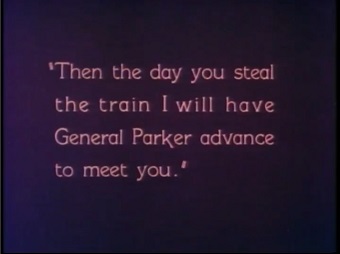

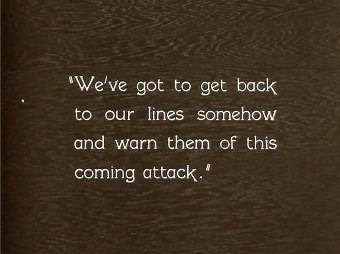

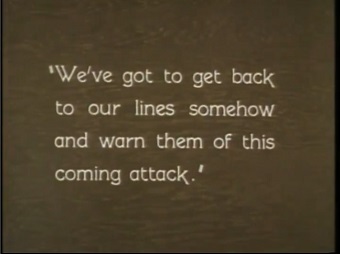

In the process of making all the other alterations, Killiam Shows also reshot some titles.

Not all, just some.

The font was almost the same, but there was no

|

| AUTHENTIC | KILLIAM |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| AUTHENTIC | KILLIAM |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

The above alterations are just small samples.

The alterations occur throughout the film, from beginning to end.

|

|

We need to ask ourselves Why?

Why did a staff editor get so much wrong?

Partly because there was nothing to check the work against,

but even so, some of the reconstruction should have been obvious.

Yet we need to take into account Buster’s filming techniques,

which were a byproduct of his editing technique, which was his alone,

it was a technique that, in those years, nobody else exercised, as far as I can tell.

|

|

A typical filmmaker making a typical film shoots scene 1 a couple of times until it is right,

and orders the preferred take to be printed and the rejected takes to be discarded without review.

Then it’s on to scene 2, ditto.

Then scene 3, and so on.

Each day, the editor works on the preliminary assembly by simply trimming the heads and tails off of the scenes and gluing them together.

Each day, the editor adds the previous day’s scenes to the growing assembly,

and then, a day after filming is completed, the preliminary assembly is ready for review.

There will be a few further trimmings or intercuts, and then the movie is done.

Simple.

|

|

Buster didn’t do it that way.

He did not just have one scene follow the next only to progress the plot.

He wanted sinuosity, intercutting not so much to show two simultaneous actions, but intertwining emotions.

That is why he added brief shots that a typical editor would have tossed out as redundant or meaningless.

A good example is in Our Hospitality, when, in the midst of dramatic action outdoors,

we see a brief glimpse of Mr. Canfield pacing in his parlor.

That adds nothing to the plot.

It adds nothing to the action.

It tells us nothing about the story.

That brief moment serves another purpose, and that is to show an evolving emotion,

which is not connected with the action but which comments upon it.

That is what we call subtext,

a concept that too many editors find incomprehensible.

A typical filmmaker would never show us such an image.

A typical editor would toss that image into the rubbish bin as meaningless waste.

For Buster, such images were crucial.

Another, of somewhat less significance, occurs in Sherlock Jr.,

when we see Ruth Holly smiling out the candy shop’s window.

That image is not connected to anything in the story;

it simply adds texture, flavor, mood, atmosphere;

it establishes a feeling, it shows us that another character, of whom we catch only a few glimpses, has her own story,

a story we shall never learn, just as we never learn the stories of most people we ever see.

A typical filmmaker would never think to create such an image,

and a typical editor would never use such an image, but would toss it out as meaningless.

The General has such moments,

such as the first shot in Reel 2, which simply shows Johnnie sitting on the coupling rod,

a beautiful diagonal composition, much more evocative than the standard

|

|

Where did Buster learn this technique?

As I say, I am absolutely CONVINCED that, upon getting a contract to make feature films,

he studied the art of narrative, either from books on the subject or, more likely, from one or more instructors.

He probably attended lectures on the topic.

When he learned that novels have interior dialogue, he decided to invent a visual equivalent.

That, above all else, accounts for the monumental leap forward from Three Ages to Our Hospitality.

|

|

It is hardly surprising that an editor, confronted with over 7,000 feet of disassembled film fragments,

would not know how to piece Humpty Dumpty back together again,

especially a Humpty Dumpty as subtly complex as a Buster Keaton feature.

|

|

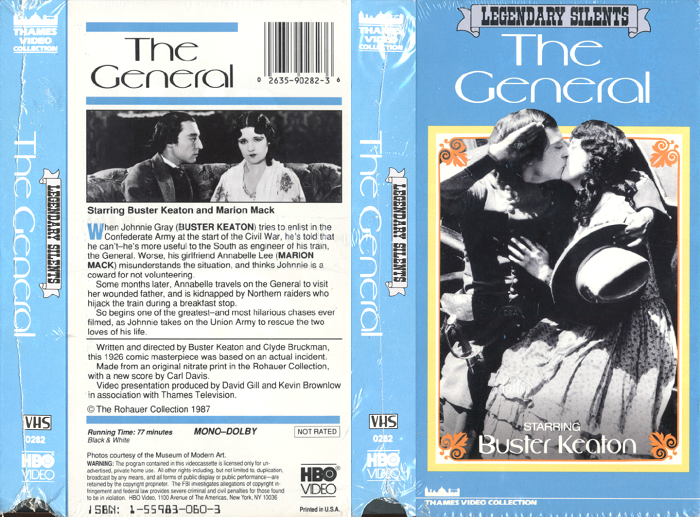

Paul licensed his collection to

Blackhawk Films of Davenport, Iowa, for home use only.

In July 1970, Blackhawk issued Killiam’s three editions of The General in 8mm, Super 8, and 16mm.

There was the 49-minute “Hour of Silents” edition, which had a soundtrack.

It could no longer be printed from the copy negative, because

the copy negative by now had been chopped and chopped again and recut and then filled out again and discombobulated.

So “Hour of Silents” was printed from a dupe.

As for the 25-minute “Silents Please” edition, the contracts for the narration

created for the TV series and later for The Great Chase

probably did not cover sales for home use, or, perhaps, the license had expired altogether.

The spoken commentary was here inserted as new title cards in a version that was strictly mute.

There was also the full feature, which was issued strictly silent,

surely because Paul Killiam had not yet contracted for a music score.

My guess is that Blackhawk was interested only in the fullest edition,

but that Paul insisted “all three or nothing.”

Just a guess. I don’t know.

|

|

This was the very first time that Paul’s feature-length edition of The General was seen by the public.

Casual viewers surely noted some horrendously awkward editing,

but, unfamiliar with the authentic film, they would not be able to assign blame,

and they quite possibly thought the film was like that from its 1926 release.

It was so frustrating, disheartening, demoralizing to spend good money for the Blackhawk-Killiam edition

and then to see Anobile’s photonovel of the Rohauer edition.

There was simply no comparison.

The Rohauer edition had poor contrast, but otherwise it was far better,

with greater sharpness, and it was noticeably more complete.

It was even more disheartening then to see the slightly trimmed Jay Ward edition at the cinema,

with its almost dazzling visual quality and with more material than Killiam would ever offer.

|

|

(By the way, the commemorative film, Return of the General,

is online. Just click the link.

The original film from which it was adapted,

Here Comes the General, produced by the Louisville & Nashville Railroad,

well, sorry, no idea where to find it. Does it still exist?)

|

|

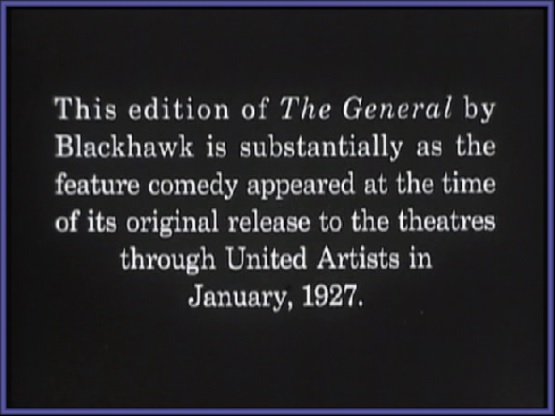

Those of you who have seen Blackhawk Films prints know all too well that each film began with a written historical introduction.

Why?

For use in schools.

When I was a teenager, these irritated me.

They would have been fine as printed handouts,

but I didn’t want my screen experience to be interrupted by these intrusions.

I feel a bit differently now.

The introduction to The General was authored by none other than Paul Killiam himself.

Let us take a look:

|

|

|

You will notice that this text is pretty much the same text used in the Blackhawk Films Bulletin.

It was also pretty much the same text that was printed on the later VHS and Beta covers.

The bit about the leading ladies being dumb, that was from Joe Franklin’s Classics of the Silent Screen,

which was one of the few statements in that book with which I completely disagree.

|

|

Daniel Moews, “Bibliographical and Filmographical Comments,”

Keaton: The Silent Features Close Up

(Berkeley, Los Ángeles, London: University of California Press, 1977), pp. 328–330:

The General is another film in which I have noticed differences

among available prints, enough differences, I suspect, to make a

collation of the prints a highly desirable project. In particular, my

impression is that the Blackhawk Films print, which is probably the

most widely purchased, is edited a little more tightly than most

others and is perhaps as much as a few minutes shorter. Again to

limit comments to places where my memory is certain, I can point

out two deletions in the Blackhawk version.

First, there is the joke of Johnnie’s handcart travels. In the Blackhawk

print, he starts his forward roll, there is then a shot of the

Union train passing the Kingston station, and in the next shot

Johnnie and his handcart reach the missing section of rail and go off

the track. In some other prints, there is an additional shot: Johnnie

starts his forward roll, Johnnie is shown from a side view moving

down the track, and only then is there the shot of the Union train

passing the Kingston station.

Second, when Johnnie escapes from northern headquarters, in the

Blackhawk print he is shown crawling toward the outside door with a

small log in his hand, obviously aiming to attack the sentry there.

There is then a cut to Annabelle in her bedroom, and this is followed

by a shot of a second sentry by a window, who is approached and

knocked out by Johnnie, now dressed in the first sentry’s uniform. In

other prints, there is also a shot of Johnnie reaching through the door

and clubbing the first sentry.

In both these instances, though I wish I knew who made the deletions

and when, the Blackhawk print seems to me better than the

longer versions. The handcart gag is made more emphatic. There is

no unnecessary filler movement between the start and the almost

instantaneous end of Johnnie’s handcart journey. Similarly, the

implied rather than shown clubbing of the first sentry seems to me to

improve the escape episode. It increases the comic surprise with

which Johnnie appears in Union uniform beside the second sentry.

Also, the fact that the audience was denied the sight of the first blow,

which it had been expecting, makes all the greater its gratification at

being allowed to see the second blow, the unexpected and comic

swing of Johnnie’s shouldered rifle. Although both cuts seem to me

good ones, if they were not approved by Keaton (as I assume they

were not), I would prefer that they had not been made.

There is, finally, evidence of another deletion, one present in all

prints of The General. The music cue sheet originally released with

the film contains one action cue to a shot not now there. Cut 19,

“JOHNNIE SNEAKS INTO HOUSE,” refers to his entry into northern

headquarters; cue 21, a title cue, “IT WAS SO BRAVE OF YOU,” is

spoken by Annabelle after she and Johnnie have escaped into the

woods. In between, however, there is action cue 20, “OFFICERS

LEAVE TRAIN,” and this shot is missing in all currently available

prints. Since it is an interruptive and unnecessary one, it might have

been removed long ago, perhaps even as a result of some last-minute

editing at the time of the film’s original release.

My real complaint, I suppose, in this minute brooding over the

possible completeness and authenticity of currently available prints,

is that films cannot be preserved and studied as easily as books, that

all editions from the first to the most recent are not available to the

different audiences who might be interested in them. Also, I worry

that no record of any sort may even be kept, that eventually, with a

film like Sherlock Junior, only

As a last note on the state of present-day prints, it should be added

that since The General is a film available in many

|

|

In 1977, that was the extent of our knowledge.

Nearly half a century has rasped by us in the meantime,

and so now we can answer the questions.

It was an editor on Killiam’s crew who made the changes to The General in 1970,

and the changes were far more extensive than mere shortening.

The missing cue, “Officers leave train,” is a typo.

It should be “Officers leave table,” and that cue is still there.

What Moews thought was a

|

|

Incidentally, it was not only The General that Killiam altered.

In 1970 he claimed a copyright on a new version of Chaplin’s 1925 film, The Gold Rush,

which was a strange composite.

It went back and forth, every shot or two, from a copy of the MoMA print

to a copy of the 1942 reissue,

back and forth and back and forth,

and the whole was abridged by several minutes.

What other changes his editor made, I do not know.

Someday I’ll examine it side by side with the other versions

so that I can see for myself precisely what he and his crew did.

I suppose that all the Killiam releases suffered these sorts of revisions.

|

|

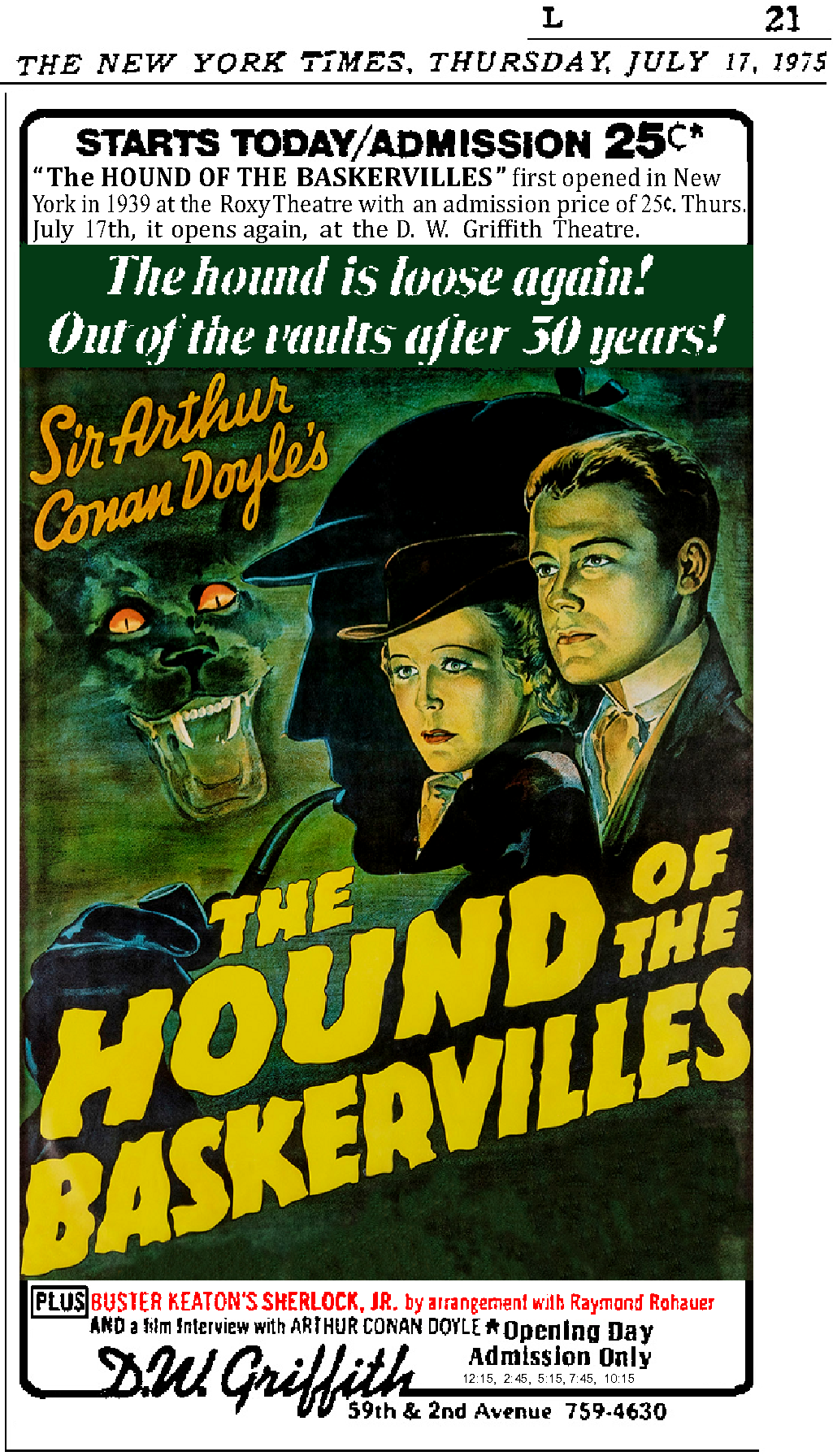

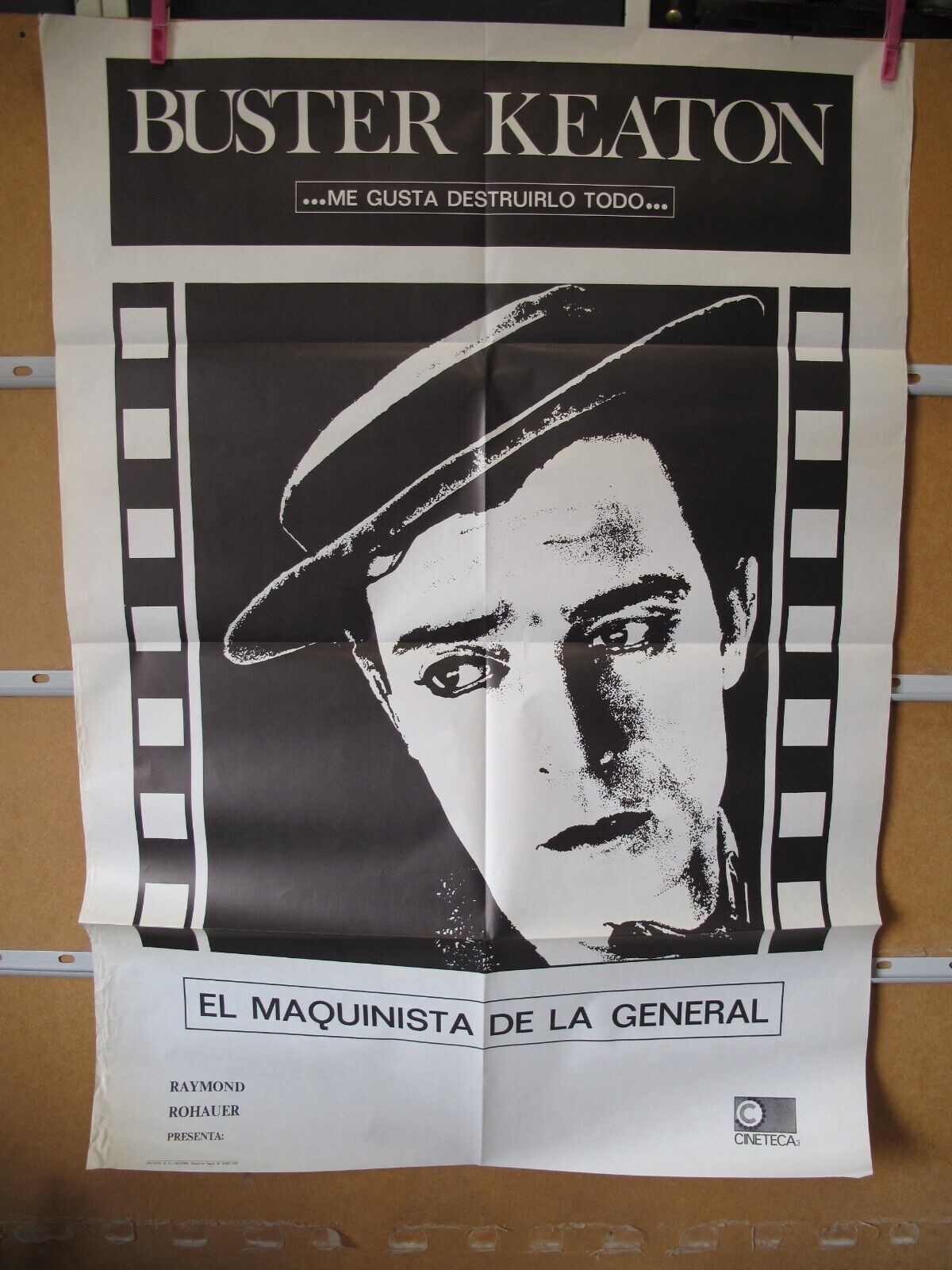

Here’s a poster for the follow-up series in 1975:

|

|

Then, in 1971, Paul began a new TV series on educational television.

It was first broadcast in NYC on the NET/PBS outlet WNET Channel 13.

It was called “The Silent Years,” hosted at first by Orson Welles,

later by Lillian Gish, and it ran through 1975.

This series was different from the previous two, for this one played the full-length films.

Paul hired

Karl Malkames

to film the intros and outros and to perform the restoration work preparatory to broadcast.

I can only assume that this restoration work consisted primarily of tinting the movies.

The broadcast editions did not match the tints of the original releases.

Malkames just tinted the films any old which way he wanted to.

He could not utilize the original obsolete and unavailable technology,

but instead used color filters on color stock.

The scores were by William P. Perry, who accompanied on piano.

(He wrote a sweet score for The General.

Unfortunately, it was miked poorly or

maybe some settings were off,

and so the sound of the piano was too harsh.

If you are an audio engineer, can you fix that?

If you can fix that, could you? And send me a copy? Pretty please with sugar and honey on it?

When I hear the Annabelle Lee waltz,

over the music my mind superimposes the words, “After the day is over, oh my dear Annabelle Lee...,”

and then my imagination crashes to a stop and no more words come.

You can listen to an interview with Bill Perry

here and

here.)

This newly tinted/scored edition of The General premièred on WNET Channel 13 in NYC on Tuesday, 3 August 1971.

The film was in the public domain, and yet it claimed a copyright.

(I have not been able to find a copyright registration.)

When Paul reconstituted the film from the cans of trims from the copy negative,

he got everything wrong, and thus he inadvertently created a new version of the movie.

Indeed, the credit reads, “COPYRIGHT 1926 BY JOSEPH M. SCHENCK. THIS VERSION COPYRIGHT 1970 BY KILLIAM SHOWS, INC.,”

which was misprinted as Killiams Shows in some prints.

|

|

“The Silent Years” broadcast the film from a 16mm print that had been reformatted.

The center of the image was enlarged and all four edges were trimmed off, noticeably.

|

|

If you want to see the Blackhawk edition with the Blackhawk intro, mostly but not entirely accompanied by the Bill Perry score,

it’s available on

|

|

When did Paul release 35mm full-aperture silent (.723"×.980") prints of this film to cinemas?

Not in 1957. Not in 1960.

I know for certain that it was in distribution by 1978 (which is when

it played at Don Pancho’s in Albuquerque).

It may have been as early as July 1970 that Killiam issued the movie to cinemas, but I doubt it.

I bet he issued it to cinemas in September 1971.

That would have been right after the showing on WNET/13, which would have served as his promotion.

|

|

Because it is Albuquerque, and because it was The Guild, a hole-in-the-wall dump that I adored

but which absolutely loathed me in return, I feel it only right and just to show you the following newspaper advertisement:

|

|

I had wondered which edition this was.

Was it Rohauer’s edition? Jay Ward’s? Or Killiam’s?

The advertisement is rather vague.

How was I to interpret it?

Well, let’s think this through.

The Guild ran only 35mm in them days.

There were only three distributors offering 35mm prints of The General in early 1972:

Rohauer distributed his own

|

|

Like I keep saying, it was a bit odd to issue a full-aperture silent print,

since, in those years, there were literally only three or four commercial cinemas worldwide that could accommodate that format anymore,

at the very most — more likely there were none at all.

Cinemas at that time, as I mentioned above,

would just crop the living daylights out of the movie, to .446"×.825" or, usually, a lot smaller even than that.

(I’ve seen setups of .350"×.700", and I suppose many cinemas committed even worse sins.)

The cropping rendered the film entirely incoherent.

Paul should have optically reduced the image to .620"×.864", and that would have solved many problems.

A full-aperture print of The General would be rendered senseless if shown in widescreen.

A reduced sound-aperture print of The General could withstand a widescreen crop, easily, happily.

Cinemas, which were no longer in the habit of hiring full-time musicians, would likely have run the movie without any musical accompaniment.

|

Original |

.446"×.825" widescreen crop |

Almost no commercial cinema on earth will correct this problem.

Why not?

Two reasons: 1. The vast majority of cinema owners, managers, and personnel can’t tell the difference.

2. Cinema owners, managers, and personnel are fully aware of that of the world’s 7,000,000,000+ people,

there is a grand total of 1 who cares, and that 1 no longer attends commercial cinemas.

|

|

Now that we’re looking at this image, we might as well explore it.

This was the first scene shot for The General.

Fans of The General had long wondered where this scene was filmed.

There were no over-and-under trestle bridges anywhere near Cottage Grove.

Well, the Bridgehunters finally found it!

It was at Black Rock, Oregon, just west of Dallas, about 95 miles north of Cottage Grove.

Click on that Bridgehunters link

to read the details.

|

|

|

I know for certain that Paul offered 16mm silent prints of The General for bookings to film clubs.

I know that because I saw one

in Albuquerque in January 1975, and it opened with a

Films, Inc. logo.

The 16mm edition of the movie popped up here, there, and everywhere.

When had Paul first offered the 16mm edition for rental?

I wish I knew.

Most likely between July 1970 and September 1971; that’s my guess.

|

|

A ha! The Winter 1984 catalogue was issued circa September 1983, and so that was when

Killiam licensed Bill Perry’s score to Blackhawk

for its Beta and VHS editions of the movie!

Mystery solved.

I purchased the VHS as soon as I learned about it, probably in 1985, maybe in 1986.

|

|

At some time or another, Paul added Bill’s piano score to some 16mm prints.

I never knew about that until

Juan Carlos Vicente posted this on YouTube:

|

|

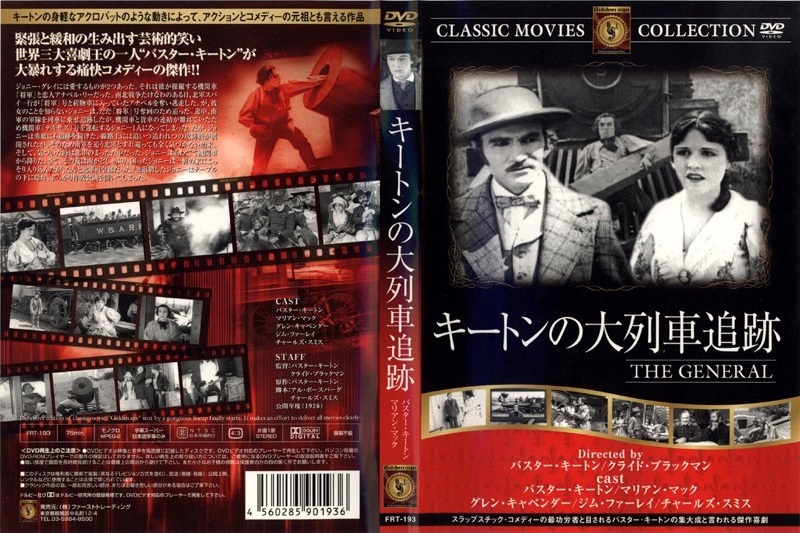

https://youtu.be/UwQCFSeOmdE “El Maquinista De La General”, Buster Keaton, 1926. Película completa, subitulada en español Sep 26, 2016 When YouTube disappears this, download it. |

No idea why the locomotive was touched up or why 5 was changed to 9. K27-206, ???, K27-167, ??? |

|

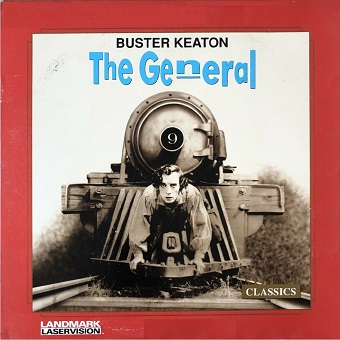

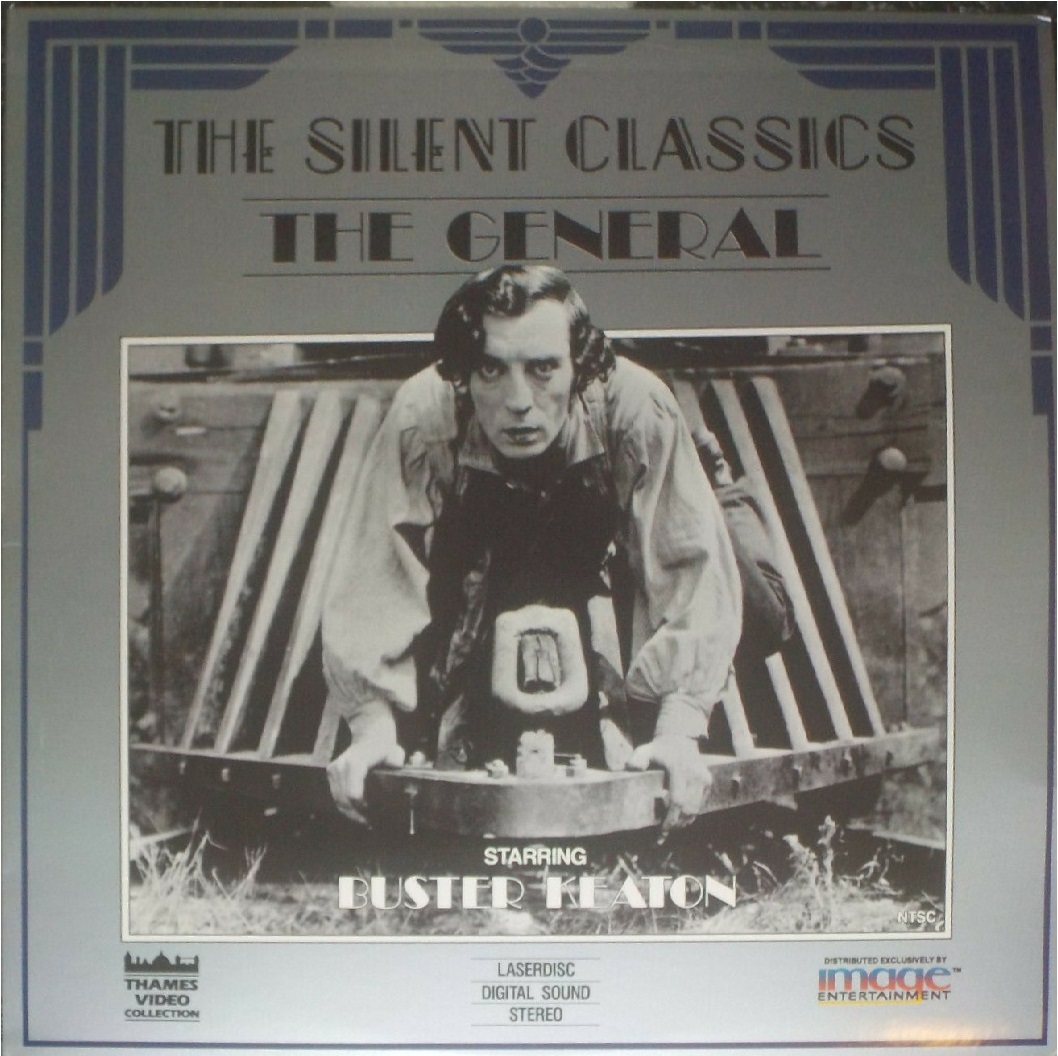

Paul’s tinted TV edition with Bill Perry’s score

was issued on a Landmark Laservision laserdisc, #LV21476, distributed by Republic,

released 18 December 1991.

On the back cover is a publicity still that I’ve never seen anywhere else,

with Johnnie under the table at the Union rendezvous, but in a different pose.

Oh. I see it was also issued on Republic VHS in 1992.

I discover that Killiam had also licensed this tinted version to Channel 5

(1 Rockley Road, London W14 0DL) for PAL VHS release in 1986.

|

Also licensed to Continental in Spain at sometime or another. |

|

Over the next six years or so, Killiam Shows came to add a few more Buster films to its catalogue:

a copy of

Cops (organ score by Gaylord Carter) with the middle of the film deleted,

a rejected preview print of

The Blacksmith (the editing-shed edition, piano score by William Perry),

The Balloonatic (organ score by John Muri),

College (organ score by John Muri), and an alternative (export?) and a sometimes

|

|

Killiam was not the first to make such duplications.

For his 1968 16mm compilation,

The Great Stone Face,

Vernon P. Becker had surely used the MoMA materials as sources.

I have

The Great Stone Face on VHS and DVD but I am unable to watch it all the way through.

That compilation achieved the remarkable effect of making Buster entirely dull and tedious.

It is usually a bad idea to run one comedy short after another after another.

One is a delicious dessert.

Two are too rich, the second film conflicts with the effect of first,

and even if the second is far superior and far more enjoyable, it falls flat.

Three is force-feeding.

Four is torture.

It doesn’t help when the prints are many generations removed from the originals.

It really doesn’t help when a narrator talks us through to explain to us what we are seeing and why it is funny.

The surest way to make something unfunny is to explain why it is funny.

Narration can be done effectively, but only in small doses.

Bob Youngson had a nice formula for his few feature compilations;

he knew how to do it properly, and he included well-placed excerpts, not entire shorts one after the other.

I feel sorry for anyone who was introduced to Buster via The Great Stone Face.

That, I am sure, served only as aversion therapy and drove potential fans away forever.

The movie was so bad that it was not released in the US.

Rohauer gobbled up the rights and then rather bury it in an unmarked grave,

he licensed it to British television and to German VHS.

The movie seems eventually to have had some sort of brief cinema releases in

Italy and

Spain and Argentina, though, surely enlarged from 16mm to 35mm, which I am certain made the images even more painful to look at.

Oh my heavens!

The Great Stone Face WAS issued in the United States!

It played at the Harvard Exit in Seattle on

Friday, 23 December 1977.

Ouch!

|

|

Getting back to Cops, in the Killiam edition, the final minute or so of the first reel is missing.

It could be that, being tightly wound at the core, that part of the film had simply bubbled away to nonexistence.

Maybe.

I suspect that it was Killiam who snipped it out

in order to make it appear that he had used a

|

Jay Ward’s “Sound Version” of 1970 |

|

I mentioned Jay Ward Productions’ “sound version” of The General several times above.

You may even someday run across it yourselves, though it is no longer in release and has never been issued on home video, as far as I am aware.

This was optically reduced from the original

|

|

There is some background here.

It was in 1961 that Jay Ward and his business partner Bill Scott began work on a TV series called

Fractured Flickers,

featuring clips of old films licensed from Rohauer, ridiculously edited together and given preposterous

|

|

The first I knew about the Jay Ward version of The General was on Saturday, 10 April 1976,

when The Guild in Albuquerque

cropped it at undercut 1:1.66 widescreen, .497"×.800", and ran it misframed, with only the bottom of the image showing on screen.

Curious about what I had just witnessed, I visited the Hoffmantown branch of the Albuquerque Public Library,

looked through Reader’s Guide, and discovered a reference to Paul Warshow’s

negative review of this version,

“More Is Less: Comedy and Sound,”

in Film Quarterly vol. 31 no. 1 (Fall 1977),

|

|

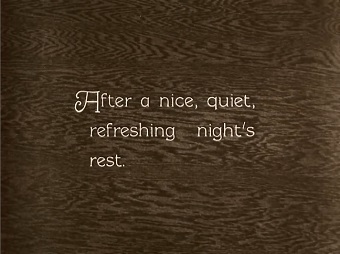

SOME CHOICE EXCERPTS FROM

PAUL WARSHOW’S REVIEW:

...Let us deal first with the less serious change: the

changing of the intertitles to subtitles superimposed

over the images — and, in at least one case,

the complete elimination of the text of an intertitle....

In this print the text of at least one title has been

dropped entirely. Escaped from the Union men, as

well as from a bear, Johnny (Keaton) and Annabelle

huddle together (he kneeling awkwardly with

his arms around her, she sitting with her head on

his shoulder), frightened, in the woods in late

evening in the middle of a drenching storm. Fade-out.

In the original a title appears: “After a nice,

quiet, refreshing night’s rest.” Fade-in to almost

the identical shot, only better-lit, with the two in

the same uncomfortable position. Whoever decided

to eliminate the title and follow the dark shot

immediately with the brighter one may have

thought this would improve the joke by making it

“purely visual” and more subtle for they may have

decided that, since the text couldn’t work as a

subtitle, it had to be eliminated). But the title,

both as a text and as a rhythmical “beat” or

“rest,” is an essential part of the joke, and eliminating

it attenuates the joke to practically

nothing.

But the really terrible change is in the sound

track: in the addition, along with the music, of

realistic, quasi-synchronous sound. While Johnny

is trying to escape silently with Annabelle from the

Union headquarters, a window falls down on his

hands: this print supplies the realistic sound of the

window falling and landing. A group of soldiers

takes aim, smoke rises from their guns, enemies

fall dead: this print supplies the sound, as realistic

as in any sound film, of the guns going off (indeed

most of the realistic sound in this print is the sound

of gunfire).

On the face of it this change offers us More, but

in fact it gives us immeasurably Less, because it

temporarily destroys the film at its roots — as it

would with any silent comedy. For the absence of

realistic sound is silent comedy’s defining element,

its very foundation. To add realistic sound is to

destroy this foundation and throw off the delicate

balance between stylization and realism that enables

the comedy to work....

It must be admitted that the people who added

the realistic sound to this print have exercised a

certain amount of restraint. They have not inserted

realistic sound in all the places they could have,

only in some, so the comic world is destroyed only

in patches, temporarily. The musical score, on the

whole, is appropriate and, as musical accompaniment

generally does, helps push the film in the

direction of greater stylization, both when the

music is the sole accompaniment and when it is

joined by the realistic sound (which pushes the film

in the opposite direction: toward realism). The

film is still funny. It is simply less funny, funny less

often, than it was....

It’s true that the distributors also have silent

prints available.... Raymond

Rohauer says he prefers to watch the silent

“authentic” version, which he says should be

shown with live accompaniment, but says that version

is for “purists”; and he approves the showing

of the sound version to the “mass audience,” who

“just want to have a good time on a Saturday

night.” To prove that this is the version the mass

audience “wants,” he puts forth the information

that “they” have “never complained.” But this is

just a new instance of an old commercial sophistry,

fallacious on several counts. First of all, most

members of the “mass audience” aren’t conscious

of the alternatives. If they were, they might not

care or might even prefer a non-“modernized”

version. Second, only a small fraction of those

bothered are going to register a complaint. Third,

anyone who does register a complaint automatically

becomes a “purist” and outside the “mass

audience.” And, finally, even if it could be shown

that there is a “mass audience” that prefers bastardized

versions of a great artist’s work, that

would hardly prove that the right thing is to give

them these versions.

Moreover, the choice supposedly offered by the

distributors, between the showing of this sound

version and an authentic showing of an authentic

version, is more apparent than real. Besides the

bastardized sound version, the only versions the

distributors offer us have no sound track —

and, as Rohauer indicated, are meant to be shown with an

appropriate live musical accompaniment. But live

accompaniment of silent films is pretty much a

thing of the past. It is still done at New York’s

Museum of Modern Art and maybe one or two

similar places, but only a few theaters have it, and

they are ones devoted to camp nostalgia. Thus,

from the standpoint of sound, all the 35mm prints

available are inappropriate — for the choice the

distributors really offer us is between the bastardized

sound version and one of their silent versions

shown without accompaniment. The “silence” (in

other words, the sound of the audience and other

ambient sound) that occurs in the latter case,

while preferable to this sound track, is likewise

inappropriate, for silent films were meant to be

shown with a fitting musical accompaniment,

which itself provides an important element of

stylization....

It is ironic that the man who has sanctioned this

violation of The General (the changes were actually

carried out by Jay Ward Productions, to whom he

leased the rights) is Raymond Rohauer — for next

to Keaton himself, Rohauer is the person to whom

present-day Keaton lovers owe the most. Not only

is he responsible for the films’ current 35mm distribution;

he also restored the films and brought

them back into distribution at a time when Keaton’s

reputation was in eclipse. And a beautiful job

of restoration it was: whatever complaints one has

about the sound print of The General, its pictorial

quality is superb. From all the evidence, Rohauer

has been motivated not only by commerce but also

by a genuine love for Keaton’s work. But we

should not let our gratitude to Rohauer inhibit us

from protesting strongly against the desecration of

Keaton’s work that he has recently authorized.

(Incidentally, this sound print of The General has

“Produced by Raymond Rohauer and Jay Ward

Productions” in the credits, leading anyone who

doesn’t know better to think these fellows were

actually around helping Keaton make the film.)

The issue, of course, extends far beyond The General.

Jay Ward Productions, who made the

changes in this print, are now at work making

sound versions of all of Keaton’s silent features —

and these will be the only sound versions available

in 35mm. If they go on thinking that the kinds of

changes they made in The General are just fine —

are, moreover, what the public wants — they are

going to make the same sorts of changes in the

other films. They will go on changing intertitles to

subtitles and are likely to become even freer in the

adding of sound effects, the complete elimination

of titles, and who knows what other changes. And

the distributors of other silent films will follow suit.

And if the distributors decide that bastardized

versions are what the public wants, they probably

won’t bother to keep authentic versions in distribution.

In fact they might not even bother to preserve

authentic versions. Things might reach the

point — and this would be tragic — where the

authentic versions were lost forever.

One crucial difference between the desecration

of films from passivity and the desecration of films

in the name of active improvement is that the

latter, unlike the former, is based on an assumption

about what the public wants. This makes the

latter easier to deal with, for if the distributors can

be convinced that these “improvements” are in

fact something the public does not want, they will

desist. We should protest now, making it clear to

the distributors that we do not want these violations

and that we will not allow them to be made without a fight.

Rohauer’s address is Suite 16B, 44 West 62nd St., New York, NY 10025.

To my surprise, Warshow was correct to claim that the only edition in the US with a soundtrack was the Jay Ward edition.

Rohauer prints with an Erwin organ score would not be made available for regular bookings until 1979.

Is Paul Warshow still amongst us?

Is there a way to reach him?

If so, please let me know.

Thanks!

|

|

In trying, just now, to get the

|

|

No, it was most definitely not created in 1953.

Wikipedia further claims that Rohauer renewed the copyright in 1983.

Something is off there, totally off.

Whatever the case, it was The Raymond Rohauer Himself who infected the record.

Behold:

|

|

Huh? Ray backdated his copyright application and faked it. Total fraud. That’s all. Nothing more.

The above copyright registration predates Jay Ward’s edition.

|

|

I just received

Keith Scott’s book, The Moose That Roared: The Story of Jay Ward, Bill Scott, a Flying Squirrel, and a Talking Moose

(NY: St. Martin’s Press, November 2001).

When we turn to pages 299–300, we read:

|

|

Bill Scott produced a couple of commercials for various causes like the

Mental Health foundation, using Ward Productions facilities. Then in 1974,

he began work on several new compilation live-action films for release by

Ward Productions. These were along the lines of the earlier

Crazy World of

Laurel and Hardy. Taking advantage of his passion for classic motion-picture

comedy, Bill wrote, narrated, and assembled some fascinating retrospectives

on comedians Buster Keaton (The Golden Age of Buster Keaton), W. C. Fields

(The Vintage W. C. Fields), and Robert Benchley (Those Marvelous Benchley

Shorts). All featured lengthy and representative film clips, along with nice

cartoon links animated by some of Ward’s favorite artists, like Phil Duncan

and Ben Washam. The Keaton films, deposited years earlier in Ward’s vault

by Raymond Rohauer, were simply too good to leave gathering dust, while

the rights to further comedy films had slowly been acquired by Ward. As

Bill Hurtz explained, “Jay had purchased the old films as an investment.”

These compilation features were lovingly completed by Scott and Skip

Craig over several years. Skip remembered, “Bill and I didn’t have a real

system, it was pretty loose. He’s come in most days and run the films on a

Movieola, and smoke up the place with those cigars of his, which I hated.

He’d just mark a roll of film and yell for me, and I’d do whatever he

requested: sometimes he’d switch the sound track for an effect, and he’d

theme the pieces of film. The first one was the W. C. Fields movie. There

was a sequence in there that no one had seen for thirty years from Tales of

Manhattan. We finished it, but our Fields film never played; we’d done

some little animated bridges in which Bill imitated Fields’s voice. But the

Fields estate wouldn’t allow it to be released; of course, Jay refused to take

the bridges out, so that was that.

“Then we did the best of our live-action films — Keaton’s feature The

General. This time we got the full-aperture fine-grain print from

MGM, and it was beautiful quality. Rich Harrison put in the sound effects, and

Joe [Siracusa] did the music again. We recorded some narration, but we hardly

had to touch the film — except we took out most of the dialogue cards, and

stuck in some maps and explanatory things. It was a gorgeous picture, and

I actually got to fix a tiny cut that Keaton had goofed on — he used to cut

all his own pictures. It played recently on HBO.

“The last one we did was the Benchley feature....”

|

|

That’s another curious story, is it not?

So many things wrong.

So many, many things wrong.

What else is new?

Let’s do a little checking.

The Golden Age of Buster Keaton

was released in 1975.

Except that it wasn’t.

It was ready for release in 1975, but no distributor was interested.

There are some vague indications that

The Vintage W. C. Fields

was indeed released to cinemas, also in

1975, but I don’t think that happened.

It seems more as though a release was announced but withdrawn before a single booking.

The Fields movie was definitely shown on HBO, though, in

August 1979.

I have a Rohauer catalogue in my possession that makes clear that The Vintage W. C. Fields was available only on broadcast videotape.

Now it begins to look like Skip Craig’s memory is partial.

The Benchley compilation was not released.

|

|

Now we get to The General.

According to Keith Scott and Skip Craig, this was the third production,

and so could not possibly have been released any earlier than 1975.

Skip Craig mentioned the narration, but there is no narration in the release edition of the film.

Perhaps there was in a

|

|

Oh. I was just chatting with a friend, and he instantly figured out why.

In 1947 or or 1948, MGM optioned remake rights to The General.

MGM needed a reference print, and so paid United Artists to run one off.

That’s why.

Buster’s part would be played by Red Skelton, and Buster would be on staff to supply gags.

The movie never happened, probably because the cost was prohibitive.

Instead, MGM, Red, and Buster worked on a different Civil War yarn called

A Southern Yankee.

I’ve seen bits and pieces of it, and it looks bloody awful.

It doesn’t look like a movie; it looks more like third graders putting on a school play.

I guess I’ll force myself to sit through it some year.

Another tenuous

|

|

It just now occurs to me.

It was in 1969 that MGM was purchased by real-estate developer Kirk Kerkorian in a hostile takeover,

and much of the archives — paperwork, props, costumes, film, music, and so forth —

were destroyed or auctioned off.

Could that be why the

|

|

Something else occurs to me.

When Bill and Skip made a copy negative from the

|

|

Of course, I’m being ridiculous.

Bill and Skip did not make two copy negatives from the

|

|

Then we get to another problem.

Skip Craig said that this string of work on these four features began in 1974.

No it didn’t.

Take a look at the poster for the Jay Ward version

of The General, and you will see that it has a 1970 copyright date.

|

|

Detail:

|

|

Oh, that G rating, it was fake.

These flicks were never submitted to the MPAA’s rating board.

|

|

The opening credits erroneously provide a 1969 copyright, a 1969 copyright notice that would be visible on American widescreens.

Yes, the Jay Ward edition of The General was shown in American widescreen.

The entire height of the image was on the reformatted Academy-aperture film,

but I am quite sure that not a single cinema anywhere showed the full image.

Bill Scott and Skip Craig and their crew were fully aware of the format mismatch,

but it is clear what they did.

After they reduced the image to Academy .620"×.864", they tested it by running it at American widescreen .446"×.825"

in order to see what adjustments they would need to make.

To their delight, all the action fit through that smaller aperture.

Some of the cropping was too tight, but it never, not once, not for a single frame,

deleted any essential action.

So they performed no further reformatting, and, to my astonishment, it worked.

|

|

So there we go, once again: Proof that I was not only wrong, but totally, completely, absolutely wrong.

Time for rewrites.

I know from years of painful experience that pretty much any older film can be cropped to widescreen

and in most scenes it will play just fine.

Framing in most movies is quite loose and the edges can be sacrified, usually.

If you run an older movie in widescreen, though, no matter how nicely it plays that way,

sooner or later there will that that scene, that dreaded anticipated scene,

that scene that does not fit, that does not even come close to fitting,

that is utterly senseless on widescreen.

So typical. So inevitable.

If you run a

|

|

Moreover, Buster and his cameramen usually — usually —

used the rule of thirds, which makes for nicely composed images, extremely loose.

Not always, though.

The rule of thirds allows for dramatic exceptions, and those exceptions would fall off were the image cropped.

Give a small child a camera, and chances are that the small child would snap photos composed per the rule of thirds.

It’s a natural thing to do.

It’s the way we see the world.

Busyness is centered, and objects further from the center are less and less important,

until we get towards top, bottom, left, and right, where the image conveys little or no useful information.

|

|

So, I was not surprised when the first scene of the optical reduction of The General fit at 1:1.85.

I was not surprised when the second scene fit.

Or the third.

Or the fourth.

Or the tenth and running.

What shocked me, shocked me to the core of my being, is that EVERY shot in the movie fits at 1:1.85,

or comes so close to fitting that it almost doesn’t make a difference.

Not just merely fits, but really looks as though it was deliberately composed that way.

Actually, it would fit a little better at 1:1.66, but nonetheless, at 1:1.85 it looks fine,

all the way through, every moment, beginning to end.

This is not an accident.

This is not a coincidence.

If it fits that close to perfectly, with perfect consistency,

and if the heads consistently line up exactly at the 1:1.85 safe area, which they do,

that can only mean that it was intentionally composed that way.

WHY???????

|

|

I went through the Kino K669

|

|

What on earth was Magnascope?

Screens in those days were pretty small.

In a gigantic movie palace, the screen might be a mere 15'×20'.

With Magnascope, there was a change.

Enormous screens were installed, but they were mostly covered by black cloth.

To the audience’s eyes, the screen looked normal, just like the regular 15'×20' screen.

But then, lo and behold, when a particular dramatic moment or action scene would begin,

there would be a switch to a different projector

with a lamp burning at a higher amperage and with a shorter lens (or with an enlarger attached to the regular lens).

The stagehands would open up the black maskings at the top, left, and right, and the image would appear to grow to mammoth proportions.

In its original conception, there was to be no crop.

The entire image would grow.

Few cinemas could accommodate such, and so the height was cropped.

|

|

A colleague forwarded me a vintage article by Harry Rubin,

“The Magnascope,” The Motion Picture Projectionist, November 1928, p. 13.

Probably no two cinemas had an identical installation,

but Rubin published a diagram of a suggested setup:

|

|

Note that the suggested crop has a height-to-width ratio of 1:1.60 !!!!!

I am not certain about this, but it seems to me that it would have been possible to open the maskings even a little further.

If so, the resulting ratio would have been about 1:1.75, which is an even more severe crop.

|

|

Shall we quote from Carr & Hayes?

Wide Screen Movies (Jefferson, NC: McFarland, 1988), pages 5 through 9:

|

|

...A projection lens was

developed in 1924 by Lorenzo del Riccio that enabled the enlargement by

four times of any 35mm scene on the screen. Paramount put the unit to use

on North of 36 and

The Thundering Herd in 1925,

and Old Ironsides in

1926. It was utilized on several other features from that studio as well as

other distributors. Initially the idea was to cover the screen in a ratio of

1.85 × 1 or whatever shape filled the stage proscenium arch. In fact the ratio

varied from 1 × 1 (in a New York theater) to slightly over 2 × 1, depending

entirely on the layout of the theater. Magnascope was meant only for

selected scenes, though many theaters used it on many, or all, of their features

to heighten the climax regardless of the subject. Westerns particularly

received Magnascope presentation....

Despite popular belief, cropping was not limited to a few big theaters

in a few large cities. Many small neighborhood theaters had acquired enlarging

lenses and would still be using them when cropping became the

official industry standard for spherical 35mm wide screen in the early fifties.

In those theaters the wider image so hyped by Hollywood would be nothing

new. Cropping had, in fact, become so common by 1930 that veteran cinematographer

Gilbert Warrenton suggested to all in the industry that a 2 × 1

safe area be included in the framing of all features, thus allowing the many

houses already filling their wide screens the benefit of prints that did not require

constant frame adjustment by projectionists. Others also backed such

an idea, most thinking the 1.85 × 1 ratio was better. The studios, however,

ignored these suggestions and continued with 1.33 × 1 framing until cropping

was adopted as part of the war against television. Little by little most

theaters replaced their wide screens for smaller, narrower 1.33 × 1 ratio size.

But some still kept the wider shape. (The authors know of two theaters that

used undersize apertures, as the projectionists called them, to render wide screen

presentation from the late twenties on. Both these cinemas were in

small towns, one in Georgia and one in Alabama!)

|

|

The above passage includes one of Carr & Hayes’s few errors:

North of 36

premièred not in 1925, but in December 1924.

There is also a bit of careless writing.

In one paragraph, they state that Magnascope was used only for climactic scenes.

In a later paragraph, they imply that some cinemas used Magnascope exclusively, not just for select scenes.

A transition was missing, a transition that made the evolution clear.

At first Magnascope was used only for climactic or especially action-filled scenes,

but soon it came to be used for everything.

A minor quibble is the reference to Lorenzo del Riccio, an engineer/inventor employed by Paramount Pictures.

His enlarging supplement was not the only available method to fill a Magnascope screen.

Another method, employed by a few or some or most cinemas, was simply to purchase lenses of a shorter focal length,

as we learn from Harry Rubin’s article.

|

|

The Bell & Howell 2709 had only a parallax viewfinder available as the camera was running.

Yes, it also had a more accurate viewfinder, true, but it was not available during the actual shooting; it was only to line up shots.

Nonetheless, the parallax viewfinder had

|

|

When did Magnascope make its first appearance?

One source suggested December 1926.

Well, if that was true, then the framing of The General must have had another explanation, certainly æsthetic.

Then I learned from that Carr & Hayes passage above that, no,

Magnascope had been in use for a year and a half before The General began production.

Once I learned that, it all made sense.

The General, with camera apertures of about .723"×.980",

was absolutely designed to withstand something like a .566"×.90625" crop.

Now, it does not follow that the film should be cropped.

Some scenes look better with a crop, but other scenes look better without a crop,

especially the routine with the railroad cannon.

Please do not crop the movie.

|

|

Thirty years later, that photographic compromise led to a happy result,

for the safe area almost exactly matched the 1:1.66 crop so common in the US beginning in 1953 and for the five or so years afterwards.

From about 1960 through about 1985, 1:1.66 was the most common crop outside the US, Canada, and Italy.

Since the framing was mostly quite loose, even a 1:1.85 crop did not harm the film.

(1:1.85, .446"×.825", was the most common crop in the US and Canada beginning in the late 1950’s,

and in Italy beginning around 1963.)

Though such a crop was too tight in some scenes of The General, the movements on screen told us what was happening just inches away.

Thus, even when cropped to 1:1.85, a 28% loss of image, it works, it’s presentable, and it’s every bit as enjoyable.

My mind is totally boggled.

Most video editions, by the way, crop the film, zooming right in to the center of the image and losing all four sides.

|

|

I have now checked all of Buster’s features from Three Ages through Steamboat Bill, Jr.,

and I used the Kino

|

|

Below is a poor copy of a VHS recorded from the Showtime cable transmission.

This is courtesy of a collector I met online.

Sorry about the defects, the darkness, the softness, and the

|

|

The General was released by Joseph Brenner Associates, Inc.,

which seems to have had a prior agreement with Ward to be exclusive US distributor.

I’m learning a little bit.

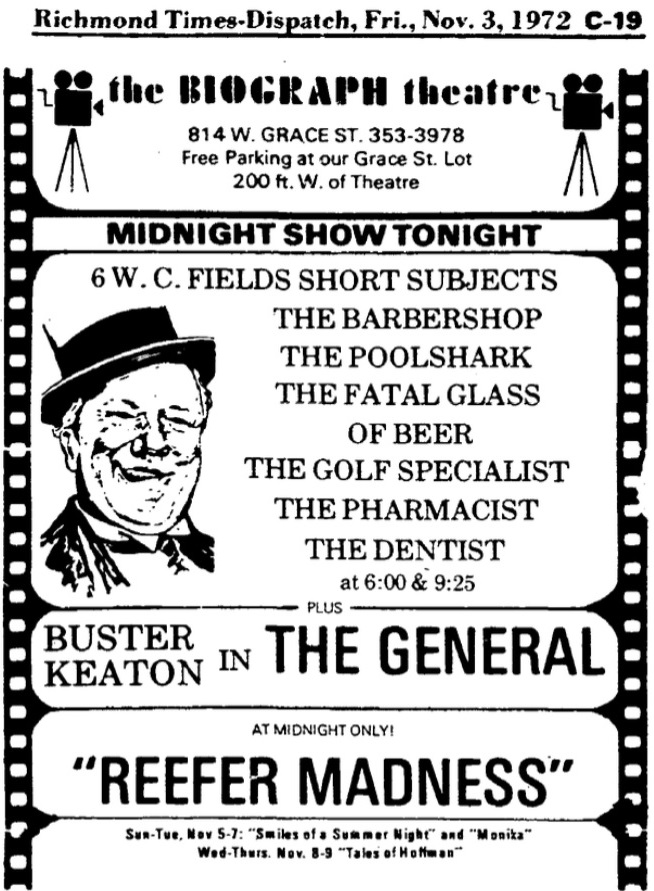

One thing I learn is that in 1968 Rohauer released The Best of W.C. Fields through Joseph Brenner Associates.

If you’re curious, The Best of W.C. Fields was merely three short films one after the other:

The Golf Specialist, The Fatal Glass of Beer, and The Dentist.

At least, that was the

|

|

Then remember the program notes that Ray wrote for the BFI’s National Film Theatre in January 1968?

Look again.

Ray gave his address as c/o Joseph Brenner!

|

|

Despite Rohauer taking a production credit on this new edition of The General, this was not a Rohauer release.

Despite this being a Rohauer title in the Rohauer Collection, this edition was not derived from any of Rohauer’s materials.

I just spent the better part of a day trying to trace down some bookings

of this package of The General and A Night with the Great One.

|

| OPENING | CITY | VENUE | RUN | NOTES | |

| Fri 25 Sep 1970 | Scranton, PA | Courthouse Square | 1 day | Outdoor screening during a concert | |

| Wed 30 Sep 1970 | Ferndale, MI | Radio City | 7 days | ||

| Wed 07 Oct 1970 | Doraville, GA | Doraville Mini Cinema | 7 days | ||

| Wed 07 Oct 1970 | Doraville, GA | Peachtree Battle | 7 days | ||

| Wed 07 Oct 1970 | Minneapolis, MN | Varsity (Mann) | 7 days | ||

| Wed 07 Oct 1970 | St Paul, MN | Grandview (Mann) | 7 days | ||

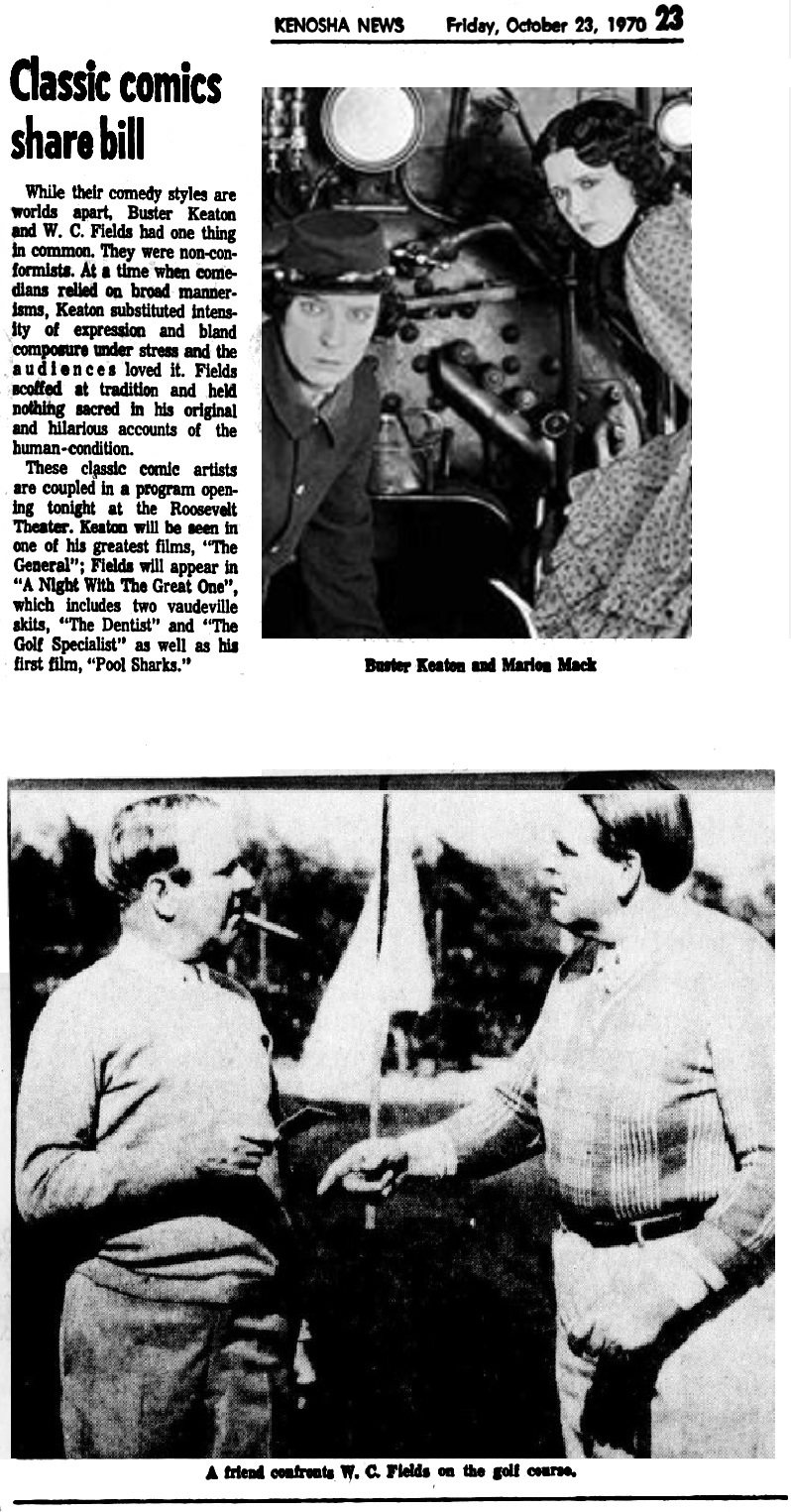

| Wed 07 Oct 1971 | Milwaukee, WI | Downer Theatre | 14 days | review | |

| |||||

| Fri 16 Oct 1970 | Memphis, TN | Guild (Art Theatre Guild) | 7 days | ||

| Fri 16 Oct 1970 | East Lansing, MI | State (Butterfield) | 7 days | ||

| Fri 16 Oct 1970 | Minneapolis, MN | Campus (Mann) | 7 days | move-over | |

| Fri 23 Oct 1970 | Kenosha, WI | Roosevelt Theater (Indep.) | 5 days | review | |

K27-200 | |||||

| Wed 28 Oct 1970 | Petersburg, VA | Bluebird (Indep.) | 7 days | ||

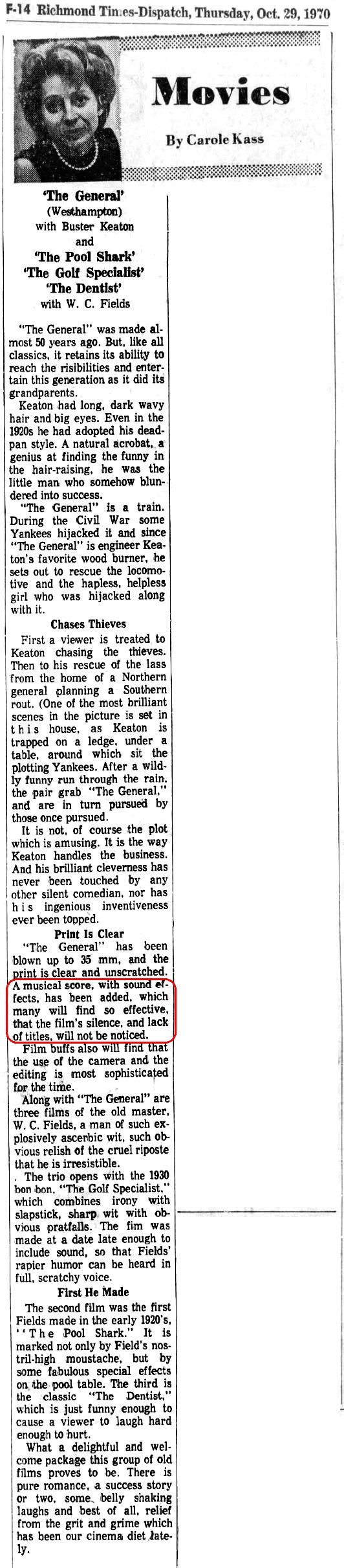

| Wed 28 Oct 1970 | Richmond, VA | Westhampton (Neighborhood) | 7 days | PR, review | |

| |||||

| |||||

| Wed 04 Nov 1970 | Annapolis, MD | Capitol | 7 days | ||

| Wed 04 Nov 1970 | Columbus, MO | Hall Theatre (Commonwealth) | 7 days | ||

| Wed 04 Nov 1970 | Eau Claire, WI | Cinema 1 (Indep.) | 4 days | ||

| Fri 06 Nov 1970 | Wilmette, IL | Wilmette (Indep.) | 21 days | ||

| Fri 06 Nov 1970 | Omaha, NE | Dundee (Wide World) | 7 days | ||

| Wed 11 Nov 1970 | Cincinnati, OH | Esquire (Neighborhood) | 7 days | ||

| Thu 12 Nov 1970 | Charlottesville, VA | University | 3 days | ||

| Wed 11 Nov 1970 | Cincinnati, OH | Hyde Park (Neighborhood) | 7 days | ||

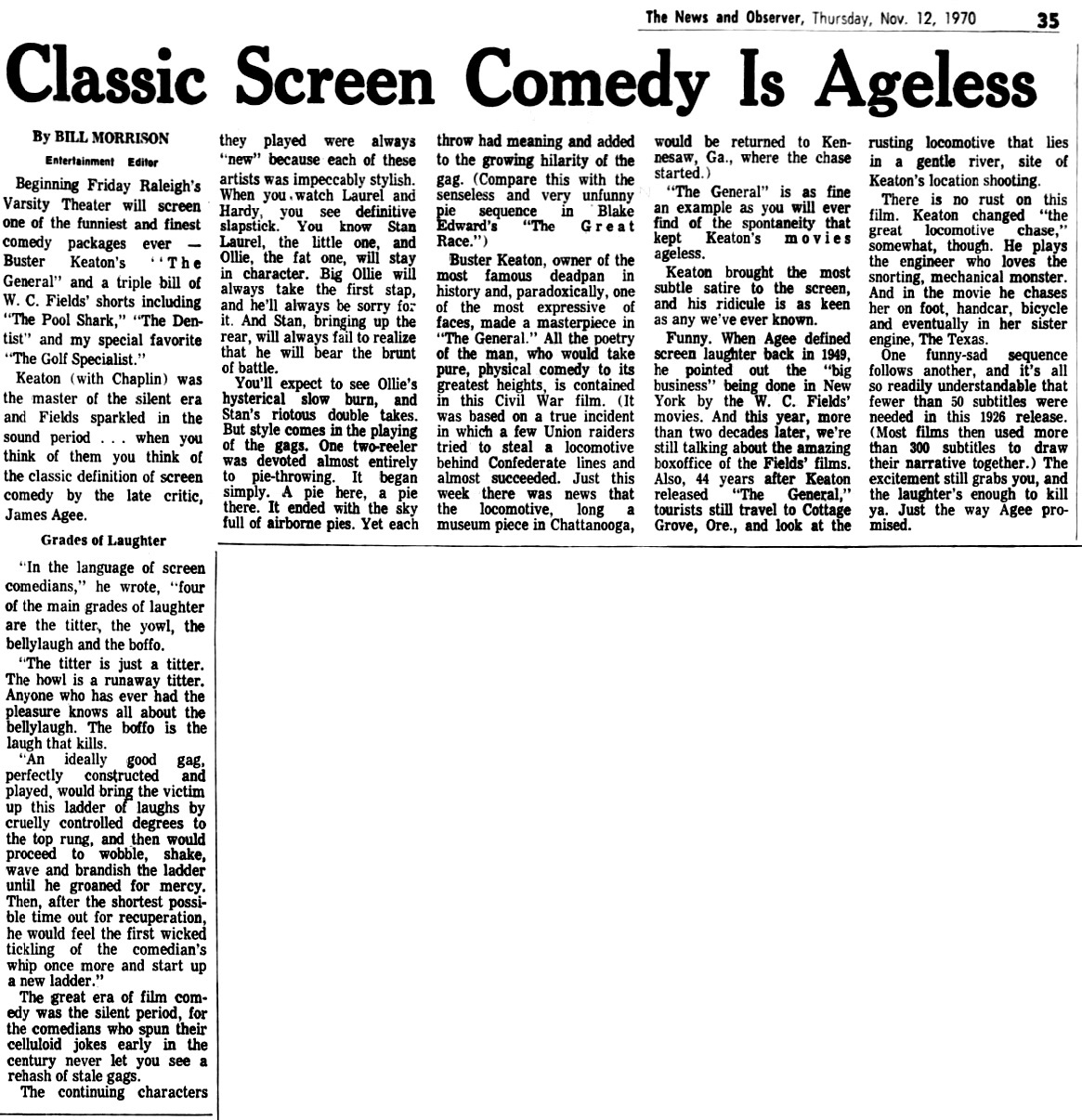

| Fri 13 Nov 1970 | Raleigh, NC | Varsity (Indep.) | 7 days | review | |

| |||||

| Fri 20 Nov 1970 | Rochester, NY | Fine Arts (Jo-Mor) | 12 days | ||

| Wed 02 Dec 1970 | Columbus, OH | University Theatre (GCC) | 4 days | PR | |

| |||||

| Wed 02 Dec 1970 | Kansas City, MO | Waldo (Commonwealth) | 14 days | review, review | |

K27-90 | |||||

| |||||

| Fri 04 Dec 1970 | San Francisco, CA | Richelieu (Indep.) | 7 days | ||

| Wed 09 Dec 1970 | Des Moines, IA | Varsity (Davis) | 7 days | letter | |

The Birth of a Nation (modified 1930 version) was also distributed by Joseph Brenner Associates, Inc. | |||||

| Chapel Hill, NC | Carolina Theatre (Indep.) | press release; this booking seems to have been canceled. | |||

| |||||

| Wed 16 Dec 1970 | Wichita, KS | Uptown (National General) | 7 days | PR, PR, Barry Paris | |

|

The Birth of a Nation (modified 1930 version) was also distributed by Joseph Brenner Associates, Inc. | |||||

|

| |||||

| |||||

| Wed 16 Dec 1970 | Davenport, IA | Coronet (Indep.) | 8 days | ||

| Sat 19 Dec 1970 | Greensboro, NC | Janus 1 | 6 days | PR | |

| |||||

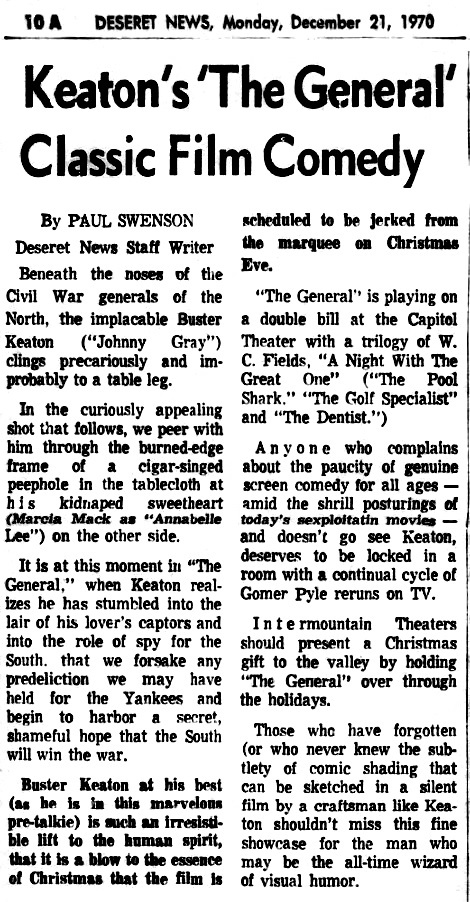

| Fri 18 Dec 1970 | Salt Lake, UT | Capitol (Intermountain) | 7 days | PR, review | |

| Fri 18 Dec 1970 | Salt Lake, UT | Motor-Vu (Intermountain) | 7 days | ||

K27-90 | |||||

| |||||

| Wed 23 Dec 1970 | Baltimore, MD | Little (Trans-Lux) | 15 days | review | |

| |||||

| Wed 06 Jan 1971 | Winona, MN | Cinema (Indep.) | 7 days | ||

| Fri 08 Jan 1971 | Kansas City, MO | Ruskin 2 (Commonwealth) | 5 days | ||

| Wed 13 Jan 1971 | Palo Alto, CA | Paris | 51 days | ||

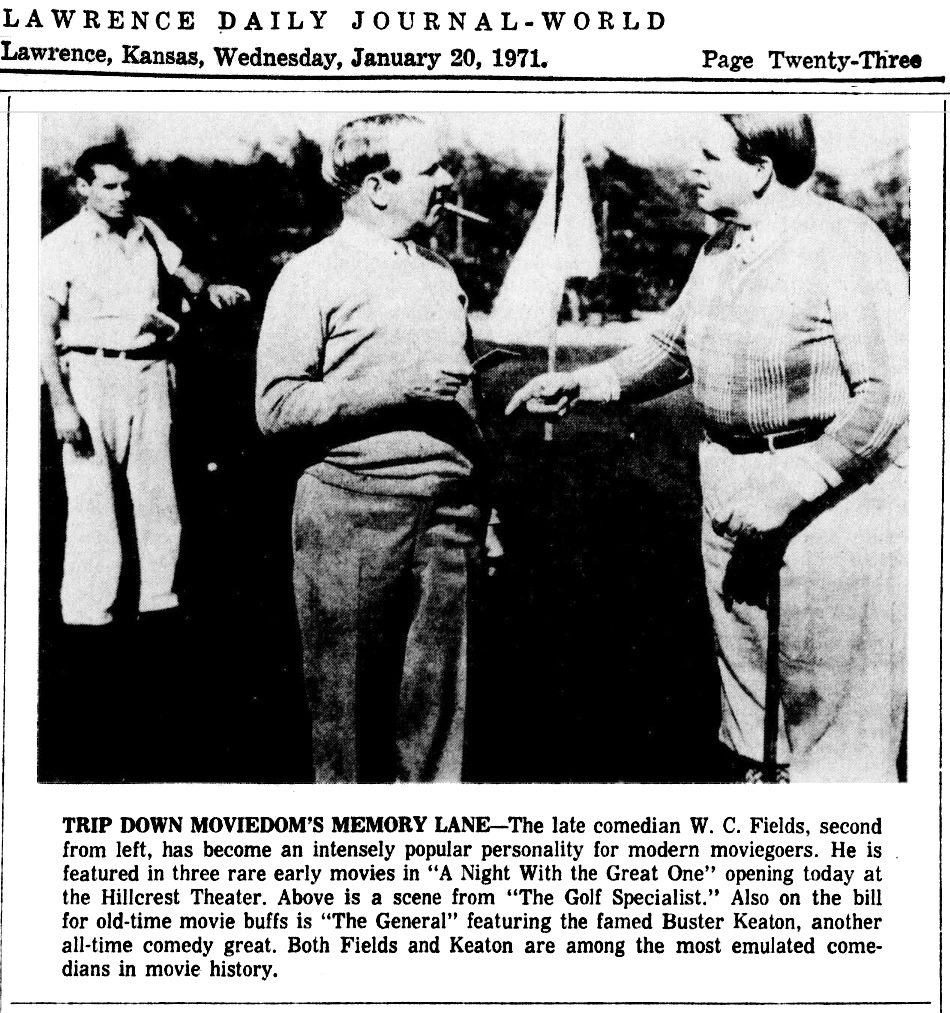

| Wed 20 Jan 1971 | Lawrence, KS | Hillcrest 3 (Commonwealth) | 7 days | PR | |

| |||||

| Thu 04 Feb 1971 | Danville, VA | Park Theatre (Indep.) | 3 days | ||

| Wed 10 Feb 1971 | Buffalo, NY | North Park (Dipson) | 7 days | review | |

The above notice was a bit premature, yes?

| |||||

| Wed 10 Feb 1971 | Burlingame, CA | Encore (Indep.) | 7 days | ||

| Wed 10 Feb 1971 | Fredonia, NY | Cinema 1 | 7 days | ||

| Thu 11 Feb 1971 | Dubuque, IA | Strand (Bradley) | 7 days | ||

| Wed 17 Feb 1971 | Carbondale, IL | Fox | 4 days | ||

| Thu 25 Feb 1971 | Woodstock, NY | Tinker Street Cinema (Indep.) | 6 days | ||

| Fri 02 Apr 1971 | St. Louis, MO | Magic Lantern Cinema (Indep.) | 5 days? | ||

| Fri 02 Apr 1971 | Springfield, IL | Roxy (Frisina?) | 6 days | press releases | |

| |||||

| Wed 14 Apr 1971 | Oak Park, MI | Towne 1 | 7 days | ||

| Wed 21 Apr 1971 | Baltimore, MD | 7 East | 14 days | Boxoffice 03 May 1971 p. E-8 | |

The Crazy World of Laurel & Hardy was also distributed by Joseph Brenner Associates, Inc. | |||||

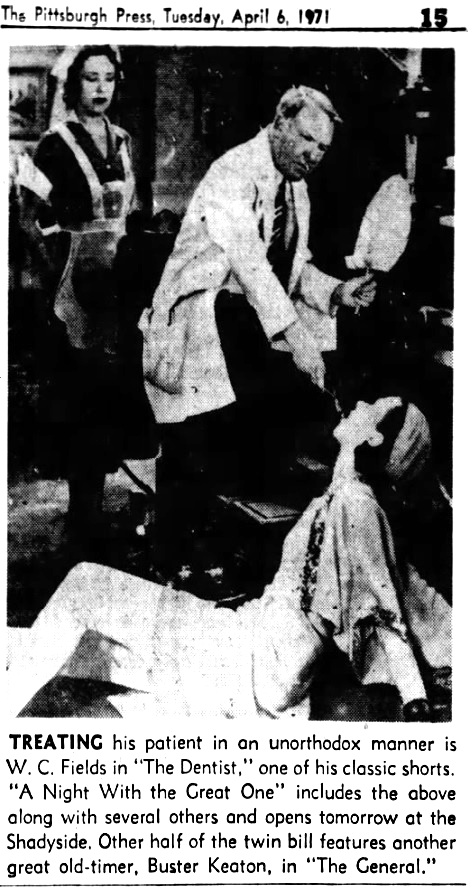

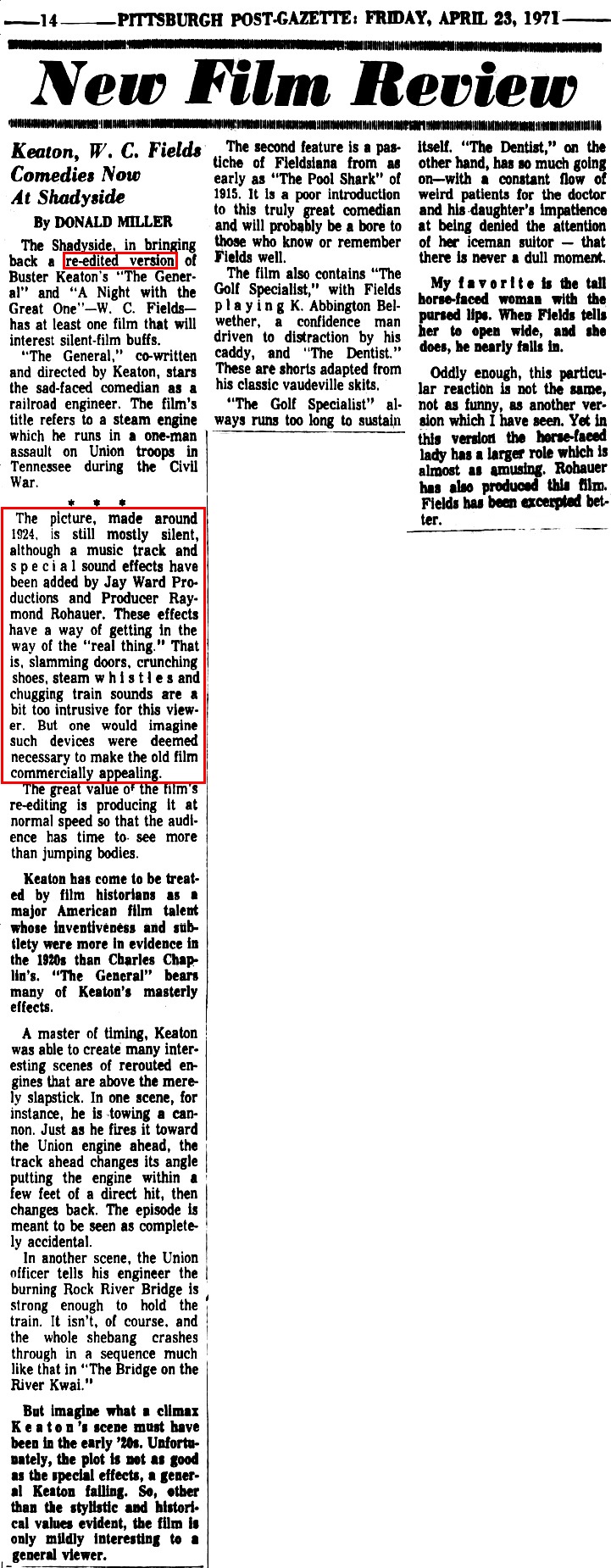

| Wed 21 Apr 1971 | Pittsburgh, PA | Shadyside (Indep.) | 9 days | PR, review, review | |

| |||||

| |||||

| |||||

| Wed 05 May 1971 | State College, PA | Cinema II (Associated Theatres) | 7 days | ||

| Wed 12 May 1971 | Minneapolis, MN | Varsity (Mann) | 7 days | ||

| Wed 12 May 1971 | Minneapolis, MN | Riverview (Volk) | 7 days | ||

| Wed 19 May 1971 | Sacramento, CA | Arden Fair 3 (Indep.) | 7 days | ||

| Fri 21 May 1971 | Ogden, UT | The Movie | 7 days | ||

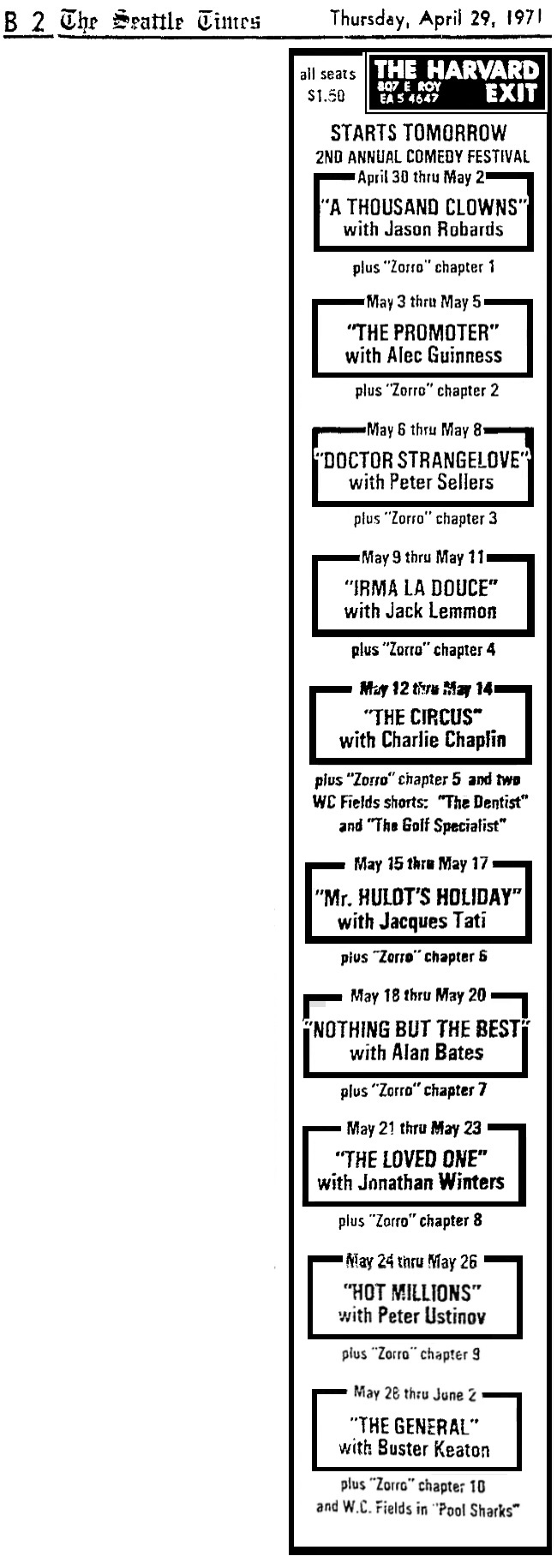

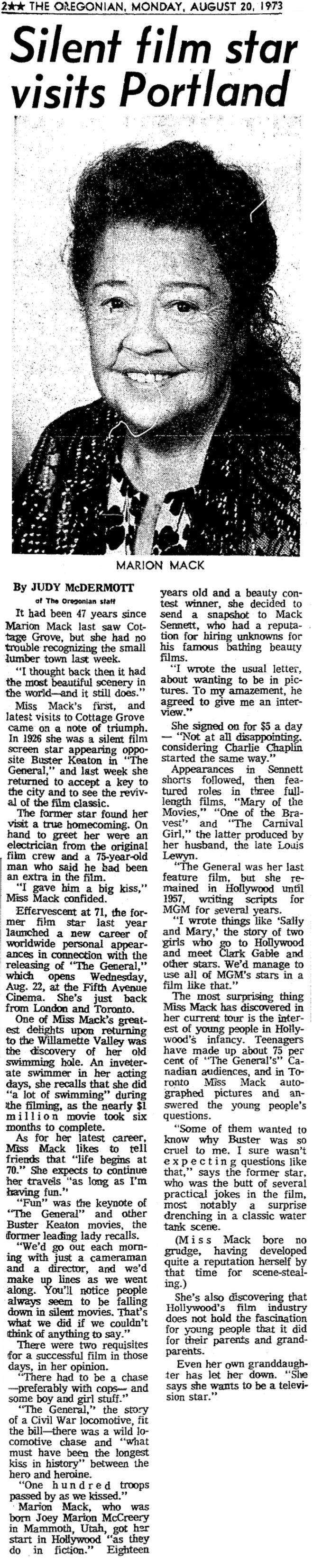

| Fri 28 May 1971 | Seattle, WA | The Harvard Exit | 13 days | Booked 6 days, held over another week | |

| |||||

|

That was the last booking of “The Greats” that I can find anywhere.

Afterwards, The General was booked separately from A Night with the Great One,

but it was often doubled or tripled with other films, which were often also from the Rohauer or Jay Ward catalogues.

| |||||

First time since January 1927, which was 44 years, not 50. | |||||

| |||||

| |||||

| Fri 18 Jun 1971 | Wilmette, IL | Wilmette (Indep.) | 7 days | Boxoffice 21 Jun 1971 p. C-7 | |

| Thu 02 Nov 1972 | Richmond, VA | The Biograph | 3 days | ||

| |||||

| Wed 22 Nov 1972 | Seattle, WA | The Harvard Exit | 9 days | ||

| |||||

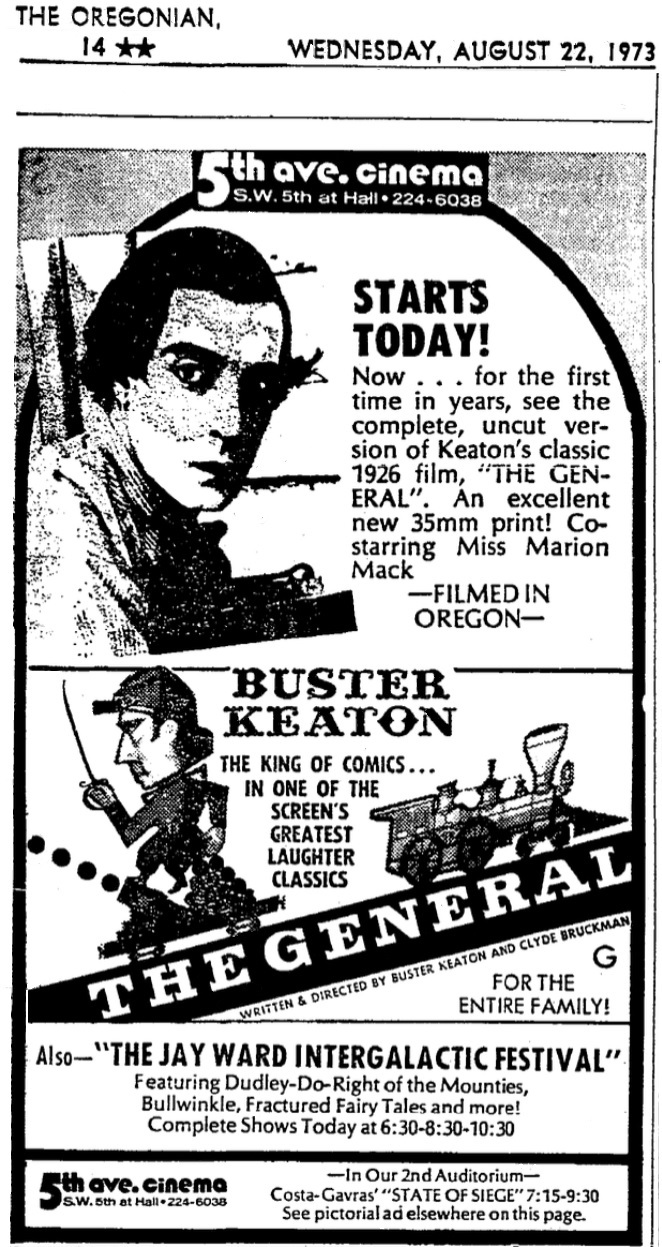

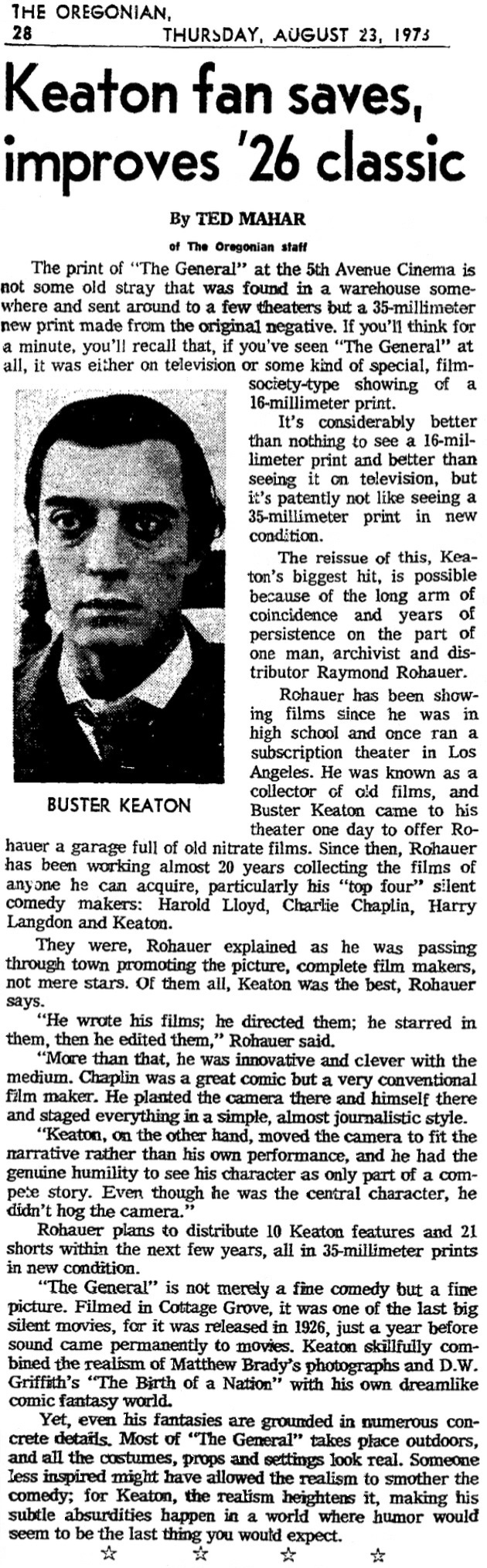

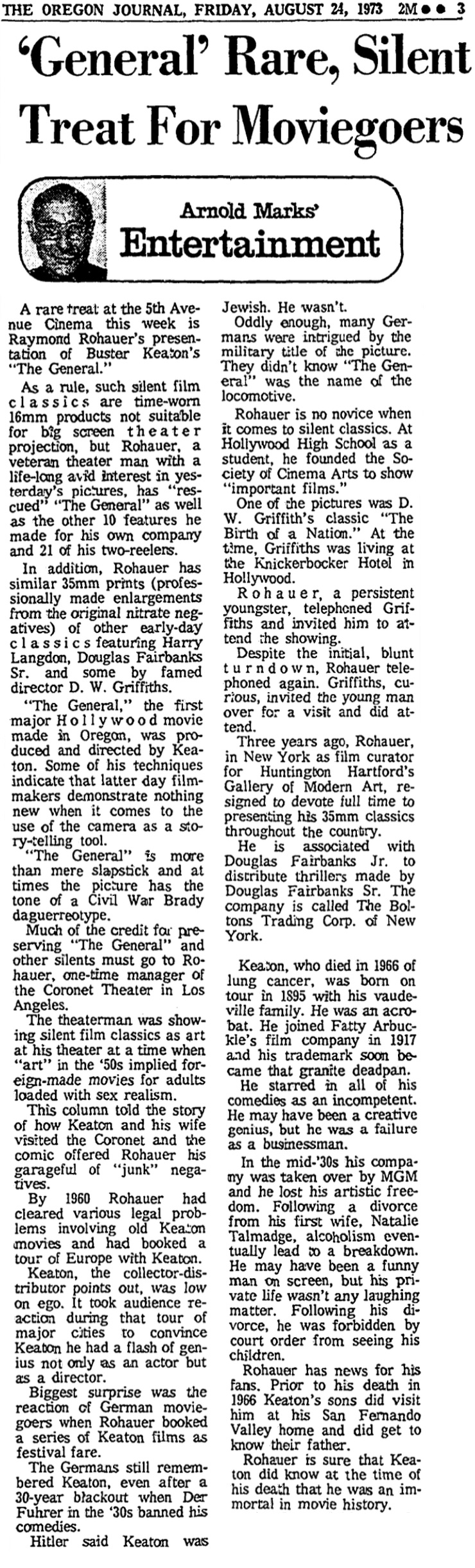

| Wed 22 Aug 1973 | Portland, OR | 5th Ave. Cinema | 14 days | ||

| |||||

| |||||

| |||||

K27-96 | |||||

K27-204 | |||||

| |||||

| |||||

K27-96 | |||||

| |||||

| |||||

| |||||

K27-168 | |||||

| Wed 10 Oct 1973 | Seattle, WA | The Harvard Exit | 7 days | ||

| |||||

| Thu 22 Aug 1974 | Greensboro, NC | Janus 2 | 2 days | ||

| |||||

|

That’s when it appears to have petered out.

|

|

Was it a coincidence that

MGM reissued The Cameraman in April 1968 and Spite Marriage not long afterwards?

Neither had been publicly available

since the 1930’s.

Rohauer had been coining an income with his traveling show.

Maybe it was time for MGM to jump onto the bandwagon?

The Cameraman, or what’s left of it, is really nice, but totally different from anything Buster had done before,

different in style, construction, humor, characterizations, and in every other way.

Watch it on TV, and it’s not so hot, and, actually, it’s pretty sappy.

Watch it with a thousand other people on the big screen with an orchestra accompanying, and it’s a laff riot.

Its Albuquerque première was at the Pastime in

|

|

As I play the

|

|

Jay Ward’s edition of The General made another appearance

as part of the Buster Keaton Festival at the Lincoln Plaza Cinema in NYC,

|

|

|

|

When I saw the Jay Ward version of The General,

it was not on the same program as the Fields shorts.

It was double billed with Sherlock Jr., the reformatted version with the jazz track.

|

|

Huh?

|

|

I don’t know.

I don’t understand, but I’ll try to do the best I can with my limited knowledge and my faulty memories.

|

|

Per contract, Buster chopped this movie down from six reels to five, each reel lasting about nine minutes.

So Buster’s original preview print was up to about nine minutes longer than the current versions.

Probably it was only about five minutes longer, really.

He shot with two and most likely three cameras side by side,

to create a domestic negative, an export negative, and an emergency backup.

|

|

|

It was probably in about 1937 that MGM sold a lavender to MoMA,

and if people wanted to see the movie, MoMA was the only game in town.

|

|

In 1960, Ray Rohauer borrowed from the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences the nitrate

that James Mason had donated, and he made a dupe negative, but one reel was missing.

In all likelihood, Ray already had another print of the film in his

|

|

Rohauer presented his full collection of Buster flicks at the Venice Film Festival of 1963,

and he called his series “The Golden Years of Buster Keaton.”

This included Sherlock Jr., almost certainly an authentic edition,

|

|

He presented it a few times afterwards,

but by the time he unveiled it at the BFI National Film Theatre in London in January 1968

for a series called “The Films of Buster Keaton,”

he had probably altered the film,

adding spurious titles and making choppy edits.

|

|

It was probably in 1972 that Rohauer assigned Lee Erwin to record an improvised score to the film.

He had the film lab optically reduce the image to the Academy format and mixed in Erwin’s music.

For this edition, the spurious titles were not included,

but it was almost certainly at this time that all the genuine titles were reset and most were rewritten.

This was a

|

|

Then we get to 1975.

|

|

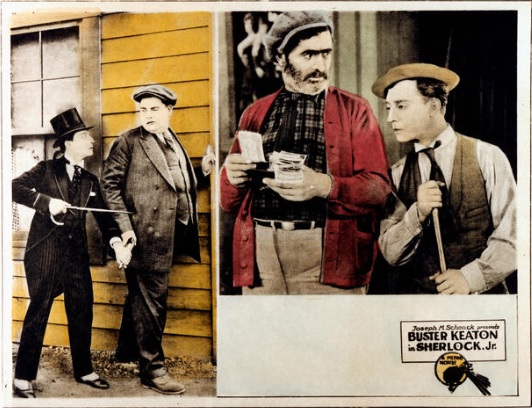

Sherlock Jr. was Bill and Skip’s followup to The General.

Well, I presume it was Bill and Skip who worked on this,

for the simple reason that can be summarized with a rhetorical question:

Who else would have?

They used extremely fine materials (including MoMA’s lavender?).

Well, yes, extremely fine, but there were scratches everywhere.

Not enough scratches to spoil the viewing experience or to compromise one’s enjoyment of the show,

but, yes, there were lots of scratches everywhere.

Still, though, the image was very clear and the detail in the images was remarkable.

The Jay Ward crew instructed the lab to reduce the

|

|

How on earth can we compare the MoMA edition

against Rohauer’s 1963 print and his 1968 print and his 1972 print and Jay Ward’s 1975 edition?

|

|

Well, lo and behold, I just stumbled upon a mention of an episode of “Camera Three” entitled

The Metaphysics of Buster Keaton, a little presentation by Professor Andrew Sarris,

who spent a few minutes allowing Raymond Rohauer to spout a pack of lies.

This was broadcast on Sunday morning, 1 November 1970.

For our purposes, Sarris doesn’t matter,

and for our purposes, Rohauer doesn’t matter.

Please click on that link and take a look at the program.

It includes an excerpt from Rohauer’s 1968 edition of Sherlock Jr.,

cropped, of course, since TV stations were unable to accommodate

|

1968 ROHAUER EDITION Here we have a typical example of the needless titles that Rohauer so commonly added to the movies he released. |

1975 JAY WARD EDITION The original, which did not have any titles here. Note that the top of the image is missing. I don’t think that’s a fault with the film-to-video scan. I think it’s a fault with film print, which was wrongly cropped when it was optically reduced to the Academy format. |

1968 ROHAUER EDITION Note that the action on the inner screen is from a single camera. You will see a jump in the position of the image. That indicates where different fragments of different copies of the movie were pieced together. |

1975 JAY WARD EDITION Note the jump in the perspective, where the camera is suddenly positioned differently. Apparently, for this scene only, the Jay Ward edition starts with Camera A but cuts to Camera B, or the other way around. |

In both of the latter clips, both |

|

|

The

|

|

Here are a few details that will fascinate one person in every 768,431,

and that will make everybody else lose all patience with me and refuse to speak with me ever again.

In common with Jay Ward’s 1975 edition, Rohauer’s 1968 and 1972 editions were missing the opening of the scene

when Buster’s dreamself walked into the auditorium.

That was the scene that opened Reel 3,

and so we can suppose that someone simply shattered the beginning of the reel prior to the new prints being made.

Rohauer’s 1981 edition was missing a trick shot at the billiard table.

Was that also missing in his 1972 edition?

Since both were scored by Lee Erwin, we might think they were identical,

but we learned from the 1972 versus the 1979 edition of The General

that Rohauer did not simply port over Erwin’s score.

He paid Erwin to record a new score.

I suppose the same held true with Sherlock Jr.

Though the 1972 edition and the 1981 edition both sport a score by Erwin,

the likelihood is that Erwin recorded his score anew for the 1981 edition.

So, the 1972 edition could well have included that nice trick billiard shot that was missing from the 1981 edition.

Was that moment also missing from the 1963 and 1968 editions?

I bet it was there, but until I can find the prints or verified copies thereof, I cannot say that with certainty.

I suppose it is included in the MoMA edition, but I really don’t know.

It was in Jay Ward’s 1975 edition,

but Rohauer deleted it by 1977 and remixed the soundtrack to cover the gap.

|

|

Daniel Moews, “Chapter 4: Sherlock Junior: The Fantasizing of Reality,”

Keaton: The Silent Features Close Up

(Berkeley, Los Ángeles, London: University of California Press, 1977), p. 86:

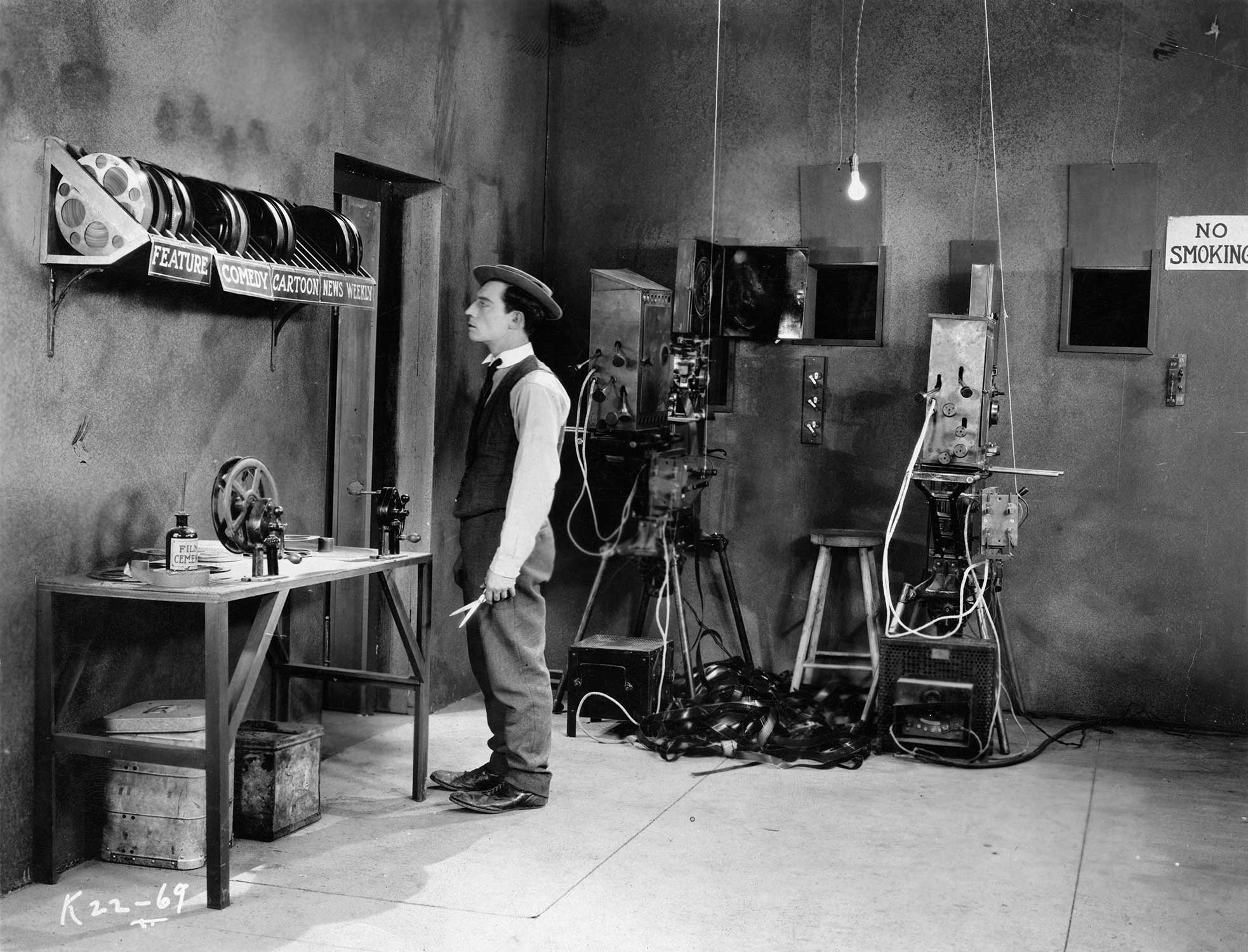

...the boy starts projecting

the afternoon’s film, Hearts and Pearls or The Lounge Lizard’s Lost

Love. Possibly because it is a Veronal Pictures production, Veronal

being a popular but dangerous soporific of the period (two younger

sisters of the novelist Ivy Compton-Burnett committed suicide by

taking overdoses), he soon tires of it and yawns. A title states, “A

projectionist’s job is tedious . . . and the monotony makes him fall

asleep.” Soon, “he dreams.”

|

|

Daniel Moews, “Bibliographical and Filmographical Comments,”

Keaton: The Silent Features Close Up (Berkeley,

Los Ángeles, London: University of California Press, 1977), pp. 327–328:

In a

The criminals having been disposed of with a grenade, Sherlock

Junior and the girl continue to race along in their car. Then she says,

in a title, “Oh, we forgot Gillette. Shouldn’t we go back for him?”

In the Audio-Brandon print, there follows some awkwardly edited

action. In the shot immediately after the title, Sherlock continues to

drive. There is then a cut to a new shot as he approaches a curve and

slams on his brakes. The awkwardness is caused by a visual