Carry on with the Reissues |

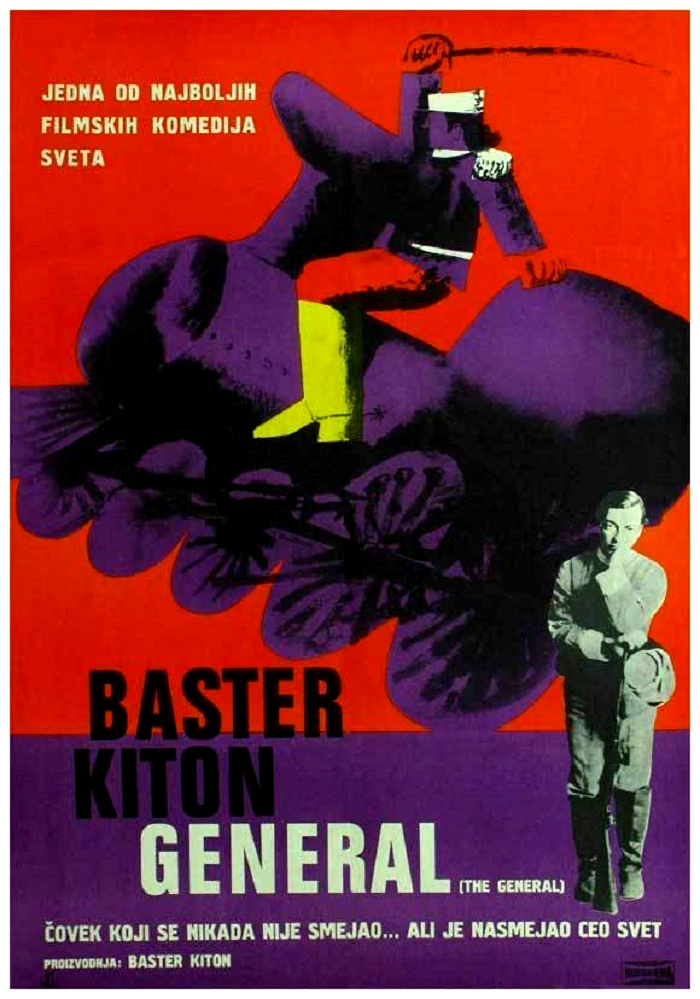

I would hazard a guess that KirchMedia of Germany licensed its version of Der General to a Macedonian company, Makedonija Film of Skopje, but in Croatian for the Croatian-speaking parts of Yugoslavia. Wouldn’t you hazard that guess, too? Click here for the 4½"×6½" program. |

KirchMedia licensed Der General to Constantin-film of Copenhagen. Generalen opened on Monday, 4 June 1962, at the Rialto Teatret in Frederiksberg. The color short subject, The Dog and the Dynamite, sorry, no clue. It was probably included per a prior contract. Click here for the 4½"×6" program. |

|

It [the Rialto] reopens on Monday, 4 June 1962, with Buster Keaton in The General

to commemorate the old silent-film days.

The film was previously known as Krig og kærlighed [War and Love] and Constantin Film is the distributor.

Out front, like in front of Grauman’s Chinese Theater on Hollywood Boulevard in Los Ángeles,

movie stars are supposed to leave their autographs or footprints.

“The place where the stars meet,” it says in front with stars chiseled into the tiles.

It was hoped that Buster Keaton would do the honor of passing by as the first.

Not long before, he had been on a trip to Germany,

where they had found a slightly worn copy of the old film and worked with it in a laboratory,

where new sound and effects had been added to it.

You probably remember how

|

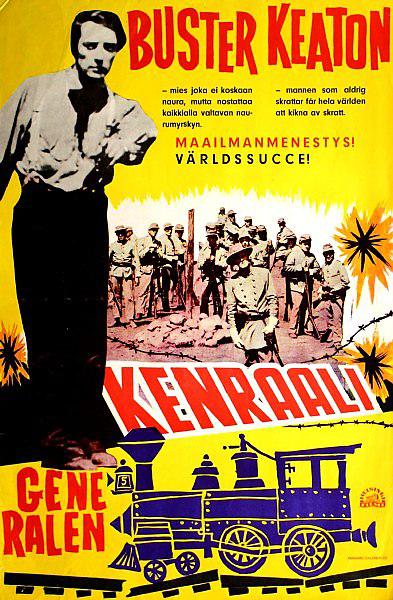

KirchMedia licensed Der General to Helsinki-Filmi in Finland. It supposedly opened on 31 August 1962. For some reason, the poster supplies the title both in Finnish and in Swedish. So, I suppose that the KirchMedia edition was issued in Sweden as well, most likely by Helsinki-Filmi or an associated company across the border. Here’s a nice reminiscence, but maddeningly lacking in details! |

|

The soundtrack that Buster thought he got was not the one he got!

We need to learn more about this. I wonder if his original still exists.

Rohauer, in A Hard Act to Follow,

recalled that Buster absolutely refused to watch The General when it was shown in Munich,

explaining that he never watched his films with audiences.

Yet he had been happy to watch it in 1958 at the Coronet,

he had been thrilled to watch it with students at a university campus, as we learned above.

According to Stan Brakhage, as we saw earlier, and if Stan was telling the truth,

Buster also once attended Steamboat Bill, Jr., with an audience.

|

|

I begin to suspect he attended his own movies with some fair frequency.

Further, as we can discern from the article below, in Germany he would go on stage once the curtains closed

so that he could take his bows.

I suspect that he simply did not want to hear a note of that jazz score with its cartoon sound effects.

It was probably too disheartening for him to bear.

|

|

1963, supposedly early in the year, planned for allegedly 700 bookings.

The title is

|

|

It seems that Towa Pictures Company Ltd of Tokyo subsublicensed Keaton’s Great Train Chase

to N Kikaku Ltd for a 16mm release,

and so N Kikaku Ltd came up with a special chirashi for the 16mm edition.

Did you know that 16mm editions had their own special chirashis?

I didn’t know that.

Did you know that?

I didn’t know that.

The title now has a subtitle:

キートン将軍 (キートンの大列車追跡).

I guess that transliterates to

Kīton Shōgun (Keaton no Dai Ressha Tsuiseki), and it translates as

“General Keaton (Keaton’s Great Train Chase).”

Zo, I just won an example on eBay, and here it is!

|

|

Of course, I know that all of you can read that easily, but I’m illiterate,

and so I had to point my phone’s camera at it and tell Google Translator to read it to me.

And Google Translator read it to me.

And Google Translator was pulling my leg, I’m sure:

|

|

See what I mean?

Except, it wasn’t only Google Translator that was pulling my leg.

The lovely folks at N Kikaku Ltd also had fun in their hobby of

|

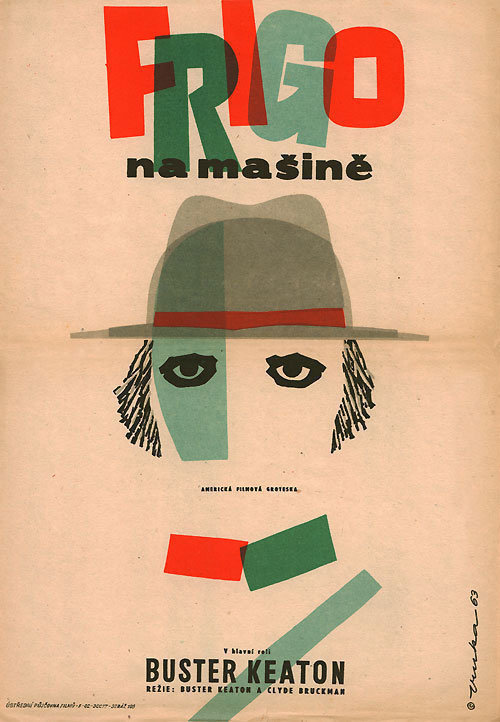

In 1963, KirchMedia licensed Der General to ÚPF (Ústřední půjčovna filmů, or Central Film Rental Company) of Prague. In Czechoslovakia, Buster was known as Frigo, which translates Fridge, and so ÚPF called the film Frigo na mašině (Fridge on the Machine), which I assume was the original The poster was by Vladimir Fuka. |

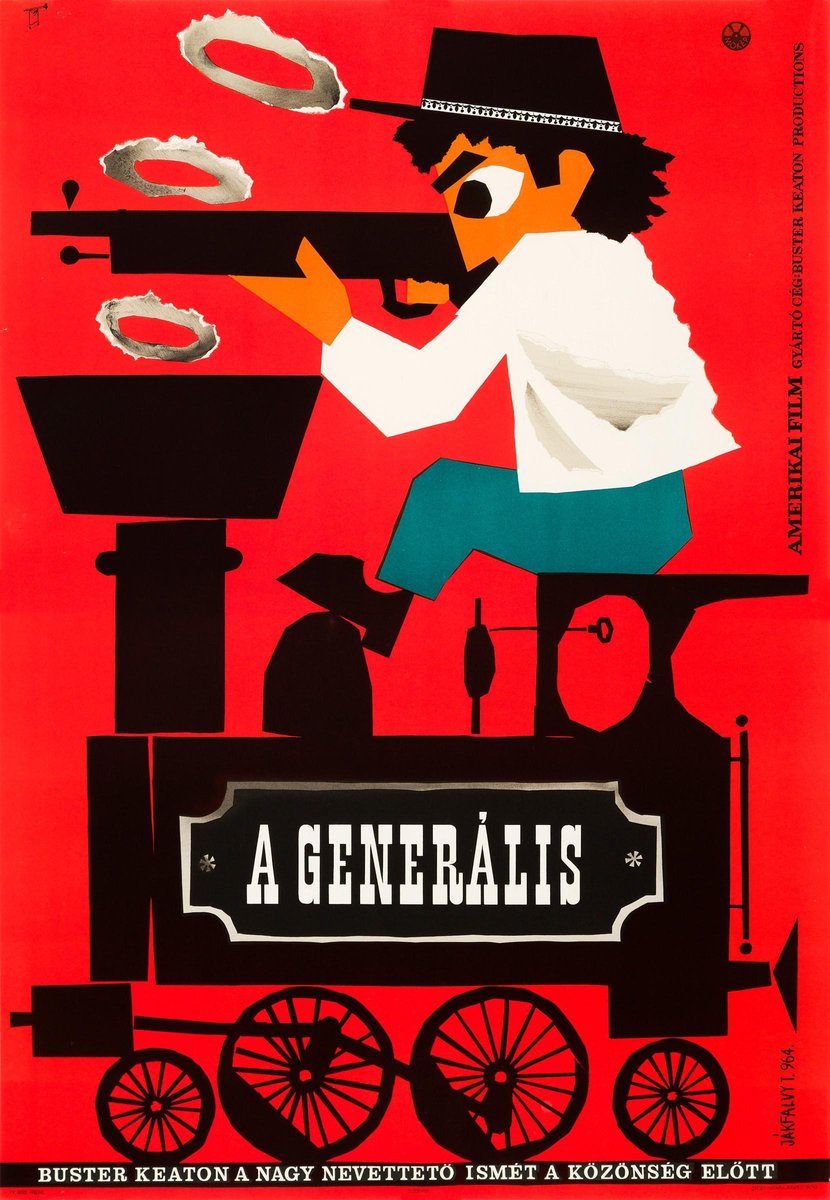

In 1964, KirchMedia licensed Der General to Amerikai Film of Hungary. The poster was designed by Tibor Jákfalvy. |

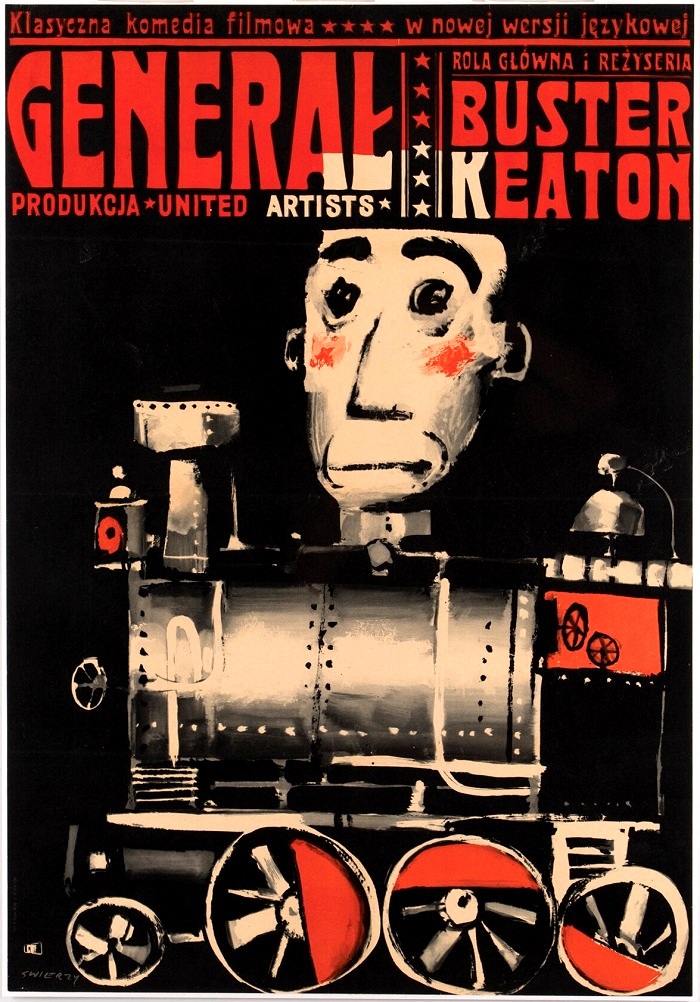

Also in 1964, KirchMedia licensed Der General to CWF (Centrala Wynajmu Filmów, or Film Rental Center) in Poland, which mysteriously insisted on crediting United Artists, which no longer had any legal connection with the film. The poster was designed by Waldemar Świerzy. |

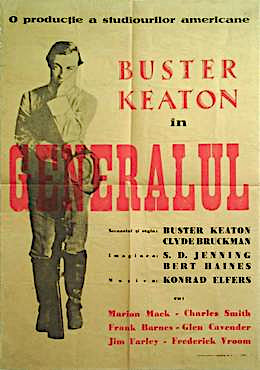

Romanian release. No info. Are you in Romania? Would you like to research this release? If so, please contact me. Thanks! |

|

Below is an article that complicates the issue.

I guess it shifts Masakari.

So, as mentioned above, Atlas also released College, also with a new music score.

That was in the spring of 1963.

Curtis (p. 643) quotes a letter from Rohauer indicating that also on the bill were The Paleface and The Goat.

|

|

Posters found online demonstrate that Atlas also released Go West and Battling Butler.

Where can we find these prints?

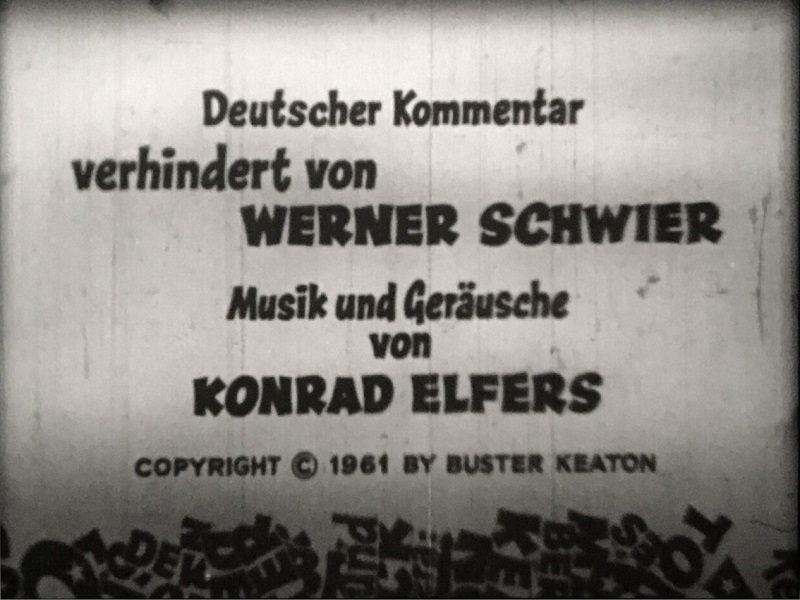

Konrad Elfers

created the soundtracks certainly for

Der Musterschüler (College),

Der Killer von Alabama (Battling Butler),

Der Cowboy (Go West),

Das Bleichgesicht (The Paleface), and

Der Sündenbock (The Goat).

I can only assume he also did

Cops, which was shown together with Der General.

I think that was the entire inventory, but

if there were further Buster releases at the time, then Peter Schirmann would have been the composer.

Most amazingly, KirchMedia licensed The General to a Soviet distributor!!!!!

And the distributor PAID ROYALTIES, even though the USSR still did not have any copyright treaties with foreign governments.

Altogether, this boggles my mind.

Or it minds my boggle.

If you have any information, any information at all, about the Soviet reissue of 1963,

please let me know. Thanks!

|

|

Well, if the unnamed Soviet distributor licensed the movie,

something went wrong, because it turns out that it was never shown in the Soviet Union.

|

|

There are indications that The General also came out in Portugal in May 1965.

I have no particulars.

|

|

Here is another version of the story:

|

|

Keith Scott, The Moose That Roared: The Story of Jay Ward, Bill Scott, a Flying Squirrel, and a Talking Moose

(NY: St. Martin’s Press, November 2001), p. 227:

Rohauer, an ardent

Keaton admirer, helped the down-on-his-luck comedian restore his decomposing

nitrate films; then he formed a corporation through which Keaton

could regain control of these films, which until then were tied up with

the Joseph Schenck family. Over the next decade Rohauer arranged enormously

successful in-person screenings of Keaton’s masterpieces in Europe.

|

|

The KirchMedia edition of The General was scheduled for release in the UK in early 1963, and plans were to get it

900 bookings.

What went wrong, I cannot even imagine.

It opened in England in probably in September 1963, though the earliest adverts I can find date from

November 1963.

It was distributed by a firm called Regal Films International, Ltd.

No ballyhoo.

No publicity.

No news stories.

No nuthin.

Just dumped here and there on occasion, usually as the second bill to a new film;

thus did film suffer outstanding injury being swallowed by muddy water.

Perhaps KirchMedia put Der General up for bids in the UK,

and this lousy Regal deal was the best offer?

Something went terribly wrong, and I’m totally confused.

|

|

This is Regal’s quad, reproduced here courtesy of

OriginalPoster.co.uk.

No date is printed, unfortunately.

The artist’s signature, by the cannon’s wheels, reads merely “g.h.”

Might anybody know who this g.h. was???

Click here to see the pressbook, which confirms that this is indeed the KirchMedia edition with the Konrad Elfers soundtrack.

You can’t read that final line at the bottom right, can you?

|

|

|

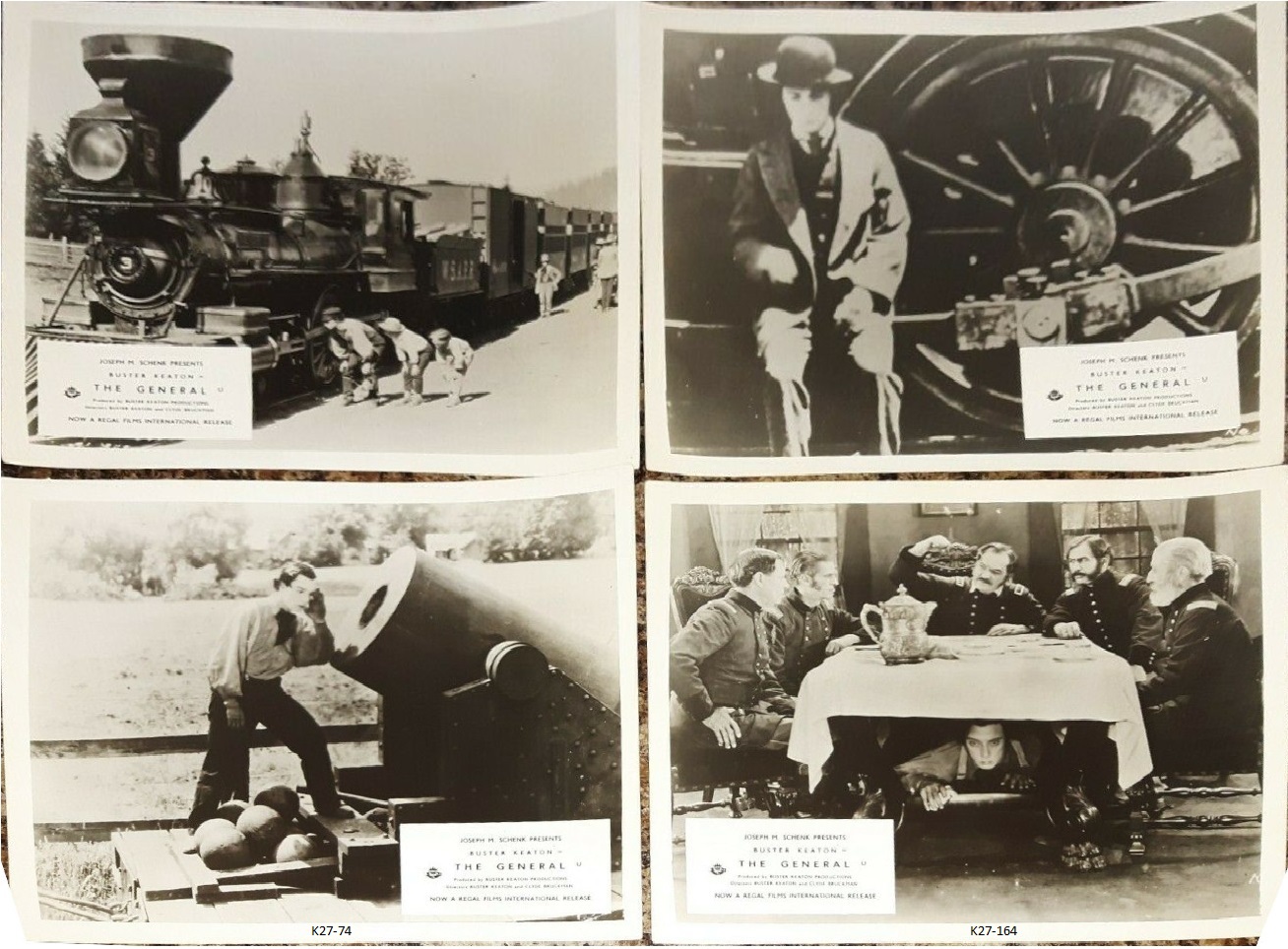

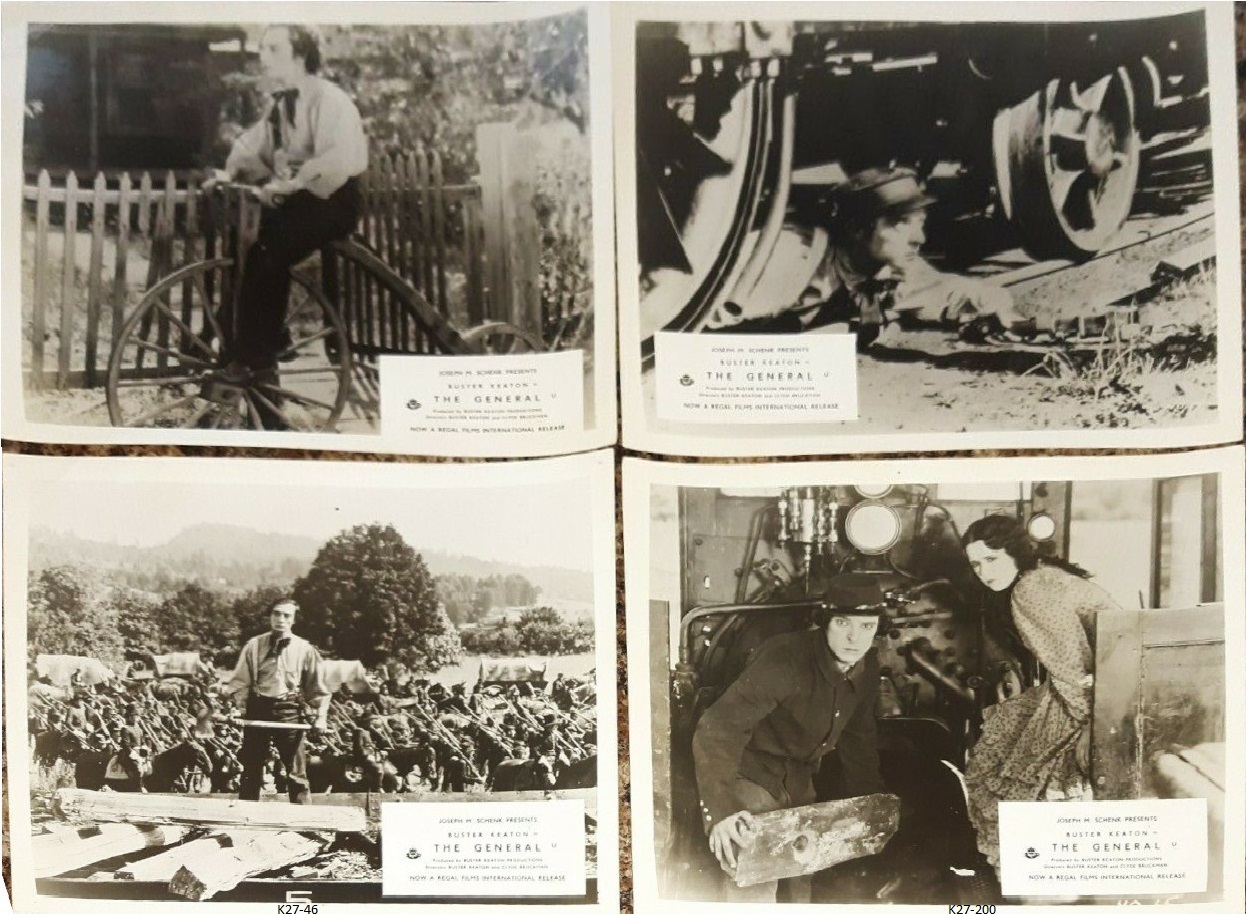

Just saw these on eBay. Will not ship to the US, alas:

Zo, whaddayuh do when the vendor won’t ship outside of England? Why, you purchase an English address from ForwardVia, that’s what. It took a month and a half to reach me, but hey, it reached me! Here’s the set. |

“This is pure comedy, lacking the satiric implications of Chaplin’s work

with its viewpoint of oppressed individuality and mass insanity”?????

HUH?????

That’s there. It’s all there.

Charlie was a propagandist and he liked to hammer you over the head with it.

Buster preferred to take society as an absurdist given and leave it to the audiences to see in the story whatever they chose.

I guess some audiences either prefer not to notice or are not able to notice.

As for retaining “the original titles with their occasional spelling errors,”

the titles were all replacements, poor ones.

There were no spelling errors in the originals.

|

|

According to

Variety (5 September 2001), Regal Films International was founded in 1958 by

Michael L. Green (formerly of United Artists) and

Joe Vegoda (formerly of RKO).

The

head office was at

Nascreno House, 27/28 Soho Square, London W1 (tel. GERard 9372).

The firm was bought out by

British Lion in 1963, and that means that this Regal release might actually be a British Lion release.

IMDb

indicates that the Regal Films International name continued in use through 1965.

According to Anthony Gruner,

“London Report,”

Boxoffice, 1 November 1965,

|

|

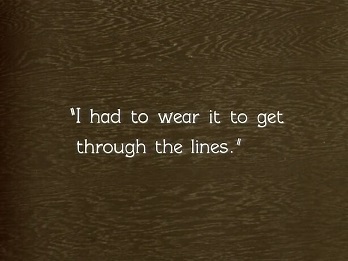

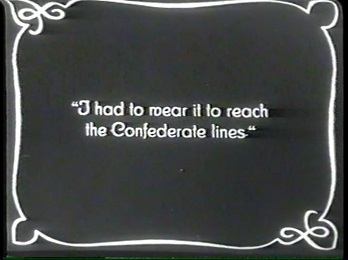

My guess is that KirchMedia did not ship copy negatives to the distributors of the above European and Japanese releases,

but sent each of them a handful of prints.

The title cards were messed up.

Here, let’s let Buster explain

(John Gillett and James Blue, “Keaton at Venice,” Sight and Sound vol. 35 no. 1, Winter 1965–1966, pp. 26–30,

reprinted in Kevin W. Sweeney, Buster Keaton Interviews, Jackson: University Press of Mississippi, 2007, pp. 220–221):

|

|

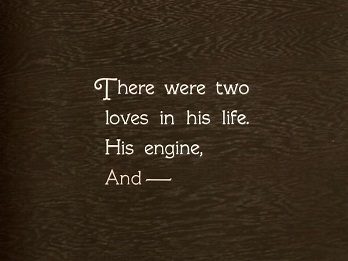

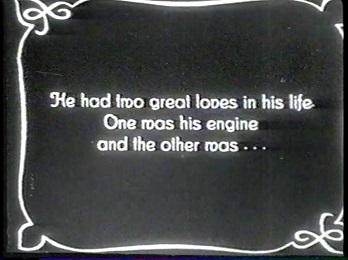

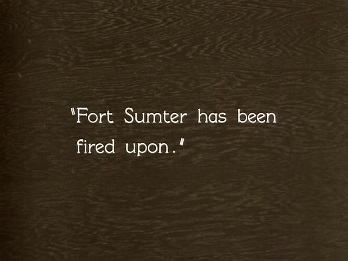

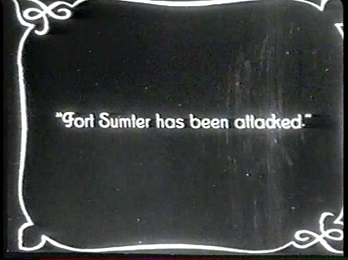

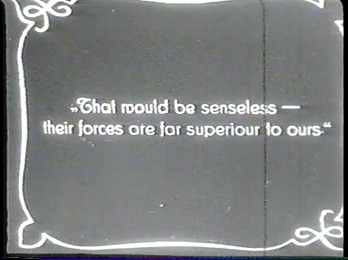

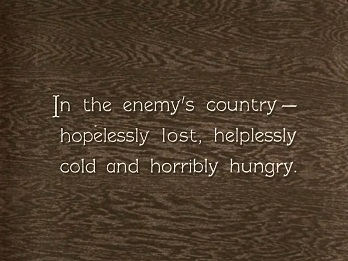

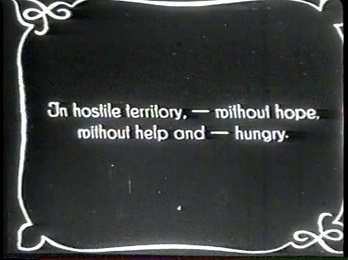

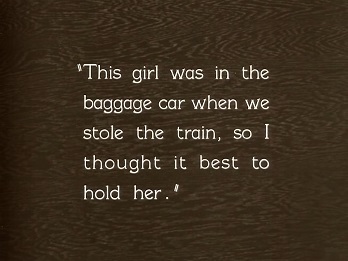

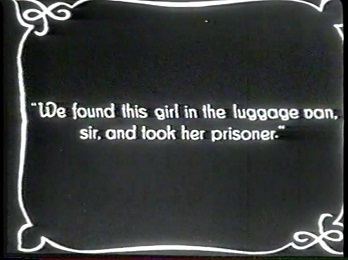

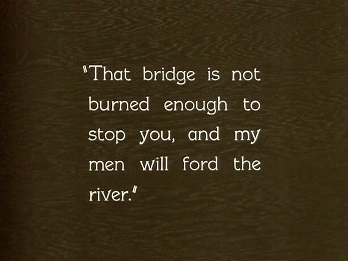

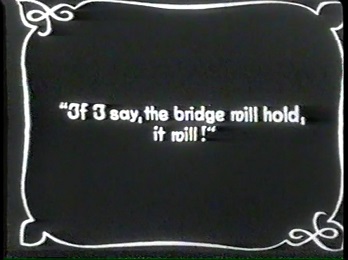

BUSTER KEATON: I ought to do something about the new release print

of The General that was shown in London. When the film was to be

revived in Europe we brought over as many old prints as we could find,

in order to pick out the best reels — to find the ones that hadn’t faded, or

been chewed up by the machine. We gave them to the outfit in Munich

who were handling the film, and they made a duped negative. They did a

beautiful job of it. The first thing they wanted to do, as an experiment,

was to translate all the English titles in German so that they could release

the film in Germany. It did a beautiful business there, so immediately

they made some more prints with French titles for release in France. Now

they must have lost the original list of English titles, so they put them

back again into English from their own German translation.

I happened to see a print of this new English version in Rome last

week — the same version you had in London — and the titles were misleading.

For instance, when I’m trying to enlist and I’m asked, “What is

your occupation?” I say, “bartender.” Well, that type of man gets

drafted into the army immediately. In the new version the title reads

“barkeep” — that means you own the place. And it doesn’t sound as

funny anyway in English: it might in German, I don’t know. Then they

put “sir” on to the ends of sentences because I’m talking to an officer,

but there’s no “sirring” at all in our titles. Some of the explanatory titles

were changed or chopped as well. Do you remember, for instance, the

scene where we all got off the train and while we were away the engine

was stolen? We actually stopped off there for lunch: the conductor

comes into the car and says “This is Marietta: one hour for lunch.” But

they left that title off, and without it you’d think the train had emptied

out because it was the end of the run. In which case there’s no reason

to steal the engine then: they could have waited until everyone had

gone and the place was deserted.

|

|

If that title was missing from the British print,

then it was certainly missing from all the other KirchMedia prints as well. Egad.

|

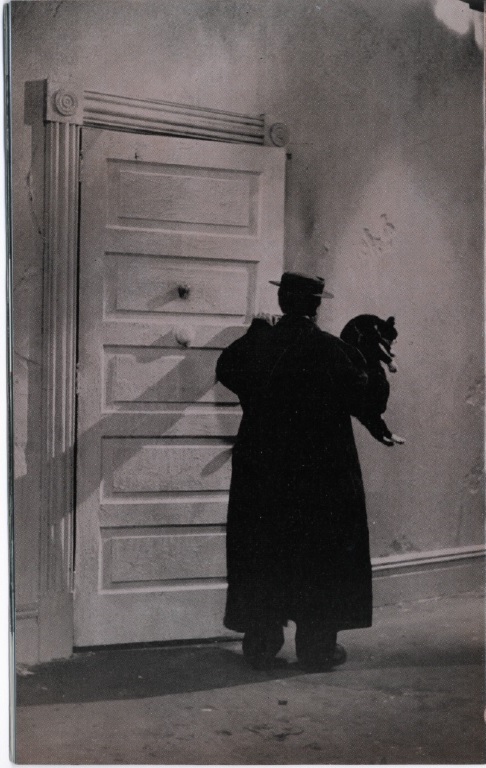

K27-40, K27-97, K27-110 (twice) Publicity portrait by Melbourne Spurr, Hollywood |

|

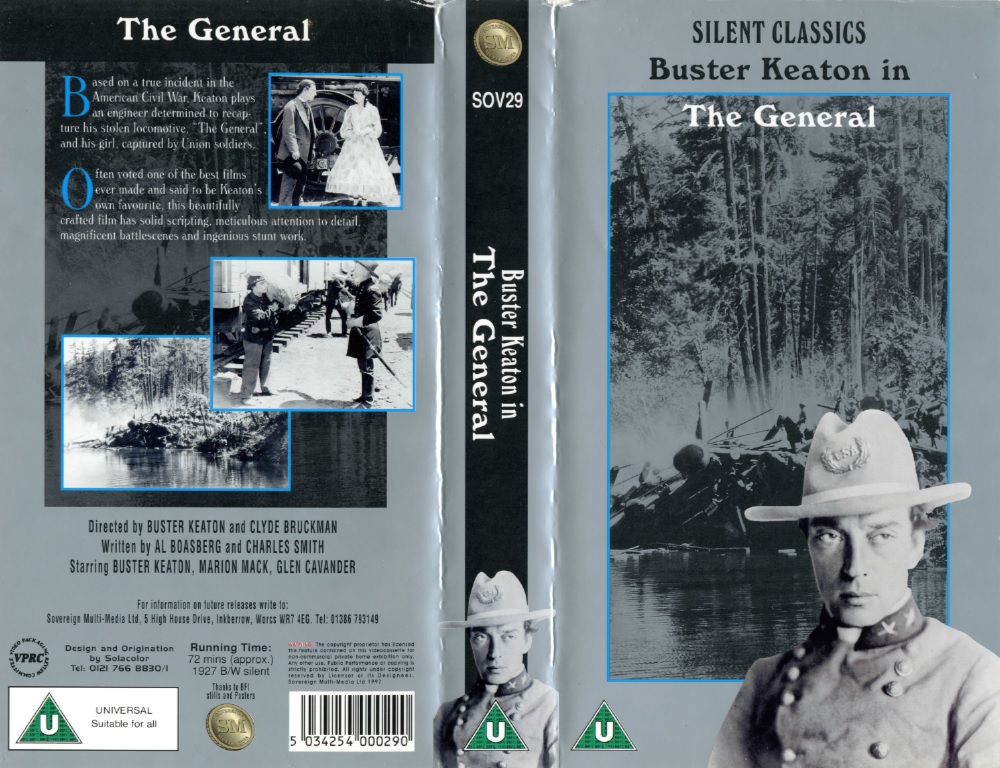

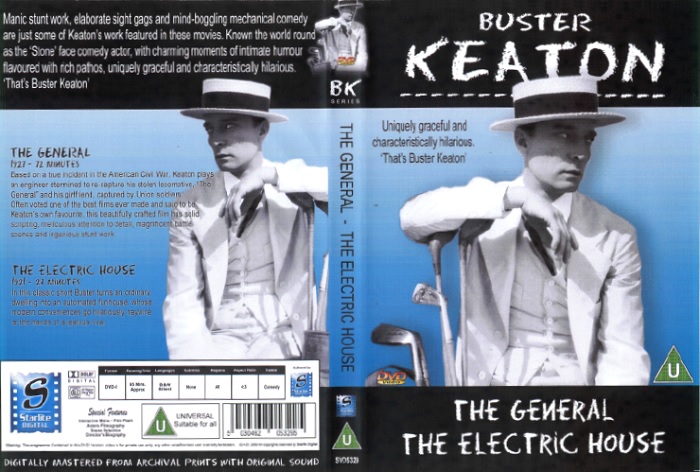

The Regal edition was issued on home video in 1997.

Though this is definitely the Regal edition, the Regal name appears nowhere.

The tape’s distributor, Sovereign

Initially, I was dumbstruck that this horrid version had ever found an audience,

but my opinion changed over the next few days, and changed quite drastically.

I cannot know, but I suppose that some of this music was Buster-approved,

and that some of it was replaced by order of either KirchMedia or of Atlas Film.

I drew out a chart. See if you agree:

Konrad Elfers was a marvelously talented composer, but much of his score

had nothing to do with the movie.

About half of the cues

are splendid and fit the mood, action, and meaning flawlessly.

The final two cues, for the final two scenes, are beyond perfect; they are superlative.

Unfortunately, this particular online video chops the ending off, which kills the musical argument.

The other half of the music is entirely

inappropriate.

It’s nice as music that a band might wish to play at a nightclub,

but it doesn’t fit the scenes in this movie at all.

For instance, in the scene

when Annabelle is sobbing as she is being held prisoner,

the accompanying sound is a cheerful lounge tune.

The sound effects are what one would expect in a cheap TV cartoon.

The inappropriate music added to the inappropriate sound effects diminishes the film, belittles the film.

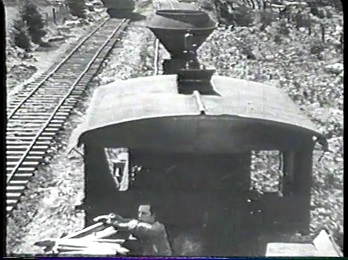

The video transfer, especially on VHS, by the way, is terrible — it’s blurry, much of it is terribly dark,

and all of it is cropped.

Courtesy of a colleague, I now have some frame grabs from

a German 16mm print of the Atlas edition.

Horror of horrors!

I did a somewhat clumsy overlay, with the 16mm image,

pasting over the nearly full image as seen on the Kino K669

Egad!!!!! |

|

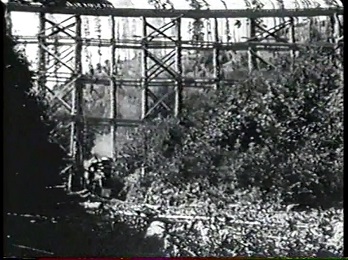

When a title tells us that we are at the Rock River Bridge, the image is so dark that

the bridge is almost invisible.

The opening shot of Reel 5 is missing; but that is only because

the video derived from a print that had been shattered.

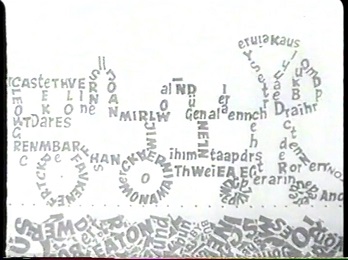

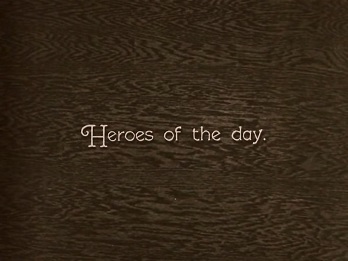

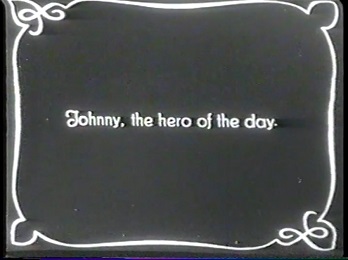

The opening titles are animated in the style of kiddie TV shows.

This was standard practice with Atlas Films reissues.

Did you click on that link to

the opening titles?

Click on it.

Listen carefully.

The music tape was cut.

Several measures were snipped out.

Elfers scored the animated German titles,

which included a disclaimer that there would be no narration as per orders of Werner Schwier.

|

|

|

That made no sense outside of Germany, and so that title was snipped out,

resulting in a snip in the music.

As for the remaining titles, the translations back into English were made by a German whose English was quite hesitant.

The titles are terribly awkward and they are filled with typos, but there are only two instances of “sir.”

Also, it was not “barkeep,” but “barkeeper,” which isn’t quite as bad, though it ruins the joke all the same.

Altogether, on a first viewing, and even on a second viewing, I was simply horrified by the Regal edition

and I saw it as an example of how not to present a silent film.

I fully understood why Buster did not want to watch a frame of this with an audience; it would have been too humiliating.

Yet this KirchMedia edition with the Elfers score was amazingly popular in continental Europe and presumably in Japan as well,

and it surely earned Buster some impressive royalties. So hey.

What’s more, I have now seen it several times,

and after the initial shock wore off, I came to understand how some people would enjoy this.

|

|

Second thoughts:

I burned a

|

|

Shall we take a quick look?

Here are some screen grabs of the Kino K669

|

| Kino K669 Blu-ray | Regal Sovereign SOV29 VHS |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Oh my heavens!

It just now hits me, from out of nowhere.

I wasn’t even thinking about it when it struck me.

I know why the 16mm prints are such a disastrous mess.

The 35mm release prints for Germany, France, Japan, England, and so forth,

were cropped from Ray Rohauer’s dupe negative.

The cropping was the usual lopping off of the left side.

The English titles were removed and replaced with black slugs so that they could be substituted, via

The 16mm prints were made from a new 16mm dupe neg of a cropped 35mm dupe neg of Rohauer’s full-aperture dupe neg.

While making the new 16mm dupe neg, though, the technicians ran it misframed,

lopping off the top of the image much more than the bottom.

The titles were again inserted via

|

|

This exact same transfer is also available on DVD, as I discovered to my surprise.

This DVD:

|

Starlite Digital SVD5329 from Stonevision Entertainment, 2009. |

|

When I received this Stonevision DVD, I spot-checked it and determined that it was identical to the Sovereign VHS.

So I put it on the shelf and forgot about it.

Bad move.

I should have studied it.

We can see something in the DVD that is not apparent in the VHS;

namely, the source print was 16mm!

According to Andy Benz, Atlas was notorious for issuing 16mm prints of terribly inferior quality.

|

|

There must have been at least two prints for each territory:

West Germany, Croatia, Denmark, France, Belgium, Spain, Finland, Sweden (probably),

Japan, Czechoslovakia, Hungary, Poland, Romania, Portugal, and the UK.

So there were at least 28 or 30 prints,

together with a copy negative, a copy negative of the audio-mix submaster, and

|

|

Were there KirchMedia reissues in Ireland, Iceland, Greenland, Norway, Luxembourg, Switzerland, Austria,

East Germany, the rest of Yugoslavia, Greece, Bulgaria, Albania, Turkey, Australia, New Zealand,

Hong Kong, or elsewhere?

Does anybody know?

|

|

When Atlas Filmverleih GmbH temporarily shuttered in 1966,

its rights reverted to KirchMedia,

and it appears that in the early 1970’s, KirchMedia brokered a deal with Neue Filmkunst Walter Kirchner

to revive the European releases.

The poster art was carried over, and the prints, with the Elfers score, were sourced from the same masters.

Here are some press materials.

The story gets vague, but it appears that Kirchner soon shuttered as well,

and that Rohauer himself took over German and perhaps Euro/Japanese distribution.

Apparently, this KirchMedia/Elfers edition was broadcast on German television several times,

I presume in the 1970’s and 1980’s.

If you recorded it and still have the tape,

please let me know.

Thanks!

|

|

Misremembering

So, as we can see, The General was pretty much forgotten except by

|

Harvey Cort and The Great Chase |

|

Paul Killiam recycled his 25-minute “Silents Please” abridgment for inclusion in

Harvey Cort’s feature film,

The Great Chase.

This anthology was ready by

April 1961 but was not seen until a year later at the

Seattle World’s Fair Playhouse for the

Century 21 Exposition.

|

|

For no reason I have ever been able to comprehend,

one of the sequences in this anthology was not from the US and was not a chase and was not silent.

It was staged “documentary” footage shot in the Amazon by Franz and Edgar Eichhorn,

and if you have never had a nightmare, brace yourself.

The Eichhorn brothers sold their footage to Ufa, which, in 1938, built a fictional film around it.

That film was called Kautschuk (Rubber),

but The Great Chase did not reveal that title, and instead said the excerpt was from something called Jungle Treasure.

If you are prepared to steel yourself against the terror, you can watch Kautschuk, without subtitles, on

YouTube.

|

|

Few cinemas advertised in the NYT at the time, and so we know about its NYC première on Thursday, 20 December 1962,

at the

Embassy 46th Street Theater and at the

72nd Street Playhouse only because of

the gripe published the next day.

The film was narrated again by the great Frank Gallop.

I’m not absolutely certain, but I think 35mm prints of The Great Chase were optically reduced to fit onto 1:1.85 screens.

You see, the Embassy Home Entertainment VHS copy that I purchased circa 1985

was transferred from a heavily windowboxed print of the film.

|

|

As we saw above, Buster occasionally said he would not release his films to cinemas in the US,

in part because he had not been able to clear all the rights.

At another time, he said he planned to clear those rights.

Now the team of Cort-Turrell-Killiam usurped a chunk of that market with this anthology.

It is difficult not to wonder if that was precisely the reason for this film.

After all, The Great Chase was ready for release by April 1961,

a year after KirchMedia contacted Buster about a European release.

If Cort-Turrell-Killiam were privy to that news,

then it would have been all too easy for them to cut the “Silents Please” edition into The Great Chase.

The edit could have been done in less than an hour

and the music could have been composed and synchronized to the image probably within a week.

This could all have been coincidence, but I suspect it was competition.

For reasons unknown, the première of The Great Chase was delayed by a year.

|

What about Italy? |

|

Italy at the time had an unusually rich film culture and would surely have gone wild over The General.

Did KirchMedia Film not offer it to Italy?

Perhaps not.

My imagination: Ray Rohauer requests KirchMedia not to deal with the Italian territory, because he has his own plans for the country.

Is that a good guess?

I don’t know.

It could also have been that KirchMedia had attempted to license the rights to Italy, but ran up against the usual Italian brick wall.

Is that a good guess?

I don’t know.

What we do know is that something special happened in Italy

|

|

Despite this marvelous showcase,

it seems that Buster’s movies were not put back into general release in Italy.

So, it looks like Italy did not target Suki, and did not run through snow with Kasumi.

I could be wrong about that, but so far I see no indications otherwise.

Buster told gossip columnist Hedda Hopper that

“The General will be releasing in Rome about the time I get there.”

He said that circa

7 September 1962, and he was scheduled to sail on the

Leonardo

circa 22 September 1962.

So, we can conclude that The General was scheduled to open in Rome at the end of September

or maybe at the beginning of October.

I have yet to find any evidence that it actually did.

I’ll keep looking.

|

Back to Rohauer |

|

I don’t know the full story, which is probably forever buried,

but I do know that when Rohauer was informed that Buster had just passed away,

Ray, instead of expressing grief or sorrow, harshly asked,

“Is it confirmed?”

Had he been waiting for that moment to lay total claim to Buster’s output?

|

|

As Ray continued to find prints here, there, and elsewhere,

and as he legally laid claim or legalistically bullied claim to their ownership,

he began exhibiting the films.

For instance, there was an “Homage” series of four matinées beginning on 1 October 1966

presented by the Exceptional Film Society at the Philadelphia Museum of Art.

Other such presentations were given, but I do not have all the details.

What we know for certain is that Ray had bigger plans to get Lotus Army behind him to run through snow with Kasumi.

|

|

Ray continued to present Buster’s movies here and there.

Here are the few screenings I’ve been able to trace:

|

|

Ottawa Film Festival,

The International Film Festival of Laughter, at the Somerset Theatre, 7 April 1967: The General.

|

|

I moved to Buffalo twenty years later,

but everyone was still talking about this series as though it were current and as though I already knew all about it.

In 1988 or 1989, I met Maynard “Skip” Pettit and I tried to pick his brains about silent movies.

I was curious about any ideas he might have about how to add speed controls to modern projectors.

He looked confused.

He said he had been the projectionist for the silent series at the Buffalo Museum of Science, and the films looked fine,

“nobody was running anywhere.”

He didn’t know what on earth I was worrying about.

What Skip hadn’t realized was that the speed controls had already been turned down for some of those films.

Then I had some dealings with

Frontier Amusement Corporation, and a booking agent there,

Chuck Van Dusen, proved to be a silent buff and a Buster fan.

He started telling me stories about this Ray Rohauer guy, because he had first dealt with him

when he was involved in the silent series at the Buffalo Museum of Science.

Over the phone, he once said, “He had the personality of an amoeba.”

In a letter, he continued, saying that Ray was like the little girl with the curl.

When he was good, he was very good indeed, but when he was bad, he was horrid.

Chuck was still upset that the print of

Becky Sharp that Ray had shipped to them had the worst color he had ever seen.

It was a tremendous embarrassment, a shaming experience, since the guest of honor that night was the film’s director,

Rouben Mamoulian.

Then sometime around 1995, I was introduced to

Charlie Stein.

I was deeply impressed by him, and he was deeply impressed by me,

because we were both familiar with a father-and-son architect team named Leon Lempert Senior and Junior.

Not common knowledge, to say the least.

So he regaled me with many stories.

To my surprise, he told me that he had been the one who got the silent series started at the Buffalo Museum of Science.

He had been in charge of it, together with Albert B. Feirman, whom I never met, Dave Mix, whom I never met, and Chuck Van Dusen.

They established a 501(c)(3) called Silent Movies, Inc., and they began hunting for a good screening room,

which they soon found at the Buffalo Museum of Science.

They hired a pair of organists,

Art Melgier and Ed Bebko, Sr. (“Eddie Baker”), who took turns, each playing on different nights.

Later they added a third,

Nelson E. Selby,

and when Nelson died, they hired Harvey Elsaesser.

As for the organ, I can no longer recall any specifics,

but I presume is was a rented electric organ, probably an Allen, which kinda sorta synthesized the sound of a real theatre organ.

They hired a pair of

Ampro 16mm projectors with carbon arc and speed controls.

There was a dial on each machine with five settings: 16fps, 18fps, 20fps, 22fps, and 24fps.

Charlie would set the speed himself.

Charlie started telling me about Raymond Rohauer, and everything he said surprised me,

because I had no idea that he had ever even heard the name.

Oh yes, he sure had.

Now, Charlie had not seen or even heard of The General until shortly before he began his series.

Where, how, and when he saw it, I do not know.

He was impressed and wanted to open his series with it.

That is when he was warned that in order to book the movie,

he would need to deal with a most troublesome chap named Raymond Rohauer.

Charlie called Rohauer on the phone, and Rohauer immediately began shouting at him, chewing him out, telling him off,

and finally he barked, “Who are you anyway?”

Charlie barked back, “I’m Dr. Charles W. Stein from Buffalo, and...”

and as soon as he said that, Ray stopped him and in the friendliest, warmest tone of voice possible, expressed his joy:

“You’re from Buffalo? Why didn’t you say so? That’s my home town!”

So, only because of the Buffalo connection, Ray agreed to book the film, but he insisted upon two conditions.

First, the programmers would have to pay him a public tribute at the screening.

Second, he would carry the 16mm print in himself, and it would never leave his side.

Charlie was rather disbelieving, but okay, if that’s what it took, he would agree.

So Ray showed up, the film series began with a public tribute to him,

and Ray then walked the print to the booth and sat right by the machines

and would not let the film out of his sight the whole evening.

Charlie began to get an idea about what was bothering Ray.

He went to the booth and explained,

“We’re not going to copy it.

The only film lab in the area is” and I can’t remember what it was, but he continued,

“and they only work for the TV news and sports teams and they won’t accept orders from anyone else.

So nobody’s going to copy your movie.”

Ray looked suspicious and still would not let the print out of his sight.

When the movie was over, Ray packed it up and took it away.

Anyway, Ray was really impressed that nobody had expressed even the vaguest desire to snatch the movie from him,

and so he agreed to rent Charlie any movies he wanted.

Sixteen years did I reside in Booffalo,

and though I kept telling myself I would visit the Museum of Science, I never did, and I regret that.

After having been away from Booffalo for a decade or so, I began to collect my thoughts.

That is when I vowed never to set foot in Buffalo or any part of Western New York ever again.

Some people there were exceptionally nice,

but there were more than enough stinkers to ruin the whole experience forever.

Hatred, corruption, racism, violence, enforced poverty, and sadistic police are ubiquitous.

You’ll find them wherever you go.

Booffalo & WNY, though, had a few extra degrees of it that I never experienced anywhere else.

In normal life, you never really know what others think of you until you’re in trouble,

and that’s when you sorta wish you had never found out.

During my last few years in Booffalo, I knew exactly what people thought of me:

From the moment they first laid eyes on me, they all wanted me dead.

I was truly in love with that city.

I was in love with the whole of Western New York and the Southern Tier, really.

Now the very thought of the place gives me an upset stomach.

Oh. One more thing.

Charlie had never heard of Buster Keaton until sometime in the 1950’s or 1960’s.

Though he had grown up in a movie family and went to the movies constantly in the 1920’s,

he had never once heard the name Buster Keaton and he had certainly never seen Buster’s movies.

When he finally did learn about Buster (perhaps through his research into vaudeville),

he asked friends his age who had also been movie buffs back in the 1920’s,

“Did you ever hear of Buster Keaton?”

Without exception, everybody answered, “No, never heard of him until recently.”

Bizarre. Totally bizarre.

I checked the 1920’s newspaper listings, and Buster’s movies all played at the biggest Buffalo cinemas,

prominently, and came back for second and third runs for months afterwards.

His films received large display ads,

and how Charlie and his friends managed to miss every last one of them, I shall never know.

I see from looking at the schedules that Charlie booked lots of Buster’s movies from Ray,

and, now that I can piece this info together with my memories of the stories he had told me,

I can figure out what happened.

Charlie Stein worshipped at the feet of Charlie Chaplin.

As he watched the Buster movies come in, one by one over the nine years of his series, he was disappointed.

Buster just didn’t resonate that much with him.

He said Buster’s movies are all the same:

A pathetic weakling inexplicably gains heroic strength and wins the girl. Ho hum.

Charlie told me that he really liked two of Buster’s movies, though:

Our Hospitality and The General. Good choices. Those are the best ones.

These three stories, from Skip circa 1989, from Chuck circa 1990, and from Charlie circa 1995,

are all from memory, and so I might be mucking the details up a bit, but the basics are all correct.

Why do I publish these stories?

Because if I don’t write them down, nobody will write them down,

and they will be forgotten, but they deserve to be recorded.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Silent Movies, Inc., is founded, The Buffalo Evening News vol. 174 no. 67, Season 1, The Buffalo Evening News vol. 174 no. 123, Season 2, The Buffalo Evening News vol. 177 no. 4, Season 3, The Buffalo Evening News vol. 178 no. 130, Rohauer, The Buffalo Evening News vol. 179 no. 100, Season 4, The Buffalo Evening News vol. 180 no. 130, Season 5, The Buffalo Evening News vol. 182 no. 140, Ed Bebko, The Buffalo Evening News vol. 182 no. 140, Season 6, The Buffalo Evening News vol. 184 no. 139, Season 7, The Buffalo Evening News vol. 186 no. 148, Season 8, The Buffalo Evening News vol. 188 no. 141, Season 9, The Buffalo Evening News vol. 190 no. 143, Feirman obit, The Buffalo Evening News vol. 193 no. 17, Charlie’s award, The Buffalo Evening News vol. 194 no. 16, |

|

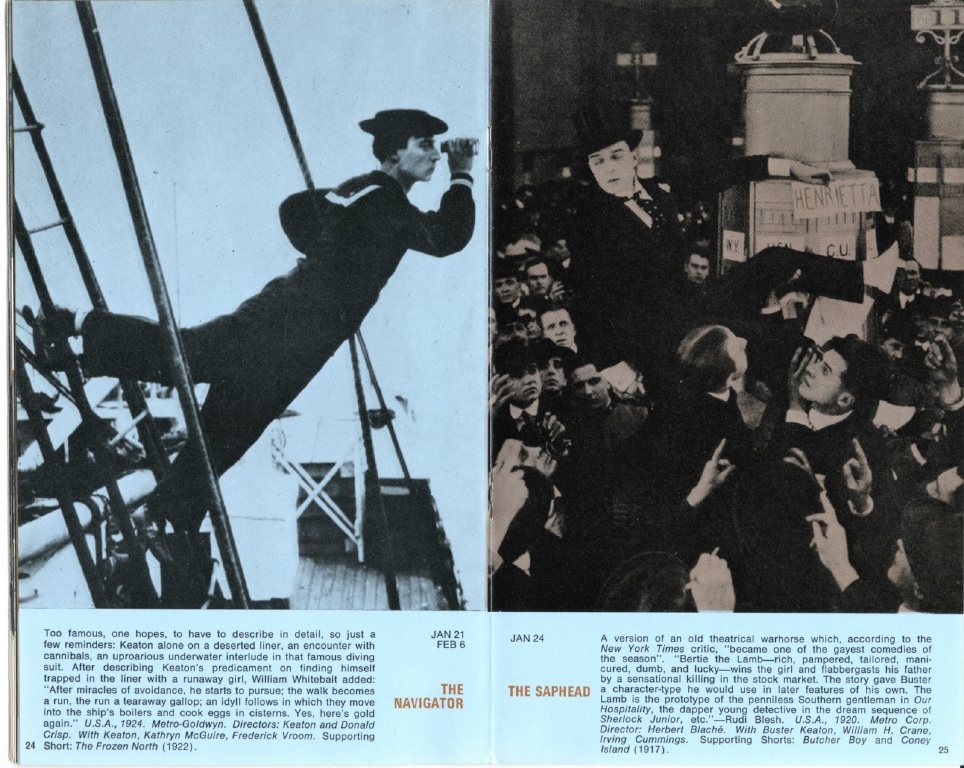

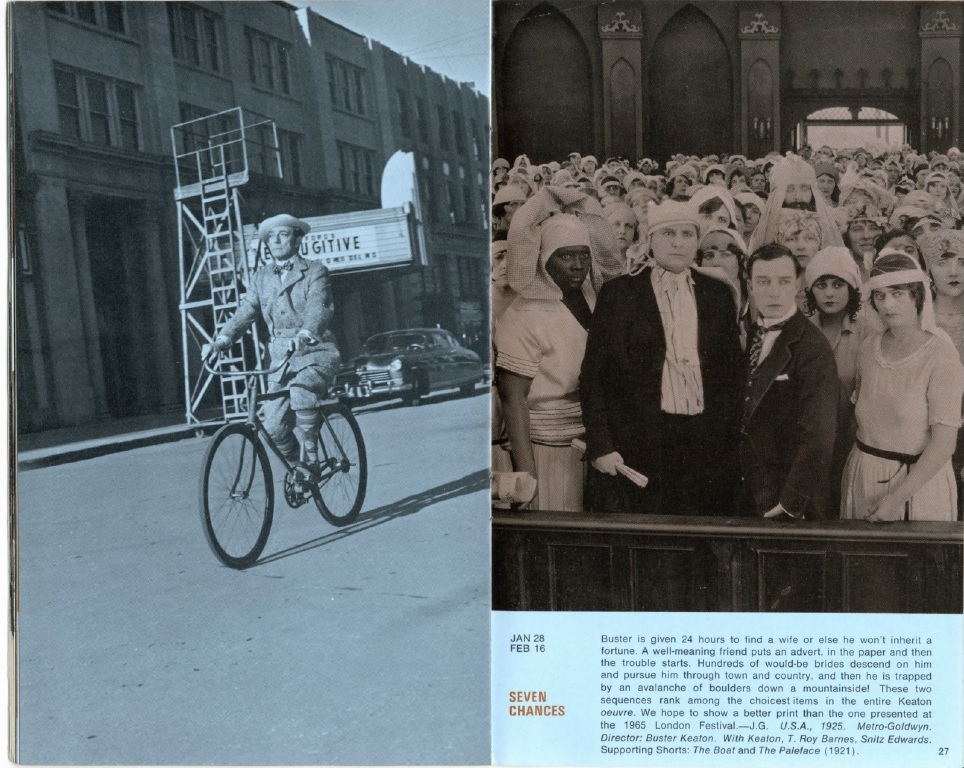

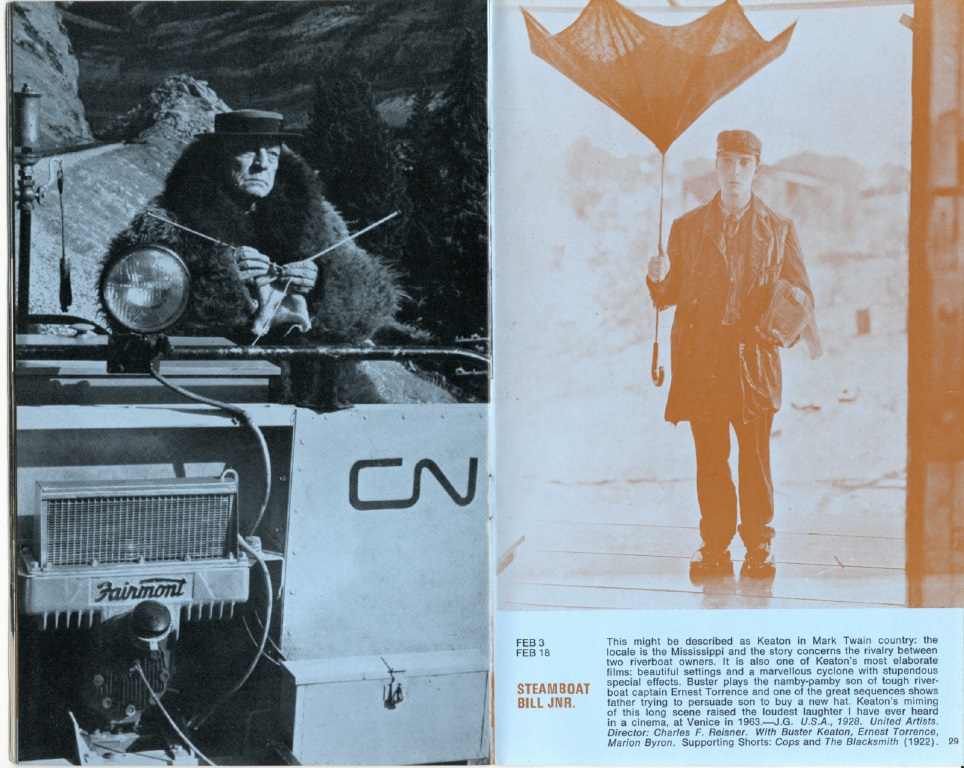

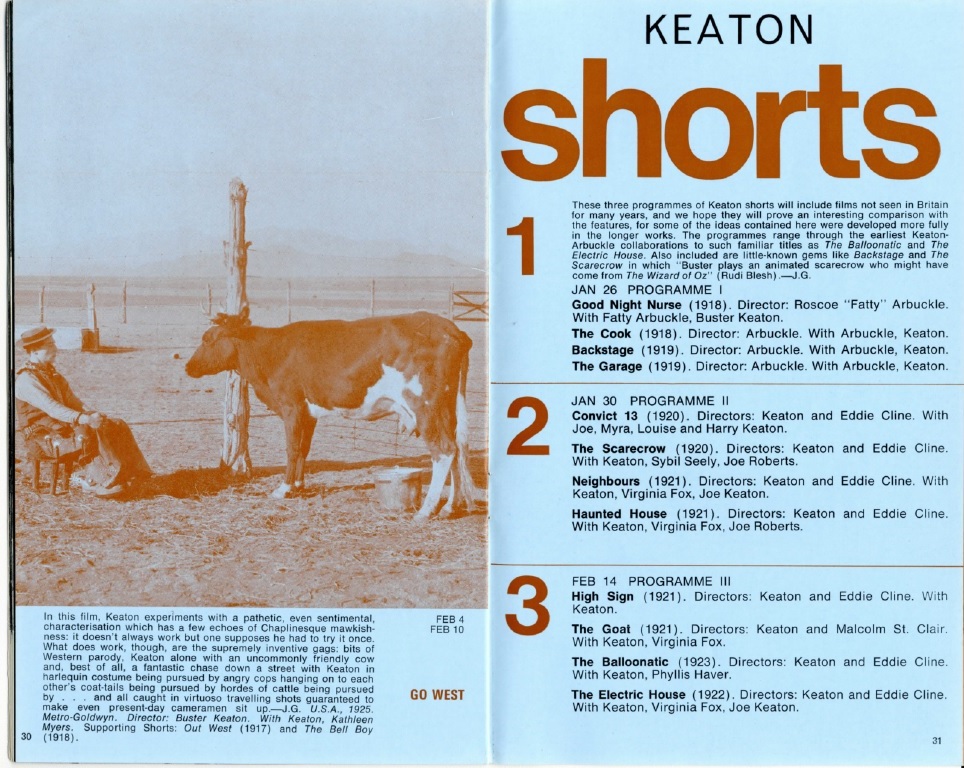

National Library Auditorium, National Film Theatre, Ottawa, 6–12 September 1968:

The Navigator,

Steamboat Bill, Jr.,

College,

Sherlock Jr.,

Our Hospitality,

Go West,

Seven Chances, and

The General.

|

|

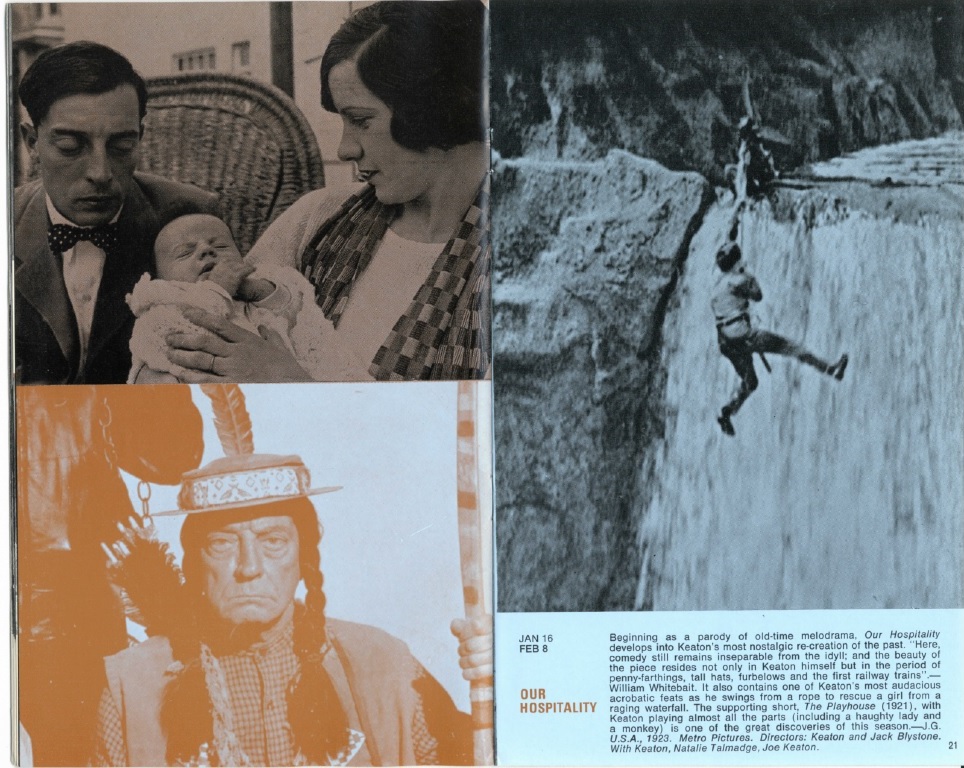

Ray intended to present a full Buster retrospective, 1917 through 1928,

at the Gallery of Modern Art in NYC in February 1968.

For reasons I have not learned, this never happened.

Instead, a month earlier, beginning on

16 January 1968,

Ray ran that retrospective at the National Film Theatre in London, England.

|

|

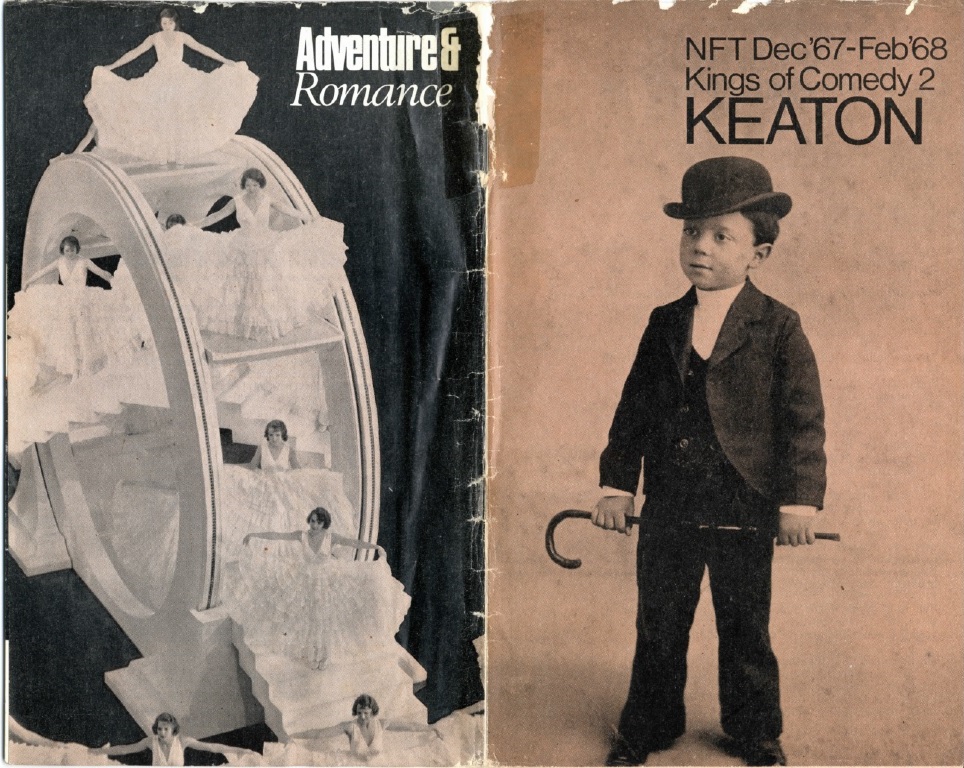

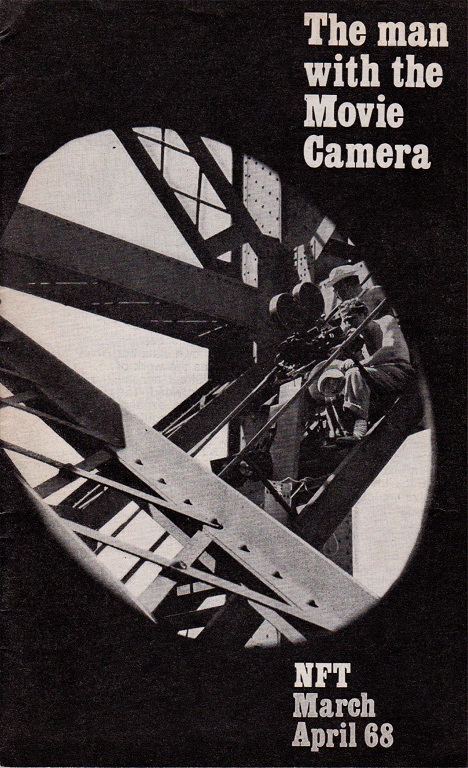

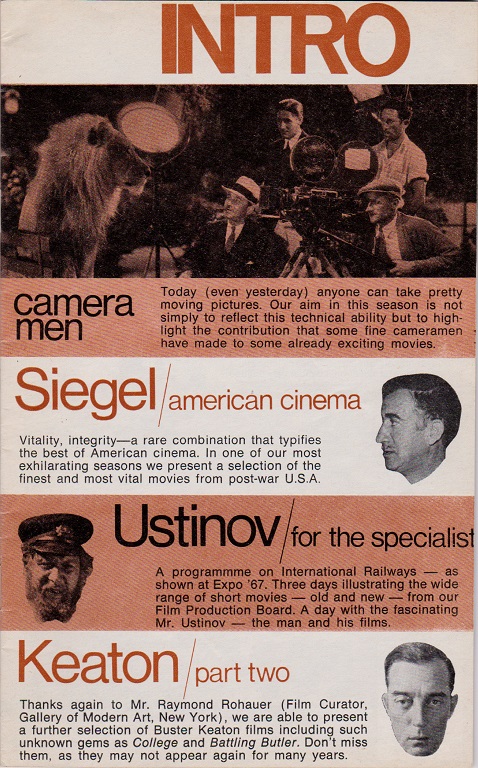

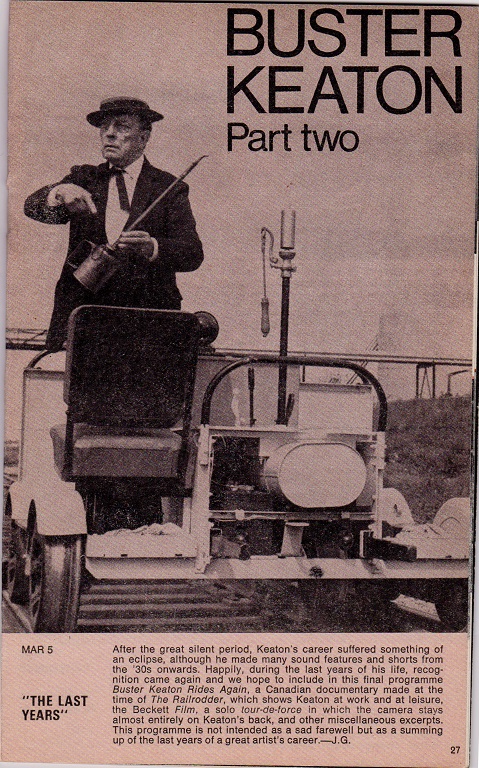

I just received

the BFI calendar for the above retrospective, and it is a revelation.

Here are the relevant pages:

|

|

|

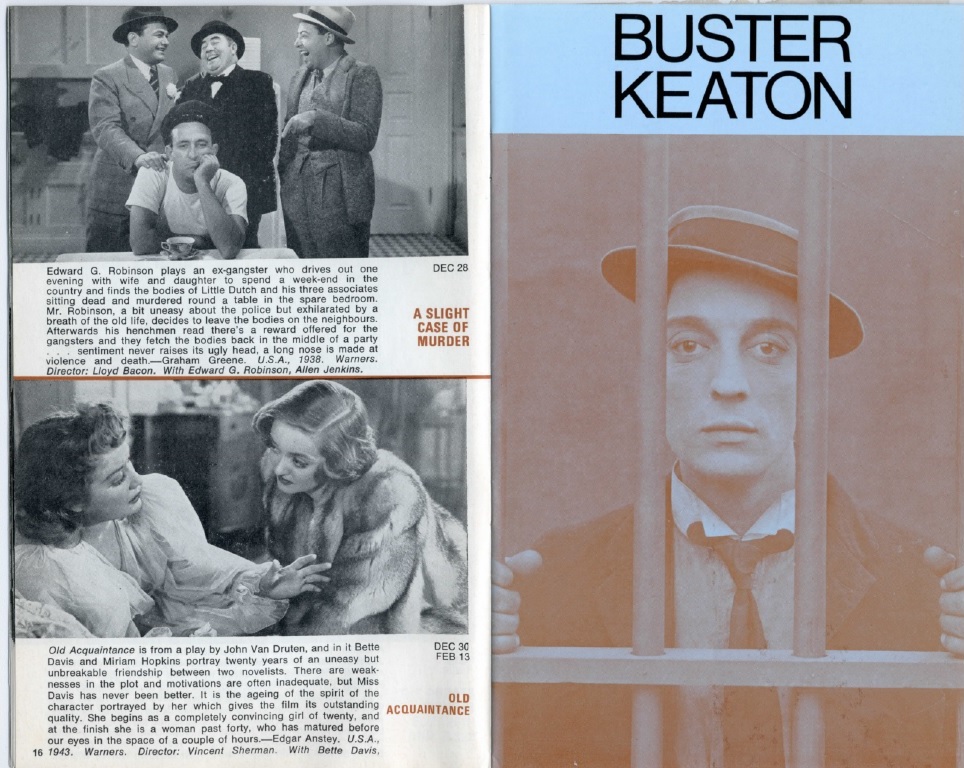

The Buster portions of that calendar were penned by John Gillett,

who had written the review of the 1963 Venice retrospective, which we saw above.

Let’s do an enhanced action replay of his opening:

|

|

BUSTER

At last the N.F.T.’s most

cherished plan has been realised —

a

|

|

Gillett’s words are most helpful, as they allow us to reconstruct the context of the time.

Buster was nearly unknown.

Paid members of film societies had seen several of his silents,

projected in 16mm in rented rooms, with 10 or 15 people in attendance,

likely with the clattering projector as the only aural accompaniment.

Laurel & Hardy were remembered pretty much only for their dreadful last few films.

Snub Pollard, Anita Garvin, Charley Chase, Max Linder, Alice Howell, Max Davidson, Bea Lilly, Harry Langdon were not even memories.

Harold Lloyd had withdrawn his films,

since he did not want them shown at the wrong speed accompanied by a tinkling piano.

He preferred that people not see his films at all rather than see them degraded in such a manner.

I can’t blame him.

So, when people thought of silent comics, or any older comics,

Charlie Chaplin was the only point of reference,

since some of his Keystone, Essanay, and Mutual shorts were still in circulation.

Charlie had no rights to them and so could not stop their exhibition.

Everybody considered Chaplin the best simply because he was the only one who was left, the only one who was known.

|

|

How different the situation had been forty years earlier!

Amidst the dross and dreck of studio-produced pabulum,

there were the bright shiny gems that were surprisngly plentiful.

Buster at the time was one of those jewels, but only one of them.

He was not the shining star.

He had company.

|

|

We in the 2020’s do not think of forty years ago as prehistoric,

because the pop culture of forty years ago still surrounds us

on video, on the Internet, on TV, on the radio.

How different the situation was in 1968!

Apart from the late-late-show fillers on television,

if it was more than six months old, it was rejected as past its due date.

Revivals were almost unheard of.

That is why Buster, who was effectively unknown to anyone under the age of 50,

was such a revelation.

|

|

So Chaplin, known for dupe copies of

|

|

In my personal opinion, I agree fully with John Gillett: Buster was the best of them all,

he had no peers, he outshone everyone else, his sense of cinema, his mastery of every machine,

his mastery of every cinematic technique, was unparalleled.

His storytelling sense was better than any of the others.

His sense of humor was easily the finest, but it still leaves me baffled.

He plays everything straight.

In all his features save his first, there is no clowning, no face pulling, no ridiculousness.

Everything is plausible and dead serious.

And yet we in the audience laugh uncontrollably.

I guess that is because the attitude expressed in those films resonates so well,

the attitude that the world is an automatic relay that inadvertently works against us,

that life is absurd, and that Murphy was an optimist, strikes a chord with us.

His perfectly plausible but entirely unexpected ways of solving problems

is such a surprise that we cannot help but scream with laughter.

But why do we laugh at his movies?

I still do not entirely understand.

L&H were clowns.

Charlie Chaplin was a clown, and an often unlikeable one, but yes, we laugh; we laugh at him more than with him.

Harold Lloyd was a straight comic, often unlikeable, but, again, we laugh at him more than with him.

The others do silly things in silly situations and make silly faces and wear silly costumes.

Buster took his sense of humor in an entirely different direction.

|

|

Now that so many silent comedies are so readily available

at special events at concert halls with full orchestras accompanying,

and also on

|

|

I doubt that there is anyone who personally likes Buster and Charlie equally.

There are lots of us who adore both, myself included, but for us,

our affections are directed more to one than to the other.

Charlie and Buster had very different personalities,

different attitudes towards life, and that comes through in their works.

They were polar opposites in most ways.

Charlie played upon our emotions.

Buster presented us with emotions but did not coerce us.

Charlie made agitprop. Buster made ironic observations.

|

|

So, when John Gillett argued that Buster was superior to Charlie,

what he meant, though he did not realize it,

was that Our Hospitality is superior to The Property Man.

Which it is.

|

|

Richard Warner kindly scanned the relevant pages from the following NFT calendar:

|

|

|

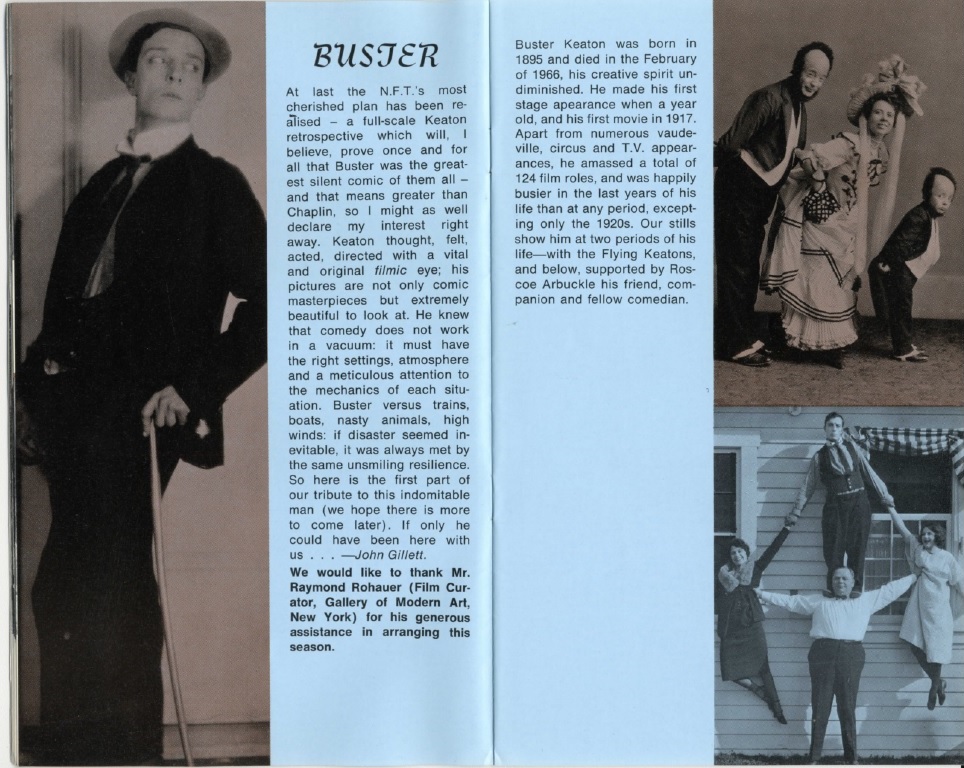

Zo, what we see in the above scanned pages is the third Buster retrospective.

The first was at the Cinémathèque Française in February/March 1962,

arranged by Henri Langlois and consisting, I presume, of prints that had been held at the institution for decades,

16fps without any musical accompaniment.

The second was the special program at the Venice Film Festival in September 1963, consisting of Rohauer’s prints,

presumably 24fps and presumably with live musical accompaniment.

This NFT series constituted the third retrospective, and it went over so well that Rohauer put the show on the road,

and that is what became the Buster Keaton Festival,

which toured parts of the world for the next 18 years or so,

until Rohauer finally passed away.

|

Claude Bolling |

|

In 1968, a French distributor by the name of

Jacques Robert licensed several of Buster’s movies from Rohauer.

The distributor wanted new scores on the soundtracks of

The Navigator,

Seven Chances, and

Steamboat Bill, Jr.

Since he was a fan of Claude Bolling, it was

Claude Bolling who wrote those scores!

I didn’t know that.

Did you know that?

All three of those movies were issued in 1969.

|

|

For The Navigator, Claude Bolling wrote the score for an ensemble of twenty musicians

and chose a style reminiscent of jazz music from the years 1930 to 1935, inspired by Duke Ellington.

The result was a success and encouraged the team to renew the experiment.

The next film, Seven Chances was adapted from a successful play by Roi Cooper Megrue.

Faced with impending bankruptcy, James Shannon learns that

he will inherit a significant sum of money from his grandfathers will if he is married on his 27th birthday.

The lively and virtuosic piano piece was later included in the program of some of Bolling’s Big Band’s concerts.

Steamboat Bill, Jr., was the last film directed independently by Buster Keaton.

It narrates an impossible love story between the children of two rivals, J.J. King and Steamboat Bill,

who want to take ownership of the navigation rights of each other’s steamboats on the Mississippi river.

Bolling also hired a Dixieland jazz band and a string orchestra to perform the lively score.

Recorded at Studio Davout, these three OSTs produced at the same period

have been selected and remastered from the composer’s original master tapes.

|

|

|

|

|

|

I like Claude Bolling, and this music is nice, really nice, but it doesn’t belong on these movies.

Claude Bolling had great talent, but he was never trained on scoring silent films.

In the 1910’s and 1920’s, the music supported the movies.

Nowadays, the movies are just quaint little add-ons underneath the overpowering music.

It’s

|

|

The CD, now sadly out of print, contains only two of the cues from Seven Chances,

but it includes 22 cues from The Navigator (45 minutes and 10 seconds)

and 26 cues from Steamboat Bill, Jr. (52 minutes and 22 seconds).

Those may well be all the cues, and, if so, there must have been repeats in the original soundtracks.

Lovely music, but it just doesn’t fit, I mean, not at all.

|

|

I assume that Jacques Robert issued more than just these three films in the late 1960’s and early 1970’s,

I assume that he distributed the first batch through

Film le Marais, about which I can learn nothing,

and I assume he distributed the second batch through Capital Films-Etoile Distribution of Paris,

about which I can learn nothing.

It seems that he included The General in the second batch.

What was on the soundtrack?

I don’t know.

Not Elfers. Not Erwin. Not Bolling.

It was something else, I’m sure, but what, I don’t know. Maybe Siracusa?

|

|

A reference card on The General published in March 2005 confirms

that the distributor was Capital. It says nothing more about that topic.

|

|

Apparently at least one of Bolling’s scores made its way to the Buster Keaton Festival,

namely Steamboat Bill, Jr., which ran from 26 August through 1 September 1981

at the Lincoln Plaza Cinema in NYC. (See Curtis, p. 689.)

|

|

Robert Hunt

on April 11, 2015 at 8:27 am

In the early 80s,

a friend of mine presented a series of

Keaton’s complete works at the St. Louis Art Museum.

Many of the films were not as easy to find as they are now,

so prints arrived from a variety of locations.

Several of the features

(I remember specifically “Seven Chances” and “The Navigator”)

had been restored in France with pastel title cards and original scores by Claude Bolling.

I’d love to see Kino find a way to add those scores to their Keaton collection.

|