|

|

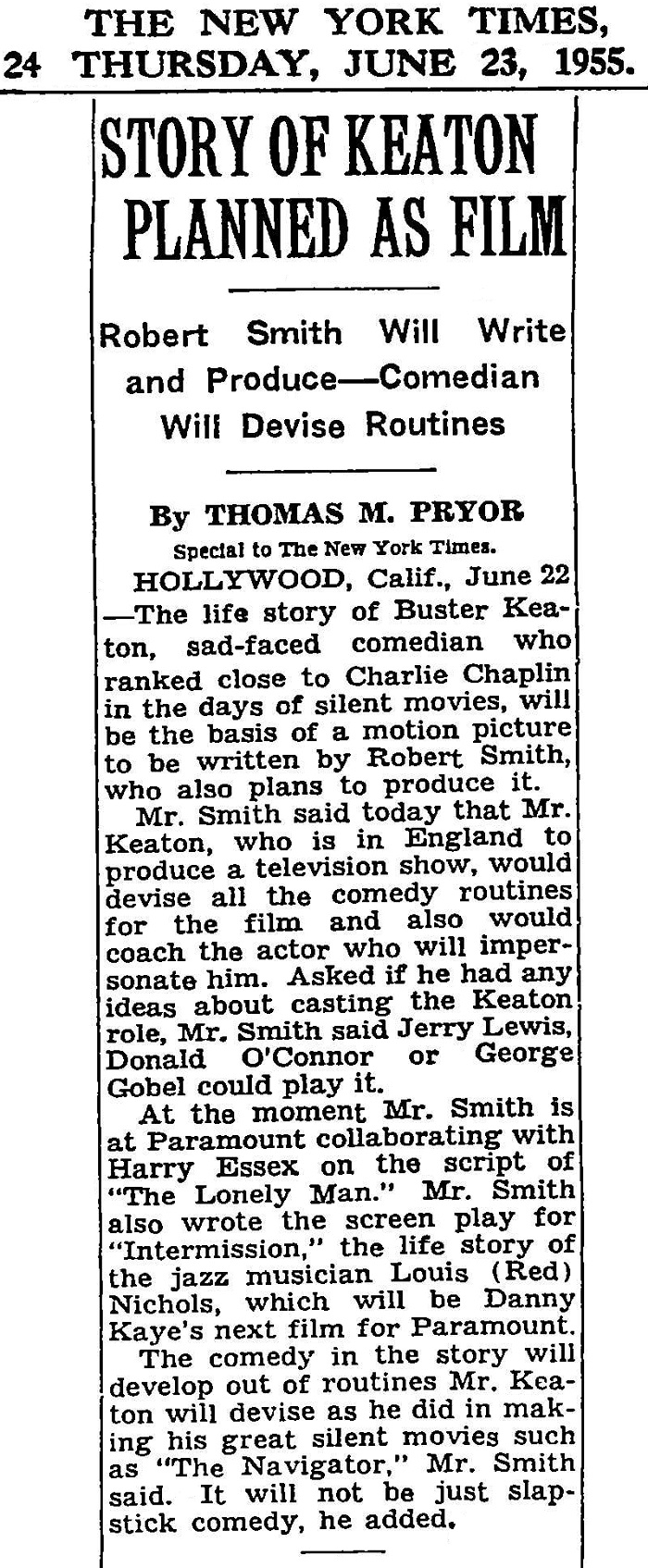

It was probably early in 1955 that aspiring screenwriter

Robert Smith

drafted a treatment for a screenplay about an abrasive circus clown

who somehow became a star in silent movies

but was headed towards a drunkard’s grave until a virtuous woman rescued him.

Well, I think that’s what the basic plot was.

I cannot be sure until I find that original treatment, if it still exists.

Robert Smith knew nothing whatsoever about cinema history

and so he just made everything up in the most cornball fashion imaginable.

It seems, from two subsequent treatments that I have read,

combined with what little I can recall of the movie,

that Smith at first wrote the story without a thought to any particular silent comic.

It was just a generic tale of a generic unfunnyman, a standard gimmick, nothing more.

|

|

Some or all of the drafts of the treatment and screenplay are on file at the Margaret Herrick Library.

The two I have so far read were early, but not the earliest.

By and by, I shall study and transcribe all the rest.

|

|

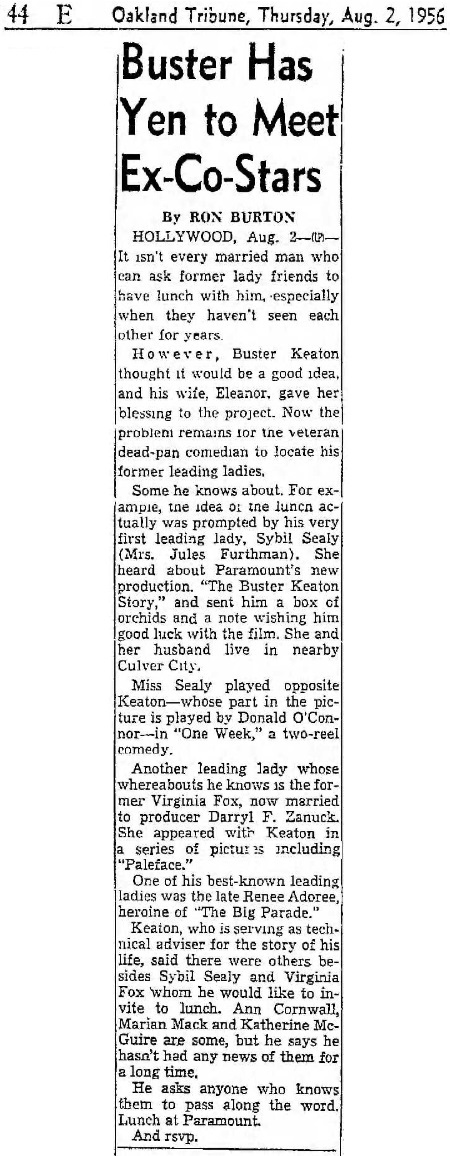

My guess (a guess, a guess, nothing more than a guess)

is that Robert Smith was unable to sell his treatment to any of the studios.

Then, in about

June 1955,

Smith somehow got the idea to attach a real name to his clown.

What made him pick the name Buster Keaton we may never know.

Could it be that he had heard through the grapevine

that something called the George Eastman Awards would be given out in November,

and that one of the recipients would be Buster Keaton?

Maybe. Maybe not.

|

|

Now that we bring it up, though, I think it high time to take a look at the Georges.

Open up your copy of Jim Card’s book, Seductive Cinema: The Art of Silent Film

(NY: Alfred A. Knopf, 1994), and turn to Chapter 15, page 280.

He tells the story.

|

|

In 1955, film festivals were proliferating throughout the entire

film-watching world. I had often wondered about how our PR-conscious

director, Oscar Solbert, felt about the Academy Awards

each year appropriating his given name for the golden statuettes that are

awarded. I should have anticipated that eventually he would counter

with some award of his own. Thus I was not entirely surprised when he

called me into his office one day and ordered me to set up a film festival

for Eastman House. “We will award Georges,” he announced. I firmly

believe he was confident that in a matter of time, the Oscars would be

superseded by Georges.

Usually I was reluctant to work very hard on any project that was

not of my own inception. But this one was proposed at just the right

time for me. I’d been brooding over the suicide of Clyde Bruckman.

The pioneer director and the one chosen by Buster Keaton to guide his

greatest films was reported to have killed himself in despondency over

being bypassed and forgotten. Yet his Keaton films were even then the

favorites of film societies and museums. More people, in fact, were looking

at the Keaton-Bruckman films at the time he killed himself than

there had been in the 1920s when Keaton comedies occupied a niche

only slightly higher than the Westerns. I had been wondering how best

to give belated recognition to the film artists who were still alive, whose

work was beginning to be really appreciated as creative accomplishments

to cherish as part of our cultural heritage, rather than simply

exploit as cute curiosities of a naive past. The general’s festivals might be

just the proper vehicles.

So I gave him the pitch that had been fermenting since Bruckman’s

passing. “General, the success of any film festival depends not on the

movies that are shown, but on the guest celebrities that are lured to

attend. Let’s meet this fact head-on. Our festival should not be just of

films, but a festival of film artists. Suppose we give awards to the greatest

living actresses, actors, directors and cameramen of specific periods of

the past. Let’s go back as far as we dare, as far as we can find great people

of the early days still alive. And let’s include cameramen. They’re always

being left out of the big events. We’re committed to photography — so

why don’t we honor the cinematographers on the same basis as the other

artists?”

The general bought it — and with his customary enthusiasm. “It’s a

great idea. Will you pick the people to be honored?”

“Of course not. We’ll let them choose themselves. Suppose we begin

with the 1915 to 1925 period. We’ll have Kodak’s people in LA get us the

addresses of every film actress, actor, director and cameraman who ever

worked during that decade. We’ll get Earl Blackwell and his celebrity

service to do the same for those in the East. Then we send them ballots

with every single survivor’s name on it. We let them pick the five top

players, directors and cameramen. Then the five winners in each category

we bring to Eastman House and give them the George Award.”

|

|

Buster was one of the winners, and he was immensely moved to have been chosen.

He held the George Award in higher esteem than any other.

As far as Buster had been concerned, showbiz was a living.

He put his heart and soul into anything he created, but still, it was just a living.

As far as I know, this was the first time he was recognized for artistry,

and it was not publicists or reporters who gave them that honor, but his own peers.

Together with the biography that Rudi Blesh had begun, on top of the interest that MoMA had expressed,

it was this George Award that probably began to change his attitude about his work and its value.

|

|

Robert Smith probably thought that studios might be more receptive

to a script based on a real celebrity than one based on a fictional celebrity.

He may have asked some acquaintances if they knew anything about this Buster Keaton fellow.

My guess is that someone said,

“Yeah, he was a kid in vaudeville, a star at four years of age, had an act with his parents called The Three Keatons.

He was a hit in silent pictures but became a drunk when sound came in.”

At that, Smith must have blurted out,

“That’s enough! Don’t tell me more. I’ve got it. Thanks!”

So he approached Buster Keaton with a proposal.

Could he name his clown Buster Keaton?

Buster agreed, for a thousand bucks.

Paid. Done deal.

Buster was convinced that nothing would ever come of this.

It was an easy grand, and that’s what he cared about.

|

|

Now, how could Robert Smith get a studio interested in his story?

Simple!

He could send out a press release implying that plans were already underway.

|

|

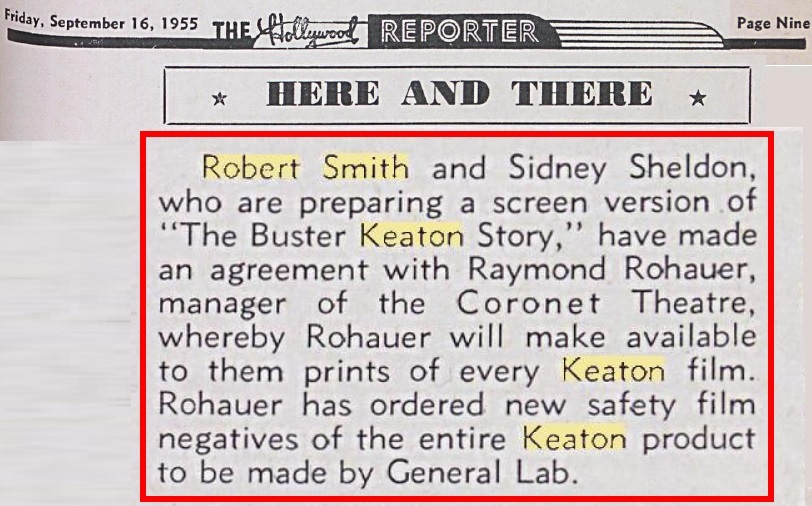

The above story is notable as much for what it does not say as for what it does.

It does not list Robert Smith’s previous production or direction credits, because he had none.

It establishes his credibility by mentioning two of his screenplays, neither of which had yet been filmed.

It states not that Smith will produce, but that he plans to produce.

It does not mention which studio is backing the production, because no studio was backing the production.

This news story was based on a press release that Smith mailed out from his home in the hopes of generating interest.

|

|

It would be a perfect vehicle, much easier to sell.

It would claim to be about a real celebrity

and it would include scenes of self-pitying and maudlin scenes of drunkenness

and tug-at-your-heartstrings sentimentalism topped off with reform

and a baby-makes-three-they-lived-happily-ever-after ending.

Just what the doctor ordered!

The studios would be falling over each other to purchase that story.

To adapt it for Buster required only that a few words be changed here and there.

|

|

Smith, already on staff at Paramount,

would not produce the film nor would he direct it.

He did not have the qualifications even to approach a studio about producing or directing.

He needed someone to stand behind.

He approached young director Sidney Sheldon

(yes, that Sidney Sheldon).

The two had never met before, and Sheldon had never heard of Smith.

He had, though, been a Buster fan since he was a kid, and he enthusiastically agreed.

By August(?) 1955, Robert Smith and Sidney Sheldon were officially production partners.

They would write the script together and Sidney would direct.

Sidney was sure the script could be fixed once Buster was at hand, but in that assumption he was woefully mistaken.

Robert and Sidney met with Paramount, which agreed to purchase sufficient shares to get the project off the ground,

and Sidney then announced The Buster Keaton Story at the end of

August 1955.

(This is neither here nor there, but my particular fascination is with Sidney Sheldon,

who serves as a tenuous link between my two favorite filmmakers,

Buster Keaton and Tinto Brass. Odd how the world works.

Coincidentally, Buster and Tinto were both 14:1 directors!)

|

|

It is probable that Smith had never seen even a single one of Buster’s movies.

That might explain his casting ideas.

He thought that George Gobel, a verbal comic, could portray Buster.

He also thought about Jerry Lewis.

If you think the movie as it stands is awful, imagine how much worse it would have been with Jerry Lewis.

That would have been prosecutable as a crime against humanity.

He also thought about

Donald O’Connor, a professional dancer.

Buster was okay with either George or Donald, but with a preference for Donald, who could do physical comedy.

Donald got the job, and, bless him, he threw a fit to change the script to replace the circus with vaudeville.

|

|

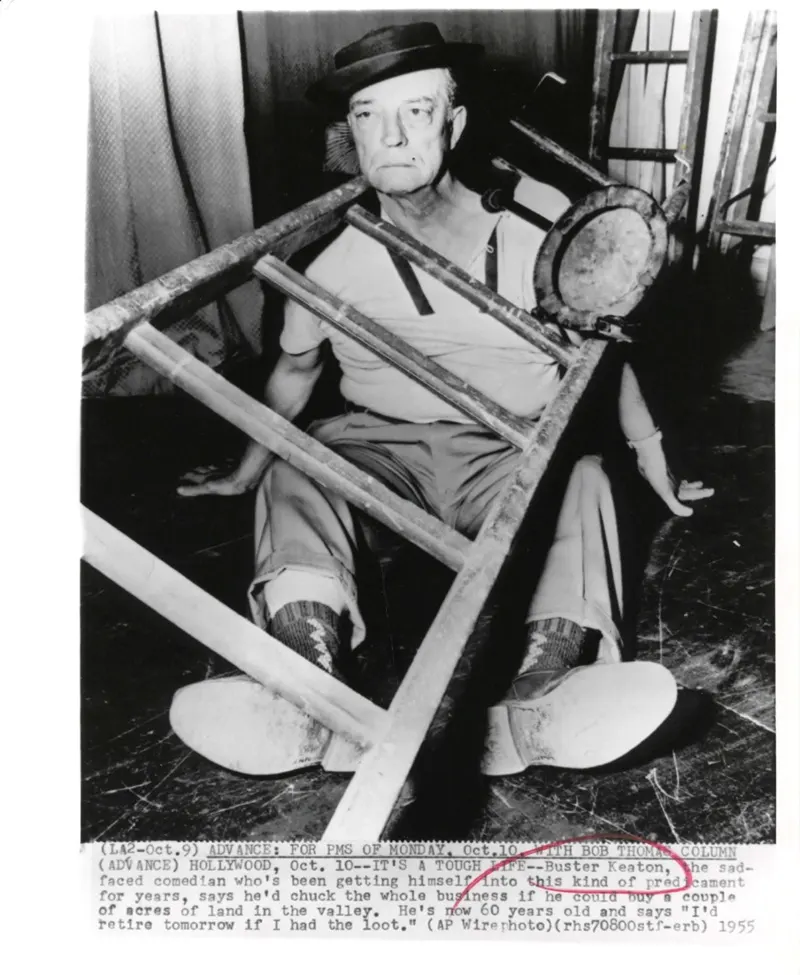

Robert Smith looks with proud satisfaction at the file copy of his script. Donald O’Connor silently looks over at Buster as if to say, “Well, what can I say?” Buster silently looks at Donald as if to say, “You’ve gotta be kiddin’ me.” |

|

Robert and Sidney now needed to watch some Buster movies in order to prepare their movie,

and they surely asked around for prints.

The only available films were MoMA’s 16mm circulating prints of

Sherlock Jr.,

The Navigator, and

The General.

Those prints were perpetually being shipped to various high schools and public libraries and clubs and so forth,

and chances of booking them on short order were slim, but they managed to rent at least The Navigator.

At one time or another they also managed to rent Sherlock Jr..

Eventually they saw The General as well.

Did they see MoMA’s print or AMPAS’s print?

I doubt they saw either.

They probably saw MGM’s print.

Yes, MGM had briefly considered remaking The General with Red Skelton in the lead,

and so the bigwigs ordered a fine grain and a print.

Upon screening the movie, they probably nixed it as too expensive.

Instead, they made A Southern Yankee.

In the meantime, the fine grain and the print remained in the vault.

|

|

During discussions with Buster, Robert and Sidney surely asked if there were any other films they could see.

As a matter of fact, there were.

Just ask Ray Rohauer.

|

|

Curtis, on page 582, relates that the Sheldon trio viewed Steamboat Bill, Jr.,

in addition to The General.

Kevin Brownlow confirms that when Donald O’Connor saw The General

he was so stunned that he called Buster “the D.W. Griffith of comedy.”

(See Brownlow, Alla ricerca di Buster Keaton, p. 109.)

Both those films were by now with the Academy.

Perhaps they viewed a safety dupe of Steamboat Bill, Jr.,

in an Academy screening room or on one of the Academy’s flatbeds?

Maybe. Maybe not. I tend to think not.

I tend to think they watched a 16mm print that Ray Rohauer had recently ordered from General Film Laboratories.

Curtis suggests further that the budget did not allow for any recreations of the scenes contained in those two movies.

If memory serves, The General is not even hinted at in The Buster Keaton Story,

and that’s a pretty profound omission.

|

|

|

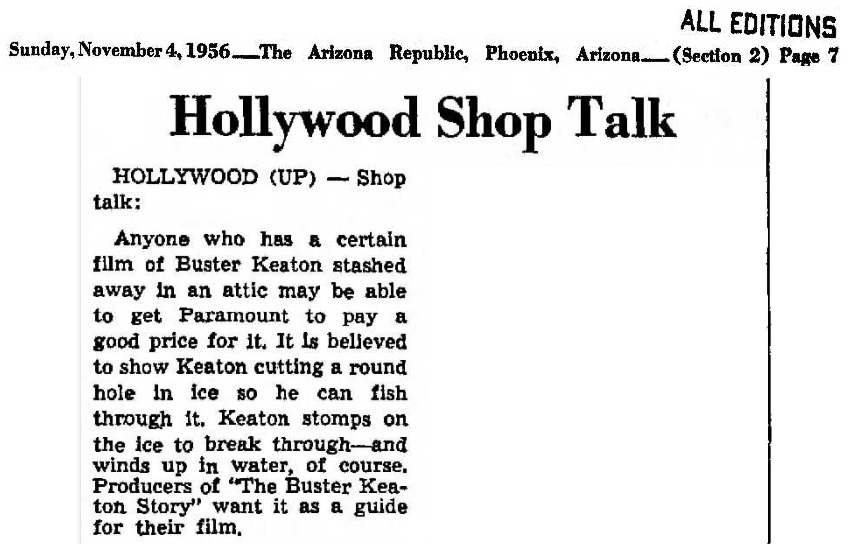

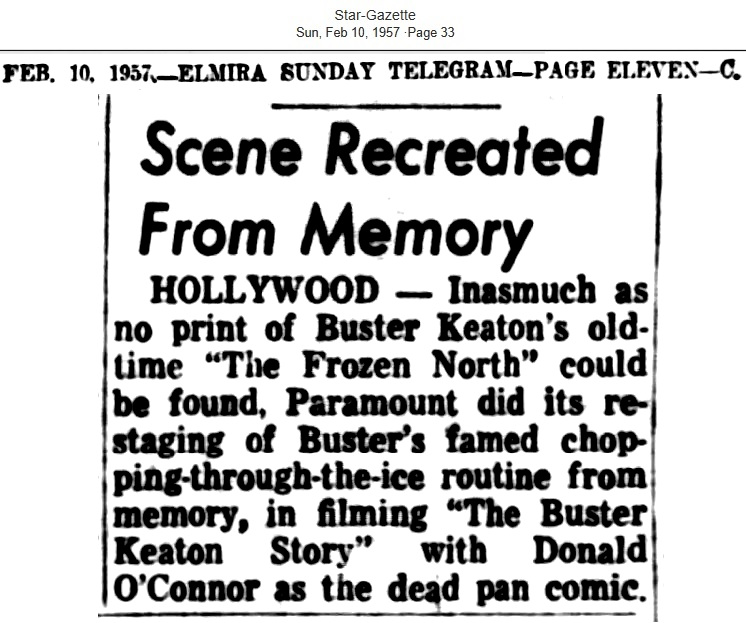

As usual, hastily written news items are riddled with errors.

Ray was not the manager of the Coronet.

His Society of Cinema Arts leased the Coronet on the days when no sets were on stage.

He did not and could not provide prints of every Keaton film,

because nobody in the world had (or has even now) prints of every Keaton film.

He provided what he could, and that constituted “[nearly] every [extant] Keaton [silent] film.”

What he provided were almost certainly all 16mm prints.

In later interviews, Ray claimed that after Three Ages gummed up the printer in the summer of 1954,

General Film Laboratories refused to accept his orders anymore.

Yet here he is in September 1955 still taking his jobs to General Film Laboratories!

So much for that story!

|

|

That was not my only discovery.

Brace yourselves.

|

|

|

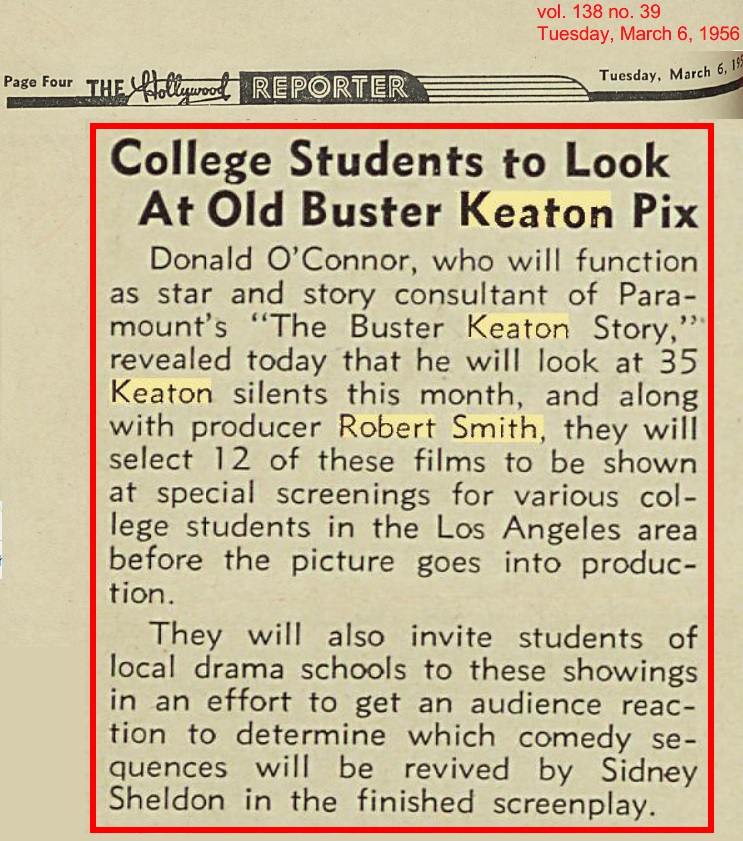

Yes, Donald O’Connor, Robert Smith, and Sidney Sheldon showed some of Buster’s movies to college kids,

and Buster attended at least one screening, namely of The General, as we shall learn.

Oh how I would love to get a schedule of all those screenings!

The arithmetic, as you can see, is a mess.

Robert, Sidney, and Donald were able to view only 28 of Buster’s silents, not 35.

Robert and Sidney made this clear in a note to the Paramount executives.

Of those 28, no more than 25 could have been from Ray Rohauer.

Sherlock Jr. and

The Navigator definitely came from MoMA, and

The General could have come from MoMA or maybe AMPAS but I think most likely MGM,

which had a print and a fine grain in its vaults.

I bet it was Buster who told the gang about that print.

That makes me curious: What were the 25 that Ray supplied?

|

|

Below is a list of all of Buster’s starring silents.

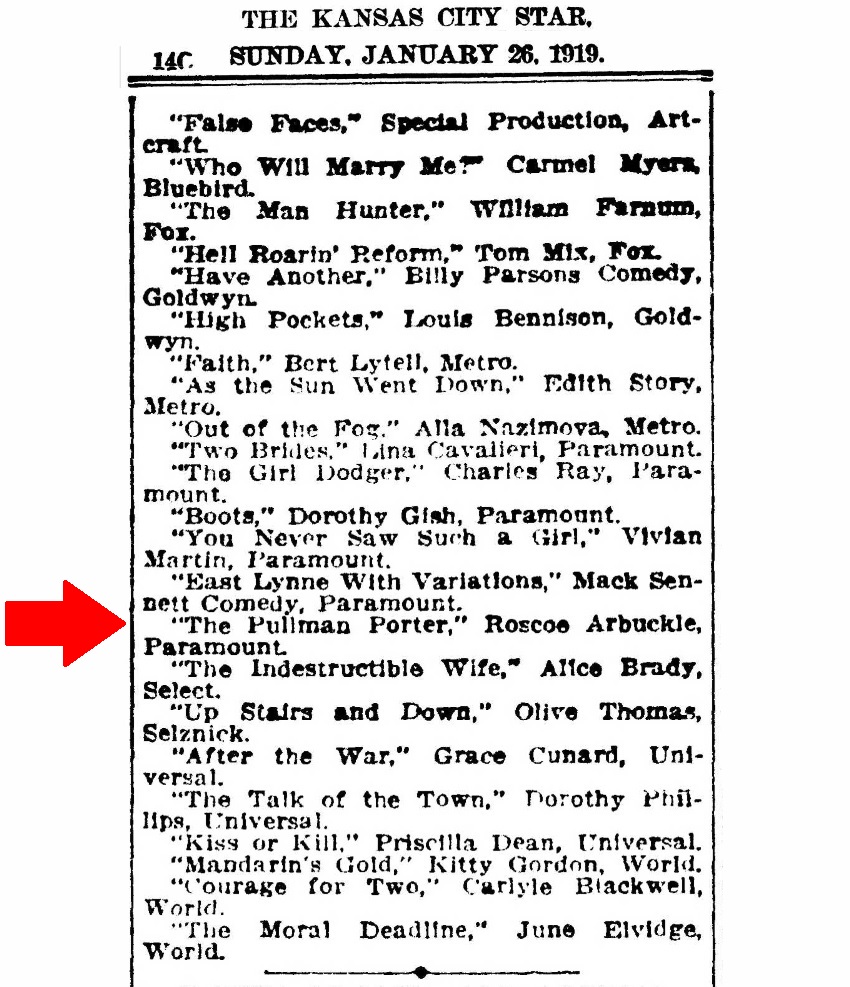

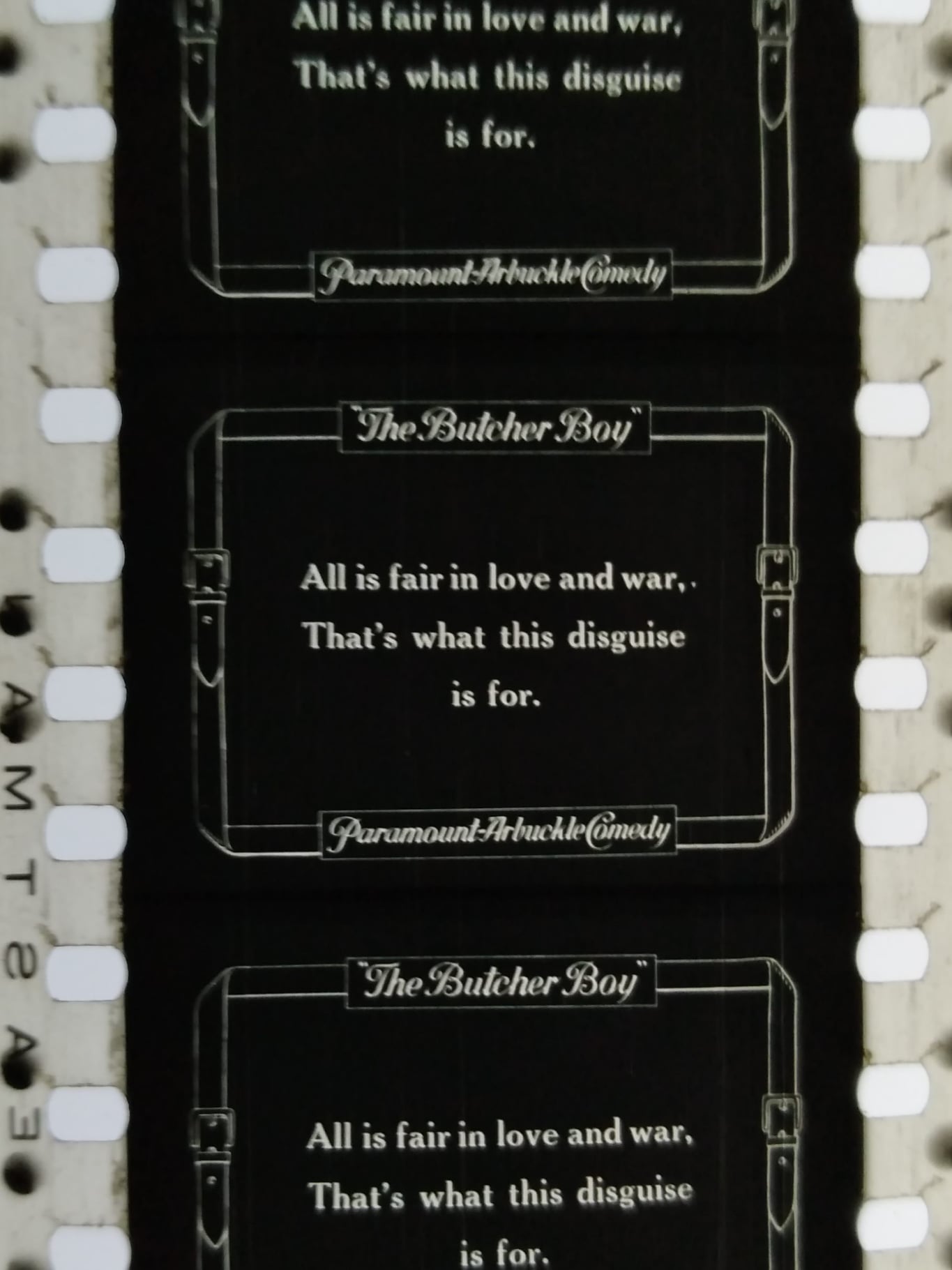

Of the first 14, The Butcher Boy through The Garage, at most only two were available in the 1950’s.

Rudi Blesh wrote his book on Keaton from October 1953 through probably March 1956, though he did not get it published until 1966.

It is clear from his text that he had never seen a single one of the Roscoe/Buster movies.

It appears to me that when the Cinémathèque française presented the world’s first Busterfest in February/March 1962,

none of the Roscoe/Buster movies was included.

Marcel Oms wrote his pamphlet in 1963 (published January 1964) and he was able to locate only three Roscoe/Buster movies:

The Butcher Boy (Fatty garçon boucher),

The Hayseed (Un garçon séduisant), and

The Garage (Malec et Fatty garagistes d’occasion), none of which he found funny or enjoyable in any way at all.

He was able to see them courtesy of

Raymond Borde

of the Toulouse

|

|

When we put the above information together,

we see that the BFI somehow acquired Coney Island by 1960,

and that Raymond Borde revealed in 1963 that he had The Butcher Boy, The Hayseed, and The Garage.

In or shortly before 1967, Ray Rohauer managed to acquire

The Rough House (which he misidentified as The Cook),

Goodnight Nurse, and

Back Stage.

|

|

By the time David Robinson published his booklet on Buster Keaton

(London: Secker & Warburg / BFI,

January 1969,

15s; Bloomington: Indiana University Press,

May 1969, $5.95 cloth, $1.95 paper),

one more Roscoe/Buster movie had turned up in Moscow, definitely in 1968.

Thus was Robinson able to view Out West, which Ray Rohauer misidentified as A Desert Hero.

|

|

I have tried and failed to view The Buster Keaton Story again.

It is on YouTube and Archive.org and other places for free, but I can’t bring myself to look at it.

I did scroll through it to identify which routines were restaged for the cameras.

I counted maybe only seven.

I was wrong.

There were more.

Fortunately, someone who calls himself (herself?)

The Biopic Story

was born with the gift of a

|

|

The Biopic Story, The Buster Keaton Story - scene comparisons, posted on Nov 12, 2020. When YouTube disappears this video, download it. |

|

In the list below, I put strikes by the films that the trio definitely did not see.

I inserted check boxes by the films they definitely studied,

whether or not they included

|

|

To add to this data, we can discern from Rudi’s book that he saw

The Play House,

The Boat,

The Paleface,

Cops,

The Balloonatic (a British sound print retitled Balloonatics),

as well as

Three Ages,

Our Hospitality,

Sherlock Jr.,

The Navigator,

Go West,

Battling Butler,

The General,

College, and

Steamboat Bill, Jr.

As for The Cameraman, Rudi relied on his memories from 1928.

Richard Warner explained that I was wrong to have concluded that Rudi saw

The Electric House or Day Dreams as he was writing his book in the 1950’s.

He had seen The Electric House back in 1922 or 1923 and misremembered it wildly,

confusing part of it with The Goat.

As for Day Dreams, Rudi had not seen it at all

until 1963 when he caught some clips in Youngson’s compilation film,

30 Years of Fun.

Ahhhhhh. Now it all made sense.

And with that, ready? Here goes:

|

| Viewed by trio? |

TITLE | Where was it found? | Comment | Viewed by Rudi? |

Re-enacted in TBKS? | © | |

| — | The Butcher Boy Prod: |

Toulouse in early 1963 | No | No | PD | ||

| — | The Rough House Prod: A7003, Rel. ca. 06 Jun 1917 ( |

Prague bet. 1964 and 1967 | Misidentified as The Cook | No | No | PD | |

| — | His Wedding Night Prod: A7004, Rel. ca. 20 Aug 1917 |

Amsterdam bet. 1976 and 1995 | No | No | PD | ||

| — | Oh! Doctor Prod: A7005, Rel. ca. 30 Sep 1917 |

Italy, 1995, by Lobster Films | No | No | PD | ||

| Coney Island Prod: A7006, Rel. ca. 29 Oct 1917 |

????? | Was this available in the 1950’s? | No | No | PD | ||

| — | A Country Hero Prod: A7007, Rel. ca. 10 Dec 1917 |

Lost film | No | No | PD | ||

| — | Out West Prod: A7008, Rel. ca. 20 Jan 1918 |

Moscow, 1968 | Misidentified as A Desert Hero | No | No | PD | |

| — | The Bell Boy Prod: A7009, Rel. ca. 18 Mar 1918 |

Paris bet. 1969 & 1974 | No | No | PD | ||

| — | Moonshine Prod: A7010, Rel. ca. 13 May 1918 |

16mm bootleg (or 8mm?) discovered in Paris bet. 1969 & 1976 | MoMA has a few 35mm fragments | No | No | PD | |

| — | Good Night Nurse Prod: A7011, Rel. ca. 08 Jul 1918 |

Denmark circa 1967 | No | No | PD | ||

| — | The Cook Prod: A7012, Rel. ca. 15 Sep 1918 |

Norway, 1999 | No | No | PD | ||

| |||||||

| — | Back Stage Prod: A7018, Rel. ca. 07 Sep 1919 |

Amsterdam bet. 1964 & 1967 | No | No | PD | ||

| — | The Hayseed Prod: ????, Rel. ca. 26 Oct 1919 |

Toulouse circa 1963 | No | No | PD | ||

| — | The Garage Prod: ????, Rel. ca. 20 Jan 1920 |

Toulouse circa 1963 | No | No | PD | ||

| The “High Sign” Prod: K-1, Prev. Apr 1920 Rel. ca. 12 Apr 1921 |

Camera negative in MGM vault; workprint or preview print found elsewhere (Buster’s garage?) |

No | No | Loew’s R 40934 10 Dec 48 | |||

| The Saphead Prod: ????, Rel. 18 Oct 1920 |

Onsite at AMPAS | Shown in London in 1968; reissued in 1974 | No | No | Loew’s R 38228 27 Sep 48 | ||

| One Week Prod: K-2, Rel. 01 Sep 1920 |

Camera negative in MGM vault | No | No | PD | |||

| — | Convict 13 Prod: K-3, Rel. 27 Oct 1920 |

R2 Prague circa 1962; 16mm R1 Buenos Aires circa 1980 |

There’s a better 35mm print in Moscow. | No | No | PD | |

| The Scarecrow Prod: K-4, Rel. 17 Nov 1920 |

Camera negative in MGM vault | No | No | Loew’s R 39727 26 Oct 48 | |||

| Neighbors Prod: K-5, Rel. ca. 22 Dec 1920 Working title: The Back Yard |

Camera negative in MGM vault | No | No | Loew’s R 40456 17 Nov 48 | |||

| The Haunted House Prod: K-6, Rel. ca. 10 Feb 1921 |

Camera negative in MGM vault | No | No | Loew’s R 40934 10 Dec 48 | |||

| — | Hard Luck Prod: K-7, Rel. ca. Feb 1921 |

Partially reconstructed in 1987 from 3 fragments | Much is still missing. Lobster Films recently filled in a gap with animation. | No | No | PD | |

| 🗹 | The Goat Prod: K-8, Rel. ca. 18 May 1921 |

Available in 16mm; camera negative in MGM vault | In 1921 | Yes | Loew’s R 47217 29 Apr 49 | ||

| 🗹 | The Play House Prod: K-N-1, Rel. ca. 06 Oct 1921 Advertising materials supply the title as The Playhouse |

Buster’s garage and Mason’s bunker | Video releases have replacement titles | Yes | No | PD | |

| 🗹 | The Blacksmith Prod: K-N-2, Rel. ca. 21 Jul 1922 (release delayed pending revisions) Working title: The Village Blacksmith, 1,746' |

Mason’s bunker (preview version) | No | No | PD | ||

| 🗹 | The Boat Prod: K-N-3, Rel. ca. Nov 1921 |

Buster’s garage and Mason’s bunker | Yes | Yes | PD | ||

| 🗹 | The Paleface Prod: K-N-4, Rel. ca. Jan 1922 |

Mason’s bunker | Yes | Yes | PD | ||

| 🗹 | Cops Prod: K-N-5, Rel. ca. Mar 1922 |

Mason’s bunker | Yes | Yes | PD | ||

| 🗹 | My Wife’s Relations Prod: KN-6, Rel. ca. May 1922 |

Mason’s bunker | No | No | PD | ||

| — | The Frozen North Prod: KN-7, Rel. ca. Aug 1922 Working title: Snow Stuff |

Prague in 1962 or 1963 | No | Yes, blindly | PD | ||

| — | The Electric House Prod: KN-8, Rel. ca. Oct 1922 2,231' |

Prague circa 1967? | In 1922/23 | No | PD | ||

| — | Day Dreams Prod: KN-9, Rel. 27 Nov 1922 Working title: The Vision 2,493' |

Fragments found in Prague circa 1955? | No | No | PD | ||

| — | The Love Nest Prod: KN-10, Rel. ca. Mar 1923 (release delayed) |

Paris and Amsterdam circa 1980 | No | No | PD | ||

| 🗹 | The Balloonatic Prod: KN11, Rel. ca. 22 Jan 1923 2,152' |

Mason’s bunker; reissued in 1935 in Germany, France, & UK in 35mm & 16mm with music | Yes | Yes | PD | ||

|

Three Ages Prod: KN-20, Rel. 25 Jun 1923 (London) 14 Jul 1923 (San Francisco) 5,251' Ernst Luz cue sheet |

Buster’s garage | Yes | No | PD | |||

|

Our Hospitality Prod: K21, Rel. 03 Nov 1923, 6,220' Working title: Hospitality |

Portions in Mason’s bunker; onsite at MoMA | Yes | No | Loew’s R 86345 19 Nov 51 | |||

| 🗹 |

Sherlock Jr. Prod: K22, Prev. 19 Feb 1924 & 2 other dates Rel. 14 Apr 1924 4,065' |

Buster’s garage; portions in Mason’s bunker; MoMA | Yes | Yes | Loew’s R 92525 25 Mar 52 | ||

| 🗹 |

The Navigator Prod: K23, Rel. ca. 13 Oct 1924 |

Buster’s garage; portions in Mason’s bunker; MoMA | Yes | Yes | Loew’s R 98731 18 Aug 52 | ||

| — |

Seven Chances Prod: K24, Rel. ca. 16 Mar 1925 |

Discovered circa 1965 | Repremièred Sep 1965 at NY Film Fest | No | No | Loew’s R 106805 04 Feb 53 | |

|

Go West Prod: K25, Rel. ca. 25 Oct 1925 |

Buster’s garage; onsite at MoMA and GEH | Yes | No | Loew’s R 117711 22 Sep 53 | |||

| 🗹 |

Battling Butler Prod: K26, Rel. ca. 22 Aug 1926 |

Mason’s bunker; onsite at MGM | Yes | No | Loew’s R 133178 08 Jun 54 | ||

| 🗹 |

The General Prod: K27, Rel. 11 Dec 1926 7,084' James C. Bradford cue sheet |

Mason’s bunker; MoMA; onsite at MGM | Yes | No | PD | ||

| 🗹 | College Prod: K28, Rel. ca. 10 Sep 1927 Ernst Luz cue sheet |

Buster’s garage and Mason’s bunker | Yes | Yes | PD | ||

| 🗹 | Steamboat Bill, Jr. Prod: ????, Rel. 05 Apr 1928 |

Buster’s garage and Mason’s bunker | Yes | Yes | PD | ||

| — |

The Cameraman Prod: 366, Rel. 22 Sep 1928 6,930' |

Not available at the time | In 1928 | No | Loew’s R 172845 22 Jun 56 | ||

| 🗹 |

Spite Marriage Prod: 407, Rel. ca. 06 Apr 1929 Ernst Luz cue sheet |

Onsite at MGM | No | Yes | Loew’s R 187693 06 Mar 57 | ||

|

Now, think a moment.

According to Jim Curtis (page 611), Ray did not begin acquiring his Buster collection until late in 1959.

Yet, according to Jim Curtis (page 607), Ray “served as a source for Robert

Smith, who asked him to help locate some of the shorts and features that

he, Sidney Sheldon, and Donald O’Connor wanted to study for The Buster

Keaton Story” — in early 1956!!!!!

Is there a way to harmonize those two statements?

Theoretically, yes!

If Ray knew where he could borrow, say, five or six films in 16mm, he could have shown those to the Smith-Sheldon-O’Connor trio,

and then a few years later he could have begun his 35mm collection in earnest.

Yet that does not fit the rest of the information.

Olga sent me a snippet from an unpublished interview that Marion Meade conducted with Sidney Sheldon:

|

|

Marion Meade: Okay, I just want to ask you one other thing. Do you recall a man who was kind of associated with him by the name of Raymond Rohauer?

Sidney Sheldon: I do. I got us some film with him.

Marion Meade: But he wasn’t involved in the...

Sidney Sheldon: Not at all.

Marion Meade: Okay, he just supplied the film that was used, or just for your...

Sidney Sheldon: ...film not that was used, because we shot all the things fresh. But old films on Buster he was able to get hold of.

|

|

Not too specific, is it?

We need more information.

All right.

At the Margaret Herrick Library in Beverly Hills is a file box on The Buster Keaton Story.

One of the manilla folders inside is labeled “Paramount Pictures scripts

|

|

We have made two surprising and delightful discoveries

about Keaton comedy. (1) It doesn't date. Play "The General,"

"The Navigator," "Battling Butler," before an audience now.

Despite the jerky movements of the film, the lack of sound and

sound effects, the people in the theatre laugh as loudly as they

ever did. Sometimes they applaud spontaneously. (2) Any experienced

comic can play the routines as well as Buster. Even

Oscar Levant was hilarious when the orchestra of a Metro musical

turned around and the violinist, the horn player, the drummer,

And the oboe man, all were Oscar. The whole sequence was lifted

intact from an early Keaton two-reeler, "The Showhouse."

Put a Buster Keaton routine in the hands of a really fine

comic, a George Gobel, a Hope, a Kaye, a Donald O'Connor, a

Jerry Lewis, a Red Skelton and he will rise to new heights. Surely

Skelton reached his all-time peak in the sequence of "Neptune's

Daughter" where, as a fake Argentine polo player, he was hoisted

on the back of a Percheron by block and tackle. This routine was

probably the longest and loudest single yock in the history of

talking pictures (run it before an audience and see). And every

move and gesture of it was created and taught to Red by Buster,

who was on

We have viewed 28 Buster Keaton silent pictures, and were

pleased to discover that while many of Buster's routines have been

imitated by modern comedians, there are still a hundred or more of

the funniest and best that have never been touched.

Many of these will fit exactly, and hilariously, into a

biography of Keaton. That biography, of course, will be freely

adapted to make the finest possible motion picture. As the Jolson

Story wasn't exactly the life of Al, and "Caruso" might never have

been recognized by Enrico's life, so we're taking a few liberties

with "Buster." But what "Caruso" and "The Jolson Story" did with

the life of a great operatic singer and a great entertainer, in

terms of both financial and artistic success, we expect to approximate

with the life of a great comedian.

Here then is the Buster Keaton Story, most of it true in

fact, and all of it true in spirit. A story of laughter laced with

tears, a story of the human heart, now sad, now gay.

|

|

Zo, how on earth could they have viewed 28 of Buster’s silent films

if only three features were available from MoMA

and if Ray Rohauer had been able to borrow or purchase a few others?

|

|

The routines that Smith, Sheldon, and O’Connor

|

|

Apart from The Goat, which was circulating in 16mm to film clubs,

the trio did not

|

|

The Smith-Sheldon-O’Connor trio did not watch The Cameraman.

As you can hear from

the 1958 interview conducted by George Pratt,

Buster was surprised to learn that The Cameraman still existed

(though minus the first three+ minutes of Reel 3).

Might the trio have managed to see Coney Island?

Even if they did, we still have not reached a total of 28.

Seven Chances was not rediscovered until

sometime in 1965, which led to its 16mm repremière at the NY Film Festival that September.

|

|

Where and how Seven Chances turned up, I wish I knew, but as Ray Rohauer explained to Kevin Brownlow

in Alla ricerca di Buster Keaton, page 238:

|

|

A lot of times you can’t discuss how the films were found because there

are a lot of people involved in the background and you could step on toes

which would prevent you from getting other things. There are certain

confidences in finding material on films that were supposedly destroyed.

There’s a certain secretiveness in archive work and you mustn’t betray a

confidence, no matter what.

|

|

Ahhhhhhhh. I see. One of Ray’s confidants at a silver-reclamation lab

or maybe at a film exchange snuck it to him

late at night when no one was looking.

Or maybe an ally at MGM noticed it on a shelf in the vault and realized it had been left there by mistake.

He then phoned Ray with a Hello that contained a secret code word,

and at two o’clock in the morning a van stopped for a moment in back of a bakery and a quick exchange was made.

|

|

What Ray explained was all too true.

|

|

By the process of deduction, the following are the 15 movies that the Smith-Sheldon-O’Connor trio definitely studied:

|

|

01. The Goat

02. The Play House 03. The Blacksmith 04. The Boat 05. The Paleface 06. Cops 07. My Wife’s Relations 08. The Balloonatic 09. Sherlock Jr. 10. The Navigator 11. Battling Butler 12. The General 13. College 14. Steamboat Bill, Jr. 15. Spite Marriage |

|

So we are 13 films short.

Which 13 other films did the Smith-Sheldon-O’Connor trio study?

At most, only another 10 were available, not 13.

Not sure, but Coney Island may have been written off as a lost film at the time.

For the sake of argument, let’s add it in anyway.

That way we get another 10:

|

|

01. Coney Island

02. The “High Sign” 03. The Saphead 04. One Week 05. The Scarecrow 06. Neighbors 07. The Haunted House 08. Three Ages 09. Our Hospitality 10. Go West |

|

So we are still 3 films short.

What on earth could those other 3 films have been?

Maybe Screen Snapshots of 5 January 1922?

Maybe Screen Snapshots of 27 April 1922?

Maybe Screen Snapshots of 2 July 1922?

Maybe Screen Snapshots of 30 July 1922?

Maybe Screen Snapshots of 17 December 1922?

Maybe Screen Snapshots of 28 January 1923?

Maybe Screen Snapshots of 16 December 1923?

Maybe Screen Snapshots of 15 September 1924?

Maybe Screen Snapshots of 1 November 1924?

Maybe Screen Snapshots of 1 May 1926?

Methinks that Robert and Sidney miscounted.

They saw 24 of Buster’s silents, or maybe 25, but definitely not 28.

|

|

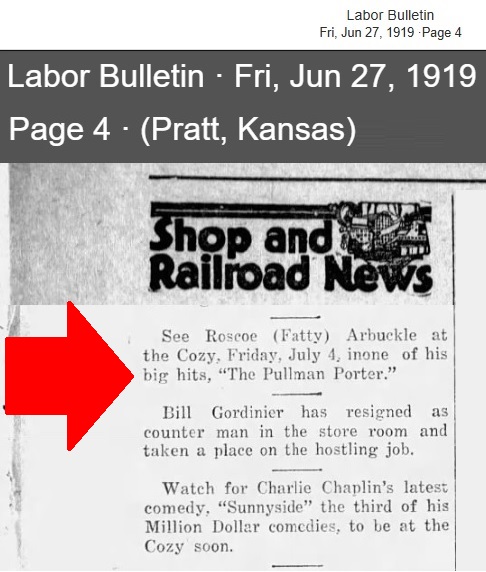

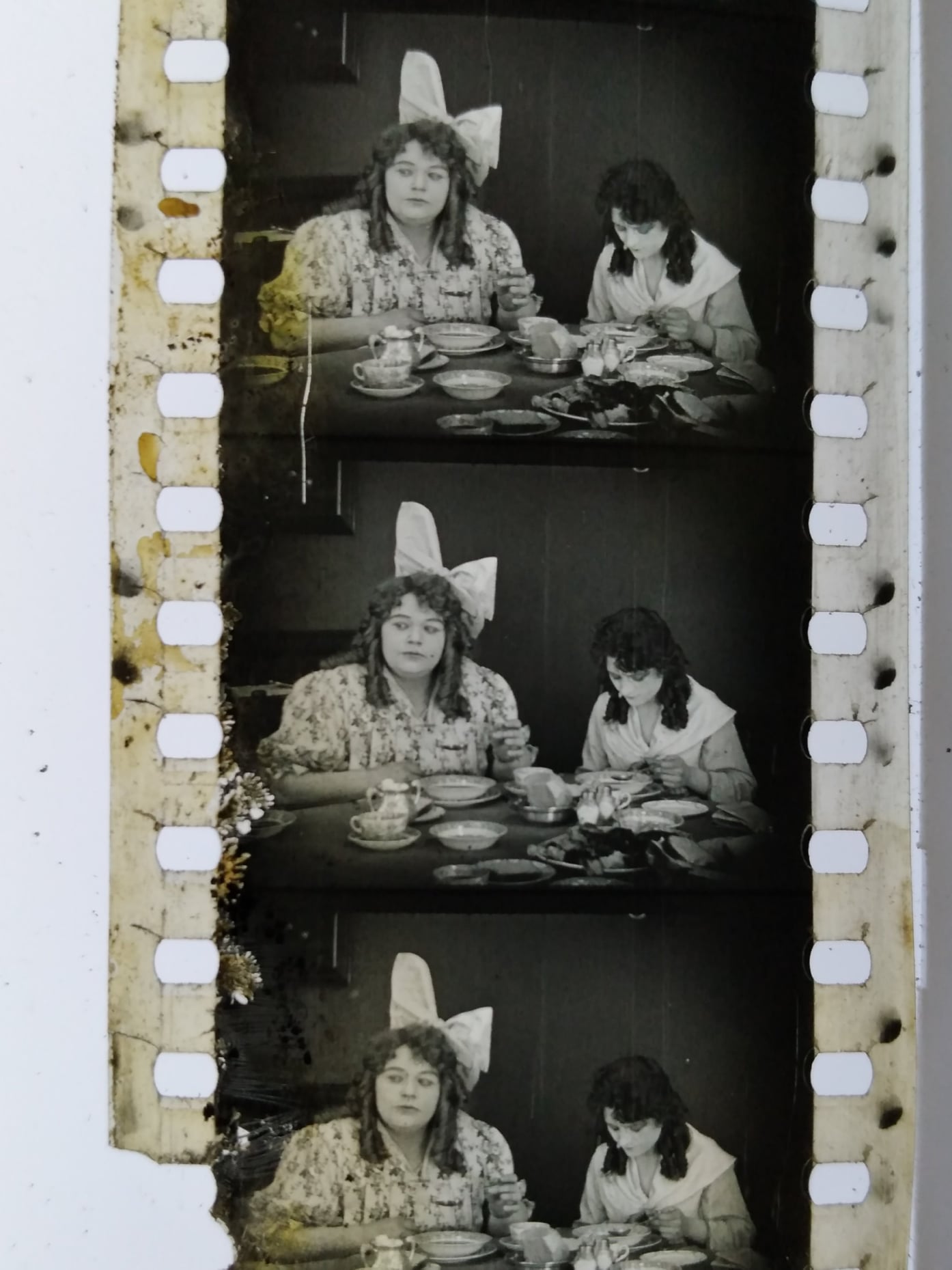

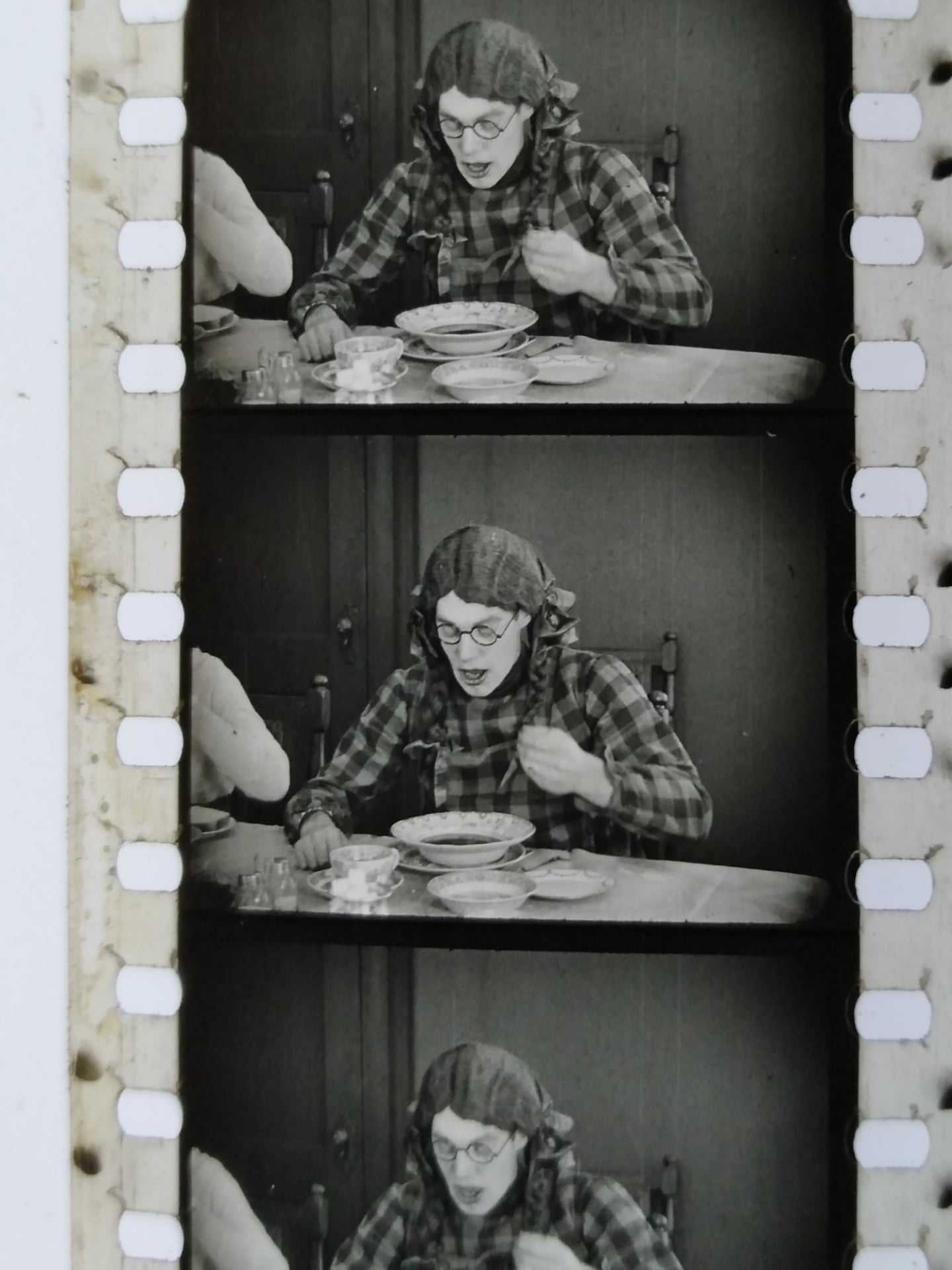

While Googling, I just found these three images,

which are from either an original April 1917 print of The Butcher Boy or the

February 1921 reissue.

Yes, these Arbuckle Comiques were among the exceedingly few films that were popular enough to merit reissues.

For what it’s worth, NBC broadcast a clip of this film in

April 1963,

and that indicates that this was one of the first Roscoe movies that Ray Rohauer collected.

It seems that he got a bootleg from France just prior to that broadcast.

The quality was appalling.

|

|

Look above, once again, at the list of recovered and missing films.

Do you see a pattern?

Buster did not keep copies of the films he had done with Roscoe Arbuckle.

Why would he?

He was a hired hand and though he assisted on the editing, Roscoe led the editing crew.

Buster did not keep copies of The Saphead or any of the eight shorts distributed by Metro,

namely The “High Sign” through The Goat.

Schenck’s contract with Metro probably forbade Schenck or his employees from maintaining any materials, even work prints.

Once that contract expired, Schenck’s new contract with Associated First National

probably allowed Buster to keep his work prints, and I assume that stipulation was added at Buster’s request.

That surely carried over to the MGM and United Artists contracts.

That must be why Buster kept copies of the bulk of the remaining films he did from The Play House

through Steamboat Bill, Jr.

(Unfortunately, some of these disintegrated.)

So, in sum, beginning with his distribution switch to Associated First National,

and then on through his remaining features for Joe Schenck,

Buster kept one or two work prints or preview prints of each of his films — except for four of the shorts:

The Frozen North, The Electric House, Day Dreams, and The Love Nest.

Why were those four shorts missing?

These are puzzlers, are they not?

You are again exasperated with me for pondering this trivial mystery.

Okay. But this pattern is trying to tell us a story.

I just don’t know what story it is trying to tell us.

|

“SC,” I assume, is “USC.”

|

|

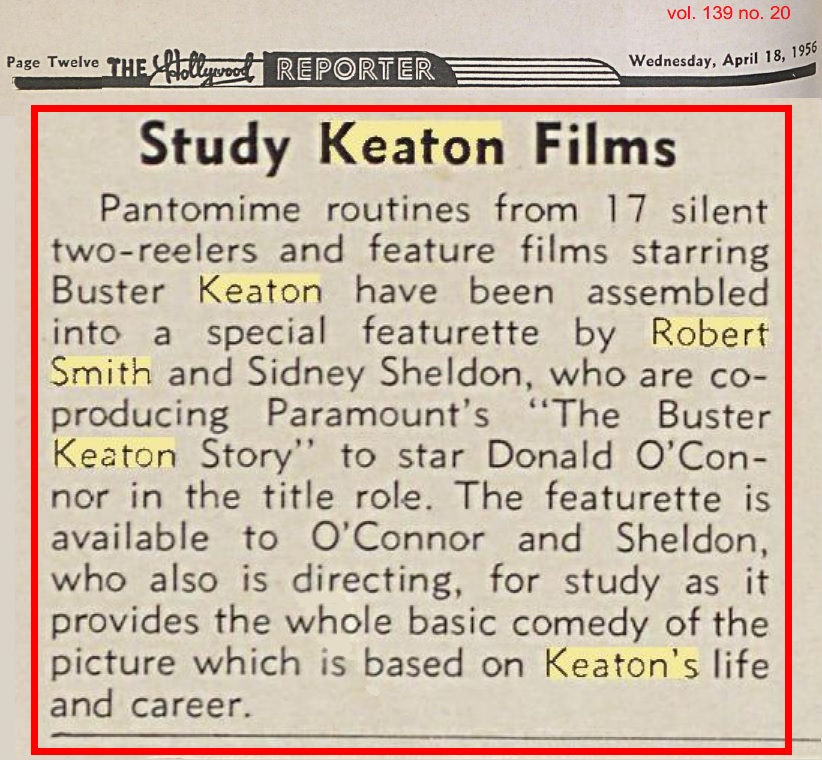

The above story about the sampler reels brings up an interesting point.

The sampler would allow Robert Smith and Sidney Sheldon to whittle down the selections

to, I think, eleven moments from Buster’s movies.

Once they had done their whittling, then Paramount would need to clear rights

only to eleven films, and probably not even the entire films, just those eleven moments.

Paramount had no interest — NONE, ZERO — in purchasing copies of any of the films,

for the simple reason that no copies would be needed for inclusion.

All those eleven moments would be freshly

|

|

Here’s another little particle of information about Loew’s/MGM filing copyright renewals.

Please take a look at John Schmitz’s article,

“Une rencontre avec Buster Keaton,” in Cahiers du Cinéma no. 86, August 1958, pp. 15–17.

We have only the French translation, which I am convinced is a rewrite.

I wish we had the raw English transcript, or, better yet, the original tape recording from 20 May 1958.

I do not trust some of the information contained in this translation, I mean, not even a little bit.

Nonetheless, it retains some useful information.

Schmitz asks Buster, “Do you have copies of your films?”

Buster responds,

“No. Joseph Schenck is the owner of all my old films.

MGM kept The Navigator and Sherlock Jr.

so that they could be shown on television, but that never happened.

The pictures are being blocked by shareholders.

Without their consent, they can’t be distributed anywhere.

If I had copies of my films, I wouldn’t hesitate to show them on television.

I’d be more than willing to challenge any of the groups that hold the negatives.”

Well, well, well, he did have copies, or, at least, Ray Rohauer held copies on his behalf.

Ray did not want them shown on TV, not until he cleared all the rights,

and he would spend the years 1954 through 1963 buying up those rights

so that he could issue the films himself, and Buster knew that project was in the works.

I don’t think Buster realized how long it would take to get the clearances.

Though Buster never goes so far as to direct his ire at Joe Schenck,

we can nonetheless detect that he was irritated with the guy,

or irritated with his lawyers and seconds-in-command,

and this is the one time, probably the only time in his life, when he let that show.

As recently as 1954, as we have seen, Buster claimed not to understand

why on earth anybody would be interested in a movie that’s forty years old.

Here, in 1958, he says that he wants his forty-year-old movies shown on television.

He has undergone a transformation.

Why?

The George Award for one thing.

The interest from MoMA for another.

Probably more than anything else, though, was the reaction from college kids

when Robert Smith and Sidney Sheldon showed them a dozen of his silents.

My educated guess is that it was that experience, above all else, that changed his mind.

|

|

The most suspect passage in this article is Schmitz’s remark:

“He hates to hear the audience laugh at screenings of his old silent films.

According to him, what provokes laughter is not outdated technology but faulty projection.

Old films are projected at a speed at least three times higher than that for which they were intended.

As a result, the actors seem to be convulsing instead of acting.

In the days of silent film, the camera recorded twelve frames per second for dramatic scenes and sixteen for action scenes.

The film was then projected at this speed. Talking films have a frame rate of 24 frames per second,

which cannot be changed due to the soundtrack.

Keaton assures us that with a device designed to slow down the projection,

the acting of the time would cease to seem archaic and appear to be the work of an expert.”

Uhhhhhh, yes and no.

Many silents, especially those from before 1922, really should be slowed down, but not to 12fps and rarely even to 16fps.

As you could hear when

George Pratt interviewed Buster in 1958,

Buster was talking about something different.

For dramatic scenes, cameramen tended to crank (or set their motors) at about 16fps,

though there was no law about that and camera speeds were all over the place.

As we can observe, for instance, in the Arbuckle films,

comedies were generally shot at slower speeds, 14fps or even much less.

This caused a comical speed-up in the action.

As a general rule, Buster was not a fan of cranking at slower than 16fps.

He did it when it helped, but for the most part he stuck to speeds that hovered somewhere around 16fps,

at least in his short films.

His features often employed faster camera speeds to match the projection speeds a little more closely.

Of course, even dramas were speeded up, too, because cinemas ran the projectors at speeds considerably faster than 16fps.

Buster made no mention of projection speed.

Interviewers never thought to bring up the topic, which is a pity.

So John Schmitz, or his editor, or his publisher, or his translator, put words into Buster’s mouth,

and that was such a horrible thing to do.

Buster complained when his feature films were slowed down.

Even for his earliest short films, he was okay with them being projected at 24fps,

though some of them were originally designed for slightly slower speeds.

Witness Ray Rohauer talking to Don McGregor in Buster: The Early Years

(Staten Island, NY: Eclipse Enterprises,

February 1982), p. 32:

“He was always very impatient to sit too long in the projection room,

particularly if we ran them at slow speed. He never wanted them run at 16 frames per second.

He always had to run them at 24 frames per second because he claimed that he shot all his films at 22 frames per second.”

The cue sheet for Three Ages demands a projection speed of 82'/min., which is about 22fps.

As we learned earlier, Buster originally showed The General at 24fps,

and some cinemas pepped that up a tiny bit.

The earlier shorts were definitely shot at slower speeds,

but the ones made beginning at about the start of 1922 were intended for a projection rate of about 24fps,

at which speed they raced, but they looked good when they raced.

Note especially the opening of The Paleface, which was shot at above 20fps,

and that is how we know that the intention was to project at 24fps.

Yet the rest of the film was undercranked, much of it quite severely.

Slowing it down even a little bit would wreck it.

See Ben Model’s piece on

The Goat and

look at this, too as well as

“Undercranking’s ‘smoking gun’ courtesy of Milton Sills”

and “Slow Motion Acting.”

Add to that this:

“undercranking clip: Keaton” and this:

“Undercranking Study: Buster Keaton Trails a Suspect”

You can add to that this horror: “Projection Speed-up Cited in 1915 Article.”

Ben penned some other important things, as well, for instance, his posting to

NitrateVille:

“There are studio-issued promotion sheets I’ve seen from the early ’20s

for several two-reel comedies that list the total footage and total running time...

in each case the math comes out to 24fps, from Pay Day to Sennett shorts

to Keaton’s The Electric House

[2,231'].

Comedians knew the films were run faster and used this to create gags

that couldn’t exist or be gags in real-time.

Mr. Brownlow sent me

an article he found in a 1927 Variety

describing how Murnau had seen Sunrise at a theater in NY

and was upset that it wasn’t being run at 100 feet per minute (27fps)

and had wired Wm. Fox about it.”

The misconceptions about the speed of projection for silent films have many sources.

From the beginning of the talkies, 16mm projectors had a SILENT/SOUND switch,

and the SILENT setting ran at 16fps.

That was not for regular movies, though.

That speed was for educators who could afford only 16fps cameras

and whose instructional films needed to be shown at the shooting speed in classrooms.

Then there was F.H. Richardson who, in his projection manuals,

insisted on projecting at camera speed.

In his earliest manuals, written in the nickelodeon days when many projectors were handcranked,

he insisted on speeds of about 16fps.

For handcranked projectors, that was about right, since slower speeds drop the fire shutter

and higher speeds make the machine wobble.

Once motors became commonplace, he still insisted on natural motion,

and yet it is certain that he was overspeeding films and thinking he was running at camera speed.

He most definitely was not projecting at camera speed. Far from it.

Clyde Bruckman, who was no technician, got things all messed up

when he granted an interview to Rudi Blesh for the Keaton bio.

He said that, throughout the silent era, projection speed was 16fps.

It most definitely was not.

He further said that the George Eastman House had adjustable speed.

It most definitely did not. (It did not install adjustable speed until about 1990,

and the techies got it all wrong but finally fixed it about a decade later.)

Then Joe Franklin muddied the waters in Classics of the Silent Screen (Bramhall House, 2 November 1959, $6.95), pp. 247–248,

in which he insisted that, shown properly, silent films have perfectly natural motion. Wrong!

Even now, audiences and museum projectionists and AMPAS employees and film programmers

and archivists remain terribly misinformed about the matter.

The modern projection speed of 24fps came into vogue right at the end of 1921,

in response to the new

Jim Card and Walter Kerr went to the other extreme.

They grew up in the 1920’s, by which time projection speed was most often somewhere around 24fps,

and so they insisted that all silent films be projected at 24fps.

Wrong! So totally, totally wrong.

Prior to late 1921, the projection speeds were usually slower,

and prior to about 1915, the projection speeds were usually a lot slower.

By the way, Ray’s above anecdote about Buster wanting the speed turned up

tells us that Ray was running the films with the speed turned down.

Apparently he set the switches on his 16mm projectors to the SILENT position.

It was a bit strange that he would do that.

I thought he would have known better.

|

|

Time for commentary.

The Buster Keaton Story was a work of purest fiction.

There is nothing wrong with a fictional work based on a real person’s life.

After all, The General is a fictional work inspired by an episode of William Fuller’s life.

More to the point, one of the world’s greatest movies is

a biopic of Franz Liszt that concludes with the composer piloting a rocket ship.

Fine.

My objection to The Buster Keaton Story is not that it was a work of fiction.

My objection is that it was a terrible work of terrible fiction, utterly puerile.

Had the script been written by an unintelligent eight-year-old it could not have been any worse.

Horrible movie.

Not as bad as The Deer Hunter, but that goes without saying, because no other movie is that bad.

It’s close, though.

It probably rates as a close second.

It’s worse than The Story of Mankind.

It’s worse than Long Pants.

It’s worse than Sidewalks of New York.

It’s worse than Free and Easy.

It’s worse than What – No Beer?

Much worse.

It would have been better had it concluded with Buster piloting a rocket ship.

It’s freely available online, but I cannot bring myself to watch it again.

It caused me physical pain when I saw it on

Sunday, 11 July 1982, at 11:30am on KLKK Channel 23 in Albuquerque.

Everything about it horrified me; it was terrible in every way.

Downright embarrassing to watch. Dreadful movie.

|

|

As horrible as the movie was, it was nonetheless most instructive.

Donald O’Connor and others in the cast did the routines and they performed the gags to technical perfection,

but all the routines and gags fell flat.

The routines were not funny. They never had been.

The gags were not funny. They never had been.

The routines and the gags had just been frames upon which to hang irony and the characters’ attitudes.

The stories were organic wholes.

A single situation, a single setup, a single gag, a single stunt isolated from the whole is meaningless.

The gags, the stunts, the illusions, the magic tricks are subsumed to the ironic narrative,

a narrative whose basis is the contemplation of the fundamental nature of reality,

and the conviction that reality is fundamentally absurd.

Devoid of the contexts, the

|

|

Sidney Sheldon told his version of what happened

here and

here and

here.

He condensed the story tremendously, and it seems he misremembered some things.

The part of his story that is completely convincing is Buster’s behavior.

Buster, I am sure, did not even read the script, and he wanted to contribute nothing apart from some recreations.

Sidney asked if he would like to change the script.

He asked Buster for stories, anecdotes, incidents, corrections, but Buster declined to say a word.

Well, he did say one single word, only one, several times over: “Nope.”

I can understand why.

After MGM and Sidewalks of New York, Buster simply had no confidence in such a studio product.

He decided to let the bosses do whatever they wanted to do and he refused to get upset about it, so long as he got paid.

In my opinion, that was a bad decision.

Sidney Sheldon was a good guy and he would have fought for Buster had only Buster fought for himself.

(I am reminded of Gore Vidal who inadvertently wrecked several of his own movies,

one after another after another, by his defeatist behavior.)

By another miracle, Buster’s bad decision paid some good dividends in the long run.

Had he made a good decision, he may well have had fewer lucky breaks afterwards.

|

|

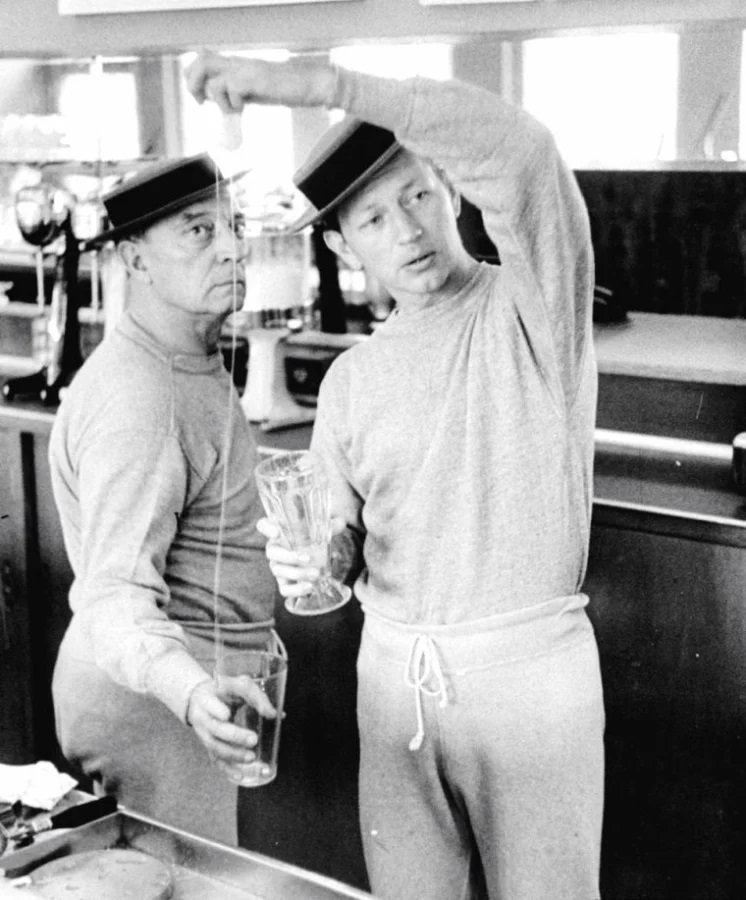

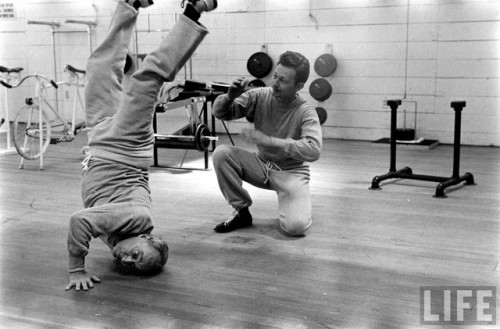

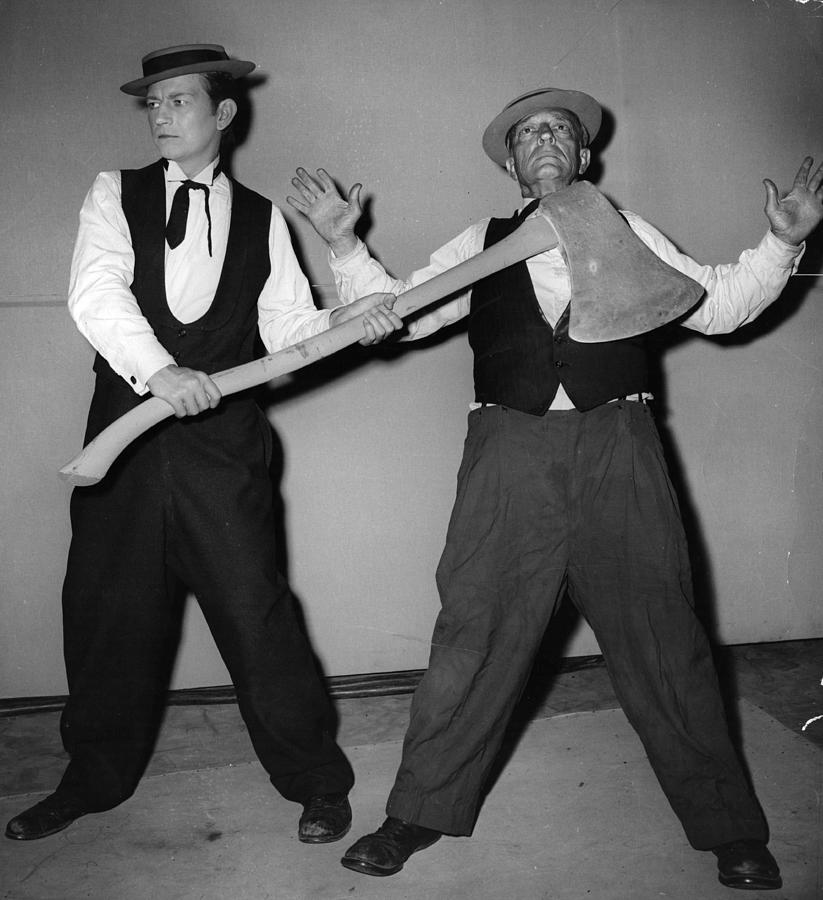

Buster and Donald seem to have been genuinely fond of one another.

The publicity stills, even the ones that were staged and posed,

reveal a real playfulness underlying the pretended playfulness.

Importantly, the candids are invaluable documentation of how Buster trained himself and his actors.

As far as I know, though Buster really

seems to have detested the movie,

he never spoke ill of it — well, not until years later when he was in Germany, as we shall see.

He was grateful for the income it brought him

as well as for the renewed recognition it brought him.

|

|

I guess making the movie was like a trip to the dentist.

You don’t want to go, but after it’s over, you’re glad you went.

|

|

It would have been better to do not a biopic, but a story about a Donald O’Connor character

who solves a problem by emulating a Buster Keaton movie he had seen in his youth.

Buster should have been called in to direct it.

The result could have been incisive instead of sappy.

|

|

I really like Sidney Sheldon and

I really like Donald O’Connor, but

Holy Mother of Moo Moo, their movie was brutal.

|

|

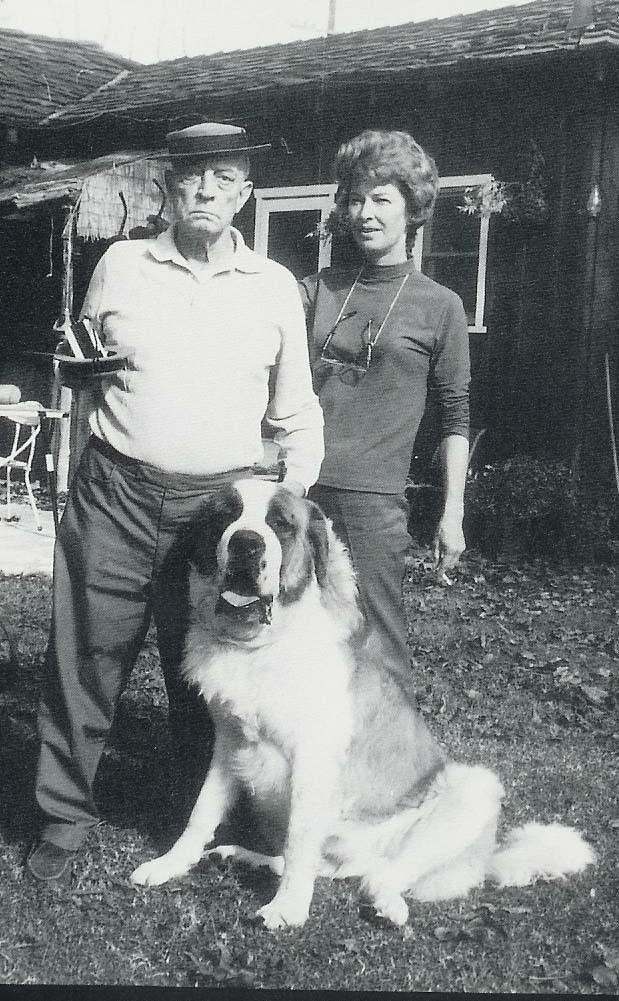

Brutal as it was, The Buster Keaton Story was a blessing in disguise.

Buster had lived through two decades of neglect.

Then, thanks largely to this rotten movie, he entered a final decade of laudits —

laudits bordering on worship.

Eleanor hated Sidney Sheldon’s biopic.

Everybody hated Sidney Sheldon’s biopic.

But if it weren’t for that sickening movie, Buster might now be nothing more than a footnote.

That movie was the best thing that could have happened to him, because it opened endless doors

and accidentally unleashed an ever-quickening cascade of opportunities.

It benefitted not only Buster, but every connoisseur of comedy and cinema.

It was almost certainly this wretched movie that brought sufficient attention to Buster

that the Academy Awards decided to bestow upon him an Oscar.

As much as I detest Sidney Sheldon’s unwatchably offensive biopic, I am grateful to it.

In the sense that it brought new fortunes to Buster and helped spur the Buster revivals,

it is, arguably, one of the most important movies ever made.

|

|

Buster had been a regular on TV since December 1949.

Almost certainly what brought him to TV producers’ attention

was James Agee’s article, “Comedy’s Greatest Era,” in

Life vol. 27 no. 10, 5 September 1949, pp. 70–82, 85–86, 88.

Walter Kerr’s article, “Last Call for a Clown,” in

Harper’s Bazaar vol. 85 no. 2886, May 1952, pp. 102–103, 156–157,

probably earned Buster a few more gigs.

Buster was really quite touched by those two articles, by the way.

Topping this off was the promotional work for The Buster Keaton Story.

That’s what got him on the

“Today” show on 14 September 1956 and on

“The Ed Sullivan Show” on 21 April 1957 and again on the

“Today” show on 23 April 1957.

And, in a sense, also on

“The Rosemary Clooney Show”

on 30 November 1956.

I cannot even guess if that promo work had anything to do with his appearances on

“Lux Video Theater: The Night of January Sixteenth”

(10 May 1956),

“Do You Trust Your Wife?” (19 June 1956)

“The Johnny Carson Show” (allegedly sometime in 1956),

“It Could Be You” (19 March 1957),

“Tonight! America after Dark” (24 April 1957), or

“Club 60” (2 May 1957).

Info about those episodes is pretty sparse.

The promo work was definitely responsible for the two appearances below, as you can see and hear.

|

|

|

The W/O/C Archive, This Is Your Life "Buster Keaton" - W/O/C - April 3rd, 1957, posted on Apr 30, 2021. When YouTube disappears this video, download it. |

|

Charles Samuels was horrified by The Buster Keaton Story.

It so upset him that he decided to set the record straight.

That is why he paid Buster for interviews that would become a book-length as-told-to autobiography,

My Wonderful World of Slapstick (NY: Doubleday,

21 January 1960, $4.50;

London: Allen & Unwin, June 1967, 30s).

That is another blessing that came about only in response to that offensive movie.

|

|

Bob Youngson, with a sense of humor even larger than his waistline,

edited together comical highlights of silent movies

into a Twentieth Century-Fox feature called

The Golden Age of Comedy,

released one month prior to The Buster Keaton Story.

It was a huge hit, though I don’t know why.

The left side was lopped off to make room for the narration and music,

and then cinemas, probably without exception, lopped off close to half of the height,

rendering the image and action meaningless.

Nonetheless, it was somehow a major hit, and it did much to get the public enthusiastic about silent comedy again.

There was not a frame of Buster in it, but still, it introduced 30-year-old comedy to people less than 30 years old,

who had never seen anything remotely like it before and who fell in love with it.

For his

|

|

There was a book as well.

The book would have happened with or without The Buster Keaton Story, of course.

On 2 November 1959, Bramhall House of NYC published Classics of the Silent Screen: A Pictorial History.

Joe Franklin signed himself as author,

but the copyright page states that the “research assistant” was one William K. Everson.

What I have heard for decades is that Bill Everson was actually the author of this book, not Joe Franklin.

Some of the text reads rather like Bill’s style, but by no means all, not even a little bit.

That’s not important.

What is important is page 186, in which the author wrote that the surviving Buster movies were:

The Haunted House,

The Balloonatic,

Cops,

Sherlock Jr., and

The General,

all available for viewing.

Also mentioned, with the implication that they still survived and were available for viewing, were

Our Hospitality,

The Navigator,

Steamboat Bill, Jr., and

The Cameraman.

A casual reader simply takes that as a statement of fact, namely, that those films were available as of November 1959.

I, on the other hand, am not a casual reader.

I saw that statement and, when I eventually managed to pick myself up off of the floor,

I tried to figure out how that could possibly have been the case.

Where were these films available for viewing?

That could only have been at MoMA, I think.

As we know,

The Balloonatic,

Cops, and

Steamboat Bill, Jr.,

had been recovered from James Mason’s property, and Mason donated them to the Academy.

MoMA, I guess, paid the Academy for duplicate negatives.

Perhaps.

Or perhaps the Academy donated them.

I assume that The Cameraman, or, rather, what was left of it, was donated by MGM

(to this day, there is a crucial three-minute segment that is missing).

The mention of The Haunted House surprised me, but it should not have, since it had been in the MGM vault all along.

|

|

Actually, I just now (October 2022) purchased Classics of the Silent Screen.

I had read it about twenty times back in 1973,

when my mother borrowed it from the

Hoffmantown branch of the Albuquerque Public Library.

This is the first time I have looked through that book in nearly half a century.

My heavens!

Now it comes together!

Now I can see where so many misinterpretations came from!

The idea that the characters of Buster’s leading ladies were all “dumb”

comes from this book and was repeated everywhere.

Actually, they were all quite clever, not “dumb” in any way.

Ofttimes they found themselves in situations in which they were out of their element, but they came through, always.

This is the book that described Buster’s character as “unemotional” and “defeatist,”

which is absolutely contrary to the character he portrayed on camera.

It’s all so strange, isn’t it?

|

|

Another mind-boggler:

Ben Davis in his book on

Repertory Movie Theaters of New York City (Jefferson, NC: McFarland, 2017)

states something astonishing on page 26.

Dan Talbot of the New Yorker Theatre ran The Play House and The Boat in 1960!

They had to have been cropped 16mm prints and they could only have come from Rohauer.

|

Stan Brakhage |

|

Are you familiar with Stan Brakhage?

Very famous maker of abstract films, for instance this.

In his book, Film Biographies (Berkeley: Turtle Island, July 1977, pp. 181–182),

he told a story that’s worth retelling.

|

|

I was living in Los Ángeles; and I went often to The Coronet

Theatre to see old cinema classics, etc. One night a friend

and I took ‘pot luck’ on whatever The Coronet might be showing.

We were disappointed, on arrival at The Theatre, to discover

‘the show’ for that night was a ‘twenties’ comedy by an

unknown, to us, comedian named Buster Keaton.

We went ‘in for it’ anyway but sat in the back so that we

could easily leave. The title “Steamboat Bill, Jr.” flashed on the

screen; and the first long camera ‘pan’ across an old river town

had my friend and me fidgeting.

But soon some jokes came along to humor us. The gags of

‘The Father’s’ disgust at the sight of his ‘Son,’ played by Buster,

called forth more than usual laughs from me. I’d just been

recently to see my father and had ‘had it,’ the same kind of

reception.

My friend was ‘taken by’ the “Romeo and Juliet’-like

development of the plot, he being involved with “influences of

Shakespeare on our times’ or some-such.

We were ‘guffawing’ along with the rest of the audience

and began, then, to notice a man, sitting in front of us, who

never once laughed. We even made ‘raised eyebrow’ expressions

at each other about it, ‘shrugs of shoulder’ and the like.

Then came the cyclone sequence in the film. A whole town

blows up and down around the hero, buildings falling and narrowly

missing him, etc.; and ‘the house came down’ within The

Theatre, too, everyone laughing more than I’d ever heard before,

myself and friend laughing uncontrollably. When we had time

to notice, between absolute fits of giggling, we saw the man’s

shoulders in front of us rigid as ever, not so much as a tremor of

laugh moving him. We became as amazed by this mysterious

stranger as we were by “Steamboat Bill, Jr.”. Toward the very

end of the film, the man in front got up and turned to leave;

and it was, of course, Buster Keaton.

|

|

To make sense of Stan’s story, we need to pinpoint the date,

and, since the Coronet did not advertise or announce its shows in the newspapers, that becomes a difficult task.

The one time I heard Stan Brakhage speak was on

Saturday, 26 January 1980,

at the SUB (Student Union Building) screening room on the UNM campus,

where he introduced five of Buster’s short films and took questions afterwards.

An audience member asked him when Buster was born, and Stan didn’t know.

He said that he never paid any attention to dates. None.

It seemed that he didn’t know the difference between 1820 and 1940.

It was all the same to him.

He explained that he refused to memorize anything he could just as easily look up.

Someone blurted out that Buster was born in 1895,

and Stan was thankful that someone volunteered to answer the question for him.

(Actually, now that I think about it, I’m the one who blurted that out.)

|

|

It is likely that Ray Rohauer had a 16mm print of Steamboat Bill, Jr. as early as the summer of 1954,

copied from the decayed nitrate in Buster’s garage.

We know that James Mason recovered Steamboat Bill, Jr., in the spring of 1955.

Ray probably paid General Film Laboratories to make a 35mm preservation negative immediately.

Question: When did Stan’s story take place?

He remembered that it was sometime between 1955 and 1957.

I had thought that impossible, but now that I have more information, I see that it fits perfectly.

It had to have been 1957, which is when the copyright to Steamboat Bill, Jr., expired.

In earlier drafts I wrote that Stan lied.

He did not lie.

He told the truth.

|

|

When we check on Stan’s dates, we discover that

he was employed at the Coronet in 1956 as

a projectionist and

janitor

in exchange for room and board, and, yes, there were living accommodations in the Coronet Theatre building

(just as there were at the Movie: Old Time Movies on Fairfax).

|

|

Elsewhere, Stan elaborated.

When I first read his account, I scoffed at it as the most patently obvious confabulation

by someone who was trying to get attention.

Now I discover that, yes, he was telling the truth.

Take a look at

“Stan Brakhage Dialogue with Bruce Jenkins, 1999”

(I corrected a few of the more bothersome typos):

|

|

There’s another piece of fantastic luck. That I should be the janitor when Rohauer is getting these films, the rights to

them and getting them transferred out of nitrate into safety film, which he did because MGM [sic] wanted to do The

Buster Keaton Story. One of the lousiest films in the whole history of Hollywood, Donald O’Connor trying to play

Buster Keaton. I was there at these meetings just tagging along with Raymond and Keaton. They’d have these

conferences and Keaton was like what do you call it? He was like reference. What do I mean here? He was the

authority on himself.

O’Connor is sitting there and saying, “Well, in that film The College, how did you do that trick where you turned

somersault and kept the coffee intact, didn’t spill the coffee?” Keaton, who at this point is —

God, he was in his 70’s — he

said, “Kid, I can’t do it like I did it then.”

He said, “But I’ll show you a trick, a way you could probably do it.” Then he did

right in front of us this somersault, and he slipped this thing onto a table and picked it up so quickly you could hardly

see. You could have cut three frames out of the movie and you’d never see that it hit the table at all and did this

somersault like that, and ended up with the thing intact and everyone just sat.

|

|

The Buster Keaton Story was filmed in 1956 and released in April 1957.

Rohauer’s involvement in The Buster Keaton Story

was simply to supply the films to Robert Smith and Sidney Sheldon in about March 1956.

That was all.

Interesting to learn that Ray and Stan witnessed any story conferences.

|

|

Stan’s story about witnessing an unlaughing Buster in the Coronet auditorium has the ring of truth to it,

but I was unaware of any possibility of seeing Steamboat Bill, Jr., at any time in the 1950’s,

and so, yet again, I dismissed his account.

Also, I was certain that Buster would have had Eleanor by his side, a detail that went missing from Stan’s telling.

Eleanor denied that she and Buster were at the Coronet

except for that one evening to see The General.

Yet now I learn that, yes, Buster did attend screenings without Eleanor.

Every detail I had scraped together that proved Stan was a liar has now been proved wrong,

and so I have done a 180° on that subject.

I now trust Stan implicitly and I shall accept anything he said.

He has demonstrated his reliability.

|

|

Keep on reading the rest of “Stan Brakhage Dialogue with Bruce Jenkins, 1999,”

because the stories continue, with more details that I found worse than implausible

but that I now accept totally.

|

|

Stan and Ray were friends, but soon enough, most likely because Ray Rohauer was Ray Rohauer, they became enemies,

or something resembling enemies.

Decades later they had some sort of

hesitant rapprochement, but I don’t know the details.

I wonder if Stan ever chatted with Buster at all.

If not, that would not surprise me.

After all, read his chapter on Buster,

and you will discover that his encounters with Buster, which should have remained vivid, were vaguer than vague,

so vague, in fact, that it seems they never exchanged a word.

This is all very curious, yes? No?

|

|

Stan’s anecdote about the unlaughing Buster in the audience completely matches a story told by Bob Olds:

|

|

Ben Model - silent film accompanist/historian, interview by Ben Model w/Bob Olds, who directed Buster Keaton in a 1959 commercial, posted on Oct 4, 2021 When YouTube disappears this video, download it. |

Case Closed |

|

Before we conclude this web page, let us go back to Jim Curtis’s book.

Buster Keaton Productions, Inc., had been established as a New York corporation.

Now, in 1958, Ray, with Kristian Chester and Buster, established a different Buster Keaton Productions, Inc., as a California corporation.

Though commentators have tried to make this look absolutely sinister, there was nothing remotely dishonest or deceptive about this.

It was perfectly legal for a California corporation to bear the same name as a New York corporation —

especially since the New York corporation had long been defunct.

|

|

For the record, the original

Buster Keaton Productions, Inc., was formed in New York on 23 January 1922, #103832.

The incorporators were David Blum, Harry Bernstein, and Mattie Hammerstein, all of 1540 Broadway, Manhattan, NY.

As of 10 May 1923, it was qualified to do business in California.

It forfeited its qualification to do business in California on 6 January 1941 for failure to pay franchise tax.

It was dissolved in New York on 15 December 1944, by proclamation, for failure to pay corporation taxes for three years.

Leopold Friedman, one of the original trustees, then became

“Trustee in Liquidation of the Assets of Buster Keaton Productions, Inc.”

I suppose that the naming of a trustee in liquidation

would indicate that BKP had declared bankruptcy at one time and still had debts to pay.

I find it a bit odd that a founding trustee was appointed to be trustee in liquidation.

Was that a conflict of interest? Were the debts, perchance, owed only to the Schenck brothers?

Finance, to me, is a foreign language.

|

|

The new Buster Keaton Productions, Inc., was formed on 24 September 1958 in Los Ángeles County.

The directors were Raymond Rohauer, Kristian Chester, and Buster Keaton.

By election of Buster Keaton to the office of president and Eleanor Keaton to the office of secretary,

Buster Keaton Productions, Inc., would be dissolved four years later, on 8 October 1962.

|

|

Now that Ray and Buster were partners in Buster Keaton Productions,

Ray, in October 1959, arranged to borrow AMPAS’s print of Cops,

which he received probably in early November and immediately duped.

That was the first item he ever borrowed from AMPAS. See page 611 of Curtis’s book.

Then, on 31 December 1959, Ray asked to borrow the nitrates of The General and Our Hospitality.

On 29 January 1960, Ray responded that Our Hospitality was badly deterioriated and that not all the reels were usable.

He returned The General and Our Hospitality and asked next for prints of

The Saphead, The Navigator, and Sherlock Jr.

A significant point that Jim Curtis makes here is that this was the beginning of Ray’s collection of Buster films,

and that it began at the end of 1959 and continued into the early months of 1960.

That is an excellent point, and an important one, and I am thrilled to have that information at my fingertips.

I was hoping for more details about each of the other prints that Ray borrowed, and when he borrowed them,

but nothing more was included in Curtis’s book, I presume because he didn’t know.

|

|

Then Olga Egorova pointed something out to me.

There was a pattern here, and I had entirely missed it.

It was in late 1959 and early 1960 that Ray asked AMPAS for Buster movies

that were readily available from MoMA and at least one 16mm supplier.

So, Ray’s requests do not indicate that this was the beginning of his Buster collection, but the final stage of it.

When he first got his hands on the films in Buster’s garage in the summer of 1954

he made a 35mm preservation negative of at least four of the six reels of Three Ages,

and he made the cheapest possible

|

|

So, we can see that once he had the rarities in hand,

he concluded his work by copying the films that were not in danger of being lost:

Cops, The General, Our Hospitality, The Saphead,

The Navigator, and Sherlock Jr.

|

|

With that final insight, as far as I am concerned, the case is closed.

Ray had or had access to several Buster movies in 16mm at least as early as September 1950.

In 1954, he rescued two or three of the six or eight decayed films from Buster’s garage,

but it seems he copied them only to 16mm, badly.

In 1955, he rescued as much of James Mason’s collection as he could,

paying General Film Laboratories to make 35mm preservation negatives,

but he did not finish his work in time, and the films,

including the few that he had not duplicated, were donated to AMPAS.

In 1959 and 1960, he finished the job, borrowing the remaining items from AMPAS and copying whatever was still usable.

|

|

For the sake of fairness, I should mention that I met Jim Curtis and his wife

when we ended up sitting next to each other at one of Miles Kreuger’s get-togethers,

and we chatted a bit and I liked them.

I’m sure they don’t remember me.

I had no idea that Jim was working on a Buster bio.

Had I known that, I would have showered him with info.

Oh well.

Here is a little article you should read:

Peter Larsen,

“Buster Keaton’s Life, from Silent Film Stardom to ‘How to Stuff Wild Bikini’

Gets a Fresh Look,” The Orange County Register, Thursday, 21 April 2022.

Larsen also chatted with Melissa Talmadge Cox,

whom I have not seen in 20+ years and whom I would love to chat with again,

as well as Bobbi Shaw Chance, whom I would give my right arm to meet.

In this article, Melissa and Bobbi provide a context I never had before.

|

|

Buster Keaton Rare Interview Recording

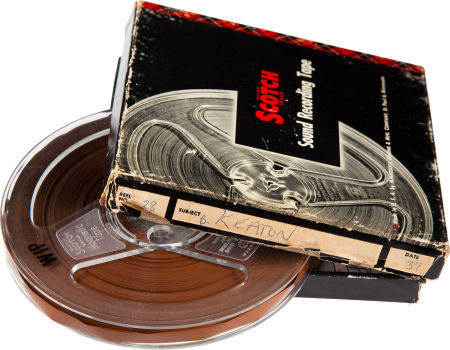

Regarding The Buster Keaton Story (1957)  Sold on 14 November 2010 for $298.75. Had I only known about this, I would have placed a bid. Who has this tape? I would happily pay to get a copy. |

|

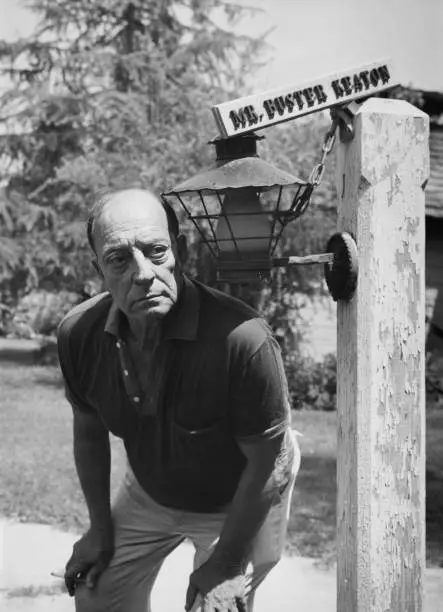

Paramount Pictures previewed The Buster Keaton Story on

7 April 1957 and premièred it in NYC

ten days later.

Buster steeled himself against the pain and agreed to do his contracted promotional work for it.

Ironically, The Buster Keaton Story, a dreadful flick that

did average business at best and that has mercifully been forgotten,

put Buster back into the limelight.

The money he earned from that movie bought him the

little ranch house at

22612 Sylvan Street in Woodland Hills.

He had dreamed of such a place since his youth.

He was now a hot commodity again.

Everybody wanted to hire Buster.

|