The Coronet Theatre |

|

This is a tangent, and yet it is crucial to understanding Buster Keaton’s career,

even though Buster only rarely stepped inside this building.

|

|

The Coronet, 272 seats, was built in 1947 and presented both occasional live entertainment but mostly films.

The schedules embedded below give me the distinct impression that the Coronet presented 16mm only, never 35mm.

Film screenings had to go on hiatus for a few weeks or months whenever a theatre set occupied the stage.

Paul Ballard, who had run his Film Society out of his apartment,

moved his program to the Coronet and redubbed his organization

the Hollywood Film Society.

He began his Coronet film series on 5 May 1947.

To read a little bit about and by Paul Ballard, click

here and

here and

here.

I was able to take snapshots of the programs, and, yes, this is probably the complete collection.

|

|

If this does not display,

download it.

|

|

It seems to me that most or all of the films came from MoMA.

My guess is that Raymond Rohauer was involved in this from the earliest days,

and I guess that because Paul’s and Ray’s programming was so strikingly similar.

I cannot be certain of Ray’s involvement in Paul’s organization, though.

|

|

A month after Ballard’s film series opened,

the Coronet opened its first stage presentation,

Thornton Wilder’s The Skin of Our Teeth on

Wednesday, 11 June 1947.

Its second stage production was the world première of Brecht’s Galileo on

Wednesday, 30 July 1947.

|

|

For some background, you can read the Los Ángeles Department of City Planning’s

RECOMMENDATION REPORT

for the Cultural Heritage Commission.

It’s a good read with a good history.

|

Raymond Rohauer |

|

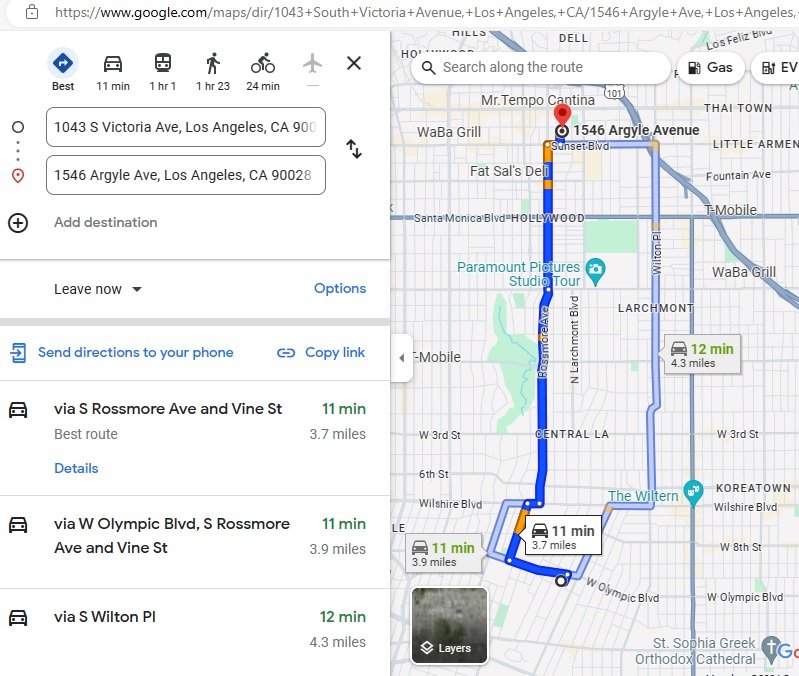

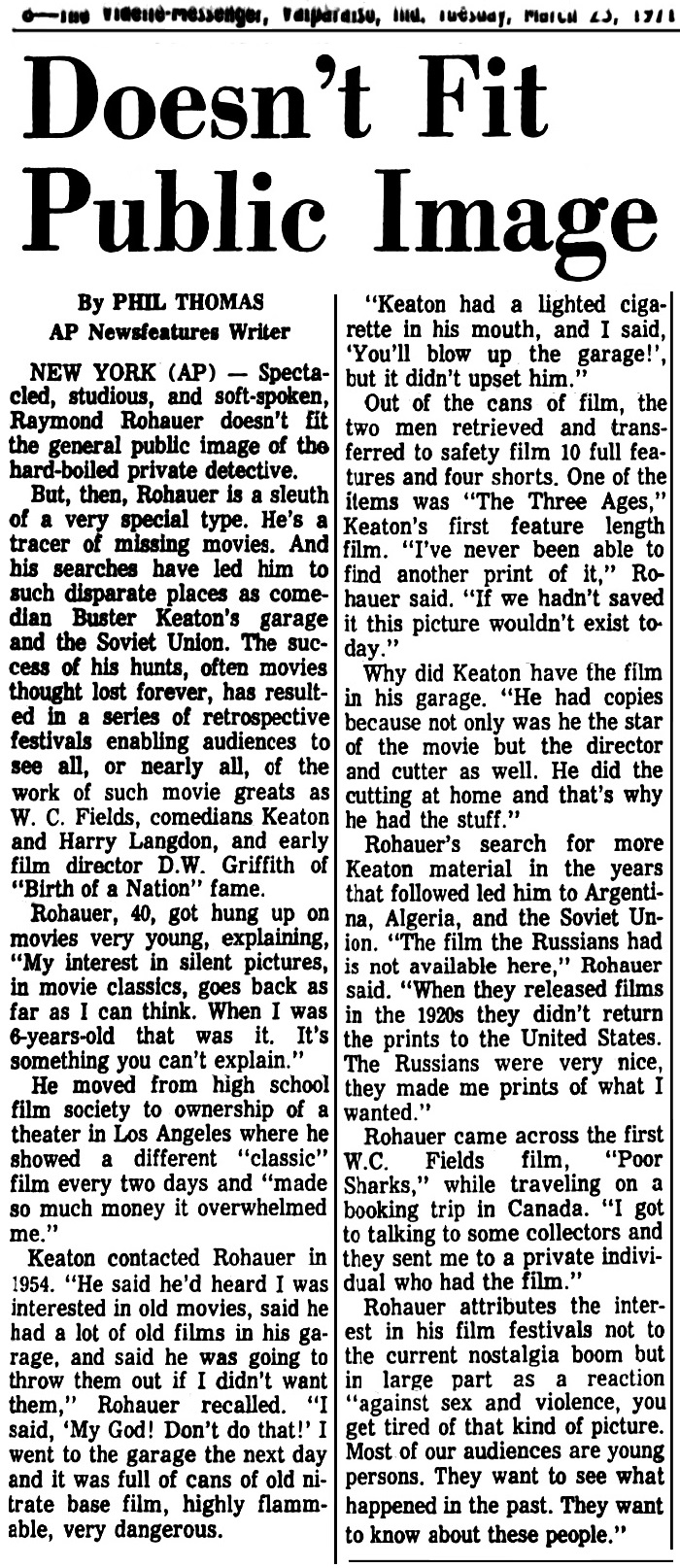

You are about to start running into lots of mentions of a certain Raymond Rohauer.

As an introduction, here is a little video.

It is inaccurate, but it will give you a pretty fair idea

of the Commonly Accepted Knowledge concerning this certain Raymond Rohauer.

And remember: Commonly Accepted Knowledge is usually wrong.

|

|

OddityArchive, Oddity Archive: Episode 208 — The Ballad of Raymond Rohauer, posted on Dec 10, 2020. When YouTube disappears this video, download it. |

|

You would be hard-pressed to find anybody to offer a complimentary word about Raymond Rohauer.

In my personal experience, the opinions of those who knew him, met him, dealt with him, or even just learned about him,

are almost entirely disparaging.

Now, I have been taking time off to plough through holdings at an archive,

where I am promised tons and tons of dirt on this certain Raymond Rohauer.

As I dig through the holdings, I am finding exactly no dirt on Rohauer.

None. Zero. Zilch. Nada.

The bulk of the horror stories I have read and heard through the years are dissolving before my very eyes,

dissolving into nothingness.

I am finding lots of unsavory information, though, about his critics.

|

|

Now, Rohauer was no angel, and he was certainly peculiar, borderline psychopathic.

He was manipulative and deceptive.

He could be really nasty at times and he had some bizarre quirks.

The result was that, as far as I know, he had no close friends, save one Kristian Chester.

From what I can gather, most people just wanted to get as far away from him as possible.

His alterations of the films under his care irk me no end and I consider those changes to be sheerest vandalism,

and yet I understand the paranoia that led him to commit those atrocities.

Ray Rohauer also had a proclivity for massaging a true story to make it reflect upon him better.

Sometimes he invented episodes out of whole cloth, and in such stories he emerged as the valiant hero who saved the day.

On the other hand, as for all the evil that is supposedly lurking in the background, well, it ain’t there.

So, please be careful.

As for the calumnies I have scribbled onto the various pages of this website, well, I apologize.

I shall scrub them away over the next couple of weeks.

For the record, yes, Ray Rohauer did indeed copy some of the films he rented from MoMA or other distributors,

but not in order to present pirate programs.

That was just his private compulsion to build a personal collection, not for public consumption.

When he ran shows at his cinemas, he rented prints and paid the fees and royalties.

He did something else, though, something that drove everybody crazy,

something that aroused hatred and indignation everywhere,

something that will earn him a favored spot in history as the centuries drag on.

I say it elsewhere and I say it here again:

History will be kind to Raymond Rohauer.

|

|

Rohauer had established the Memorable Films Society no later than December 1947.

Either through a name change or a reorganization, this evolved into the Society of Cinema Arts no later than June 1948,

and he arranged screenings in various venues.

|

|

After Paul Ballard’s Hollywood Film Society left the Coronet,

live performances continued as before, still under the sponsorship of John Houseman’s Pelican Productions.

In January 1950, Rohauer revived the Coronet’s film series, this time under the aegis of his Society of Cinema Arts.

|

|

The SCA concentrated largely on experimental,

|

|

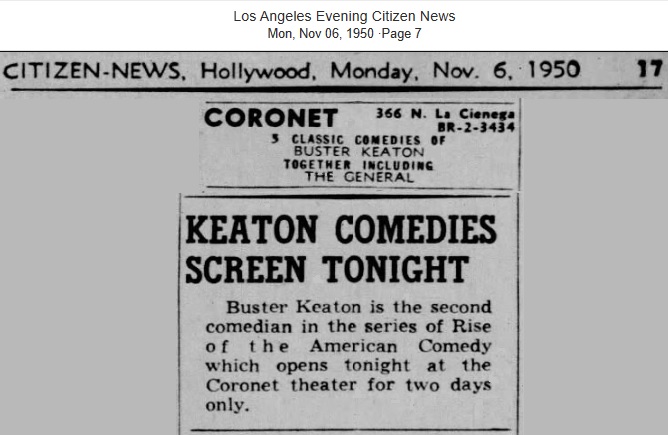

The Coronet was

16 blocks from John and Dorothy Hampton’s Movie: Old Time Movies.

Artsy places need to be in Bohemian neighborhoods,

and yet these two movie houses were rather out of the way in the antiseptic suburbs.

Surprisingly, they each somehow attracted a loyal clientèle.

That would seem impossible, and yet it happened.

|

|

Just discovered a thesis by Micah Isaiah Gottlieb entitled

The Past and Future of Alternative Moving-Image Exhibition in Los Ángeles from 2021.

Gottlieb maintains that Ray Rohauer insisted

“on building and screening from his own personal archive of prints”

and that this “was both unprecedented and illegal.”

Predictably, there is no source for that assertion.

|

|

Now, I had searched and searched and searched and searched and searched

for months and months and months and months and months

in all the available LÁ periodicals

for any advertisement, any announcement, of Rohauer’s programming at the Coronet — all to no avail.

There was the occasional passing reference, together with plenty of items about the stage shows,

and, of course, articles about the vice squad raiding the place (for two films that displayed no vice),

but there was nothing about the film programming.

|

|

The two movies that were busted?

Fireworks and

The Voices.

They leave me totally cold and I find them hopelessly dull, but some folks like ’em, so hey.

Did you click on the links and watch them?

Did they scandalize you?

Did they corrupt you?

Were they pornographic?

Did they lead you down path of perdition?

There is a widespread accusation that the Coronet was popular among “homosexuals.”

True, but what of it?

See, for instance, Queer Maps,

which devotes a page to the Coronet.

The problem with pigeon-holing the Coronet as a queer hangout is simply that the same holds true for any place that exhibits fine arts.

The artistic crowd tends not to give a hoot about people’s hormonal balances,

and so it’s a crowd that can serve as a good refuge for those who wish simply to unwind and be themselves.

The implication that the Coronet was a hotspot for perverts was preposterous.

Please, folks, please stop saying that, now.

(I use quotation marks because the word is an adjective, not a noun, despite popular usage.)

How is this summarized in the mainstream media?

Here is John Baxter’s assessment, published in The Sunday Times Magazine, 19 January 1975, p. 32:

“In October 1957 the police swooped on the Coronet

and arrested Rohauer for exhibiting a number of pornographic homosexual films.”

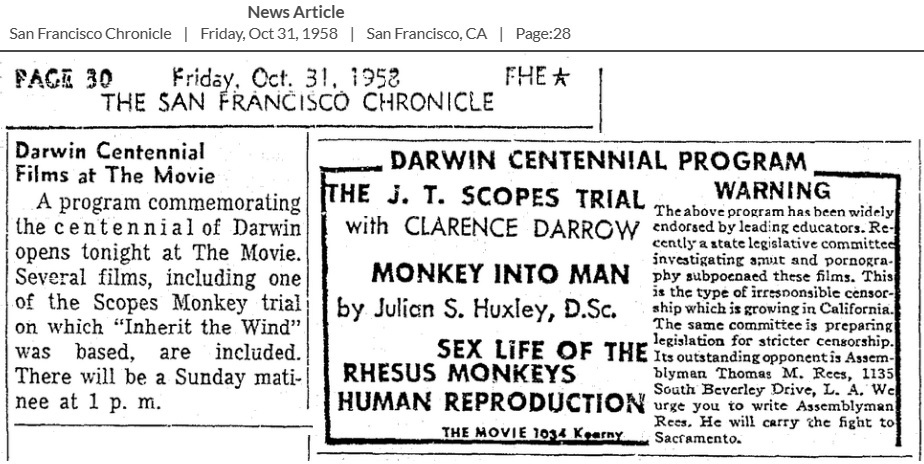

Curiously, the State Assembly Subcommittee on Pornographic Literature

got Ray into legal trouble, yet again, for showing “lewd movies” and “smut.”

The movies in question:

Monkey into Man,

an educational film from 1938, by Strand Film Zoological Productions Giving the Rorschach Test: Klopfer Method, a health-education film from 1951, produced by the City College of New York Human Reproduction, from 1947, part of Sex Life of the Rhesus Monkey, an educational film distributed by Pennsylvania State University; I suspect that the correct title was Social Behavior of Rhesus Monkeys from 1947, part of the “Clarence Raymond Carpenter Primate Studies” series offered by Pennsylvania State University’s Psychological Cinema Register Birth of a Child, which I am unable to identify; there is a description in the scrapbook below; if you can identify this film, please contact me; thanks! Experiments in the Revival of Organisms, distributed by the Un chien andalou, the repulsive and boring but popular Buñuel/Dalí silent from 1929 El, Luis Buñuel’s 1953 thriller in general release through Columbia Pictures.

That’s pornographic????? That’s lewd smut?????????? Gimme a break.

The controversy above led to support in San Francisco:

|

|

Anyway, the utter lack of publicity convinced me that the Coronet must have been a private club that never advertised.

What I did not realize was that there was one newspaper, probably only one,

that accepted advertisements for and press releases from Rohauer’s screenings at the Coronet.

Well, that changes my story, doesn’t it?

This was a newspaper I had never heard of before, the Los Ángeles Evening Citizen News.

But the advertisements and press releases ceased after a mere few months.

A second newspaper, the Daily News, also made a few rare mentions of Rohauer’s programming,

but I had never caught them before, surely because the paper had not yet been fully OCR’d and indexed.

|

|

So, here we go. Below we have the beginnings of a scrapbook.

It is a scrapbook in progress.

It may never be complete.

As I find more, I shall add more.

It consists of items dealing mostly with Ray Rohauer and with the Coronet Theatre.

I included other items, such as movie ads that mention neither Rohauer nor the Coronet,

but I include them only for the sake of context.

Use the scrollbar or the mousewheel on the below window to go through the various clippings.

|

|

If the above scrapbook does not display,

download it.

|

|

Might you have any Coronet-Louvre / Society of Cinema Arts programs in your collection?

If so, please let me know.

I shall happily pay for scans, which I would like to post here.

I have seen only a few, poor thermal photocopies of poor thermal photocopies,

and further copying is strictly forbidden.

|

|

What was Raymond Rohauer’s great offense?

What did he do that made everyone so angry, indignant, resentful?

From his teen years, he did the same thing that John Hampton did.

He started collecting 35mm nitrate film, rejects that he claimed to have found in attics and basements.

Yes, that is where films could be found.

Heck, they could even be found in newspaper classifieds.

|

|

Many of these films were commonly believed to be in the public domain,

but the public domain is a tricky topic.

Though a film can be in the public domain in the US, it might not be in the public domain elsewhere in the world.

Further, even if the film is truly in the public domain, it could be based on underlying works that still have valid copyrights.

Rather than risk breaking the law, Ray Rohauer set about searching high and low for anyone who might control the underlying rights.

He found elderly widows and descendants who had not even been aware that they owned these properties.

He drafted contracts by which they would either sell him their rights or license those rights to him.

So, other companies and various museums who thought they owned films

suddenly found themselves confronted by a peculiar nebbish

who waved copyright registrations in front of them and threatened them with suit if they continued to hold screenings.

That is why everybody hated his guts.

|

|

At the Margaret Herrick Library in Beverly Hills,

you can request a pair of file folders donated by Anthony Slide,

both dealing with Raymond Rohauer.

Inside are photocopies of a two-part interview published in a tabloid called MARBLE.

I have searched but can find no reference to this periodical anywhere.

At the top of one of the pages is a section subheading:

“Film News and Comment.”

Evidence in these photocopies indicates that this was a local New York City

publication,

|

|

Since this publication is so exceedingly rare and unavailable in any library,

I shall take the risk of reproducing the text portion of the interview in full.

If you own the rights to this article,

just drop me a line and we’ll make things right.

|

|

MARBLE [July/August 1975] Film News and Comment

Presenting Raymond Rohauer...

By Scott Isler

Ask various people in the film business

about Raymond Rohauer and their

comments most likely will range from the

complimentary to the slanderous. The

public, if it is aware of him at all, is

probably most familiar with the

“Raymond Rohauer presents” title cards

that linger on the screen at the beginnings

of the old films he circulates. His name is

there because Rohauer owns the rights to

those films, most of which were made

before he was born. This seems to be what

some people hold against him: a resentment

that he is making money from the

work of others, despite the fact that

without his diligence, many of these films

wouldn’t be available at all.

Rohauer, a likeable, conservatively-dressed

figure, describes himself as a film

collector but uses a very exclusive

definition. “Real film collecting is getting

an original copy of something,” he

maintains. “Film collecting is not buying

prints. Anybody can collect films by going

around from store to store and buying

them but real collecting is almost a

finished art now.”

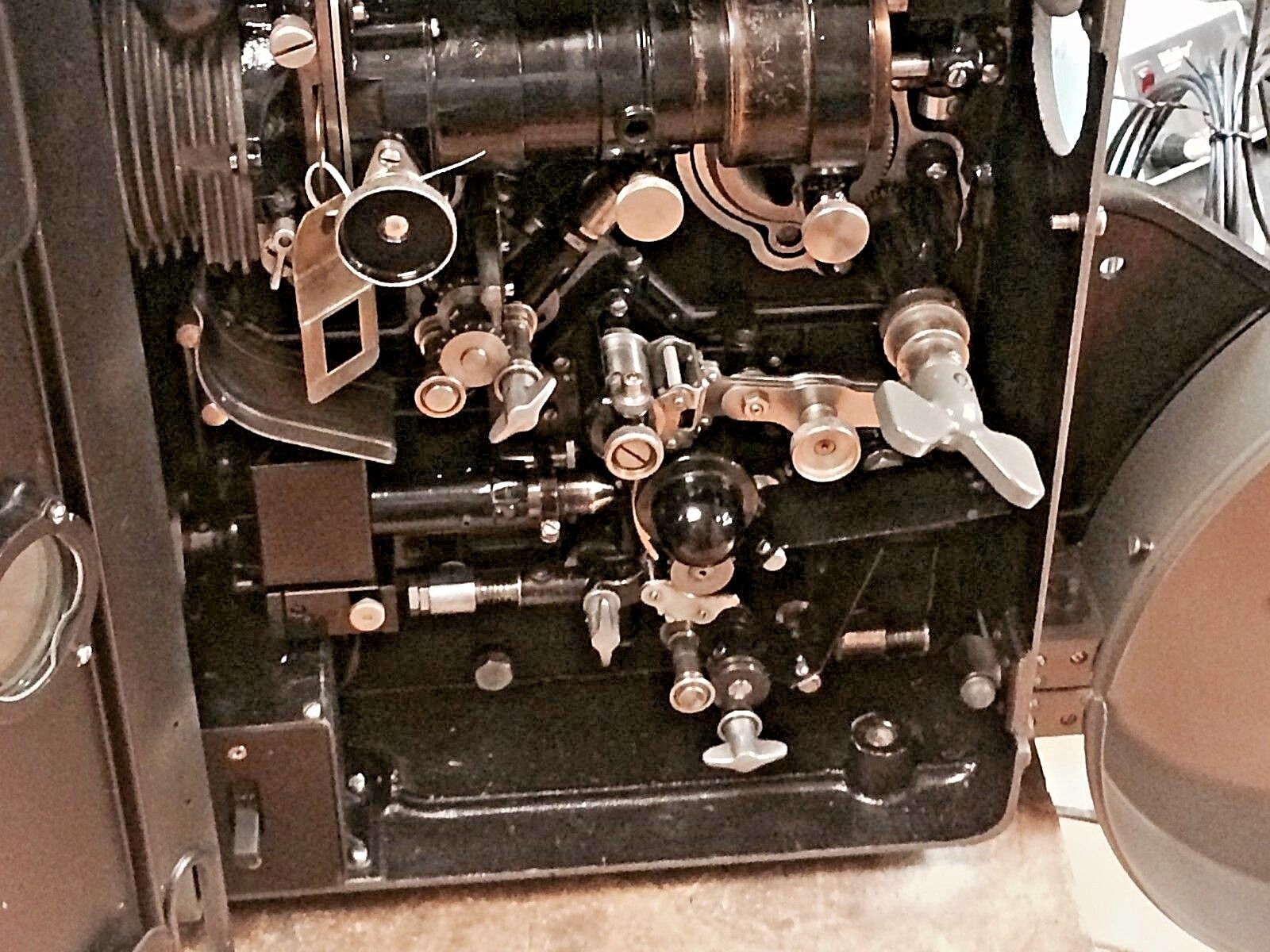

By “real collecting” Rohauer means the

acquiring of movies printed on nitrate film

stock. Nitrate, a gunpowder base, was

used for flexible film stock until the end of

the 1940s when it was superceded by

acetate (“safety”) stock. Nitrate prints,

besides being highly combustible, also

decomposed rapidly.

Rohauer can trace his interest in

collecting films back to when he was about

14 years old. That was in the early 1940s.

Although born in Buffalo, he later moved

with his family to Los Angeles, a location

that would encourage anyone’s budding

interest in film. It must have been fertile

ground for a film collector; Hollywood has

always been notoriously lazy about

preserving its filmed past and thirty years

ago there were undoubtedly more old

films lying around than there are now.

“You search out, you find out who had

films and what they were” is Rohauer’s

self-described technique. He would find

films in attics or garages. “It’s a matter of

research. It’s a very tedious and

unrewarding work because you’re not

doing it for commercial reasons. You’re

just doing it because you want to do it.”

While a student at Los Angeles City

College, Rohauer headed a film society

and in 1947 persuaded D.W. Griffith to

appear at a screening of The Birth of a

Nation. It was one of the director’s last

public appearances (he died the next year)

and Rohauer recalls that the reluctant

Griffith showed up only through

Rohauer’s persistence.

In 1950 Rohauer took over the Coronet

Theater in Los Angeles. Previously a

home for unsuccessful stage productions,

he turned it into a movie theater and,

more particularly, a showcase for his own

taste in old films. “I didn’t want to run a

commercial theater. The whole purpose

was to run classic films.”

The Coronet gradually acquired an

audience and its eventual success led

Rohauer to manage two other theaters in

Los Angeles. Among the people who

worked for him at this time was a young

usher named Stan Brakhage who wrote in

1969 that the Coronet was “the best

theater for regular presentation of filmic

works of art ever created yet in this

country.”

Rohauer cont’d.

The lack of availability of old films from

commercial distributors at that time

reinforced Rohauer in his quest for film.

In 1962, when his theaters’ leases expired,

he realized that film sleuthing was a

A few years later, in 1965, Rohauer

became the film curator at Huntington

Hartford’s year-old Gallery of Modern Art

in New York City. He was contacted for

the job by the Gallery’s director, Carl

Weinhardt, who had heard of Rohauer’s

activities in film. Rohauer, always his own

man, accepted on the condition that there

be no interference, from Hartford or

anyone else. He then proceeded to create

a film department with a populist slant, at

least partly so as not to mimic the activities

of the Gallery’s neighbor, the well-established

Museum of Modern Art.

“It was not my interest to duplicate

anything or to approximate what the

Museum had done,” Rohauer recalls. “But

in doing research about the Museum of

Modern Art I realized there was so much

that wasn’t done. They were not fulfilling

the needs of the people because they have

a very snobbish attitude about what they

consider to be good, what they consider

should be shown to the public.”

As an example, Rohauer cites one of the

first programs he did at the Gallery,

honoring comedy producer Hal Roach. “I

first contacted Richard Griffith [then

MOMA’s film curator] because the Hal

Roach thing came up too early when I first

got to the Gallery and I wasn’t ready for it

technically. So I offered it to the Museum

of Modern Art. Richard Griffith sent me a

telegram: ‘No, we’re not interested in Hal

Roach. Period. Signed, Richard Griffith.’”

Rohauer’s aesthetic vindication came five

years later when the Modern finally did

honor Roach.

Similarly, the Gallery of Modern Art

held a Ginger Rogers retrospective (“one

of the most successful programs I ever

did,” says Rohauer) after the idea had

been rejected twice by the Museum of

Modern Art. But Rohauer’s biggest

triumph while at the Gallery undoubtedly

was with someone else the Modern

wouldn’t touch : Busby Berkeley.

“That started in the early part of ’65.

When I first talked to Busby Berkeley I

said I wanted to do a tribute to him in

New York. He said, “Well, you’re nuts!

Nobody knows about me. I’m forgotten. A

tribute about what?’”

Rohauer persisted, the same way he

kept after D.W. Griffith nearly 20 years

earlier. Besides wanting Berkeley to make

a public appearance he also went after

Ruby Keeler, at that time, like Berkeley,

totally retired. Keeler was evenmore

reticent about acknowledging her

cinematic past than Busby but finally

agreed to appear in Berkeley would.

Berkeley reciproctated Keeler’s

agreement and they were both flown to

New York for the show, which opened in

November, 1965.

“We had people lined up around the

block trying to get in,” Rohauer says. The

program itself was made up of Berkeley’s

dance sequences from the Warner

Brothers musicals of 1933–37. After it

finished playing New York, Rohauer took

the films, plus Berkeley and Keeler, on a

month-long tour of London, Paris,

Switzerland and Germany. There was

unanimous acclaim for the films, and

Berkeley and Keeler, at first astonished

by the reception, realized that there was

still an audience for their work.

“It was really one of the most

exhilarating experiences I’ve ever had but

it was also one of the most difficult things

I ever did,” admits Rohauer. “The

problem with Busby Berkeley and Ruby

Keeler was temperament, particularly

Berkeley who would feel he had to pit

himself against me every day and a

number of times a day. He would always

try to do the Big Director and he would

act as I was his employee. He treated

Ruby Keeler the same way. She was used

to it. She worked for him for years but I

was not used to it.”

Rohauer’s solution was simply to avoid

Berkeley, meeting him only for the show.

The day they were returning to New York

Berkeley called on Rohauer, apologizing

for his behavior and explaining that a

week before he came to New York he had

had an operation for a possibly cancerous

growth. Not wanting to jeopardize the

tour, Berkeley had kept the operation a

secret but during the tour was suffering

from after-effects.

“He wanted me to understand, now that

it didn’t make any difference, why he was

so difficult," Rohauer explains. “‘But, you

know, Ray,’ he said, ‘I will always be

grateful to you for what you’ve done.’”

[PHOTO: Rohauer, Wm. Wellman, Ruby Keeler and Busby Berkeley at Gallery of Modern Art (1965).]

Rohauer resigned from the Gallery of

Modern Art at the end of 1967. He had

been preparing a father-son program of

works by Max (“Betty Boop” and Richard

Fleischer when Huntington Hartford

either suggested (acording to Hartford)

or demanded (according to Rohauer) that

Richard Fleischer give Hartford’s wife a

screen test. A large portion of the show,

the first tribute to Max Fleischer ever

held, was cancelled. Rohauer left, feeling

that his independence had been compromised.

He is amused today when he

recalls that Hartford was “bowled over”

by the resignation.

In 1969 Fairleigh Dickinson University

bought the Gallery of Modern Art,

christened it the New York Cultural

Center and asked Raymond Rohauer to

come back, promising complete autonomy.

He accepted (the film department had lain

dormant since his resignation) only to

meet more interference: not from Dr.

Peter Sammartino, the Center’s director,

but from Sammartino’s wife.

“She wanted to see what the programs

were in advance, what the program notes

were; if there was anything a little sexy or

out of the way or different, it had to be

dropped. I refused to do it,” Rohauer

resigned again in 1970.

By then, however, he was ready with

his biggest indpendent film program

to date: the films of Buster Keaton.

[This is the first of a 2 part article on

Raymond Rohauer. Ed. Note]

MARBLE/ Page 3 [Sept-Oct 1975]

Presenting Raymond Rohauer... Part Two

By Scott Isler

Rohauer’s relationship with Keaton

dated back to 1954

when Keaton, aware of

Rohauer’s reputation through the Coronet

Theater, approached him and told him of a

collection of films Keaton had stored in his

garage. Rohauer went and found THE

THREE AGES, THE NAVIGATOR,

SHERLOCK JR., GO WEST, STEAMBOAT

BILL, JR., COLLEGE, some two-reel

shorts... all original nitrate prints

and all in various stages of decomposition.

Rohauer had the films transferred to

safety stock before any more damage

could be done and then went about untangling

the problem of commercial

exhibition rights so the films could be

shown again.

At the same time as he was

straightening out the legal difficulties

Rohauer was also looking for Keaton films

that Keaton himself didn’t have. Some

two-reelers were found in eastern Europe

with titles in Czech, Russian and Polish. In

all, Rohauer amassed 21 Keaton shorts

(more have since been found) and all 10

features made by Keaton’s own

production company. After clearing the

rights Rohauer showed some of the films

in London but the first full presentation of

the Keaton legacy took place in the fall of

1970 at New York’s Elgin Cinema.

“The Keaton thing to me was the most

rewarding, personally, of anything I’ve

ever done,” says Rohauer, and the explosion

of interest in Keaton which the

reissues sparked certainly confirms his

claim that “I consider this my most important

work.”

Since 1970 Rohauer has continued

accumulating film and the rights to

exhibit them. He is a businessman, of

course, but one who uses his pragmatic

knowledge to further aesthetic ends.

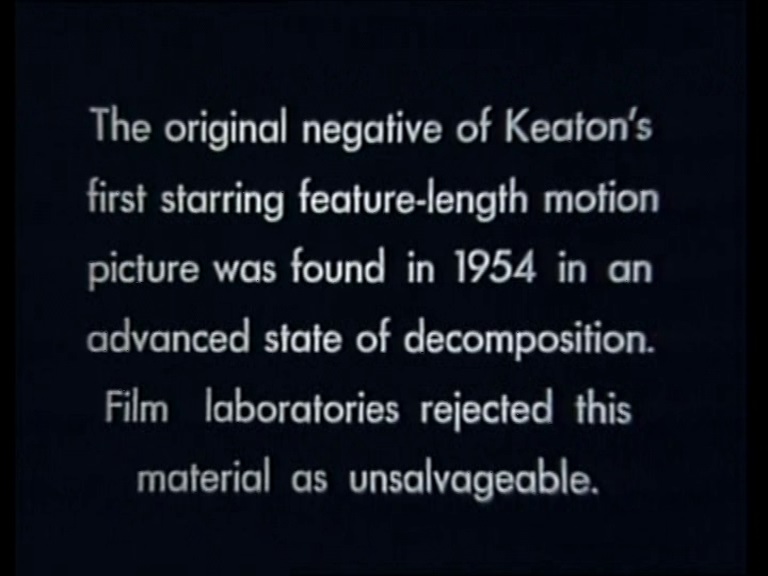

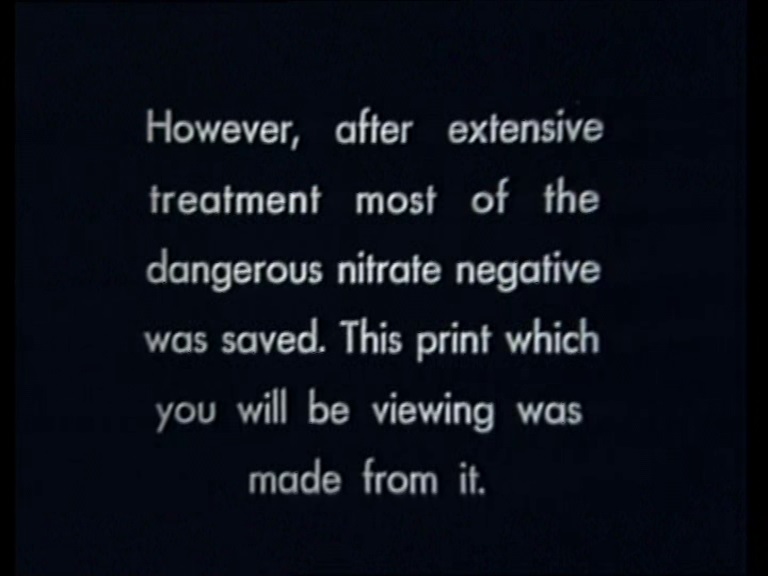

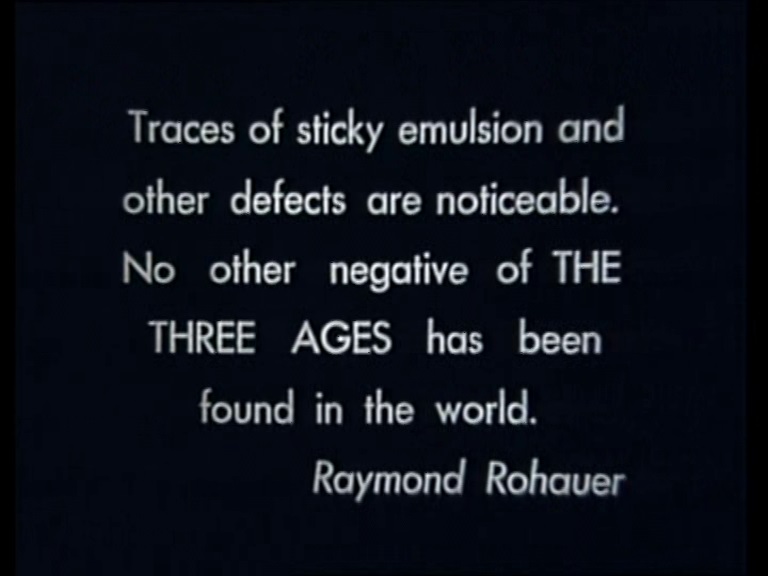

THE THREE AGES, for example, was

the first Keaton film Rohauer had

restored and the most seriously damaged

by deterioration of all Keaton’s garage

films. Rohauer explains “I used

psychological means” to get a film lab to

reprint it.

“I had Buster Keaton himself personally

deliver the nitrate original to the

superintendent of the lab. This man was

so impressed meeting Buster Keaton that

he took them. Then I went in afterwards

to place the order. So they went ahead

and they started making a dupe negative

with the emulsion running on the film.

The emulsion was coming off the film

during most of the printing so they

claimed it destroyed a $15,000 printer.

They stopped doing business with me

after that. I felt that all I cared was

getting a negative made and there were

many more laboratories to deal with. I

would ruin 10 to 20 more printers in

laboratories if it meant saving the films.”

Rohauer has a film-lover’s reverence for

celluloid. In THE THREE AGES there

was never any thought about cutting out

damaged portions. “I go to great lengths

to see that every piece is printed. Even if

[a film] is rejected by one lab I will keep

going from place to place even to other

cities, to get it done.”

Hunting for films is mainly a matter of

research (Rohauer has no staff or office)

although there is more than a bit of luck

involved. The original camera negative of

Alla Nazimova’s 1922 production of

SALOME was found by Rohauer in the

wine cellar of Nazimova’s hotel in

Hollywood.

[PHOTO: Rohauer and Keaton at Venice Airport (9/1/65).]

There have been more fortuitious incidents.

“I met a newspaperman from

Holland at the Berlin Film Festival. He

said he had 16mm. prints of some Harry

Langdon shorts. I asked what were the

titles and he said he could only remember

one of them called something like THE

LITTLE DUTCH GIRL. Langdon never

made a picture with that title. He sent me

the print. It was in poor shape, the titles

throughout were in Dutch and we couldn’t

identify it for some time. So I had to go

through the synopses of Langdon’s 25

two-reelers for Sennett to locate the

story-line that would fit this particular

short and we did find it. It was a film

called THE SEA SQUAWK made in 1925

and this is the only copy in the world that

I’ve ever found of THE SEA SQUAWK.

“I never really consider any film lost.

I’ve seen lists that are published by the

American Film Institute and the Museum

of Modern Art that claim that such and

such a film is lost. Now I may even have

copies of these films that they consider

lost. Just several weeks ago the AFI made

an announcement that there were six

Frank Capra films lost forever. Well,

that’s not true because one of them, THE

POWER OF THE PRESS, I happen to

have the 35 mm original material on. Now

the Institute knows this and they tried to

get it from me and I wouldn’t give it to

them. They didn’t say ‘Well, we did locate

POWER OF THE PRESS and Raymond

Rohauer has it.’ They just say it’s lost.”

It is in the area of commercial rights

that Rohauer has made the most enemies.

“I went into it in a depth that no one else

ever went into. I didn’t just do it on a

superficial level; I tried to understand the

copyright law. Many attorneys today still

don’t understand what it’s all about. Even

Congress is trying to rewrite the

copyright law to this day to cover modern

technology.

“Film is just like furniture or any other

property; it has an owner. Copyright is

the intangible right but film itself, the

physical thing, is tangible. The intangible

right, if you are the copyright owner,

gives you the exclusive right to make

copies, to distribute them and release

them. The property right is the physical

aspect but that’s not the copyright.”

A film copyright is good for 28 years

after which it may be renewed for another

28. Many film companies let their

copyrights lapse on old films, others went

out of business. Tracking down owners of

copyrights and clearing films for public

release can be second in difficulty only to

finding copies of the films themselves.

Once he acquires rights to a property

Rohauer isn’t lax to assert himself. For

broadcasting Buster Keaton’s THE

GENERAL in December 1965, he

brought action against New York’s

Channel 13 (WNET) and five lawsuits

against the Museum of Modern Art, from

whom the station had obtained its print.

Demanding that MOMA surrender its

prints of the film to him, Rohauer settled

for an agreement by which the Museum

would stick to the restrictions imposed by

film donors (i.e., no commercial uses).

Channel 13 agreed not to show THE

GENERAL again without Rohauer’s consent.

Although his activities may parallel

those of film archivists, Rohauer is

definitely in it for the money, a distinction

that gains him the wrath of archivists.

Rohauer views it as jealousy, the fact that

he got there before they did. The most

recent and vicious example of

Despite such unpleasantries Rohauer

seems the sort of person who always

maintains a cool exterior. It is the calm of

someone who knows what he’s doing, does

it well and is completely self-reliant.

Above all Rohauer treasures his

autonomy. “I like to be free, not to be tied

down to any office. It’s my nature not to

be pinned down. No one’s ever been able

to do that — Huntington Hartford, or no

matter who it is. The independence I will

never give up.”

Independence and a passion for film:

His own collection numbers well into the

thousands and Rohauer, afraid of fire,

catastrophe or even war, makes copies

and stores them in different countries.

Not all of these films, of course, are of

artistic or commercial interest.

“I certainly have to be dedicated to

what I’m doing to save films that have no

value as yet, maybe won’t have value for

many years to come; but that’s not important.

The thing is it must be done

now.”

Perhaps some future generation, less

concerned with Rohauer’s financial interests,

will look more kindly on his

single-minded attitude to film preservation.

“With me it’s all film. The only thing

that really draws me to anything is

film... I wouldn’t do anything else.”

[Another page of “Raymond Rohauer Presents...” was authored by Andrew Markowsky,

who pulled details from a press release about the Rohauer program at the Elgin.]

|

|

Not everything in the above interview is true.

Some of the information is fractional and some is tendentious.

We also need to be wary of the omissions.

When did Ray begin collecting Buster’s movies?

The implication is that the quest began in

1954,

when Buster and Ray first met.

I am now convinced that

1954

was indeed the year they first met, likely in the summer.

An examination of the flyers would pin this down with certainty, but I am unable to locate those flyers.

Jim Curtis makes a powerful case that they first met in

1958,

but as overwhelming and seemingly irrefutable as his evidence is, he’s wrong.

Further, Ray had already shown at least four Buster shorts at the Coronet several years before he met Buster,

but whether he had those films in his personal collection or whether he just rented them from distributors, I do not know.

|

|

It is interesting how Ray maintained that his film collection began

by inquiring about leftovers in attics or garages.

Perhaps he did that, but when you read Kevin Brownlow’s The Search for Charlie Chaplin

you discover that Ray was sniffing about in more than attics or garages.

He had contacts at warehouses and at exchanges and at silver-reclamation labs.

Ahhhhhhhhhh.

When a film was scheduled to be tossed out or chemically dissolved,

these contacts would work out behind-the-scenes arrangements to deliver these films to Ray instead.

Now, think back, back to

the interview with John Hampton of the Movie: Old Time Movies

in Los Ángeles.

John told of how he began his youthful hobby of collecting disused nitrate films

by purchasing them for a dollar a reel from the local exchanges

and also by dumpster diving at those exchanges.

Ray surely engaged in that identical activity, in Buffalo as well as in Los Ángeles,

and he expanded that enterprise beyond mere dumpster diving.

|

|

Ray was not alone in his quest.

There was another detective sniffing about for Buster’s films,

and this is where things get really complicated.

|

Rudi Blesh |

|

Olga Egorova sent me some fascinating materials,

materials that change so much of the narrative I had pieced together.

In earlier drafts of this website, I had postulated that it was Robert Smith and Sidney Sheldon

who had most likely begun the hunt to locate and recover Buster’s silent movies.

My idea seemed to fit the known evidence, but I was entirely wrong.

It was actually Rudi Blesh who had begun that hunt.

Robert and Sidney were the beneficiaries of Rudi’s efforts.

|

|

Olga’s clipping files proved that my memory is too malleable.

I read Rudi Blesh’s Keaton in 1975,

having checked it out from the just-opened

downtown Albuquerque Library,

the smelliest library on earth, but the book was not complete.

A previous patron had clipped out some photographs, and so the text on the reverse was missing.

Nonetheless, I devoured the book.

I have not read it in its entirety since that time,

but I do have it in my collection (three copies, really), and I rather frequently page through it again.

|

|

As I learned at the 1999 Busterfest in Muskegon, Rudi’s book was originally much longer.

What went to press was an abridgment.

That seemed obvious to me.

The years 1895 through 1928 fill 307 pages, but then 1929 to 1966 are a mere 63 pages.

That left me craving more information about those 36+ years.

That is why I concluded that the publisher decided largely to omit the second half of Buster’s life.

|

|

Wrong!

|

|

Oliver Scott interviewed Eleanor for his privately printed book,

Buster Keaton, the Little Iron Man,

and I read but then completely forgot Eleanor’s words.

And my goodness, did she ever have words!

Among the things she said, page 317:

“...But the last ten years of Buster’s life he put in two chapters

tacked on the end, after Buster died. He said that he was only interested in silent

film, and when silent pictures went out, he quit worrying about it, the end of the book.”

|

|

Now that we have a bit of context, we can explore.

Rudi had seen Buster’s silents and talkies in the 1920’s and 1930’s when they were new.

In his Preface, dated 1966, he wrote,

“It was a dozen or so years ago that I began seeing the Keaton films

again, at the Museum of Modern Art. It proved far more than an

indulgence in mere nostalgia. It was, in fact, a startling experience.

Cops,

The Boat,

The General,

Our Hospitality,

The Navigator — and

all the rest — were a revelation.”

It was then that Rudi decided to meet Buster in person and write his biography.

For this past half century, I had taken Rudi at his word.

I had no reason to quarrel with his assertion that he began watching Buster’s movies at MoMA

a dozen years prior to 1966, or, if we employ the simplest arithmetic, in

1954.

Even so, there is a problem, and you can probably spot it.

In 1954,

MoMA had 35mm lavenders and 16mm prints of

Sherlock Jr.,

The Navigator, and

The General.

In addition, it had one 35mm nitrate print each of

Our Hospitality and

Go West.

MoMA may or may not have had a copy of Cops but it most certainly did not have The Boat.

There was, though, a 16mm copy of Cops that was making the rounds.

Who distributed it, I do not know.

In

September 1953, the Sioux Falls Community Playhouse announced an upcoming screening of Cops on 28 March 1954.

The Goat was also available in 16mm from some distributor somewhere.

It was almost certainly pirated.

It was shown at the Eaglet in Sacramento in

February 1954.

What other Buster silents may have been floating about, heaven only knows.

There was certainly not much.

|

|

If you are like most people, you are now fed up with me for taking issue with such a small matter.

Whether Rudi saw those movies at MoMA in 1954 or 1964 or sometime in between hardly matters.

What matters is that he saw those movies at MoMA, and so why am I obsessing on this trivia?

I’ll tell you why.

You see, that tiny bit of trivia contains a telltale clue,

a telltale clue that unlocks a massive mystery.

What’s more, Rudi did not start watching Buster’s movies at MoMA in

1954,

but in

1952.

It was at MoMA that Rudi started the process of rewatching the movies,

but he nowhere says that he continued rewatching the movies at MoMA.

(Pay attention to that seemingly innocuous employment of unspecific language

that makes us think we read something that we did not actually read.

Rudi will use that device again in an interview, as we shall see.)

He continued his viewings elsewhere.

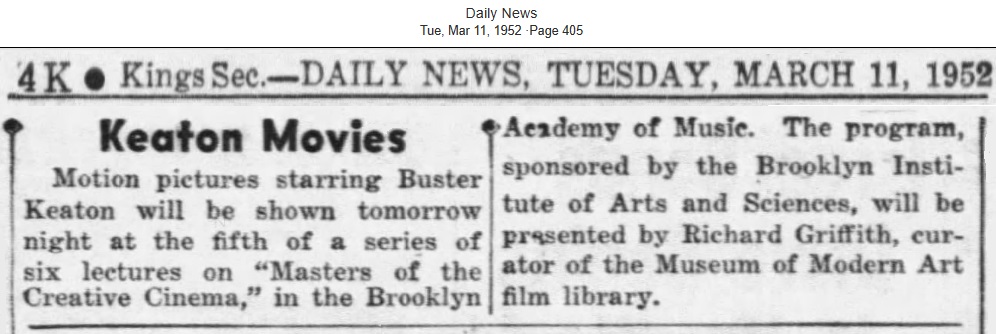

There was only a single night of MoMA/Buster screenings, as far as I can determine,

and that single night was not even at MoMA.

Shall we?

|

|

That evening at the Brooklyn Academy of Music (BAM) surely was not a five-hour marathon of five of Buster’s features.

It was probably only two of those features.

|

|

Now, I would wager that Rudi eventually arranged with a curator (Richard Griffith?) to view the other films.

Three features were available in 16mm, and the two nitrates he probably viewed on a flatbed editor.

|

|

On the page before Rudi’s Preface appear the Acknowledgments, which I read in 1975 and never

|

|

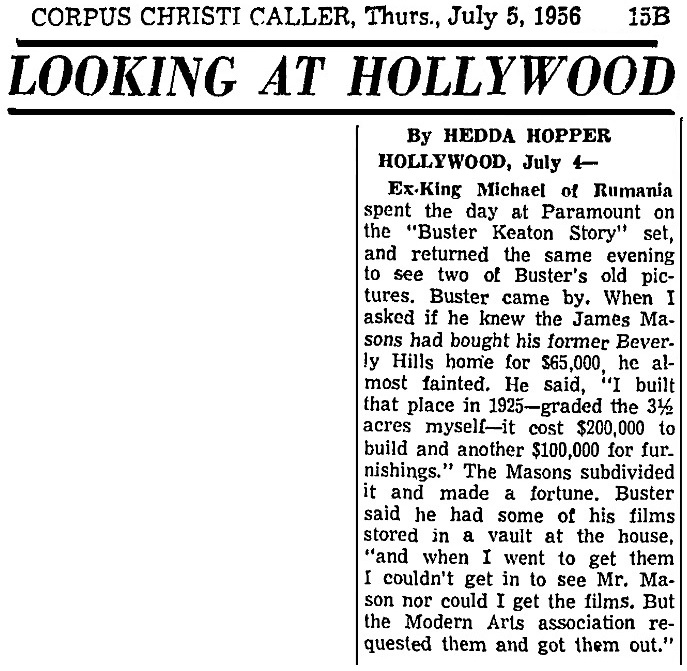

James Mason’s story can wait a little while, though.

Let’s get back to the beginning of Rudi’s adventure,

which we learn about in Kevin Brownlow’s Alla ricerca di Buster Keaton, pages 25–26.

Rudi leaves us with the impression that it was immediately after watching a few Buster movies

on that evening of Wednesday, 12 March 1952,

that he sought Buster and learned that he was headed for New York.

We need dates on this story.

Jim Curtis provides them (pp. 566–567).

The process was not immediate after all.

In fact, it was not until a year and a half after that screening that Rudi met Buster.

Buster and Eleanor returned from three months of variety revues touring

Italy

(July through September 1953).

They sailed from Le Havre aboard the

RMS Mauretania

(Rudi later misremembered this as the Queen Mary).

Rudi sent Buster a

radiogram:

“WOULD LIKE TO WRITE YOUR BIOGRAPHY.

IF INTERESTED CALL ME WHEN YOU REACH NEW YORK.”

(Oh how much I would love to learn what Rudi and his publisher offered to pay Buster for the privilege.)

Buster and Eleanor disembarked in New York City on Monday,

5 October 1953.

They took a room at the Hotel St. Moritz

on Central Park South, and Buster indeed called Rudi.

The following day, Buster and Rudi met in Central Park.

That was on Tuesday, 6 October 1953, as Jim Curtis confirms (p. 566).

Buster was agreeable to a biography,

but only on condition that his life story be told truthfully, without any whitewashing.

“I was on the crest of a wave — and then I blew it.

I don’t want any retouching.”

|

|

We have a variant version of the above episode.

Carl Hultberg privately published Rudi (and me): The Rudi Blesh Story (told by his grandson)

(Ragtime Press, PO Box 913, Orleans MA 02653, 6 November 2013, $18.99).

His memories were imperfect and his resources were lacking.

He did the best he could with imperfect memories and fragmentary documentation.

Page 67:

|

|

Buster Keaton had been a popular silent movie comedy star in the

1920s when Rudi was young. Whatever happened to the guy?

Had anyone ever written a book? As it had been with the Ragtime

story it was Hansi [Harriet Janis, Rudi’s wife] who had asked the original question. The

instigator. Rudi investigated and found that nothing of real

importance had been written regarding this compact extremely

graceful doleful yet indomitable character. Determined to contact

Keaton right away (1954) Rudi got in touch with the outfit whose

job is to know the location of every star at any given time,

Celebrities Incorporated. Where was Buster Keaton and what was

he doing? The answer: Buster was on the steamship Normandy

sailing to England on his way to France, where he still appeared

as a headliner at the time. Not wanting to waste another minute

Rudi immediately wired Buster by short wave radio, Ship to

Shore. “Would he consent to allow Rudi to write biography” Rudi

said that Buster was so impressed that someone would go to all

the trouble to reach him on board ship that he agreed on the spot.

|

|

See? I told you it was a variant.

Rudi wrote in his Preface that he decided to write about Buster

immediately upon seeing some of Buster’s silents at MoMA in 1954.

Yet, as far as I can determine, there were no MoMA screenings of Buster’s silents in 1954.

There were screenings, courtesy of MoMA, at BAM in 1952.

Carl tells us that the idea for the book was not Rudi’s at all, but his wife Hansi’s,

and he implies that Hansi got that idea in 1954.

Makes sense.

Rudi saw some Buster movies in 1952 at BAM and spoke about them often enough

that Hansi bellowed forth with, “Well, why don’t you write a book?”

That is when Rudi checked to see if there was already a book and discovered that there wasn’t.

Celebrities Incorporated informed Rudi that Buster was in the middle of the ocean

but could be reached by a Ship to Shore radiogram.

|

|

Rudi told Kevin that he contacted the ship when Buster was returning to NYC at the beginning of October 1953.

Carl wrote that Rudi contacted the ship when Buster was leaving for France by way of England in January 1954.

Rudi remembered that the ship was the Queen Mary, but the passenger manifest on

Ancestry.com reveals that the ship was the RMS Mauretania.

Carl says that the ship was the Normandy [sic; actually Normandie] during its voyage to England in 1954.

Ancestry.com records a ship manifest for the S.S. Ile de France

departing NYC on 30 December 1953 and bound for Le Havre,

indicating that Buster and Eleanor planned to stay abroad for three months.

That was a later trip, though, for the Cirque Médrano and for British television.

Do you begin to understand why I never accept any account of anything as accurate?

This is why I

|

|

Rudi spent several weeks, over the course of two years or more, October 1953 through probably June 1956,

at Buster’s house at 1043 South Victoria Avenue in Los Ángeles,

interviewing him on reel-to-reel tapes.

Buster was quite open and expansive, with a memory that was surprisingly detailed and accurate.

Unlike many interview subjects, Buster was a true raconteur and he explained stories fully,

invariably utilizing the classical

|

|

We need to jump ahead two decades.

|

|

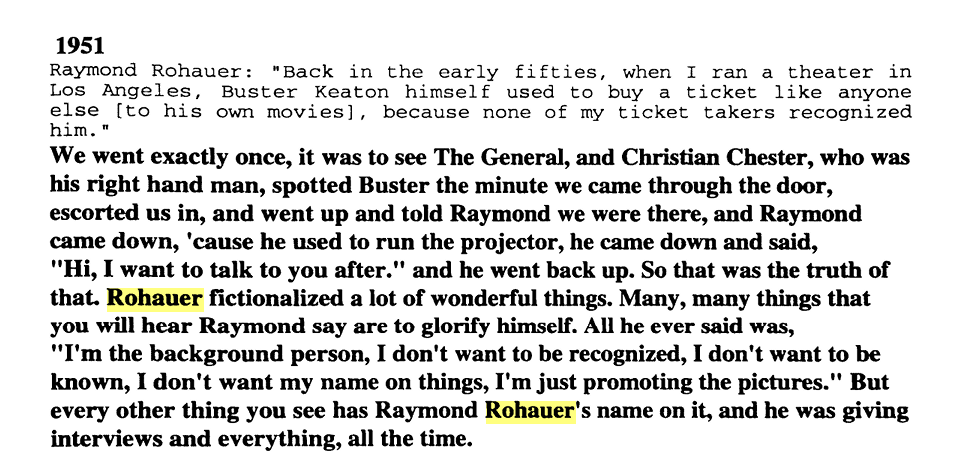

On 18 December 1972, Raymond Rohauer interviewed Marion Mack on stage for a screening of The General.

That took place at the

Ontario Film Theatre, housed in the Ontario Science Centre,

770 Don Mills Road, Toronto.

The interview appeared in print in Richard Joseph Anobile’s photonovel,

and one of the comments that Ray made on stage was,

“Back in the early fifties, when I ran a theater in Los Ángeles,

Buster Keaton himself used to buy a ticket like anyone else, because none of my ticket takers recognized him.”

With that quote, we can segue into the best book about Buster ever printed.

|

|

The best book about Buster, the best book of all, is an unofficial, unlicensed volume

|

|

|

Eleanor was in the Coronet exactly once.

She did not realize that Buster later returned on his own.

That in itself tells us something.

Buster attended likely because Ray invited him.

Eleanor didn’t bother because she had precisely zero interest in such things.

So Buster went on his own.

Whether he told Eleanor where he was going remains a question to which we shall never know the answer.

When he got back home, though, we can be pretty sure that he never mentioned his little outing.

Actually, I would hazard a guess that he returned with some frequency to watch his own movies,

whether Ray showed them privately or publicly.

|

|

I had been under the misapprehension that the Coronet was a private members-only club.

As such, it would not have had or needed a ticket booth.

Well, to my surprise, yes, there was a ticket booth at the Coronet.

|

|

Many nights, but not all nights, the Coronet operated strictly as a private club and admittance was only for members.

On other nights, the doors were open to anybody who wanted to see a show.

Stage plays were probably all open to the public.

Some but not all films were for members only.

My guess, which is only a guess, is that underground films

that had not been made under the MPPDA jurisdiction were necessarily shown only to members,

but that more commercial films with MPPDA seals (or equivalent) were made available to anybody.

Educational films, documentaries, university films, and films made for classroom or medical use

were probably exempt from such standards and were probably open to the general public.

After a few months of operation, the Coronet no longer announced its films in the newspapers.

Instead, the Coronet mailed schedules to members.

So, now let us ponder that one particular show that Buster and Eleanor attended in the summer of 1954.

If the Coronet did not advertise, then how on earth did Buster and Eleanor know to show up to buy tickets?

|

|

Olga Egorova, once again, came to the rescue and supplied this gem from an unpublished interview in

Marion Meade Buster Keaton Research Files at the University of Iowa:.

|

|

Marion Meade: Right. Let me get... Let me start at the beginning with Ray.

When you first met him, what was your impression of him? He was quite young then.

|

|

|

Eleanor Keaton: Oh, yeah. He was very young.

|

|

|

Marion Meade: He was a young.

|

|

|

Eleanor Keaton: He was just a avid film fan, is all you could say.

He was running, managing the Coronet Theater on La Cienega.

|

|

|

Marion Meade: Is that the one... I thought... Like a studio. Right.

|

|

|

Eleanor Keaton: In the front. Yeah. Lovely theater inside, 750 seats, I think.

|

272 seats. |

|

Marion Meade: Is it still a theater?

|

|

|

Eleanor Keaton: Oh, yeah. They do real shows in there now.

Anyway, we saw an ad in the paper that they were going to be doing The General.

Buster says, “Let’s go see it

in a real theater.”

In fact, I don’t think

I’d ever seen it.

“Let’s go to the movies.”

So we went to the Coronet and paid our two dollars.

Christian Chester, the old man, his “adopted father,” Raymond’s —

|

It was not advertised in the paper. Note the wording! Eleanor almost certainly had seen it already, but in a clubhouse, not “in a real theater.” Kristian Chester. |

|

Marion Meade: I didn’t know who he was. I didn’t know —

|

|

|

Eleanor Keaton: Raymond’s parents were killed when he’s not too old,

and Chris practically raised him, I guess. Of course, he was a friend of the family.

|

Ray was born out of wedlock on 17 March 1924.

His mother was Rose Mary Fiebelkorn,

5 July 1893 in Buffalo through 18 May 1952 in Los Ángeles.

She bestowed the father’s surname upon Raymond, though in his teens he was known as Raymond Fiebelkorn.

(For whatever it might be worth, his |

|

Marion Meade: I see.

|

|

|

Eleanor Keaton: And then I found out later, after Raymond died,

he had a |

Ray had three |

|

Marion Meade: So you went and you saw —

|

|

|

Eleanor Keaton: We went... Chris saw us and recognized Buster, of course.

So we went on.

At the end of the movie... Because Raymond was running a projector up above,

and at the end of the movie, he’s up there like this and started talking and this and that.

And Buster said, “Well, I got a bunch of films in the garage. You can have them if you want them.

They’re only going to sit there and spoil.”

Of course, he came to the house, and that started it.

|

|

|

Marion Meade: You were living in Cheviot Hills?

|

Buster lived at

3151 Queensbury Drive in the Cheviot Hills neighborhood of Los Ángeles

from 1932 or 1933 through sometime around 1944,

when he moved in with his family at

1043 South Victoria Avenue.

|

|

Eleanor Keaton: No, Myra’s house on Victoria.

|

Buster and Eleanor left the house on Victoria in

June 1956.

Yet Curtis has Buster and Ray first meeting more than two years later, in about September 1958.

Clearly something doesn’t add up!

|

|

Marion Meade: Right.

|

|

|

Eleanor Keaton: That started that.

Then he went from our original six or eight films, whatever it was we had, it started...

Then he found...

James Mason called Buster and said, “I’ve just got into the...”

It was a secret storeroom with a...

You had to hit the wall in a certain spot to open it,

and they found it after they’d been looking there a long time.

He found all kinds of film in there, including some of Buster’s.

He said, “You want them? I’m going to get rid of them.

I want them out of there, because they’re old nitrate.

They could explode.”

So Buster, at that time, called... I think Rudi Blesh was out working on the book at that time,

and the two of them went up and retrieved all the films and brought them back

and viewed them and gave them to Raymond to be cleaned up and transferred to safety stock and whatever.

That gave Raymond a few more.

By then, he has about 10 or 12 all together, and then he went collecting from there.

|

Eleanor paid next to no attention to this development,

which is why her memory was so poor.

It becomes clear that the Buster she cared about was the Buster of 1954, not the Buster of 1924.

At the time, she was not particularly interested in the older films

and she certainly did not have the personality of an investigator.

The search for the old films, their discovery and recovery,

was just a little bit of commotion in the background, nothing that concerned her.

|

|

Eleanor Keaton: The last thing he found, Kevin Brown and David put together, was Hard Luck.

The first time anybody saw that, including me or anybody else,

was at Palladium in London where I was there three years ago.

I guess it’s been three years.

I went over to do radio and TV and all that stuff for the Hard Act to Follow before it was on the air.

They had a big [to-]do at Palladium. It was so exciting.

They had Miles Davis, who was tremendous composer, musician, conductor.

He wrote a whole original score for |

Brownlow, not Brown. Carl Davis, not Miles. knew, of course, WHAT it was. |

|

Eleanor Keaton: On the other short...

I don’t remember what it was.

Could have been Cops or something.

But they had this young man, and he was a |

|

|

Marion Meade: Sounds wonderful. First of all, Raymond... The transfer —

|

|

|

Eleanor Keaton: Raymond was almost dead. He came that night. He had been —

|

|

|

Marion Meade: He really looked that —

|

|

|

Eleanor Keaton: I never saw him. He was hiding.

He came over from Paris to the Mayfair Hotel, and Kevin... David knew he was there.

He talked to David on the phone, because he wanted to see Hard Luck.

He’d never seen it put together.

He wanted to see his due.

At the last minute, just exactly on time as the lights were going down, David and Linda,

who did the research for Hard Luck, they saw him.

He sneaked in, and he had...

The Palladium does not have air conditioning.

It was quite warm in that theater.

He sneaked in with a heavy overcoat on, and sat in the back row and watched Hard Luck.

In the middle of the other short, they went and... David and Linda went and spoke to him.

In the middle of the second short, he got up and left,

because he didn’t want anybody to see.

He was down to about 95 pounds. [crosstalk 00:08:28].

|

|

|

Marion Meade: Well, it was his AIDS.

|

|

|

Eleanor Keaton: I’m sure it was AIDS. Nothing was ever said, but I’m positive.

|

|

|

Marion Meade: Probably. If he was wearing an overcoat in the summer, it sounds like AIDS, doesn’t it?

|

|

|

Eleanor Keaton: I’m positive it was AIDS. And he was down to 95 pounds.

He only lasted maybe two months after that.

He made it home to New York and tripped to his bed, and I don’t think he ever got up.

Nothing was ever said about what he died of, but I’m positive. I know it was AIDS.

|

|

|

Marion Meade: No, it wasn’t. Alan Twyman or Richard... I forget his —

|

Richard Gordon. |

|

Eleanor Keaton: I told Alan, I said, “I know it was AIDS.”

|

|

|

Marion Meade: He said, “Well, he wasn’t expecting to die.

That’s why his apartment is such a mess, because he didn’t make any preparations.”

But some people —

|

|

|

Eleanor Keaton: He may not have thought he was going to die, but everybody else did.

Who’s Richard? I didn’t know any of those —

|

|

|

Marion Meade: He’s a... He handles the foreign rights for Keaton Films.

He’s Alan Twyman’s... He distributes —

|

|

|

Eleanor Keaton: The counterpart.

|

|

|

Marion Meade: Yeah. Right. I forget his last name.

|

|

|

Eleanor Keaton: The only person... I get all my money through Alan.

|

|

|

Marion Meade: Right.

|

|

|

It is obvious that Eleanor never learned the details and got the story muddled.

She also misremembered things, which was rather uncharacteristic.

Once again, though, there is invaluable information here,

along with puzzles that suggest their own solutions.

|

|

Eleanor said that she and Buster saw an ad in the paper.

“We saw an ad in the paper....

Buster says, ‘Let’s go see it in a real theater.’ In fact, I don’t think I’d ever seen it.

‘Let’s go to the movies.’ So we went to the Coronet and paid our two dollars.”

I don’t think they saw an ad in the paper,

because I don’t think there was any ad in the paper,

or any announcement in any paper at all.

I’m pretty sure that Eleanor had indeed seen the film twice before.

She almost certainly saw the 40-minute 16mm abridgment at the Movie Parade in March 1941, which Buster attended.

My best guess is that the reason Buster attended was so that he could bring Eleanor along.

As we know, the Movie Parade was just an office space, not “a real theater.”

Then she almost certainly saw MoMA’s 16mm print of the full film on Tuesday, 26 April 1949,

at the Westwood Community Clubhouse, which had invited Buster to be the guest of honor.

A Community Clubhouse, of course, is not “a real theater.”

The Coronet was indeed “a real theater,” albeit a small and rather plain one,

and it was scheduled to show MoMA’s 16mm print of the

|

|

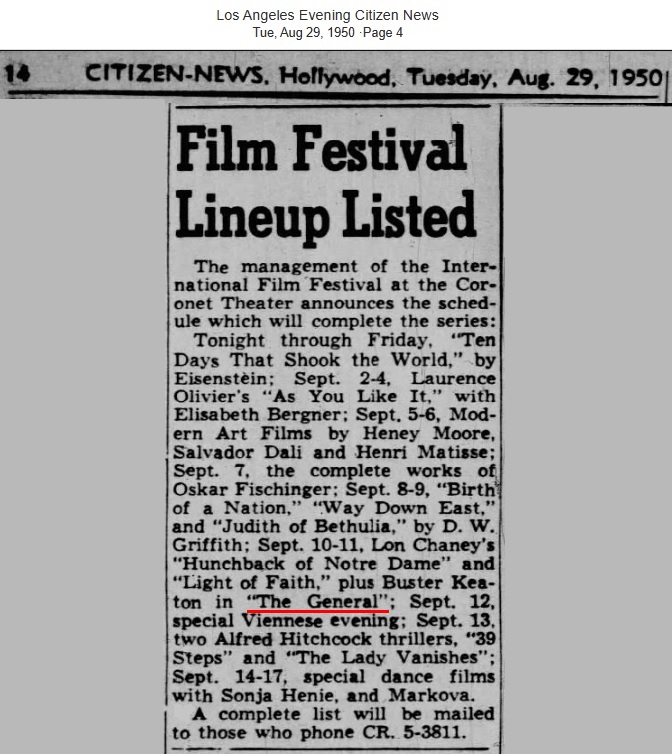

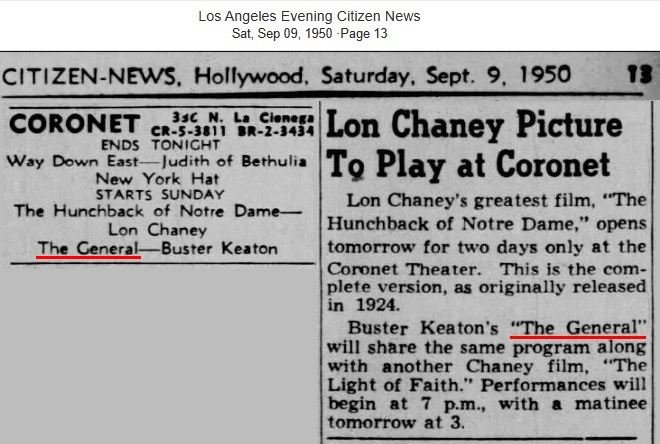

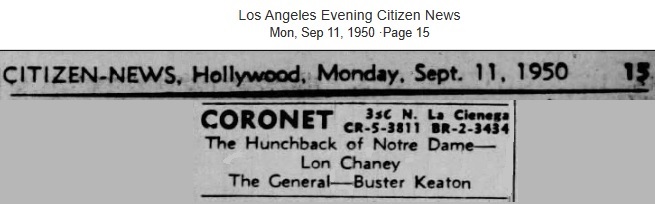

As for any showings at the Coronet, the only ads and press releases for The General that I have been able to locate are these,

but they are from several years earlier:

|

|

Note that these ads and press releases are all from 1950, a few years before Ray Rohauer claimed he first met Buster.

Did Buster and Eleanor attend one of these shows in 1950?

I don’t think so.

(Had they attended the November booking, they would probably have mentioned something about the four short films.)

As you can see, the Coronet announced FIVE Keaton films, including The General.

What were the other four?

The other four were undoubtedly short subjects, but which ones?

Buster’s silent shorts were not available at this time from any distributor,

with three possible exceptions I can think of: The Goat and Cops and The Balloonatic.

The Goat and Cops, as we learned above, seemed to have been available in 16mm from some distributor(s?) somewhere somehow.

Tobis-Klang-Film reissued The Balloonatic, left side lopped off, in Germany in

1935, with a music track by Armand Bernard.

This was also issued in France under the title Malec Aeronaute

and in England, wrongly retitled Balloonatics.

There is also some indication that a French 16mm edition of The Haunted House was also floating around, though I have no details.

Could Ray have included any talkie shorts from Educational Pictures or Columbia Pictures?

Who knows?

Remember, Ray had contacts at silver-reclamation centers and at film exchanges and so forth,

and he was always on the lookout for discarded films.

He would pay the asking price to rescue them from destruction (which was totally against the rules)

and he would then license or purchase the rights, if there were any rights.

By 1950, several of Buster’s silent shorts had fallen into the public domain in the US,

in addition to Cops and The Balloonatic, namely,

The Butcher Boy,

Coney Island,

Out West,

Good Night Nurse,

One Week,

The Play House,

The Blacksmith,

The Boat,

The Paleface,

My Wife’s Relations,

The Frozen North, and

Day Dreams.

My best guess is that the fourth of the four shorts shown at the Coronet was one of the above,

maybe Coney Island, which had somehow survived the mass destruction of Roscoe’s movies.

Whatever the short films really were,

we can see that Ray had indeed gathered some of Buster’s movies prior to meeting Buster,

or, at the very least, he knew where he could borrow or rent them.

|

|

Now, think back to Scott Isler’s interview with Ray in MARBLE, quoted above.

Ray said something fascinating, something he would repeat endlessly to the end of his days:

|

|

Rohauer’s relationship with Keaton

dated back to 1954

when Keaton, aware of

Rohauer’s reputation through the Coronet

Theater, approached him and told him of a

collection of films Keaton had stored in his

garage. Rohauer went and found THE

THREE AGES, THE NAVIGATOR,

SHERLOCK JR., GO WEST, STEAMBOAT

BILL, JR., COLLEGE, some two-reel

shorts... all original nitrate prints

and all in various stages of decomposition.

|

|

How would Buster have known of Ray’s reputation?

Ray was the 16mm film programmer at the Coronet.

How on earth would Buster have known that Ray was the guy to rescue rotted 30-year-old nitrates?

That never made sense to me.

Well, let’s think some more about this story.

|

|

When Eleanor talked with Oliver Scott, she said nothing about Buster offering Ray any films.

When Eleanor talked with Marion Meade, she did indeed say something about Buster offering Ray some films that would otherwise just spoil.

Another interview, though, proceeded differently.

|

|

If you ask a question 20 different ways you’ll get 20 different answers.

Don McGregor asked Eleanor the same question that Oliver Scott and Marion Meade asked her,

but he asked it in a different way and he got a different answer.

Here is what we read in McGregor’s little pamphlet about Buster: The Early Years

(Eclipse Enterprises [81 Delaware Street, Staten Island, NY, 10304], 1982).

Let us turn to pages 24 and 26:

|

|

McGregor: During the 1940s when you

were married, he never showed any of the

films. At that point you had never seen

any of his films?

Eleanor Keaton: Before we were married

he arranged to show Battling Butler so I

could see it. That was the first one I saw

and then gradually over a period of time I

saw others....

McGregor: What made Buster first go

down and meet Ray and tell him about the

films in the garage?

Eleanor Keaton: Ray had the Coronet

Theater in L.A. at the time, and we heard

about it, and that he was going to be showing

The General. So we went running

to

see The General. In those days Ray was

up in the projection booth running the

films. Somebody went up and told him we

were there. After the film was over he

came down and met us and we talked to

him a little bit. And we told him about the

films we had.

McGregor: Buster had never shown these

films he had in the garage?

Eleanor Keaton: No.

|

|

So there you go.

Buster had arranged a screening of Battling Butler.

Surely that was a vault print that was projected for them in an MGM screening room in Culver City.

Buster could arrange it since both he and Eleanor were employees at the time.

We do not detect Eleanor’s enthusiasm to see his other films.

As for the films in the garage, they just corroded over time.

Buster took no care of them.

Eleanor expressed no interest in them or even the slightest curiosity.

|

|

The show at the Coronet that Buster and Eleanor attended was not advertised, as far as I can tell,

and yet Eleanor said to Marion Meade that “we saw an ad in the paper.”

To Don McGregor she explained that “we heard about it.”

What I think happened is that someone that she and Buster knew

showed them the Coronet flyer that announced a showing of The General.

Decades later, Eleanor remembered that she and Buster had “heard about it.”

She thought about it again and misremembered the ad in the flyer as an ad in a newspaper.

It is now time to put on your thinking caps and ponder the mystery:

Which one of their acquaintances would have told them about the screening and shown them the flyer?

|

|

Well, which one of their acquaintances was in the Los Ángeles area at the time?

Which one of their acquaintances knew that Buster had a few rotting, unprojectable nitrate prints in his garage?

Which one of their acquaintances was studying the history of silent cinema?

Which one of their acquaintances was writing about Buster’s silent movies?

Which one of their acquaintances would have sought out screenings of silent films, especially Buster’s films?

Which one of their acquaintances would have introduced himself to Ray Rohauer?

|

|

We can conclude that Rudi Blesh was sniffing all over Southern California for Buster’s movies.

Indeed, there is evidence for this in his book, Keaton (NY: Macmillan, 16 May 1966, $8.95;

London: Secker & Warburg, June 1967, 55s), p. 302:

|

|

In 1953, when a friend of Buster Keaton asked to see it projected,

he was told a surprising thing. “The present print is worn out,” an

executive said. “It”s been our training picture. Ever since 1928 we’ve

made each new comedian study it. From Durante to Abbott and

Costello, from Mickey Rooney to Red Skelton and the Marx

Brothers.”

The MGM man spoke with evident pride. But it is equally evident

that he was not thinking of Buster Keaton, a man whom MGM had

already long since forgotten. He was thinking, MGM story, MGM

direction, MGM production.

|

|

Okay now, who was this friend who approached an MGM executive in 1953 for a screening of The Cameraman?

By now, you can figure out quite easily that this friend was none other than Rudi himself!

And if Rudi was searching for The Cameraman,

he was searching for all the other Buster silents as well, beyond any doubt.

|

|

Rudi’s sniffing would certainly have led him to the Hamptons’

Movie: Old Time Movies at 611 North Fairfax Avenue in Los Ángeles.

His sniffing might have led him to the

Nickelodeon

|

|

Carl Hultberg mentions nothing about any films in Buster’s garage.

Yet, on pages 68–69, he tells us something else:

|

|

As he

was gathering material for the biography Rudi was approached

by the Keatons and offered the position of managing Keaton perhaps

as a

|

|

Why would Buster and Eleanor need a manager?

Buster already had an agent, Ben Pearson.

His contracts were commercial, not

|

|

No, said Rudi, he couldn’t accept, but wasn’t there a young man

involved with silent movies locally, working with the Harold Lloyd

estate perhaps? A fateful comment as it would turn out. Sure enough

this person, associated with the art house Coronet Theatre

in Los Angeles was eager to work with the Keatons.

|

|

No, Harold Lloyd wanted nothing, absolutely nothing, to do with Ray Rohauer

or with any of the other proprietors of 16mm silent venues.

Nonetheless, despite that gaffe, this story is beginning to make sense, maybe, possibly, kinda, sorta.

My tentative hypothesis, which Olga or somebody else will probably tear to shreds,

is that, upon arriving in Los Ángeles, Rudi began to ask around to see Buster’s silents,

the ones he had so enjoyed in the 1920’s.

To his dismay, the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences had none.

MGM seems to have given him the

|

|

Since Ray was shortly scheduled to show MoMA’s 16mm print of The General,

it must have been Rudi who showed Buster and Eleanor the flyer and suggested that they attend.

He must have told Buster and Eleanor to talk with Ray about the films in the garage.

Ray just might be able to do something about them.

This MUST have occurred just hours (or less!) before curtain time.

Note Eleanor’s phrasing:

“...we heard... that he was going to be showing The General.

So we went running

to see The General....”

No need to go running unless they were in a rush to arrive before curtain time.

I bet Rudi attended with Buster and Eleanor that night.

That is why Buster brought up the topic of the films in the garage.

Buster had lost interest in the films, but he knew that Rudi needed to see them,

and he knew that Rudi could not see them unless somebody with the

|

|

Another possibility, or, rather, probability:

Why did Ray book the MoMA print of The General in the summer of 1954?

Because he had been chatting with Rudi for several months,

and the two agreed that it would be a good idea for the Coronet to show the movie yet once again.

Rudi was pretty sure he could convince Buster to attend,

and that prospect certainly caught Ray’s imagination.

It probably took Ray half a year to schedule a booking of the print.

This paragraph is all guesswork, nothing more.

But think about it.

Yes, this could have all been a coincidence,

but why would it have been a coincidence when all the elements were in place to make a plan?

Rudi probably mentioned that Ray booked the movie because Rudi wanted to see it with Buster,

and so he got Buster to agree to keep this evening free so that they could attend a movie together.

An hour or two before curtain, Rudi reminded Buster and Eleanor about the show, and they all went running over to see it.

If this was all planned, then the only reason Eleanor agreed to go running to the Coronet was just to be polite.

|

|

Let us examine another fragment from Don McGregor’s little pamphlet,

Buster: The Early Years.

The cover announces it as “The Authorized BUSTER KEATON FILM FESTIVAL ALBUM

with scene by scene frame

|

|

The only

|

|

Let’s now quote at length from the interview.

|

|

Rohauer: ...By

1954,

when I met Buster, I had a pretty

big reputation for running those kinds of

films. Keaton came into the Coronet with

his wife and asked to see me. I was in

the projection booth when he came in and

they called me from the booth and said

Buster Keaton was there to see me. I said

“C’mon, you’re pulling my leg.” They said,

“Well, he says he’s Buster Keaton.” I went

down and sure enough, Keaton was standing

there with his wife. He said, “I understand

you save a lot of old junk. I’ve got a lot of

stuff in my garage, if you want to take a look

at it.” I said, “I’d be glad to,” and we met the

next day at his house. He was living on Victoria

Avenue in Los Ángeles at the time with

his mother, in the same house which he

bought for her when he was a top star. He

gave it to her as a gift and she had lived there

ever since. In 1954 Buster moved in with her

in that same house. Buster’s entire family was

living there, too; he always supported all of his

relatives.

So we struck up a deal. I said, “Look, if I

save these films, if I transfer them to safety

stock and this and that, do we have a deal?”

He said, “Sure, but I don’t own them.” So I

had to start working on the legal rights. This

continued for a number of years following

that — establishing the legal rights to these

films. And then pursuing, getting copies of all

the films which he didn’t have.

McGregor: Did he have a lot of the films the first day you went there?

Rohauer: A number of them, not a lot.

Three Ages,

College,

Sherlock Jr.,

Navigator.

McGregor: When you first walked in there,

you didn’t have any idea of what you were

seeing. They were just reels of old films. Nobody had ever seen...

Rohauer: No, nobody had seen these films.

They were in nitrate form, you couldn’t show

them anyway.

McGregor: The first film you saved was The Three Ages.

It was in such a combustable

state at the time you discovered it...

Rohauer: In going through all the films, I

noticed that The Three Ages was in the worst

shape. Every reel had hypo — that is where

the emulsion starts to erode due to a chemical

reaction on the film. It’s highly dangerous

when it gets to that stage. The film either

turns into jelly or it could be explosive if not

properly stored because nitrate has a

McGregor: So even though Buster had

these films, he didn’t show them.

Rohauer: No, he just had them. They were

remnants of the past.

McGregor: He never showed them to Mrs.

Keaton?

Rohauer: No. But the bulk of the (restoration

of his) films came from the worldwide

pursuit that followed that.

McGregor: Back to The Three Ages...

Rohauer: Well, I said to Keaton, “We’ve got

to do this one immediately. This won’t last.”

he said, “Okay, if you want to waste your

money on it,” because he never believed for

one minute that these would be worth anything.

Or that there was an audience for it.

So we put the cans of film in Keaton’s trunk

and he drove the car and we went over together

to the General Film Laboratory in

Hollywood.

[NOTE: General Film Laboratories Corporation,

1546 Argyle Avenue, Hollywood 28, tel.

McGregor: What did Buster say when this

was going on?

Rohauer: Nothing. He never spoke

much... at any time. I’m not talking about

when we were alone, but when there were

strange people around he never got into the

conversation.

So, they went through the film and

cleaned it up and tried to get it through the

printer. They gave me a room and Buster

went home. For several days I worked on the

film, cutting out maybe a couple of frames

here and there.

McGregor: The film was all stuck together?

Rohauer: Yes, it had to be peeled apart.

And it had to be respliced wherever there

were splices so that it wouldn’t come apart in

the printer. Finally they put the film through

the printer.

McGregor: Did you have any idea when

you were going through the film what was

going to be in there?

Rohauer: No. I hadn’t seen the picture yet.

When the entire process was done, the lab

said I had ruined their printer. The emulsion

had come off the film and they were going to

charge me $15,000 extra for the printer.

They dropped that because all they had to

do was change the plates in which the film

was running through in the printer, which

they finally did. But now I couldn’t do any

more lab work there. They didn’t want to

touch the other Keaton prints. So I had to

find other places.

McGregor: Once you had the film restored,

did you immediately run it?

Rohauer: No, because making the print

from the new negative didn’t come until

later. It was a matter of just saving the film, all

the films. You must understand that there

was no commercial attitude there. No compelling

reason to make a print and look at it

right away. The other films had to be saved.

Keaton kept saying, “You’re throwing your

money away.” But it didn’t make any difference

what he said. I had to do it. It’s a

compulsion.

|

|

Eleanor claimed that Ray asked to speak to Buster.

Ray claimed that Buster asked to speak to Ray.

No lab in 1954 would, on principal, have refused to work with nitrate,

which was still circulating everywhere.

After the Three Ages job, Ray continued to use General Film Laboratories Corporation

for his preservation and printing needs, as we shall see.

So Ray’s story about being barred from General Film Laboratories is nonsense.

|

|

I’m wondering again.