Timeline — Trying to Trace the Provenance of the Surviving Elements |

|

For half a century, I was wondering about the provenance of The General and Buster’s other silent movies.

Now, thanks to the research I needed to perform to write this essay,

I am finally beginning to get a sense of things.

Buster’s movies were seen only when they were new.

Once they had finished their series of first-, second-, and third-run bookings,

nobody was expecting to see them ever again,

and nobody cared to see them again.

The films vanished from movie screens and most seemed to have vanished altogether, discarded as worthless junk.

Much of the below chronology is probably wrong,

and if you can offer corrections, I’m all ears.

|

| 1926–1927 | The General is in wide distribution. |

| March 1927 | The Harvard University Film Foundation acquires two 35mm positives from United Artists. Presumably, at least one of these positives is a lavender. |

| 1928–1929 | The General is in subrun distribution, though it still has a few major première dates in 1928. |

| 1929 | UA issues an abridged 16mm edition to schools and nonprofits. |

| 1930–1931? | The General is still in subrun, but rarely, and it is also shown on special occasions.

Various cinemas continue to book it as a revival.

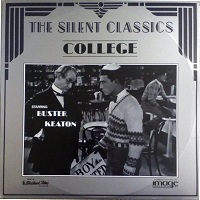

Unexpectedly, College and Steamboat Bill, Jr., are still making the rounds well into 1931 and perhaps beyond that.

(The General is still in |

| 1933? | The 16mm abridgment is bootlegged and issued under a different title, Roaring Rails. This is for use in schools and film societies. Does that sound familiar? An early exhibition is on Thursday, 16 March 1933, by the Roosevelt School PTA in Fair Lawn, NJ. By about 1945, Charlie Mogull’s company, Mogull’s Camera & Film Exchange, Inc., 68 W 48th St. (later 112 W 48th St.), NYC, was the distributor. On Archive.org, we see two of Charlie’s catalogues, and neither is dated. Both were scanned from the collection of Karl Thiede, and I assume it was Thiede who determined that the earlier catalogue, the one with the orange cover, is from 1940, and that the later one, the one with the grey cover, is from 1945. The 1940 edition does not include Roaring Rails, but the 1945 edition does. So, we can assume that Charlie Mogull acquired the item from a previous distributor, but who that previous distributor was remains a mystery. Charlie Mogull still had this item for rent as recently as the 1980’s. |

| 1935 | The Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) asks the Harvard University Film Foundation if it would consider donating its collection of 13 films, which included The General. |

| 1936 | Harvard agrees and donates its collection to MoMA. |

| 1941 | The Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) circulates at least one 16mm print of The General to libraries and schools and nonprofits. The 16mm circulating print was soon enough hammered and was missing significant material. (I presume MoMA ran off a replacement print. Well, I hope MoMA ran off a replacement print.) |

| 1947? | MGM options remake rights to The General

and orders a |

| Jan 1953 | In the first days of 1953, the British Film Institute acquires a 35mm fine-grain duplicating positive of The General. The BFI immediately makes a 16mm print, which it quickly screens at the recently opened National Film Theatre. Who makes this donation, nobody now knows. My best guess is that the fine grain is a gift from United Artists. After all, who else could possibly have donated such an item? It quickly becomes either the #1 or the #2 biggest movie hit in London. |

| Sep(?) 1955 | James Mason discovers that Buster’s personal prints, including the preview print of The General shown at the Alex in Glendale, are abandoned on his property. He allows Buster use of them to make copy negs, but before Buster can finish, Mason donates the materials to AMPAS. |

| Jan 1956 | James Mason donates the remainder of the films, including the preview print of The General, to the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences. A few other materials are dug up here and there at about that same time. |

| Jun(?) 1954 | Rohauer presents The General in 16mm, surely the MoMA print, at his Coronet in LÁ. |

| ca. March 1956 | The General, likely a 16mm dupe of the preview print, is screened at USC. Buster takes questions from the audience. |

| Apr(?) 1957 | Paul Killiam acquires a copy neg of The General,

derived either from UA’s camera neg or from MGM’s |

| 29 Jan 1958 | The CBC broadcasts Killiam’s 50-minute “Hour of Silents” edition of The General. It bears a 1957 copyright. |

| 02 Aug 1958 | The BBC broadcasts Killiam’s 50-minute “Hour of Silents” edition of The General |

| 1959 | Killiam assigns William C. Dalzell to reduce the “Hour of Silents” edition to 25 minutes for inclusion in a 16mm series, “The History of the Motion Picture,” for release to public schools. The narration is spoken by Frank Gallop. |

| Jan 1960 | Rohauer orders a 35mm dupe neg of the Academy’s print of The General, which, of course, had once been Buster’s personal print. This is the preview print that had been shown at the Alex in November 1926. |

| 19 Jun 1960 | Rohauer sues the Berkeley Cinema Guild for showing The General. Pauline Kael, the manager, responds that The General is public-domain and easily available from a half-dozen distributors (which distributors? if this was true, then those distributors had just duped MoMA’s copy, I’m certain). Rohauer withdraws his charge. |

| 11 Aug 1960 | Killiam has the commercial US première of his 25-minute “History of the Motion Picture” version of The General included as an episode of “Silents Please” on ABC. |

| circa 1960? | MoMA removes the Keaton titles from its circulating catalogue. Was this in response to threats of legal action? |

| Sep 1961 | The British Film Institute (BFI)

issues The General for film societies in 35mm, 16mm, 9.5mm, and 8mm,

and it proves to be one of the more popular titles in the catalogue.

The source is unknown, though we know it was not the BFI’s January 1953 archive print,

which was never duplicated.

(If I had to guess,

I would guess that United Artists, after surrendering copyright,

donated a lavender to the BFI specifically to make prints available to film societies and schools.

Whether it was UA Hollywood that donated a US copy negative, or UA London that donated an export copy negative,

I don’t know. |

| 1961 | Buster licenses European rights to KirchMedia and oversees Konrad Elfers’s new orchestra score for The General, but KirchMedia rejects the score and insists upon jazz replacements with lots of sound effects. |

| Feb 1962 | KirchMedia acquires the rights from multiple claimants and licenses the film to Atlas, which exhibits The General and Cops throughout West Germany. Distributors in Croatia, Denmark, France, Belgium, Spain, Finland, Sweden (probably), Japan, Czechoslovakia, Hungary, Poland, Romania, the UK, the USSR, and Portugal also license the rights from KirchMedia. The KirchMedia edition is cropped from Rohauer’s 1960 dupe neg of the Nov. 1926 preview print. Buster was mistaken when he said that this was a composite derived from several release prints. The KirchMedia edition includes the revised soundtrack by Konrad Elfers. |

| 1961? | A distributor offers public-domain copies of The General to collectors. Despite endless hours, days, nights, weeks, months of searching, I could learn nothing more about this. Then, on the evening of Tuesday, 28 March 2023, I learned part of the story. This was an 8mm edition from Phil Alcuri’s Entertainment Films Company, 850 7th Ave, Manhattan NY 10019. It was most likely a dupe of John Griggs’s dupe of the MoMA 16mm print. |

| Feb/Mar 1962 | Henri Langlois presents the world’s first Buster retrospective. This takes place at the Cinémathèque française. Some of the prints are in-house archive copies. Rohauer filled out the program by providing some 16mm prints. 16fps, no musical accompaniment, as Langlois dogmatically demanded of all silents. This retro results in a new burst of interest in Buster, with articles and books pouring forth from the French presses. |

| 04 Jun 1962 | Harvey Cort includes Killiam’s 25-minute abridgment of The General in The Great Chase. Narration by Frank Gallop. Music by Larry Adler. |

| Sep 1963 | “The Golden Age of Buster Keaton”: Rohauer presents his entire Keaton collection at the Venice Film Festival. Rohauer’s prints were all 16mm. Prints borrowed from the Eastman House, the Cinémathèque française, and the Milan Film Library were presumably all 35mm. There were presumably accompanists for them. This was the second-ever Busterfest. |

| Sep 1963 | Regal Films International issues a (single?) 35mm KirchMedia print of The General to cinemas in the UK. If there was ballyhoo, it was not evident in the newspapers currently available in the online archives. By November this was occasionally booked as the second bill to a new release. Its titles are not the English originals, but translated from the German. |

| 29 Dec 1965 | The General

is broadcast on WNET Channel 13 in NYC

as part of its series on “A Million and One Nights of Film.”

Each episode includes introductory comments,

and each film is a silent from the MoMA collection.

The series runs only from Oct 1965 through May 1966, six episodes, one of which was canceled.

Who provided the introduction

for The General remains a vexing mystery.

George Gent in The New York Times wrongly reported that the film was broadcast

dead silent, without music.

The truth was that

other records,

MoMA’s staff musician Arthur Kleiner accompanied each of these films on piano. For the record: Wed 27 Oct 1965, 8:30pm, Tol’able David, intro by Stanley Kauffmann Wed 17 Nov 1965, 8:30pm, Variety, canceled due to rights snafu Wed 29 Dec 1965, 8:30pm, The General Mon 31 Jan 1966, 8:30pm, The Phantom of the Opera Mon 28 Feb 1966, 8:30pm, Storm over Asia, intro by Willard Van Dyke Mon 28 Mar 1966, 8:30pm, Queen Kelly, intro by Gloria Swanson Sun 08 May 1966, 4:00pm, Tol’able David, intro by Stanley Kauffmann |

| 01 Oct 1966 08 Oct 1966 15 Oct 1966 22 Oct 1966 |

Rohauer presents selections from his Keaton collection at the Philadelphia Museum of Art. He presents individual Keaton films at a few other such venues over the next few years. |

| 1967 | Leopold Friedman sues MoMA for damages and demands the surrender of all its Keaton materials (Curtis, p. 688). |

| Mar 1967 | The Academy surrenders its Keaton prints, including Buster’s personal print of The General, to Leopold Friedman’s attorneys. I presume these prints eventually migrated to Rohauer’s possession. |

| Jan 1968 | Rohauer presents “The Films of Buster Keaton” in London. This program includes The General. All or most prints are 16mm. This is the first time most of these films had been seen in the UK since they were new. This Festival inspires David Robinson to write a book-length appreciation of Buster’s films. |

| 1968 | Rohauer moves “The Films of Buster Keaton” to Paris. Jacques Robert reissues several Keaton films in France from 1968 through 1970, three with scores by Claude Bolling. The General is released sometime in 1970. No further details. |

| circa May 1969 | Blackhawk licenses a large portion of the Killiam Collection for future home release. |

| 25 Sep 1969 – 29 Oct 1969 | Rohauer presents a “Buster Keaton Retrospective” at the Surf in SF. It includes Keaton’s and other comedies besides. This program includes The General. All Keaton/Rohauer prints are 16mm, though prints from other suppliers are likely 35mm. This is the first time since their original releases in the 1920’s that most of these Keaton films are seen in the US. |

| Jul 1970 | Killiam reconstitutes The General from his cans of trims, but he pieces it back together incorrectly and he does not include a goodly amount of the footage. Blackhawk issues Killiam’s three versions of The General for home use only. |

| 22 Sep 1970 – 26 Oct 1970 | Rohauer moves the Keaton portion of the Surf retro to NYC as “The Buster Keaton Festival.” All prints are full-aperture 35mm. This Festival later tours several cities in the US and Canada, and other places around the world as well. |

| Sep 1970 | Bill Scott and Skip Craig of Jay Ward Productions

purchase MGM’s |

| Apr 1971 | Rohauer acquires the remaining Buster Keaton Productions rights from Friedman. |

| 03 Aug 1971 | Killiam débuts a 16mm print of his altered feature edition of The General on television. It includes a new tinting scheme by Karl Malkames. Piano accompaniment is by Bill Perry. |

| Sep 1971? | Killiam adds the altered b&w feature edition of The General to his catalogue for commercial bookings in full-aperture 35mm. He licenses double-sprocket 16mm rights to Films, Inc. |

| Circa 1971? | Upon discovering that The General is in the public domain, multitudes of distributors duplicate older bootlegs of the MoMA print and Killiam’s 1970 print to create an infinitude of prints and videos of deplorable quality. |

| 1972 | Thunderbird offers a 16mm dupe of the Killiam edition, b&w, with a music score compiled from dance bands. (Tom Dunnahoo, Thunderbird Films, PO Box 65157, Los Ángeles CA 90065) |

| Dec 1972 | Rohauer and Marion Mack begin touring Canada, the UK, and the US with a new print of The General, optically reduced to .620"×.864". This is from Rohauer’s dupe of the Nov 1926 preview print. The organ soundtrack is by Lee Erwin. |

| Dec 1978 | Marion Mack retires from touring due to failing health. |

| 1979 |

Jay Ward gives Rohauer access to the |

| 1980?? | Charles Tarbox somehow acquires a poor dupe of MoMA’s 35mm screening print and offers it for rental and sale in 16mm through his firm, Film Classic Exchange. He may have done this as early as 1936 or as late as 1984. My best guess is about 1980. |

| 1980 | Rohauer encourages Brownlow and Gill to raise funds for a preservation copy of the Camera A OCN. |

| Sep 1987 | Rohauer allows David Gill and Kevin Brownlow

to present The General as part of their “Live Cinema”

series. The print is presumably from the duplicate negative he had made in 1960,

though it is possibly from the superior duplicate negative made by Bill Scott and Skip Craig for Jay Ward in 1970,

which in turn derived from the 1947/1948 |

| 1988? | A print of The General is made from the original camera neg, probably with funds raised by Kevin Brownlow. This new print is shipped to England where it is used for further presentations of the Brownlow/Gill/Davis “Live Cinema” series. My understanding about this is worse than vague. |

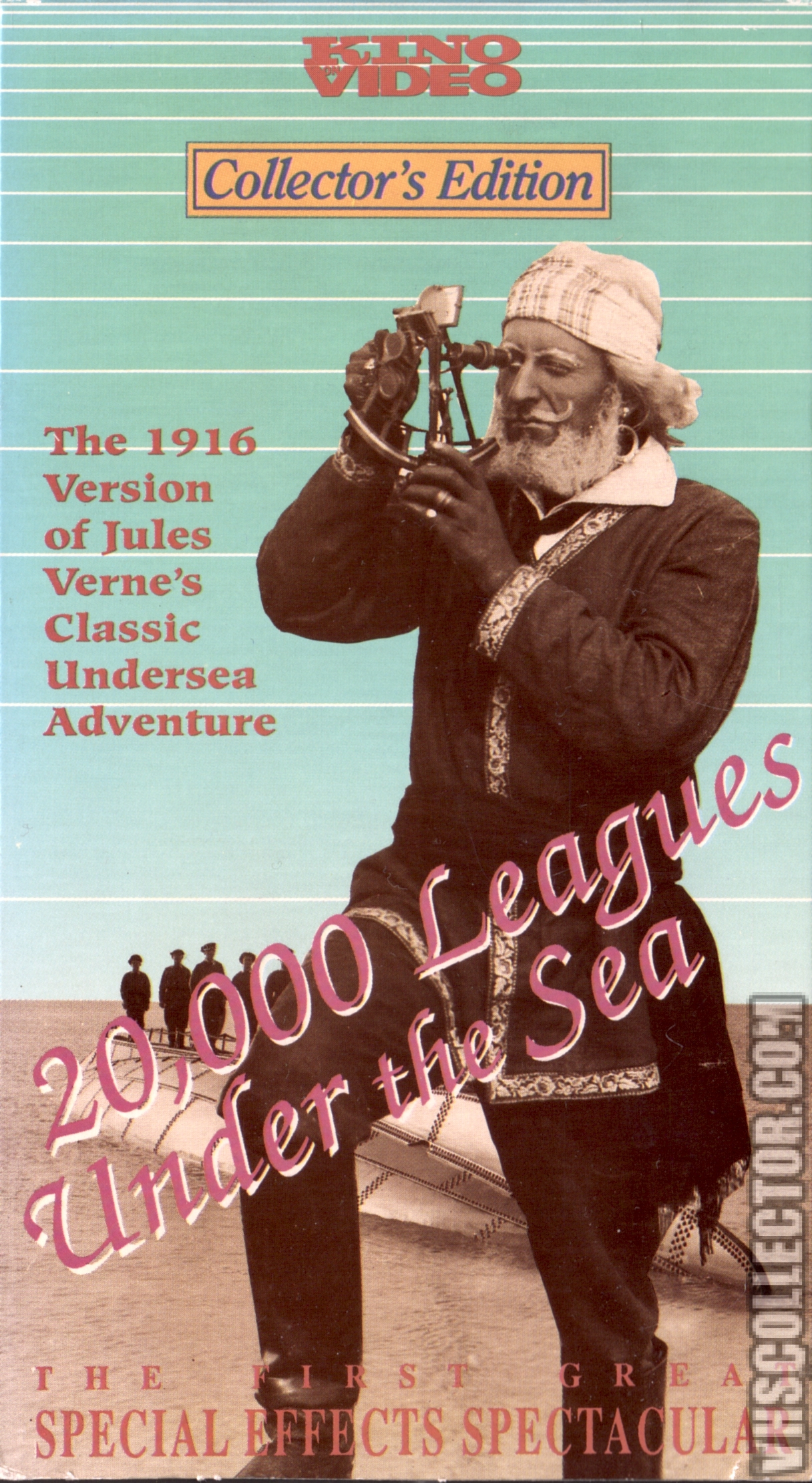

| Oct 1989 | Kino issues a

“Collector’s Edition”

VHS of The General with an

organ score by Gaylord Carter,

who, as organists are wont to do, played this straight through in one go.

His music has a 1978 copyright claim by Bob Harris’s company, RHD,

and it was recorded to a screening of a 16mm print taken from MoMA’s master material.

For the VHS, Kino went to a black-and-white 35mm print instead, complete with full opening credits.

The print is recent and obviously a copy, though a rather fine one.

It is a 2nd- or 3rd-generation copy of a master held by MoMA.

The flicker gives this away as a dupe.

How this copy came to be made, I do not know.

The eight small reels were cement spliced together onto a pair of larger reels,

and there were no cue marks anywhere.

That is not because they were painted out.

They were never there to begin with.

So this is definitely a few generations removed from the lavender, and it was never used for public screenings.

As usual, for the video transfer, the techies zoomed right in to the center of the frame

( |

| 01 Jun 1995 | “The Art of Buster Keaton” is issued on laserdisc and VHS in three phases: Vol. 1, 01 Feb 1995, Vol. 2, 05 Apr 1995, Vol. 3, 01 Jun 1995. Prior to this time, some of these films were available on wretched-looking pirated copies and other dupes. Rohauer had never permitted most of these films to be issued on home video. This is the first chance, ever, that fans have of seeing most of these films, which we had only longingly read about in books. It is Vol. 3 that contains The General. David Shepard is in charge of the entire series, and for The General he miraculously finds a tinted original. He builds a digital edition in part from this tinted original and in part from the November 1926 preview print, but he neglects to include the opening of Reel 7. Until this time, nobody had suspected that The General was tinted in its original release. For no reason I can discern, David transfers both Battling Butler and The General at 26fps, or 97½'/min. Too too too too too fast. I ask why he did that, but his response is that silent cinema lasted only about 35 years and he has spent many more years than that working with silent films and knows what he is doing. That doesn’t answer my question, but oh well. On a chat room, I just now discover, David said that the cue sheet specified 26fps. No it didn’t. The quality of the transfer is not so good, though it is much better when viewed on a computer. Where this release print was found, when this print was found, how this print was found, remain vexing mysteries. Where this print is now, I haven’t the foggiest idea. |

| 14 Feb 2013 | The LÁ Times claims that the original camera neg is now in the possession of Cohen’s Rohauer Collection. |

|

Now, let’s do a summary of the summary.

What original 1920’s elements are known still to exist?

|

|

• The preview print shown at the Alex in Glendale.

Buster abandoned this print, James Mason donated it to the Academy,

the Academy surrendered it to Leopold Friedman in 1967, and then Rohauer got it probably in 1971.

|

|

• An original release print from 1926/1927 that David Shepard miraculously found somewhere,

which he released on a Kino laserdisc box set in 1995.

How David found it, where he found it, and where it is now, I cannot even imagine.

|

|

• The domestic original camera neg.

I presume it was United Artists that donated it to USC probably in the

|

|

• A b&w original nitrate Soviet release print from 1929,

export edition (camera placement almost imperceptibly different),

on file at Gosfilmofond.

I need to get a scan of this, but, alas, politics are making things a mite difficult.

|

|

I think those four elements are it, unless some foreign archives managed to preserve some original release prints.

I don’t think anything else survives.

And all four elements seem to have survived only by accident.

Now, to be fair, when we typically find a silent film,

we find tenth-generation bootlegs, battered, censored, cropped, modified.

Some we find only in 9.5mm or only in 8mm.

We dream, I mean we DREAM, of finding the OCN, or the preview print, or an original release print in good condition.

Almost never happens.

For The General, we really lucked out.

This borders on miraculous.

Had the production company followed standard protocol, the preview print would have been destroyed once the edit was final.

Had United Artists followed standard protocol, once demand for bookings had died down,

it would have sent the OCN to be chemically dissolved for silver reclamation.

Had projectionists followed standard protocol,

they would have hammered the release prints into hopeless unusability within three weeks.

Had the exchanges followed standard protocol,

the release prints would have been returned to United Artists for destruction.

When it comes to The General, we are almost unbelievably lucky.

|

|

The irony?

The General is now one of the most easily available of all silent films, and has been since 1970.

It is difficult for us to imagine, but for nearly four decades, from 1931 through 1969,

it was almost impossible for anybody to see The General.

It was a title remembered by old-timers,

a title known to the younger generations only as a small chapter in a 1959 book called

Classics of the Silent Screen.

It was not a movie that most people could ever have hoped to see,

unless they happened to belong to a private film society that booked the MoMA print.

Then, just as Rohauer begins to show his 35mm copy at festivals,

Killiam issues an altered rival copy

at almost exactly the same time that Jay Ward Productions issues a modified “sound version,”

and then within two years Rohauer issues a version with an organ score.

To top all that off, it seems that every film pirate on earth bootlegged the MoMA edition or the Killiam edition or one of the two Rohauer editions.

|

|

OCN

(Original Camera Negative)

Almost no negative from the silent days survives.

Negatives were tossed into the ashbin about 90 years ago as being useless obsolete junk of no further commercial value.

Amazingly, the domestic camera negative of The General survives to this day.

Miracle.

So, let me take the information above and use lots of guesswork to figure out what likely happened.

• In the mid-1930’s, MoMA purchased a lavender of The General.

• In January 1953, the British Film Institute (BFI) acquired a brand-new diacetate print of The General.

Records about this donation are lost.

My best guess is that this print was a gift from United Artists, in all likelihood printed from the OCN.

Was this print from United Artists Hollywood, printed from the domestic OCN,

or was it from United Artists London, printed from the export OCN?

• If Bill Scott got his story right, and if his story was recorded correctly,

he was able to use the

• In 1990, Phil Carli mentioned to me that the OCN was then at the University of Southern California (USC).

United Artists had surrendered all legal claim to the film as of 1 January 1955, you see,

allowing it to enter into the public domain.

So, a donation in return for a tax break would have made sense.

If Phil was right, then I can only assume that United Artists donated the OCN to USC in 1955 or later.

I assume Phil was right, because he tends to be right about everything,

but he was wrong about one detail:

By probably the mid-1960’s, the OCN was no longer with USC,

but was likely with Leopold Friedman.

• Ed Watz tells a story to

Nitrateville about a meeting that must have occurred in 1987 or not long before.

This story indicates that Rohauer had somehow acquired the OCN from USC:

• By 1988 there was a new print made from this OCN.

To the best of my knowledge, that new print was used for future “Live Cinema” presentations in the UK.

It was also used as the source for the Kino

• Susan King, in “Famous

Cache of Vintage Films Headed to Homes and Screens,” The Los Ángeles Times, 14 February 2013, wrote:

Assuming that the above information is correct, not invented, not misremembered, not misreported,

and assuming that my guesses to fill in the gaps are correct,

the above is the history of the domestic OCN from 1926 through the present day.

Does the export OCN still exist? I haven’t the foggiest idea.

|

Random Remarks |

|

|

ANOTHER CURIOSITY.

An episode of The

|

|

INADVERTENT PLAGIARISM.

I hadn’t read Jim Kline’s intro to his book,

The Complete Films of Buster Keaton,

in about ten years.

When I reread it the other day (late March 2003),

I was amazed at how much I borrowed (stole?) from him,

without even realizing it.

Is that what they call cryptomnesia?

|

Buster on Video

|

| |||

|

|

|

|

|

|

NEWS:

A new print directly off of the camera negative,

probably the same print that Kevin Brownlow and David Gill and Carl Davis used for their roadshow engagements,

has been issued on DVD and

|

|

Another noteworthy edition is the restoration from Lobster Films in France.

It is mastered from a shrunken black-and-white dupe (probably from the 1970’s),

but nonetheless the quality of the image is pretty good.

There are some nice extras, too.

But, unfortunately, no Carl Davis score.

|

|

Kino in 2017 reissued The General on

|

|

|

|

Our Hospitality.

This major Keaton work was available from HBO on NTSC laserdisc (Image Entertainment, product number ID6863HB)

and on NTSC VHS (“Legendary Silents,” product number 0281).

Again, these are out of print, but can still be found on eBay.

|

|

The Early Shorts.

Ten of Keaton’s fourteen shorts with Roscoe Arbuckle were recently released on Region 1 NTSC DVD and NTSC VHS from

Kino on Video

in New York as a two-volume set called

“Arbuckle & Keaton: The Original Comique/Paramount Shorts, 1917–1920.”

A superior copy of one of these shorts (The Garage),

an eleventh short (Oh Doctor!), and an uncredited Keaton cameo

(an abridgment of The Iron Mule), are available on volume 4 of Image’s

“Slapstick Encyclopedia”

on Region 1 NTSC DVD and NTSC VHS.

A twelfth Arbuckle/Keaton short, the long-thought-lost The Cook,

is in release from

Milestone.

An impressive 4-volume Region 2 PAL DVD set is

Buster Keaton — L’Intégrale des courts métrages 1917–1923,

which contains almost all of Keaton’s surviving footage in silent shorts.

Twelve of these shorts have been remastered for an American release,

The Best Arbuckle-Keaton Collection.

The various restorations don’t match.

If you’re a true connoisseur, you’ll need to purchase all the editions.

|

|

The Deluxe Box Set.

The bulk of Keaton’s independent solo work is available on DVD, laserdisc, and VHS

from Kino in a ten- or eleven-volume set called

“The Art of Buster Keaton.”

The films are beautifully restored by David Shepard, and the latest eleven-volume NTSC DVD edition is almost perfect.

Earlier releases (1995–2000) were missing important footage in Day Dreams and Convict 13.

Even the current release is missing two shots in Sherlock Jr.

and one shot in The General.

This box set opens with the dull and overlong preview print of the Metro film, The Saphead,

a feature in which Keaton appears, but over which he had almost no control.

A slightly better copy of Sherlock Jr.

(with infinitely better music by Vince Giordano and the Nighthawks)

was until recently occasionally shown on American Movie Classics.

|

|

Some of the Kino transfers (converted to PAL) were also once released in France,

in a brutally expensive box set.

Some shorts were also included, taken from the “L’intégrale des courts métrages” set,

and The General was taken from the Lobster set:

|

|

|

|

Visual comparisons of some of the various editions are

here,

and be prepared to have your mind blown and your nerves shattered.

|

|

Beware of all other video editions of Keaton’s independent work,

many of which are incomplete, copied from pathetic dupes,

sometimes transferred at speeds that are far too slow, and have dreadful music scores.

|

|

The Cameraman. Keaton’s first MGM-produced silent,

which was also the last true Keaton film,

is finally available in a beautiful DVD edition.

More about this below.

|

|

Miscellanea. One of the rarest and most curious Keaton appearances

was in a trade-show short from 1921 called Seeing Stars,

in which he briefly appears as

Charlie Chaplin’s waiter.

Only one incomplete copy is known to survive, and no historian seems to be aware of the film’s existence,

hence its nonappearance on over-the-counter video, though a few home-made copies have been circulating on VHS.

The opening scene was included in the recent

Industrial Strength Keaton

DVD set,

which also includes another recent discovery, the six-minute Character Studies,

which stars Carter De Haven “impersonating” Roscoe Arbuckle, Buster Keaton, Harold Lloyd,

Jackie Coogan, Douglas Fairbanks, and Rudolph Valentino, courtesy, of course, of clever editing.

(There is a claim that this film was a private joke that was never shown to the public.

Rubbish. Character Studies was commercially released in 1928.

It played at the Strand in Hartford in

March 1928,

at the Highland in Los Ángeles in

May 1928,

and it played at the KiMo in Albuquerque from

7–10 March 1928.

It must have been widely released, though rarely advertised.

So, despite the ban, Roscoe Arbuckle did occasionally still appear on regular movie screens. So there.)

|

|

|

Something Resembling an Update.

After I updated this page in 2014, I stopped looking at it for a good eight years or so.

I did not realize how much had happened in those eight years or so.

Various companies have put out ever-more editions of Buster’s works on DVD and

|

|

|

|

CONFLICTS. For decades, I dreamed of helping to create the definitive book on The General,

since so many people have done so much research on the film.

The book could be accompanied by a definitive

|

Further Research |

|

Perhaps the best place to start learning about Keaton’s life and work is the web site operated by the

Damfinos — The International Buster Keaton Society.

|

|

Another superb source is the three-part video by Kevin Brownlow and David Gill called

Buster Keaton: A Hard Act to Follow,

which was available on laserdisc from Image Entertainment and on three VHS cassettes from

HBO,

but is now out of print.

Now, 35 years later, we can see that it contained serious errors, but in 1987 those errors were invisible.

We did not have sufficient research behind us to know any better.

So there was the usual mistake about how Buster got his nickname (which was not what he had been told),

the usual mistake about The General having been a

|

|

Steamboat Bill, Jr., and the Falling Wall

Okay boys and girls, cats and dogs, ponies and horses, listen up!

I am tired of tiresome stories that make me so darned tired; so, let us fix this once and for all.

Everywhere you turn, in countless documentaries, commentaries,

magazine articles, books, lectures, comments on blogs,

comments underneath YouTube clips,

the same fibs are repeated over and over and over and over ad nauseam.

Please think for a moment.

When you buy a ticket to a magic show,

you actually see the magician saw the woman in half.

He does it, right before your eyes,

and the other 3,000 people in the auditorium all see exactly the same thing, right?

Yet, even if you don’t know how the magician performed that trick,

you know that the magician didn’t really saw the woman in half.

Yes?

Well, I hope you know that.

My late lamented friend, James Randi, the Amazing,

So, you saw, with your very own eyes, that the magician sawed the woman in half.

Not only that, there are 3,000 witnesses who will verify your accusation.

Yet you and the 3,000 witnesses all know that the magician didn’t really saw the woman in half.

Yet when you watch a movie and see a

I am not a magician.

Yeah, I took a brief course from a local magic shop and I learned (and have since forgotten)

some nice magic tricks, and that is when it occurred to me that I have zero patience to do the practice,

and even less patience to do the same tricks over and over and over again for

more and more and more and more audiences.

Bores the living daylights out of me.

So I never pursued it.

Since I never pursued it, I am free to reveal any darn secrets I so choose.

I never took no oath.

Though I have forgotten how to do the tricks,

I remember the most valuable lesson, the lesson that I use every last day.

Those magic lessons taught me how to think backwards.

It is impossible to do research worthy of the term without thinking backwards.

Not just research on magic.

Research on ANY and EVERY topic.

You need to know how to think backwards, else your research will fall to pieces.

Rudi Blesh (p. 290) stated,

“And now comes what is surely the high point of Buster Keaton’s

long career of courting death for real.”

I am sorry that Blesh ever wrote such a sentence.

That single sentence has derailed research everywhere

and has, over the decades, caused others to paint a completely wrong image of Buster.

That single sentence is wrong.

I wish I had been the

Buster continued.

“The whole gang except Gabe fought me on that one. ‘You can’t

do it.’ Bruckman threatened to quit. My director, Chuck Reisner,

stayed in his tent reading Science and Health. First time I ever saw

cameramen look the other way. But Gabourie and I figured out all the

details. We knew it would work.”

Shall we now think backwards?

Below is a clip from Steamboat Bill, Jr., as seen on YouTube.

Watch it, then drag the dot back to the beginning and play it again.

When the wall is about to fall, press the PAUSE button.

Then you can advance frame by frame with the period key,

and you can go backwards frame by frame with the comma key.

Did you watch it frame by frame?

What did you see?

If you were alert, you saw all sorts of things you could never possibly notice at regular speed.

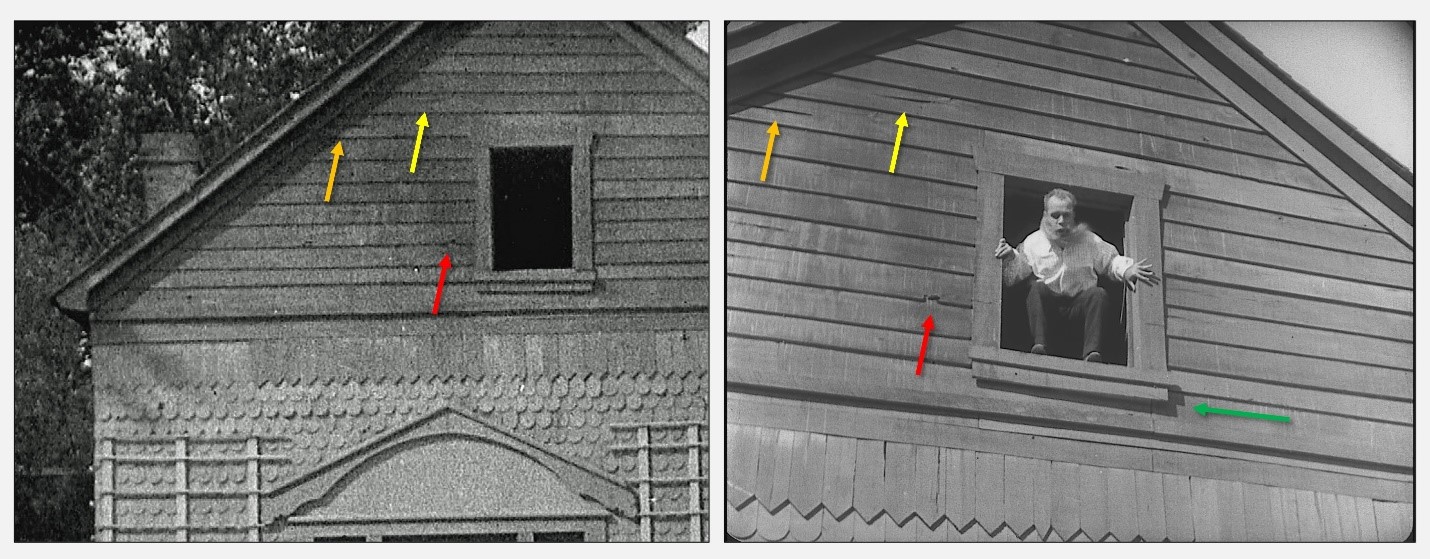

You can see by the way the wall falls that it is on hinges.

In the shots before the wall falls, there is a ferocious wind from all the airplane propellers.

As the wall is falling, there is no wind at all.

A tree on the left side of the screen is swaying violently,

but it is obvious that stagehands

What else do you see?

Kevin Brownlow and David Gill saw what appeared to be a stagehand retreating behind the picture window as the wall begins to fall.

Jack Dragga noticed that it was not a stagehand after all!

He made a video about that, a video that opened my eyes and made me rethink everything.

So what was it that appeared to be a stagehand?

As the wall was beginning to fall, it caused air currents that made the curtains billow in an odd way.

If you think I’m lying, watch it again.

And again.

And again.

And again.

And again.

And again.

And again.

I’m telling the truth.

It is quite obvious that the wall weighs a lot, and if it weighed two tons, that would not surprise me.

But what part of the wall weighed two tons?

The front wall is constructed in two sections.

The tall first story, about 18 feet I guess, is as solid as a rock.

But what about the gable in front of the attic?

Look what happens as it slams to the ground.

It breaks apart into multiple pieces, and all those pieces are small, lightweight, breakaway panels.

If Buster had missed his mark, or if the wall had fallen down out of position,

Buster would have punctured right through the breakaway panel above the jamb,

or below the jamb, or to the right or to the left of the jamb.

He would have emerged with a nasty headache, but he would have emerged.

What looks worrisome is not the gable wall, but that window jamb!

If it had encountered an obstruction, it would have popped out, but still, ouch!

Wood, coming down with that velocity, would have been lethal.

What if that window jamb had hit him on the noggin?

Well, let us take a look at the window jamb.

Oak, maybe? Pine, maybe?

Nope.

Notice that there is no glass in that jamb.

It is a completely empty jamb.

Look how the jamb breaks as it smashes to the ground.

It does not break the way wood would break.

It develops a very small tear, very small, which makes me think of cardboard.

It’s heard to see that tear on video, but look at it in the unit still in Buster Keaton Remembered, p. 163.

The tear is really tiny and it’s blurry, but it is odd, is it not?

It doesn’t look like wood anymore, does it?

Now, I don’t think it was cardboard, but I sure as heck don’t think it was wood!

It was something else, something softer.

Maybe it was foam rubber painted to look like wood?

If you think I’m lying, watch it again.

And again.

And again.

And again.

And again.

And again.

And again.

I’m telling the truth.

Oh. One more thing.

When the guy jumps out of the window jamb, I bet that was shot on a previous day.

I had guessed that he jumped out of a different window jamb embedded into a different wall,

but John Bengtson pointed out that it is the same prop wall.

The distinctive defects are identical.

Behold.

The noticeable difference, which could well be a trick of the light,

is the shadow underneath and to the right of the jamb.

Could it be that the bottom of the jamb was swapped out?

My previous draft of this essay was wrong.

We cannot see the top of the house on screen, and so I assumed it was littered with latches.

John Bengtson reminded me about this unit still, though,

which proves that the trick work was not on the roof.

Now, for the sake of context, think back to the billiard game in Sherlock Jr.

It is a little less than three minutes long.

Did it take a little less than three minutes to film?

No.

It took probably fifty or a hundred hours to film.

Notice that it was not filmed in a single take.

Every move is a new take, cleverly intercut with Erwin Connelly’s reactions

so that we don’t notice that the gag is broken up into numerous different shots.

There must have been more NG takes on that one scene than in any other Buster movie.

Do you agree?

So, with that idea hovering in the background, how was this falling wall filmed?

There were no rehearsals, nor could there have been.

It takes up seven seconds of screen time.

So, does that mean it took seven seconds to film?

No way!

There were tests, of that you can be certain.

An architect designed the house, in collaboration with an effects technician.

They decided where to build this breakaway house on location in Sacramento.

They built the hollow house first and then built a frame for the front wall,

and attached it to hinges.

They had Buster stand on his mark and built a window around him.

They raised and lowered the frame a few times to make sure it would clear him.

Then the real work began.

Think backwards: Accept the end result as a given, and try to figure out how you would get there from scratch.

If you wanted to shoot that scene, how would you do it?

I’ll tell you how I would do it.

I would instruct the construction crew to make three identical front walls.

Then I would call a skeleton crew to come in on one or two Sundays when everybody else is at home.

They would build a

Eleanor, interviewed in Buster Keaton: A Hart Act to Follow, said,

“He had been arbitrarily turned over to MGM, he was having problems at home, one thing and another,

he had reached the point where he really didn’t care that much.”

I wish I could hear her entire statement to gauge the context.

Was she really talking about the falling wall?

Or was she talking about something else?

I suspect she was not talking about the wall at all.

I bet she was talking about his drinking and his defeatist submission to MGM’s dictates.

Whatever the case, Eleanor got much of her information (and misinformation) from subsequent researchers,

not always from Buster himself.

That led to some honest mistakes, mistakes that have contaminated the information supply.

Jeffrey Vance in Buster Keaton Remembered and various other sources as well

maintain that the falling wall was shot just hours after Joe Schenck told Buster that he was closing the studio.

Evidence? Evidence? Evidence? Anybody have evidence?

I have my doubts about that story.

It doesn’t fit the other sources.

Jack Dragga’s nice little video, All about the Wall, investigated what really happened.

For that nice little video, Jack pulled an excerpt from a CBC (Canadian Broadcasting Corporation)

TV game show called “Flashback,”

on which Buster appeared on Sunday, 10 October 1965.

A panelist asked how the stunt was done.

Buster replied, simply, “We did it!”

Another panelist asked if he and his crew measured things first.

”Doggone right we measured it!”

A third panelist mused about the rehearsal time.

Buster cut him off: “No rehearsal for those.

You hinge that

Jack also played an excerpt from an audiocassette interview with

Robert “Slim” Gregg, conducted by Joel Goss on 26 May 1986:

“Well, I’ll give you, give you the

I see problems with Slim’s recollections.

To begin with, this house was not built on Romaine Street in Hollywood!

As John Bengtson says — and proves! —

this house “was built on the south end of the Sacramento River Junction set, with other sets in the background.”

John further explains:

“When Buster ‘flies’ grasping the tree and lands in the river,

the camera pans the full length of the set, starting with the collapsing wall house to the left, until Buster splashes down.

Beyond doubt this famous stunt was filmed in Sacramento.”

Slim’s idea about ropes, well, that doesn’t seem right to me.

It would be humanly impossible to synchronize that perfectly,

but perfect synchronization would be crucial else the wall would fall unevenly.

He remembered that the wind machine blew the wall down,

but, as we can see on the screen, the wind machines were all shut off at that moment.

Is this a case of a scrambled memory?

I think not.

This was a case of an

As we can see on our computer screens, the propellers were shut off before the wall fell and were not turned back on until later.

It was not the wind machines that blew the wall down.

The wall was already tilting down.

Gravity should have pulled the wall down.

But John Bengtson noticed a detail that had entirely escaped me:

A tug on a cable brought the wall down!

Note the cable dangling from the left base of the gable.

To my mind, that cable reveals that this was not the first attempt at dropping the wall.

The drop had been tested with previous walls,

and the crew members added the cable once they discovered that gravity was insufficient for their purposes.

John continues:

So much for Skip’s story.

The details gave some seeming authority to Skip’s explanation,

but those details derived from other trick sets, not from Steamboat.

Oy vey. I can see it coming.

What?

The accusation that I am being selective with the evidence.

Okay. Fine.

Let’s look at the two pieces of evidence that I am omitting.

The first is an interview that

Harry T. Brundidge conducted in early November 1928,

just as Buster was getting ready to act in his first talkie, which turned out to be a silent, Spite Marriage.

Brundidge returned home to St. Louis at the start of

January 1929 and published his series of interviews, one by one over the course of the next year,

in The St. Louis Star.

Buster’s instalment appeared about a year after it was conducted, on

30 November 1929.

Brundidge then collected all these newspaper pieces and stitched them together into a book,

Twinkle, Twinkle, Movie Star (NY: E.P. Dutton & Co.,

5 August 1930),

and Buster’s interview appeared on pages 205–211.

Because Buster’s speech was delightfully colloquial,

the text was heavily

The other evidence I am omitting is from

“This Is Your Life” of 3 April 1957.

When Ralph Edwards shows the scene of the falling wall, Buster is so startled that he jumps.

That was

So there. Those are the two pieces of evidence that I suppressed because I don’t want you to know about them,

because I am writing a tendentious essay and wish to mislead you.

I think that by now you can understand why, yes?

We see what we see on that screen.

What we see on that screen is a magic trick.

We now have a tool that nobody had in 1928: frame by frame on our little computer screens in our living rooms.

We can see the basics of how the trick was performed.

So, please, world, I beg of you, stop saying that

Buster risked his life for a laugh.

That is so wrong, wrong, wrong, wrong, wrong.

Please let us put an end to this baseless urban legend.

|

Further Research |

|

An impressive article/interview is published as chapter 43 of Kevin Brownlow’s

The Parade’s Gone By... (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1968).

|

|

The best book about Buster Keaton’s life is Oliver Lindsey Scott’s superb,

seductive, and encyclopedic

Buster Keaton, the Little Iron Man

(New Zealand: privately printed [1995]), but it’s no longer available except at libraries.

What made it so good?

Simple: Oliver gathered every sentence that Buster was ever known to have spoken, stitched them all together in chronological order,

and ran the result by Eleanor, who supplied a running commentary.

That makes this book a unique primary source of inestimable value.

(Eleanor’s running commentary had the occasional glitch, a few failures of recall, and tiny little bits of inadvertent misinformation.

Surprisingly, she said that Buster was 5'6" when he was in fact a bit under 5'4".

Some of what she said was based not on her conversations with Buster, but on things she had heard from others or on things she had read.)

The problem is that Oliver died before he could get most of the copyright clearances, and so he ran off only a handful of copies, informally,

and charged an arm and a leg.

Busterphiles, most of them anyway, have declared undying hatred of this book,

but I assume what they really hate is the peculiar behavior of Oliver Scott.

Well, yeah, hey, he was pretty darned peculiar, often annoying, true, but his book is magnificent.

He asked if I would take it over, and I said nothanx, and now I sorta regret that.

Maybe the reason he offered was because he knew he was dying?

I really don’t know, though.

I nothanxed him because the copyright situation was quicksand.

My fear was that the copyright clearances would entirely consume the remainder of my life and that even then nothing would ever be resolved.

|

|

Rudi Blesh’s Keaton (New York: Macmillan, May 1966)

and Buster Keaton’s autobiography

(as told to Charles Samuels), My Wonderful World of Slapstick (Garden City, N.Y.: Doubleday & Company, January 1960)

are both worth reading, and both give a good impression of who Buster was and what he was and why.

Blesh’s book has a major problem, though.

His publisher rejected the book unless he cut it down to about a half or a third its size.

He refused, and thus ensued arguments and fights.

At long last, he surrendered.

Unfortunately, Blesh had never had any interest in what happened after silent movies were shut down at the end of the 1920’s.

Just before going to press, he hastily scribbled some brief chapters about Buster’s life from 1933 through 1966,

and he got lots wrong.

Now, Blesh tape recorded his conversations with Buster and Buster’s fam and friends.

Those tapes have vanished.

His original typescript?

Vanished without a trace.

If you can find those materials, you will be showered with praise from the whole world.

|

|

The best book on Keaton’s work is Jim Kline’s

The Complete Films of Buster Keaton (New York: Citadel Press, 1993).

David Macleod’s

The Sound of Buster Keaton

(London: Buster Books, 1995), which deals only with the post-independence work, is also highly recommended.

Daniel Moews’s Keaton: The Silent Features Close Up

contains an invaluable final section entitled “Bibliographical and Filmographical Comments.”

Alan Schneider wrote a self-deprecatingly

hilarious and touching description of his work with Keaton

in an essay called “On Directing Film.”

Keaton, dismayed by what he thought was an insane script,

was not his usual joking and laughing self on the set, but taciturn and subdued,

giving Schneider the wrong impression

that the somber attitude he adopted for Film was a carry-over from real life.

This essay is included in Samuel Beckett’s Film: Complete Scenario / Illustrations / Production Shots

(New York: Grove Press / Evergreen, 1969), and was later republished, with a few modifications,

as “The Sam and Buster Show, 1964–1965,” a chapter in Schneider’s unfinished autobiography

Entrances: An American Director’s Journey (New York: Viking Penguin, 1986).

(Among the people who despise Schneider’s essay and find it dishonest:

Eleanor Keaton, Oliver Scott, Jim Karen who worked both with Schneider and Keaton,

and every Buster fan I’ve ever met.

So I’m completely alone in my judgment on this one,

but I can’t find anything dishonest about it and I think it’s a wonderful source.)

|

|

More recently, Eleanor Keaton and Jeffrey Vance published

Buster Keaton Remembered,

a lovely coffee-table book with fascinating text and never-before-published photos.

|

|

And then when you begin to wonder about all the contradictions in the various accounts,

a great remedy is Patty Tobias’s wonderful essay,

“The Buster Keaton Myths.”

|

|

A delightful and intensively researched booklet on the Actors’ Colony,

which Buster’s father helped found just outside of Muskegon, Michigan,

and where Buster had his happiest childhood memories, is Marc Okkonen and Ron Pesch’s

Buster Keaton and the Muskegon Connection: The Actors’ Colony at Bluffton, 1908–1938

(Muskegon: privately printed, 1995; available through the Muskegon Mercantile).

Marion Meade, whose atrocious and offensively inaccurate book,

Buster Keaton: Cut to the Chase

(working title: Quiet! The Tumultuous Life of Buster Keaton),

infuriated Keaton’s family and friends,

has nonetheless done the world a service by making her research material, including the interviews she conducted, available at the

University of Iowa Libraries’ Special-Collections Department.

I’ve not seen this collection for the simple reason that my cat told me not to travel so far ever again.

If she ever changes her mind, I would head out immediately to spend a few weeks pouring through it.

|

|

As for Jim Curtis’s book, I have read only parts of it.

Jim found tons and tons of info and lots of amazing little details that I never knew about before,

but when I try to read the way he strings the little factoids together,

I have far too much trouble making sense of the resulting narrative.

Most Busterphiles seem to love his book, though, and, yes, there is much to love.

The endnotes are certainly worth the price of admission.

|

|

Material on the making of The General can be found in some of the above items,

but the best source is The Day Buster Smiled (Cottage Grove, Oregon: Cottage Grove Historical Society, 1998),

which is now, alas, out of print.

|

|

No book gives a sufficient step-by-step of a work day, even though some of this can be reconstructed from news accounts and unit stills.

No book tells in sufficient detail how the physical effects were performed.

No book offers even a conjecture about how the house fell safely in Steamboat Bill, Jr.,

even though the basics are pretty easy to figure out and even though the giveaways were caught on camera.

No book goes into much detail about printing, distribution, promotion, regional exchanges, contracts, gross ticket sales, nut, percentages,

amounts received by the distributors, percentage received by producers, how that was divided, who got paid what and why and when.

No book goes into much detail about the storage and preservation of prints and pre-print materials, about their destruction,

about their rescue and restoration, about their reissues.

And what I wouldn’t give to examine the camera reports, the continuity reports, the daily disbursements, the ledger sheets.

Even if you’ve read everything there is to read about Buster,

most of what is in this online web essay will come as a surprise to you.

It certainly came as a surprise to me as I was stitching it together.

This just goes to demonstrate that the definitive book has not been written — and probably never will be.

|

|

A NEW BOOK!

Available only in Italian translation is Kevin Brownlow’s long-delayed Seeking Buster Keaton.

Definitely worth a read (extremely difficult for me, unfortunately —

when I get a month to myself I’ll force myself to plough through it and maybe finally master a little bit of Italian).

Amazingly, and importantly, this book contains a supplement:

the only authorized DVD edition of Buster Keaton: A Hard Act to Follow.

(And if you’re interested, Kevin also has a new book about Chaplin:

Alla ricerca di Charlie Chaplin.

Wonderful book. Wonderful wonderful wonderful.)

|

The Modern Misperception |

|

Oh heavens to Betsy!

Back around 1989 I openly predicted that it would soon happen, and now it has happened.

Various commentators are condemning The General as

|

|

Wow. What a workout!

For half a century, I have been mentally collecting info about Buster in general and about The General in particular,

but until I wrote everything down and organized it all, I entirely misunderstood what I had collected.

I could never figure out the Killiam story until I plopped it into the timeline.

I could never understand the German story until I plopped it into the timeline.

I never understood what Buster referred to in regard to the British reissue until I plopped it in.

I would have accepted Jim Curtis’s reconstructions as he had them written —

had I not plopped his factoids into this timeline.

In the process of scribbling this ever-growing web essay,

whenever I thought I finally had something figured out,

I learned more and discovered that I didn’t have it figured out at all.

I would have accepted Keith Scott’s story about the 1974 date,

especially since it so nicely dovetailed with my viewing of the Jay Ward version in 1976

and dovetailed further with Warshow’s criticism of 1977,

but when I plop the story into the timeline, the 1974 date falls apart.

I had accepted the alternative 1953 date supplied by Wikipedia,

and it seemed to be confirmed by that newspaper announcement from 1954,

but that fell apart, too, when placed into the timeline.

For decades, I was convinced that James Mason made his discovery by accident,

and for decades, I thought that The Buster Keaton Story was worthless trash unworthy of even a passing thought.

Now I see how the rotten movie led to further film recoveries and awards,

which in turn led to a revival of interest and a new career for Buster and to the German gig

and to the

|

|

— Ranjit SandhuFriday, 27 July 2001 (and occasionally updated)

|

|

Many thanks to Kevin Brownlow for correcting some howling errors!

|

|

THE MORAL OF THE STORY:

Don’t drink. Don’t smoke.

And for heaven’s sake, don’t entrust your business affairs to anybody else!

Not even your best friend. Not even your

|

|

|

|

USELESS NOTE:

In October 1966, my parents would watch The Charlie Chaplin Comedy Theatre on

WOR Channel 9 on Sunday afternoons at 12:30,

but I never saw what was amusing about the show and I never watched more than a few seconds before walking away.

It was a terrible way to be introduced to silent cinema.

So, apart from those few glimpses, I never saw a silent film

until a year later, on the evening of Sunday, 3 December 1967,

when my parents turned on the tube and watched the local TV première of

The Great Chase

on WOR Channel 9 at

7:30.

I was enthralled, especially by that guy with the trains.

I recognized that this was something special, that the movie was much more than funny; it was magical.

A revelation.

|

|

Ah. It comes back to me.

From earliest youth, I have found trains captivating.

I still do.

I have never studied them.

I do not know the history.

I do not know the mechanics.

But I sure like to look at ’em.

Still do.

Once I saw The Great Chase, I noticed that boxes for

|

|

Saturday, 17 February 1973. Since my teacher the year before had spoken highly of Modern Times,

I begged my parents to take me when it popped up at the

Hiland in Albuquerque for a kiddie matinée.

My parents, relieved to find an excuse to be rid of us kids for a few hours, dumped us all off.

The Hiland, of course, massacred the movie by cropping it at .412"×.825", and I was a bit surprised that it was not a silent after all,

but a talkie that mimicked a silent, but I was nonetheless enthralled.

I had not liked The Charlie Chaplin Comedy Theatre,

but I just went wild over this movie, and I raved about it so much that my parents surprised me with a copy of

McDonald, Conway, and Ricci’s The Films of Charlie Chaplin (Citadel, 1965), which I must have then read fifty times.

At the Hoffmantown branch of the Albuquerque Public Library, my mother introduced me to Joe Franklin’s

Classics of the Silent Screen, which she checked out for me and which I read over and over and over and over.

|

|

When we visited Disneyland in April 1973 (Saturday the 21st, I think),

I saw the little cinema with announcements of Charlie Chaplin and so forth, and never had I been so desperate to enter a building.

I spent hours and hours and hours in

the little cinema in

the round that showed 16mm silent movies on continuous loop on six screens.

(How that was done?

Here’s how.)

My parents did not enter with me, as they had zero interest in such things.

|

|

The audience entered on house-right, went counter-clockwise, and exited on house-left.

The ragtime music on continuous loop was great, and how I wish I could remember it now.

|

|

My oh my! You can learn almost anything on the Internet.

The music was excerpts from a Spike Jones album,

“Hangnails Hennessey and Wingy Brubeck playing

Rides, Rapes & Rescues: Themes from the Great Silent Films,” Los Ángeles: Liberty Records, 1961,

LRP 3185.

(Still available, believe it or not.)

Now that I can hear this again, my memory begins to return.

My memory is that four tracks — by far the best four tracks — were edited together, music only, onto a continuous loop:

|

|

Oh it’s so nice to hear that again.

That’s like ballet or gymnastics; it is precision music that demands total concentration and total commitment. Yummy.

This is a direct precursor to Joe Siracusa’s 1970 score for Jay Ward’s reissue of The General.

|

|

I think there was an emergency exit between screens 3 and 4, but I really don’t remember.

My memory, which may well be wrong, is that the music emanated from some sort of large box placed on the floor

just outside the raised-and-railed center of the floor, facing the emergency exit.

|

|

The films were, right to left around the circle:

(1) The Rounders (2) Steamboat Willie (muted) (3) The Great Train Robbery (4) Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde (1911 version with James Cruze) |

|

(5) (I don’t remember. Sorry.

Online

sources suggest some possibilities, but not a single one of them jogs a memory,

and I don’t think it was any of these:

Gertie the Dinosaur,

A Dash through the Clouds,

A Trip to the Moon,

Fatima’s Dance,

Dealing for Daisy,

Dizzy Heights and Daring Hearts,

Two Wagons — Both Covered,

The Noise of Bombs,

Shifting Sands,

Crashing Through,

the first reel of The Hunchback of Notre Dame,

but whatever it was, it didn’t tickle my fancy; if it was one of these, then it may have been Gertie,

but I recall first seeing that many years later; much more likely, it was A Trip to the Moon,

but, if it was, then why was I not enchanted by it?),

and

|

|

(6) a reel of animated glass-lantern slides.

I would so love to see that particular slide collection again, but I have never been able to identify it or locate it.

“WE USE ONLY SAFETY FILM IN OUR THEATRE” said one slide as it caught fire.

The “COMING ATTRACTIONS” slide made me burst out laughing uncontrollably,

so much so that I nearly fell onto the floor.

It was illustrated not by pretty showgirls,

but by a pair of elderly grannies, sitting in chairs, looking stern, wearing all black.

My sisters and their visiting friend who traveled with us

could not understand why on earth I found that amusing, and they left pretty quickly.

Come to think of it, NOBODY laughed or even chuckled at any of the slides except for me.

This reel of slides might have been “Intermission Slides from Nickelodeon Days.”

I remember that it was about five minutes long, and so it might have been the following two items spliced together,

though it would surprise me if Disneyland would run 8mm rather than 16mm.

I see from

later Blackhawk catalogues that these two parts were indeed run together as a single 100' reel.

|

|

Except for Steamboat Willie, the films were all from

Blackhawk of Davenport.

I skipped Jekyll, even though a little voice in the back of my head was telling me to watch it just for the historical interest,

I couldn’t help but catch lots and lots and lots of glimpses of it, though, which I still remember vividly;

I saw Steamboat just twice, I think; it was obviously a talkie but it was shown without sound;

I watched The Great Train Robbery probably four times, the slides probably six or seven times, and The Rounders as often as I could.

I just adored that movie (and still do).

I found that The Rounders was simply addicting.

I remember that a wife remarked to her husband that the music perfectly fitted only the Chaplin film, not so much the others.

I had noticed precisely the same thing, and was glad to overhear it from a total stranger.

To be surrounded by those images and that music was the highest high I had ever experienced,

and the pleasure was so extreme I never wanted it to stop.

After about four hours, my parents finally lost all patience,

stood outside the exit door, called for me to get out of there right away, and that was the end of that.

Oh how I hated to leave.

|

|

As soon as we got back home a few days later,

I looked up Blackhawk

(probably at the

Hoffmantown library, probably via help from the reference librarian,

probably in a Davenport phone book, but, really, I don’t remember).

I wrote to ask for a catalogue, begged for an 8¢ stamp,

walked to the Post Office, and about two weeks later went totally wild.

I drooled over all

the listings, though I had no money at all.

Finally, my mother somehow scraped together about $25 and purchased the shortest abridgment of The General for me.

|

|

Then a private film society called

Moving Pictures Ltd presented the silent 16mm Killiam print

at The Guild

in Albuquerque,

Saturday morning, 25 January 1975.

I attended both screenings, dead silent. No accompanist.

Moving Pictures Ltd and The Guild were not aware that silent films were supposed to be accompanied by musicians.

The pair of

Bell & Howell 16mm Filmosound projectors with 1000W incandescent bulbs gave the dimmest picture,

but I finally got to see pretty much the whole movie,

and the thirty or so other people in the auditorium all went wild over the movie,

which they had clearly never seen before.

They spoke excitedly with one another about what they had just witnessed,

and most of them stayed to see it again at the second screening at noon.

The laughter wasn’t quite as boisterous the second time round, but it was genuine.

I spent the next few months trying, trying, trying so hard to replay the movie in my mind,

repeatedly, every day.

Oh. I just remembered.

Though it was a Killiam print, it opened with a color Films, Inc. logo,

this one.

That was the first time I had ever seen that logo,

but it was run without the sound, of course, and at 16fps.

|

|

After more than a year of trying, my mother finally scraped together another $20 or so,

and I traded in the short version for the long version,

which I watched over and over and over and over and over again.

|

|

Saturday and Sunday, 10 and 11 April 1976, The Guild presented the Jay Ward version of The General

doubled with Sherlock Jr. in 35mm, but cropped them at 1:1.66U, .497"×.800" and wildly misframed,

rendering both films incomprehensible.

There were never more than four or five other people in the auditorium, and nobody enjoyed the films.

I watched each film four times over the two days, despite the insane cropping,

partly because I knew what was happening in the sections that were lopped off,

and partly because I didn’t know when or even if I’d ever be able to see 35mm prints of these films again.

Sherlock Jr. returned multiple times in 16mm at UNM, always with Rohauer’s mutilations,

but the Jay Ward edition of The General never returned to Albuquerque.

Three days, wretchedly presented, with never more than maybe five people in the audience,

and then it was gone from the city forever.

|

|

Oh my heavens!

Here we go:

I watched each movie twice on Saturday and twice again on Sunday.

Sherlock 3:15, The General 4:15,

Sherlock 6:00, The General 7:00.

|

|

Ira Jaffe loved The General and presented it in his UNM classes whenever he could,

and one time I paid my

|

|

When Blackhawk offered the Killiam feature edition of The General on VHS, I purchased a copy,

and, at last, it had nice piano music on it, by

Bill Perry.

I watched it countless times.

|

|

Buster Keaton: A Hard Act to Follow was shown on PBS, and I was intrigued by the clips from The General,

which were clearly cut in from a

|

|

Kino on Video “Collector’s Edition” series, 1989–1992

(Some of these were also issued on laserdisc from Image Entertainment)

|

30 Oct. 1989, $29.95 Cropped; 24fps; same library music as 1952 Film Renters Inc. edition; remade titles throughout (This particular transfer of this particular edition was not issued in any other format.) |

30 Oct. 1989, $29.95 Steve Sterner on the piano  Also on “The Silent Classics” LD

Also on “The Silent Classics” LD |

30 Oct. 1989, $29.95 Gaylord Carter on the Wurlitzer, 1978; probably Bill Everson’s 35mm print (This particular transfer of this particular edition was not issued in any other format.) |

30 Oct. 1989, $29.95 Cropped; Konrad Elfers’s 1965 (This particular transfer of this particular edition was not issued in any other format.) |

30 Oct. 1989, $29.95 Cropped; Gaylord Carter, Wurlitzer  Also on “The Silent Classics” LD |

30 Oct. 1989, $29.95 Steve Sterner, piano (This particular transfer of this particular edition was not issued in any other format.) |

9 Nov. 1989, $29.95 Torbjorn Iwan Lundquist, Malmo Symphony Orchestra  Also on “The Silent Classics” LD |

9 Nov. 1989, $29.95 Adolph Tandler, Los Ángeles Symphony Orchestra, 1932  Also on “The Silent Classics” LD |

9 Nov. 1989, $29.95 Gaylord Carter, Wurlitzer  Also on “The Silent Classics” LD |

9 Nov. 1989, $29.95 Joseph Turrin, original Kino score for 18 players  Also on “The Silent Classics” LD |

15 Oct. 1990, $39.95 Jacques Gauthier, piano, based on 1914 cue sheets  Also on “The Silent Classics” LD |

15 Oct. 1990, $29.95 Steve Sterner, piano  Also on “The Silent Classics” LD |

15 Oct. 1990, $29.95 Blackhawk’s anonymous orchestral score  Also on “The Silent Classics” LD |

15 Oct. 1990, $29.95 Gaylord Carter, Wurlitzer  Also on “The Collector’s Edition” LD |

15 Oct. 1990, $29.95 Steve Sterner, piano  Also on “The Silent Classics” LD |

15 Oct. 1990, $29.95 Roy Brubacher, organ  Also on “The Silent Classics” LD |

15 Oct. 1990, $29.95 Gaylord Carter, Wurlitzer  Also on “The Silent Classics” LD |

15 Oct. 1990, $29.95 François Chevassu, musical director, 1981: Robert Viger (quartette), Alain Bernaud (solo piano), Franz Schubert “Sonata for Arpegionne” and “Quintette in C”  Also on “The Silent Classics” LD |

21 Oct. 1991, $29.95 Windowboxed; Alexander Rannie and Brian Benison, ensemble, 1991  Also on Blackhawk/Image LD |

21 Oct. 1991, $29.95 Gaylord Carter, Wurlitzer  Also on Image “Special Edition” LD |

21 Oct. 1991, $29.95 Timothy Howard, organ  Also on Image/Blackhawk LD |

21 Oct. 1991, $29.95 Windowboxed, remade titles  Also on Image/Blackhawk LD |

21 Oct. 1991, $29.95 Gaylord Carter, Wurlitzer  Also on “The Silent Classics” LD |

8 Jul 1992, $29.95 John Muri, Wurlitzer  Also on “The Silent Classics” LD |

8 Jul 1992, $29.95 John Muri, Wurlitzer  Also on “The Silent Classics” LD |

|

|

|

HBO/Thames “Legendary Silents” series, 1989, 1991

|

8 Nov. 1989, $39.99  Also on “The Silent Classics” LD |

8 Nov. 1989, $39.99  Also on “The Silent Classics” LD |

8 Nov. 1989, $39.99  Also on “The Silent Classics” LD |

8 Nov. 1989, $39.99  Also on “The Silent Classics” LD |

8 Nov. 1989, $39.99  Also on “The Silent Classics” LD |

8 Nov. 1989, $39.99  Also on “The Silent Classics” LD |

25 Sep. 1991, $59.99 |

|

Some of the above “Legendary Silents” from Thames Television

were shown on PBS as episodes of “Great Performances.”

I distinctly remember that “Great Performances” slightly abridged The Thief of Bagdad.

Another that I remember was Broken Blossoms.

As for Buster, Our Hospitality was shown, but

I missed it because I didn’t know about it. Darn!

But The General was not included, for whatever reason.

|

|

HBO/Thames “Harold Lloyd Comedy Classics” series, 1990

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

As you can see, the above films no longer belonged to the studios that had financed them.

They had been bumped around from distributor to distributor and some were in the public domain.

Kino and HBO licensed whatever rights they knew about and issued their own copies.

As for the studio that still owned rights to its own films,

Paramount Pictures issued nine on VHS and at least a few also on laserdisc:

|

|

Paramount, 1985–1992

|

Wings VHS 2851, Feb 1985, $49.95  Also on Paramount LV2851-2 1985, $39.95 |

Running Wild VHS 2744, 03 Jun 1987, $29.95 |

The Last Command VHS 2785, 03 Jun 1987, $29.95 |

The Ten Commandments VHS 2506, 03 Jun 1987, $29.95 |

Old Ironsides VHS 2786, 03 Jun 1987, $29.95 |

The Docks of New York VHS 2807, 03 Jun 1987, $29.95 |

The Wedding March VHS 39501, 03 Jun 1987, $29.95 |

The Covered Wagon VHS 2501, 17 May 1990, $14.95  Also on Paramount LV 2501, 17 May 1990, $34.98 |

The Sheik VHS 2680, Jun 1992, $24.95 |

|

MGM/UA “Silent Classics,” 1992–1998

|

The Big Parade M301356 VHS, 08 Nov 1988  ML101356 LD, 12 Feb 1992, $39.98 |

M301474 VHS, 08 Nov 1988  ML101474 LD, 1989, $39.98 |

The Crowd M301357 VHS, May 1989, $29.95  ML102217 LD, 31 Dec 1991, $49.98 |

The Wind M301359 VHS, May 1989, $29.95  ML102217 LD, 31 Dec 1991, $49.98 |

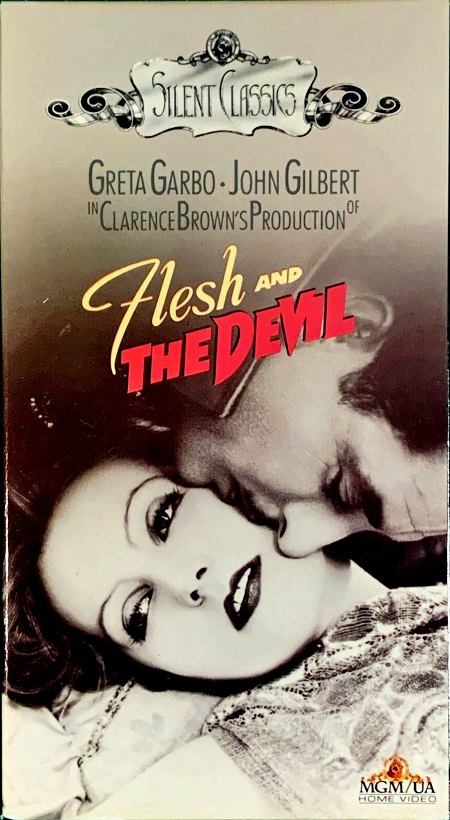

Flesh and the Devil M301358 VHS, May 1989, $29.95  ML102339 LD, 19 Feb 1992, $99.98 |

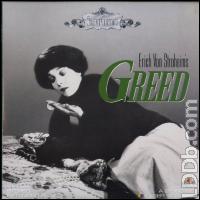

Greed M301360 VHS , May 1989, $29.95  ML101360 LD, 1990, $39.98 |

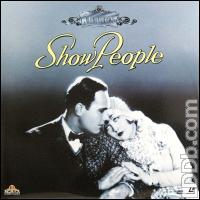

Show People M301539 VHS, May 1989, $29.95  ML101539 LD, 07 Jul 1997, $39.98 |

The Cameraman M302159 VHS, 20 Feb 1991, $29.98  ML102225 LD, 29 Jul 1992, $39.98 |

The Student Prince in Old Heidelberg M302160 VHS, 20 Feb 1991, $29.98  ML104505 LD, 29 Sep 1993, $49.98 |

A Woman of Affairs M302161 VHS, 20 Feb 1991, $29.98  ML102161 LD, 10 Dec 1992, $34.98 |

Don Juan M302162 VHS, 20 Feb 1991, $29.98  ML102162 LD, 10 Apr 1991, $39.98 |

The Mysterious Lady M302299 VHS, 19 Jun 1991, $29.99 |

Spite Marriage M302300 VHS, 19 Jun 1991, $29.99  ML102225 LD, 29 Jul 1992, $39.98 |

Our Dancing Daughters M302210VHS, 19 Jun 1991, $29.99  ML104508 LD, 29 Sep 1993, $39.98 |

The Single Standard M302209 VHS, 19 Jun 1991, $29.99  ML102858 LD, 24 Mar 1993, $44.98 |

The Kiss M302259 VHS, 19 Jun 1991, $29.99  ML102858 LD, 24 Mar 1993, $44.98 |

Wild Orchids M400495 VHS, 1991  ML105728 LD, 18 Feb 1998, $89.98 |

The Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse ML104758 LD, 14 May 1997, $49.98. |

|

and maybe a few others, too, but I think that was it.

Customers could feel safe, then, about movies purchased from Kino and HBO and Paramount and MGM/UA.

Customers were much more wary of silent movies available on video from most other sources.

|

|

The HBO cassette of The General came in the mail and I was in heaven.

I showed it to everybody I could, and a bunch of people really liked it. A lot.

They had not been at all familiar with it, but they were entirely won over by the movie.

Some acquaintances, though, thought it was okay, but nothing more than that.

It was not something they would want to watch a second time.

They preferred Star Wars.

Others, of course, did not like it at all and found it painful.

Reasons? “Black and white is stupid. Who are these actors? It’s old!”

|

|

One friend had an extremely strange reaction.

He had not heard of Buster Keaton, and so I suggested we watch a movie.

“Who was he?”

“He was a comic from the twenties.”

Response: “I prefer Chaplin.”

What a bizarre response.

Was this a contest?

Had he already decided that he preferred Chaplin to any other possible comic and so dismissed all others out of hand?

I really didn’t understand.

So we agreed on an evening and I showed him the movie.

He was distracted.

He kept looking away at other things and missed the reveal that the engine’s nameplate was GENERAL.

He missed the title that explained we were now “A year later.”

So he was totally lost with the story.

When he saw that Buster’s character tried to enlist in the Confederate army,

he got worried: “Was Buster a Southern sympathizer?”

“No,” I assured him.

When it ended, he gave his judgment:

“I prefer Chaplin.”

That killed the conversation, killed it dead.

|

|

So typical. So predictable.

This is why I prefer not to talk with most people anymore.

The conversations get derailed before they even begin,

and preconceptions do not merely color the conversation, but entirely suffocate it.

I guess this is why some people have said that I’m a poor conversationalist.

Like when AIDS first burst upon the scene.

Apropos of nothing, a coworker asked what my thoughts on it were.

I began to say something like,

“It might be because we’re doing things now that have never been done before....”

I meant to continue by saying that, among countless other things, we are deforesting the planet,

which disturbs microorganisms that should never be disturbed.

But I never got that far.

As soon as I completed that introductory sentence,

the other person burst out, “Damn right!” assuming that I was referring to sexual peccadilloes.

And that killed the conversation, killed it dead.

All the time, all the time, all the time. Exasperating.

Why even talk? To anybody? About anything? Ever?

|

|

Around the year 2000, some college-age interns at work asked who this Buster Keaton was whose pictures adorned my office.

We agreed to meet after work the following Monday.

I brought in my

|

|

Then there’s a long story, but, in a nutshell, some friends included The General in their

downtown Buffalo film series,

and I made sure that it would be shown properly, without cropping.

(I purchased an aperture plate with my own money and brought along my own lens.

People were amazed that the aperture arrived just a few days after I placed the order.