THE WORKS OF TINTO BRASS

A Clockwork Orange

(Arancia meccanica,

1968–1969)

Forthcoming book that includes the story

of the failure to produce Tinto’s version of A Clockwork Orange.

|

NEROSUBIANCO’s world première at the same time as

and in conjunction with the

Cannes festival in May 1969

(1969, 1969, 1969, 1969, not 1968, when I wrote 1968, I was wrong, it was 1969)

and it made an impression on some bosses

over at Paramount Pictures, who immediately flew Tinto Brass

to Hollywood for negotiations, and then explained that they

wanted him to direct a film version of Anthony Burgess’s

novel, A Clockwork Orange. As only a few people know,

screenwriter Terry Southern had initiated negotiations to film

Burgess’s novel with Mick Jagger playing the lead part of

Alex and the other Rolling Stones playing his droogs, and a

British photographer by the name of Michael Cooper directing,

but this never came to be, possibly in part because of a

deception concerning claims to rights. One by one, photographer

David Bailey, cinematographer (lighting cameraman) Nicolas Roeg,

and directors John Boorman and Ted Kotcheff were approached to

direct the film, but other things got in the way.

One report claims that Burgess himself thought Ken Russell would be a good choice for

director, yet another report states that Burgess dreaded the thought of receiving the Russell treatment.

At least one report claims that Russell seriously

considered the project, but ultimately rejected it in favor of

The

Devils, a harrowing tale of Buffalo’s real-estate

developers. When it came Brass’s turn to take up the mantle,

he bungled the deal by saying that he would indeed love to make

A Clockwork Orange, as he admired the book,

but only on condition that Paramount first produce L’urlo.

That was the end of that job.

Well, that was the story that Tinto told, but it was not true.

Tinto is not a liar, but he does sometimes misremember, and whoah did he misremember!

I am ashamed of myself for not having caught a major discrepancy.

Someone (who shall remain nameless, at least for now) pointed the discrepancy out to me,

and I was stunned, totally, totally stunned.

That was right! The story Tinto told was impossible.

You see, the filming of L’urlo was completed in 1968

and the editing was completed at the beginning of 1969.

By the time of the negotiations with Paramount in May or June 1969, L’urlo was done.

So there was no way on earth that Tinto would have asked Paramount to finance L’urlo.

Could it have been another movie?

Not likely.

Tinto had a few projects under consideration, projects that never came to fruition,

but involvement of Paramount was probably not even a thought.

So what really happened?

I bet I know.

The censor board at the Ministero del Turismo e dello Spettacolo had banned L’urlo,

and Tinto and his cast and crew petitioned to have the ban overturned.

What’s more, Michelangelo Antonioni and others signed their own petition to get the ban overturned.

Under pressure, the Ministero agreed to withdraw its ban and allow the movie to be shown freely, without restriction,

but only under one condition: They got Dino De Laurentiis to promise not to release it.

So, the film was no longer banned, but De Laurentiis was not allowed to show it to anybody.

And when you understand that, you can see the source of Tinto’s misrecollection, the trick that his memory played on him.

Tinto didn’t ask Paramount to underwrite L’urlo; he asked Paramount to buy out the distribution contract!

Coincidentally, the hotel in L’urlo

displayed a giant logo for Paramount Pictures, which makes me quite curious.

L’urlo got its world première at

the Berlin Film Festival in June/July 1970.

It was a success and it was going to win the top award, but then Vietnam protests closed down the festival

and that was the end of that.

Then Tinto, like most of us, got

punished for losing. See a still below, in the entry for

Dropout,

which was made a year before Kubrick’s film, to see where

some of the props came from!!!!

Years later Tinto hearkened back to A

Clockwork Orange a little bit — just a little bit. In

Action (1979) a gang of masked punks attacks the three

lead characters. And then Snack Bar Budapest (1988)

deals with all manner of gangland violence, with the town boss

played to perfection by the teenaged François Négret. (In

Kubrick’s film, Malcolm McDowell at the ripe age of 27 was

hardly convincing as a 15-year-old delinquent.) Unlike Kubrick,

Tinto never tries to make watching the violence an unbearably painful

task. He gets the point across without bludgeoning the audience. Further,

Tinto has a much more positive view of human nature than Kubrick

ever had. So I wish he had been retained to make the movie. Oh well....

HOW CONFUSING CAN IT BE? Well, I showed an

earlier version of the above summary to Alex Thrawn, who runs the

Malcolm

McDowell web site, and he told me that I was entirely wrong. So I

did some research. My conclusion: I can’t make head nor tail of

the story. Anthony Burgess, Terry Southern, Rolling Stones manager

Andrew Loog Oldham, Stanley Kubrick, Si Litvinoff, Tinto Brass, and

others tell such wildly conflicting stories that I have decided it

best just to give up — at least for now. So I hereby reprint the

main sources. Hope you’re in the mood to get a headache.

You’ll see what I mean. If you can get to the bottom of it all,

please let me know. Thanks! And good luck!

What Those in the Know Have Had to Say

about the Production of

A Clockwork Orange

|

Extract from an unwritten reference book

on British cinema in the 60s: “A Clockwork

Orange (1967, UK). Directed by Michael Cooper.

Produced by Sandy Lieberson, Si Litvinoff. Screenplay

by Michael Cooper and Terry Southern, from the novel

by Anthony Burgess. Starring Mick Jagger as Alex,

with Keith Richards, Brian Jones, Bill Wyman and Charlie

Watts. Score by Jagger/Richards, performed by the Rolling

Stones...”

It almost happened. As Sandy Lieberson

recalls, it all began when his photographer friend Michael

Cooper, who had shot the Peter Black cover for Sgt.

Pepper, introduced him to the novel. “I thought,

‘My God!...’ I had to go back and read it a

couple of times, but I was stunned by the power of it, so I

made enquiries into the rights.” Burgess’s agent

put Lieberson on to Si Litvinoff, who at that time was Terry

Southern’s lawyer, and who had optioned the book with

his business partner Max Raab for just a few hundred dollars.

“I knew Si,” Lieberson continues, “so I

approached him and said, lookit, I’d like to put a film

together with Michael Cooper as writer and

director.”

For a while things proceeded swimmingly.

“We decided where it was going to be shot, it was

going to be almost all Soho — there was a rawness to

Soho at that point which doesn’t exist today. We

had picked out the site for the Korova Milkbar, which was

some weird kind of Chinese restaurant-bar. It certainly felt

possible to recreate the atmosphere of the book in a much

more gritty, dirty way, more realistic than Kubrick’s

approach.... I also think that our instinct was that the

language had an importance as great as the

visual.”

But the Stones couldn’t find time to

make the film. By the time Kubrick stepped in and picked

up the option — Warner’s handed over $200,000, plus

5 per cent of the profits — everyone had

moved on. Lieberson finally collaborated with Jagger on

Performance, and gave Burgess some work rewriting

Sandy Mackendrick’s screenplay about Mary, Queen

of Scots. Michael Cooper committed suicide in his early

thirties, thus depriving the world, Lieberson believes, of an

exceptional visual talent. Would the Cooper A Clockwork

Orange have been as successful?

“It certainly would have been

unusual — it wouldn’t have looked like

any other film of that time. I think it would have

been good....”

|

I just yesterday (Thursday, 21 April 2016) accidentally landed on this video,

which was without explanation embedded into an unrelated page.

Fearing that I’d never be able to find it again, I copied it.

If you own the copyright, please contact me

and we’ll make things right.

Okay. That got me curious. So here are some further sources:

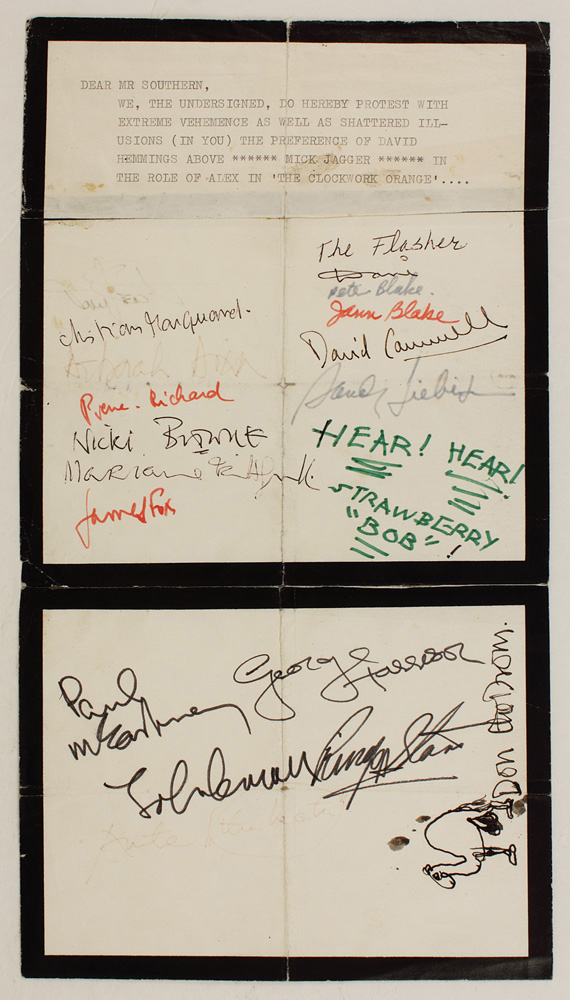

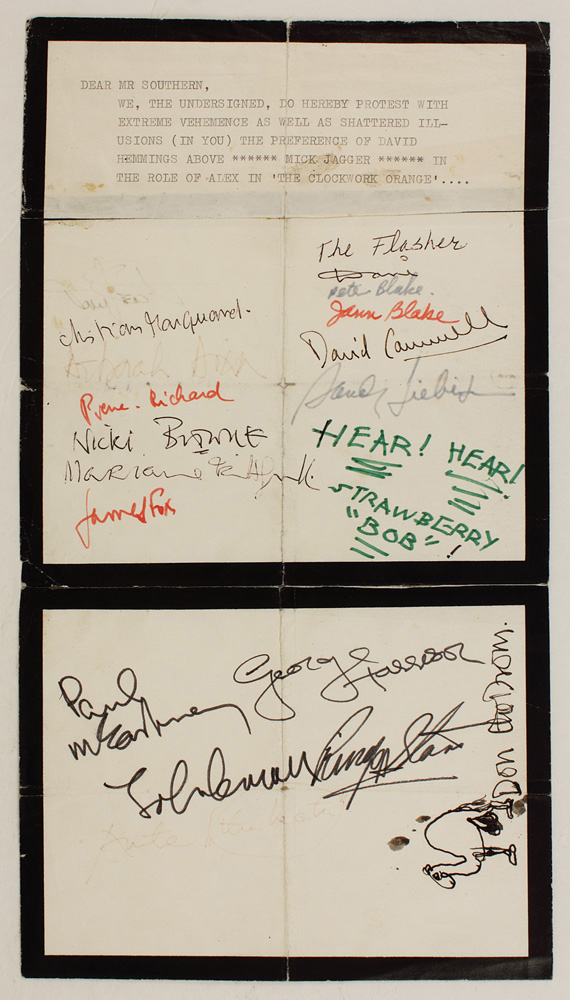

Daniel Kreps, “Mick Jagger’s ‘Clockwork Orange’ Petition Signed by Beatles Up for Auction,” Rolling Stone, Thursday, 15 October 2015

“ ‘Cast Mick Jagger in A Clockwork Orange’: Petition Signed by the Beatles Goes to Auction,” The Guardian, Friday, 16 October 2015

Joe Lynch, “See The Beatles’ Petition for Mick Jagger to Star in ‘A Clockwork Orange’,” Billboard, Friday, 16 October 2015

Make of this what you will.

Fortunately, the petition was reproduced on two of these web pages:

Interesting that James Fox signed this.

At the time, you see, he was working on

Donald “Don the Drom” Cammell’s Performance.

|

There had been an attempt, in the

middle sixties, to put A Clockwork Orange

on the screen, with a singing group known as the

Rolling Stones playing the violent quartet led

by the hero Alex, a rôle to be given to Mick

Jagger. I admired the intelligence, if not the art,

of this young man and considered that he looked

the quintessence of delinquency. The film rights

of the book were sold for very little to a small

production company headed by a Californian lawyer.

If the film were to be made at all, it could only

be in some economical form leasable to clubs: the

times were not ripe for the screening of rape and

continual mayhem before good family audiences.

When the times did become ripe, the option was

sold to Warner Brothers for a very large sum: I

saw none of the profit. There had also been

attempts to make a film of The Wanting

Seed, and I had written several scripts for

it. Script writing can be a relief from the plod

of fiction: it is nearly all dialogue, with the

récit left to the camera. But it is a

mandatory condition of script writing that one

script is never enough. There can sometimes be

as many as twenty, with the twentieth usually a

reversion to the first. In any event, scripts

tend to change radically once they get on the

studio floor.

|

Ibid., pp. 148–149:

|

...and there was talk of filming not

merely A Clockwork Orange but a great deal

of my work. A clothing-store tycoon in America,

movie-struck since he was a kid, was establishing

a production company. He had read all the books I

had written and found them cinematic, even the

brief study of James Joyce. He would begin by

setting up A Clockwork Orange, which the

age of screwing and miniskirts was at last

rendering acceptable for the screen, frontal

nudity, rape and all, and he had his eye on

various directors who would help me to write a

script which should not reproduce the book too

exactly. This was an aspect of film-making which

bewildered me, the unwillingness to stick to the

book. My four delinquents were variously to be

turned into miniskirted girls and violent

old-age pensioners. The serious music crap was

to be eliminated and hard rock substituted. I

was learning a great deal about the film industry,

though not quite enough. One thing I was slow to

learn was the importance of having something

vaguely creative on paper which could be

brandished in the hard faces of film financiers.

An independent producer would prefer to have a

first-draft screenplay to wave, but scripts cost

money. If he could get a treatment for nothing he

considered that he was in business.... My

enthusiasm was, as most enthusiasms are,

unbusinesslike.

|

|

...I knew about Robert Fraser’s gallery

because friends of mine like Claes Oldenburg, Jim Dine,

Larry Rivers and others would show there.... While I

was there, Michael Cooper, the photographer who took

some pictures, said, “You must come over for drinks.

Mick and Keith are going to be there....” I met The

Beatles and Stones at the same time, because Michael Cooper

was doing several of their album covers. He had that market

sewed up.... When Michael Cooper turned me on to that book,

I read it and said this is really good and so cinematic. I

sent the book to Stanley (c. 1966) and said “Look

at this.” He got it and read it, but it didn’t appeal

to him at all. He said, “Nobody can understand that

[invented Nadsat] language.” That was that. The whole

exchange occupied a day. Still I thought someone

should make a movie of this book. At one point I was

making so much money on movie projects that I needed someone

to handle paying the bills. I got involved with this friend

of mine, Si Litvinoff, who had produced some showbiz things

in New York like off-Broadway theatre. He did a couple of

things for me as a lawyer. I showed him the book and told him

how it would make a great movie. He said, “You have

enough money; why don’t you take an option on it?” So I

took a six-month option on A Clockwork Orange for about

$1,000 against a purchase price of $10,000 and some

percentages to be worked out. I wrote a script, adapted it

myself. I thought I’d show the book around, but meanwhile I

would have the script too. After I finished the script, I

showed it around to various producers including David

Puttnam, who was working with various companies like

Paramount. He was one of the people who read the script and

saw the cinematic possibilities of it. In those days, you had

to get the script passed by the Lord Chamberlain [the then

British censor of film and theatre], so we submitted it to

him. He sent it back unopened and said, “I know the book

and there’s no point in reading this script because it

involves youthful defiance of authority and we’re not doing

that.” So that was that. About three years later,

I got a call from Stanley, who said, “Do you remember

that book you showed me, what was the story on that?”

And I said, “I was just showing it to you because I thought

it was a good book, but later I took an option on it.”

He said, “Who has the rights to it now?” What had

happened was that there was a renewable yearly option. I had

renewed once and when it came up for renewal for another thou

I didn’t have the money, so I told Litvinoff I had to drop

the option. So he said “Well, I’ll take it out.” So

he held the rights. So I told Stanley, “As far as I

know this guy Litvinoff has it.” He said, “Find out how

much it is, but don’t tell him I’m interested.” I tried

to do that, but Cindy Decker, the wife of Sterling Lord, my

agent at the time, found out about this inquiry of Kubrick’s,

so she passed the word on to Litvinoff and his friend, Max

Raab, who had put up the money for End of the Road. He and

Raab sold it to Kubrick and charged a pretty penny for it.

Around seventy-five thou, I think.... Well, when I learned

that he was going to make A Clockwork Orange,

I sent him my script to see

if he would like it. I got back a letter saying, “Mr.

Kubrick has decided to try his own hand.” It wasn’t

really a relevant point because it was an adaptation of a

novel. You’re both taking it from the same source.

|

|

Michael turned me onto A Clockwork Orange

and so I took an option on the book and was going to write a

screenplay. Then David Hemmings came out with Blowup

and the agency said “We’ll package this thing with David

Hemmings because he’s hot.” Michael just freaked out and

said “Mick Jagger has got to play this part.” He

drew up a letter edged in black which said: “We the

undersigned hereby insist that Mick Jagger play the

part.” It was signed by all the Beatles, Marianne

Faithfull and Robert Fraser [and addressed to Southern].

I wrote the script and sent it to Stanley Kubrick, who

promptly had some kind of reaction against it and rejected

it. So we started putting it together independently of

Stanley, but what we didn’t realize was that we’d have to get

the script cleared by the Lord Chamberlain, This was normally

a routine matter, but with violence on the streets between

Mods and Rockers, we were at a dicey point in English social

history and the British Board of Film Censors refused to

clear the script on the basis of its violence and bad language.

I dropped the option, and, unbeknownst to me, Si Litvinoff

picked it up. Then I got a call from Stanley asking me what

had happened to the script. It transpired that he had been

putting up the money for Litvinoff to continue the

option — $500 for a six-month option against a purchase price

of $5,000. I asked my agent to find out who owned the rights

but stressed that on no account must she mention that

Litvinoff and Kubrick were interested in it. However, she

couldn’t really resist the temptation to blab and so when the

owners found out who was interested they raised the purchase

price from $5,000 to $150,000. It was a terrible mistake to

tell her and it probably destroyed my relationship with Stanley.

|

|

On reading the book it was like finding

a twin for my madness. I just breathed it and lived off

it; it was a great source of energy. There was just

something in the way of the man — I mean, I was

18 or 19, and it made me think: “I’m

not alone.” It was very easy in those

days to feel alone when you were out there kicking

the doors in, but regardless of what anybody says,

it is nice to have company. And Anthony Burgess

became my company.

We were in the business of getting space, and

so I said we had the rights to A Clockwork Orange,

when in fact we didn’t. It was pure speculation and

energy. The intention to make a film was there but it could

never be a reality. The fact was Burgess had already sold it

for a meager £5,000. Keith went along with it, but

Mick looked down on it — he thought we were just

being little gangsters....

I met Burgess later, in 1973, because I wanted

to buy another of his works, The Wanting Seed. He

told me he had been wrongly diagnosed with a brain tumor in

1959 or 1960 and he chose not to sleep the time away. He

decided he’d better provide for his family, so basically

amphetamines and Scotch put him in the cycle — A

Clockwork Orange, Inside Mr. Enderby, The

Wanting Seed. Because if you look at what the man wrote

before, it’s apparent that an altered state of mind had a

lot to do with it.

|

|

I was separately obsessed with making

a film of A Clockwork Orange, which I had

optioned in 1966 and after much time spent with Nic

[Roeg], knowing that he had written screenplays, was

an extraordinary cinematographer and wanted to direct,

I believed that Nic could be an ideal director of the film,

which I conceived as low budget, that is, if financial

backing had the same faith as I did. I wasn’t getting backing

for the film with such “hot” directors as John

Boorman (after Point Blank) or Ted Kotcheff

with such as Mick Jagger or the then very hot (after

Blowup) David Hemmings and even the promise

of music by some of the Beatles and Rolling Stones who

were fans of the project. So as I continued to try to set it up

and Nic and I continued to talk. One day I got a phone call

from Max Raab who had financed a documentary film,

directed by Academy Award-winning documentary

filmmaker Lewis Clyde Stoumen, for which I had been

his lawyer, saying that he wanted to finance the picture

and was amenable to allowing Nic to direct. Max was an

investor (as was Apple, the Beatles company and

rock-and-roll legends Leiber & Stoller and which

years later George Harrison produced as a movie and in

which recently Ewan McGregor appeared on the London

stage) and thus Associate Producer for a Broadway play

directed by Alan Arkin that I had produced. He was a film

buff and owned a small movie theater in Philadelphia where

he lived. He also was co-owner of a large clothing operation

that had provided him with a vast multi-multi-million-dollar

fortune. And so I was to move to London, first to produce a

film called All the Right Noises starring Olivia

Hussey (her first picture following Romeo and Juliet),

Judy Carne and Tom Bell and introducing Leslie Anne

Down. Ironically it was Nic Roeg who asked that I read the

script [Walkabout] written by a friend of his and

Max Raab who agreed to finance it....

...I continued to develop Clockwork

with screenplays by Terry Southern and Anthony Burgess

with Nic, obviously spending much time with him socially

as well, I ultimately learned from him that he was also

developing a screenplay with a company that was then a

mini-studio called National General and that the rights

were entangled with a company headed by Richard Lester

and that he was frustrated by not being able to get the

go-ahead to make that film, which was his obsession. He asked

me if I would be interested in seeing what I could

do. Having now in my mind that perhaps he wanted to make

this before Clockwork (and before some other works

that I had acquired for him to do in the future), I agreed

to pursue it and was so impressed that I asked Max Raab

if he would finance it and in a great leap of faith he

agreed....

...Stanley Kubrick (who had been given the

novel by Terry Southern, at my request, about five years

earlier), had finally read it and decided that he must direct

Clockwork....

Probably in 1965 or early 1966, while I was

ending practising law (and still producing plays), Terry

Southern, who has been my client and dear friend for

many years and who knew that I was starting to

option books in hopes of beginning a movie-producer

career, suggested that I read an English novel titled

A Clockwork Orange by Anthony Burgess.

I had already optioned several books including

Henderson the Rain King and End of the

Road by John Barth, with the hope that Terry,

who was a hot novelist (Candy) and

screenwriter at that moment (Dr. Strangelove,

The Cincinnati Kid, The Loved One,

etc.) could be proposed by me as screenwriter and thus

get a studio to pay him to write the screenplay and we

could co-produce together. When I read the book (no

easy matter) I was electrified with excitement. All of

my work has been influenced by my love of music and

my history of involvement with the music industry. This

book read like music to me (and, as I later found out,

to some of The Beatles and to some of The Rolling Stones).

The Nadsat language that Burgess created was

musical to me. All of my work has always had a socially

significant underpinning. This black humour book had

that as well. I visualised a movie opening with a futuristic

monolith of a building darkened except for one lit-up

apartment wherein a young man is playing with a snake

and listening to Brahms or Shubert or better still, my

favorite, the chorale, Ode to Joy, from

Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony. I was hooked

and almost immediately started my quest to acquire

the rights (and I also started reading other Burgess books

which I would later option — but that’s another story). Being

able to tell Deborah Rogers, who was the agent for Burgess,

some of the higher-profile clients I represented and some of

the books I had optioned, and being able to tell her that I

wanted Terry to write the screenplay helped enormously. The

fact that no one else was interested (despite all that is in print

of people who say they sought the rights or held the rights)

also helped and by March of 1966 I had the option.

The first option payment in 1966, for one year,

was $1,000. Yes, I know that it has been printed that Burgess in

interviews (Playboy, Rolling Stone, etc.), still

in print, still taken as gospel, said he sold the rights for $500 and

got only a few pennies more. I have the contract if you would

like to print it. Bear in mind that that $1,000 was only for the

first year and Burgess was to receive — and did receive — more

$1,000 payments as well as the full-exercise price payment.

Add those payments to his percentage of net profits, sales of

the suddenly famous book as well as new interest in his other

books and a new career as a screenwriter and celebrity and you

will see how fraudulent his $500-sale-price statement

was — and is. By my count to date he has received and his

estate continues to receive thousands of dollars (well over

$100,000) from the film (not to say the least of what he receives

from book royalties which were close to nil prior

to the film). I also can include the monies he received from

me for options on several of his other books and the payment

he received for a screenplay of Clockwork. And one can

add the sums he suddenly received to write screenplays. In

passing let me explode another myth which appears in a book

about Stanley Kubrick by John Baxter, which states that a

British critic named Adrian Turner saw the Burgess screenplay

and it was more than 300 pages long. More nonsense. The Burgess

screenplay, which I have, is 89 pages long. There is much more

that is incorrect in that book as well as in Lee Hill’s book

Grand Guy Terry Southern, which is loaded with

inaccuracies (including that Terry dropped an option just as

Kubrick agreed to do the picture — he had no option then

as I had the only option from March 1966 on; that David Puttnam

set it up at Paramount, which never happened; that

Paramount put it in turnaround, which never happened; that Max

Raab co-produced The Man Who Fell to Earth, which is

not true, etc. etc.); and out-and-out falsehoods. Film

history continues to be created by third parties who were not at

the dance....

After many failed attempts beginning in

1966 of trying to get financing for the film with Mick

Jagger to star, Terry and I were at the opening party at the

Plaza Hotel for Antonioni’s film Blowup

and we talked to David Hemmings who was an instant hot

new star who was going out to Hollywood to star in Camelot

and he instantly agreed to star in Clockwork. He knew

the book and loved it. A few days later I flew out to LA to see

if I could get his new heat to get financing. I went to the set of

Point Blank, which Chartoff, Winkler and Bernard

were producing, to see if the director John Boorman would

be interested. I had seen a movie he had directed for a rock

group and I was impressed that in my opinion he was able to

make something out of nothing. Despite the fact that

in my heart I really wanted Nic Roeg to direct and Mick Jagger

to star, I was not getting anywhere with the studios with that desire.

Well, again I got a fast yes from Boorman who also knew and

loved the book. It seemed as I would continue to learn, the

English were fans.

Next step was to get Hemmings and

Boorman’s agency, the William Morris Agency,

to know and understand the project (which was obviously

not the usual kind of movie they would normally come

across ) to help sell the package. Luckily the agent was

Joe Wizan, who later on was a successful producer and

studio executive. Joe could read and had taste. But all of

his attempts to get US studio backing were unsuccessful.

Thereafter there were many trips to London

to try my efforts there with the Roeg-Jagger package. The

problem was that the “censor” Lord Trevelyan

would give the film an X rating which would preclude all

of the huge number of Mick’s teenage fans from buying

theater tickets and hence investors were so wary of that

economic loss that they would not finance it. I tried

everywhere, Mick’s agents tried, my agents tried and

tried but no takers. This even with the promise of a music score

by some Stones and some Beatles.

Back in LA , with Ray Wagner we were

co-developing several projects with studios

when he got a “go” on his own film

Loving; so my wife and I decided to sublease

out my then rented Malibu beach house and go back to

our Bridgehampton, Long Island, house for the summer. Soon

thereafter I received a phone call from Brian Epstein, the

manager of The Beatles, saying that he knew of me from

the play that I produced in which the Beatles’ company

had invested and of the project which “the boys”

had told him about and that he would like to meet with me

on his next trip to New York with regard to his desire to

co-produce and finance Clockwork. Well

you can imagine my excitement at the potential of that

partnership for me and for the film. Unfortunately, it was

not to be and before our meeting ever took place Brian was

dead. But it was not too long thereafter that Max Raab called

to say that he was prepared to finance the film as I originally

dreamed, with Nic to direct and Mick to star.

Some time in late 1969 and early 1970 when

we were in preparation I started to receive visits from some

LA-based Warners executives always inquiring about

Clockwork and when our New York lawyer Bob

Montgomery said that a New Jersey accountant had made a

$100,000 offer for the rights for some anonymous person,

I intuited that it was Kubrick, to whom Terry Southern had

given the book many years earlier. He had not read it earlier,

apparently, because the copy Terry gave him was the

US paperback with bikers pictured on the cover and which had

a glossary of the Nadsat language and it was unappetising to

him. Obviously someone had touted it to him all these years

later. Only a few years ago I learned that he was

secretly in touch with Terry with implied promises of Terry’s

draft of a Michael Cooper spec version being used while trying to

get information from Terry. A few years ago Terry’s son

Nile gave me a copy of a letter that Stanley sent

to Terry which illustrates his motives which were predominantly

founded in economic greed and paranoia. It is clear in the letter

he knew, even though I did not at that time, until too late, that

Terry had sold his share of potential producers profits (that I had

voluntarily assigned to him as part of our original arrangement) to

Max Raab for $5,000 and 10% of Max’s profits and what

my Burgess deal was. When I refused the New Jersey deal I knew that I

would hear from someone other than him,

at first, someone to ferret out information in a deceptive manner.

I just continued to go forward preparing for

production until John Calley, a much wiser, more

straightforward intelligence who was a friend of mine and who

was as close to Stanley Kubrick as anyone could be and who

was running Warner Brothers, telephoned me and became the

intermediary for a deal to ultimately be made by us with Warner’s.

Although it was not my original dream, it all turned

well with Nic quickly able to go to his dream, Walkabout,

and Stanley Kubrick making Clockwork, a big box-office

hit....

I have always thought that any of the directors I

had asked to do the picture would do it successfully. The

difference is that they thought it was dark and Kubrick did it

in bright white light....

|

|

“The book was given to me by Terry Southern during

one of the very busy periods of the making of 2001,” he recalled.

“I just put it to one side and forgot about it for a year and a half.

Then one day I picked it up and read it. The book had an immediate

impact.”

|

|

D: Perché

pensasti di usare proprio lui che usciva dall’esperienza

di Arancia meccanica e che era segnato a tal punto da

quel film da divenirne un’icona

personificata?

|

Q: Why did

you think to use (Malcolm McDowell), whose Clockwork

Orange experience of had left a mark on him, making him

an icon personified?

|

|

R: Per spiegare

quello che tu mi chiedi bisogna sottolineare un fatto precedente.

Arancia meccanica dovevo farlo io, nell ’68. Agli

americani era piaciuto molto NEROSUBIANCO

che girai a Londra nel ’66/’67. Così mi invitarono

negli States dove fui accolto in pompa magna alla Paramount.

Ricordo che nella sede della casa di produzione c’era un

corridoio infinito ai cui lati si aprivano le porte dei camerini

e su ogni anta c’era una targhetta: una sfilata incredibile

con i nomi di tutti i vecchi e più famosi protagonisti del

cinema americano, sia attori che registi. Percorrendo questo

lunghissimo corridoio arrivai alla targhetta col mio nome: Tinto

Brass. Ero stato inserito anch’io in quella specie di Olimpo.

Rimasi negli Stati Uniti dieci giorni per valutare un progetto da

realizzare con la Paramount anche se io ero andato in America

avendo già in mente l’idea fissa di fare

L’urlo con Proietti. Non aspettavo altro che

l’occasione per rifilarglielo. Il progetto che loro mi

proposero era quello di realizzare Arancia meccanica. Io

lessi il libro e mi piacque moltissimo, però avevo in mente

Proietti e il mio progetto. Allora dissi ai produttori: sì,

la vostra idea mi piace, accetto di girare Arancia

meccanica, ma prima voglio fare L’urlo. Per

tutta risposta mi hanno detto: vai, cammina, torna in Italia e

così la loro idea l’ha realizzata Kubrick.

Successivamente vidi il suo film e lo trovai davvero belissimo.

Così mi nacque l’idea di utilizzare Malcolm McDowell e

più tardi avviai i contatti con la produzione per ottenere

proprio quell’attore per il mio

Caligola.

|

To answer what you ask me it is necessary to stress a prior fact. I should have

made A Clockwork Orange, in ’68. The Americans really

liked NEROSUBIANCO, which I had filmed in London

in ’66/’67. [Actually ’67/’68. — RS.]

So they invited me to the States where I was received in great

pomp at Paramount. I remember that in the production’s home

office there was an infinite hallway opening to the walls filled with

doors of dressing rooms and on every door was a nameplate: an

incredible parade with the names of every old and famous celebrity

in American cinema, both actors and directors. Traversing this

longest of hallways I came upon the nameplate with my name: Tinto

Brass. I too had been inserted into this Olympian species. I

stayed in the United States for ten days to assess a project to

make a film with Paramount — even though I had come to America

already having in mind the overriding idea to make Howl

with Proietti. I didn’t wait for another occasion to put it

to them. The project that they proposed to me was to film A

Clockwork Orange. I read the book and really liked it;

however, I had in mind Proietti and my project. Then I said to the

producers, Yes, I like your idea; I agree to film A Clockwork

Orange, but first I want to make Howl. Their only

answer to me was: Go, set off, go back to Italy. And so Kubrick

made good on their idea. Ultimately I saw his film and found it

truly beautiful. That’s how I got the idea to use Malcolm

McDowell, and much later I came into contact with producers to

obtain this actor for my Caligula.

|

|

D: Ti sarà

dispiaciuto non aver firmato Arancia meccanica.

|

Q: Are you

disappointed that you hadn’t signed on to do A Clockwork

Orange?

|

|

R: E certo, dopo

sì. Ero ben contento di aver girato L’urlo,

però, indubbiamente, avevo perso un’occasione

importante. D’altro canto io non ho mai ragionato in termini

di carriera; mi andava di fare quello che volevo quando lo volevo.

Agivo d’istinto, forse avventatamente....

|

A: Afterwards,

certainly. I was quite content to have made Howl,

although, undoubtedly, I lost an important opportunity. On the

other hand, I have never thought of things in terms of a career.

I came to work on what I wanted when I wanted. I acted

instinctively, maybe rashly....

|

|

In other alternative universes A Clockwork

Orange was directed circa 1968 by Ken Russell, who took

a serious interest in the project for a while before turning to

Aldous Huxley and The Devils, and/or by another hip

young photographer, David Bailey.

|

|

Like all directors there have been many projects

Ken Russell was lined up for, which did not go ahead. Many did

not go beyond the early planning phase, some stopped after

shooting.

A Clockwork Orange. A package deal

with Russell directing and the Rolling Stones starring. Russell only

heard about the possibility years after.

|

|

...Before starting our journey I learned that

the American director Stanley Kubrick was to make a film

of my A Clockwork Orange. I did not altogether

believe this and I did not much care: there would be no

money in it for me, since the production company that had

originally bought the rights for a few hundred dollars did

not consider that I had a claim to part of their own profit

when they sold those rights to Warner Brothers. That profit

was, of course, considerable.

|

Ibid., pp. 244–245:

|

I knew Kubrick’s work well and admired it.

Paths of Glory, not at that time admissible in France,

was a laconic metaphor of the barbarity of war, with the French

showing more barbarity than the Germans. Dr. Strangelove

was a very acerbic satire on the nuclear destruction we were all

awaiting.... Lolita could not work well, not solely

because James Mason and Sellers were miscast, but because

Kubrick had found no cinematic equivalent to

Nabokov’s literary extravagance. Nabokov’s script,

I knew, had been rejected; all the scripts for A

Clockwork Orange, above all my own, had been rejected

too, and I feared that the cutting to the narrative bone

which harmed the filmed Lolita would turn the filmed

A Clockwork Orange into a complementary

pornograph — the seduction of a minor for the one, for

the other brutal mayhem. The writer’s aim in both books

had been to put language, not sex or violence, into the

foreground; a film, on the other hand, was not made out of

words. What I hoped for, having seen 2001: A Space

Odyssey, was an expert attempt at visual futurism....

I feared the worst: I feared that I would have to work for

the film; film companies give nothing for nothing....

Liana, Deborah Rogers and I went to a Soho viewing room

and, with Kubrick standing at the back, heard Walter

Carlos’s electronic version of Henry Purcell’s

funeral music for Queen Mary and watched the film unroll....

After ten minutes Deborah said she could stand no more and

was leaving; after eleven minutes Liana said the same thing.

I held them both back: however affronted they were by the

highly coloured aggression, they could not be discourteous

to Kubrick. We watched the film to the end, but it was not

the end of the book I had published in London in 1962:

Kubrick had followed the American truncation and finished

with a brilliantly realised fantasy drawn from the ultimate

chapter of the one, penultimate chapter of the other. Alex,

the thug-hero, having been conditioned to hate violence, is

now deconditioned and sees himself wrestling with a naked

girl while a crowd dressed for Ascot discreetly applauds.

Alex’s voice-over gloats: ‘I was cured all

right.’ A vindication of free will had become an

exaltation of the urge to sin. I was worried. The British

version of the book shows Alex growing up and putting

violence by as a childish toy; Kubrick confessed that he

did not know this version: an American, though settled

in England, he had followed the only version that Americans

were permitted to know. I cursed Eric Swenson of

W. W. Norton....

|

|

As far as Kubrick is concerned, I knew

little about him. I was told over the telephone that Stanley

Kubrick wished to make my book A Clockwork Orange

into a film; and I would get no money from it. Well, I said,

I’m not ignorant, I know this already; you needn’t tell me!

But he said: “Would you rather he made it and get no

money, or somebody else make it?” Well, I had a vision

of Ken Russell making it, so I said I was prepared to pay Kubrick

to make the film. It turned out to my surprise that Kubrick didn’t

actually need the money at the time. Kubrick reappeared in my life

or very nearly (he hadn’t really appeared at all, had he?).

He reappeared by name, very nearly, when I was in Australia.

And I was summoned to London to see Kubrick because of two

lines in the book. He wasn’t sure whether it was a copyright or not,

whether they were quotations of an existing song, or whether I had

actually written them. So I rushed from Australia to New Zealand,

to Hawaii, San Francisco, New York, eventually I ended up in

London and appeared for lunch at that old English tavern called

Trader Vick’s. After a couple of old English noggings of

mai-tai, Kubrick did not turn up.

Then Kubrick used the Australian vernacular and

nearly gave birth to a set of diesel engines, when he discovered

that the British edition of the book was different from the

American edition. Indeed, the American edition, if anyone is

interested, has twenty chapters, whereas the British edition has

twenty-one. There’s a cartoon in the British Daily

Express which shows a man and a woman leaving the

cinema, having seen Kubrick’s film, and saying: George,

dear, I do hope they don’t make Son of A Clockwork

Orange. Well, this is no joke because chapter 21, in the

British edition, is precisely that: it’s the account of the

son of A Clockwork Orange, and anybody who wishes

to make this movie as a follow-up is welcome to see me

afterwards.

|

|

Burgess often told the story of how

this final chapter was deleted from the US edition

at the insistence of Norton’s vice-president

Eric Swenson, who felt its hints of a happy

ending — a happiness severely qualified by its

horrendous vision of a cycle of adolescent mayhem

going on and on unstoppably until the end of the

world — amounted to a cop-out. America was

tough enough for the tough ending. Burgess, uneasy

but far too short of cash to object very strenuously,

acquiesced. (It’s only fair to add that Swenson

doesn’t agree with this version of events; as he

recalled in an interview with my droogie David

Thompson, “[Burgess] said ‘You’re

absolutely right’ — I remember those words.

‘Take it out,’ he said. ‘My British

publisher wanted to have the ending so I wrote them one,

but you’re right to take it out....”

|

|

I left for Rome with film money much on my

mind. The men who had originally bought the film rights to

A Clockwork Orange, Max Raab and Si Litvinov, were

prominently featured in the closing credits as joint

executive producers, whatever that meant. It meant probably

little more than that they were entitled to a percentage on

the film’s takings. They would be doing well, if the

queues and the lengthy initial bookings were any indication.

I was doing badly. I had received a single small payment for

the release of my rights and there was no talk of royalties.

A bad contract had been drawn up. It was not long before I

was forced to take Warner Brothers to court at a cost of

several thousand pounds in legal fees. I was eventually

granted a percentage smaller than those of Raab and

Litvinov, to be available when the film was ‘in

profit’. It takes a long time for the films that make

a profit at all — few do — to reach that state. When

my first cheque came, it came naturally through my agent,

who had deducted a ten per cent commission. This was not

balanced by any contribution to my lawyer’s fees. I

began to wonder about the wisdom of having an agent.

|

Ibid., p. 253:

|

Before embarking with Malcolm on a publicity

programme which, since Kubrick went on paring his nails in

Borehamwood, seemed designed to glorify an invisible

divinity, I went to a public showing of A Clockwork

Orange to learn about audience response. The audience

was all young people, and at first I was not allowed in,

being too old, pop. The violence of the action moved them

deeply, especially the blacks, who stood up to shout

‘Right on, man,’ but the theology passed over

their coiffures.

|

Ibid., p. 254:

|

Malcolm McDowell... was still sore from the

physical and psychological pains he had endured while

making A Clockwork Orange. He was terrified of

snakes, but Kubrick had announced one morning: ‘I

gotta snake for you, Malc.’ His ribs were broken in

the scene of humiliation where a professional comedian is

brought on to demonstrate the success of the conditioning:

the comedian had stamped on those ribs too hard. He had

nearly suffocated when, with no cut-away, his head had been

thrust for too long in a water tank. Kubrick was an

imperious director, too imperious even to work with a

script: script after script had been rejected. The filming

sessions were conducted like university seminars, in which

my book was the text. ‘Page 59. How shall we do

it?’ A day of rehearsal, a single take at day’s

end, the typing up of the improvised dialogue, a script

credit for Kubrick.

|

Open-Book Test

(Passing Score: 70%)

1. Who originally optioned or purchased the screen rights — or

at least claimed to have?

a. Terry Southern

b. Andrew Loog Oldham

c. Si Litvinov

d. Si Litvinov and Max Raab

e. Sandy Lieberson

2. Did Paramount Pictures have an interest in the film?

3. How much did Kubrick and Warner Bros. pay for the screen rights?

4. What was Kubrick’s initial response to Terry Southern’s gift of the novel?

5. How familiar was Anthony Burgess with Stanley Kubrick’s works?

6. What was Mick Jagger’s rôle in the negotiations?

7. Contractually, how much, in fees and royalties, was Anthony Burgess entitled to?

8. How much money did Anthony Burgess directly earn from the film?

9. What was Ken Russell’s rôle in a failed production of the film?

10. Was chapter 21 of the novel an addition to or a deletion from the original

work? Which publisher requested the change?

BONUS ESSAY QUESTION (WORTH 20%): How reliable is the written record — any written record?

|