|

IN MARCH 2002 I CONTACTED

ALL THE COPYRIGHT HOLDERS I COULD LOCATE IN ORDER TO OBTAIN

PERMISSIONS. IF YOU OWN THE RIGHTS TO ANY IMAGES OR QUOTES ON THIS

WEB SITE PLEASE CONTACT ME. THANK YOU.

It was in December 2012, after a screening of several of Tinto’s movies, that I heard an incredulous audience member angrily vent out the vehement question,

“So, why do you like Tinto Brass?”

The question was not directed at me, but I nonetheless took it personally, and I took it as a challenge.

In my eyes, Tinto is simply grand.

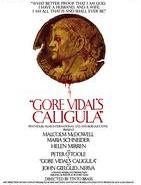

In the US, Tinto is primarily known for Caligula,

which is a pity, as that is by far the worst work in his entire canon.

It has some nice moments, it has some beautiful visuals, but overall it is quite dull and unconvincing,

and it doesn’t help that the film was taken out of his hands and refashioned to become a work of vile sensationalism.

Throughout the rest of the world, Tinto is known for his softcore comedies, which are, more often than not, nice and silly and funny and enjoyable, but fluff.

That is fair enough, but there is something more.

For those of us in the know, Tinto made his mark in the 1960’s and early 1970’s as the master storyteller and stylist.

Not “a master,” but “the master” — yes, I’ll go that far, yes.

I first heard of him, quite by accident, in about February 1979.

Intrigued, I attempted to seek out his movies, but not a single one of his films was available anywhere in the US in any format, on film or on video.

I wrote to every distributor who had previously licensed US rights to any of Tinto’s movies, and nearly every letter was returned, as the businesses had folded.

The few who responded said that no such titles were in their catalogues, and indeed, that they had no records of any such films.

It was also in about early 1979 that video shops began popping up here and there.

All video shops were mom-and-pops back then.

In 1984 one particular pop handed me a long list of titles he had acquired for his brand-new store.

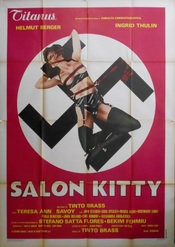

Back at home, I read through the entire list, bored to distraction, and then one title, only one, shouted out at me: “SALON KITTY.”

I phoned Mr Pop right away to ask if that was the movie with Ingrid Thulin, and he said yes.

So I threw on my shoes, dashed to the bus, and rented the movie, heart palpitating.

Alas, it was not so good.

It was a commercial compromise, and the quality of the transfer was so atrocious that it was nearly unviewable.

Despite its numerous flaws and despite its hackneyed story, I had to admit that its technique was astonishing, and some of the ideas were quite good too.

Yes, I was right to be interested. I needed to see some more.

I had to wait until 1988 to see The Key and until 1993 to see a pirated copy of Deadly Sweet.

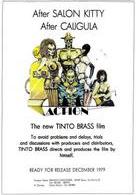

A bootleg of Action popped up on eBay in 1999, and a bootleg of Howl materialized at a local video shop at about the same time.

A year later Whosoever Works Is Lost was shown on Italian television, twice, and Italian acquaintances recorded both instances and sent them to me.

A cropped-and-cut-to-ribbons bootleg of Attraction was made available on the grey market shortly afterwards,

and shortly thereafter I was speechless when I saw that a shop in Italy was advertising an official VHS release of Vacation,

which proved to be one of the loveliest movie fairytales I’d ever seen.

Pirated copies of My Wife appeared simultaneously on eBay and in some Italian shops in Toronto,

and another bootlegger offered The Flying Saucer.

A year or two later a 16mm print of the English dub of The Flying Saucer appeared on eBay.

I managed to acquire that as well — and I became email friends with the gal who had tried to outbid me.

The movies shared something in common, but I had trouble articulating their similarities

and what made them different from everything else.

In a nutshell, Tinto combined two entirely different styles of narrative.

He used the standard storytelling technique, with a plot that one could follow easily

together with characters who captivate us.

In that respect, he followed two of his idols, Charlie Chaplin and Jean Renoir.

So, yes, he used standard framing and cutting and scenery, but that is not all he used.

His influences were also

Alberto Cavalcanti and

Maya Deren and

Bruce Conner and

Fred Mogubgub

and countless other avant-gardists.

It was clear that he also cribbed ideas from architecture and painting and pop art,

all through the anticonformist lens of Wilhelm Reich.

He was able to convey a standard narrative by means of utter abstractions.

He was also able to to make a standard narrative give the impression of being an utter abstraction.

He combined the two outlooks seamlessly, and I found that breathtaking.

I still find it breathtaking.

He also refused to make a distinction between documentary and fantasy, and he blurred those two concepts together as well.

Though he never once in his life had the means to pursue his ideas to their fullest,

though he was always hamstrung by cash limitations and scheduling limitations and contractual limitations

and box-office limitations, he managed to forge a new vision of cinema.

Nobody has followed in his footsteps, and, I fear, nobody ever will.

At the Landmark Loew’s State Theatre during the Syracuse Cinefest in March 2001, I was looking through a display of historical items in the mezzanine,

and concentrated my gaze on a Western Electric Vitaphone projector I had recently seen in operation but which had to be retired once no more replacement parts were available.

Standing next to me I noticed a distinguished grey-haired gentleman whose nametag read

“Radley Metzger.”

So I chatted with him.

I attended the festival because I enjoyed watching silent movies, and asked if he was attending for the same reason.

No, he said, he was there primarily to watch the early talkies.

I asked about Attraction, which he had released in 1969.

He said he thought the movie exceptionally fine, and he was disappointed that it had never found its audience.

He still had a 16mm print in quite good condition, he said, and he would be happy to give me a VHS copy.

I looked for him at the March 2002 Cinefest, but he was nowhere to be found.

He brought his tape along for me at the March 2003 Cinefest,

but, unfortunately, I was in bed recovering from a hospital stay, literally unable to stand for more than a minute or two.

Finally, in the spring of 2004, the VHS arrived through United Parcel Service.

As you can see, these movies were exceedingly difficult to find, requiring incessant searches.

When I watched these blurry VHS tapes and the battered 16mm print, I was simply astonished at what unreeled before my eyes.

Not only were Tinto’s early films entertaining, but they were thought-provoking and brilliantly made — for budgets of close to zero.

He had the strongest sense of cinema of any filmmaker I know of, and he made the most demanding films I’ve ever seen.

However demanding some of his films are, they are nonetheless playful, filled with visual jokes and preposterous humor.

Tinto also had a propensity to experiment with mimicking thought processes,

offering a barrage of flashing images and sounds that should be discordant, but which are actually soothing, as they mesh so well with our thinking patterns.

He would admix naturalism with absurdism, stir both together with comedy, and add lyricism with a frothing of insouciance, to create movies unlike anything else.

What I found especially amusing was his habit of placing actors in actual crowds and shooting with hidden cameras — or, sometimes, with cameras that were not hidden.

The interaction of reality and make-believe I find irresistible.

The bedrock upon which his stories were founded, though, was something different,

something usually unnoticeable until one studies several of his films:

His cherishing of kindness, consideration, caring, and genuine selfless affection (which he defines as true “culture”),

and his disdain for their opposites (which he defines as “civilization”).

Seeing these films, filled as they were with playfulness and brain teasers and compassion, I could not help but be drawn.

There was another ingredient, as well, that shouted out at me:

These films were evidently made by a person who had no love of the status quo

and who had entirely different ideas about who is sane and who is not.

Those who had caring hearts, those who had poetic sensibilities, were those at the bottom of the social ladder; they were “the losers,” as Tinto called them.

Those who lacked these qualities were the bureaucrats at the top.

The stories sympathized with “the losers,” even those “losers” who were so emotionally retarded as to be cruel.

In Tinto’s view, they deserve sympathy as well, for however horrid they may be, they still have the simplicity of infants, and it was not their fault that they could not mature.

That was originally the concept behind Caligula, by the way, an idea that the editors inadvertently obscured in the final film.

This idea is not explicitly hammered home in any of his movies.

It is a subtle undercurrent, barely perceptible, almost subliminal.

These movies were made by someone who had no use for social customs and genuflection to authority figures in a world forever going to war.

“Civilisation,” he explained, “has not learned to live in a cultured way.

It has always avoided looking at certain aspects of human nature, not cultivated dignity as a solid basic passion.”

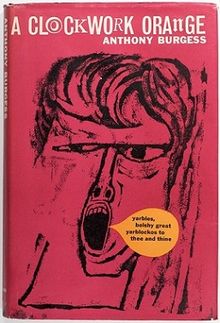

(Shades of Stanley Diamond

and Jerry Mander, yes?)

His political views also imbued all his films.

For reasons that elude me, he has sometimes been derided as a Communist propagandist, but he is not a Communist.

Teen rebellion drew him into the Togliatti orbit, but Roberto Rossellini soon enough talked him out of that.

After a discussion with the master filmmaker, Tinto went home, pulled down all his images of Lenin and Mao and so forth,

and replaced them with pinups, which is much healthier.

He decided that he abhorred all political power structures, whether of the Left or of the Right, which maintain and increase their power only through violence.

I cannot find fault with that viewpoint.

Tinto is opposed to authoritarianism; as a lifelong admirer of Wilhelm Reich, he made his films critical of all authorities and all isms.

His overriding theme, evident in nearly everything he has ever done, is personal and individual freedom above all else.

The logical question now is:

How can a master avant-garde filmmaker be known only for softcore fluff?

The reason commonly supplied is that Tinto’s career must be divided in two.

Tinto himself confirms this, as he happily declares that his career consists of two distinct phases:

The experimental works “Before The Key” and the erotic works “After The Key” —

apparently with The Key resting as the fulcrum between the two phases.

That’s not so helpful.

It would be better to divide his works into three categories:

| ❤ | those from the heart |

| commissions he accepted because he was in no position to turn down a gig |

| movies made primarily for income |

The ones from the ❤ are great.

Most of the ❤ films are challenging, demanding, difficult, provocative, and require multiple viewings.

Some of the  commissions are tons of fun, but some (notably Caligula) are probably worth skipping.

The ones made for commissions are tons of fun, but some (notably Caligula) are probably worth skipping.

The ones made for  vary wildly in quality.

Most of the vary wildly in quality.

Most of the  are softcore works.

The stories are second-rate, if that, though the craftsmanship, performed by the most skilfull technicians, is superlative.

Some people find them offputting, while others seem unable to get enough.

They are not bad, they are sincere, they do have a somewhat sensible message, and some are infectious and even downright hilarious, but they are lightweight.

Regardless of category, these films are all of a piece, and they all bear Tinto’s distinctive personality.

Even if his credit were to be deleted, you would instantly recognize any of these films as Tinto’s.

His techniques and outlook cannot be mistaken for anybody else’s, and nobody has been able successfully to imitate him.

Despite this unity of authorial voice, if you find that you like a are softcore works.

The stories are second-rate, if that, though the craftsmanship, performed by the most skilfull technicians, is superlative.

Some people find them offputting, while others seem unable to get enough.

They are not bad, they are sincere, they do have a somewhat sensible message, and some are infectious and even downright hilarious, but they are lightweight.

Regardless of category, these films are all of a piece, and they all bear Tinto’s distinctive personality.

Even if his credit were to be deleted, you would instantly recognize any of these films as Tinto’s.

His techniques and outlook cannot be mistaken for anybody else’s, and nobody has been able successfully to imitate him.

Despite this unity of authorial voice, if you find that you like a  , you may very well dislike a ❤, and vice versa. , you may very well dislike a ❤, and vice versa.

For 24 years Tinto remained a respected but minor filmmaker who had to struggle to get his dreams on screen.

Why? Because of law enforcement.

His first two feature films were challenged in the courts and initially banned.

By the time they were cleared, they were sent out to cinemas as an afterthought, minus publicity.

The decision by the distributor (Dear Film) and the producer (Zebra Film) to cancel adequate publicity resulted in the films doing nothing more than earning back their minimal costs.

Yet his first two features were better than anything that anyone else was doing at the time.

If only they had been released widely with adequate promotion, if only they had been released on the “art circuit” throughout Europe and the Americas and elsewhere too,

Tinto would have been able to cut his own checks for the rest of his life.

Any serious film viewer would have recognized that these were exceptional works by a young master filled with promise.

Alas, it was not to be.

That is why Tinto found himself accepting several  job offers for mostly low-budget features. job offers for mostly low-budget features.

A young person who grew up with Tinto as a family friend tried to explain something else to me.

In Italy, a filmmaker’s political views determine success.

A Left-leaning Partisan-sympathizing filmmaker will likely get kudos as well as strong support from producers and distributors.

Remember, the Left and the Partisans prevailed in WWII, and Italy enjoyed relatively good relations with the USSR.

Their opponents were utterly loathsome, it is true, but the Left and the Partisans were no angels either, and they had plenty of blood on their hands as well.

The issue, though, is that they won.

For one to be successful, it generally helps to side with the winners.

A filmmaker — say, for instance, Lina Wertmüller or Tinto Brass —

who has a different political view will likely have considerably more difficulty getting films produced, distributed, and publicized.

I am no expert in this matter, but this explanation seems to ring true.

Was it Tinto’s rejection of both Right and Left that hindered his career?

After 24 years of semi-obscurity, the unexpected happened:

In 1983 a studio agreed to produce Tinto’s 1965 script of The Key, and provided a decent budget, too.

The result was a smash hit that outperformed all other films that year in Italy.

With such a success under his belt, Tinto felt certain that he would now be able to dictate his own terms.

He was wrong.

Though The Key was easily the most heartfelt film of Tinto’s career,

though it was intelligent, perceptive, thought-provoking, emotionally complex, and rather difficult,

that is not how audiences saw it, and so that is not how producers saw it.

The Key, you see, contained several minutes of nudity, presented in a natural way, not at all exploitive, and the actors were comfortable performing their scenes.

As Tinto explained, “The Key is a film on sexuality, but not sexy.”

Yet it was the nudity alone that made the movie a sensational international blockbuster.

Producers now saw that Tinto was golden.

His name would guarantee returns, they thought, but only if his name would continue to be associated with T&A.

So Tinto was not able to control his career after all.

He made a concession:

He would make softcore films to please his producers, but he would make them his own, with his own spin and his own style,

and he had the time of his life creating these silly fluffball time-killers.

The silly fluffball time-killers made him rather wealthy, and made him famous too, but they did nothing to help his reputation as an artist.

Tinto insists that his sudden switch from avant-garde to softcore was entirely his own choice, though the evidence suggests otherwise.

It is true, though, that once this choice was made for him, he was so happy with it that it may as well have been his own choice.

He was over the moon to be paid handsomely to film his erotic fantasies,

and there is probably nothing he would have enjoyed more or would rather have been doing than making these silly fluffball time-killers.

True, the films were a job — but they were a job he enjoyed immensely, a job he would not have traded for anything, a job he believed in with all his heart and soul.

Still, though, the films were a job.

A film every year or two would feed his family and pay the rent — and build up a nest egg for his old age and for his heirs.

He knew all too well what it was like not to have a job, and he wanted no repeats of that situation.

So this was his job, and he loved it.

He is fiercely proud of and possessive over these silly fluffball time-killers,

preferring them to the boring, lifeless, insulting run-of-the-mill porn so easily available elsewhere.

He understands that corrupting an audience with pleasure is an honorable task — and a subversive task, too.

After all, corrupting an audience with pleasure was the task of vaudeville, as John Lahr so eloquently put it.

To corrupt audiences with pleasure is to erase social differences, as everyone in the auditorium — poor, rich, upper, lower, dark, light — laughs together.

People who would never notice one another, or who would never dare to introduce themselves to one another, lose themselves in delight while surrounded by people of different strata in society.

To accomplish this effect, Tinto turned for inspiration once again to the semi-brilliant semi-nutjob Wilhelm Reich.

Reich’s ideas of political/social freedom equalling sexual freedom, and political/social repression corresponding with sexual repression,

were put into practical effect by Tinto, who premised his erotic works on this simple concept.

The result was almost miraculous.

One can easily trace a progression here, too.

Each film got sillier, simpler, more simplistic, as Tinto tried to dumb his message down more and more and more, to reach a greater audience, and to have a greater social result.

His final feature, Monamour, was hardly a movie at all; it was almost a tool for use in a marriage-therapy office.

Since Tinto has barely a trace of ego, he took this lesson to heart.

It was not his early works that brought him money and recognition.

It was only the fluff that brought him money and fame, and so it is the fluff that he guards with his life and promotes everywhere.

His early works, regardless of how brilliant they were, failed to attract large audiences, failed to change minds, failed to bring people together.

They caught the attention mostly of intellectuals, who were not the audience he had hoped to reach, as he had no interest in preaching to the choir.

That is why he has let his early works disintegrate.

That is why he makes no effort to revive his early works and has little interest in talking about them.

Yes, if someone wants to license one of his early movies, he won’t object, and he might even put in a good word or two, but that’s it.

That, without question, is a tragedy.

In one sense, his later erotic films are indeed superior to his earlier works.

In the earlier films, the characters were ciphers, two-dimensional, unfathomable.

We never really get to know them, because there is nothing to get to know.

The later films, beginning with The Key, have fully fleshed-out characters.

We can understand these people and possibly even relate to them.

We have certainly met people who are similar.

Tinto probably learned that trick from Rodolfo Sonego (scenarist of The Flying Saucer),

Ennio De Concini (scenarist of Salon Kitty),

and Gore Vidal (scenarist of Caligula),

but even in those three films, the characters are all somewhat alien, distanced, inscrutable.

Nonetheless, the characters in those three films were more than simply ciphers.

Tinto seemed to have enjoyed working with those three writers, at least at first,

and he seems to have taken some pointers from them.

Relatable characters, combined with the sexual content, is what made the later films so massively popular.

Unlike standard erotica,

the later films were no mere parades of sexual antics;

they were well thought out and populated with sympathetic and believable people.

Had Tinto’s earlier films had well-rounded characters,

they may well have attracted more than a mere handful of intellectuals.

Speaking for myself, though, I do not demand well-formed characters;

ciphers are quite satisfying enough, thank you very much.

Another striking difference between the earlier and later films is the attitude towards the machinery.

In the earlier films, Tinto so enjoyed the cameras and the recorders and the editing tables

and the Ciro guillotine splicers

that he found any excuse imaginable to have flashy editing, peculiar camera angles,

speeded motion, colliding sound effects, elliptical narrative, overlays, stream-of-consciousness.

Further, whenever he got an idea that he found amusing, he stuck it in,

even if it ruined the narrative or the sense of the scene.

Beginning with The Key, no more.

The narrative prevailed.

All else was subsumed to the narrative.

Where does Tinto’s heart truly lie?

With the ciphers, or with the characters?

With the playfulness, or with the strict narrative?

He told us, possibly because he didn’t catch himself.

In the commentary track of Cult Epics’ DVD of Howl, by far the wildest and most abstract film of his career,

he admitted that Howl was the film with which he most identified,

that it was his personal favorite of all his works,

the singular work that best represents who he is.

I breathed a long sigh of relief to hear that.

I met Tinto and his wife Tinta for all of three hours at their rented house on an overcast Saturday morning, the third of April 2004.

Upon entering the grounds, I was greeted by a glazed tile embedded in the wall by the kitchen door, which served as the entrance door, which read, simply, “TINTI.”

It was the perfect expression of their marriage.

Tinta, of course, was a nickname.

Her real name was Carla Cipriani, of the famous family of restaurateurs, and she was the warmest person I have ever met.

I’ll always regret that I never got to see her again.

Though I never got to know them, I could pick up on a few things.

First, they were inseparable.

Second, while Tinto was the talent, Tinta was the brains.

I got the distinct impression that it was Tinta who made the deals and negotiated the contracts, leaving the creative duties to her husband.

Perhaps this was not so after all, but I should be surprised were I to be proved wrong.

After The Key, when studio executives would not talk unless Tinto were to propose a work of erotica,

it was Tinta who came to the rescue by writing Miranda.

After getting his feet wet in the new genre, Tinto became comfortable and was able to churn out more and more fantasies.

You see, Tinto had patronized brothels in his youth, with parental approval, and continued to do so even after he married, with wifely approval.

For the life of me I cannot fathom why, and I certainly cannot relate to such a situation at all, but who am I to judge?

It worked for their marriage, and so that’s that.

This surely explains an attitude expressed in some of his movies, in which prostitution is presented as virtuous and joyous —

a view so contrary to my own that, again, I am left baffled, but, again, I don’t judge.

The other side of this equation appears far more strongly, and it is present in nearly all his erotic films,

which are based on the idea that a wife’s occasional one-nighter should not end a romance,

that a husband’s desperately love-sick jealousy can be an aphrodisiac, that a wife’s affair should lead a husband to rediscover her,

and that marriage is the universal panacæa which must be mended, salvaged, renewed, reinforced whenever troubles arise.

What should we read into that?

Am I wrong to suspect an autobiographical basis to these tales?

Was it Tinta who inspired this viewpoint?

After all, she coauthored some of those erotic screenplays.

(For whatever it’s worth, I just ran across this explanation of such an ideology:

Esther Perel, “Why Happy People Cheat,” The Atlantic, October 2017.

All right. I can sort of see Tinta/Tinto’s point.)

Actually, these were Tinto’s stories, but whereas in his own life, he was the one fooling around when wifey was away,

in the movies he switched rôles, and had the women fooling around when their hubbies were away.

My guess (only a guess) is that Tinta realized that, in order to keep Tinto, she had to pay a price,

and the price was simply to let him mess around on the side.

Apparently, for Tinta, the price was low enough and the benefit high enough.

Note that the couples in these stories have no children.

It is as if there were no such possibility.

Further, there is no word for and no concept of divorce.

It is a fantasy world that we see in these stories,

a fantasy world in which nobody has any money worries,

in which plentiful attractive lovers are readily available literally everywhere, in which sex has no physical consequences.

Yes, Caligula had a single utterance of the word “divorce,” a line that was written by Gore Vidal prior to Tinto’s involvement.

Yes, in The Key the couple has a grown child, and in Capriccio the couple has an infant son,

but those plot devices were from the source novels.

Further, I wonder:

Was it Tinta who gently advised Tinto to forget about his best films, put them aside, think of them no more, leave the past in the past,

and concern himself instead with living in the present, making money, and having fun while doing so?

The erotic films, though not works of art, were fabulously successful at the boxoffice.

Tinto would never need to struggle again.

His life was set.

He soon became a cult figure.

His habit of making funny faces and blurting out absurd anecdotes turned him into a pop icon.

Partly related to this viewpoint, take a look at

David Brooks, “The Nuclear Family Was a Mistake,” The Atlantic, March 2020.

Tinto and Tinta loved marriage and detested divorce.

Tinto loved casual sex, loved all manner of pleasures, but found selfish hedonism repulsive.

Tinto and Tinta loved extended family and a wide circle of friends.

Put your thinking caps on.

Every sentient adult realizes that everything is unfair.

There are many unfairnesses in the arts.

Anyone who has worked in the arts has discovered that the business of the arts is no different from the business of drug trafficking.

Both businesses are run by gangsters,

and both are founded upon smear campaigns, planted evidence, smuggling, laundering,

cops on the take, rigged court hearings, grand theft, pervasive viciousness, and worse.

The particular unfairness that concerns us here is recognition.

Recognition is entirely unrelated to quality.

Once a major press offers a scholarly book about a filmmaker, intellectuals begin to take that filmmaker seriously, justly or otherwise.

There were multiple books about Kubrick, Visconti, and Fellini, for instance.

Thus it was that these and some other filmmakers of the 1960’s and 1970’s were embraced by the intellectuals.

Their collected works continue to be revived at museums, complete with program notes.

The screenings are hosted by scholars who give lectures and interview cast and crew on stage before and after each film.

Select VIP’s are invited to after-screening banquets.

Then there are those other filmmakers, every bit as good or even better, who are entirely passed by.

Filmmakers who are not the subject of scholarly books are, by and large, dismissed.

Where is the book about William Sachs, whose première effort,

There Is No 13, is nothing less than brilliant?

The film fell off the map and was seldom shown. It was never released (except briefly in an Italian dub) and it’s almost impossible to find. It was brilliant.

Yet it vanished.

The result was that Sachs gave up and took jobs making drive-in fare — it was a living, and he enjoyed himself.

Yet that first film was marvelous, infinitely superior to its competition, more than worthy of study.

You would be hard pressed to find a single analysis of There Is No 13.

It was not until after his career ended that there was one — only one —

book about Dušan Makavejev,

who is easily one of the most marvelous filmmakers who ever lived.

Where is the book about Guillermo Murray?

Where is the book about Vera Chytilová?

Where is the book about Vasilis Georgiadis?

Will there ever be a book about Jeff Barnaby?

To the best of my knowledge, there are no such books.

Tinto is a bit luckier, as there are several books about him, but they are obscure niche items published by smaller presses, unknown to cineastes, held at few libraries.

The books are not investigative, but consist rather of interviews and plot synopses.

In scholarly books about cinema, even in books focusing on Italian cinema of the 1960’s and 1970’s, there is hardly a reference to Tinto anywhere.

The few that do make a mention of his name do so simply in passing.

The only one that offers praise is Gian Luigi Rondi’s Italian Cinema Today: 1952–1965, which has exactly two sentences about Tinto.

On the other hand, there is an entire industry devoted to churning out endless streams of serious and/or scholarly books about filmmakers I regard as hacks.

Just browse the movie-book shelves of any book shop or library and you’ll see what I mean.

To make my point, let us conduct a thought experiment: Are you itching to see the three films directed by Guillermo Murray?

I have been able to see only one of them, Una vez, un hombre..., which is stunning.

Almost nobody has ever heard of it, though in the early 1980’s it was shown on Spanish-language TV several times as a filler.

Until such a time as there is a scholarly book about Murray, the film will remain buried, unknown, unrecognized, unappreciated.

Nobody will have the slightest curiosity about it.

It’s easily one of the best, one of the most imaginative, one of the most beautiful movies I have ever seen — and yet it is as though it never existed.

This, then, is the situation with Tinto Brass.

If any filmmaker has ever been deserving of serious appraisal, it is Tinto.

Yet he is widely dismissed as merely “the director of Caligula.”

Making matters worse is the unavailability of his better films.

Available copies are generally VHS, blurry, cropped, censored, abridged, as the masters have been locked away for decades.

Some of the masters have even been lost.

There are specialty houses and archives that will present the occasional movie sourced from a VHS, indeed,

but without access to the masters, it is impossible to get screenings at major venues.

That is another reason for the continued obscurity of Tinto’s finest works.

The irony? There is an irony here. Life cannot be lived without irony.

The irony is that on the rare occasions when Tinto’s early works are revived at special screenings, audiences go wild over them.

The audiences are small, only a hundred people at most, usually much less, but the reactions are heartwarming.

The response is half a century too late, but it is better than no response at all.

Chi lavora è perduto (Whosoever Works Is Lost, 1963),

Il disco volante (The Flying Saucer, 1964),

Yankee (1965),

Col cuore in gola (Deadly Sweet, 1967),

Nerosubianco (Attraction, 1968),

La vacanza (Vacation, 1971),

and sometimes even L’urlo (Howl, 1969)

will excite audiences into rounds of loving applause and almost unendurable enthusiasm.

This was not the response half a century ago, sadly.

I wish Tinto could witness these reactions.

Too many people see Tinto as a pornographer.

He is not, not at all.

I see him as a delicate person, a gentle artist,

widely read, thoughtful, with an unusually high intelligence,

who hides his education from others, out of modesty.

I see him as one of those men who is unskilled at independent living,

who was hopelessly dependent upon his late wife Tinta for his day-to-day existence, for his home life,

for his comfort, for his balance, for his sensibility.

I was heartbroken when Tinta passed away, and I was truly worried for him.

Would he be able to survive without her?

Somehow he managed, but his health deteriorated frightfully.

There is a wise warning to us all:

Never meet your idol.

If you do happen to meet your idol, you will be disappointed, or worse.

Chances are, really, that you would be devastated.

I met my idol, and I was extraordinarily lucky, for Tinto did not disappoint me in any way.

I shall never in a thousand lifetimes be able to see certain things from Tinto’s point of view,

but that did not prevent us from getting along.

Though he attempted, at first, to be crusty, he quickly melted and revealed an endearing sweetness.

When we finished our videotaped interview, and as I was crouched on the floor to pack up the camera,

he slid his glasses to the end of his nose and peered over them to look down on me, to remark, in admiration:

“You have a very good knowledge of film culture.”

I answered that I had learned a great deal when I had been a projectionist,

a job he had once had as well, and so we spoke some more.

Of course, it helped that we were both fans of Charlie Chaplin.

He was fond of me, as I was fond of him.

We continued our correspondence for about four years.

He mentioned me to several people, saying that

“he knows more about me than I do!”

Then, tragically, he suffered a cerebral hæmorrhage and lost all memory of me.

I have been unable to reach him since.

I cannot be sure, but it seems that his guardians protect him from my letters,

assuming, probably, that I am naught more than another tiresome fan.

Nothing would please me as much as to speak with him again.

Alas, that will probably never happen.

My website is, in part, a small, humble, skeletal effort to begin to turn the tide.

I first posted this site in March 2002.

Since that time several of Tinto’s better movies have been released on DVD in Italy and in the US.

There have been occasional retrospective screenings of some of his early films both in Italy and in the US,

and even, once, at la Cinémathèque Française.

In 2008 Film International at long last devoted a few pages to Tinto, and so did several other film journals.

Is my site in any way responsible for this new state of affairs?

I should like to think so, but I don’t know.

TABLE OF CONTENTS

APPRENTICESHIP

WINNING ACCOLADES

MAINSTREAM

|

Il disco volante

The Flying Saucer

1964 |

|

La mia signora

My Wife

1964 |

|

Yankee

1966 |

|

Heart in His Mouth

Col cuore in gola

Dead Stop: le coeur aux levres

Deadly Sweet

En cinquième vitesse (In Fifth Speed)

Escalation

Heart Beat

I Am What I Am

Ich Bin Wie Ich Bin: Das Mädchen aus der Carnaby-Street

With Bated Breath

1967 |

AVANT-GARDE, UNDERGROUND,

AND GUERRILLA FILMMAKING

BIG BUDGETS AND BIG HEADACHES

AFTERMATH:

THE LAST GUERRILLA FILM

AND THEN RICHES

EROTICA — THE FIRST PHASE

EROTICA — THE SECOND PHASE

Acknowledgments

I am forever indebted to my

Milanese friend Massimo Polidoro, who will

probably never understand why I like Tinto

Brass’s films, but who has nonetheless

been gracious enough to send me some Italian

VHS releases that are unavailable on this side

of the Atlantic. I am also indebted to Walter

and Carmen of Buffalord in Bettole di Buffalora,

Brescia, who have been kind enough to go far out

of their way to keep me apprised of Tinto Brass

news, to find still more and more

and to tell me about VideoPark in

Genova, which I would probably never have

learned about otherwise. Thanks also to Joyce

Elliott of Conyers, Georgia, for allowing me to

see La mia signora, Jönas

of Sweet

Cozy Video in Sweden for allowing me to

see NEROSUBIANCO, and to others

in England, the Netherlands, Italy, Germany, and

Australia, who sold invaluable items on eBay and

who otherwise rounded up videos and articles for

me. Thanks to their collective efforts, my Tinto

Brass collection has grown from four VHS tapes of

terrible quality to dozens of tapes and DVDs, many

of excellent quality, over just the past year and

a half. Ultimately, I’m grateful to the

blossoming Internet, without which most of the

information and products I’ve gathered would

literally have been unobtainable. And thanks to

Kevin Christopher for taking three hours

out of his schedule to teach me the basics of html

and PhotoShop.

— 2 March 2002

SOURCES: This web site is based upon an enormous number of newspaper and magazine clips,

along with several books, most notably Stefano Iori’s Tinto Brass and Antonio Tentori’s Tinto Brass: Il senso dei sensi,

both of which are available through

Tinto Brass’s official web site.

Another invaluable source is a paperback from 2005 called Obiettivo Brass,

consisting largely of a lengthy interview conducted by Mario Gagliardotto.

The Major Publications

Notes added on 28 April 2007 |

This one will be really exciting, and I await in excited anticipation to receive it:

The never-before-told story of Tinto’s involvement with the London Arts Scene

and the involvement of the London Arts Scene in his British films.

This will also detail some heretofore unknown movie projects that never got off the ground,

including one with Jim Morrison as Christ!

The author is Simon Matthews, who wrote Psychedelic Celluloid: British Pop Music in Film and TV 1965–1974,

a brief and breezy tour.

The forthcoming book promises to be considerably more in-depth. |

Hard to find, but I finally got a copy on Thursday night, 26 April 2007.

Incredibly good info, and it has transcriptions of those wonderful lyrics that I had so much trouble understanding!

Includes the treatments for the unmade movies!!!!!!

Click on the picture above to see the front and back covers, the masthead, title page, and copyright page. |

Not as hard to find, and it still pops up on eBay once in a blue moon.

Click on the picture above to see the front and back covers, the masthead, title page, and copyright page. |

Still pops up on eBay.

Click on the picture above to see the front and back covers, the masthead, title page, and copyright page. |

Oh this one is sweet.

It consists largely of affectionate tributes to Tinto Brass from those who have known him and worked with him.

Click on the picture above to see the front and back covers, the masthead, title page, and copyright page. |

Apparently Nocturno is regularly shipped to subscribers in a plastic wrapper that includes a separately bound supplement entitled Nocturno Dossier.

This particular Dossier was devoted entirely to Tinto Brass, and it includes information and photos you won’t find anywhere else.

Click on the picture above to order a copy. |

The most recent book, which apparently borrowed a bit from my web site.

(But then, hey, my web site borrowed from some of the books I’m advertising here.)

Click on the picture above to see the front and back covers, the masthead, title page, and copyright page.

NOTA BENE: The original edition is beautiful, with glossy paper and marvelous illustrations.

Apparently, there is a pirated edition making the rounds, on rough paper with degraded illustrations.

Make sure to get the one with glossy paper!

|

| Now, how do you get hold of these publications?

Well, except for the Nocturno Dossier # 25

it will be a bit tricky to get these items.

Keep trying Tinto Brass’s web site,

as well as the Internet Bookshop,

Hoepli,

and BookFinder.

Good luck! |

Giovanni Brass was born in Milano

on Sunday, 26 March 1933, but was raised in Venice.

His grandfather, painter Italico Brass,

gave the youngster the nickname of Tintoretto,

which was itself the nickname of painter

Jacopo Robusti (1518–1594).

(Incidentally, Gore Vidal, in a TV special called

Artful Journeys: Vidal in Venice, referred to Tintoretto as the Cecil B. De Mille of Venetian painters.)

Tintoretto was soon shortened to Tinto.

Tinto’s father Alessandro was a noted and well-to-do attorney,

and Brass originally planned to pursue that same career.

He completed his university law degree

but then moved to Paris in 1957 and got a job as a projectionist for

the Cinémathèque Française, where he also apprenticed

to film archivist/curator Henri Langlois through 1960.

Family tree:

Italico

Felice

Luciano

Brass (b. 14 December 1870, Gorizia; d. 16 August 1943, Venice)

married

Lina Rebecca “Nina” Vigdoff, originally of Odessa.

Children: Italico and Alessandro.

Alessandro Brass (b. 20 January 1898, Venice; d. 1968) served as Vicepodestà of Venice.

He married

Carla Épouse Curletti (b. circa 1910, Milano; d. 2007, Venice, at age 97).

Children of Alessandro and Carla: Italico, Giovanni “Tinto,” Maurizio “Malo,” Andrea.

Tinto (b. 26 March 1933) married Carla “Tinta” Cipriani

(b. 30 March 1930, Verona, d. 9 August 2006, Merano),

of the famous Cipriani family of restaurateurs.

Tinta’s father was Giuseppe, who established the six-room Locanda Cipriani on the Island of Torcello in the 1930s,

frequented by Churchill, Chaplin, Chagall(!), and countless others.

It was during a stay here that Hemingway penned Across the River and into the Trees.

Tinta’s brother was Arrigo, who ran Harry’s Bar in Venice, which was made famous by Hemingway.

Tinto and Tinta later came to operate the Locanda Cipriani, though for how long I do not know.

They were certainly in charge in 1991.

Tinto and Tinta’s children: Beatrice (b. 1960) and Bonifacio (b. 1963).

A colleague in the UK just forwarded me a little information about Tinto’s brother Maurizio.

This comes from a 1983 book called L’immagine e il mito di Venezia nel cinema:

“Born in Milano on 27 August 1941 (a Venetian and Tinto’s brother) — Actor and documentarian.

Actor and assistant for Rossellini (Acts of the Apostles). Made shorts at the Beaubourg in Paris

and was, more recently, active in the writing of dubbing dialogue for foreign films.”

Just after sending me this, the same colleague informed me that Malo had recently passed away,

and he sent me a link to

Claudio Bondì’s tribute:

“Malo (Maurizio) Brass, brother of the more famous Tinto, has died.

We were friends; similar sentiments bound us together:

an affection for Rossellini (for whom Malo was assistant and actor in Acts of the Apostles),

the countryside we chose to live in (Trevignano Romano),

the love of Venice, of which he was a citizen and I a sometime resident.

Years ago when we got to know each other at the

Hermes bar,

I asked him why he had chosen this landscape.

He responded: ‘How can a Venetian not live by the water?’

Malo was a cultured, educated man, of old-fashioned elegance, who spoke French perfectly.

When he would meet my wife Laura on the street, he, taking off his hat, would begin to ‘chat’ in Venetian.

It was amusing to hear them chatter in their own language, or sometimes in French, in Alto Lazio.

His slender figure stood out in the care with which he selected a booklet in the Sunday market stall,

or even a walking stick, a bow tie.

Things were always a bit out of date, but tasteful.

The two of us discussed cinema, literature.

In a kindly way, he presented my collection of poems to the Palma cinema.

He wrote and read a learned introduction which he then gave me and which I keep.

With Malo went also an eyewitness of

Roberto Rossellini’s television “of conscience,”

which, however you wish to consider it,

today seems to come from a utopian and inimitable “elsewhere.”

Dear Malo, I’ll miss you. May the earth rest lightly upon you.”

Any further information is most welcome!

|