The Missing Scenes in

|

|

Once upon a time, I began writing about this movie,

but I gave up once the resources ran out.

Now that more materials are available, perhaps I should start over again.

|

|

Problematic movie.

Totally different from anything else Buster ever did.

The irony that kept his stories afloat is here entirely missing.

The resourcefulness is pretty much gone.

Instead we have a gentle story about a street-fighting bully who has gone straight,

leading an unassuming life as a photographer with his 1912 Errtee Button Tintype Camera.

This was a profession that had been nearly obsolete for decades.

He has no aspirations for anything other than quiet invisibility in a small room in a cheap boarding house all by himself.

He is socially awkward to the nth degree, painfully shy and

|

|

Problematic? Why do I say problematic?

Because there is a problem:

More than three minutes are missing from the beginning of Reel 3.

Buster leaves an empty Yankee Stadium in NYC,

then, with his dilapidated

|

|

What are we missing?

Buster’s own recollection was quite exact.

George C. Pratt of the George Eastman House in Rochester, NY, interviewed Buster in 1958.

His interview was not published until 16 years later, in

Image magazine, vol. 17 no. 4 (1974), pp. 19–29.

It was reprinted in Kevin W. Sweeney, ed., Buster Keaton Interviews (Jackson: University Press of Mississippi, 2007),

pp. 32–47.

We are fortunate that we have the actual recorded interview, unedited, here:

|

_by_Georg.jpg) https://soundcloud.com/george-eastman-museum/interview-with-buster-keaton If this ever disappears (other copies have disappeared), download it. |

|

Here is the relevant section:

|

|

PRATT: There’s one unfortunate gap in our print. Apparently the negative

had deteriorated. It’s the part where you go out for the first day and everything

goes wrong. There’s just a little bit of that left.

KEATON: That’s a shame because some of the biggest gags are there.

PRATT: Tell me about what was in there.

KEATON: Well, the number one was I think I saw a lot of people around a

Park Avenue hotel and I got there and they say, “It’s the admiral that’s

coming out!” So I busted through the crowd and I photographed the

admiral going right from the main door into his limousine. Only the

mistake I made was I photographed the doorman. That was my first

error. Then I got over to the Hudson River and got a shot of a battleship,

and then a parade on Fifth Avenue, and I double-exposed it by

accident. So I had the battleship comin’ down Fifth Avenue and the

parade comin’ down the Hudson River. I went to a launching of some

millionaire’s new yacht, one of the Vanderbilts, and I made a mistake

and set my camera up on part of the cradle that launched the boat. So

I was launched with the boat. In a finish I photographed a disappearing

gun — one of those great big things that they had come up and shoot.

While I’m photographing one, I didn’t know if, but I was right up

against another one that nearly took the seat of my pants off.

|

|

Now, shall we take a look at the relevant pages of the cutting continuity?

Any text in bold is missing from the current editions of The Cameraman.

We see that the first three+ minutes of Reel 3 have vanished.

|

|

Because the notations have confused too many people, we should work our way through this.

|

| • |

The scenes are not numbered.

Instead, every edit is numbered.

Whenever one piece of negative is physically joined to another piece of negative,

that counts for the next number, and each reel starts over again at 1.

Though the scenes are not numbered, the colloquial studio lingo would refer to “Scene 103”

and “Title 104,” even though the meaning was “Edit number 103”

and “Edit number 104.”

It was a spoken shorthand that confuses us all nowadays.

|

| • |

“S” means that the footage in question is part of a Scene.

|

| • |

“T” means that the footage in question is a Title.

|

| • |

“B&W” means only that the negative stock was black and white;

it does NOT mean that the film as shown in cinemas was in black and white.

The film as shown in cinemas was, of course, tinted, possibly toned as well.

Most likely, day scenes were sepia and night scenes were blue.

|

| • |

Each reel opened and closed with an identifier: “Part One,”

“End Part One,” “Part Two,” “End Part Two,”

“Part Three,” and so forth.

As a general rule, these were not shown on screen.

Up to 1923, yes, they were shown on screen,

but then various other practices were adopted to enable projectionists to skip over those titles.

We see the method used for this film, and used also for other MGM productions of the time.

As soon as the projectionist saw “The Admiral is coming out!” on screen,

he (almost always he) would start the motor of the next projector,

and when he could hear that it was up to speed, he would slide a metal plate over to block the lens of the old projector

and unblock the lens of the new projector.

The new projector would then show the next second or two of “The Admiral is coming out!” on screen.

The transition from one reel to the next was thus nearly seamless.

|

| • |

The footage counts are NOT exact.

There are sixteen frames to each foot of film, but the footage counts here were all rounded to the nearest foot.

Films in 1928 were usually projected at 1½ feet per second (24 frames per second),

and so that can give you a good idea about the running time of each shot.

|

|

So, with that knowledge under your belt, you are ready at long last to bear witness

to the missing three+ minutes of the beginning of Reel 3.

|

| NO. |

SCENE |

COLOR |

FEET |

DESCRIPTION |

Reel 2 Page 6 |

| 93 |

S |

B&W |

8 |

FULL FIG SHOT Buster acting as pitcher. |

|

| 94 |

22 |

FULL FIG.SHOT Buster acting as pitcher. |

|||

| 95 |

6 |

LS Diamond - Buster in pitcher mound - still pantomiming. |

|||

| 96 |

9 |

MCS Buster in pitcher's mound,

doing pantomime |

|||

| 97 |

22 |

MLS Buster in home plate,

doing pantomime business. |

|||

| 98 |

21 |

MCS Buster at home plate

doing pantomime of batter. |

|||

| 99 |

2 |

LS of grandstand center field. |

|||

| 100 |

23 |

MCS Buster at home plate -

still doing batter pantomime. |

|||

| 101 |

82 |

LS Buster at home plate he hits ball and pantomimes -

makes home run - does slide finishes takes bow, sees ground keeper -

turns goes gets his camera - starts to walk off field FADE OUT |

|||

| 102 |

12 |

FADE IN EXTREME

LS exclusive hotel, street, Buster crosses over to hotel. |

|||

| 103 |

8 |

THREE FOURTH FIG.SHOT of group at doorway -

Buster edges into crowd - man speaks title: |

|||

| 104 |

T |

20 |

"The Admiral is coming out!" |

||

| 105 |

T |

3 |

END PART TWO |

||

| Reel 2 Page 6 |

|||||

| NO. |

SCENE |

COLOR |

FEET |

DESCRIPTION |

REEL 3 PAGE 1 |

| 1 |

T |

B&W |

3 |

REEL THREE |

|

| 2 |

T |

16 |

"The Admiral is coming out!" |

||

| 3 |

S |

6 |

MS of Buster with camera trying

to break thru crowd in front of hotel lobby. He pushes his way thru crowd. |

||

| 4 |

42 |

MS exterior of hotel lobby.

Buster comes into foreground, sets up his camera, crowd of people in the background.

Doorman comes out first. Admiral and his staff follows the doorman.

Buster comes into scene with his camera he is taking a moving picture of the doorman;

Camera Pans as Admiral and his staff get into automobile at curbing.

Buster is grinding his camera and taking pictures of doorman

as he opens and closes the door for Admiral and his staff, getting into car.

Buster realizes his mistake, picks up his camera, walks off scene,

turns and looks around and FADE OUT |

|||

| 5 |

24 |

FADE IN on yacht in dry dock.

People in foreground. Girl standing by bow of boat with a bottle in her hand.

Buster comes into scene with his camera,

sits his camera up in front of boat, and starts to take picture of girl

hitting the bow of the boat with bottle.

He is grinding the camera, and the boat slides into water.

Buster and camera are standing on a plank as boat slides into water. |

|||

| 6 |

18 |

CU of boat sliding into water.

Buster standing on plank with camera as boat slides into water.

Boat, Buster and camera slide into the water, and FADE OUT |

|||

| 7 |

7 |

FADE IN

MS of large cannon. |

|||

| 8 |

4 |

CU of cannon firing

and recurls back into position. |

|||

| 9 |

27 |

MS of Buster coming into scene, carrying his camera.

He sets his camera on top of concrete walk as large cannon comes into scene and fires a shot.

FADE OUT |

|||

| 10 |

10 |

FADE IN MS. of office of M. G. M. news reel.

Buster comes thru doorway carrying his camera. |

|||

| REEL 3 PAGE 1 |

|||||

| NO. |

SCENE |

COLOR |

FOOT |

DESCRIPTION |

REEL 3 PAGE 2 |

| 11 |

S |

B&W |

13 |

LS Interior of office.

Sally is sitting at desk. She looks at Buster as he comes into office.

Buster sets his camera up against railing in office and starts

to take out negative from camera. |

|

| 12 |

2 |

MS Editor and two girls at desk.

Editor is looking off scene. |

|||

| 13 |

5 |

MSU Sally sitting at desk.

Buster and his camera at railing. He talks to Sally and shows her the negative in box. |

|||

| 14 |

3 |

MS of Editor and two girls sitting at desk.

Editor is looking off scene. |

|||

| 15 |

3 |

MCU Buster and Sally looking off scene.

Sally turns to Buster. Buster walks toward camera, and thru gate. |

|||

| 16 |

3 |

MS of office.

Editor walks into scene and meets Buster. Buster speaks title: |

|||

| 17 |

T |

8 |

"It's great stuff, sir! I hope you'll look at it!" |

||

| 18 |

S |

11 |

MCU of Editor and Buster.

Buster is handing Editor box of negative.

Editor turns and hands to someone off scene, turns and speaks title to Buster: |

||

| 19 |

T |

7 |

"Come around tomorrow and we'll have it ready to project." |

||

| 20 |

S |

5 |

MCU of Buster and the Editor.

Editor turns and walks off scene. Buster also turns and starts to exit from scene. |

||

| 21 |

2 |

MS of Buster in foreground.

He walks to background and starts to talk to Sally. |

|||

| 22 |

20 |

LS of office.

Buster is talking to Sally in background.

Stagg comes into scene thru door carrying his camera.

He hits Buster with door, comes to foreground of scene and goes thru gate.

Door closes as another cameraman starts to come to doorway and legs of tripod go thru glass in doorway.

Buster turns and looks as man comes into scene.

Editor comes running into scene and starts to talk to man about breaking glass in door.

Buster is talking to Sally in background. |

|||

| REEL 3 PAGE 2 |

|||||

| NO. |

SCENE |

COLOR |

FOOT |

DESCRIPTION |

REEL 3 PAGE 3 |

| 23 |

S |

B&W |

6 |

MCU of Buster and Sally

talking to one another and looking off scene. They are laughing and FADE OUT |

|

| 24 |

26 |

FADE IN LS of projecting room.

Stagg comes into scene and is talking to another cameraman

as Editor and Sally comes into scene and take seats in projecting room.

Editor is talking to Sally - Stagg is walking around. |

|||

| 25 |

18 |

MS Reverse angle of projecton room.

Sally is at desk talking to Editor.

Buster comes to foreground and sits in the front row.

Editor turns to man in projection room and tells him to start.

Scene goes dark as everybody starts to look toward screen

as picture is about to be projected. |

|||

| 26 |

7 |

CU of projection room.

People in foreground.

Picture on screen in background, just showing the legs and body of people walking. |

|||

| 27 |

3 |

MCU of Sally and Editor as they look at picture.

Editor is very mad. Sally is down-hearted. |

|||

| 28 |

6 |

MS of men on horses in a jumping meet.

Buster cranks camera and makes horses jump backward. |

|||

| 29 |

5 |

MCU of Buster sitting in projection room

looking very sad at what he sees. |

|||

| 30 |

8 |

MS of a man on spring board making a fancy dive.

He hits the water and springs back onto spring board. |

|||

| 31 |

5 |

MS of projection room,

Buster sitting in a chair in foreground. |

|||

| 32 |

3 |

CU Sally sitting by desk in projection room.

She bows her head. |

|||

| 33 |

3 |

CU of Buster sitting in projection room. |

|||

| 34 |

12 |

MS of buildings and battleship in foreground.

Warriors and automobiles. |

|||

| 35 |

4 |

MS of Buster sitting in projection room. |

|||

| 36 |

5 |

MS of people running

in all directions on street. |

|||

| REEL 3 PAGE 3 |

|||||

|

Richard Warner told me to take a look at a 1950 movie called Watch the Birdie,

in which Red Skelton

|

|

|

|

What, pray tell, is a disappearing gun?

Do you know?

I didn’t know.

YouTube to the rescue:

|

Click on the image to see the video. 3dfort, British 6-inch BL-gun MkVI on Mark IV disappearing carriage H.P., uploaded on Oct 21, 2022 |

|

By the by, I’m curious.

Back when I was about 19 or so, I was paging through an ancient projection manual,

and among the myriad makes and models it detailed

was a dual-projector outfit that required the operator to remain between the two machines at all times.

Projector 1 had a normal configuration, but Projector 2 was a mirror image.

There was only a single viewing port for the operator, between the two machines.

The bases for the two projectors were interconnected and linked with belts.

I do not remember what that book was.

I do not remember when it was published or by whom.

I do not remember the make or model of that

|

|

So, it’s time to wonder when the full-length film was last seen.

It popped up for one day,

Wednesday, 22 May 1935, as second on a double bill with a Fox film at the

Electric Theatre in Curtis, Nebraska.

Did the Electric still have a musician it could bring in to accompany the film?

I am willing to bet one dollar that the Electric cropped the image with the Academy aperture.

It popped up again for two days,

Tuesday and Wednesday, 26 & 27 May 1936,

as the second on a double bill to a different Fox film at the

Missouri in Maryville, Missouri.

My same question and supposition apply.

Next question: Why did The Cameraman get those two bookings?

It was not because the cinema programmers chose the film or even wanted it.

It was surely because it was the only affordable film available from the exchange at the time.

You know how that conversation goes.

“We need a second picture to fill out the bill. Whaddaya got available?”

“Everything is shipped out right now, but we do still have a print of The Cameraman.

We can get it to you for 20 bucks.”

“We’ll take it.”

My guess is that Curtis and Maryville were both on the

Kansas City exchange.

I wonder what ever happened to that print.

Were there other bookings in the 1930’s, 1940’s, 1950’s?

I do not know, except for one that I am certain about, in 1959,

and we shall get to that shortly.

|

|

What else do we know?

We know that it was sometime in the 1940’s that Karl Malkames did some work for the George Eastman House.

Karl Malkames, like his father Don, worked in the movies as a cameraman.

He was a collector and archivist as well.

Rather than accept a cash payment for his work,

Malkames requested a print of The Cameraman, a film for which he had a particular fondness.

It was years before it arrived.

What took so long?

My best guess is that the George Eastman House simply did not have any access to material on The Cameraman.

|

|

We learn something from an unsigned June 2019 article posted by Il Cinema Ritrovato,

“The Restoration of The Cameraman.”

The article on a first reading seems simple and straightforward.

Then we think about it for a moment or two and then

|

|

Thus it was that in 1951, Karl Malkames at long last received his long-awaited print of The Cameraman,

and, to his disappointment, it was 16mm rather than 35mm.

Also, it was missing the the last 13 seconds of Reel 2 (the Beverly Wilshire) and the beginning of Reel 3.

Strangely, it was also missing a title, “The Big Sea Lion!”

The chronology begins to make sense.

|

|

What else do we know?

We have a passage from Rudi Blesh’s Keaton (NY: Macmillan, 1966), p. 302:

|

|

In 1953, when a friend of Buster Keaton asked to see it projected,

he was told a surprising thing. “The present print is worn out,” an

executive said. “It”s been our training picture. Ever since 1928 we’ve

made each new comedian study it. From Durante to Abbott and

Costello, from Mickey Rooney to Red Skelton and the Marx

Brothers.”

The MGM man spoke with evident pride. But it is equally evident

that he was not thinking of Buster Keaton, a man whom MGM had

already long since forgotten. He was thinking, MGM story, MGM

direction, MGM production.

|

|

Who was the friend who requested a screening?

I am certain it was Rudi Blesh himself.

I mean, who else would it have been?

Who else could it have been?

Who was the executive who explained that there was nothing at present to screen?

That is a mystery that may never be answered.

|

|

Too many people have misunderstood the above quotation from the MGM executive.

He did NOT say that the ONLY copy was worn out, but that the PRESENT copy was worn out.

The PRESENT copy was not the original; it was printed from the camera negative.

The executive did not even imply that there was a problem with the negative.

As a matter of fact, by mentioning that the PRESENT print was worn out,

he was implying that there would later be a REPLACEMENT print.

|

|

Was it really the training picture, though?

If this truly were the training picture, then it should but won’t come as a surprise

that Buster was not permitted to follow his own template,

and that he was not permitted to instruct others.

The instructions he was told to obey were to do exactly the opposite of what he had done in The Cameraman.

If this truly were the training picture,

then it is curious that no other MGM film would ever have such a gracefully simple story —

no MGM movie that I know of, anyway.

Boy Wonder Thalberg had the idea that to keep the audience involved

required a complicated narrative consisting of threats from gangsters who frame the innocents

and then there are more gangsters and then cops and robbers and more cops

and more gangsters and gun battles and the good guys outwitting the bad guys

but that their heroic actions cause the cops to see them as the bad guys

which affords the gangsters an opportunity to move in on them and frame them up again

and then get pursued by yet more gangsters and on and on and on and on and on and on and on and on

and oh my gawd is it so awful and at the end

the boy and the girl discover that they love one another and they live happily ever after.

No MGM staff writer took The Cameraman seriously.

Some people argue that the crowded stateroom in A Night at the Opera owed its inspiration to The Cameraman.

Maybe. I’m not convinced.

As we saw above, MGM remade some scenes from The Cameraman for a Red Skelton vehicle called Watch the Birdie,

and they were quite precise, right down to the camera angles.

Then came one of the rare MGM movies I actually like,

and Ben Model was struck by something striking that had never struck me. Behold:

|

|

Click on the image to see the video. Ben Model - silent film accompanist/historian, Buster Keaton and Gene Kelly in parallel scenes If YouTube ever disappears this video, download it. |

|

We can parse the executive’s words further.

From what he said, we can infer that the PRESENT print had been made in 1928

and had been used as training through sometime before 1953, probably sometime in 1947.

It had probably been projected a hundred times or so through the years.

That print was full-aperture silent on nitrate base.

Nitrate stock, in case you don’t know, is far from resilient,

and many nitrate prints had B&H sprocket holes rather than Academy sprocket holes,

and B&H sprocket holes are prone to tearing.

Worse, the sprocket teeth in projectors in those days were large and sharp and extremely harsh on film.

After 20+ years, it was hardly surprising that the print would be worn out.

It had surely shrunken, since all nitrate film shrinks rapidly and continues to shrink.

It becomes extremely brittle with age.

The sprocket holes had probably all popped with repeated projections.

Yes, I am quite sure it was a goner, and it was surely sent to reclamation.

Come 1953, the film could not be shown again until it was reprinted.

That’s what the unidentified executive meant.

|

|

But the film was not reprinted.

Why?

One reason, undoubtedly, was that the divorcement decree of 1948,

United States v. Paramount Pictures, Inc., 334 U.S. 131 (3 May 1948),

changed the movie business forever.

There were no further staff comics, and hence there was nobody to train.

There was no point in making a new print.

The other reason, of course, was that there was not enough left to reprint!

Clearly, the MGM executive was not aware that making a replacement print would prove to be a challenge.

|

|

Once upon a time, long long ago,

Jack Dragga sent me copies of some fascinating documents.

What on earth did I ever do with them?

I can’t find them, but I do find quotes I had culled from them.

So, with apologies for not being able to show you the originals,

here are the quotes I found so fascinating.

|

|

On 5 December 1957, MGM lab

technician Henry Siccardi wrote an interoffice memo to his superior, Merle

Chamberlin, entitled “Report on the Condition of the Buster Keaton Pictures.”

The conclusions were distressing. The negative of The Navigator (1924) had

completely deteriorated. The negative of Seven Chances (1925) was badly

shrunken, and any attempt to rescue this film “would be hazardous due to the

shrinkage being a little over the .093 safety factor.” The original camera negative

of Battling Butler (1926) was unprintable, and the first reel was missing. The

camera negative of Spite Marriage (1929) was unprintable. Finally, as for The

Cameraman, “Reel 1 is missing... original negative is unprintable as it has many

torn perforations, is excessively shrunken, also in the following reels, scenes have

deteriorated: Reel 3, Scenes 60 and 61; Reel 4, Scenes 43 and 44; Reel 6, Scene 65

and the last 150 feet; Reel 6, Scenes 33, 34 and 35.” Siccardi explained what he

meant by “deteriorated”: “said material has decomposed and there is no image

or picture in these decomposed sections.” Significantly, Siccardi made no

mention of any problems with Reel 3 “Scenes” 1 through 29, which constitute the

only segment that has yet to be recovered.

Apparently, the beginning of Reel 3 was still there!

Neither did Siccardi make any mention of

the end of Reel 2, which has not been issued in a good copy since the 1930’s.

Why on earth was Reel 1 missing?

The George Eastman House printed Reel 1 in 1951.

How could it have vanished less than seven years later?

|

|

My best guess is that Kodak’s report of February 1951 and Siccardi’s report of December 1957

concerned two different negatives.

Each was missing segments that were included in the other.

One had been sent to Rochester for reprinting and preservation in 1951,

and a different camera negative was on Siccardi’s inspection bench in 1957.

If my guess is correct, then the people involved seemed not to realize

that they were dealing with two negatives,

one shot for domestic use and one shot for export.

|

|

We notice that though the lab reported that the camera negative was unprintable,

the lab made no mention of lavenders/fine-grains or copy negatives or prints.

|

|

From the above, we can safely infer that at the beginning of December 1957,

MGM wished to reprint The Cameraman but learned that it would not be possible to do so.

|

|

Il Cinema Ritrovato also tells us about

“a 35mm MGM second-generation fine grain manufactured

by MGM labs in 1957 from the 35mm original camera negative.”

Oh good grief! That doesn’t make any sense either!

You can’t make a “second-generation fine-grain”

from a “35mm original camera negative.”

Impossible.

A piece of the narrative is missing.

|

|

Here is my best guess, pending further information:

Since the George Eastman House surely had a fine-grain,

MGM borrowed it to make a new copy negative.

MGM then used that copy negative to make a second-generation fine-grain.

Even more likely, this was not a second-generation fine-grain.

It could have been the one that MGM had deposited at Eastman.

|

|

If my guesswork is correct, then we can piece together the story of the original lavenders

and the 1928 copy negatives and any earlier prints:

They had all vanished.

Perhaps they had turned to dust.

Perhaps the emulsion had melted off during the hot summer of 1937.

Perhaps by some wild coincidence they had all gone up in smoke.

MGM had a vault fire in 1955, but would all those elements have been kept together in the same vault?

That seems borderline unbelievable.

I don’t know what happened. Does anybody know?

|

|

On 4 April 1958 Merle Chamberlin issued an interoffice memo to Henry Siccardi to

“send whatever negative material we have on THE CAMERAMAN via Emery Air to:

Mr. Herb Gelbspan, Hal Roach Studios.” This is a mysterious memo. Why would

MGM send these materials to Roach? Further, there seems to be no indication

that these materials were ever returned.

|

|

We know that the George Eastman House in Rochester, NY,

had a print that was missing the first three+ minutes of Reel 3.

Joe Franklin, in Classics of the Silent Screen (NY: Bramhall House, 2 November 1959), p. 186,

seemed to imply that MoMA had an exact copy of what GEH had, but it is difficult to ascertain that.

|

|

What else do we know?

We know that Rudi Blesh completed the typescript of his Buster bio sometime in 1958,

but that the publisher rejected it for being too long.

Rudi refused to abridge it and so the book went on hold.

It was not until 1965 that Rudi finally gave in and, rather than abridge the book,

he simply chopped out all but the beginning.

As for Buster’s life from the 1930’s through the 1960’s,

he wrote a summary of some 30 pages.

On the final two pages of his book is a passage that has puzzled me since I first read it in 1975,

and it puzzles me to this day.

Shall we take a look?

|

|

...Rohauer began collecting and restoring

prints of Keaton’s own films wherever they might be found,

here and in Europe. He set up a corporation for Buster and then,

through all possible means — locating old contracts, purchasing rights,

buying off claimants of all shades of legitimacy, using persuasion and

even litigation — Rohauer began to give the corporation assets, power,

and meaning. It is a full turn, indeed, of the Hollywood wheel:

Keaton, the nonorganization man, is now the center of an organization

framed not to exploit but to restore his rights.

Along the way others joined the effort: Leopold Friedman, formerly

with Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer, and in France, a famous disciple

of Keaton’s art, Jacques Tati. The long single-minded effort is now

near completion. The corporation now owns all of Keaton’s work,

beginning with The Butcher Boy of 1917 made with Roscoe Arbuckle,

through all of Buster’s own silent two-reelers and features

from 1920 to 1928, on to the cream of his MGM work from 1928

to 1933, and even including all of his Educational Comedies from

1935 to 1937....

|

|

That’s a head-scratcher.

Rohauer never owned MGM’s Buster movies.

John Baxter, in “The Silent Empire of Raymond Rohauer,”

The Sunday Times Magazine, 19 January 1975, p. 33, offers a hint:

|

|

Rohauer also began a campaign

against MGM to relinquish Keaton’s

later works on the grounds, admittedly

sound, they they were not

being effectively distributed.

|

|

Then we run into this mind-boggling statement from Steve Massa, posted on

“Missing Reel on Buster Keaton’s ‘The Cameraman,’”

NitrateVille,

Thursday, 24 November 2011:

|

|

Despite the fact that around 1985 Raymond Rohauer personally told me that he had the footage squirreled

away (I think he really loved keeping people guessing) it isn’t known to exist. Brownlow and Gill couldn’t

find it anywhere.

|

|

What do we make of the above?

I can think of a way to harmonize all three of those statements,

though, admittedly, this is just guesswork.

Rohauer simply lied to Blesh, falsely claiming that he had acquired the rights to Buster’s MGM movies.

In fact, he had made a case for his ownership, but MGM wouldn’t give him the time of day.

To Steve Massa, Rohauer told the truth.

Yes, he probably did once have a nitrate print of The Cameraman

but did not yet realize that it had crumbled to dust in the years since.

But I could be wrong.

Note what happened next, in November 1959:

|

|

We know that in November 1959, the British Film Institute’s National Film Theatre in London

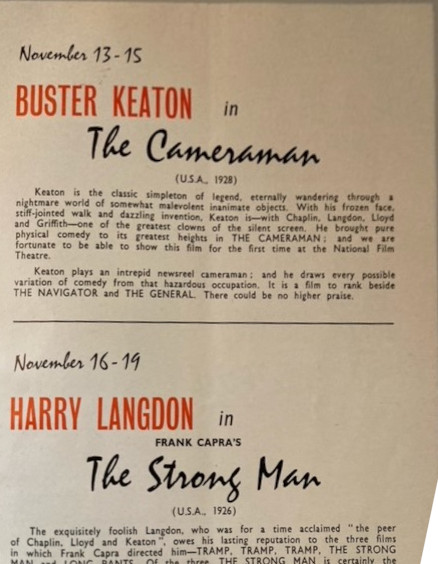

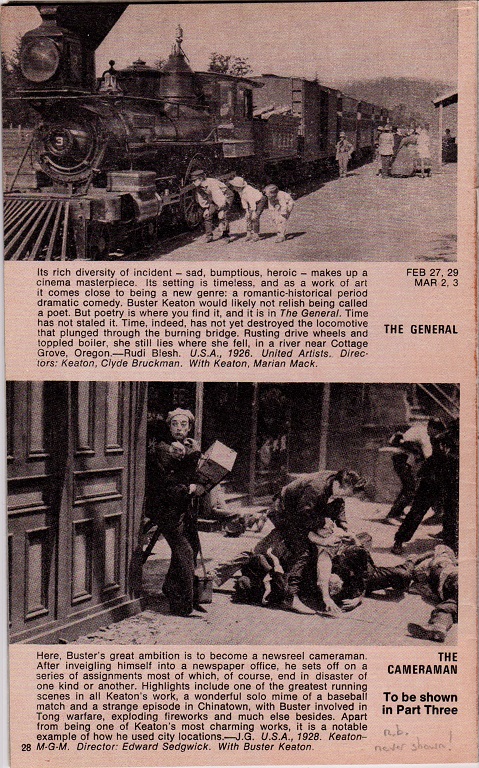

offered a series called “100 Clowns,” and among the

|

Images courtesy of Richard Warner. |

|

You think that’s interesting?

Well, remind yourself of what you discovered at the

Retrospective page:

The Cameraman was shown at the Cinémathèque Française

during the Buster retro in Feb/Mar 1962.

This was almost certainly the same print shown at the National Film Theatre in November 1959.

It was almost certainly part of the Cinémathèque Française collection.

It was almost certainly nitrate.

It is almost certainly still there, mislabeled, unindexed, miscatalogued, unknown, forgotten.

|

|

What else do we know?

We know that in 1964 MGM loaned Robert Youngson a fine-grain of The Cameraman so that he could pull excerpts for

The Big Parade of Comedy.

According to a NitrateVille post by Dick May on

30 May 2014,

MGM never retrieved this fine-grain from Youngson.

My best guess is that the fine-grain that Youngson used was the fine-grain that had been on deposit at the George Eastman House.

Bizarrely, any footage that Youngson included in The Big Parade of Comedy

was thereafter missing from the fine-grain.

It appears that Youngson physically cut the masters in his possession

to put together a new full-aperture (.723"×.964" approx.) action cutting copy.

The Big Parade of Comedy, by the way, was optically reduced to the Academy format (.630"×.864" approx.)

Since there needed to be an intermediate, why didn’t Youngson cut the intermediate rather than the master?

That makes no sense to me.

|

|

Thus it was that from 1964 through 1967, The Cameraman was a lost film.

It appears that nobody at MGM realized it was a lost film —

probably not until the BFI booked a print.

That’s when the MGM folks discovered that there was no print to ship over.

|

|

Richard Warner picks up that thread:

“In January to March 1968, [the BFI] mounted the

|

Image courtesy of Richard Warner. |

|

What happened to the material at George Eastman House?

My best guess is that MGM retrieved it in order to hand it all over to Youngson.

Was there ever material at MoMA? If so, what happened to it?

What happened to the foreign print shown at the NFT in 1959?

|

|

What else do we know?

We know that in January 1968 Raymond Rohauer made a huge splash

with his Buster Keaton Festival at the BFI’s National Film Theatre.

¿Time to jump onto the bandwagon, que no?

Let us return to that article in

Il Cinema Ritrovato:

“In 1968 Keaton films were in high demand and when MGM was unable to locate the studio fine grain

it made a 35mm

|

|

Well, we know for certain that the George Eastman House had 35mm material in 1951

and probably for at least a few years afterwards.

We know for certain that the George Eastman House made a 16mm print for Karl Malkames in 1951.

We know that MGM had a 35mm fine-grain at the end of 1957, which may well have been the one held at Eastman.

We know that MGM loaned a fine-grain to Bob Youngson in 1964.

Between 1951 and 1963, someone somehow got hold of this fine-grain, or a copy negative made from it, or a print,

late at night when no one was looking, and ran off a new copy, which was then copied further.

It was an inside job.

|

|

I would like to examine that 9.5mm print for

|

|

MGM’s Paris office acquired a 35mm Academy-format enlargement of the 9.5mm print no later than April 1968.

|

|

Seventeen weeks?

If this wire story were printed immediately, that would put the opening at about 27 May 1968.

The Boston Record American deleted the name of the wire service

and deleted the date of the story.

For all we know, this story could have been printed four months after it was first transmitted.

Oh. Wait. The glories of search engines.

It opened on Wednesday, 10 April 1968.

|

|

When this edition of The Cameraman was issued in the US, it had a piano track.

This must have been what was included in the French edition of 1968.

That piano track has been bothering me for decades.

Who played that piano?

Now, once upon a time, somewhere online, I bumped into this little

|

|

|

I wish I could remember where I found that.

I wish I the resolution were higher so that I could read the writing in that little cartoon.

The cartoon was probably a

|

|

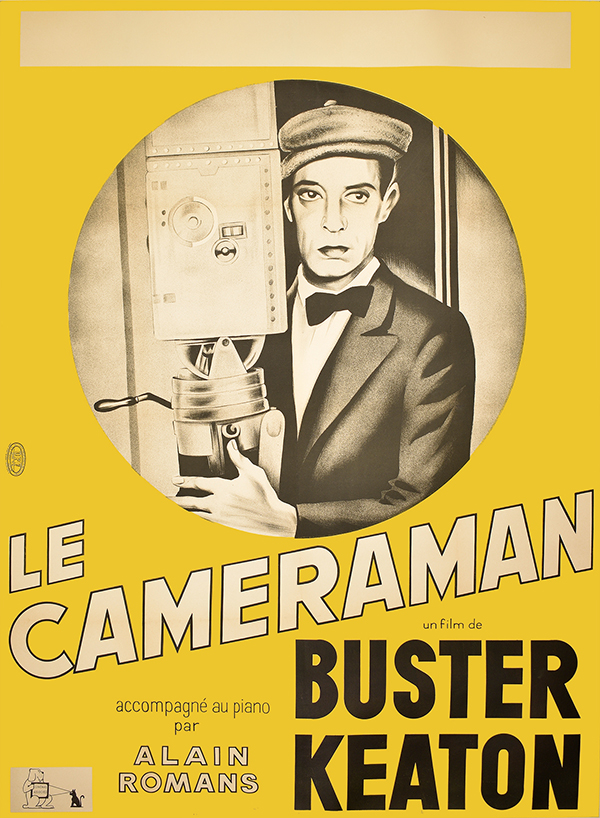

Was this poster made for a particular performance at which Alain Romans would perform live?

Or was this poster for a booking of a print with the piano track?

(Alain Romans, 13 January 1905 – 19 December 1988.)

|

|

How do we solve this mystery?

We solve it by learning Danish!

Or, actually, we just use Google Translator.

We discover that Ib Monty published a review of The Cameraman (Kanonfotografen)

in Kosmorama

vol. 89, 1968, pp. 96–97.

The final paragraph of that review is what we’re after:

“The Cameraman is still an exceptional film today.

Such a beautiful, graceful, clever and humane comedy is perhaps only found today in the films of Jacques Tati.

It is good that The Cameraman can now be seen again.

Image-wise, the present copy could be better.

Certain scenes are apparently missing from it as well.

In contrast, Alain Romans’s piano accompaniment is well-suited the film’s style.”

MYSTERY SOLVED!!!!! Oh how I love to solve mysteries!

|

|

$1,001.99.

Well, if I were rich....

We can see from this MGM poster that it was definitely not advertising a special live performance.

This was definitely a piano track by Alain Romans.

Oh well, at least I can now make out that

|

|

Interestingly, or uninterestingly, when The Cameraman was originally released in France, in 1928,

it had a different title:

|

|

As far as I know, MGM never made a poster for the new US edition, or a press sheet or any press materials whatsoever.

I certainly have never seen any.

You will notice that in the few ads below, cinemas had to invent their own graphics.

Most chose not to, but simply submitted typeset announcements without illustrations.

I suppose that the movie was the lowest of all low priorities,

which makes me wonder why MGM even bothered to offer the movie.

|

|

The next we hear about The Cameraman is when it was included in the seventh

New York Film Festival at Lincoln Center, 16 September through 2 October 1969.

The Festival’s published a

calendar in the newspapers, but made no mention of The Cameraman.

That was reserved only for the official calendar handed out to attendees.

John Dempsey, in his despondent summary in the Boston Sunday Herald Traveler,

12 October 1969, “Show Guide” p. 9,

explained that, in addition to the regular schedule, there were further movies shown by the Special Events Division

as publicity for the American Film Institute:

|

|

As we shall discover below, it was not MGM that rescued The Cameraman.

It was the government-operated American Film Institute that was responsible.

Was it the AFI that located that 9.5mm bootleg copy?

Was it the AFI that made a new 35mm dupe negative from it?

Was it MGM that paid for that service, or perhaps just reimbursed the costs?

|

|

According to Joan Kurilla,

“4,000 May Be as Available as a Pocket Novel: Unearthing Near-Forgotten Films,”

Center Daily Times (State College, Pennsylvania), Wednesday, 17 September 1969, sec. 2, p. 17,

it was our old friend David Shepard who was in charge of those restorations.

I wish I had known. I would have asked him about this. Oh well. Too late now.

|

|

As we saw above,

Raymond Rohauer gave his first full Buster Keaton Festival its US première

at the Surf in San Francisco, 25 September through 29 October 1969,

but we can see from the programming that this was not a 100% Rohauer endeavor.

Others were involved, movies other than Buster’s were included in the series,

and the closing week with The Cameraman was booked through MGM.

|

|

Later, the Beverly Hills branch of the American Film Institute

booked a 16mm retrospective of MGM movies from

10 December 1970 through 21 January 1971.

The previous screenings in DC were surely 35mm.

This time around, though, they were 16mm.

MGM had licensed these 16mm editions to

Films, Inc.,

which listed them in its first edition of the Rediscovering the American Cinema catalogue in 1970.

Among the films?

The Cameraman and Spite Marriage.

|

|

RecordCouncil, Films Incorporated Logo - 4K [35mm], posted on 19 November 2021. If YouTube ever disappears this, download it. |

|

MGM thought it worth its while to make The Cameraman and Spite Marriage available, in 35mm and 16mm,

but only for individual bookings and film clubs and specialty houses, not for general release.

|

|

The following list does not pretend to be complete,

but it is what I can easily find in online searches,

and it is surely representative.

|

|

Didn’t exactly set the world on fire, now, did it?

Well, I guess the film enjoyed its lengthy

|

|

Darn it! Darn it! Darn it!

I knew that the Rodey on the UNM campus occasionally presented silent movies,

but somehow I entirely missed this announcement.

Darn it!

|

|

I remember seeing this double feature at the

Sunshine in Albuquerque on a Saturday matinée, 17 March 1979.

912 seats. Only about 6 were filled.

Not so much as a chuckle.

A reason, of course, is that when a show is presented in a gigantic auditorium that is nearly empty,

people are not inclined to laugh, no matter how screamingly funny the material is.

Actually, in such a milieu, nothing is funny.

Another reason, of course, in regard to Spite Marriage, is simply that it is painfully bad.

My memory about the music on The Cameraman is a complete blank.

I was certain that I didn’t need to take notes because I was certain that I’d remember.

Wrong again.

Yet there can be no doubt that it was Alain Romans’s by-now-anonymous piano track.

Why his credit was deleted from the US release prints remains a mystery.

|

|

Richard Warner posted a message on “1928 in the public domain-- what can we expect?” NitrateVille,

on Friday, 5 January 2024:

|

|

In 1976, a BFI newsletter mentioned that Harris Films, UK agents for Films Incorporated, had 16mm prints

of The Cameraman and Spite Marriage for hire. Mention was made that Spite Marriage hadn’t been shown

in the UK since its original release and that The Cameraman hadn’t been seen here since the NFT 1959

screening in a print “heavily over-laden” with foreign titles. Spite Marriage was subsequently shown at the

1976 London Film Festival. A little later, the Electric Cinema of Notting Hill ran The Cameraman at their

|

|

By 1978, at the latest,

Enrique Bouchard of Buenos Aires

was offering Super 8 and 16mm copies of this exact edition of The Cameraman to collectors.

Apparently it was duped from a Films, Inc., release print,

which had been duped from MGM’s 35mm edition,

which had been duped from the 9.5mm print,

which had been duped from a dupe of the MGM/Eastman House material.

|

|

I have never seen any of Bouchard’s catalogues,

and so Richard Warner scanned this page of the 1978 catalogue for me.

|

|

On

21 June 1989,

MGM/UA published a poll.

It consisted of a long list of movies, including The Cameraman, and readers were to check off the 10 they most wanted.

|

|

On

15 July 1989, MGM/UA winnowed that list down to 25 titles, still including The Cameraman, and published a second poll.

|

|

See also the press release of

28 July 1989.

|

|

On

9 August 1989 came a third poll, with the list now reduced to 10 titles, still including The Cameraman.

|

|

Then, on

16 May 1990, MGM/UA announced that it was considering issuing The Cameraman and A Woman of Affairs.

|

|

Finally, MGM/UA issued the 9.5mm blowup of The Cameraman on VHS on

Wednesday, 20 February 1991, for the inflated price of $29.98. M302159.

It’s long out of print, but you can still find copies on eBay.

|

|

|

Going back to Dick May, he continued,

“when Turner first took over the MGM library the only thing we had

were film elements apparently optically enlarged from a narrow-gauge print found in France.

The quality, as expected, was quite poor.”

|

|

Then the unexpected happened.

Dick May related a story of what must have occurred sometime around April 1991.

|

|

One day I received a call from David Shepherd (well known in this forum),

telling me he had recently bought ‘a garage full of film’

from the estate of the late documentary maker Robert Youngson.

Among this film was a fine-grain positive of THE CAMERAMAN, missing the first 10-minute reel.

Apparently MGM had lent this to Youngson when he was making his compilation film MGM's BIG PARADE OF COMEDY,

and never retrieved it.

This was a safety acetate element, probably made from the original negative.

We made arrangements to get it from David, and made new 35mm film elements.

We still were stuck with the inferior reel 1.

|

|

MGM finally located the fine grain in 1991 —

when film historian and collector David Shepard found it in Robert Youngston’s

vast collection he had acquired —

though it was missing footage from single reels 1A, 2A, 3A and 4A.

The majority of footage removed from the fine grain was used

to create the documentary MGM’s Big Parade of Comedy.

|

|

So, anything included in The Big Parade of Comedy was gone from the fine-grain.

Several other bits and pieces were missing as well.

Apparently Bob Youngson had contemplated including them in his compilation but then decided against doing so.

For the 1991 restoration, some missing sequences had to be pulled from The Big Parade of Comedy.

Other missing shots were pulled from the enlargement of the 9.5mm dupe, and the beginning of Reel 3 was still a lost cause.

|

|

Karl Malkames’s grandson, Bruce Lawton, saw this preliminary restoration,

surely at the Film Forum 2 on Sunday, 30 June 1991,

and it was surely the following day that he alerted Dick May to his grandfather’s 16mm print,

which included the entirety of Reel 1 printed directly from the camera negative,

as well as a complete Reel 6.

Apparently Turner/MGM/UA no longer had a complete Reel 6 except in the poor enlargement of the 9.5mm dupe.

|

|

Bruce placed his phone call to Dick May just as work was beginning on a laserdisc release,

which was to have featured music suggested by

the original cue sheet, played by

Vince Giordano and His Nighthawks.

Alas, the rights to the period music proved to be prohibitive,

and so Alain Romans’s 1968 piano was retained for the laserdisc.

The deadline was too soon to allow for Reel 1 or 12 seconds in the middle of Reel 6 to be replaced,

and so those pieces remained in the 9.5mm dupe quality, as well as some other brief moments,

notably Yankee Stadium.

The editors decided to eliminate the glimpse of the Beverly Wilshire Hotel at the end of Reel 2,

apparently because it was too fragmentary.

You can hear an abrupt snip in the piano score at that moment.

|

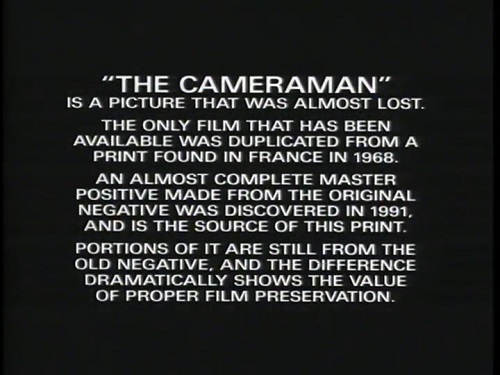

Opening disclaimer. |

|

And here’s the snip in the music. Ascoltate:

|

|

If the video does not display, download it. |

|

The upgrade was not abandoned at this stage, though,

for the new 35mm prints made just afterwards,

as well as the 2004 Turner/Warner DVD, included all the best footage known,

minus the last 13 seconds of Reel 2.

|

|

What do we learn from this?

MGM took no care of its assets on The Cameraman.

When the negative rotted, there seems to have been no urgency about locating backups.

Some of the backups may have gone up in smoke in various vault fires.

We do not know.

We do not know what happened to them.

When MGM loaned a fine-grain to Bob Youngson, it never bothered to retrieve its property from him.

When the AFI or MGM or somebody else found that 9.5mm bootleg in Paris, was there an effort to trace its origins?

Probably not.

When David Shepard dredged up Youngson’s collection, he could have kept it a secret.

Instead, he told Dick May, who was then left with a three-minute gap and a lousy Reel 1.

What attempts were made to locate the missing material?

Were there any attempts?

Then when Bruce Lawton approached with his grandfather’s copy,

again, nobody would have known had Bruce not made the effort.

It seems to me, and my perception could be wrong, that MGM and its successors were entirely passive, even lackadaisical.

Any material that fell into their laps, sure, fine, they would use it, but they would make no effort to find any missing pieces.

|

|

Then there is the Bob Monkhouse story, which you need to read.

Kevin Brownlow sent Patty Tobias an issue of Empire magazine #55, January 1994,

which included an interview with Bob Monkhouse.

We learn about this from Patty Tobias, “The Buster News,”

The Keaton Chronicle vol. 2 no. 1, Winter 1993/1994, p. 12:

|

|

But in 1977, in the dark days before the VCR, Monkhouse was arrested for

conspiracy to import feature films belonging to the major film companies.

Many of his movies were confiscated and it took two years before the case

against him was thrown out, with Monkhouse awarded costs. It is only when

recalling the episode that this supremely calm individual sounds unhappy —

bitter, even. “I had the missing scenes from Buster Keaton’s The Cameraman, one

of the greatest of all comedy films. I found a negative of it in Czechoslovakia,”

he mourns. “It got chucked in the police furnace, as did the only copy of the

British 1931 comedy Ghost Train.” Ironically, this is one of the “lost films” for

which the British Film Institute is now desperately searching, taking out ads in

various publications begging collectors to get in touch.

|

|

My interpretation of that was that Monkhouse had acquired the dupe negative he found in Czechoslovakia

and brought it back to his home in England.

My interpretation of that was that the police incinerated the actual dupe negative.

Totally wrong.

When he said that he had “the missing scenes”

I had interpreted that as meaning he had a complete copy that included the missing scenes.

I no longer interpret the story that way.

I bet that Monkhouse did not have a complete copy.

I bet he had only the missing scenes.

The story is a little more complicated, and, perhaps, a little more hopeful.

Keep reading.

|

|

Simon Brew,

“Bob Monkhouse, His Movie Collection, and the Bizarre Serious Crime Squad Case,”

Film Stories, 26 April 2021.

Monkhouse had found a dupe negative in Czechoslovakia, presumably at the Prague exchange,

and imported a 16mm print for his personal collection.

In all likelihood, he ordered only the end of Reel 2 and the beginning of Reel 3 to be printed to 16mm.

He offered it to the BFI, but the BFI had no interest.

In 1975, the police raided his home and confiscated his collection.

Though all charges were soon dropped, not all the films were returned.

Among the ones presumably dropped into the police department’s incinerator

was his 16mm material on The Cameraman.

Is there proof that it was incinerated?

Or is this just what someone said to Monkhouse,

or is this just an assumption?

Might it still be in a police file cabinet or evidence box?

|

|

That leaves open the question: WHAT HAPPENED TO THE DUPE NEGATIVE IN PRAGUE?

Remember, if there was a dupe negative in Prague,

then there were prints shipped to various cinemas throughout Eastern Europe.

Perhaps a few are still lying about, unnoticed, in forgotten cans after the labels fell off.

|

|

In addition to that, WHAT HAPPENED TO THE FOREIGN PRINT THAT WAS SHOWN AT THE NATIONAL FILM THEATRE IN NOVEMBER 1959?

We need to find it, or, at the very least, we need to learn its provenance.

|

|

There’s more.

There are rumors, probably true, of at least two original nitrate release prints

of The Cameraman being in the hands of private collectors, and these contain the

long-missing opening few minutes of the third reel. Allegedly, one of the

collectors is holding out for a price, and the other collector is too terrified of

lawsuits and property seizures to go public. My efforts to locate these two

collectors, even through middlemen to protect their anonymity, have been

thwarted.

|

|

The latest restoration was a collaboration among the Criterion Collection, the Cineteca di Bologna, and Warner Bros.

As

Il Cinema Ritrovato notes:

“FIAF archives and private collections around the world were combed to find the 291 feet of missing footage,

unfortunately without success.”

|

|

I think that there are several copies still around somewhere.

Anyone who holds out for a price will die disappointed.

That’s not the way archiving works.

I mean, my heavens, just look at the list of bookings above.

It was just a bunch of obscure showings in usually obscure venues usually for a single day.

This is not a billion-dollar property. Please.

The film is valuable, but as an objet d’ art, as a historical document;

it is of relatively little monetary value.

Not all value is monetary, though there are many people (I have met them)

who are incapable of comprehending that concept.

A collector who comes into possession of a missing film should ideally just turn it over,

but a collector who is adamant about earning some coin should just take a share of the distributor’s net.

That is absolutely the most a collector could ever hope to earn.

The discovery of lost films does not bring riches.

Don’t hold something for a ransom that nobody could afford and that nobody could ever earn back.

|

|

So, in sum, I think we have some leads.

How do we pursue them?

|